Abstract

Several psychotherapeutic interventions are recommended for Eating Disorders (EDs), chiefly individual cognitive-behavioral therapy and family-based treatments. Manualized individual psychodynamic treatments are recommended for adults with Anorexia Nervosa (AN). Evaluation of psychodynamic group treatments in treating EDs requires further assessment, and recent reviews focused only marginally on this topic. To fill this gap, a narrative review through APA PsychInfo, PubMed and Scopus was carried out. Psychodynamic group treatments appear to improve some ED symptoms at the end of the treatment; however, most of the studies cited were not manualized and lacked control groups and follow-ups. The differences in therapeutic methods and the criteria used to measure remission across the studies included, as well as the incorporation of diverse interventions (including psychodynamic group therapy and elements of BT/CBT or psychoeducation), create difficulties when it comes to forming conclusive judgments about the effectiveness of psychodynamic group therapies for Eating Disorders. The need for more rigorous research and Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) is evident.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Epidemiology

Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN) and Binge Eating Disorder (BED) are the eating disorders (EDs) currently described in the DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022). Anorexia Nervosa is a disorder characterized by constant fear of gaining weight, such that individuals with AN enact dysfunctional behaviors that drastically reduce their weight. Two subtypes are described: restrictive (AN-R) or binge-purging (AN-BP). Bulimia Nervosa is characterized by recurrent binging and compensatory behaviors. Binge Eating Disorder is characterized by recurrent binge eating without enacting compensatory behaviors. The prevalence for AN is about 1.4% in females and 0.2% in males; for BN about 1.9% in females and 0.6% in males; and for BED about 2.8% in females and 1.0% in males (Galmiche et al., 2019).

Psychodynamic Perspectives on Eating Disorders

As proposed by Bruch (1982) in her seminal work, Anorexia Nervosa is a disturbance of the self and body image, with difficulties in recognizing internal states (later identified as alexithymia) and a pervasive sense of ineffectiveness. Current psychodynamic perspectives come to similar conclusions, extending them to the broad spectrum of eating disorders. As suggested, people with eating disorders report a fragility of the Self (Amianto et al., 2016) associated with insecure attachment styles (Tasca, 2019) and impairments in reflective functioning (Robinson et al., 2019). In addition, following the PDM-2 (Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual, Lingiardi & McWilliams, 2017) multidimensional model, eating disorders are placed within a continuum of severity, with personality organizations ranging from healthy to neurotic, borderline, and psychotic levels. More specifically, according to the PDM-2, difficulties in emotional regulation, maladaptive perfectionism, hypermentalization and their association with insecure attachment styles could explain the onset and the maintenance of dysfunctional eating disorder behaviors (Mirabella et al., 2023).

Treatment Guidelines for Eating Disorders

International guidelines provided by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2017) recommend as elective treatments for EDs: Eating-Disorder-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT-ED), Family-Based Therapy (FBT), Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA); Focal Psychodynamic Therapy (FPT), the Specialist Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM), and self-help groups. A recent systematic meta-review of meta-analyses and network meta-analyses (Monteleone et al., 2022) evaluated the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic treatments for eating disorders. As the authors reported, in line with NICE guidelines, family treatments were effective for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa in adolescents for the entire course of pathology; cognitive behavioral therapies were superior to other treatments for entire courses of pathology for Bulimia Nervosa and binge eating disorder in adults. Conversely, for Anorexia Nervosa in adults, there were no differences across manualized treatments in terms of effectiveness.

Psychodynamic Therapies for Eating Disorders

As Leichsenring and colleagues (2022) reported, psychodynamic psychotherapies mainly focus on patients’ unconscious conflicts, internalized object relations, and structural impairments. A recent comprehensive review (Abbate-Daga et al., 2016) considered 47 studies in which EDs patients were treated using individual, family, and psychodynamic group psychotherapies. The findings indicated that, overall, psychodynamic treatments impacts positively on eating behaviors and general psychopathology. For individuals with Anorexia Nervosa, their effectiveness is on par with cognitive behavioral therapies and family-based treatments, surpassing Treatments As Usual (TAU) or untreated conditions. However, they are less effective compared to cognitive behavioral therapies for individuals with Bulimia Nervosa. In the case of patients with binge eating disorders, psychodynamic therapies yield superior results when contrasted with psychoeducational therapies or waiting list control groups. They are marginally more effective than cognitive therapies and prove more effective than control or nutritional counseling for individuals with mixed eating disorder diagnoses. However, the authors presented aggregate data on the effectiveness of psychodynamic interventions for eating disorders rather than separate results for each specific therapeutic setting considered in the included studies (e.g., individual or group sessions), and further reviews and meta-analyses are needed to understand the effectiveness of psychodynamic group interventions in particular and to inform future research. In treating eating disorder patients, NICE guidelines recommend Focal Psychodynamic Therapy (Friederich et al., 2019) for people with Anorexia Nervosa, a manualized evidence-based individual treatment of 40–50 sessions that focuses on interpersonal relationships and insight using Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnosis (OPD-2). FPT showed modest efficacy in treating patients with a diagnosis of Anorexia Nervosa, with an increase of BMI (Body Mass Index), supported by a five-year follow-up study (Herzog et al., 2022; Zipfel et al., 2014). Although FPT is the only psychodynamic treatment recommended for EDs, other manualized psychodynamic treatments were developed. Specifically, for Bulimia Nervosa patients, Lunn and Poulsen (2012) proposed a manualized psychoanalytic two-year treatment focused on the transference-countertransference relationship between therapists and patients relying on PDM perspective for case formulation. A Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) (Poulsen at al., 2014) compared this treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy for Bulimia Nervosa. Both treatments led to an improvement of eating symptoms and general eating pathology, but CBT was superior in number of patients free from symptoms after two years. Conversely, Reich and Cierpka (1998) developed a focal psychodynamic treatment for adolescents with Bulimia Nervosa, focusing on bulimic symptoms, transference, defense mechanisms and interpersonal relationships. An RCT (Stefini et al., 2017) compared this treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy. The findings suggested similar results for remission rates from bulimic symptoms for both treatments at the end of the treatment and after a 12-month follow-up. Robinson and colleagues (2019) proposed a modified Mentalization Based Treatment for Eating Disorders patients (MBT-ED). This treatment focused on therapeutic alliance and the improvement of the reflective functioning in EDs, in individual and group sessions. The treatment duration was one year. In a randomized controlled trial (Robinson et al., 2016), this therapy was pitted against Specialist Supportive Clinical Management in individuals with eating disorders who exhibited borderline personality symptoms, with the primary diagnosis being Bulimia Nervosa. The findings reported a decline of eating and borderline personality disorders symptoms in both treatments, even if MBT-ED lead to better improvement in shape and weight concerns. The improvements were supported by follow-ups at 12 and 18 months. However, these results should be taken with caution given the high rate of dropouts in the study and the small sample of patients remitted. Lastly, for individuals with binge eating disorders, Tasca and colleagues (2020) devised an empirically grounded Group Psychodynamic-Interpersonal Psychotherapy (GPIP). This approach was rooted in attachment theory, examining how BED patients employ binge-eating as a coping mechanism to address their anxieties related to rejection and abandonment, serving as a means of self-regulation to manage stress. It lasted only 16 weeks and focused mainly on interpersonal relationships. When examining two randomized controlled trials (Tasca et al., 2006a, 2019) evaluating its efficacy in individuals with binge eating disorders, the earlier study revealed an enhancement in binge-eating episodes and modest alterations in Body Mass Index (BMI), whereas the latter study yielded contradictory outcomes. This treatment and its effect on BED symptoms will be discussed in depth in this review.

