Abstract

Purpose

Globally, many children are exposed to violent discipline in multiple settings. Interventions to prevent violent discipline are therefore highly needed. In the present study, the feasibility of the intervention Interaction Competencies with Children – for Parents (ICC-P), an additional module of a school-based intervention for teachers, was tested. The intervention aims to prevent violent discipline by changing attitudes towards such method and fostering supportive adult-child interaction through non-violent interaction skills.

Methods

In total, 164 parents (Mage= 39.55, range = 24 70, 72.3% female) from four public secondary schools in Tanzania participated in a four-day training conducted by six trainers (Mage= 44.67, range = 40–47, 50% female). Using a One-Group Pre-Post design, we measured the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of the intervention qualitatively and quantitatively. Parents were assessed via self-administered questionnaires before and six weeks after the intervention. Trainers rated the implementation of every workshop session.

Results

Based on descriptive statistics and Classical Content Analysis, implementing trainers and participants rated ICC-P as feasible. Participants indicated a high need for such interventions and showed high acceptance. They were able to integrate core aspects of the intervention in their daily interactions with children. Using t-tests, ICC-P proved to be preliminarily effective; parents reported applying less violent discipline and holding more critical attitudes about such measures after the intervention.

Conclusion

ICC-P is feasible intervention that showed initial signs of effectiveness. We recommend combining the parents’ training module with the teachers’ module to prevent violence in multiple settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Violence against children, regardless of its form or reason, is a violation of children’s rights (United Nations, 1989). However, according to global research three out of four children, 1.7 billion children in total, reported experiencing interpersonal violence in the past year (KViC, 2017). Nine out of ten countries with the highest rates of violent discipline use against children are in Africa. Especially in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) children are at high risk of parental violent discipline with more than 90% prevalence in the past year (Gershoff, 2017; KViC, 2017). Parenting programs have the potential to reduce violent discipline. However, most of programs have been developed for and tested in high-income countries. This study aims to investigate the feasibility of an intervention for parents in low-income countries that can be integrated in a school-based approach to prevent children from violent discipline in multiple settings.

In the present study, we defined violent discipline as any emotional and physical violence perpetrated with the intention of causing pain to change or control the behavior of the child (Cuartas et al., 2019; UNICEF, 2010). Within this definition lies the dispute that violent disciplining is perceived as justified by the perpetrator. In Tanzania, the Law of Child Act, which was enacted in 2009, allows the use of violent discipline against children in any setting as a justifiable means of correction (Feinstein & Mwahombela, 2010; Gershoff, 2017). A study in a large nationwide sample of secondary students in Tanzania found that emotional violence had a past-year prevalence of 98% and physical violence of 94% based on child report. Further, 99% and 88% of the participating parents reported using emotional and physical violence, respectively, as forms of discipline (Nkuba et al., 2018b).

Consequences of Violent Discipline

Physical and emotional violence has been associated with a range of different negative effects for mental and physical health (Gershoff, 2002; Norman et al., 2012), such as increased externalizing problems (Hecker et al., 2014), antisocial behavior (Grogan-Kaylor, 2004) and aggression (Gershoff, 2002), as well as increased internalizing problems like depressive (Norman et al., 2012) and anxiety symptoms (Hecker et al., 2016). Further, violent discipline was correlated with lower levels of cognitive abilities and academic achievement (Kızıltepe et al., 2020; Masath et al., 2023b).

Despite the increasing awareness of the negative consequences, violence against children is still prevalent. This calls for effective preventative approaches to reduce the use of violent discipline against children. This is particularly urgent in countries where violent discipline is socially accepted. For example, in Tanzania violent discipline is generally seen as necessary and effective for controlling and correcting children’s behavior (Masath et al., 2022).

In the world report on violence and health, Krug et al. (2002) argued that it is necessary to focus on the perpetrators to understand the use of violent discipline and derive potential prevention strategies. They found that parents’ individual characteristics, such as age, education, income, substance use, or childhood experience of violence were related to the frequent use of violent discipline. Parents who experienced abuse or physical punishment during their childhood were more likely to use violent discipline measures on their children (Fernando & Ferrari, 2013; Rodriguez & Sutherland, 1999). In a study with parents of secondary school children in Tanzania, Nkuba et al. (2018b) identified parental stress as one important predictor of violent discipline of children. Parental stress can be caused by numerous multifaceted and overlapping factors. For example, studies argue that the more children live in a household, the more likely parents feel stressed with parenting responsibilities, resulting in greater risk of parental use of violent discipline (Dawes et al., 2005; Strauss et al., 2011). The gender of the parent may also influence the use of violent discipline. Research findings show that mothers are more likely to use corporal punishment than fathers, possibly related to the cultural expectations to serve as the primary caregiver (Dawes et al., 2005; Gershoff, 2002). Moreover, financial instability is related to parental stress (Slack, 2004). For example, parents with lower and unstable income were more likely to be burdened with family needs and thus become stressed (Dawes et al., 2005; Straus, 2010). As Tanzania is a low-income country, the majority of parents face low and unstable income streams (World Bank, 2021). Furthermore, research in SSA showed that teachers often applied violent discipline because they lacked knowledge about its negative consequences, alternative discipline strategies, and their effectiveness (Mweru, 2010; Nkuba et al., 2018b; Nkuba & Kyaruzi, 2015). Like teachers, parents in Tanzania may use violent discipline because they lack this information and knowledge.

