Abstract

Our main purpose in this study was to investigate the levels of and the relationship between familiarity, confidence, training, and use of problem behavior interventions by special education teachers working with learners with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in school settings. A total of 80 special education teachers in South Carolina and Virginia completed an online survey. Results indicate a positive correlation between teachers’ familiarity, confidence, training, and use of problem behavior interventions. Across all intervention categories, providing choices, prompting, modeling, and direct instruction received the highest rankings for familiarity, confidence, and use. In addition, our results reveal that familiarity and confidence in implementing these interventions differs across groups of special education teachers based on years of experience. The most frequently reported factors that limit the use of problem behavior interventions in school settings were competing responsibilities, the need to involve multiple people, the amount of time required, and the difficulty using interventions during typical routines. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Learners with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often engage in self-injury, verbal or physical aggression, property destruction, tantrum, or noncompliance (Kurtz et al., 2011; Matson & LoVullo, 2008; Minshawi et al., 2014). Problem behavior displayed by learners with ASD has been attributed to various factors, including their reinforcement history, deficits in social-communication skills and adaptive behavior, sensory deficits, level of cognitive functioning, or co-morbid psychopathology (Holden & Gitlesen, 2006; Richards et al., 2012; Sigafoos, 2000). Learners with ASD who engage in problem behavior are more likely to have limited opportunities for inclusion in community settings and fewer friendships, experience social isolation, be placed in less inclusive educational settings, have health-related problems (Lory et al., 2020; Machalicek et al., 2007; Sigafoos et al., 2003; Wehmeyer et al., 2020) and, consequently, experience a low level of quality of life.

Learners with ASD engage in problem behavior at higher rates than typically developing learners (Matson et al., 2008) or learners with other developmental disabilities (Richards et al., 2012). Without effective interventions, problem behavior tends to persist across the lifespan as children with ASD transition into adolescence and adulthood (Murphy et al., 2005; Oliver & Richards, 2015; Taylor et al., 2011). Therefore, an important aspect of service delivery for learners with ASD in school settings is the adoption and use of empirically supported interventions (i.e., evidence-based practices [EBPs]) that decrease the likelihood of problem behavior and its negative consequences on their academic, behavioral, and social functioning while promoting the occurrence of socially acceptable behaviors. Moreover, federal mandates such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEIA, 2004) require teachers to implement effective interventions to address problem behavior that impedes students’ learning and to promote positive academic, behavioral, and social outcomes (Cook et al., 2013; Yell, 2019).

One group of interventions that have empirical support to document their effectiveness in preventing or reducing the frequency and severity of problem behavior in learners with ASD and other developmental disabilities consists of problem behavior interventions based on behavioral principles. At the core of problem behavior interventions is the notion that most problem behaviors are caused by antecedents (i.e., events that precede the behavior) and maintained by consequences (i.e., events that immediately follow the behavior) that are reinforcing or valuable for the learner displaying the behavior (Carr, 1977; Dunlap & Fox, 2011; Kern et al., 2002). In the behavioral literature, the sequence of events that precede and follow a behavior is called the three-term contingency. For example, a learner with ASD who is asked by their teacher to complete a complex academic task (antecedent), but lacks the prerequisite skills to successfully complete it, may engage in physical or verbal aggression (behavior) which results in the teacher removing the task (consequence). In this example, the learner may engage in physical and verbal aggression to escape or postpone the academic task presented by the teacher.

Researchers have demonstrated that conducting an assessment to identify and understand the antecedents that occur prior to a behavior and the consequences that strengthen or maintain the behavior leads to the development of more effective and efficient interventions (e.g., Carr & Durand, 1985; Dunlap & Fox, 2011; Filter & Horner, 2009; Ingram et al., 2005). Problem behavior interventions derived from assessment data that target problem behavior and the environmental events that evoke and maintain problem behavior consist of (a) antecedent-based interventions to prevent problem behavior or increase the likelihood of appropriate behavior, (b) instructional-based interventions to teach a replacement behavior that provides access to the same reinforcers or support the learner to engage in an existing appropriate behavior, and (c) consequence-based interventions to maximize reinforcement for the replacement or the existing appropriate behavior and minimize or withhold reinforcement for problem behavior (Cook et al., 2012).

Consider the case of a young learner with ASD who displays property destruction to obtain access to teacher’s attention. First, the teacher could use an antecedent-based intervention to prevent the occurrence of property destruction by placing the learner’s desk in their physical proximity and by providing frequent attention. Second, the teacher may use an instruction-based intervention such as prompting to teach the learner to appropriately request attention. However, if the learner knows how to request the teacher’s attention but does not perform the behavior, then an intervention such as social stories read at the beginning of the day could be a useful reminder to engage in appropriate behavior to obtain the teacher’s attention. Third, the teacher may use a consequence-based intervention by providing continuous reinforcement for displaying appropriate behavior and withholding reinforcement or extinction when the learner engages in property destruction to obtain attention.

Researchers have shown that problem behavior interventions that include multiple components targeting both antecedents and consequences that trigger and maintain problem behavior are more effective than interventions that focus on a single facet of the three-term contingency (Carr et al., 1999; Kern et al., 2002). Furthermore, although reinforcement-based interventions should be the first choice when addressing problem behavior, in some situations when the behavior is maintained by multiple environmental variables or is maintained by access to sensory sensations, punishment-based interventions such as response blocking or response interruption/response redirection may need to be considered (e.g., Chezan et al., 2017; Hagopian et al., 2015; Lang et al., 2009; Roscoe et al., 2013).

A large body of empirical evidence has documented the effectiveness of problem behavior interventions on preventing or reducing problem behavior displayed by learners with ASD and on increasing socially appropriate behaviors (e.g., Cook et al., 2012; Gregori et al., 2020; Rispoli et al., 2013; Watkins et al., 2019). In addition, researchers have demonstrated that teachers and paraprofessionals are able to implement problem behavior interventions when trained and these interventions have been effective in decreasing problem behavior and improving social-communication skills in learners with ASD when used by teachers in school settings (e.g., Goh et al., 2017; Machalicek et al., 2007; Walker & Snell, 2017; Walker et al., 2018). Despite the empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of problem behavior interventions when implemented by teachers in the classroom and their potential to improve learner outcomes, a research-to-practice gap exists as suggested by the limited adoption and use of such interventions in school settings. For example, researchers have indicated that many teachers use interventions that do not have empirical support documenting their effectiveness in producing positive student outcomes, implement interventions incorrectly and inconsistently (Brock et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2012; Odom et al., 2010), and do not use effective interventions on a regular basis (Landrum et al., 2003).

The research-to-practice gap or the discrepancy between EBPs and the interventions used by teachers in the classroom has been a recurring theme in the field of special education (Cook & Odom, 2013; Klingner et al., 2003). Using interventions that are not empirically supported to address the problem behavior displayed by learners in the classroom have been associated with negative consequences, such as coercive interactions between teachers and learners, maintenance of learners’ problem behavior, and low academic performance (Filter & Horner, 2009; Shores et al., 1993). Because of the negative consequences of the research-to-practice gap on learners’ academic and behavioral outcomes, numerous researchers have investigated the factors that contribute to the limited use of EBPs by teachers (e.g., Boudah et al., 2001; Gersten et al., 2000; Klingner et al., 2003).

