Abstract

Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has been used to evaluate regional cerebral tissue oxygen saturation (ScO2) during the last decades. Perioperative management algorithms advocate to maintain ScO2, by maintaining or increasing cardiac output (CO), e.g. with fluid infusion. We hypothesized that ScO2 would increase in responders to a standardized fluid challenge (FC) and that the relative changes in CO and ScO2 would correlate. This study is a retrospective substudy of the FLuid Responsiveness Prediction Using Extra Systoles (FLEX) trial. In the FLEX trial, patients were administered two standardized FCs (5 mL/kg ideal body weight each) during cardiac surgery. NIRS monitoring was used during the intraoperative period and CO was monitored continuously. Patients were considered responders if stroke volume increased more than 10% following FC. Datasets from 29 non-responders and 27 responders to FC were available for analysis. Relative changes of ScO2 did not change significantly in non-responders (mean difference − 0.3% ± 2.3%, p = 0.534) or in fluid responders (mean difference 1.6% ± 4.6%, p = 0.088). Relative changes in CO and ScO2 correlated significantly, p = 0.027. Increasing CO by fluid did not change cerebral oxygenation. Despite this, relative changes in CO correlated to relative changes in ScO2. However, the clinical impact of the present observations is unclear, and the results must be interpreted with caution.

Trial registration:http://ClinicalTrial.gov identifier for main study (FLuid Responsiveness Prediction Using Extra Systoles—FLEX): NCT03002129.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the last decades, near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) monitoring has gained interest as a tool to monitor cerebral oxygenation and perfusion during cardiac surgery in an attempt to minimize cerebral complications [1,2,3,4]. NIRS works by measuring cerebral tissue oxygen saturation (ScO2) and reflects an approximately 25/75 arterial/venous saturation ratio, depending on the device used [5, 6]. Numerous intervention algorithms to mitigate and reverse cerebral desaturation have been published, of which the one published in 2007 appears widely adopted [7]. Application of this hierarchical algorithm has lowered the time with cerebral desaturation measured by NIRS [8,9,10,11]. However, it is not clear which part(s) of the algorithm is the successful one to convert an ongoing desaturation. Part of the intervention algorithm is to increase cardiac output (CO) if cerebral desaturation occurs as indicated by decreased ScO2. However, this intervention per se has been tested primarily in non-cardiac surgery with diverging findings [12,13,14,15].

The aim of this study was to elucidate the difference in ScO2 after versus before a standardized 5 mL/kg ideal body weight fluid challenge (FC). Furthermore, we studied the association between relative changes in ScO2 and CO during a standardized FC in hemodynamic responders and non-responders to a FC in adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Responders were defined as patients with an increase in stroke volume, SV > 10% following FC.

We hypothesized that in responders ScO2 would increase, as opposed to non-responders. Furthermore, we hypothesized that relative changes of CO and ScO2 would correlate.

2 Methods

2.1 Study setting

This study is a retrospective substudy of the FLuid Responsiveness Prediction Using Extra Systoles (FLEX) trial [16]. The trial was conducted at the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), The Netherlands between January 2017 and June 2017. The FLEX study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (METc UMCG number 2016.449, ABR number NL58966.042.16) and registered at http://ClinicalTrial.gov (NCT03002129).

2.2 Participants

All participants in the FLEX trial were older than 18 years of age and scheduled for elective coronary artery bypass grafting with no additional procedures, with or without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Exclusion criteria were preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction < 35%, kidney function requiring haemodialysis, and heart rhythm disturbances such as atrial fibrillation or frequent extra systoles. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients included.

2.3 Study protocol

The study protocol and the primary results from the FLEX trial have been previously published [16]. In short, all patients received a standardized FC (5 mL/kg ideal body weight of lactated Ringer; Baxter, Utrecht, The Netherlands) at two time points during surgery. FC1: after induction of anaesthesia and placement of the central venous catheter and before surgical incision. FC2: during preparation of the left internal mammarian artery. Changes to all other infusion rates as well as vasoactive interventions were avoided during the infusion periods, which were approximately 5 min.