Interventions for Parents

Parenting programs to prevent violent discipline have been shown to reduce child maltreatment and increase positive parenting interactions in meta-analytic research (Chen & Chan, 2016; Knerr et al., 2013; McCoy et al., 2020). One of the best evaluated parenting programs is Triple P (Sanders et al., 2002), which is based on behavioral social learning theory. The positive effects of this program include a reduction of problematic child behavior and parenting problems (Thomas & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2011). However, most research on parenting interventions have been conducted in high-income countries. Many parenting programs that have been developed for low- and middle-income countries have not been evaluated, for example the Better Parenting Training in Ethiopia, which targets parents and caregivers of vulnerable children. One of the few scientific evaluated programs designed for low- and middle income countries is the Parenting for lifelong health (PLH) program (Murray & Wessels, 2014). PLH showed effects for positive parenting strategies and reduced physical and emotional disciplining (Murray & Wessels, 2014; Ward et al., 2020). Another parenting program, which specifically addresses families in low- and middle-income countries is the Irie Homes Toolbox (Francis & Baker-Henningham, 2020). The intervention showed an increase in parents’ friendly interaction with their children and a decrease in the use of harsh punishment (Francis & Baker-Henningham, 2021). Both programs, PLH and the Irie Homes Toolbox focused on preventing violence disciplining by fostering supportive parenting skills in parents.

Social norms, attitudes, and personal beliefs are factors perpetuating the use of violent discipline (Straus, 2010). Therefore, we argue that it is also important to address these factors directly in societies where violence against children is socially accepted. This is the main aim of the preventative intervention, Interaction Competencies with Children (ICC). The feasibility and effectiveness of the intervention could already be shown for caregivers (ICC-C) in institutional care settings (Hecker et al., 2021, 2022; Hermenau et al., 2015) and with teachers (ICC-T) in schools (Ssenyonga et al., 2022; Nkuba et al., 2018a; Kaltenbach et al., 2018; Masath et al., 2023a). Violent discipline is a multi-contextual problem in Tanzania. Yet prevention programs seeking to address it in multiple settings are scarce. Therefore, we have developed an additional intervention module for preventing parental violence in the family context. Interaction Competencies with Children for Parents (ICC-P) aims at improving parent-child interaction, increasing positive parenting, and decreasing violent discipline. Examining the feasibility of this intervention module is an important first step to better understand the acceptability and implementation challenges of the intervention. In the future, ICC-P is meant to be combined with the teacher module of the ICC intervention (ICC-T). Ideally, children would interact with trained teachers at school and with trained parents at home. Applied together, they create a comprehensive, school-and-home-based preventative intervention program that aims to change and prevent violent behavior and foster consistent adult-child interactions at home and at school. In a previous study in California, collaborative school-home mental health interventions have shown great effects (Pfiffner et al., 2013).

Objectives

This pilot study aimed to test the feasibility of the newly developed ICC-P intervention module. It was set up in Tanzania, where violent discipline is still lawful in all settings and highly prevalent (Nkuba et al., 2018b; Sungwa et al., 2022). To test the feasibility of ICC-P, we conceptualized the relevant aspects of feasibility following Bowen et al. (2009). We hypothesized high feasibility ratings of the intervention, operationalized as demand, acceptability, integration, and implementation. In addition, this study aimed to test the preliminary effectiveness of the intervention in a One-Group Pre-Post design. We hypothesized a significant decrease in the use of violent discipline from pre- to post-intervention and a significant decrease in favorable attitudes towards violent discipline from pre- to post-intervention.

Methods

Setting, Design, and Sampling

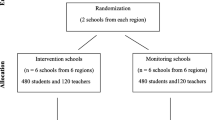

The study was conducted in two regions in Eastern Tanzania: Dar es Salaam and Pwani. In Tanzania, most secondary schools are public and require no school fee. Therefore, they reflect a sample representing a diverse variety of socio-economic backgrounds (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022). The regional and district educational offices approved the study and instructed the selected schools to participate in the study. To ensure the participation of schools, we organized a one-day workshop on positive teacher-student interactions for teachers as an incentive for the schools. In each region, two public secondary day schools were purposefully selected. The selected schools had limited resources, such as no electricity and a lack of teaching equipment. The school management sent invitation letters to 222 parents of students who were in their 8th year of study (age: 12 to 14). A total 180 (81.1%) of the invited parents participated in the training (see Fig. 1). One parent per family was invited to participate in the training. We decided to invite one parent per family mainly for logistical reasons, e.g. expected higher response rate. To include different family models, a parent in this study is defined as a primary caregiver who is emotionally and financially responsible for the child (Krug et al., 2002).

Flow chart of the study design and fluctuation of participants with three consecutive Saturdays of training and refresher day after six weeks. Notes. aThree participants were excluded due to having attended only one of the three training days. Another 33 participants dropped out due to unknown reasons. bIn total, 180 parents participated in the majority of training days (two of three days). cAn additional 13 participants joined on the second training day

Participants

A total of 164 parents (Mage= 39.55, SD = 8.8, range 24 to 70, 72.3% female, 77.1% married) participated in the training. Six trainers (Mage= 40.67, range 40–47, 50% female) implemented and evaluated the training.