Three factors that have been shown to impact the adoption and use of EBPs, including problem behavior interventions, by teachers in school settings consist of knowledge, confidence, and training on implementing these interventions. Findings of published studies on this topic suggest that teachers who are not confident in implementing EBPs are less likely to use them with learners with ASD in the classroom (Brock et al., 2014). Moreover, researchers have identified a positive correlation between knowledge, use, and social validity of EBPs implemented by early intervention providers and teachers. Specifically, early intervention providers and special education teachers who are more knowledgeable of EBPs use them more frequently in their practice (McNeill, 2019; Paynter et al., 2017), especially if they perceive them as socially valid. Furthermore, prior training and knowledge in ASD and EBPs have been shown to enhance educators’ confidence in working with learners with ASD and in using such interventions (Corona et al., 2017).

Collectively, the findings of the studies listed previously examining the use of EBPs by educators working with learners with ASD in school settings suggest that the adoption and implementation of these interventions is a complex process influenced by educators’ knowledge, confidence, and training in EBPs in addition to other factors, such as time, resources, cost, or limited feasibility of interventions in classroom settings (Alghamdi, 2021; Hsiao & Sorensen Petersen, 2019; Lang et al., 2010). Although the findings of these studies have advanced our understanding of the factors that may contribute to the research-to-practice gap and provided initial empirical evidence of the relationship between knowledge, confidence, and training on the use of EBPs with learners with ASD, several aspects require further investigation.

First, the authors of the studies listed previously examined the relationships between knowledge, confidence, and training on the use of EBPs in general without differentiating between interventions to promote academic success and interventions to address problem behavior in the classroom. Given the occurrence of problem behavior in learners with ASD in schools and the negative consequences on their quality of life and participation in inclusive educational settings, examining the impact of knowledge, confidence, and training on the adoption and use of problem behavior interventions may lead to more effective interventions and potential solutions for reducing the existing research-to-practice gap to address problem behavior displayed by learners with ASD. Academic instruction to promote students’ positive outcomes will be more difficult to implement if the problem behavior displayed by learners with ASD continues to occur in the school settings.

Second, EBPs were examined based on the description provided in the report published by the National Professional Development Center on ASD (NPDC; Wong et al., 2015) without differentiating between interventions targeting the antecedents and consequences facets of the three-term contingency. For example, antecedent-based interventions are a subgroup of EBPs that involve environmental changes prior to the occurrence of the problem behavior and are designed to promote appropriate behavior and reduce or prevent problem behavior. However, antecedent-based interventions encompass multiple interventions, such as modifications to task complexity or instructional delivery, providing choices, or environmental modifications that could be used to reduce the likelihood of problem behavior. Without a more in-depth analysis of the use of each intervention within a specific category and the factors that may hinder their implementation, it is possible that we do not have an accurate and complete understanding of why some interventions are less frequently used by teachers working with learners with ASD.

Third, the authors of the studies mentioned previously surveyed teachers regarding their knowledge, confidence, training, and use of EBPs listed in the NPDC report (Wong et al., 2015). Researchers have argued that teachers are more likely to adopt and use interventions that are feasible or have ecological validity (Gast, 2014; Ledford et al., 2016; Leko, 2014; Reid & Parsons, 2002). Therefore, it is important to examine whether interventions that have been implemented by teachers within the context of research studies are also used during daily practice with learners with ASD in the classroom. To address this aspect, we examined problem behavior interventions that have empirical support documenting teachers’ ability to implement the interventions with learners with ASD in school settings. Specifically, the problem behavior interventions included in this study were selected based on a literature review of research studies examining the effects of interventions on addressing the problem behavior of learners with ASD when interventions were implemented by teachers (Chezan et al., 2022). Finally, it is important to understand not only the relationship between knowledge, confidence, training, and use of problem behavior interventions but also additional factors that may hinder their implementation in school settings that may have not been previously discussed in the literature. One approach to accomplishing this goal is to offer teachers the opportunity to answer open-ended questions related to factors that limit their use of problem behavior interventions in school settings.

Thus, our purpose in this study was to extend the current literature on the use of EBPs by teachers working with learners with ASD in several ways. First, we examined the impact of teachers’ familiarity, confidence, and training on the use of problem behavior interventions with learners with ASD. Second, we investigated the adoption and use of problem behavior interventions that have been implemented with fidelity by teachers during typical activities in the classroom (i.e., ecologically valid interventions) in previously published studies. Third, we examined comprehensive interventions that addressed multiple facets of the three-term contingency (e.g., antecedent-based interventions, instruction-based interventions, and consequence-based interventions). Fourth, we examined whether teacher variables, such as experience, education, and graduation year influence their familiarity, confidence, and use of problem behavior interventions. Fifth, in addition to examining the factors reported previously in the literature as limiting the use of problem behavior interventions, we also collected qualitative data in the form of open-ended questions to obtain a more nuanced understanding of the variables that may limit the adoption and use of these interventions by teachers working with learners with ASD. Finally, we extended the current literature by examining the relationship between knowledge, confidence, training, and use of problem behavior interventions by special education teachers in two southeastern states (i.e., Virginia and South Carolina).

Method

Participants

Participants recruited for this study were special education teachers working with learners with ASD in school settings in two southeastern states in the United States. The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were (a) be at least 20 years of age, (b) be a special education teacher, (c) have worked with learners with ASD, and (d) have worked in a public school. We used several methods to recruit participants. First, we contacted the directors of special education services and principals across the two states to request their assistance with disseminating the survey to special education teachers in their school districts. Second, we posted an announcement on private and public social media websites. One original and two follow-up emails or social media postings were sent over 4 months to increase the number of responses. Regardless of the recruitment method and the type of announcement (i.e., original or follow up), we provided a description of the study purpose, the eligibility criteria, and the URL link to the survey.

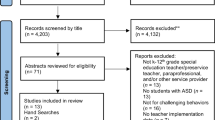

The study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board and all participants signed an electronic informed consent prior to participating in the study. A total of 191 special education teachers accessed the survey. However, only 80 surveys were completed and were included in the statistical analysis. Despite our efforts (i.e., follow-up emails, social media postings) to recruit a larger sample size of special education teachers, barriers related to restricted direct access to special education teachers, school districts research policies (e.g., only one email dissemination was allowed in some school districts), no response to our request from some directors of special education services and principals, the timing of survey administration (i.e., COVID-19), and the time needed to complete the survey (i.e., approximately 30 min) limited the number of teachers who received or completed the survey. Barriers related to contacting teachers directly have been mentioned in the literature as factors associated with limited sample sizes and response rates in education (McNeill, 2019). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the special education teachers who completed the survey. Most teachers were female (88.75%), White Non-Hispanic (76.25%), and had a master’s degree (56.15%). More than half of the teachers had over 10 years of experience and 80% of the teachers have taken courses in behavior analysis.