Group Therapy for Eating Disorders

The first meta-analysis of group treatments for eating disorders was conducted by Fettes and Peters (1992), considering group education and support, CBT, insight-oriented and eclectic therapies in patients with Bulimia Nervosa. Group psychotherapy showed an effect size of 0.75 in improving bulimic symptoms. Thompson-Brenner and colleagues (2003) conducted a multidimensional meta-analysis comparing group CBT, BT, and eclectic therapies with individual psychotherapies for Bulimia Nervosa patients. Both group-based and individual treatments demonstrated substantial effect sizes in ameliorating binge-purging symptoms. However, when it came to remission rates, individual CBT and BT outperformed group interventions. Conversely, Polnay and coworkers (2014) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs where group CBTs, BTs, IPTs and eclectic therapies were administered for Bulimia Nervosa patients. The results suggest that only group CBT is effective in improving bulimic symptoms compared to control groups with no treatment. Comparisons with individual CBTs could not be tested, given the limited evidence of the studies included.

A more recent meta-analysis (Grenon et al., 2017) analyzed 27 RCTs where group BTs, CBTs, IPTs, Dialectical Behavioral Therapies (DBTs) or GPIPs were administered for patients with eating disorders in general. The results suggested that, in general, group therapy is significantly more effective compared to wait-list treatment conditions. When compared with other active therapies (e.g., individual therapy, drug therapy, self-help, behavioral weight loss), it shows similar results following treatment, after short-term follow-ups (≤ 6 months), and after long-term follow-ups (> 6 months). All forms of group psychotherapy (e.g., psychodynamic or cognitive behavioral therapies) were effective in improving symptoms of eating disorders. As reported above, only one manualized psychodynamic group intervention (i.e., Group Psychodynamic Interpersonal Psychotherapy, Tasca et al., 2020) was developed and tested in a series of RCTs which, at least in part, showed positive effects on BED symptoms. Other psychodynamic group therapies and eclectic group interventions integrating psychodynamic components with CBT/BT, systemic, or psychoeducational components were evaluated for their effectiveness in reducing eating disorder symptoms. The results obtained and their methodological characteristics will be the main focus of this review.

The Present Review

According to the above literature, psychodynamically-oriented interventions (especially FTP) showed a positive effect in reducing the symptoms of eating disorders (especially Anorexia Nervosa). However, conflicting results emerged when different manualized psychodynamic treatments were considered, and some results indicated better efficacy of CBT/BT for specific eating disorder symptoms (e.g., Bulimia Nervosa), highlighting the need for further studies to evaluate the efficacy of specific psychodynamic interventions and different settings (e.g., individual, family, or group sessions) in the treatment of eating disorder symptoms. Interventions involving group sessions, regardless of the theoretical background and therapeutic approach, showed positive effects in the treatment of different forms of eating disorders (Grenon et al., 2017). However, as far as we are aware, no review has collected data specifically on the efficacy of psychodynamic group therapies for eating disorders, and their utility in this context requires further review. Accordingly, the purpose of this review is to analyze the available literature on psychodynamic group treatments for patients with eating disorders, to evaluate results on their effectiveness in decreasing severity of eating symptoms, and to assess the factors of the therapeutic process which contributed to symptomatic remission. The methodological strengths and limitations of the studies reviewed are to be discussed. The results can provide data for clinical purposes and inform future research evaluating psychodynamic group interventions for eating disorders. Establishing conclusions on the effectiveness of group interventions for eating disorders is particularly important given their widespread use in clinical practice (Prestano et al., 2008) and their cost-effectiveness (Rosendahl et al., 2021).

Method

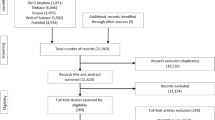

Literature Search

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using the following databases: EBSCO (APA Psychinfo), PubMed, Scopus. Keywords used were: “group therapy” OR “group counseling” OR “group intervention” OR “group treatment” OR “group psychotherap*” OR “group work” OR “group dynamics” OR “group analysis” OR “psychodynamic group” AND anorex* OR “eating disorders” OR bulimi* OR “binge eating” OR “disordered eating” OR “pathological eating”.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included original research papers (1) published in English (2) that assessed the effectiveness of psychodynamic-oriented interventions or eclectic interventions which integrated psychodynamic-oriented approaches with other therapeutic approaches (e.g., CBT/BT or psychoeducational interventions) (3), in treating patients with eating disorders (4) in group sessions, (5), measuring pre- to post-treatment changes in eating disorder symptoms (6). Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Studies that considered psychodynamic group therapy in multimodal setting, reviews, and meta-analysis were also excluded.

Definition of Psychodynamic Psychotherapies

Psychodynamic psychotherapies could be described as an umbrella term for a broad family of psychotherapeutic interventions. As suggested by Leichsenring et al. (2022), we will rely on papers that focused on: a therapeutic relationship; the expression of emotions; defense mechanisms; the link between past and current experiences, recurring themes, interpersonal distress; unconscious conflicts, internalized object relations and how pathology works on a structural level.