Procedure

The intervention and data collection took place within the school facilities. Prior to the training, a researcher explained the aim of the study and procedures to the school management. On the first day of training, researchers and the head of school informed the parents about the purpose of the training. Voluntary participation and confidentiality were ensured, and open questions were answered before participants were asked to sign a consent form. The assessment was conducted prior to the intervention and six weeks after the intervention on the refresher day using self-administered questionnaires (see Fig. 1). Participants who were illiterate (ca. 50%) were assisted by research assistant in completing the surveys. The average time for completing the questionnaire was 25 min. During the intervention the trainers evaluated each session.

The intervention training was conducted on three consecutive Saturdays. The refresher training day took place six weeks after the last training day. Each training day took about 8.5 hours (for a more detailed training schedule please see Online Resource 1). The intervention training took place within a classroom of the selected school and was facilitated in Kiswahili language. Three trainer teams with two trainers each who had a background in educational and social psychology background with a master’s degree and had experience in delivering other modules of the ICC intervention carried out the training. The participation was free of charge, and participants received food, beverages, learning materials, and a transport compensation of US$4.35 on each training day. We obtained ethical approval from the ethics review board of Bielefeld University and research permits from the University of Dar es Salaam and all relevant authorities in Tanzania.

Intervention

The intervention module ICC-P was developed and adapted from previous ICC versions for teachers and caregivers (Kirika & Hecker, 2022) to make it suitable to the context of parents. The aim of ICCP is to promote positive parenting, improve parent-child interaction and to change attitudes and behaviors in relation to violent disciplining. ICC is based on attachment, behavioral, and social learning theories as well as on the parenting guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics (1999). The maltreatment prevention components are grounded in the work of Dreikurs (Dreikurs et al., 2004). A crucial step to foster participants’ openness to using non-violent strategies is to make participants critically reflect on their attitudes towards violent discipline (Kirika & Hecker, 2022). To challenge participants’ attitudes and beliefs, social norms and laws concerning violent disciplining are critically reflected in the first part of the intervention. Reflecting on their own childhood experiences of violence helps participants realize that violent discipline can affect emotions and behavior even many years later. This allows a reconsideration of internally integrated justifications for the use of violence against children and opens the participants up to non-violent alternatives. Knowledge and skills about effective non-violent parenting strategies are then discussed and practiced in the latter part of the intervention. The four core components of the intervention are parent-child interaction; maltreatment prevention, effective discipline strategies, and sustainability through repetition and implementation strategies (see Table 1). The implementation into daily family life is discussed and experiences are shared within the group. The training methods include inputs, plenary and small group discussions, self-reflection, and roleplays. Group and plenary discussions are important methods that allow participants to recognize that group dynamics can contribute to changing social norms and attitudes within the training group. To ensure sustainability, support, and exchange beyond the intervention, parents are encouraged to form support groups (face-to-face and virtual) and seek help from trainers if needed.

For the implementation, trainers followed the manual with guidelines and learning materials for each session. ICC-P was developed for low-resource settings. The required materials are kept to a minimum to make it implementable in settings with low resources (e.g. no electricity) and input is comprehensive and accessible for participants with low literacy levels. The intervention is flexible and can be tailored to the individual needs of the participants. More precisely, participants shape the intervention through their contributions.

Measures

Sociodemographic data were collected concerning parents’ age, gender, and marital status. Also, trainers’ demographic data concerning age and gender were assessed. The feasibility of the intervention was tested following the guidelines according to Bowen et al. (2009) and was operationalized with the following constructs: demand, acceptability, integration and implementation of an intervention. Data were collected with a mixed methods approach by collecting quantitative data and qualitative data through open-ended questions of participants and trainers.

Demand

The demand or the need for an intervention to prevent violence was determined by the occurrence of violent discipline and related constructs. Therefore, we estimated the demand prior to the intervention with the parent-child interaction, the prevalence of violent discipline and the attitudes towards its use. Purpose-built questions about the participant’s knowledge on parenting, general atmosphere in the family, interaction with children, and relationship with their partners gave insights on the parent-child interaction. The five items were measured on a five-point Likert scale (0 = Not satisfactory to 4 = Excellent). The two subscales physical violence and emotional violence of the Parent-Child Conflict Tactic Scale (CTSPC, Straus et al., 1998) assessed violent discipline by parents. The scale was adapted as reported in previous studies (Hecker et al., 2021; Nkuba et al., 2018a). The past-week rate of violent discipline was measured on a six-point Likert scale (0 = Never to 5 = More than ten times), consisting of 18 items with a sum score ranging from 0 to 90. Cronbach’s alpha for the 18-item past week violent discipline measure was 0.80. This suggests a high level of internal consistency among the items, indicating that they measure the same underlying construct reliably. Dichotomous answers were calculated to assess the lifetime prevalence of violent discipline.

To assess attitudes towards violent discipline we used an adapted version of the CTSPC that has been successfully implemented in previous studies (Nkuba et al., 2018a; Ssenyonga et al., 2022). The 18 items were assessed on a four-point Likert Scale (from 0 = never OK to 3 = always OK). The scale had a Cronbach’s Alpha of α = 0.80, which indicates a high level of internal consistency. This speaks for a good construct reliability. Additionally, nine items measured participants’ beliefs about corporal punishment on three points Likert scale (not true to certainly true). Cronbach’s Alpha was high with α = 0.84, which speaks for high construct reliability.

