Abstract

Family caregivers make significant contributions to the overall care of cancer patients and are the “invisible backbone” of the health care system. Family caregivers experience a wide range of challenges and can be considered patients in their own right, requiring support and dedicated attention, which may benefit them, the patients they are caring for, and the health care system. Despite consistent evidence on caregiver distress and unmet needs, most cancer care is organized around the patient as the target of care and caregiver distress is not screened for or addressed systematically. This article describes the development of a novel clinical, educational, and research program dedicated to supporting family caregivers at the Princess Margaret Cancer Center, Toronto, Canada and presents a model for a brief psychosocial intervention for caregivers. The objective of this article is to assist others in developing services to address the needs of family caregivers as a standard of care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Family caregivers make significant contributions to the overall care of cancer patients and can be seen as the “invisible backbone” of the health care system. Health care system navigation, information access, liaison with medical personnel, transportation, economic aid, and physical and emotional support for cancer patients are provided by these informal caregivers and formal health care systems could not function without their efforts. Moreover, the trends toward longer survival and more ambulatory and home care of cancer patients increase the importance of their family caregivers and the length of time that family caregivers devote to providing care (Gladjchen, 2004).

Consistent evidence shows that family caregivers are not only our partners in care, but that they may be patients in their own right. Family caregivers experience a wide range of psychological, spiritual, social, financial, and physical challenges and have been shown to have psychological distress that is disproportionate to the general population, especially when caring for individuals with advanced cancer (Götze et al., 2018; Grande et al., 2018; Rumpold et al., 2016). Studies that assessed concurrently patients and family caregivers also report that psychologically, family caregivers may experience more distress than the patients they are caring for (Kershaw et al., 2015). One of the first studies to assess patients and their family caregivers concurrently was conducted in our cancer hospital, the Princess Margaret (PM) Cancer Centre, in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. In this study, Braun and colleagues (Braun et al., 2007) found that almost 40% of spousal caregivers endorsed depressive symptoms, compared to only 23% of their advanced ill spouses.

Despite this significant “hidden morbidity” (Braun et al., 2007), most cancer care is organized around the patient as the target of care and caregiver distress is not screened for or addressed systematically (Deshields & Applebaum, 2015). While the family has long been acknowledged to be the focus of pediatric care and palliative care (Hudson et al., 2012; Kearney et al., 2015), there are numerous systemic obstacles to the consideration of caregiver needs in adult cancer hospitals. However, where family-oriented care is part of the hospital model of care and culture, it may improve satisfaction with care on the part of patients and families, improve patient health outcomes and decrease utilization of health care resources, and lead to higher health care staff ratings of work satisfaction (Clay & Parsh, 2016).

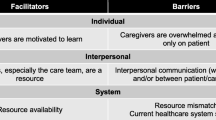

In order to understand how we can address caregiver needs in our institution, we conducted focus groups with current and bereaved family caregivers of advanced cancer patients of the PM (Nissim et al., 2017). In these focus groups, we asked about caregiver intervention needs, caregiver-perceived barriers to intervention access and completion, and ideas on how to address these barriers. All focus group participants emphasized that support for caregivers is an important, yet neglected, issue and wished for a resource within the cancer hospital that they can access without the patient and that is focused on their own needs as caregivers. They agreed that such resource could challenge the shame and guilt they felt about their own needs and emotions and allow them to express concerns that they could not freely express in the presence of the patient. Additionally, participants stressed the importance of health care providers being more proactive about offering caregiver services and finding out caregiver needs.

Subsequently, a dedicated Caregiver Clinic was launched in 2017. Our clinic philosophy is that caregiver well-being is a shared responsibility of the family caregiver and the cancer care system and that caregiver well-being should be utilized as an actionable indicator of cancer care quality. The objective of this review is to summarize the genesis and brief history of our Caregiver Clinic and provide an overview of our clinical, education, and research initiatives, in order to assist other centers in expanding their own efforts to recognize and attend to the needs of family caregivers. Of note, the Caregiver Clinic currently supports over 150 family caregivers per year. Quantitative data on program implementation and outcomes will be reported in a subsequent paper.