Results

Bulimia Nervosa

Psychodynamic Group Therapy

O’Neil & White (1987) assessed the efficacy of a brief psychodynamically-oriented group therapy (duration up to 28 weeks) for 15 college students with Bulimia Nervosa, in a pre-post study which, however, did not included a comparison between control groups. Four patients dropped out (26.7%) and two did not complete the psychometric test (13.3%). Nine patients (60%) improved in all measures of eating pathology, assessed through the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI) and the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT).

Group Analysis

The study of Liedtke and colleagues (1991) compared psychoanalytic post-treatment group therapy (for 27 bulimic patients) with systemic therapy (for 29 bulimic patients) and a waiting-list control group without treatment (11 bulimic patients). The outcomes were assessed at one month after treatment and after three months from the start of the treatment, respectively. Better outcomes were among patients in the psychoanalytic group: 52% patients showed a remission from bulimic symptoms (binges and purging) at follow-up and improving in the EAT dieting and bulimia and food-preoccupation subscales; the EDI ineffectivity and the interoceptive awareness subscales; and in ANIS anancastia (i.e., compulsiveness) subscale, in comparison to the 33% of patients in the systemic group that showed a remission of bulimic pathology and amelioration in EAT bulimia and food-preoccupation subscale and in ANIS compulsiveness scale. Comparisons with a waiting-list control group confirmed these results.

Psychodynamic Group Therapy + BT/CBT Components

Four articles described a psychodynamic group intervention for Bulimia Nervosa patients in combination with cognitive-behavioral (Fernandez & Latimer, 1990; Frommer et al., 1987; Roy-Byrne et al., 1984) or behavioral techniques (Stevens & Salisbury, 1984). All the studies used pre-post designs and did not include control groups. The treatment duration ranged from eight weeks (Fernandez & Latimer, 1990) to one year (Roy-Byrne et al., 1984). Drop-out rates ranged from 0% (Frommer et al., 1987) to 60% (Roy-Byrne et al., 1984). The percentage of subjects in remission, based on several indicators (i.e., decrease of binging, vomiting and purging), goes from 31.6% (Roy-Byrne et al., 1984) to 100% (Frommer et al., 1987). Specifically, in Roy-Byrne et al. (1984), six out of nineteen patients (31.6%) self-reported improved or ceased binges. In this study, three patients were under medication, specifically one taking carbamazepine, and two tranylcypromine instead. In the remaining studies, the authors did not report patients under medications. In Stevens and Salisbury (1984), five out of eight patients (62.5%) self-reported a diminishing of binge-purging episodes after treatment. In Fernandez and Latimer (1990), seventeen patients out of twenty-one (81%) reported positive changes in both binging and purging episodes. Frommer and colleagues (1987) outlined decreases in binging and vomiting, measured by means of dependent correlated t-tests, in their total clinical sample (ninety-two patients). Two studies (Fernandez & Latimer, 1990; Frommer et al., 1987) highlighted that major changes were in the most severe patients in comparison to the milder ones. Two follow-ups, at four months (Fernandez & Latimer, 1990) and one year (Stevens & Salisbury, 1984), reported the persistence of the positive changes observed.

Group Analysis + Cognitive Behavioral and Psychoeducational Components

Valbak (2001) described a long-term group analytic treatment for severe Bulimia Nervosa patients, combining cognitive and psychoeducational elements. The study did not include control groups. Nineteen subjects were assessed. Of these, seven were still in treatment and were excluded from the analysis, and 2 (10.5%) dropped out. The treatment duration ranged from 0.8 to 4.8 years. Of the core ten patients (1 had atypical bulimia), three were on SSRI antidepressants medications. One dropped out (10%), the remaining nine (out nineteen of the total sample, 47.4%) showed a decrease of binge-purging episodes to zero. The absence of bulimic symptoms persisted after six months from the end of the treatment. The calculated effect sizes appeared to be highly significant. A subsequent study (Bøgh et al., 2005) explored the progression and results of a brief integrated group analytic psychotherapy, conducted 2.4–6.1 years (with an average of four years) after its conclusion. The clinical sample included 59 patients. Of these, 16 dropped out (27.1%). The remaining 43 patients had a diagnosis of Bulimia Nervosa (88%) and sub-threshold Bulimia Nervosa (12%). Fourteen (32.5%) were on antidepressants. The results reported that, at follow-up, out of the remaining 43 patients, 58% were remitted or under remission, 14% were classified as Bulimia Nervosa, and 28% met the criteria for an eating disorder not otherwise specified.

Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa

Group Analysis

Prestano et al. (2008) reported a naturalistic study employing a single-case group design to evaluate the process-outcome effectiveness of a long-term group analytic treatment for three patients with restricting Anorexia Nervosa and five patients with Bulimia Nervosa. The study did not include a comparison between control groups. The treatment duration was two years. Two BN patients dropped out of the treatment (25%). Two patients with Anorexia Nervosa (25%) and one with Bulimia Nervosa (12.5%) could be considered recovered from eating disorder symptoms; one Anorexia Nervosa (12.5%) and one Bulimia Nervosa (12.5%) patients did not showed changes in eating pathology; one bulimic subject (12.5%) deteriorated. The group climate presented high degrees of engagement and low levels of avoidance and conflict. Higher levels of therapeutic alliance pre-treatment and engagement led to better improvement of symptoms. However, higher psychological distress pre-treatment was associated with lower levels of therapeutic alliance.

Group Analysis + CBT

In a single-case group study, Koukis (2013) described an outpatient group-analytic treatment combined with cognitive and behavioral components. The single case subjects were Anna, with a diagnosis of severe Anorexia Nervosa and depressive symptoms, and Dimitra, with a diagnosis of Bulimia Nervosa in comorbidity with a borderline personality disorder. Anna took anti-depressants medication. The treatment lasted respectively three and two years. Both patients improved their eating disorder symptoms, but decided to leave the treatment abruptly.