Acceptability

Prior to the training, acceptability was measured by purpose-built questions, which were already successfully implemented and slightly adapted from previous studies (Kaltenbach et al., 2018; Nkuba et al., 2018a; Ssenyonga et al., 2022). Trainees’ expectations regarding the workshop (e.g., motivational, relevance, interest) was measured on a nine-item three-point Likert scale (0 = Not true to 2 = Certainly true).

After training acceptability was measured by the participants’ perceived relevance of the workshop (e.g., understanding of the content, relevance of contents) on a five-item five-point Likert scale (0 = Not satisfactory to 4 = Excellent). Participants also evaluated the usefulness of the learned knowledge (e.g., many topics were new, topics were related to daily life with children) on a nine-item three-point Likert scale (0 = Not true to 2 = Certainly true).

Implementation

The implementation of each session of the training was evaluated by trainers after every second session (e.g.: time management, participant participation) on a seven-item five-point Likert Scale (0 = Not adequate to 4 = Excellent). In open-ended questions, trainers stated unforeseen challenges and difficulties that they encountered and offered ideas for improvement.

In the post-training evaluation, participants rated their satisfaction with the intervention (e.g., workshop in general, content of the workshop) on a four-item five-point Likert scale (0 = Not at all to 4 = Very much) and stated their ideas for improving the training in open-ended questions.

Integration

The integration of the training content was assessed at follow-up. Items were slightly adapted from previous studies (Kaltenbach et al., 2018; Nkuba et al., 2018a; Ssenyonga et al., 2022). Participants rated the transfer of knowledge into daily life on a six-item five-point Likert scale (e.g.: improvement of the relationship with children, changing understanding of children problems, 1 = Not at all to 5 = Very much). In open-ended questions they reported on methods that they thought are most realistic or unrealistic to use.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed using the Classical Content Analysis technique (Gondim & Bendassolli, 2014; Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007). In Classical Content Analysis, one researcher assigned themes and codes and discussed them with a second researcher and then they assigned descriptive titles (codes). One researcher counted the number of times each code was used and the second researcher cross-checked this. Multiple answers were possible. Quantitative data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics 25. To describe the concepts of feasibility, we used frequencies and means and standard deviations. In case of missing data in the feasibility measures, we used listwise deletion. To test the limited effectiveness of the intervention, paired t-tests of violent discipline, attitudes towards violent discipline and beliefs about violent discipline were conducted. We only considered 141 cases that participated in the pre- and the post-assessment. There were no missing values at pre-assessment in the outcome variables and very few (maximum of < 5% per case) at post-assessment. These missing values were missing completely at random. For the paired t-tests, we replaced missing values in the outcomes by using the last-observation-carried-forward method. The significance level was set at α = 0.05. Effect sizes considered small at d = 0.20, moderate effect at d = 0.50 and large at d = 0.80 (Cohen, 1988).

Results

Demand

In total, 99.4% (n = 166 out of N = 167) of the parents reported having used violent discipline to punish their children at some point in their life. The past-week prevalence of violent discipline of children was 92.2% (n = 154 out of N = 167). The most common form of violence was to threaten to spank or hit the child but not actually doing it, M = 2.2, SD = 2.0 (range: 0–5). Other frequently used practices were pinching the child, M = 1.8, SD = 1.9, and shouting, yelling, or screaming at the child, M = 1.9, SD = 1.8 (range 0–5). In total, 76.7% of the parents (n = 135 out of N = 176) thought it is OK to pinch the child. Most of the participants (84.1%, n = 149 out of N = 177) stated that it is OK to threaten to spank or hit but not actually doing it. More than half of the parents (n = 94 out of N = 174) stated that they believed violent discipline does not affect the parent-child relationship and 50% (n = 88 out of N = 176) believed that it is the only measure to make some children understand. Before the intervention, the satisfaction with family life was rated moderate across all scores (see Table 2). In total, 27.1% of the participants (n = 48 out of N = 177) rated their knowledge about parenting as very little.

Acceptability

Overall, participants had very positive expectations prior to the intervention (see Table 2). Participants thought that the planned workshop was highly needed for parents in Tanzania, M = 1.84, SD = 0.40 (range: 0–2) and they were looking forward to participating in the workshop, M = 1.76, SD = 0.51 (range 0–2). Although not all topics seemed to be new to everyone (M = 1.18, SD = 0.70, range 0–2).

After the training, the acceptability was also very high. It was evaluated as excellent and participants enjoyed the workshop very much, M = 1.99, SD = 0.17, (range 0–2) and were interested in the topics, M = 1.91, SD = 0.32, (range 0–2). Further, the relevance of the training was rated high with scores ranging from M = 3.48, SD = 0.72, (range 1–4) concerning the usefulness of the workshop for parents in Tanzania in general, to M = 2.99, SD = 1.05, (range: 0–4) concerning the understanding of the workshop. Most participants (n = 135 of N = 141), agreed that the training should be made widely available.