Clinical Care

The Caregiver Clinic operates within the Psychosocial Oncology (PSO) clinic of the PM Department of Supportive Care. The PM is Canada’s leading cancer center serving over 13,000 new patients every year. The PSO clinic supports cancer patients by referral. It includes specialists in social work, psychiatry, psychology, and art therapy, as well as trained peer volunteers. The Caregiver Clinic is currently staffed by one full-time psychologist and one part-time psychology post-doctoral fellow and is supported by other existing PSO administrative and clinical resources. Funding for the Caregiver Clinic clinical services is primarily provided by philanthropic support through the PM Foundation.

The Caregiver Clinic offers one-on-one counseling services. We strategically decided not to provide group-based supports because in Ontario, both Wellspring (www.wellspring.ca) and Gilda’s Club (www.gildasclubtoronto.org) have developed support groups and workshops that cancer patients and their families can attend. Therefore, our focus is on offering individual support, which is not as available for caregivers.

Below, we provide an overview of the referral, intake, and intervention strategies we have developed.

Referral

The Caregiver Clinic accepts referrals for adult family caregivers of adult cancer patients treated at the PM. Any health care provider affiliated with the PM can refer caregivers to our clinic. Caregivers can also self-refer by calling the PSO clinic front desk, if they do not wish to disclose their distress to the patient’s health care team. Other referral criteria include caregiver-related distress or difficulty coping. In order to avoid duplication of services, caregivers are asked at the point of referral if they are already connected with a therapist in the community for individual support. If they are, they are redirected back to this resource. Caregivers who fall outside of our referral criteria are provided with information about community resources for family caregivers.

Our priority is to serve caregivers who are caring for patients who do not require or are not interested in a referral to the PSO clinic for themselves. If both the patient and the caregiver are interested in a referral for psychosocial support, one of our PSO specialists will see them together to assess and triage and will refer the caregiver to the Caregiver Clinic only if they establish that the caregiver requires psychosocial support separate from what they can provide (e.g., if patient’s psychiatric symptoms or significant relational conflict limit the benefit of joint sessions).

In order to protect the caregiver’s personal health information, when a referral to the Caregiver Clinic is accepted, the caregivers are issued their own medical record number so that the documentation of the care they receive is kept separately from the patients’ health records. The practice of generating separate medical records for caregivers also facilitates communication with other health care providers who support the caregiver and documentation of any support provided after the death of the patient. In addition, while our clinical services are currently provided without cost to caregivers, separate medical records allow us to bill for uncovered services (e.g., completion of insurance disability certificates).

Intake

The initial face-to-face appointment with the family caregiver follows a standard PSO intake process and is designed to gather information to assess the needs and preferences of the caregiver and formulate a plan that addresses their treatment goals. The intake process includes questions about the well-being of the caregiver, the caregiver’s perception of the health and prognosis of the patient, the consequences of caregiving on the caregiver, the caregiving circumstances and demands, and the social network available to support the caregiver. With the understanding that the psychological trauma associated with cancer in the family may re-activate previous trauma, special attention is given to gathering information about past traumatic experiences, as well as information about coping tools and resources that were helpful for the caregiver then and now. The intake session also includes obtaining informed consent to receive care and release information to the patient’s medical team, as needed, to optimize care for both the patient and the caregiver.

The intake session may be the only session that the caregiver attends. For some caregivers, this is because the follow-up plan involves a transition to other support resources, but for most caregivers, especially those who care for patients at the end of life, it is because they do not have the capacity to attend more than one session given their caregiving demands and other responsibilities. With this in mind, we aim to proactively interweave the three key tasks of our caregiver intervention (described below) within the intake information gathering process.

Intervention

Based on ours and others’ research on caregivers’ support needs (Nissim et al., 2017; Treanor, 2020; Ugalde et al., 2019), our growing clinical experience with caregivers and lessons from our evidence-based psychotherapeutic intervention for patients, referred to as Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM; Rodin et al., 2018), we designed an integrated, tailored psychosocial intervention for caregivers of cancer patients, regardless of disease stage, which involves three key tasks: (1) Legitimatization of the caregiver’s needs and distress; (2) Facilitation of double awareness and attending to grief reactions; and (3) Increasing caregiver’s self-efficacy. Each therapeutic task is described in detail below, along with the rationale for its conceptualization, and how it is carried out in sessions.