Binge Eating Disorder

Group Analysis

Ciano et al. (2002) conducted a comparison between a group analytic and a psychoeducational group treatment for binge eating disorder patients (6 vs. 5 patients respectively). There were no dropouts. Two patients (33.3%) in the group analytic treatment and one patient (20%) in the psycoeducative one, were using low dose anxiolytics. At the end of the treatment, similar results are reported for the group analytic and the psychoeducational groups: both groups led to a reduction in frequencies of binges, but changes in Body Mass Index (BMI) were not significant. Two follow-ups, at 6 and 12 months, supported these results for both treatments. More specifically, four out of six patients (66.7%) involved in the group analytic treatment were considered remitted, and two (33.3%) were classified as EDNOS. In the psychoeducational group, four out five (80%) patients could be considered without ED, while one deteriorated (20%). At the 12-month follow-up, the group analytic treatment showed better results in comparison to the psychoeducational one in the diminishing of the number of binging episodes per week. In addition, a slightly significant increase in BMI was reported at 12 months for the group-analytical treatment only.

Group Psychodynamic Interpersonal Psychotherapy (GPIP)

Three articles (Tasca et al., 2006a, 2013, 2019) presented group psychodynamic-interpersonal psychotherapies (GPIPs) for patients with a diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED). Of these, two were Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT; Tasca et al., 2006a, 2019) and one was non-randomized (Tasca et al., 2013). Two further articles (Tasca et al., 2006b, 2007) investigated process and outcomes using the sample presented in the study of Tasca and colleague (2006a); eight further articles (Gallagher et al., 2014a, b; Heidinger et al., 2021; Hill et al., 2015; Keating et al., 2014; Maxwell et al., 2012, 2014, 2018) investigated process and outcomes using the sample present in the study of Tasca and colleagues (2013); and one further article (Carlucci et al., 2022) investigated process and outcomes using two samples of Tasca and colleagues (2013, 2019). The treatment duration was 16 weeks. The drop-out percentage ranged from 17.6% (Tasca et al., 2013) to 25.7% (Tasca et al., 2019). Tasca and colleagues also (2006a) reported that higher drop-out rates were in patients with avoidant attachment, compared to patients with anxious attachment.

Of the three main studies (Tasca et al., 2006a, 2013, 2019), the more recent RCT study of Tasca and colleagues (2019) did not demonstrate the effectiveness of the treatment: the group psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy improved the frequency of binge-eating, but in comparison with the results of a control group without treatment, the differences were not significant. Improvements were found regarding abstinence from binges after follow-ups at three and six months, although no differences emerged when comparing this data with the data found in the control group without treatment. More specifically, 28 patients completed follow-ups assessment at six months. Of these, 25% in the GPIP were abstinent, in comparison to 21.4% of the control group.

On the other hand, the two remaining studies (Tasca et al., 2006a, 2013) supported the effectiveness of the intervention in BED patients in the reduction/abstinence from binge episodes, but not in BMI. The results were maintained at six and twelve months.

In the study of Tasca et al. (2006a), 37 participants were assigned to a group psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy, and 37 to a group cognitive behavioral treatment (GCBT). More than half of the participants took antidepressant medication, but comparison analysis did not show an effect on the outcomes. Similar results in outcomes in both group psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapies and group cognitive behavioral treatments are reported, with an improvement (i.e., less than two days without binges in the last week, 78.4% GPIP vs. 73% GCBT at the 12-month follow-up) or abstinence (i.e., no binge days in the last week, 56.8% GPIP vs. 67.7% GCBT at the 12-month follow-up) from binge eating symptoms. In addition, findings identified greater effectiveness of group psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapies in comparison to waiting-list control groups. Furthermore, comparing group psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapies and group cognitive behavioral therapies, the authors found better outcomes in GPIPs for patients with anxious attachments, while in GCBTs for patients with avoidant attachments (Tasca et al., 2006a). According to a follow-up study (Tasca et al., 2007), both treatments showed changes in attachment style, which however was not related to the reduction of the eating symptomatology.

In the study of Tasca and colleagues (2013), the participants were divided into two homogeneous groups, one with low attachment anxiety and one with high attachment anxiety. In a total sample of 102 patients, 18 dropped out (17.6%). The remaining patients in GPIP lost 10% weight (11.4% low attachment anxiety group vs. 6% high attachment anxiety group at the 12-month follow-up), improved (59.6% low vs. 56% high in the past seven days; 63.5% low vs. 64% high in past 28 days at the 12-month follow-up) or were abstinent (42.3% low vs. 44% high in past 7 days; 25% low vs. 30% high in the past 28 days at the 12-month follow-up) from binge eating symptoms. At the beginning of the treatment, therapists showed greater levels of complementarity with the patients with low anxious attachment styles, which was positively associated with the reduction in frequency of binge-eating post-treatment in both groups in Maxwell et al.’s study (2012). Two follow-up studies showed that the treatment implemented by Tasca et al. (2013) changed attachment insecurity on the individual (Maxwell et al., 2014) and group (Keating et al., 2014) level. However, these changes were not associated with the reduction of binge-eating frequency. Hill and colleagues (2015) specified that, in both groups, there was an improvement in the Overall Defense Functioning (ODF), which mediated the decrease of binge-eating episodes after treatment. Conversely, the study of Carlucci et al. (2022) reported that the ODF group was not associated with a reduction in binge-eating episodes. Maxwell and colleagues (2018) highlighted that higher levels of reflective functioning pre-treatment predicted positive outcomes in eating symptoms, while pre-treatment levels of Coherence of Mind did not seem to influence treatment effectiveness. Nevertheless, group psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy seems to improve both reflective functioning and coherence of mind. Finally, the comparison with a non-clinical control group showed that genotypes x times interaction effects were not associated to the reduction of the post-treatment of the binge-eating episodes (Heidinger et al., 2021).

Concerning the procedural elements at play, in Tasca et al. investigation (2006a), the group atmosphere exhibited an increasing linear growth within the cognitive behavioral group therapies, whereas it displayed greater variability in group psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapies. In this latter intervention, the increase in group engagement (i.e., the degree of cohesion with the group) contributed to positive outcomes in anxious patients (Tasca et al., 2006b). Furthermore, repairing the ruptures in the therapeutic alliance within GPIP, particularly in cases of low engagement, led to its enhancement (Tasca et al., 2006b). In the study of Tasca and colleagues (2013), the therapeutic alliance exponentially increased and was positively correlated with outcomes in both groups (high vs. low anxious attachment), especially among patients with higher levels of attachment anxiety. In Gallagher and colleagues (2014a), group cohesion similarly grows exponentially in both groups. Nonetheless, this outcome was associated with a decrease in the frequency of binge-eating episodes solely within the high-anxiety group, despite these patients exhibiting a lower sense of group cohesion when compared to the low-anxiety group (Gallagher et al., 2014b).