Instrument

We created a survey to examine the special education teachers’ familiarity, confidence, training, and frequency of use of problem behavior interventions with learners with ASD in schools. The problem behavior interventions included in the survey were based on a literature review of single-case research studies on interventions to prevent and address problem behavior in students with ASD (Chezan et al., 2022). We piloted the survey with three educators (i.e., two special education teachers and one administrator) working with learners with ASD and a faculty member with expertise in survey methodology. We asked the educators and faculty member to provide feedback on the clarity of questions, relevance, comprehensiveness, and time required to complete the survey. Based on the feedback received, we made several revisions related to the survey’s clarity and wording. The three educators were not included in the final sample of the study.

At the beginning of the survey, we provided a description of the research project and our purpose to examine the implementation of problem behavior interventions in the classroom. The survey consisted of 44 questions grouped in six sections: behavioral assessment (seven questions), antecedent-based interventions (seven questions), instruction-based interventions or teaching strategies (seven questions), reinforcement-based interventions and extinction (seven questions), punishment-based interventions (seven questions), and demographic data (nine questions). Each of the seven questions related to assessment or interventions included in the first five sections of the survey rated participants’ knowledge, familiarity, confidence, or use of multiple assessments or interventions. For example, the first question in the behavioral assessment section asked participants to rate their familiarity with four assessments (i.e., descriptive functional behavioral assessment [FBA], indirect FBA, functional analysis [FA], and discrete-trial functional analysis [DTFA]). The format of the first question was replicated across the remaining sections by asking participants to rate their familiarity with 11 antecedent-based interventions, eight instruction-based interventions, eight reinforcement-based interventions and extinction, and four punishment-based interventions for a total of 35 assessments and interventions.

We defined each section of the survey (e.g., behavioral assessment, antecedent-based interventions). For example, antecedent-based interventions were defined as strategies used to prevent the occurrence of learners’ problem behavior. We also defined and provided examples of each intervention (e.g., providing choices, mand training) included in a specific category. For example, providing choices was defined as presenting learners with two or more activities, items, or tasks and allowing them to choose which one to complete. An example would be showing learners a menu of three different one-digit addition worksheets from which they can choose the one to complete each day to prevent the occurrence of problem behavior maintained by escape from tasks. Each definition included in the survey was relatively short and ranged from 33 to 54 words. The survey included multiple-choice questions, 5-point Likert-type scale questions, and open-ended questions. The 5-point Likert scale consisted of scores from 0 (e.g., not at all confident) to 5 (e.g., extremely confident). A response was required to each question included in the survey. The survey took approximately 30 min to complete.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics (i.e., frequencies) to describe teachers’ demographic variables and the factors that hinder the use of problem behavior interventions in school settings. Ratings of familiarity, confidence, use, and training were analyzed and ranked for each of the 35 problem behavior interventions from the highest percentage of teachers reporting agreement with being familiar, having confidence, and receiving training on these interventions for learners with ASD within each problem behavior intervention category. Ratings of moderately, very, and extremely were considered indicators of high levels of familiarity and confidence and were summed for data analysis. We obtained percentages related to familiarity and confidence by identifying the number of teachers who rated a specific problem behavior intervention as moderately, very, and extremely (familiar or confident) and by dividing this number by the total number of teachers (N = 80) who completed the survey. We then ranked these percentages by assigning the rank of 1 to the problem behavior intervention that obtained the highest percentage of responses and the rank of 35 to the problem behavior intervention that obtained the smallest percentage of responses. For problem behavior interventions that had tied values (i.e., same percentage of responses), we reported the minimum corresponding rank. For example, modifications to task complexity, modifications to instructional delivery, and providing choices obtained the same percentage of responses (i.e., 96.25%) and received the same rank of 2 which represents the minimum corresponding rank. Ratings of not at all and slightly were also summed and considered indicators of low or no familiarity and confidence in implementing problem behavior interventions. This analysis was conducted for each problem behavior intervention-related responses received from the 80 special education teachers who completed the survey. The percentage of teachers implementing problem behavior interventions often (with more than 70% of students) and always (with 100% of students) was used as an indicator of frequent use of interventions to address problem behavior. For training, ratings of 4–10 h and 11 h or more were considered indicators of training on problem behavior interventions, whereas ratings of 0 h and 1–3 h were summed for data analysis and considered indicators of no or minimal training on problem behavior interventions. We used the same procedures described previously to calculate percentages and assign ranks for the use and training on problem behavior interventions.

We used Spearman rank-order correlations to examine the relationships among familiarity, confidence, training, and use of problem behavior interventions. To compare differences in familiarity, confidence, and use based on teachers’ demographic characteristics (i.e., education, graduation year, and experience), we combined the responses from all 80 teachers across the 35 problem behavior interventions and used the Wald-Type Statistics (WTS) analysis. The WTS is a nonparametric rank-based method that can be used as an alternative to the repeated measures ANOVA in those cases when the statistical assumptions of parametric methods are not met (Brunner et al., 2002; Noguchi et al., 2012). Specifically, WTS allows for the analysis of categorical data, and it is robust to outliers and small sample sizes (Brunner et al., 2002). If WTS indicated a statistically significant difference among groups, we conducted a post-hoc analysis to determine which groups accounted for the difference. Group comparisons were conducted using a combined dataset across all 35 problem behavior interventions. We compared the following groups: education (teachers holding a bachelor’s degree [BS] versus teachers holding a master’s degree [MS]); graduation year (teachers who graduated prior to or in 2004 versus teachers who graduated after 2004); and experience (teachers who worked between 0 and 3 years versus teachers who worked between 4 and 10 years versus teachers who worked 11 or more years). We selected 2004 as the graduation year mark, because IDEIA (2004) mandates that FBAs and implementation of EBPs should be used to address problem behavior displayed by learners with disabilities and, thus, had the potential to produce changes in educational practices implemented in schools.

We used thematic analysis consisting of generating codes, identifying, defining, and revising themes, and synthesizing and interpreting data to analyze the responses to the open-ended questions investigating the factors that limit the use of problem behavior interventions in school settings (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Hays & Singh, 2012). First, a trained doctoral student in a special education program and the first author read the responses to the open-ended questions included in the survey to become familiar with the qualitative data collected. Second, the doctoral student and the first author generated initial codes that emerged from the data and were informed by the focus of the question asked (e.g., consistency in intervention implementation, time consuming, limited training). Third, the first author checked the codes generated initially for accuracy and overlap, removed or combined codes when necessary, and developed a list of final codes. Third, the first author and the graduate student clustered the initial codes into potential themes (e.g., relationships) and subthemes (e.g., support, communication). Fourth, the first author and the doctoral student reviewed the themes by examining whether all codes within a theme provided a complete and accurate representation of teachers’ perceived barriers to problem behavior interventions’ use in schools. The codes were applied to all open-ended questions across all problem behavior interventions’ categories.