2.4 Data acquisition

2.4.1 Cerebral oximetry

NIRS monitoring was obtained with self-adhesive sensors (Medtronic/Covidien INVOS Cerebral/Somatic Oximetry Adult Sensors—Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA) placed bilaterally on the patient’s forehead before induction of anaesthesia. The sensors were connected to a Covidien/Medtronic INVOS 5100c Cerebral/Somatic Oximeter monitor (Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA). Data was recorded in the electronic hospital patient data management system developed to sample data during cardiac surgery (CAROLA, RIVM Centrum Extreme Veiligheid, Bilthoven, The Netherlands) with ScO2 baseline marked before anaesthesia related preoxygenation and sampled every 30 s and no in-unit data storage was used. Data was exported to Excel format after surgery.

All variables analysed were mean values of left and right channel. In case a patient had only unilateral NIRS readings one channel was used for analysis.

2.4.2 Hemodynamic measurements and alignment to the NIRS readings

All patients were equipped with FloTrac sensors, which were connected to the EV1000 hemodynamic monitor (both Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, USA) for continuous measurement of SV, CO, and mean arterial pressure (MAP). The EV1000 monitor sampled data every 20 s and all data was later exported to Excel format. FC was marked in the monitor system. MAP was also recorded by the CAROLA system and therefore MAP time series were used to align data for CO from the EV1000 monitor and ScO2 values from the CAROLA system. All values were analysed from the last registered value before FC start and then for the following period of the FC in 1-min intervals. Last extracted value was the first value registered after FC was ended.

Not all patients had complete NIRS readings and hemodynamic data, since the use of NIRS was dependent on the preference of the anaesthetist. To maximize the output from the available data FC1 and FC2 were pooled for analysis.

Haematocrit levels from arterial blood gasses were extracted from the CAROLA system as the first and last value accessible in the procedure.

2.5 Outcome

2.5.1 Regional cerebral oximetry

The primary outcome was to evaluate relative changes in ScO2 during two FCs. Furthermore, the absolute difference in ScO2 was evaluated for each individual as well as the correlation of ScO2 and CO.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

All analyses were conducted for the whole sample of datasets and subsequently stratified for non-responders and fluid responders, except for correlation analysis which was conducted for the whole sample only.

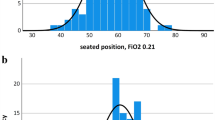

The normality of data distribution was evaluated by visual inspection of quantile–quantile plots. Normally distributed data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), otherwise as median and interquartile range (IQR). Normally distributed data were compared with paired sample t test for difference between different time points. Student’s t-test was used to test for difference between groups. Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages and compared with Pearson’s Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was assessed at the 5% level.

Correlation was tested with the Pearson correlation coefficient.

No sample size calculation was performed since this study was a secondary analysis of an already finished trial. Statistical power is expressed through the reported confidence intervals.

3 Results

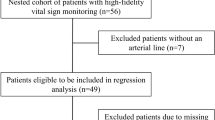

Sixty-one patients were included in the FLEX study. Twenty-seven patients had complete sets of hemodynamic data and NIRS data at FC1. At FC2, 29 patients had complete datasets. In total, this allowed analysis of 56 complete datasets comprising 29 non-responders and 27 fluid responders datasets from 31 unique patients.

Preoperative characteristics, medication, comorbidity and intraoperative data are presented in Table 1 for patients with complete datasets at both FC1 and FC2 (n = 25). Tables 1A and 1B (Appendix S1) illustrate that there was no difference in any of the pre-operative variables for non-responders vs. fluid responders at either FC1 or FC2.

Table 2 illustrates the difference in absolute values and relative changes for CO and ScO2 before and after FC. In general, CO and MAP increased significantly for both non-responders and responders. CO before FC for fluid responders were markedly lower than the corresponding CO for non-responders (3.3 ± 0.8 L/min vs. 4.5 ± 1.4 L/min, p < 0.001).

The differences in relative changes in ScO2 for fluid responders (mean difference 1.6% and 95% CI − 0.3; 3.4, p = 0.088) and non-responders (mean difference − 0.3% and 95% CI − 1.2; 0.6, p = 0.534) was not significant. The ScO2 difference in absolute values before and after FC was not significant for either fluid responders (66 ± 7% vs. 67 ± 6%, p = 0.084) or non-responders (66 ± 6% vs. 66 ± 7%, p = 0.555).