Patients with Mixed Diagnoses

Psychodynamic Group Therapy

Two studies (Fontao & Mergenthaler, 2008; Moreno, 1998) assessed the efficacy of psychodynamic group therapy in reducing symptoms among patients with various eating disorder diagnoses through a pre-post design, lacking a comparison with control groups. Treatment duration was one year in Fontao and Mergenthaler (2008), and 3 years in Moreno (1998). Drop-out rates ranged from 33.3% (Moreno, 1998) to 37.5% (Fontao & Mergenthaler, 2008). Moreno (1998) reported a long-term psychodynamic group treatment for 15 patients with Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and obesity. The intervention led to the complete remission of only three patients (20%); five dropped out early (33.3%); and the remaining 7 (46.7%) maintained dysfunctional eating disorder behaviors at termination. Therapeutic factors such as self-awareness, universality, relationships with others, and emotionally-laden feedback were associated with remission symptoms. Fontao and Margentaler (2008) conducted outpatient psychodynamic group therapy for eight females with Bulimia Nervosa, binge eating disorder, and eating disorder non otherwise specified (EDNOS). At the end of the treatment, only three patients (37.5%) showed an improvement in eating behaviors and attitudes toward food. Therapeutic factors that led to changes in eating pathology were catharsis, interpersonal learning-output, and self-disclosure.

Psychodynamic Group Therapy + CBT

Iancu and coworkers (2006) reported a short-term cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic group treatment for 30 male and female soldiers with a diagnosis of AN, BN, or EDNOS. The study used a pre-post experimental design and did not include a comparison between control groups. The treatment lasted six months. Four patients were under medication (i.e., paroxetine). Six women dropped out (20%). Twenty-four out of thirty patients (80%) showed a significant improvement of EAT-26 and EDI-2 scores at treatment termination, but not in alexithymia and dissociative traits.

Discussion

The current narrative review aimed at summarizing studies that considered psychodynamic group treatments for patients with an eating disorder diagnosis in order to highlight the possible applicability of the psychodynamic group device in this clinical population. A total of twenty-seven studies were included. Of these, eight studies considered groups of Bulimia Nervosa patients only; two studies considered groups of patients with Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa; 14 studies considered groups of patients with binge-eating disorders only; three studies considered groups of patients with mixed diagnoses. The articles included seem to suggest some positive effects particularly among patients with Bulimia Nervosa and binge eating disorder, while less promising and more conflicting findings emerged regarding groups including Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa patients together and groups with mixed diagnosis patients. This could suggest a reduced effectiveness of these interventions when patients with different symptoms are included within the same group. More specifically, for Bulimia Nervosa patients, preliminary data seem to highlight an improvement in binging and purging behaviors (ranging from 31.6 to 100%). These results are supported for psychodynamic group therapies, group analysis, and eclectic treatments integrating psychodynamic interventions with BT/CBT components or BT/CBT and psychoeducational components.

Conflicting results emerged considering groups including Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa patients mixed together. Koukis (2013) reported an improvement in AN and BN patients involved, the study was limited by the assessment of only two patients who, what’s more, dropped out abruptly. In the study by Prestano and colleagues (2008) the remission rate was relatively small (37.5%) and future studies are needed to deepen these preliminary findings.

For binge eating disorder patients, the results which emerged seem to suggest some positive effect of psychodynamic group interventions in reducing binging episodes (ranging from 25 to 78.4%). However, changes in body mass index are not significant in the studies included. More specifically, group analysis and GPIP were assessed for their effectiveness for binge eating disorder patients. While the former seems to show moderate effectiveness with 66.7% of patients in remission in one study (Ciano et al., 2002), conflicting results emerged regarding GPIP. Three studies were conducted to assess its effectiveness; of these, two were RCT.

The initial randomized controlled trial (RCT) presented promising outcomes (with 78.4% of patients showing improvement and 56.8% achieving abstinence; Tasca et al., 2006a) and these findings were further corroborated in a subsequent study utilizing a pre-post design (indicating an improvement from 56% in the past 7 days to 64% in the past 28 days, and an increase from 25% in the past 28 days to 44% in the past 7 days of patients achieving abstinence; Tasca et al., 2013). However, a more recent RCT reported less favorable results, indicating a lower percentage of patients achieving abstinence from binge eating (with only 25% of patients attaining abstinence; Tasca et al., 2019). Accordingly, further studies are needed to establish clearer conclusions on GPIP effectiveness in patients with binge eating disorders.

In patients with mixed diagnoses, psychodynamic group treatments seem to show an improvement in dysfunctional eating behaviors (from 20 to 80%), although the remission rate is relatively small for pure psychodynamic treatments (range from 20 to 37.5%) in comparison with a treatment that combined psychodynamic and CBT components (80% of patients in remission). These preliminary findings seem to suggest the greater effectiveness of eclectic interventions for these patients, although further studies are needed to establish firm conclusions.

Specifically considering the treatment of Anorexia Nervosa, only a small number of patients (from 0% (Koukis, 2013) to 26.7% (Iancu et al., 2006) patients) obtained benefits from psychodynamic group therapies. However, it should be specified that Anorexia Nervosa patients were enrolled in groups with mixed diagnoses (AN, BN, BED, EDNOS). It is possible that the group composition influenced the outcomes in patients with Anorexia Nervosa; however, in a mixed group with both AN and BN patients, the study by Prestano et al. (2008) reported better outcomes among AN patients in comparison with BN patients. Another explanation can be the high treatment resistance (Abbate-Daga et al., 2013) and low therapeutic alliance (Lingiardi & Muzi, 2019) of Anorexia Nervosa patients, which can negatively affect therapeutic outcomes (Zipfel et al., 2014). As reported by Tasca and colleagues (2006b), focusing on the alliance rupture and reparations in psychodynamic group therapies can promote a higher degree of engagement. The main role of engagement seems supported by the study of Prestano and colleagues (2008), which highlighted high levels of engagement and therapeutic alliance in patients who benefited from the treatment (both AN and BN) as well as low levels of pre-treatment therapeutic alliance in BN patients who dropped out. Another possible factor that may have affected the outcomes is how the group climate has been perceived. The climate in groups of eating disorders patients can be connotated by high engagement and high avoidance. The ambivalence of the group climate can be related to poorly integrated object relations, re-enacted in the group context (Margherita et al., 2021).