Results

Level of Familiarity, Confidence, Training, and Use of Problem Behavior Interventions

Teachers’ ratings of familiarity, confidence, training, and use of problem behavior interventions are displayed in Table 2. Interventions are listed by category (i.e., assessment, antecedent-based interventions, instructional-based interventions, reinforcement-based interventions and extinction, and punishment-based interventions) ranked from the highest percentage of teachers’ being familiar with the intervention to the lowest percentage in each category. The highest level of familiarity (91.25%), confidence (80%), use (32.5%), and amount of training (61.25%) in behavioral assessment was reported for descriptive FBA. Although a large percentage of teachers reported being familiar (75%) and confident (65%) and receiving training (57.5%) in FA, this method was rarely used (20%) by teachers included in this study. In the category of antecedent-based interventions, teachers reported that providing choices was the most familiar (96.25%) and most used (83.75%) intervention and they were confident (93.75%) in implementing it with their learners. Compared to other antecedent-based interventions, response satiation, response deprivation, and interspersal training were the least familiar (77.5%; 76.25%; and 76.25%) and less often used (40%; 38.75%; and 43.75%) interventions that teachers used to prevent the occurrence of problem behavior in their students with ASD.

The three most frequently used instructional-based interventions were direct instruction (80%), prompting (78.75%), and modeling (77.5%). Teachers also reported that they were most familiar with prompting (97.5%), modeling (96.25%), and direct instruction (96.25%) and were very confident in implementing them (95%; 93.75%, and 93.75%). The most training received on instructional-based interventions was also reported for direct instruction (80%), prompting (78.75%), and modeling (77.5%). Mand training received the lowest rankings for familiarity (76.25%), confidence (32%), training (51.25%), and use (37.5%) in the instructional-based interventions category. In the category of reinforcement-based interventions and extinction, continuous and intermittent reinforcement were the most familiar (92.5%) interventions that teachers received training on (66.25%) and were confident (91.25%; 90%) in implementing it with their learners; however, token economy was the most frequently (66.25%) used intervention in this category. Chained schedules of reinforcement were the least familiar (80%) and rarely (33.75%) used interventions for which teachers reported a low implementation confidence level (72.5%) and training (56.25%). In the category of punishment-based interventions, response interruption/response redirection (Wong et al., 2015) was the most familiar (83.75%) and often used (43.75%) intervention that teachers were confident (77.5%) implementing, whereas positive practice overcorrection was the least familiar (68.75%) and rarely used (28.75%) intervention. Across all problem behavior interventions, the four highest ranked interventions in familiarity, confidence, and use were prompting, modeling, direct instruction, and providing choices, whereas DTFA was ranked lowest in familiarity and confidence and second lowest used after FA.

Relationships Between Familiarity, Confidence, Training, and Use of Problem Behavior Interventions

Table 3 displays the Spearman rank-order correlations between familiarity, confidence, use, and training on problem behavior interventions. Data revealed positive and significant correlations between familiarity, confidence, and use of problem behavior interventions suggesting that when teachers are more familiar with problem behavior interventions, they are more confident in implementing these interventions (φ = 0.980, p < 0.001***), and more likely to use them frequently in their classrooms (φ = 0.838, p < 0.001***). Spearman rank-order correlations also indicated positive and significant relationships between training, familiarity, confidence, and use of problem behavior interventions. Specifically, results revealed that teachers who receive more training on problem behavior interventions are more familiar with such interventions (φ = 0.902, p < 0.001***), have a higher level of confidence in implementing problem behavior interventions (φ = 0.914, p < 0.001***), and use them more frequently (φ = 0.861, p < 0.001***).

Group Comparisons

Table 4 shows differences in familiarity, confidence, and use of problem behavior interventions among teachers with different demographic characteristics. WTS results indicated that groups of teachers did not differ significantly in familiarity, confidence, and use of problem behavior interventions based on education and graduation year. However, familiarity and confidence differed significantly across groups of teachers based on years of experience. Overall, teachers with 3 or less years of experience rated their familiarity and confidence in using problem behavior interventions significantly lower than teachers with 4 to 10 years of experience and teachers with 11 or more years of experience. Results of the post-hoc analysis displayed in Table 5 showed that teachers with 3 or less years of experience reported less familiarity (t = 9.776, p < 0.001***) and confidence (t = 11.852, p < 0.001***) in implementing problem behavior interventions compared to teachers with 4 to 10 years of experience. Furthermore, teachers with 3 or less years of experience reported less familiarity (t = 12.003, p < 0.001***) and confidence (t = 16.591, p < 0.001***) in implementing problem behavior interventions compared to teachers with 11 or more years of experience. Results indicated no significant difference in familiarity and confidence in implementing problem behavior interventions between teachers with more experience (i.e., 10 or less years of experience versus 11 or more years of experience).

Factors That Limit the Use of Problem Behavior Interventions

Across all problem behavior intervention categories, thematic analysis of qualitative data revealed five main themes related to factors that limit the use of these interventions by teachers: expertise, resources, relationships, prioritization, and implementation. Expertise indicated the lack of knowledge and insufficient or no training on specific problem behavior interventions and was perceived by teachers as a critical barrier (e.g., “Many teachers need more training on why and how behavioral assessments are used. Some do not understand the purpose.”; “The reason I may not use these interventions is due to not knowing when to apply a strategy or having a systematic process as to when to use a strategy, assessment, or process.”). The qualitative data were augmented by the quantitative data collected through closed-ended questions which revealed insufficient or no training as one of the factors that hinders the use of specific problem behavior interventions, including FA and DTFA, antecedent-based interventions (i.e., demand fading, noncontingent reinforcement [NCR], response satiation, response deprivation, and interspersal training), reinforcement-based interventions (i.e., chained schedules), and all punishment-based interventions. Detailed information on the percentage of responses across problem behavior interventions and factors that limit their use in the school settings is reported in the supplemental materials (Tables 6 – 10).

Limited resources were the second theme identified and included subthemes related to limited material and human resources (e.g., “Generally, the need for quality behavioral assessment is much greater than the available resources”), competing responsibilities (e.g., “Multiple students with individual behavior concerns and other tasks to complete at the same time”), and amount of time required to implement problem behavior interventions (e.g., “Requires lots of preparation with minimal time to plan/make materials”). Relationships among teachers and learners’ families was also perceived as a barrier that limited the use of problem behavior interventions with learners with ASD. Subthemes identified in this category included the lack of communication and support from families, such as no feedback or involvement in their children’s behavior support plan or denial to provide consent for behavioral assessment. For example, one teacher stated that “Some parents do not give information about outside factors that could be affecting students’ behaviors in school,” whereas another teacher stated that “Some parents are difficult and not willing to assist or deny consent to assess.”

Prioritization of problem behavior also emerged as a theme that explained the less frequent use of some problem behavior interventions compared to others. For example, one participant stated that “I would say the nature and severity of the interfering or challenging behavior determines the need to conduct a behavioral assessment. In other words, behavioral assessments are often prioritized to students with more serious problem behavior (bx that is dangerous), such as self-injurious behavior, aggression, property destruction, and elopement. Those behaviors are prioritized over less interfering behaviors, such as cursing or calling out.” Implementation of problem behavior interventions was also a theme relevant to factors that restrict the adoption and use of these interventions by the special education teachers in this study. Several subthemes identified within this category included lack of consistent implementation of problem behavior interventions across staff members (e.g., “Large teams of people working in the room and not all staff implement interventions consistently”) and fidelity of implementation (e.g., “The fidelity of intervention implementation across professionals that work with the student can vary, limiting the effectiveness of intervention success.”).

