Abstract

Special education advocacy programs educate and empower individuals to become advocates for families of school-aged children with disabilities. Although special education advocacy programs are becoming more common across the globe, replication and wide scale implementation are needed to determine their credibility. The purpose of this study was to explore the replication of a special education advocacy program, the Volunteer Advoacy Project (VAP), to understand the motivation, process, and barriers to replication for community-based agencies. Participants included the staff of ten community-based agencies that submitted a proposal to replicate the VAP but did not receive funding to support the replication process. Applications, transcripts, emails, and field-notes were used to conduct qualitative data analysis and determine themes. Findings showed common motivations and a cyclical replication process. Common barriers related to limited: capacity and funding. Implications for research, policy, and practice are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Special education advocacy programs educate and empower individuals to become advocates for families of school-aged children with disabilities. Such programs are becoming increasingly common around the world (Ruparelia et al., 2016). For example, in Chile there is an advocacy program to educate individuals with intellectual disabilities, families of indivdiuals with disabilities, and professionals about self-advocacy and self-determination (Tenorio et al., 2021). In England, there is momentum for advocacy programs for parents of indivdiuals with disabilities and self-advocates to unite for systemic change in the disability field (Walmsley et al., 2017). Research suggests that advocacy programs improve parent (e.g., empowerment, knowledge, advocacy skills, Jamieson et al., 2017) and student outcomes (e.g., service access, Taylor et al., 2017). However, little research has examined the replication of advocacy programs (Goldman, 2020). Replication and wide-scale implementation are important undertakings in research. Without examining how programs are replicated, effective programs may be developed in isolation and limited to the site wherein they were conducted without being generalized to the population. By characterizing the replication process, barriers to replication can be identified and targeted to facilitate systematic replications. The purpose of this study was to explore the replication process of a special education advocacy program.

At the initial level of understanding the replication process, it is important to explore the motivation of practitioners to replicate a program. In the context of special education advocacy programs in the United States, there are federally-funded programs designed to educate and empower families of children with disabilities about their special education rights. Such agencies include Parent Training and Information Centers (PTIs, agencies staffed by parents of children with disabilities who offer free special education rights trainings for families) and Community Parent Resource Centers (CPRCs, agencies which target a marginalized population of families of children with disabilities to equip them with their special education rights) (Author, 2016). Community-based programs may also target educating and empowering families to increase their advocacy skills (Harry & Ocasio-Stoutenberg, 2021). Unfortunately, agencies may struggle to enable parents to advocate given limited funding, competing priorities, and overextended staff (Author, 2020). Thus, agencies may be interested in replicating a special education advocacy program to expand their capacity to meet the needs of families. By understanding the motivation of agencies to replicate an advocacy program, we can better discern the goodness-of-fit between the program and the motivation of the agency.

After determining the motivation of the agency to replicate the program, it is important to characterize the replication process. Given the dearth of research about replication of advocacy programs, there is little known about the replication process. However, when examining the broader research about the replication process, it seems that one aspect of the replication process may be adapting the intervention to meet the needs of the new population and then testing the adapted intervention with the new population (Valdez et al., 2013). Given that each population is different, it is expected that some adaptations of an intervention will need to occur before it can be applied to a new population (Morrison et al., 2009). By better understanding the replication process, we can determine where in the process agencies struggled with replication and target that aspect of the replication process for intervention.

Finally, it is important to identify barriers to replicating an intervention. Beyond questions of effectiveness, we need to understand whether there are barriers related to the feasibility of implementing the intervention (McLaughlin et al., 2012). Without being feasible, the intervention cannot be replicated. Feasibility may include whether an agency has sufficient resources, funding, and trained staff to conduct the intervention. By identifying the barriers to replication, these barriers can be targeted for intervention so they can be mitigated.

For this study, a conceptual replication framework (Coyne et al., 2016) was used to explore the replication process. In a sample of ten agencies, we collected data to explore the replication process of The Volunteer Advocacy Project (VAP), a special education advocacy program. In 2018, the VAP was developed to address a need for special education advocates in one state. The mission of the VAP is to develop non-adversarial advocates who can provide instrumental and affective support to parents of children with disabilities in receiving educational services (Author, 2013). A total of 36 h of training is provided in the form of didactic instruction, discussion, role playing, and case studies based on assigned readings. In the United States, the VAP is the only special education advocacy program that has evidence of its efficacy (e.g., Author, 2019) and feasibility (Author, 2016). By understanding the motivation, process, and barriers to replication, we can identify ways to replicate the VAP across different settings. Replication research is critical to establishing the scientific credibility of an intervention (Ioannidis, 2012); thus, this study fills an important gap in the literature. Our research questions were: (1) Why do community-based agencies want to replicate the VAP?; (2) What does the replication process look like for community-based agencies?; and (3) What are the barriers to replication?