Process factors that were mainly found as contributors for psychodynamic group therapy effectiveness were: group cohesion, group climate, therapeutic alliance, and its rupture and reparation. This is in line with recent developments in group psychotherapy research (Rosendahl et al., 2021), stating that group cohesion and alliance are the main variables that could influence therapy outcomes. However, only a handful of studies (eight out 27) considered process variables involved in symptoms remission; therefore, other studies are needed.

Although the results which emerged are at least partially promising, particularly for patients with Bulimia Nervosa and binge eating disorder, most of the articles included in the current review are dated and showed several methodological limitations that need to be considered in future studies. More specifically, only two studies were RCT, and few research included control groups or a comparison between different interventions, which can limit the methodological rigor of the conclusions drawn. In addition, many different treatments (e.g., psychodynamic group therapies, group analysis, GPIP, eclectic) were assessed for their effectiveness in treating eating disorder symptoms, and only one of them, the GPIP, was a manualized treatment. Lack of manualized interventions limit the replicability and generalizability of the interventions assessed; thus, further efforts should be made in this direction. Moreover, only a handful of interventions exclusively used a psychodynamic approach, while other eclectic interventions integrated a psychodynamic component with BT/CBT or psychoeducational components. Studies that assessed the effectiveness of eclectic interventions; however, they did not provide data on the therapeutic factors which led to an improvement of the symptoms and did not clarify if psychodynamic group techniques per se are effective or not in treating eating disorder symptoms. Furthermore, different indicators of symptom remission were considered across the studies, making it more difficult to compare results and draw firm conclusions on the effectiveness of psychodynamic group interventions. In addition, some studies reported patients that were under medication, while others did not provide this information. Similarly, no study gave any indication of the use of nutritional therapies in the included patients. The pharmacological administration as well as the recurrence to nutritional therapy could have affected the outcomes identified. Only the study of Tasca and colleagues (2006a) controlled the effect of pharmacological administration, finding, however, no effect of medication intake on the outcome of therapy. Considering medications and nutritional therapies administration in future studies and controlling their effect on therapeutic outcomes is necessary. Additional methodological constraints encompass: the lack of follow-up assessments and effect size measurements in certain studies, thereby hindering the ability to substantiate post-treatment improvements; insufficient methodological descriptions and the utilization of non-validated measures or self-reported data for evaluating changes in eating disorder symptoms in older studies, rendering replication of interventions and validation of the assessed group treatment’s efficacy challenging; small sample sizes, primarily consisting of women, potentially impeding the generalizability of the identified outcomes.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current narrative review has the main limitation that it is not a meta-analysis, which resulted in an absence of statistical and quantitative data. No articles published in languages other than English or taken from alternative sources than the main psychological scientific databases were included in the present review. Furthermore, we reported the effect of psychodynamic group therapies addressing eating disorder symptoms only, with no considerations of their effect on symptoms often found in comorbidity such as anxiety, depression, substance use, and post-traumatic stress disorders (Hambleton et al., 2022). The data which emerged from the current review should be taken with caution, given the presence of several methodological limitations of the articles reviewed. Furthermore, the different psychodynamic group treatments implemented and the remission indicators taken into account make it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the effectiveness of psychodynamic group treatments from eating disorder patients.

However, these limitations can stimulate future directions for research in this field. First, more methodologically rigorous studies are needed. In particular, conducting RCT and including control groups and/or treatments comparison can further support and expand the results highlighted here. In addition, future studies should evaluate eating disorder symptoms using validated and reliable measures. Male populations affected by eating disorders were poorly explored, although this can be mainly due to the higher prevalence of eating disorders among women. Similarly, no study reported the sexual orientation of patients, although recent data shown that about 54% of LGBT teens received, in their lifetime, an ED diagnosis (The Trevor Project et al., 2018). Future studies should therefore consider both the male population as well as sexual and gender minorities. Furthermore, studies that considered therapeutic process factors are limited as well. Future studies are necessary to deepen our understanding of mechanisms leading to symptomatologic remission. In particular, group alliance rupture and reparation deserves more attention according to research trends in recent years (Tasca & Marmarosh, 2023). Focusing on these processes can be effective in diminishing the high drop-out rates, as highlighted by Tasca and colleagues (2006b) in this review. Following the results of the current narrative review, clinical trials on psychodynamic groups which only include Anorexia Nervosa patients are needed, given the lack of studies in this regard. Finally, further manualized treatment should be developed in order to guarantee replicability of interventions and research as well as more methodological rigor.

Conclusions

This narrative review identified some positive effects of psychodynamic group therapy in eating disorders symptoms, particularly in groups of patients with Bulimia Nervosa and binge eating disorders. However, these results should be taken with caution considering the methodological limitations of the studies included. Accordingly, more rigorous studies are needed, especially through the development of manualized treatments assessed in RCT. Nonetheless, the findings which emerge in this systematic review can serve as a stimulus for future research, in order to fill the current literature gap through the adoption of an evidence-based approach which can further substantiate the actual usefulness of psychodynamic group therapy for eating disorders. Considering the potential cost-effective efficiency of group therapy, this takes on additional clinical value.

References

Abbate-Daga, G., Amianto, F., Delsedime, N., De-Bacco, C., & Fassino, S. (2013). Resistance to treatment and change in Anorexia Nervosa: A clinical overview. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-294.

Abbate-Daga, G., Marzola, E., Amianto, F., & Fassino, S. (2016). A comprehensive review of psychodynamic treatments for eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 21(4), 553–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0265-9.

American Psychiatric Association. (APA). (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Association.

Amianto, F., Northoff, G., Abbate Daga, G., Fassino, S., & Tasca, G. A. (2016). Is Anorexia Nervosa a disorder of the self? A psychological approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 849. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00849.