Quantitative data collected through closed-ended questions included in the survey that asked teachers to select from a predetermined list of factors that may hinder the use of problem behavior interventions in school settings provided additional information. Figure 1 displays the average percentage of responses across problem behavior intervention categories. Detailed information on each factor and each problem behavior intervention is included in the supplemental materials. Competing responsibilities, the amount of time required, the need to involve multiple people, and difficulty to implement problem behavior interventions during typical activities in the school setting were the most frequently reported factors that limit the use of these interventions across all categories. Cost and difficulty of problem behavior intervention use by teachers were the least frequently reported factors associated with the adoption and implementation of these interventions in school settings across all categories except for the instruction-based interventions category for which cost was reported as limiting the use of their use in schools.

Although difficulty to use problem behavior interventions during typical activities in the classroom was rated as one of the factors limiting the use of FBA, antecedent-based interventions, reinforcement-based interventions and extinction, and punishment-based interventions, it was not rated by teachers as a factor that limits the use of instruction-based interventions with a few exceptions. Specifically, teachers reported that social stories, Picture Exchange Communication Systems (PECS), and discrete-trial training (DTT) were difficult to use during typical activities in the classroom. Difficulty to use problem behavior interventions in schools was not frequently rated as a factor limiting the use of these interventions in the school except for two assessments (i.e., FA and DTFA), five antecedent-based interventions (i.e., demand fading, NCR, response satiation, response deprivation, and interspersal training), extinction, and three punishment-based interventions (i.e., response cost, response blocking, and positive practice overcorrection). Teachers also reported that another professional was responsible for implementing specific problem behavior interventions, including FBA, antecedent-based interventions (i.e., interspersal training, demand fading), instruction-based interventions (i.e., PECS, DTT, functional communication training [FCT], and mand training), reinforcement-based interventions (i.e., delay to reinforcement), and extinction.

Discussion

Our purposes in this study were to: (a) determine the levels of familiarity, confidence, training, and use of problem behavior interventions by special education teachers working with learners with ASD in South Carolina and Virginia, (b) identify the relationship between teachers’ familiarity, confidence, and training on the use of problem behavior interventions in school settings, (c) compare the level of familiarity, confidence, and use across teachers based on their level of education, graduation year, and experience, and (d) identify the factors that limit the use of problem behavior interventions by special education teachers in school settings. Results revealed that across all problem behavior interventions providing choices, prompting, modeling, and direct instruction received the highest rankings in familiarity, confidence, and use. Modeling and prompting were also reported as frequently used interventions in previous studies (Paynter et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2018; McNeill, 2019) which is an indicator of their large adoption by educators working with learners with ASD.

Although most teachers reported being familiar with and confident in implementing descriptive and indirect FBA, these assessments were rarely used by the special education teachers in this study. This finding is consistent with previous reports in the literature indicating that despite high levels of knowledge and social validity of FBA, this practice is not used frequently by special education teachers (McNeill, 2019). One potential explanation for this finding may be that FBA is a process conducted to identify the function of the problem behavior prior to the selection and implementation of interventions that target the identified function and, consequently, it is less frequently used in daily practice (Hanley, 2012; Wong et al., 2015). Another potential explanation may be that special education teachers are not responsible for conducting FBA in some school districts or they may not be required to use both descriptive FBA and indirect FBA to collect data for all students who engage in problem behavior (Weber et al., 2005). Future studies may investigate the role of special education teachers in conducting assessments in schools and examine whether the low frequency of usage is an artifact of its characteristics (i.e., one-time process versus daily implementation).

One question that remains unanswered in this study is whether the low ranking for the use of FBA leads to the implementation of less effective interventions. For example, several teachers reported that some parents do not provide informed consent for the assessment to be conducted in those situations when the learner engages in problem behavior that impacts their learning or the learning of others. Nevertheless, we did not collect information to examine if teachers proceed with the implementation of interventions without conducting an assessment in such situations or other approaches are being used to address problem behavior. Future studies should investigate how parent or student-related factors may prevent the implementation of problem behavior interventions and impact the quality and effectiveness of these interventions and of behavior support plans.

Considering the findings related to the limited use of FBA as reported by teachers in this study, we would like to highlight the critical importance of developing interventions derived from assessment data. A large body of empirical evidence has documented that problem behavior interventions derived from assessment data are more effective than problem behavior interventions that are not data-based driven when addressing problem behavior in learners with disabilities (e.g., Carr et al., 1999; Hanley et al., 2003; Ingram et al., 2005; Sugai et al., 1999; Walker et al., 2018). Problem behavior interventions not linked to assessment data usually produce little or no changes in learners’ problem behavior and result in the development of ineffective behavior change programs (Dunlap & Kern, 2018). For example, a teacher who withholds attention when a learner engages in property destruction to access their preferred activity will have limited success in changing the learner’s behavior because attention does not represent the consequence that maintains property destruction. However, if the teacher implements an assessment data-based problem behavior intervention consisting of providing (a) frequent access to the preferred item (antecedent-based intervention) and (b) longer and immediate access to the preferred item when the learner asks for the item appropriately and no access when the learner engages in property destruction (consequence-based interventions) will likely be successful in changing the learner’s problem behavior. Thus, it is critical both for researchers and for practitioners to further examine innovative approaches leading to the development of high-quality problem behavior interventions derived from assessment data to promote learner success.

Teachers in this study reported low rankings of familiarity, confidence, training, and use of several antecedent-based interventions, namely response satiation, response deprivation, and interspersal training that address a learner’s motivation to engage in socially appropriate behaviors while decreasing the likelihood of problem behavior. One potential explanation for the less frequent use of antecedent-based interventions such as response satiation, response deprivation, and interspersal training may be that these interventions are not appropriate for all problem behaviors displayed by learners with ASD in the school setting. For example, interspersal training consists of combining easy tasks with more complex tasks to enhance a learner’s motivation to engage in a specific task may be appropriate for problem behavior maintained by escape from academic demands; however, it may have no relevance for behaviors maintained by attention or access to preferred items or activities. Considering the unique characteristics of the sample of special education teachers (i.e., 80% of the teachers had training in applied behavior analysis) included in this study, it is surprising that they reported insufficient training, limited familiarity, and low confidence in using these antecedent-based interventions. A learner’s motivation plays a critical role in the occurrence of problem behavior and engagement in socially appropriate behavior; thus, it is important for researchers to identify effective approaches to promote the use of interventions that have the potential to prevent the occurrence of problem behavior by decreasing the learner’s motivation to engage in problem behavior.

One finding that warrants further discussion relates to the four interventions (i.e., providing choices, prompting, modeling, and direct instruction) that received the highest rankings in familiarity, confidence, and use. Providing choices is an antecedent-based intervention usually implemented to prevent the occurrence of problem behavior maintained by escape from tasks and requires minimal training to use it with fidelity during typical classroom activities. Therefore, it is expected that teachers are likely to provide choices to their learners throughout the school day to reduce the likelihood of problem behavior. However, it is surprising that prompting, modeling, and direct instruction also received the highest ranking in familiarity, confidence, and use across all problem behavior interventions. These interventions are used to teach a replacement behavior that provides access to the same consequence as problem behavior. Prompting and modeling have been reported in previous studies as EBPs that teachers, school psychologists, and health professionals are familiar with and confident in using (Brock et al., 2014; McNeill, 2019; Paynter et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2018). One potential explanation for the high ranking of these interventions is that teachers in this study rated prompting, modeling, and direct instruction as interventions used in their classroom to address a variety of academic, social, and behavioral goals even though they were informed about the purpose of this study and its focus on problem behavior interventions to address challenging behavior. Replications of this study with a larger sample of special education teachers are needed to further investigate whether prompting, modeling, and direct instruction are used consistently by teachers within the context of interventions targeting problem behavior displayed by learners with ASD rather than across a variety of academic, social, and behavioral goals.