Legitimizing and Normalizing Caregiver’s Distress

Family caregivers tend to dismiss their own distress and needs. This tendency, previously described in the literature as self-silencing or protective buffering (Perndorfer et al., 2019; Ussher & Perz, 2010; Wertheim et al., 2018), has been identified consistently as a barrier to caregivers’ access to psychosocial support (Carduff et al., 2014; Crotty et al., 2020; Nissim et al., 2017; Tranberg et al., 2019) and as associated with increased distress (Perndorfer et al., 2019; Tranberg et al., 2019; Wertheim et al., 2018). Our focus group study with caregivers (Nissim et al., 2017) taught us that even when caregivers access formal or informal support resources, they may still be hesitant to share their emotions and needs fully and openly or they may feel shame or guilt when doing so. We, therefore, proactively aim to normalize caregiver distress. Normalizing starts with the intake session by making sure that every question we ask is framed in a way that validates their distress. For example, when we ask about trauma history, we stress that the psychological trauma of cancer is experienced by the entire family unit and is not limited to the family member with the cancer diagnosis, and when we ask caregivers to quantify or describe their own distress, we use this question as an opportunity to share with them the consistent evidence that psychologically, family caregivers often experience more distress than the patients they are caring for.

In addition to normalizing the fact that family caregivers may experience more distress than the patients they are caring for, we attempt to uncover in sessions what may contribute to this disproportionate distress. We offer caregivers the observation that, paradoxically, individuals often experience more powerlessness and helplessness when they are in the position of the caregiver than the patient, and if this resonates with them, we help them reflect on how the sense of helplessness manifests for them. Similarly, we share that because caregivers do not have the same direct access that patients have to getting answers (and often reassurance) from the health care team, they often have more unmet information needs, which may increase their distress. We also invite caregivers to examine how they are responding to their own distress. We normalize the tendency to dismiss or be critical of their own distress and needs, but we also discuss the added burden that comes from it and how it may prevent engagement in self-care. Our goal is to help caregivers move away from labeling self-care as “selfish” and recognize that actions to improve their health, maintain optimal functioning, and increase general well-being may benefit the patient as well. Of note, the existence of a caregiver clinic within a cancer hospital by itself is validating to family caregivers and encourages them to privilege their own needs.

Facilitating Double Awareness and Attending to Grief Reactions

The concept of double awareness (Rodin & Zimmermann, 2008) has been first used in the context of advanced cancer and has informed our CALM psychotherapy for this patient population (Colosimo et al., 2018; Rodin et al., 2018). It refers to living with the awareness of impending death and balancing this awareness against staying engaged in life. In working with caregivers, we have found that the framework of double awareness can help them navigate the emotional landscape of their experience, regardless of the patient’s cancer stage and prognosis. We present this framework to caregivers, usually at the intake session, and invite them to explore how it may apply to their circumstances. We begin by explaining that cancer, regardless of its estimated prognosis, robs patients and family caregivers alike from the illusions of certainty and control and unveils the existential reality of uncertainty; and uncertainty, by default, brings about a duality of hope and fear. Our goal is to help caregivers consider hope and fear as inherently co-existing and to normalize the back and forth movement between the two. The framework of double awareness allows us to proactively validate current (or future) thoughts about the possibility of death and position them as a fluctuating experience within the duality of fear and hope. It helps caregivers give themselves permission to verbalize their fears and create and action on contingency plans for worst-case scenarios, including plans for the patient’s death and for life after the patient dies, without associating the consideration of these possibilities with “giving up” (an association that often elicits shame and guilt).

Similarly to our CALM protocol (Rodin et al., 2018), we may invite the patient or other family members for a one-off joint session to explore how the duality of hope and fear impacts the family system. However, this is not always possible or indicated. Often, when caregivers allow themselves to verbalize and process their fears in individual sessions, they are then better able to respond to or initiate a discussion with the patient or other family members about their shared fears and hopes.