Method

Participants

The staff of ten community-based agencies participated in this study. To be included in this study, each agency needed to submit a proposal for funding and indicate an interest in receiving support to replicate the VAP, even though not selected to receive funding for replication. The ten agencies that participated were community-based disability agencies, including CPRCs and PTIs. The agencies were located across all regions of the U.S. The agencies varied in size, as indicated by the number of families they reported serving annually (range 50 − 13,500). Seven agencies reported providing some type of advocacy as part of their existing services. See Table 1 for information regarding each agency.

Recruitment

The Family Support Research and Training Center (FSRTC) held a request for proposals for agencies interested in replicating the VAP. Information was disseminated through the PTI and CPRC network. Nineteen agencies applied for the funding. A team of experts in family support interventions reviewed the proposals. Of the 16 agencies that applied but did not receive funding, 10 agencies expressed continued interest in receiving non-financial support to replicate the VAP.

Procedures

Institutional Review Board approval was received for this study. All agency representatives provided informed consent to participate in this study. Agencies were given electronic access to the VAP curriculum along with its application, research measures, and answer keys.

Each agency was given the option of attending three, live one-hour webinars about implementing the VAP. The webinars were created by the VAP developer (the first author). The first webinar focused on the logistical aspects of implementing the VAP. The agenda included: (a) overview of the VAP, (b) VAP components, (c) scheduling, (d) recruitment, (e) speakers, (f) materials, and (g) distance sites. The second webinar focused on the content of the VAP. The agenda included: (a) broad overview of content, (b) example of content (e.g., Powerpoints and case study examples), (c) changes to reflect state specifics, (d) facilitator guidelines, and (e) fidelity. The third webinar focused on conducting research with the VAP. The agenda included: (a) formative evaluation, (b) summative evaluation, (c) research for VAP coordinators, (d) research for VAP participants, and (e) next steps. Throughout each webinar, participants had opportunities to ask questions verbally or in the chat. The webinars were scheduled based on the availability of the participants. Each webinar was offered twice, giving participants two opportunities to attend the webinar. Each webinar was also recorded; agencies could watch the recording at any time. No data were taken about the number of times an agency watched the recording.

Each agency was also given the option for individualized technical assistance. Technical assistance was defined as individual meetings to discuss specific logistics and questions related to the adaptation process for an individual agency. Some examples of topics discussed during technical assistance include: questions related to logistics such as the timeline for implementation and discussion of decisions related to adapting course materials or terminology. All technical assistance was provided over the phone by the first author and scheduled at the date/time preferred by the participant. Technical assistance was available to participants as many times as requested. Meeting length averaged 30 min, ranging from 20 min to 1.5 h. Throughout the replication process, agencies also emailed the first author with questions that were answered in an email response.

Data Sources

The following six sources of data were collected to answer our research questions.

Applications

Each agency completed an electronic application which included nine open and close-ended questions. Sample questions included: “What services and supports does your organization provide?” and “Describe your plans for implementing the VAP.” There was no character count for responses.

Webinar Transcripts

Each of the webinars were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Questions asked during the webinars were documented and included in data analysis. Additionally, attendance data, collected during live webinars, were included as a data source.

Technical Assistance Meetings

Each technical assistance meeting was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. For each meeting, three questions were asked by the first author: “What questions do you have?”; “How are you feeling about implementing the VAP?”; and “What can we do to help?”. The total number of technical assistance meetings for each agency was summed.

Field Notes

The first author recorded detailed notes during and after each webinar and technical assistance meeting. The notes recorded the content as well as the tone of the participants.

Emails

All email correspondence between the first author and participants related to the replication process were saved and included as a source of data. The total number of emails was summed for each agency.

Follow-up Interview

Each agency that began to implement the VAP for their constituents participated in a semi-structured interview with the second author, who was not directly involved in the replication process. Interview questions mirrored those used in follow-up interviews with agencies that received funding to replicate the VAP (Authors, 2023). The interview protocol included grand-tour questions (e.g., “Tell me about how you implemented the VAP at your organization- what did it look like? Walk me through the process.”) as well as an outline to address key topics aligned with our research questions (e.g., resources, process). The interview was transcribed and included as a source for data analysis. Each interview lasted approximately 45 min.