Implementation

The trainers’ average ratings of time management and parents’ comprehension were good, and ratings of parents’ participation, motivation, and overall feasibility were excellent (see Table 3). When asked about difficulties and unforeseen challenges, the trainers stated: many parents wanted to share experiences, but the time did not allow that; parents think it will be better if both parents will participate in the intervention training; training one parent became complex to implement. The most unforeseen challenges for trainers were that the self-reflection session lasted too long (n = 14, N = 40) and other time management issues (n = 13, N = 40). For more detailed results of the Classic Content Analysis please see Table OR2.1 in Online Resource 2.

From the participants’ perspective the overall satisfaction with implementation of the intervention was very high across all metrics (general, content, teaching methods, trainers) (see Table 2). As a suggestion for improvement most of the participants mentioned that they wished the training were more extensive (n = 64, N = 126) and that both parents should be included in the training (n = 14, N = 126). For more detailed results of the Classic Content Analysis see Table OR2.2 in Online Resource 2.

Integration

Six weeks after the training, the overall transfer into family life was reported to be high (see Table 2). Participants reported that the workshop helped them personally, M = 3.60, SD = 1.02, (range = 0–4), and that it changed the way they responded to their children’s behavior, M = 3.60, SD = 0.76, (range = 0–4). The improvement in the relationship with children was moderate, M = 1.96, SD = 1.81, (range = 0–4). Most participants (n = 131 out of N = 136) stated that they were applying positive parenting skills, e.g., to be close to the child, and respectful communication skills like talking to them in a friendly way. Secondly, they mentioned daily routines to mostly use in their daily family life (n = 65 out of N = 136). The major difficulty seemed to be prohibiting violent discipline measures (n = 56 out of N = 75), especially to set boundaries without using violent discipline like stop children from watching TV and playing games.

Preliminary Effectiveness

By comparing the CTSPC sum scores before the training and the scores six weeks after the last training day, we found a significant decrease of violent discipline at home with a large effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.94 (see Table 4). Participants reported to apply significantly less violent discipline measures at follow-up. From pre-assessment to the post-assessment, parents’ favorable attitudes towards violent disciplining declined significantly with a large effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.83 and participants reported significantly more critical beliefs about using violent discipline with a large effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.88 (see Table 4). Post-hoc analyses indicated a significant increase in participants’ knowledge of parenting skills with a large effect size of Cohen’s d = -0.91 (see Table 4).

Discussion

The many negative consequences of parental violent discipline for mental and physical well-being of millions of children worldwide require the establishment and utilization of effective prevention programs. In sub-Sahara Africa, the use of violent discipline against children is very common and education about non-violent parenting skills is lacking (Nkuba et al., 2018b; Nkuba & Kyaruzi, 2015). This study tested the feasibility of the intervention module ICC-P, which aims to improve the parent-child relationship and decrease parental use of violent discipline, with parents of adolescents (12 to 14 years old) in Tanzania. Overall, the results of this pilot study indicated a good feasibility of ICC-P. With more than 90% of participants reporting having used violent discipline against their children in the past week, the demand for such an intervention is pressing. The high prevalence is in accordance with previous studies in Tanzania (Nkuba et al., 2018b; Nkuba & Kyaruzi, 2015). In addition, participants reported to have favorable attitudes towards violent discipline as well as strong favorable beliefs about the usefulness of violent disciplines. Further, participants rated their knowledge about childcare as low.

Acceptance of the training and motivation to participate was high before and after the training and participants suggested that the training should be offered to more parents in Tanzania. All participants agreed that the topics of the workshop were relevant and practical for their daily life. Trainers rated the general implementation of the training as successful with a very high motivation on the part of the participants. Difficulties in the implementation mainly were related to time management issues. Parents reported a successful integration of aspects of the training in daily family life and a change in the way they respond to their children. Comparison of pre- and follow-up assessments should be regarded with care, due to the uncontrolled study design. Nonetheless, violent discipline as well as favorable attitudes and beliefs about it showed a significant decrease from pre- to post-assessment. In a post-hoc analysis, the knowledge in parenting increased significantly. Overall, ICC-P proved to be feasible and may have the potential to change attitudes and behaviors towards violent disciplining. This intervention, while promising, should be further evaluated in controlled study designs.

One of the core aspects of the intervention, tailoring it to the needs of participants, is a major reason for the high feasibility. Despite the diverse social backgrounds and education levels of the parents, the intervention was evaluated as relevant and understandable. Examples, repeated practice, and discussions are related to participants’ daily life experiences. The training thrives on active participation and consistently prompts participants to apply the content to their own lives. This promotes the personal relevance of the training. The intervention addresses individual aspects like individual parents’ function as role models, personal attitudes towards and own experiences of violent discipline, and the lack of knowledge and skills. Additionally, providing a safe and trusting atmosphere in which parents can freely discuss common challenges and worries drives openness and connectedness among the participants. Through reflection about laws and social norms, group discussions and practices, social norms that underlie violent disciplining are addressed and give participants the chance to reconsider their cultural and societal beliefs not only on an individual level but also in the parent community of the respective school. The findings of this study are in line with results from previous feasibility studies of ICC-T (Kaltenbach et al., 2018) and ICC-C (Hermenau et al., 2015), which found that participants started to question common societal beliefs and their own individual behaviors and had a better understanding of children’s behaviors and needs.