The framework of double awareness helps us explore with caregivers the many current or anticipatory tangible and intangible losses associated with a cancer diagnosis in the family. In addition to discussing fears related to dying and death (An et al., 2020), we discuss other tangible losses such as a loss of income or fertility and intangible or ambiguous losses, namely losses that caregivers experience on an ongoing basis and that are often not recognized or legitimized as they are not as clearly definable or certain as death (Betz & Thorngren, 2006). Common intangible losses that we discuss with caregivers include the loss of the illusion of certainty or the loss of the vision (whether it was implicit or explicit) that one had for the future. These numerous current and anticipatory losses elicit grief reactions that need to be labeled as such and attended to. We proactively provide psychoeducation to caregivers about grief as a common experience, which, like fear, can be positioned as a normal and fluctuating experience that co-exists with hope, and we explore with them if and how grief is present in their lives. We also explain that grief may be what underlies more accessible emotions, such as anger or guilt (Tie & Poulsen, 2013). Caregivers are often surprised to realize how much grief they are carrying. Caregivers caring for patients at the end of life realize that their experience entails grief even before the patient dies and caregivers caring for patients who completed curative treatment come to understand that the end-of-treatment phase brings with it not only a sense of relief and joy, but also grief for the many losses and changes brought by the cancer diagnosis and its treatment.

Enhancing Self-efficacy

A strong predictor of psychological distress in family caregivers is low self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is an important variable in cognitive appraisal theories of stress and coping and refers, in the context of caregiving, to the confidence they have in their ability to provide care (Hudson, 2013). We address self-efficacy in caregivers by helping them prioritize and strategize caregiving tasks as well as tasks related to other stressors (e.g., role changes or financial difficulties), identify and access appropriate resources within the PM and in the community, and understand how to navigate the health care system effectively. We also aim to help caregivers negotiate the shifts in roles within the family that the illness often brings and understand and meet support needs of other family members and the responses of their wider social network. Lastly, consistent with our goal of legitimizing caregiver’s own needs and distress, we pay special attention to caregivers’ self-efficacy in relation to self-care, e.g., by exploring with them which achievable strategies they can employ to enhance their own well-being.

Ultimately, when caregivers no longer criticize themselves for their needs and fears, acknowledge and process their grief and feel more capable, other therapeutic opportunities emerge, including the exploration of how caregiving may increase emotional closeness with the patient, be a source of meaning and growth, and become a life chapter that is positive, satisfying, and empowering.

Intervention Format

We believe that the three key tasks described above can be attained in either individual, dyadic, or group interventions for caregivers. We strategically decided not to provide group-based supports because we are fortunate at the PM to be able to refer caregivers to excellent community-based support centers that offer group programs regularly and free of charge. Likewise, while we may invite the patient for a one-off dyadic session, our focus is on offering individual support, which is not as available for caregivers. The individual format allows us greater flexibility in adapting the number of sessions to the needs and circumstances of the caregivers and in offering a tailored experience to help meet constantly changing needs across the full cancer trajectory, including the bereavement phase. While our intervention has a strong psychoeducation component, the individual format helps us provide it within a relational stance, with curiosity about the worldview and culture of the individual that is not prescriptive. The individual format is expanded as needed to support the entire family unit. When we conduct sessions with the caregiver and patient together or with the entire family, our three therapeutic tasks are presented in the context of broader family dynamics.

Education

The Caregiver Clinic functions as a hub for the education of health care professionals who desire more knowledge and training in addressing caregiver distress. Trainees may come from diverse disciplines, including oncology, family medicine, palliative care, and mental health and may join us for training ranging from a brief observership or a 2-year fellowship. Our trainees receive exposure to what is often a new population for them while our clinic benefits by having additional staff available to support caregivers.

We also offer training and education in collaboration with community agencies and other PSO initiatives within the PM, such as the CALM Clinic and Training Program. The CALM clinic offers our brief, evidence-based CALM psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with advanced cancer (Rodin et al., 2018). As part of the CALM intervention, patients are encouraged to invite their family members to at least one session. The CALM training program is a specialized weekly training program to teach and supervise health care professionals in the provision of CALM. The Caregiver Clinic staff support this training by supervising CALM trainees on the needs and distress of caregivers of patients with advanced cancer and how to deliver CALM sessions that include the family caregiver.