A promising finding is the low ranking for use of punishment-based interventions by special education teachers working with learners with ASD in school settings. This finding is encouraging considering the professional and ethical concerns associated with the use of aversive procedures with learners with ASD. For example, one of the ethical and professional responsibilities of special education teachers is to protect the psychological and physical well-being of learners with disabilities and refrain from engaging in practices that have the potential to harm them (Council of Exceptional Children, 2020). Because of the side effects associated with the use of punishment, such as emotional and aggressive reactions, and escape and avoidance, and their long-lasting effect and possible psychological harm for the learner, it is recommended that teachers and other school professionals consider first reinforcement-based interventions prior to using punishment (Cooper et al., 2020).

It is noteworthy that more training on problem behavior interventions increases teachers’ familiarity and confidence in implementing these interventions and, consequently, their frequent use with learners with ASD. These findings are consistent with previous studies that examined the relationship between teachers’ knowledge, confidence, and use of EBPs with learners with ASD (Alghamdi, 2021; McNeill, 2019; Paynter et al., 2017). Furthermore, several teachers in this study mentioned the lack of knowledge and training, the inconsistency in using problem behavior interventions across staff members, and low implementation fidelity as critical barriers to the use of these interventions in the classroom. Because of the potential contribution of training to the adoption and use of problem behavior interventions and their implementation with fidelity, it is imperative that teacher preparation programs and professional development activities focus on providing evidence-based training in implementing problem behavior interventions. Researchers have demonstrated that training teachers on how to implement EBPs to address problem behavior displayed by learners with ASD improves not only their knowledge but also their confidence and self-efficacy in providing services to this population of learners (Barnhill et al., 2014; Corona et al., 2017).

Contrary to a previous study’s findings (McNeill, 2019), our results suggested that teachers with 3 or less years of experience are less familiar and confident in implementing problem behavior interventions compared to teachers with over 4 years of experience. One potential explanation for this finding may be the different focus of the survey administered in this study (i.e., problem behavior interventions) compared to the focus of the survey in the McNeill (2019) study (i.e., EBPs in general). It is possible that the implementation of problem behavior interventions to address problem behavior requires a higher level of familiarity and confidence than the implementation of EBPs to promote skill acquisition and academic learning. Therefore, teachers who have a longer history of implementing problem behavior interventions are more familiar with and confident in using problem behavior interventions compared to teachers who have no or limited experience in using problem behavior interventions in the classroom. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution because of the small number (n = 10) of teachers with 3 or less years of experience who completed the survey. The small number of teachers with less experience may not be representative of all teachers with similar levels of experience and, thus, may have biased the results. Future studies need to replicate this study with a larger and more representative sample of teachers with less experience to further investigate the relation between familiarity, confidence, and teaching experience. Additional research is also needed to examine if and how the adoption and use of EBPs to promote academic success versus the adoption and use of EBPs to address problem behavior are influenced by teacher-related variables.

One of the most frequently reported factors that impedes the adoption and use of problem behavior interventions in school settings is the need to involve multiple staff members to implement these interventions. This finding mirrors those reported by Chezan et al. (2022) in their study examining the ecological validity of research studies on problem behavior interventions for children with ASD in schools. Chezan and colleagues identified the involvement of multiple individuals in the implementation of problem behavior interventions as one of the factors that limited the feasibility of their implementation in schools. The authors also emphasized the need to develop innovative approaches to increase the ecological validity of problem behavior interventions and, thus, allow teachers to use interventions that are both effective and match the human resources available in school settings. The feasibility of implementation of EBPs, including problem behavior interventions, has been identified as one of the factors that limits the adoption and use of specific interventions by teachers in the school setting (Cook et al., 2008; Klingner et al., 2013). Future studies should explore how the feasibility of problem behavior interventions can be increased by addressing the concerns related to limited human resources and other factors that may promote their implementation by teachers during typical activities in the classroom.

The findings of this study have several implications for practice. First, given that teachers reported the frequent use of only four problem behavior interventions, it is critical that training and professional development focus on providing teachers the knowledge and skills needed to implement a wide-range of interventions to prevent and reduce problem behavior in learners with ASD while addressing the concerns related to their limited feasibility during typical activities in the classroom. Because of the negative consequences associated with problem behavior on learners’ progress and access to inclusive educational environments, equipping teachers with the skills needed to address problem behavior may be an avenue for promoting learner success and positive outcomes. Second, effective, evidence-based training provides teachers not only the opportunity to acquire theoretical knowledge but also the opportunity to apply problem behavior interventions in their classrooms while receiving feedback and on-going support. Training approaches, such as practice-based coaching, behavior skills training, or telepractice have been effective in promoting the acquisition and use of EBPs (Conroy et al., 2015; Fairburn & Cooper, 2011; Kirpatrick et al., 2019) and, thus, can be used to train teachers how to implement problem behavior interventions with fidelity.

The findings of this study should be interpreted with caution within the context of several limitations. First, we administered an electronic survey to special education teachers without implementing strategies to measure the accuracy of their responses. Therefore, we do not know whether the responses analyzed provide accurate and complete information on the status of problem behavior interventions used by the teachers in this study. Future studies could include observational data in addition to teacher self-reports to obtain a more accurate and complete understanding of the implementation of problem behavior interventions in schools. Second, the survey contained a list of problem behavior interventions identified in a literature review on the ecological validity of interventions for children with ASD (Chezan et al., 2022). It is possible that teachers used additional practices in their classrooms that were not included in the survey.

Third, we recruited a relatively small sample of special education teachers in Virginia and South Carolina and, thus, our findings may not be representative of a larger population of special education teachers working with learners with ASD. Replication of this study need to be conducted to generalize the findings to a larger population of special education teachers across the United States. Fourth, the number of special education teachers who completed the survey in South Carolina was very small and did not allow us to conduct any comparisons on the level of familiarity, confidence, training, and use across the two states.

Fifth, because the survey was disseminated with the assistance of special education directors and principals and advertised on social media, we do not know the number of teachers who received the survey, and we were unable to calculate the response rate. Barriers related to contacting teachers directly have been mentioned in the literature as factors associated with limited sample sizes and response rates (McNeill, 2019). Finally, most of the special education teachers who completed the survey were White Non-Hispanic females and had taken courses in applied behavior analysis. Although these data are consistent with demographic data reported in previous studies (Burns & Ysseldyke, 2009), our sample may not be representative of all special education teachers working with learners with ASD especially in rural areas.