This approach differs from previous parenting programs, which focus mainly on changing violent behavior but not directly on participants’ willingness to change. The preliminary findings support the idea that focusing on attitudes that favour violent discipline may be of paramount importance in regions with high social acceptance of violent discipline.

Implications and Future Research

Many participants wished the training were more extensive. Looking at the dose-response, a more extensive training probably could lead to stronger effects (Hecker et al., 2021, 2022). This request must be countered by an increase of costs and additionally an increased risk of participant attrition. During the four days of workshop the fluctuation of participants was moderate, which mainly was caused by income activities and other family responsibilities. Extending the workshop might lead to higher fluctuations and dropouts.

Further, a frequent suggestion of participants was to include both parents in the intervention. In this study, we included only one parent to ensure openness among the participants and making parents more flexible in terms of family obligations. We agree that it could be beneficial to include the entire parenting environment of the child. In Kirika and Hecker (2022) we argue that including the entire team of teachers in the intervention is a crucial mechanism to change attitudes not only on an individual level but on the school level. The same is likely to apply for the family level as well. To ensure openness and considering other responsibilities of parents separated trainings or sessions for fathers and mothers might be helpful. In a previous study in orphanages in Tanzania, caregivers of the same institution took part in different interventions to ensure the continuous supervision of children. The intervention lead to a significant decrease in violent discipline (Hecker et al., 2021, 2022).

We believe that combining the intervention for parents and teacher to change the family as well as the school setting would likely lead to prevention of violence in multiple settings, which may promote children’s mental and physical well-being comprehensively. School-based interventions that involve both parents and teachers may open new possibilities to change attitudes towards violent discipline in multiple settings. To our knowledge, evidence-based school-based interventions combining trainings for parents and teachers are limited at this time. The promising results of ICC-P and ICC-T indicate a possible contribution to fill this gap. Future studies should evaluate the effects of applying this integrative approach. If these promising results can be replicated and the intervention proves to be effective, then the school-based approach has great potential for widespread dissemination. ICC-P could be established in schools via a train-the-trainer model that is integrated in the teacher training. Through trained master trainers from the teaching staff as focal persons at schools, it will then be possible to reach fellow teachers and parents.

Strengths and Limitations

Despite the challenges of limited resources and capacity, like illiteracy, fluctuations in participant attendance, and absence of electricity, ICC-P proved to be feasible. Although the results of the feasibility study are very promising, there are a few limitations to note. Due to the uncontrolled design no causal conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness, which should be investigated in controlled designs. Many items were purpose-built and adapted for this study. However, they have been successfully applied similarly in previous studies in Tanzania (Hermenau et al., 2015; Kaltenbach et al., 2018; Nkuba et al., 2018b). As we only included parents of children from public schools in two purposefully selected regions, the generalization of our results is limited. As most of the measures were based on self-reports, social desirability cannot be ruled out. Nevertheless, the high prevalence rates of the use of violent discipline reported in the pre-assessment speaks to the general openness of the participants. We tested ICC-P with parents of adolescents. However, the prevention of violence may also target parents of younger children as better outcomes may be expected in younger children (Nicholson et al., 2010).

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that the intervention module ICC-P was needed by the participating parents. It was accepted, well implemented and its implementation was feasible. Furthermore, it proved to have preliminary effectiveness; parents reported using less violent discipline after the intervention, potentially gained more critical attitudes and beliefs about violent discipline and increased their knowledge in parenting. Throughout the intervention, parents reported their willingness to change violent behavior. Participants stated that they were going to use the positive parenting skills that they had acquired from the intervention. ICC-P may influence a positive parent-child interaction and increase parental warmth. Overall, the results suggest that ICC-P was feasible to implement even in challenging, resource-limited circumstances. Further, they indicate that testing the effectiveness of ICC-P in a controlled study, ideally in combination with ICC-T as a school-based approach, is a promising way forward.

Data Availability

The corresponding author confirms that he had full access to all data and takes responsibility for the integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis. The study protocol, all assessment materials, and the datasets are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Bowen, D. J., Kreuter, M., Spring, B., Cofta-Woerpel, L., Linnan, L., Weiner, D., Bakken, S., Kaplan, C. P., Squiers, L., Fabrizio, C., & Fernandez, M. (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002

Chen, M., & Chan, K. L. (2016). Effects of parenting programs on child maltreatment prevention: A meta-analysis. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 17(1), 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014566718

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Cuartas, J., McCoy, D. C., Rey-Guerra, C., Britto, P. R., Beatriz, E., & Salhi, C. (2019). Early childhood exposure to non-violent discipline and physical and psychological aggression in low- and middle-income countries: National, regional, and global prevalence estimates. Child Abuse & Neglect, 92, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.021

Dawes, A., Zosa, K., Zuhayr, A., & Linda, R. (2005). Corporal punishment of children: A South African national survey. Save the Children International, 31. https://repository.hsrc.ac.za/bitstream/handle/20.500.11910/7142/3456.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 8 Dec 2023

Dreikurs, R., Cassel, P., & Ferguson, D., E (2004). Discipline without tears: How to reduce conflict and establish Cooperation in the Classroom. Wiley.