Bøgh, E. H., Rokkedal, K., & Valbak, K. (2005). A 4-year follow‐up on bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review: The Professional Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 13(1), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.601.

Bruch, H. (1982). Anorexia Nervosa: Therapy and theory. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 139(12), 1531–1538. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.139.12.1531.

Carlucci, S., Chyurlia, L., Presniak, M., Mcquaid, N., Wiley, J. C., Wiebe, S., & Tasca, G. A. (2022). A group’s level of defensive functioning affects individual outcomes in group psychodynamic-interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 59(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000423.

Ciano, R., Rocco, P. L., Angarano, A., Biasin, E., & Balestrieri, M. (2002). Group-analytic and psychoeducational therapies for binge-eating disorder: An exploratory study of efficacy and persistence of effects. Psychotherapy Research : Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 12(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/713664282.

Fernandez, D., & Latimer, P. (1990). A group treatment program for bulimia nervosa. Group, 14(4), 241–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01459560.

Fettes, P. A., & Peters, J. M. (1992). A meta-analysis of group treatments for bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199203)11:2<97::AID-EAT2260110202>3.0.CO;2-H.

Fontao, M. I., & Mergenthaler, E. (2008). Therapeutic factors and language patterns in group therapy application of computer-assisted text analysis to the examination of microprocesses in group therapy: Preliminary findings. Psychotherapy Research, 18(3), 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300701576352.

Friederich, H. C., Wild, B., Zipfel, S., Schauenburg, H., & Herzog, W. (2019). Anorexia Nervosa: Focal Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Hogrefe.

Frommer, M. S., Ames, J. R., Gibson, J. W., & Davis, W. N. (1987). Patterns of symptom change in the short-term group treatment of bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(4), 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<469::AID-EAT2260060403>3.0.CO;2-W.

Gallagher, M. E., Tasca, G. A., Ritchie, K., Balfour, L., & Bissada, H. (2014a). Attachment anxiety moderates the relationship between growth in group cohesion and treatment outcomes in group psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy for women with binge eating disorder. Group Dynamics: Theory Research and Practice, 18, 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034760.

Gallagher, M. E., Tasca, G. A., Ritchie, K., Balfour, L., Maxwell, H., & Bissada, H. (2014b). Interpersonal learning is associated with improved self-esteem in group psychotherapy for women with binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy (Chic), 51, 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031098.

Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G., & Tavolacci, M. P. (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy342.

Grenon, R., Schwartze, D., Hammond, N., Ivanova, I., Mcquaid, N., Proulx, G., & Tasca, G. A. (2017). Group psychotherapy for eating disorders: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(9), 997–1013. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22744.

Hambleton, A., Pepin, G., Le, A., Maloney, D., Touyz, S., & Maguire, S. (2022). Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of eating disorders: Findings from a rapid review of the literature. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00654-2.

Heidinger, B. A., Cameron, J. D., Vaillancourt, R., De Lisio, M., Ngu, M., Tasca, G. A., & Goldfield, G. S. (2021). No association between dopaminergic polymorphisms and response to treatment of binge-eating disorder. Gene, 781, 145538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2021.145538.

Herzog, W., Wild, B., Giel, K. E., Junne, F., Friederich, H. C., Resmark, G., & Zipfel, S. (2022). Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimized treatment as usual in female outpatients with Anorexia Nervosa (ANTOP study): 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial in Germany. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(4), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00028-1.

Hill, R., Tasca, G. A., Presniak, M., Francis, K., Palardy, M., Grenon, R., & Bissada, H. (2015). Changes in defense mechanism functioning during group therapy for binge-eating disorder. Psychiatry, 78(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2015.1015897.

Iancu, I., Cohen, E., Yehuda, Y. B., & Kotler, M. (2006). Treatment of eating disorders improves eating symptoms but not alexithymia and dissociation proneness. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 47(3), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.01.001.

Keating, L., Tasca, G. A., Gick, M., Ritchie, K., Balfour, L., & Bissada, H. (2014). Change in attachment to the therapy group generalizes to change in individual attachment among women with binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy (Chic), 51, 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031099.

Koukis, A. (2013). Group analysis and eating disorders: A study of the therapeutic impact of group-analytic psychotherapy on women suffering from Anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Group Analysis, 46(2), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0533316413488706l.

Leichsenring, F., Abbass, A., Heim, N., Keefe, J. R., Luyten, P., Rabung, S., & Steinert, C. (2022). Empirically supported psychodynamic psychotherapy for common mental disorders–An update applying revised criteria: Systematic review protocol. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 976885. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.976885.

Liedtke, R., Jäger, B., Lempa, W., Künsebeck, H. W., Gröne, M., & Freyberger, H. (1991). Therapy outcome of two treatment models for bulimia nervosa: Preliminary results of a controlled study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 56(1–2), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288531.

Lingiardi, V., & McWilliams, N. (Eds.). (2017). Psychodynamic diagnostic manual. Second Edition. PDM-2. The Guilford Press.

Lingiardi, V., & Muzi, L. (2019). Esiti del trattamento. In M. Recalcati, & M. A. Rugo (Eds.), Alimentare Il Desiderio. Il Trattamento Istituzionale dei disturbi alimentari. Raffaello Cortina.

Lunn, S., & Poulsen, S. (2012). Psychoanalytic psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa: A manualized approach. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 26(1), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2011.652977.

Margherita, G., Gargiulo, A., Gaudioso, R., & Esposito, G. (2021). Treating eating disorders in groups: A pilot study on the role of a structured intervention on perfectionism on group climate. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12448.

Maxwell, H., Tasca, G. A., Gick, M., Ritchie, K., Balfour, L., & Bissada, H. (2012). The impact of attachment anxiety on interpersonal complementarity in early group therapy interactions among women with binge eating disorder. Group Dynamics, 16(4), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029464.

Maxwell, H., Tasca, G. A., Ritchie, K., Balfour, L., & Bissada, H. (2014). Change in attachment insecurity is related to improved outcomes 1-year post group therapy in women with binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy (Chic), 51, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031100.

Maxwell, H., Tasca, G. A., Grenon, R., Faye, M., Ritchie, K., Bissada, H., & Balfour, L. (2018). Change in attachment dimensions in women with binge-eating disorder following group psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 28(6), 887–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1278804.