Data Analysis

Coding

After familiarizing ourselves with all of the data by reading and re-reading transcripts and written materials and listening to audio recordings (Tesch, 1990), several steps were followed to analyze the data in adherence to collaborative qualitative analysis (Richards & Hemphill, 2018). First, open and axial coding were used to identify patterns related to the replication process as well as barriers and facilitators to replication. We independently coded each data source (e.g., application, field note, transcript) line-by-line, utilizing a constant comparative method (Krueger & Casey, 2009; Savin-Bader & Major, 2013). Then, we met to review and compare codes, discussing differences and agreements. This iterative process continued until we came to a consensus on the main themes and sub-themes that emerged from the data related to the replication process.

Trustworthiness

To promote trustworthiness, transcripts were triangulated with agency applications and field notes collected during the technical assistance meetings and webinars. Researcher triangulation was also performed to control for analysis drift. For example, we sought out areas of disagreement and had discussions until agreement was reached during data analysis.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

There were no potential conflicts of interest in this study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study received approval from the University Institutional Review Board to conduct research with human subjects. Each participant provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Findings

Preliminary Results

All participants completed the application to replicate the VAP and participated in some aspect of the webinars and/or technical assistance. See Table 2. Altogether, two agencies began to replicate the VAP within the timeframe for this study. Specifically, one of the two agencies replicated the entire VAP while the other agency had to stop delivering the VAP due to staff personal reasons. Other agencies stopped the replication process at earlier points. For example, four agencies attended 100% of the live webinars. Of the agencies that completed all webinars, three agencies requested and attended at least two technical assistance meetings. In total, seven agencies attended at least one technical assistance meeting. On average, agencies attended 1.3 (range 0–4) technical assistance meetings and had 3.4 email exchanges (range 0–10) with the VAP developer. The two agencies that began to replicate the VAP had the highest number of technical assistance calls and email exchanges.

Motivation for Replication

There were six main reasons for wanting to replicate the VAP. Notably, three reasons were the most common, cited by at least four agencies each. These reasons included wanting to: build capacity; better support underserved populations; and increase the availability of advocates to attend IEP meetings. First, agencies wanted to build capacity to support more families of children with disabilities and “fill a need.” A staff member from a southern PTI explained:

As an organization, I know we will never have the capacity to provide the type of support all parents need. Therefore, the key is to create a program that utilizes volunteers to offer some of this support. This will also help us grow new advocates, which is desperately needed.

Similarly, a staff member from a small, community-based agency shared on their application that, “The VAP program will allow us the opportunity to expand our educational advocacy…and to properly train volunteers where we have the biggest need.” Altogether, agencies focused broadly on supporting more families. As explained by a northwestern PTI, “This [the VAP] will be one support in our tool-box of supports and services to families.”

Second, many agencies noted plans to utilize the VAP replication to expand existing advocacy services specifically to better support underserved local populations. Participating staff from a western PTI explained on their application that, “Our goal is to increase the number of skilled, equipped parents who can deliver culturally-competent, community-based peer-to-peer support for families in targeted (historically underserved or marginalized) communities.” Specifically, nine agencies planned to target low-income families, seven agencies planned to target Latino families, and six agencies planned to target rural families. In addition, three agencies planned to target specific racial minority families. For example, a southern CPRC planned to target families who were dually involved with different service delivery systems including juvenile justice, mental health and foster care. Another agency, an advocacy organization, planned to focus on wards of the state and their families. Finally, a small CPRC in the northeast planned to focus on three subpopulations: homeless families, grandparents raising grandchildren, and families impacted by domestic violence.

The third most commonly cited reason for wanting to replicate the VAP was to increase the availability of advocates who could attend IEP meetings with families. A staff member from a southern PTI highlighted the importance of having advocates attend meetings with families because: “A frequent request from parents is to have a support person at an IEP meeting with them…given our catchment area of the entire state, that is not always possible.” A staff member from a southern community-based agency reported that, while she often attended IEP meetings with families herself, she didn’t “feel 100% sure that she could do it”. She was looking to the VAP to help educate herself about special education as well as to develop advocates to increase the cadre of educated individuals to attend IEP meetings with families.