CO and ScO2 obtained at the end of FC as relative change to the value before FC are plotted in Fig. 1 and the correlation coefficient was 0.295, p = 0.027. In Fig. 2 (fluid non-responders) and Fig. 3 (fluid responders) the relative changes minute by minute during the FC are presented, showing that the correlations are driven by the fluid responders.

4 Discussion

The main finding of the present study was that the ScO2 did not change for both responders and non-responders of a FC during cardiac surgery. Despite this, relative changes of CO and ScO2 correlated significantly.

It is complicated to compare the results of the present study to the existing literature head-to-head, due to heterogeneity in study designs and settings. Our study is methodologically different from many other studies investigating the hemodynamic effects of a FC, since we had pre-specified time points for the FCs, which we integrated with standard clinical care of our patients (i.e. those accommodating the inclusion criteria). Across fluid responsiveness studies, around 50% of included patients are non-responders to a FC [17]. This is similar in our study, despite the difference in study design. While a different design could have altered the study findings, we find it difficult to speculate what differences to expect.

In the most frequently used intervention algorithm [7] the suggestion to increase ScO2 through an increase in CO is based on two small studies: one study reporting that ScO2 decreased in patients with normotensive acute heart failure and improved when heart failure was treated [12], and one study showing that ScO2 decreased during exercise in patients with left ventricular dysfunction [13]. In the CPB setting it has previously been described in a study testing the intervention algorithm, that increasing pump blood flow was the most successful instrument to minimize cerebral desaturation measured with NIRS [8] even though different pump flow levels have been shown not to affect the cerebral blood flow during CPB [18]. Furthermore, a recently published physiological proof of concept study showed that an increase in CPB pump flow lead to an increase in MAP and an increase in ScO2 whereas administration of phenylephrine and vasopressin increased MAP but decreased ScO2 [19]. In a randomised trial with two distinct levels of MAP during CPB with fixed pump flow the high MAP target group had lower NIRS values compared to the low MAP target group [20]. Conversely, in the off-pump setting, a study investigating the relationship of central venous oxygen saturation and ScO2 during a FC after cardiac surgery found no differences in ScO2 before and after FC for either fluid responders or non-responders [14]. However, central venous oxygen saturation was significantly higher for responders after FC whereas it did not change in non-responders. Unfortunately, we did not measure central venous oxygen saturation in the present study at relevant time points.

It was previously described that even though the patient remains within the MAP limits of cerebral autoregulation, the changes in CO can affect ScO2 [21]. The MAP levels for the patients in the present study also stayed within the assumed limits of cerebral autoregulation, as presented in Table 2, both before and after FC for both fluid responders and non-responders, although it has been shown that the limits of autoregulation may differ markedly between individuals [22,23,24]. With regard to cerebral autoregulation it was previously described that the lower limit of autoregulation seems to vary when the central blood volume or CO were lowered [25,26,27,28], which needs to be taken into account when evaluating the effect of a FC. In cases where CO is distinctively low, a FC may generate more pronounced responses in cerebral blood flow and subsequently in ScO2. Another factor to keep in mind when interpreting the effect of a FC on ScO2 is the possible “contamination” of the signal by extracranial perfusion [29], potentially causing a false increase in the NIRS readings. No matter the underlying explanation, we believe the resulting effect of a FC on ScO2 can be evaluated per se, which is further emphasized by the Figs. 2 and 3 illustrating an immediate response minute by minute during the FC. We chose to report both relative and absolute values of ScO2 since baseline values can vary markedly between individuals [30]. To facilitate the clinical interpretation, we kept relative changes as the primary outcome since it is an optimal way to reflect results in the individual patient due to individual differences in baseline values.

The relative increase in ScO2 was on average 2% for fluid responders, in absolute ScO2 values this increase was 1%, but both turned out statistically non-significant.

Despite the statistically significant observations of correlation between CO and ScO2, one must keep in mind that the clinical relevance of a difference as found in the present study is uncertain. It is very difficult to define a clinically relevant threshold of ScO2 levels and the definition of cerebral desaturation assessed with NIRS is vague [31]. Patient characteristics, or intraoperative data including haematocrit, can possibly influence the ScO2 readings [32, 33]. We observed a comparable haemodilution during surgery for fluid responders and non-responders—obviously due to the administered fluid in each FC. Therefore, when interpreting the results of the present study, the effect on ScO2 of a FC may be less than expected, since the tool to increase CO in this study also generates haemodilution. Therefore, other methods to increase CO without causing haemodilution (e.g. blood transfusions) might show a more pronounced increase in ScO2.