Mirabella, M., Muzi, L., Franco, A., Urgese, A., Rugo, M. A., Mazzeschi, C., & Lingiardi, V. (2023). From symptoms to subjective and bodily experiences: The contribution of the psychodynamic diagnostic manual (PDM-2) to diagnosis and treatment monitoring in eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia Bulimia and Obesity, 28(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-023-01562-3.

Monteleone, A. M., Pellegrino, F., Croatto, G., Carfagno, M., Hilbert, A., Treasure, J., & Solmi, M. (2022). Treatment of eating disorders: A systematic meta-review of meta-analyses and network meta-analyses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104857.

Moreno, J. K. (1998). Long-term psychodynamic group psychotherapy for eating disorders: A descriptive case report. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 23(3), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933929808411400.

National Institute of Clinical Excellence. (NICE). (2017). Eating disorders: Recognition and treatment. Author.

O’Neil, M. K., & White, P. (1987). Psychodynamic group treatment of young adult bulimic women: Preliminary positive results. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 32(2), 153–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674378703200215.

Polnay, A., James, V. A. W., Hodges, L., Murray, G. D., Munro, C., & Lawrie, S. M. (2014). Group therapy for people with bulimia nervosa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 44(11), 2241–2254. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002791.

Poulsen, S., Lunn, S., Daniel, S. I., Folke, S., Mathiesen, B. B., Katznelson, H., & Fairburn, C. G. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(1), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121511.

Prestano, C., Lo Coco, G., Gullo, S., & Lo Verso, G. (2008). Group analytic therapy for eating disorders: Preliminary results in a single-group study. European Eating Disorders Review: The Professional Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 16(4), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.871.

Reich, G., & Cierpka, M. (1998). Identity conflicts in bulimia nervosa: Psychodynamic patterns and psychoanalytic treatment. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 18(3), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351699809534199.

Robinson, P., Hellier, J., Barrett, B., Barzdaitiene, D., Bateman, A., Bogaardt, A., & Fonagy, P. (2016). The NOURISHED randomised controlled trial comparing mentalisation-based treatment for eating disorders (MBT-ED) with specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM-ED) for patients with eating disorders and symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Trials, 17, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1606-8.

Robinson, P., Skårderud, F., & Sommerfeldt, B. (2019). Hunger. Mentalization-based treatments for eating disorders. Springer.

Rosendahl, J., Alldredge, C. T., Burlingame, G. M., & Strauss, B. (2021). Recent developments in group psychotherapy research. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 74(2), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.20200031.

Roy-Byrne, P., Lee‐Benner, K., & Yager, J. (1984). Group therapy for bulimia. A year’s experience. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 3(2), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198424)3:2<97::AID-EAT2260030209>3.0.CO;2-I.

Stefini, A., Salzer, S., Reich, G., Horn, H., Winkelmann, K., Bents, H., & Kronmüller, K. T. (2017). Cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic therapy in female adolescents with bulimia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(4), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.01.019.

Stevens, E. V., & Salisbury, J. D. (1984). Group therapy for bulimic adults. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 54(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1984.tb01483.x.

Tasca, G. A. (2019). Attachment and eating disorders: A research update. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.03.003.

Tasca, G. A., & Marmarosh, C. (2023). Alliance rupture and repair in group psychotherapy In C. F. Eubanks, L. W. Samstag, & J. C. Muran (Eds.), Rupture and repair in psychotherapy: A critical process for change (pp. 53–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000306-003.

Tasca, G. A., Ritchie, K., Conrad, G., Balfour, L., Gayton, J., Daigle, V., & Bissada, H. (2006a). Attachment scales predict outcome in a randomized controlled trial of two group therapies for binge eating disorder: An aptitude by treatment interaction. Psychotherapy Research, 16, 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300500090928.

Tasca, G. A., Balfour, J., Ritchie, K., & Bissada, H. (2006b). Developmental changes in group climate in two types of group therapy for binge-eating disorder: A growth curve analysis. Psychotherapy Research : Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 16(4), 499–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600593359.

Tasca, G. A., Balfour, L., Ritchie, K., & Bissada, H. (2007). Change in attachment anxiety is associated with improved depression among women with binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy (Chic), 44, 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.44.4.423.

Tasca, G. A., Ritchie, K., Demidenko, N., Balfour, L., Krysanski, V., Weekes, K., & Bissada, H. (2013). Matching women with binge eating disorder to group treatment based on attachment anxiety: Outcomes and moderating effects. Psychotherapy Research, 23(3), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.717309.

Tasca, G. A., Koszycki, D., Brugnera, A., Chyurlia, L., Hammond, N., Francis, K., & Balfour, L. (2019). Testing a stepped care model for binge-eating disorder: A two-step randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 49(4), 598–606. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718001277.

Tasca, G. A., Mikail, S., & Hewitt, P. (2020). Group psychodynamic-interpersonal psychotherapy: An evidence-based Transdiagnostic Approach. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000213-000.

The Trevor Project, National Eating Disorders Association, & Reasons Eating Disorder Center (2018). Eating Disorders Among LGBTQ Youth: A 2018 National Assessment Retrieved from: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/blog/eating-disorders-among-lgbtq-youth.

Thompson-Brenner, H., Glass, S., & Westen, D. (2003). A multidimensional meta‐analysis of psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(3), 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg024.

Valbak, K. (2001). Good outcome for bulimic patients in long-term group analysis: A single-group study. European Eating Disorders Review: The Professional Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 9(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.369.

Zipfel, S., Wild, B., Groß, G., Friederich, H. C., Teufel, M., Schellberg, D., & Herzog, W. (2014). Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with Anorexia Nervosa (ANTOP study): Randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 383(9912), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61746-8.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Creation of the frame used in this review: TT, DB, GAB, and LR. Research and selection of the articles discussed in the review and data extraction: DB, MNP, FS. Interpretation of the results: TT, DB, MNP, FS, GAB, and LR. Supervision of the entire work: TT, GAB, LR. All authors were involved in the discussion, writing, and revision of the manuscript and they gave their final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Trombetta, T., Bottaro, D., Paradiso, M.N. et al. Psychodynamic Group Therapy for Eating Disorders: A Narrative Review. J Contemp Psychother (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-023-09614-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-023-09614-6