We are also working closely with the PM Cancer Education program to produce educational materials for health care providers and family caregivers on caregiver distress and helpful coping tools and community resources. Our webpage, which is updated regularly, provides information on available community resources for family caregivers of patients that are treated within and outside the PM. Lastly, we developed a variety of outreach activities to extend information and services for caregivers beyond the PM, including partnering with the Cancer Care Ontario working group to develop a provincial Oncology Caregiver Support Framework.

Research

The Caregiver Clinic is an important venue for research, essentially acting as a “living lab,” in which our clinical work with a large volume of caregivers helps us identify gaps in knowledge and care and in which we can implement and test new clinical solutions. This is in line with the push–pull infrastructure model that has been proposed to help address the general disconnect between empirical work and clinical practice in PSO and optimize evidence-based psychosocial care (Jacobsen, 2009). According to this model, our clinic can be viewed as the “infrastructure” that enables both the production of relevant scientific knowledge (“push”) and efforts to increase the demand and use of its clinical application (“pull”).

Our active integrated research program is primarily funded by extramural funding and serves to complement our clinical goals and support expanded service provision and increased program visibility within our institution. Our current research program includes studies on caregiver distress and bereavement outcomes in the context of medical assistance in dying and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic; validating interventions for fear of cancer recurrence in family caregivers; developing and testing an online version of the CALM intervention for family caregivers; and piloting a nurse-led distress screening and a stepped care pathway for family caregivers of patients who are seen by the PM outpatient palliative care clinic. These lines of research stem directly from our clinical practice with family caregivers and all resulted in extramural funding.

Discussion

We have described a novel caregiver support initiative, which we have developed into a comprehensive clinical, educational, and research program. Although growing research attention has been dedicated to informal caregivers’ distress and unmet needs, to the best of our knowledge little attention has been paid to the development of a systematic clinical solution. Our model of care may assist other centers in expanding their own efforts to address this gap in care.

Our clinical arm offers a personalized tailored approach to identify caregivers’ needs, provide resources, and promote their well-being. Our clinical strategy was informed by a preliminary focus group study with family caregivers of cancer patients attending our center (Nissim et al., 2017). An important goal in conducting this study was to understand factors that hinder support for caregivers and that may challenge the feasibility of a new support service for this population. Our findings suggested that the main barrier that prevented caregivers from accessing existing PSO resources was that these resources were only available to them if the patient was also interested in PSO support and wished for the caregiver to be involved. This systemic barrier is common to many cancer centers and PSO programs (Deshields & Nanna, 2010; Hudson, 2013) and can be addressed by creating a resource that caregivers can access on their own and can self-refer to, if needed, so that their access is not dependent on the patient’s interest in (or ability to) receive psychosocial support.

Essential to our ability to create a resource dedicated to caregivers was the establishment of separate medical records for caregivers once they are referred to our clinic. This practice allows us to protect the privacy and confidentiality of both patients and caregivers and to continue to document caregiver support in bereavement. As others suggest, the implementation of caregiver records is a key foundational step in creating support resources for caregivers, not only because it is a necessary infrastructure for billing and documentation, but also because separate documentation may encourage caregivers to access resources and speak more freely and openly about their needs and distress (Applebaum et al., 2021; Longacre et al., 2018; Mosher et al., 2015).

Our clinical intervention with family caregivers includes three key tasks: (1) legitimatization of the caregiver’s needs and distress; (2) facilitation of double awareness and attending to grief reactions; and (3) increasing caregiver’s self-efficacy. We aim to attend to these tasks from the get-go, during the intake session, because caregivers, and especially those who are caring for patients at the final weeks of life, may have limited time or respite to engage in more than one session. A single-visit intervention is not unique to caregivers. Cancer patients’ symptomatology or other difficulties may also prevent them from attending more than one session, and PSO programs are often limited to brief interventions (Deshields & Nanna, 2010; Hamann & Kendall, 2013), with previous research suggesting that therapeutic needs can be addressed effectively in a single PSO visit (Powell et al., 2008).