To a lesser extent, reasons for wanting to replicate the VAP included: training agency staff; expanding special education legal representation; and improving transition supports. Two agencies reported wanting to replicate the VAP so they could provide training to their own staff. One, a midwestern community-based agency, specifically wanted to use the VAP for staff training that would align with the mission of their current advocacy program in the schools. Another agency more broadly wanted to use the VAP to train staff to help families. A different agency wanted to replicate the VAP “…to expand the type of direct legal services provided to residents…into the area of special education law with an emphasis on advocacy.” Finally, a midwestern community-based agency stated “the intent of the Volunteer Advocacy Project fills an important gap in our programming…” to specifically improve supports to transition-aged youth with disabilities and their families.

Replication Cycle

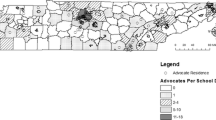

The replication process reflected a four-part, multi-directional cycle. The cycle included: recognizing a need; acknowledging existing supports; identifying additional needed supports to replicate the VAP; and determining needed adaptations. See Fig. 1. Throughout the cycle, agencies benefited from suggestions provided during technical assistance meetings related to adaptations and external supports.

First, agencies reported recognizing a need for the VAP to serve their constituencies. This step was often reported in the application and the first technical assistance meeting. A southern community-based organization reported, “This is a much needed project for our state. The area is rural and there are limited resources available. The need is so great and having more people to assist me would be great.” Similarly, a PTI in the south indicated on their application that, “We are ready to go [replicate the VAP] and believe the training and infrastructure provided will help us launch a robust program.” A PTI in the northwest indicated on their application that they were already providing a wide range of supports and informational resources for families, with the exception of advocacy support in the special education process.

In the second part of the cycle (i.e., acknowledging existing supports), across the applications and technical assistance meetings, agencies identified internal resources available for replicating the VAP that would enable them to be “ready to go.” Such resources included their infrastructure (e.g., software to monitor advocacy activities) and their extant special education knowledge (e.g., staff people were parents of children with disabilities who were familiar with special education). During an interview, a staff member responsible for VAP implementation at the advocacy organization explained how her background helped increase the likelihood of replicating the VAP: “I have a background as a teacher and one of the other directors is a trainer because he has been training for 23 years.” Participants also highlighted existing supportive partnerships with other advocacy and educational organizations in the community. On their application, a large northwestern PTI described that “These organizations have trusted ‘boots on the ground’ in immigrant, minority, underserved, and marginalized communities, and they want to help us reach and support families who face barriers to participating in their child’s educational and future planning.”

For the third part of the cycle, agencies reported needing additional supports. Although, on their applications, agencies identified supplemental funding and complimentary programs that would help sustain VAP implementation, many agencies were concerned about funding the VAP. In their second technical assistance meeting, a staff member from a large community-based agency shared, “We’ve got our presence in our metro area, because we have funding to support that. But how do we get it across 93 counties?… how do we support it?” Two agencies also reflected on whether they had the expertise needed to answer trainees’ questions about technical content. In a technical assistance meeting, a staff member of a small, community-based agency shard her concern that “I don’t feel 100% sure that I have confidence to do it.” The staff member then asked for supplementary materials (i.e., answer key for the VAP case studies) because “That was a concern of mine, just in case I didn’t know the right answer to something.” The participants discussed building on partnerships with other disability organizations to serve as “resident experts” in special education law. During an interview, the staff member who began to implement the VAP at a CPRC in the northeast reported that, “I was the trainer. However, I was not really qualified to be the trainer, even though I was qualified through the experiences of working with families.” She expanded that “If we were doing things again, I would bring in some of the experts.”

Finally, adaptations to the VAP were often determined during technical assistance meetings to “use it in our own way.” Adaptations included: mode of delivery (e.g., remote vs. in-person; synchronous vs. asynchronous), scheduling (e.g., daytime vs. evening, fall vs. spring), updated content (e.g., state law, local context [charter schools]), cost (i.e., free vs. paid), language (i.e., translated or English only), and participant requirements (e.g., prior knowledge of basic rights). During technical assistance, the first author would discuss whether adaptations would jeopardize the integrity of the original program. For example, the first author would compare the suggested adaptations to see if they conflicted with the fidelity manual for the VAP. Also, the first author would consider whether the suggested adaptations had a research base. For example, since the VAP has been offered and tested in multiple modalities (e.g., in-person, telehealth, Author et al., 2016), adapting the mode of delivery was not deemed to jeopardize the program. Along with the benefits of this flexibility, the participants discussed potential trade-offs of different adaptations. For example, in a technical assistance meeting, a staff member from a PTI in a western state brainstormed with the first author because there were “so many different things we can do. Do we do Saturdays? Do we do nights? So we have to think about how we are going to implement it.” When the first author suggested recording some sessions to allow people to watch from home, the staff member responded, “Are you saying this program can be a webinar? Because they are gonna be with people, I would be nervous about them having a webinar without them asking me questions and stuff like that.” After further clarification and discussion, they agreed, “That would be good. If there was something that was archived. Then if they miss it they can still look at it later… so it’s like all these different trade-offs.” However, not all agencies adapted the VAP; the northeast CPRC that began to implement the VAP used the original VAP materials without adaptations. The staff member who conducted the VAP noted that “Whatever she [first author] had is the way it was set up… I was trying to stick to that.”