Feinstein, S., & Mwahombela, L. (2010). Corporal punishment in Tanzania’s schools. International Review of Education, 56(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9169-5

Fernando, C., & Ferrari, M. (2013). Overview of the volume. In C. Fernando, & M. Ferrari (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children of War (pp. 1–7). Springer Science + Business Media. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2013-16645-001&site=ehost-live. Accessed 8 Dec 2023

Francis, T., & Baker-Henningham, H. (2020). Design and implementation of the irie homes toolbox: A violence prevention, early childhood, parenting program. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 702.

Francis, T., & Baker-Henningham, H. (2021). The Irie homes toolbox: A cluster randomized controlled trial of an early childhood parenting program to prevent Violence against children in Jamaica. Children and Youth Services Review, 126, 106060.

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539.

Gershoff, E. T. (2017). School corporal punishment in global perspective: Prevalence, outcomes, and efforts at intervention. Psychology Health & Medicine, 22(sup1), 224–239.

Gondim, S. M. G., & Bendassolli, P. F. (2014). The Use of the qualitative content analysis in psychology: A critical review. Psicologia Em Estudo, 19(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-737220530002

Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2004). The effect of corporal punishment on antisocial behavior in children. Social Work Research, 28(3), 153–162.

Hecker, T., Hermenau, K., Isele, D., & Elbert, T. (2014). Corporal punishment and children’s externalizing problems: A cross-sectional study of Tanzanian primary school aged children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(5), 884–892.

Hecker, T., Hermenau, K., Salmen, C., Teicher, M., & Elbert, T. (2016). Harsh discipline relates to internalizing problems and cognitive functioning: Findings from a cross-sectional study with school children in Tanzania. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0828-3

Hecker, T., Mkinga, G., Hartmann, E., Nkuba, M., & Hermenau, K. (2022). Sustainability of effects and secondary long-term outcomes: One-year follow-up of a cluster-randomized controlled trial to prevent maltreatment in institutional care. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(5), e0000286. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000286

Hecker, T., Mkinga, G., Kirika, A., Nkuba, M., Preston, J., & Hermenau, K. (2021). Preventing maltreatment in institutional care: A cluster-randomized controlled trial in East Africa. Preventive Medicine Reports, 24, 101593.

Hermenau, K., Kaltenbach, E., Mkinga, G., & Hecker, T. (2015). Improving care quality and preventing maltreatment in institutional care–a feasibility study with caregivers. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 937.

Kaltenbach, E., Hermenau, K., Nkuba, M., Goessmann, K., & Hecker, T. (2018). Improving interaction competencies with children—A pilot feasibility study to reduce school corporal punishment. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(1), 35–53.

Kirika, A., & Hecker, T. (2022). Interaction competencies with children – development and theory of change of a preventative intervention for teachers in the context of socially accepted Violence. Verhaltenstherapie, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000525241

Kızıltepe, R., Irmak, T. Y., Eslek, D., & Hecker, T. (2020). Prevalence of Violence by teachers and its association to students’ emotional and behavioral problems and school performance: Findings from secondary school students and teachers in Turkey. Child Abuse and Neglect, 107, 104559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104559

Knerr, W., Gardner, F., & Cluver, L. (2013). Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Prevention Science, 14(4), 352–363.

Krug, E. G., Dhalberg, L. L., Mercy, J. A., Zwi, A. B., & Lozano, R. (2002). Child Abuse and neglect by parents and other caregivers. World Report on Violence and Health, 51(2), 57–81. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.9.1.93

KViC (2017). Ending Violence in Childhood:Overview,Global Report 2017. Lopez Design. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/ending-violence-childhood-global-report-2017/. Accessed 8 Dec 2023

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557–584. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557

Masath, F. B., Mattonet, K., Nkuba, M., Hermenau, K., & Hecker, T. (2023a). Reducing violent discipline by teachers: A matched cluster-randomized controlled trial in Tanzanian public primary schools. Prevention Science, 24, 999–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01550-0

Masath, F. B., Scharpf, F., Dumke, L., & Hecker, T. (2023b). Externalizing problems mediate the relation between teacher and peer Violence and lower school performance. Child Abuse & Neglect, 135, 105982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105982

Masath, F. B., Nkuba, M., & Hecker, T. (2022). Prevalence of and factors contributing to violent discipline in families and its association with violent discipline by teachers and peer Violence. Child Abuse Review. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2799

McCoy, A., Melendez-Torres, G. J., & Gardner, F. (2020). Parenting interventions to prevent Violence against children in low-and middle-income countries in East and Southeast Asia: A systematic review and multi-level meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 103, 104444.

Murray, M. T., & Wessels, I. M. (2014). Parenting for lifelong health: from South Africa to other low-and middle-income countries. In: Responsive parenting: a strategy to prevent violence. Bernard van Leer Foundation; 2014. p. 4

Mweru, M. (2010). Why are Kenyan teachers still using corporal punishment eight years after a ban on corporal punishment? Child Abuse Review, 19(4), 248–258.