Our primary therapeutic task is the validation and normalization of distress. This task is central to all PSO interventions (Deshields & Nanna, 2010) but it may be even more important with family caregivers. Caregivers routinely put their own physical or mental challenges on the back burner, dismiss, or feel guilty about their distress and may attempt to protect the patient from upset by denying any cancer-related distress of their own (Crotty et al., 2020; Nissim et al., 2017; Tranberg et al., 2019). Of note, implementing a caregiver-focused program as standard of care within a cancer center may contribute to normalizing and destigmatizing caregivers’ distress. Our second therapeutic task focuses on supporting meaning-making processes by introducing caregivers to the framework of double awareness. This framework, borrowed from previous work with individuals with advanced cancer (Rodin et al., 2018), helps caregivers verbalize and make sense of their experience as they cope with the uncertainty that a cancer diagnosis brings. Our intervention also focuses on enhancing caregiver’s self-efficacy. Caregivers have a strong need for a sense of mastery and control in providing care. In studies with current and bereaved caregivers (Crotty et al., 2020; Hudson et al., 2002; Nissim et al., 2017), caregivers described themselves as assuming the role of the project manager in relation the patient’s disease and consistently expressed a strong wish for more guidance regarding this overwhelming responsibility. Importantly, increased self-efficacy in caregivers is also associated with more post-traumatic and post-loss growth for caregivers (Lee et al., 2016) and increased survival for patients (Boele et al., 2017).

Our clinic allows us to create unique educational opportunities in clinical practice and research that benefit trainees but are also useful for our program and support its sustainability. Our education efforts include outreach activities, production of relevant education materials, and in-house training for staff and trainees from diverse disciplines in order to improve their skills in providing psychosocial care for caregivers. These efforts help with the promotion of the Caregiver Clinic and with improving its visibility within and outside the PM. Our dedicated caregiver clinic also serves as a living research lab. The opportunity to see a large volume of caregivers allows for a clinical recognition of gaps in care and for testing and validating new clinical tools to address these deficiencies. In this regard, our clinic offers a unique solution to the fact that evidence-based interventions for caregivers are seldom translated into practice (Northouse et al., 2012; Ugalde et al., 2019).

Our extramurally funded research studies enable us to pilot future expansions of our clinical activities. We are currently piloting a stepped care pathway for caregivers in collaboration with the PM outpatient palliative care clinic (Hannon et al., 2015). Stepped care has been validated with cancer patients and may be feasible and effective with their caregivers we well (Laidsaar-Powell et al., 2019). We selected the outpatient palliative care clinic as our pilot site as we identified it as a high-need site in which we already have good uptake and relationships. If successful, this step care model can be adopted by other high-need clinics, such as our neuro-oncology clinic, in which a family-oriented model of care is also paramount (Page & Chang, 2017).

Our Caregiver Clinic has been fortunate to have generous philanthropic support, without which its development would not have been possible. Vital for program sustainability with finite resources is the integration of the clinic’s operational processes into existing institutional infrastructure. The clinic is situated within the PSO clinic and is leveraging the infrastructure, services and expertise available within the PSO clinic, and other program at the PM and in the community. Sustainability is also supported by the development of a brief model of care, which is often provided in a single visit. Lastly, our ability to generate fundable caregiver research aligns us with the priorities of our academic cancer center and supports our clinical services; our preliminary focus group study with family caregivers (Nissim et al., 2017) helped us advocate for a dedicated clinic for caregivers, and our current research studies help us test novel ways to expand care delivery.

Summary

Family caregivers function as an invisible, albeit critical, part of the health care workforce to meet care needs of individuals with cancer. As our health care systems ask caregivers to shoulder more and more responsibilities, it is increasingly recognized that complete care of the cancer patient includes the family caregiver and that a paradigm shift from patient-centered to family-oriented care is needed. We aimed to provide a comprehensive practice blueprint for the design of a clinical service for family caregivers within a cancer hospital and to encourage other institutions to consider the psychosocial well-being of the family caregiver as a legitimate focus of hospital cancer care.

Data Availability

N/A.

Code Availability

N/A.

References

An, E., Wennberg, E., Nissim, R., Lo, C., Hales, S., & Rodin, G. (2020). Death talk and relief of death-related distress in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 10, e19.

Applebaum, A. J., Kent, E. E., & Lichtenthal, W. G. (2021). Documentation of caregivers as a standard of care. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 39, 1955–1958.

Betz, G., & Thorngren, J. M. (2006). Ambiguous loss and the family grieving process. Family Journal (alexandria Va.), 14, 359–365.