After completion of the VAP, the implementer at the midwestern advocacy organization made additional adaptations to materials based on their experience and participant feedback. They “lifted information” from the original VAP materials and started adapting them for their future participants with additional prior knowledge so “we didn’t have to do so much build-up into it [content].”

Future Plans

Despite varied degrees of completion of the VAP replication process, half (n = 5) of the agencies indicated plans to conduct the VAP in the future. See Table 2. Of all 10 agencies, only one indicated definite plans not to use the VAP in the future. Specifically, at a small community-based agency with limited staff, the staff member indicated she had “too much to do with everything else I have going on.” Thus, she could not implement the VAP. Notably, a staff member from the CPRC that began implementing, but did not complete, the VAP, indicated that she would consider conducting the VAP again with more staff. She also added that she would make adaptations to the VAP stating, “I know what I would do differently.” She shared, “I would allocate it to somebody who has a child who’s going through school, who has a great deal of interest in it… for those little pieces that need to be added and personalized.” After replicating the VAP, the staff member from the advocacy organization shared her plan to, “build our next VAP training as community outreach events.” She also stated that, “From the agency perspective, we will continue to roll this out even beyond–as we grow our team into even more regions of the state we are going to mandate they take the training as well.”

Barriers to Replication

The most commonly reported barrier to replication was a lack of staff capacity at the agency. During technical assistance meetings, seven agencies reported that a lack of staff time made it difficult to replicate the VAP. In an email, a Western PTI reported that, “We are in the middle of planning and implementing a new funded project that I have to make sure is up and running before we do the VAP.” Thus, competing priorities and limited capacity served as barriers to completing the replication process. To some extent (and related to the lack of capacity), the lack of funding also impeded replication; three agencies reported that the lack of funding made it difficult to replicate the VAP. Because funding was not available to pay staff to work specifically on the VAP, other programs and competing priorities (such as the one cited above) took precedence.

Three agencies mentioned concerns about recruiting enough trainees to conduct the VAP. Staff from one agency shared that, “I put it out there to a few people that I thought would be interested in it. Some were, some weren’t… they say, ‘You know, I just don’t have that availability’.” Staff cited issues related to the time commitment required for completing the VAP and advocating for others. The northeastern CPRC that began to implement the VAP successfully recruited participants but had issues with attrition after the first few sessions. The staff member noted that, “It was short lived… I had the feeling that once they [the trainees] gathered the information that they wanted that was specific to their situation they didn’t feel they needed to come anymore,” adding that “it was disappointing when it didn’t go any further.”

Other barriers were less common and related to specific agencies. An eastern CPRC staff person was concerned about advocates being prosecuted under unauthorized practice of law. The staff member shared, “In our state, we do not say that we are advocates as the expectation is that we have legal training and we are very careful about unauthorized practice of law.” A staff member from a southern community-based agency indicated a lack of sufficient interest from partnering agencies. The staff member explained:

I still totally love the idea [of the VAP] but I’m not having any luck getting enough other partners on board to join me in doing it. I just work with a lot of tiny non-profits who are so stretched. I’m still hopeful it could come together one day, though.”

Similarly, an agency in the Midwest reported insufficient special education knowledge among staff to be able to replicate the VAP, sharing, “I don’t feel 100% sure that I can have the confidence to do it. I am not as fluent in special education law.” Notably, this was a community-based organization (not a federally-funded PTI or CPRC).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the motivation, process, and barriers for agencies replicating a special education advocacy program, the VAP. To understand the credibility of the VAP (Ioannidis, 2012), the ability for the VAP to be replicated by other agencies must be established. We had three main findings. First, most agencies were motivated to conduct the VAP to support more families of children with disabilities and build their capacity, especially in relation to IEP meetings. The desire for an advocate to attend an IEP meeting is a common need among families of individuals with disabilities in the United States (Goldman, 2020). Participants across all agencies also wanted to expand advocacy services to support specific underserved populations. The combined motivation to meet an expressed need in the disability community in an equitable way aligns with the larger literature which shows that marginalized families of individuals with disabilities who experience unique, systemic barriers especially benefit from advocacy programs (Author, under review).