In conclusion, the findings of our study suggest that, across all problem behavior interventions, providing choices, prompting, modeling, and direct instruction received the highest rankings in familiarity, confidence, and use. Furthermore, response satiation and deprivation, interspersal training, mand training, chained schedules of reinforcement, and positive practice overcorrection received the lowest rankings in familiarity, confidence, training, and use. Although most teachers reported being familiar with and confident in implementing descriptive FBA and continuous and intermittent reinforcement, these practices were less frequently used. A positive correlation between teachers’ familiarity, confidence, training, and use of problem behavior interventions was also demonstrated suggesting that teachers who are more familiar and received training on problem behavior interventions implementation are more confident and likely to use these interventions in their classrooms. In addition, teachers with less experience reported less familiarity and confidence in implementing problem behavior interventions compared to teachers with more experience. The most frequently reported factors that limit the use of problem behavior interventions in the school settings were competing responsibilities, the need to involve multiple staff members, and the amount of time needed to implement these interventions.

References

Alghamdi, A. S. (2021). Training teachers to implement evidence-based practices specifically designed for students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Education and Practice, 12(17), 7–16.

Barnhill, G. P., Sumutka, B., Polloway, E. A., & Lee, E. (2014). Personnel preparation practices in ASD: A follow-up analysis of contemporary practices. Focus on Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 29(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1088357612475294

Boudah, D., Logan, K., & Greenwood, C. (2001). The research to practice projects: Lessons learned about changing teacher practice. Teacher Education and Special Education, 24(4), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F088840640102400404

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brock, M. E., Dynia, J. M., Dueker, S. A., & Barczak, M. A. (2020). Teacher-reported priorities and practices for students with autism: Characterizing the research-to-practice gap. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 35(2), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1088357619881217

Brock, M. E., Huber, H. B., Carter, E. W., Juarez, A. P., & Warren, Z. (2014). Statewide assessment of professional development needs related to educating students with autism spectrum disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29(2), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1088357614522290

Brunner, E., Domhof, S., & Langer, F. (2002). Nonparametric analysis of longitudinal data in factorial experiments. Wiley.

Burns, M. K., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2009). Reported prevalence of evidence-based instructional practices in special education. The Journal of Special Education, 43(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0022466908315563

Carr, E. G. (1977). The motivation of self-injurious behavior: A review of some hypotheses. Psychological Bulletin, 84(4), 800–816. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.4.800

Carr, E. G., & Durand, V. M. (1985). Reducing problem behaviors through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111

Carr, E. G., Horner, R. H., Turnbull, A. P., Marquis, J., Magito-McLaughlin, D., McAtee, M. L., Smith, C. E., Ryan, K. A., Ruef, M. B., & Doolabh, A. (1999). Positive behavior support for people with developmental disabilities: A research synthesis. American Association on Mental Retardation.

Chezan, L. C., Gable, R., McWhorter, G. Z., & White, S. (2017). Current perspectives on interventions for self-injurious behavior of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Behavioral Education, 26, 293–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-017-9269-4

Chezan, L. C., McCammon, M. N., Drasgow, E., & Wolfe, K. (2022). The ecological validity of research studies on function-based interventions in schools for children with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Modification, 46(1), 202–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445520964921

Conroy, M. A., Sutherland, K. S., Algina, J. J., Wilson, R. E., Martinez, J. R., & Whalon, K. J. (2015). Measuring teacher implementation of the BEST in CLASS intervention program and corollary child outcomes. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 23(3), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426614532949

Cook, B. G., & Odom, S. L. (2013). Evidence-based practices and implementation science in special education. Exceptional Children, 79(3), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F001440291307900201

Cook, B. G., Cook, L., & Landrum, T. J. (2013). Moving research into practice: Can we make dissemination stick? Exceptional Children, 79, 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291307900203

Cook, B. G., Tankersley, M., Cook, L., & Landrum, T. J. (2008). Evidence-based special education and professional wisdom: Putting it all together. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1053451208321566

Cook, C. R., Mayer, G. R., Browning Wright, D., Kraemer, B., Wallace, M. D., Collins, T., & Restori, A. (2012). Exploring the link among behavior intervention plans, treatment integrity, and student outcomes under natural educational conditions. The Journal of Special Education, 46, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466910369941

Cooper, O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied Behavior Analysis (3rd edition). Pearson.

Corona, L. L., Christodulu, K. V., & Rinaldi, M. L. (2017). Investigation of school professionals’ self-efficacy for working with students with ASD: Impact of prior experience, knowledge, and training. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1098300716667604

Council for Exceptional Children (2020, August 14). K-12 initial standards and components. Retrieved from: https://exceptionalchildren.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/K12%20Initial%20Standards%20and%20Components.pdf

Dunlap, G., & Fox, L. (2011). Function-based interventions for children with challenging behavior. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(4), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815111429971

Dunlap, G., & Kern, L. (2018). Perspectives on functional (behavioral) assessment. Behavioral Disorders, 43(2), 316–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0198742917746633

Fairburn, C. G., & Cooper, Z. (2011). Therapist competence, therapy quality, and therapist training. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(6–7), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.005

Filter, K. J., & Horner, R. H. (2009). Function-based academic interventions for problem behavior. Education and Treatment of Children, 32(1), 1–20. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42900004

Gast, D. L. (2014). General factors in measurement and evaluation. In D. L. Gast & J. R. Ledford (Eds.), Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences (2nd ed., pp. 85–104). Routledge.

Gersten, R., Chard, D., & Baker, S. (2000). Factors enhancing sustained use of research-based instructional practices. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33, 445–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F002221940003300505

Goh, A. E., Drogan, R. R., & Papay, C. K. (2017). Function-based interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders in schools: A review. International Journal of Special Education, 32(1), 115–133.

Gregori, E., Wendt, O., Gerow, S., Peltier, C., Genc-Tosun, D., Lory, C., & Gold, Z. S. (2020). Functional communication training for adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and quality appraisal. Journal of Behavioral Education, 29, 42–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-019-09339-4

Hagopian, L. P., Rooker, G. W., & Zarcone, J. R. (2015). Delineating subtypes of self-injurious behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48, 523–543. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.233

Hanley, G. P. (2012). Functional assessment of problem behavior: Dispelling myths, overcoming implementation obstacles, and developing new lore. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 51(1), 54–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391818

Hanley, G. P., Iwata, B. A., & McCord, B. E. (2003). Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(2), 147–185. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings (1st ed.). Guilford Press.

Holden, B., & Gitlesen, J. P. (2006). A total population study of challenging behaviour in the country of Hedmark, Norway: Prevalence, and risk markers. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27, 456–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2005.06.001

Hsiao, Y. J., & Sorensen Petersen, S. (2019). Evidence-based practices provided in teacher education and in-service training programs for special education teachers of students with autism spectrum disorder. Teacher Education and Special Education, 42(3), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0888406418758464

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, 20 U. S. C. ξ1400 et seq. (2004).