Boele, F. W., Given, C. W., & Given, B. A. (2017). Family caregivers’ level of mastery predicts survival of patients with glioblastoma: A preliminary report: Caregiver mastery and patient survival. Cancer, 123, 832–840.

Braun, M., Mikulincer, M., Rydall, A., Walsh, A., & Rodin, G. (2007). Hidden morbidity in cancer: Spouse caregivers. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 25, 4829–4834.

Carduff, E., Finucane, A., Kendall, M., Jarvis, A., Harrison, N., Greenacre, J., & Murray, S. A. (2014). Understanding the barriers to identifying carers of people with advanced illness in primary care: Triangulating three data sources. BMC Family Practice, 15, 48.

Clay, A. M., & Parsh, B. (2016). Patient- and family-centered care: It’s not just for pediatrics anymore. AMA Journal of Ethics, 18, 40–44.

Colosimo, K., Nissim, R., Pos, A. E., Hales, S., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. (2018). Double awareness” in psychotherapy for patients living with advanced cancer. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 28, 125–140.

Crotty, B. H., Asan, O., Holt, J., Tyszka, J., Erickson, J., Stolley, M., Pezzin, L. E., & Nattinger, A. B. (2020). Qualitative assessment of unmet information management needs of informal cancer caregivers: Four themes to inform oncology practice. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics, 4, 521–528.

Deshields, T. L., & Applebaum, A. J. (2015). The time is now: Assessing and addressing the needs of cancer caregivers: Assessing needs of cancer caregivers. Cancer, 121, 1344–1346.

Deshields, T. L., & Nanna, S. K. (2010). Providing care for the “whole patient” in the cancer setting: The psycho-oncology consultation model of patient care. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 17, 249–257.

Gladjchen, M. (2004). The emerging role and needs of family caregivers in cancer care. The Journal of Supportive Oncology, 2, 145–155.

Götze, H., Brähler, E., Gansera, L., Schnabel, A., Gottschalk-Fleischer, A., & Köhler, N. (2018). Anxiety, depression and quality of life in family caregivers of palliative cancer patients during home care and after the patient’s death. European Journal of Cancer Care, 27, e12606.

Grande, G., Rowland, C., van den Berg, B., & Hanratty, B. (2018). Psychological morbidity and general health among family caregivers during end-of-life cancer care: A retrospective census survey. Palliative Medicine, 32, 1605–1614.

Hamann, H. A., & Kendall, J. (2013). Growing a psychosocial oncology program within a cancer center. Oncology Issues, 28, 32–39.

Hannon, B., Swami, N., Pope, A., Rodin, G., Dougherty, E., Mak, E., Banerjee, S., Bryson, J., Ridley, J., & Zimmermann, C. (2015). The oncology palliative care clinic at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre: An early intervention model for patients with advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 23, 1073–1080.

Hudson, P. (2013). Improving support for family carers: Key implications for research, policy and practice. Palliative Medicine, 27, 581–582.

Hudson, P., Aranda, S., & McMurray, N. (2002). Intervention development for enhanced lay palliative caregiver support: The use of focus groups. European Journal of Cancer Care, 11, 262–270.

Hudson, P., Remedios, C., Zordan, R., Thomas, K., Clifton, D., Crewdson, M., Hall, C., Trauer, T., Bolleter, A., Clarke, D. M., & Bauld, C. (2012). Guidelines for the psychosocial and bereavement support of family caregivers of palliative care patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15, 696–702.

Jacobsen, P. B. (2009). Promoting evidence-based psychosocial care for cancer patients: Promoting evidence-based psychosocial care. Psycho-Oncology, 18, 6–13.

Kearney, J. A., Salley, C. G., & Muriel, A. C. (2015). Standards of psychosocial care for parents of children with cancer: Standards of psychosocial care for parents of children with cancer. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62, S632–S683.

Kershaw, T., Ellis, K. R., Yoon, H., Schafenacker, A., Katapodi, M., & Northouse, L. (2015). The interdependence of advanced cancer patients’ and their family caregivers’ mental health, physical health, and self-efficacy over time. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 49, 901–911.

Laidsaar-Powell, R., Butow, P., & Juraskova, I. (2019). Recognising and managing the psychosocial needs of family carers: It’s time for change. Patient Education and Counseling, 102, 401–403.