Interestingly, while the motivation was to increase capacity, one of the major barriers to replication was the lack of capacity and resources of the agency. This finding underscores the tradeoff of needing to invest time, staff, and resources into something before there can be a payoff—this includes, time, staff, and resources that many agencies reported lacking. This finding has several implications. On a practical level, this finding suggests that start-up funding may help agencies replicate the VAP. Also, this finding suggests that agencies should be better informed about the cost (in terms of fiscal, resources, staff time, and training) to replicate the VAP. Specifically, such information should be available before the agency begins the replication process.

Second, the replication process involved a four-part, multi-directional cycle. Although the agencies provided ways to sustain the VAP and listed their available resources in their application, they needed to revisit their resources and related needs throughout the replication process. Notably, during the technical assistance meetings, agencies were able to identify creative solutions to adapt the VAP. For example, several organizations discussed identifying didactic content that could be pre-recorded and presented asynchronously to reduce staff and trainee time. This may be especially useful for rural families who might not otherwise be able to travel long distances to access this important information (Epley et al., 2011). However, tradeoffs for each adaptation should be considered. For example, trainees may be more likely to agree to participate in a remote training, but may be less engaged and have fewer opportunities to build community with a cohort of other parents. Notably, the literature is mixed regarding the efficacy of advocacy programs delivered virtually with some research suggesting no significant differences between in-person and virtual instruction (Author, 2016) and some research suggesting worse outcomes with virtual (versus in-person) instruction (Taylor et al., 2017). This balance of flexibility and efficacy should be examined in future research.

Third, agencies planning to replicate the VAP need staff with special education knowledge. Previous research about the replication of the VAP has suggested that organizations implementing the program should have staff with high levels of knowledge about special education law to effectively utilize the program (Author, 2022). This study provides additional support for that recommendation. Organizations that specialized in other areas (e.g., transition and adult services) experienced their lack of expertise in school-age services as a barrier.

This study also extends the literature by suggesting that, smaller organizations, compared to larger organizations with federal funding (e.g., PTIs, CPRCs) had limited capacity to adapt and implement the VAP using their existing infrastructure and resources. The only agency that indicated they did not plan to continue the VAP replication was a small, community-based agency that did not provide advocacy services at the time when they applied. It may be more impactful to focus on agencies with well-established infrastructure and expertise while also expanding the pool of eligible organizations beyond PTIs and CPRCs. In this study, the sole agency that successfully replicated the full VAP was an advocacy organization. Focused on protecting the rights of persons with disabilities, this is not an agency with a primary mission of supporting families of children with disabilities. Regardless, our findings show that this agency was able to successfully adapt and implement the VAP using available resources to meet its needs.

Limitations of the Current Study

While an important launching point, this study had several limitations. First, no observations of the VAP replication occurred; thus, this study is based on self-report. Observations would help to understand the replication process of the VAP among the agencies that replicated it to different degrees. Second, no data were collected with the participants in the VAP replications; thus, this study cannot speak the efficacy of the VAP when replicated by agencies without funding. Third, some agencies that applied to replicate the VAP but did not receive funding declined to participate in the study and receive free technical assistance. It is unknown why they declined to participate. Fourth, agency size and characteristics of agency staff (e.g., educational background, years of working at the agency) may impact the ability of an agency to replicate the VAP. While such data were unavailable in this dataset, future research should explore whether how agency and staff characteristics may relae to the ability to replicate a program.

Directions for Future Research

Future research is needed to examine not only the initial steps of preparing for replication but also the outcomes of actual implementation of the VAP by community organizations with and without funding. While research has been conducted with participants of the VAP among agencies that received funding to replicate the program (Authors, 2023), no research has been conducted with VAP participants among agencies that did not receive funding. It would be interesting to compare the participant outcomes across the two types of replication to understand whether the availability of funding influenced participant outcomes.

Although organizations indicated access to other funding sources to continue to implement the VAP after the initial technical assistance process, it is unclear what supports would be needed for sustained implementation. Continued implementation of the VAP—regardless of whether seed funding is received or not—is crucial to understand the potential success of the VAP in being replicated across agencies. The large number of agencies motivated to replicate the VAP strongly suggest the interest and appeal of the advocacy program. However, research is needed to understand the feasibility of long-term implementation of the program.