National Bureau of Statistics (2022). Sensa Ya Watu na makazi ya mwaka 2022, Matokeo Ya Mwanzo. Unired Republic of Tanzania. https://www.nbs.go.tz/nbs/takwimu/Census2022/matokeomwanzooktoba2022.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec 2023

Nicholson, J. A., Berthelsen, D., Williams, K. E., & Abad, V. (2010). National study of an early parenting intervention: Implementation differences on parent and child outcomes parenting program implementation. Society for Prevention Research 2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-010-0181-6

Nkuba, M., Hermenau, K., Goessmann, K., & Hecker, T. (2018a). Reducing Violence by teachers using the preventative intervention Interaction competencies with children for teachers (ICC-T): A cluster randomized controlled trial at public secondary schools in Tanzania. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0201362.

Nkuba, M., Hermenau, K., & Hecker, T. (2018b). Violence and maltreatment in Tanzanian families—findings from a nationally representative sample of secondary school students and their parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 77, 110–120.

Nkuba, M., & Kyaruzi, E. (2015). Is it not now? School counselors’ training in Tanzania secondary schools. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(19), 160–170.

Norman, R. E., Byambaa, M., De, R., Butchart, A., Scott, J., & Vos, T. (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 9(11), e1001349. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349

Pfiffner, L. J., Villodas, M., Kaiser, N., Rooney, M., & McBurnett, K. (2013). Educational outcomes of a collaborative school–home behavioral intervention for ADHD. School Psychology Quarterly, 28(1), 25.

Rodriguez, C. M., & Sutherland, D. (1999). Predictors of parents’ physical disciplinary practices. Child Abuse and Neglect, 23(7), 651–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00043-5

Sanders, M. R., Turner, K. M., & Markie-Dadds, C. (2002). The development and dissemination of the Triple P—Positive parenting program: A multilevel, evidence-based system of parenting and family support. Prevention Science, 3(3), 173–189.

Slack, K. S. (2004). Understanding the risks of child neglect: An exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreatment, 9(4), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559504269193

Ssenyonga, J., Katharin, H., Mattonet, K., Nkuba, M., & Hecker, T. (2022). Reducing teachers’ use of Violence toward students: A cluster-randomized controlled trial in secondary schools in Southwestern Uganda. Children and Youth Services Review, 106521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106521

Straus, M. A. (2010). Prevalence, societal causes, and trends in corporate punishment by parents in World Perspective. Law and Contemporary Problems, 73, 1.

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Moore, D. W., & Runyan, D. (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(4), 249–270.

Strauss, K., Dapp, U., Anders, J., von Renteln-Kruse, W., & Schmidt, S. (2011). Range and specificity of war-related trauma to posttraumatic stress; depression and general health perception: Displaced former World War II children in late life. Journal of Affective Disorders, 128(3), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.009

Sungwa, R., Jackson, L., & Kahembe, J. (2022). Corporal punishment in Preschool and at home in Tanzania A Children’s rights Challenge. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1569-7

The American Academy of Pediatrics. (1999). In E. L. Schoor (Ed.), Caring for your school-age child: Ages 5 to 12. Bantam Books.

Thomas, R., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2011). Accumulating evidence for parent-child interaction therapy in the prevention of child maltreatment. Child Development, 82(1), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01548.x

UNICEF (2010). Child disciplinary practices at home. Evidence from a range of low-and middle-income countries. New York: UNICEF.

United Nations General Assembly. (1989). Convention on the rights of a child. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rightschild

Ward, C. L., Wessels, I. M., Lachman, J. M., Hutchings, J., Cluver, L. D., Kassanjee, R., Nhapi, R., Little, F., & Gardner, F. (2020). Parenting for lifelong health for Young children: A randomized controlled trial of a parenting program in South Africa to prevent harsh parenting and child conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(4), 503–512.

World Bank (2021). Economic Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/tanzania/overview#1. Accessed 8 Dec 2023

Acknowledgements

The study has been funded by Anke Hoeffler’s Humboldt-Professorship on Conflict Research and Development Policy sponsored by the Alexander-von-Humboldt Foundation.We like to thank all school counselors and heads of schools involved in this study for their efforts to connect with parents and support the study. We are very grateful to our research team, including Edna Kyaruzi, Godfrey Ernest Mushi, Beatha Simon Rwimo, Mary Ngowi, Doreen Manase, Meshack Kakulu, and Simeon Mgode.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mabula Nkuba, Eliud Kabelege, and Tobias Hecker contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Eliud Kabelege, Mabula Nkuba, Alina Schreiber, Katharina Hermenau, Anette Kirika, and Tobias Hecker. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Eliud Kabelege, Alina Schreiber, Anette Kirika and Tobias Hecker, and all authors critically reviewed previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Furthermore, the study followed the University of Bielefeld’s ethical guidelines.

Consent to Participate

The data collection process was carried out with the informed consent of all respondents.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Tobias Hecker, Mabula, and Katharin Hermenau were involved in the development of the intervention Interaction Competencies with Children – for Parents (ICC-P) tested in this study. There are no patents, products in development or marketed products associated with this research to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Resource 1:

Time schedule and content overview of ICC-P Workshop (DOCX 22.2 KB)

Online Resource 2:

Results of classical content analysis (DOCX 16.8 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kabelege, E., Kirika, A., Nkuba, M. et al. Improving Parent-Child Interaction and Reducing Parental Violent Discipline – a Multi-Informant Multi-Method Pilot Feasibility Study of a School-Based Intervention. J Fam Viol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00679-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00679-4