Lee, Y. J., Choi, Y. S., Hwang, I. C., Kim, H. M., & Hwang, S. W. (2016). Resilience at the end of life as a predictor for postloss growth in bereaved caregivers of cancer patients: A prospective pilot study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51, e3–e5.

Longacre, M. L., Applebaum, A. J., Buzaglo, J. S., Miller, M. F., Golant, M., Rowland, J. H., Given, B., Dockham, B., & Northouse, L. (2018). Reducing informal caregiver burden in cancer: Evidence-based programs in practice. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 8, 145–155.

Mosher, C. E., Given, B. A., & Ostroff, J. S. (2015). Barriers to mental health service use among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients: Barriers to mental health service use. European Journal of Cancer Care, 24, 50–59.

Nissim, R., Hales, S., Zimmermann, C., Deckert, A., Edwards, B., & Rodin, G. (2017). Supporting family caregivers of advanced cancer patients: A focus group study: Family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Family Relations, 66, 867–879.

Northouse, L., Williams, A. L., Given, B., & McCorkle, R. (2012). Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 30, 1227–1234.

Page, M. S., & Chang, S. M. (2017). Creating a caregiver program in neuro-oncology. Neuro-Oncology Practice, 4, 116–122.

Perndorfer, C., Soriano, E. C., Siegel, S. D., & Laurenceau, J.-P. (2019). Everyday protective buffering predicts intimacy and fear of cancer recurrence in couples coping with early-stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 28, 317–323.

Powell, C. B., Kneier, A., Chen, L.-M., Rubin, M., Kronewetter, C., & Levine, E. (2008). A randomized study of the effectiveness of a brief psychosocial intervention for women attending a gynecologic cancer clinic. Gynecologic Oncology, 111, 137–143.

Rodin, G., Lo, C., Rydall, A., Shnall, J., Malfitano, C., Chiu, A., Panday, T., Watt, S., An, E., Nissim, R., Li, M., Zimmermann, C., & Hales, S. (2018). Managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM): A randomized controlled trial of a psychological intervention for patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 36, 2422–2432.

Rodin, G., & Zimmermann, C. (2008). Psychoanalytic reflections on mortality: A reconsideration. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 36, 181–196.

Rumpold, T., Schur, S., Amering, M., Kirchheiner, K., Masel, E. K., Watzke, H., & Schrank, B. (2016). Informal caregivers of advanced-stage cancer patients: Every second is at risk for psychiatric morbidity. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24, 1975–1982.

Tie, S., & Poulsen, S. (2013). Emotionally focused couple therapy with couples facing terminal illness. Contemporary Family Therapy, 35, 557–567.

Tranberg, M., Andersson, M., Nilbert, M., & Rasmussen, B. H. (2019). Co-afflicted but invisible: A qualitative study of perceptions among informal caregivers in cancer care. Journal of Health Psychology, 26, 1850–1859.

Treanor, C. J. (2020). Psychosocial support interventions for cancer caregivers: Reducing caregiver burden. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 14, 247–262.

Ugalde, A., Gaskin, C. J., Rankin, N. M., Schofield, P., Boltong, A., Aranda, S., Chambers, S., Krishnasamy, M., & Livingston, P. M. (2019). A systematic review of cancer caregiver interventions: Appraising the potential for implementation of evidence into practice. Psycho-Oncology, 28, 687–701.

Ussher, J. M., & Perz, J. (2010). Gender differences in self-silencing and psychological distress in informal cancer carers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 228–242.

Wertheim, R., Hasson-Ohayon, I., Mashiach-Eizenberg, M., Pizem, N., Shacham-Shmueli, E., & Goldzweig, G. (2018). Hide and “sick”: Self-concealment, shame and distress in the setting of psycho-oncology. Palliative & Supportive Care, 16, 461–469.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first draft of the manuscript was written by RSN and the second author commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors Rinat S. Nissim and Sarah Hales declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

N/A.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to Participate

N/A.

Consent for Publication

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nissim, R.S., Hales, S. Caring for the Family Caregiver: Development of a Caregiver Clinic at a Cancer Hospital as Standard of Care. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 30, 111–118 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-022-09891-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-022-09891-8