Implications for Policy and Practice

With the next reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, the federal special education law in the United States) approaching, it is important to have a sense of whether practices such as advocacy, that have been recommended for inclusion (Gershwin, 2020) could be provided equitably across the United States. Our findings show that the infrastructure exists in the United States through established, funded family support agencies (e.g., PTIs, CPRCs) to incorporate an advocacy training component. In fact, our findings suggest that many of these agencies were already providing advocacy services and were looking for ways to increase capacity to meet an underserved need or community. Thus, it seems that advocacy which promotes equity should be reflected in the upcoming IDEA reauthorization.

However, replication of the VAP requires adaptations. For this reason, guidelines are needed to help agencies identify resources and infrastructure that should be in place before replicating the VAP (e.g., time, staff expertise), along with critical components of the VAP that should or should not be changed. For example, it may be required that agencies present the session on non-adversarial advocacy, in alignment with the core mission of the VAP (Author, 2016) and the importance of “ally advocates” (Mueller & Vick, 2019a). Additionally, agencies may need recommendations for required adaptions. For example, it may need to be a requirement that agencies update VAP content to reflect state-specific policies in addition to the federal law that is already included in existing curricular material.

Relatedly, policy and oversight continues to be needed to guide the unregulated field of special education advocacy (Goldman, 2020). As more agencies conduct the VAP or develop their own advocacy programs, more advocates will be available to families. Yet having a greater capacity of advocates is beneficial only if those advocates are prepared with the knowledge and skills needed to support family-school partnership through non-adversarial advocacy with an accurate understanding of special education law (Gershwin, 2020). Advocates without sufficient training can become adversarial or share inaccurate information and advice, harming the situation rather than serving as a support (Gershwin & Vick, 2019). Additionally, several agencies mentioned concerns regarding the unauthorized practice of law by advocates, who do not have a law degree. This distinction between lawyers and advocates has been highlighted throughout the development of the VAP and has also been identified as a common focus in other research (Gershwin & Vick, 2019).

Further, our finding that agencies are seeking to increase their capacity to attend IEP meetings with families shows that this persistent, well documented issue continues. Other policy solutions that complement parent advocacy should also be pursued to meet this need. Facilitated IEP meetings are another proactive method that can help overcome barriers to parent participation in IEP meetings (Mueller & Vick, 2019b), even when an advocate is not available to attend. This practice can build partnership and help prevent disagreements from developing into larger, adversarial issues (Mueller & Vick, 2019b) that need to be resolved through more formal safeguards delineated in IDEA.

In conclusion, this study presents a first, significant step toward understanding the motivation, process, and barriers to replication of a special education advocacy program. Even without funding, agencies were interested in replicating the VAP to serve a need in their community and many planned to continue to implement it, despite documented barriers. Only through replication can the effectiveness and generalizability of the VAP be understood.

References

Burke, M. M. (2013). Improving parental involvement: Training special education advocates. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23, 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207311424910

Burke, M. M., Mello, M. P., & Goldman, S. E. (2016). Examining the feasibility of a special education advocacy training program. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 28, 539–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-016-9491-3

Burke, M. M., Rios, K., & Lee, C. (2019). Exploring the special education advocacy process according to families and advocates. The Journal of Special Education, 5(3), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466918810204

Burke, M. M., Rossetti, Z., Rios, K., Schraml-Block, K., Lee, J., Aleman-Tovar, J. & Rivera, J. (2020). Legislative advocacy among parents of children with disabilities: Nature, strategies, and barriers. The Journal of Special Education, 5(3), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466918810204

Burke, M. M., Goldman, S. E., Li, C. (2022). A tale of two adaptations of a special education advocacyprogram. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Coyne, M. D., Cook, B. G., & Therrien, W. J. (2016). Recommendations for replication research in special education: A framework for systematic, conceptual replications. Remedial and Special Education, 37, 244–253.

Epley, P. H., Summers, J. A., & Turnbull, A. P. (2011). Family outcomes of early intervention: Families’ perceptions of need, services, and outcomes. Journal of Early intervention, 33(3), 201–219.

Gershwin, T., & Vick, A. M. (2019). Ally versus adversary behaviors: The utility of a special education advocate during conflict between parents and professionals. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 29(45), 195–205.