Ingram, K., Lewis-Palmer, T., & Sugai, G. (2005). Function-based intervention planning: Comparing the effectiveness of FBA function-based and non-function-based intervention plans. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 7(4), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F10983007050070040401

Kern, L., Choutka, C. M., & Sokol, N. G. (2002). Assessment-based antecedent interventions used in natural settings to reduce challenging behavior: An analysis of the literature. Education and Treatment of Children, 25(1), 113–130. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42900519

Kirkpatrick, M., Akers, J., & Rivera, G. (2019). Use of behavioral skills training with teachers: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Education, 28(3), 344–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-019-09322-z

Klingner, J. K., Ahwee, S., Pilonieta, P., & Menendez, R. (2003). Barriers and facilitators in scaling up research-based practices. Exceptional Children, 69(4), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F001440290306900402

Klingner, J. K., Boardman, A. G., & McMaster, K. L. (2013). What does it take to scale up and sustain evidence-based practices? Exceptional Children, 79(3), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F001440291307900205

Kurtz, P. F., Boelter, E. W., Jarmolowicz, D. P., Chin, M. D., & Hagopian, L. P. (2011). An analysis of functional communication training as an empirically supported treatment for problem behavior displayed by individuals with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 2935–2942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.05.009

Landrum, T., Tankersley, M., & Kauffman, J. (2003). What is special about special education for students with emotional and behavioral disorders? The Journal of Special Education, 37(3), 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F00224669030370030401

Lang, R., O’Reilly, M. F., Sigafoos, J., Machalicek, W., Rispoli, M., Shogren, K., Chan, J., M., Davis, T., Lancioni, G., & Hopkins, S. (2010). Review of teacher involvement in the applied intervention research for children with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45(2), 268–283. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23879811

Lang, R., Rispoli, M., Machalicek, M., White, P. J., Kang, S., Pierce, N., Mulloy, A., Fragale, T., O’Reilly, M., Sigafoos, J., & Lancioni, J. (2009). Treatment of elopement in individuals with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(4), 670–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2008.11.003

Ledford, J. R., Hall, E., Conder, E., & Lane, J. D. (2016). Research for young children with autism spectrum disorders: Evidence of social and ecological validity. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35, 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121415585956

Leko, M. M. (2014). The value of qualitative methods in social validity research. Remedial and Special Education, 35, 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932514524002

Lory, C., Mason, R. A., Davis, J. L., Wang, D., Kim, S. Y., Gregori, E., & David, M. (2020). A meta-analysis of challenging behavior interventions for students with developmental disabilities in inclusive school settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 1221–1237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04329-x

Machalicek, W., O’Reilly, M. F., Beretvas, N., Sigafoos, J., & Lancioni, G. E. (2007). A review of interventions to reduce challenging behavior in school settings for students with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1(3), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2006.10.005

Matson, J. L., & LoVullo, S. V. (2008). A review of behavioral treatments for self-injurious behaviors of persons with autism spectrum disorders. Behavior Modification, 32(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507304581

Matson, J. L., Wilkins, J., & Macken, J. (2008). The relationship of challenging behaviors to severity and symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Mental Health Research, 2(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315860802611415

McNeill, J. (2019). Social validity and teachers’ use of evidence-based practices for autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 49, 4585–4594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04190-y

Minshawi, N., Hurwitz, S., Fodstad, J., Biebl, S., Morris, D., & McDougle, C. (2014). The association between self-injurious behaviors and autism spectrum disorders. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 7, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S44635

Murphy, G. H., Beadle-Brown, J., Wing, L., Gould, J., Shah, A., & Holmes, N. (2005). Chronicity of challenging behaviours in people with severe intellectual disabilities and/or autism: A total population sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(4), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-005-5030-2

Noguchi, K., Gel, Y. R., Brunner, E., & Konietschke, F. (2012). nparLD: An R software package for the nonparametric analysis of longitudinal data in factorial experiments. Journal of Statistical Software, 50(12), 1–23.

Odom, S. L., Collet-Klingenberg, L., Rogers, S. J., & Hatton, D. D. (2010). Evidence-based practices in interventions for children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Preventing School Failure, 54(4), 275–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459881003785506

Oliver, C., & Richards, C. (2015). Practitioner review: Self-injurious behaviour in children with developmental delay. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 1042–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12425

Paynter, J. M., Ferguson, S., Fordyce, K., Joosten, A., Paku, S., Stephens, M., Trembath, D., & Keen, D. (2017). Utilisation of evidence-based practices by ASD early intervention service providers. Autism, 21(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1362361316633032

Reid, D. H., & Parsons, M. B. (2002). Working with staff to overcome challenging behavior among people who have severe disabilities: A guide for getting support plans carried out. Habilitative Management Consultants.

Richards, C., Oliver, C., Nelson, L., & Moss, J. (2012). Self-injurious behaviour in individuals with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56, 476–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01537.x

Rispoli, M., Ganz, J., Neely, L., & Goodwyn, F. (2013). The effect of noncontingent positive versus negative reinforcement on multiply controlled behavior during discrete trial training. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities, 25(1), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-012-9315-z

Robinson, L., Bond, C., & Oldfield, J. (2018). A UK and Ireland survey of educational psychologists’ intervention practices for students with autism spectrum disorder. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34(1), 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1391066

Roscoe, E. M., Iwata, B. A., & Zhou, L. (2013). Assessment and treatment of chronic hand mouthing. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46, 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.14

Shores, R. E., Gunter, P. L., & Jack, S. L. (1993). Classroom management strategies: Are they setting events for coercion? Behavioral Disorders, 18(2), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F019874299301800207

Sigafoos, J. (2000). Communication development and aberrant behavior in children with developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Mental Retardation & Developmental Disabilities, 35, 168–176.

Sigafoos, J., Arthur, M., & O’Reilly, M. (2003). Challenging behavior and developmental disability. Paul H. Brookes.

Sugai, G. M., Horner, R. H., & Sprague, J. R. (1999). Functional assessment-based behavior support planning: Research-to-practice-to-research. Behavioral Disorders, 24, 223–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F019874299902400309

Taylor, L., Oliver, C., & Murphy, G. (2011). The chronicity of self-injurious behaviour: A long-term follow-up of a total population study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 24, 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2010.00579.x

Walker, V. L., & Snell, M. E. (2017). Teaching paraprofessionals to implement function-based interventions. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 32(2), 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1088357616673561

Walker, V. L., Chung, Y. C., & Bonnet, L. K. (2018). Function-based intervention in inclusive school settings: A meta-analysis. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(4), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1098300717718350

Watkins, L., Ledbetter-Cho, K., O’Reilly, M., Barnard-Brak, L., & Garcia-Grau, P. (2019). Interventions for students with autism in inclusive settings: A best-evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 145(5), 490–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000190

Weber, K. P., Killu, K., Derby, K. M., & Barretto, A. (2005). The status of functional behavioral assessment (FBA): Adherence to standard practice in FBA methodology. Psychology in the School, 42(7), 747–744. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20108

Wehmeyer, M. L., Shogren, K. A., & Kurth, J. (2020). The state of inclusion with students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the United States. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 18(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12332

Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K. A., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., Brock, M., Plavnik, J. B., Fleury, V. P., & Schultz, T. R. (2015). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45(7), 1951–1966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2351-z

Yell, M. L. (2019). The law and special education (5th ed.). Pearson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Research Involving Human Participants

Approval from the university Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to beginning the study.

Informed Consent

All participants signed an electronic informed consent prior to completing the online survey. All procedures in this study were performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note