Gershwin, T. (2020). Legal and research considerations regarding the importance of developing and nurturing trusting family-professional partnerships in special education consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 30(4), 420–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2020.1785884

Goldman, S. E. (2020). Special education advocacy for families of students with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Current trends and future directions. International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities, 58, 1–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irrdd.2020.07.001

Goscicki, B. L., Goldman, S. E., Burke, M. M., & Hodapp, R. M. (2023). Applicants to aspecial education advocacy training program: “Insiders” in the disability advocacy world. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 61, 110–123.

Harry, B., & Ocasio-Stoutenburg, L. (2021). Parent advocacy for lives that matter. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 46(3), 184–198.

Hardy, A., Fulton, K., Kim, J., Li, C., Cheung, W., Burke, M. M., & Rossetti, Z. (under review). Examining parent testimonials for the reauthorization of the Individuals with DisabilitiesEducation Act.

Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2012). Why science is not necessarily self-correcting. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 645–654.

Jamison, J. M., Fourie, E., Siper, P. M., Trelles, M. P., George-Jones, J., Buxbaum, G., & Kolevzon, A. (2017). Examining the efficacy of a family peer advocate model for black and hispanic caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 1314–1322.

Krueger, R., Casey, M. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks, Richards, C. A., K., & Hemphill, M. A. (2009). A practical guide to collaborative qualitative data analysis. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37, 225–231.

Morrison, D. M., Hoppe, M. J., Gillmore, M. R., Kluver, C., Higa, D., & Wells, E. A. (2009). Replicating an intervention: the tension between fidelity and adaptation. AIDS Education & Prevention, 21(2), 128–140.

McLaughlin, T. W., Denney, M. K., Snyder, P. A., & Welsh, J. L. (2012). Behavior support interventions implemented by families of young children: Examination of contextual fit. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14(2), 87–97

Mueller, T. G., & Vick, A. M. (2019a). Ally versus adversary behaviors: The utility of a special education advocate during conflict between parents and professionals. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 29(4), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073198254

Mueller, T. G., & Vick, A. M. (2019b). An investigation of facilitated individualized education program meeting practice: Promising procedures that foster family-professional collaboration. Teacher Education and Special Education, 42(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/088840641773967

Richards, K. A. R., & Hemphill, M. A. (2018). A practical guide to collaborative qualitative data analysis. Journal of Teaching in Physical education, 37(2), 244–253.

Ruparelia, K., Abubakar, A., Badoe, E., Bakare, M., Visser, K., Chugani, D. C., Chugani, H. T., et al. (2016). Autism spectrum disorders in Africa: Current challenges in identification, assessment, and treatment: A report on the International Child Neurology Association Meeting on ASD in Africa. Journal of Child Neurology, 31, 1018–1026.

Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. (2013). Quantitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. Routledge.

Taylor, J. L., Hodapp, R. M., Burke, M. M., Waitz-Kudla, S. N., & Rabideau, C. (2017). Effects of a parent-training intervention on Service Access and Employment for Youth with ASD. Poster presentation presented at the Annual International Meeting for Autism Research.

Tenorio, M., Aparicio, A., Arango, P. S., Fernandez, A. K., Fergusson, A., Turull, J., & Pizarro, R. (2022). PaisDI: Feasibility and effectiveness of an advocacy program for adults with intellectual disability and their stakeholders’ groups in Chile. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 35, 633–638.

Tesch, R. (1990). Qualitative. Research: Analysis Types and Software. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315067339

Valdez, C. R., Abegglen, J., & Hauser, C. T. (2013). Fortalezas Familiares Program: Building sociocultural and family strengths in Latina women with depression and their families. Family process, 52(3), 378–393. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/famp.12008

Walmsley, J., Tilley, L., Dumbleton, S., & Bardsley, J. (2017). The changing face of parent advocacy: A long view. Disability and Society, 32, 1366–1386.

Funding

Meghan Burke securing the funding for this program. She spearheaded the development of the materials and collected all of the data except the interviews. She worked with Dr. Goldman to analyze the data and write the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Samantha Goldman collaborated with Dr. Burke to develop the study protocol. Dr. Goldman conducted the interviews. She worked with Dr. Burke to analyze the data and write the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

All agency representatives provided informed consent to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

There were no conflicts of interest in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burke, M.M., Goldman, S. Exploring the Motivation, Process, and Barriers for Replication of a Special Education Advocacy Program. J Dev Phys Disabil (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-024-09964-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-024-09964-6