The present study has several limitations. Since this study is a substudy and a retrospective analysis of a clinical trial, no sample size calculation was performed. The main result was not significant and it may be caused by a type 2 error. As this study is a retrospective analysis, it was not designed to test the effect of a FC with a higher volume, which may have caused a more distinct response in ScO2, since hemodynamic variables demonstrated signs of hypovolaemia before—and for some patients after—FC. Only half of the possible data sets were complete and suitable for analysis and therefore no imputation method was used. The NIRS readings can possibly differ between different manufactures, as previously reported [29]. Therefore, the results may be interpreted with caution when comparing it with that of other studies using different NIRS devices.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study support the current guidelines to increase CO when it comes to maintain ScO2 values, but only in conditions where patients are fluid responsive. The clinical impact of small deviations in ScO2 on patient outcome is barely described and this study is only indicative that ScO2 may be augmented through fluid-induced increases in CO due to the demonstrated correlation between relative changes in ScO2 and CO.

Data availability

The dataset used and analyzed in the present study is available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Ahonen J, Salmenperä M. Brain injury after adult cardiac surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:4–19.

Roach GW, Kanchuger M, Mangona CM, Newman M, Nussmeier N, Wolman R, et al. Adverse cerebral outcomes after coronary bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1857–63.

Scheeren TWL, Kuizenga MH, Maurer H, Struys MMRF, Heringlake M. Electroencephalography and brain oxygenation monitoring in the perioperative period. Anesth Analg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002812.

Scheeren TWL, Schober P, Schwarte LA. Monitoring tissue oxygenation by near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS): background and current applications. J Clin Monit Comput. 2012;26:279–87.

Frost E. Cerebral oximetry: emerging applications for an established technology. Anesthesiol News. 2012;1–8.

Scheeren TWL, Bendjelid K. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing 2014 end of year summary: near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). J Clin Monit Comput. 2015;29:217–20. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10877-015-9689-4. Accessed 27 May 2019.

Denault A, Deschamps A, Murkin JM. A proposed algorithm for the intraoperative use of cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;11:274–81.

Murkin JM, Adams SJ, Novick RJ, Quantz M, Bainbridge D, Iglesias I, et al. Monitoring brain oxygen saturation during coronary bypass surgery: a randomized, prospective study. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:51–8.

Slater JP, Guarino T, Stack J, Vinod K, Bustami RT, Brown JM, et al. Cerebral oxygen desaturation predicts cognitive decline and longer hospital stay after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:36–45.

Deschamps A, Hall R, Grocott H, Mazer D, Choi PT, Turgeon A, et al. Cerebral oximetry monitoring to maintain normal cerebral oxygen saturation during high-risk cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:1–11.

Yu Y, Zhang K, Zhang L, Zong H, Meng L, Han R. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for perioperative monitoring of brain oxygenation in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD010947.

Madsen PL, Nielsen HB, Christiansen P. Well-being and cerebral oxygen saturation during acute heart failure in humans. Clin Physiol. 2000;20:158–64.

Koike A, Itoh H, Oohara R, Hoshimoto M, Tajima A, Aizawa T, et al. Cerebral oxygenation during exercise in cardiac patients. Chest. 2004;125:182–90. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.1.182.

Fellahi JL, Fischer MO, Rebet O, Dalbera A, Massetti M, Gérard JL, et al. Cerebral and somatic near-infrared spectroscopy measurements during fluid challenge in cardiac surgery patients: a descriptive pilot study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013;27:266–72. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2012.04.017.

Hilly J, Pailleret C, Fromentin M, Skhiri A, Bonnard A, Nivoche Y, et al. Use of near-infrared spectroscopy in predicting response to intravenous fluid load in anaesthetized infants. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2015;34:265–70.

Vistisen ST, Berg JM, Boekel MF, Modestini M, Bergman R, Jainandunsing JS, et al. Using extra systoles and the micro-fluid challenge to predict fluid responsiveness during cardiac surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10877-018-0218-0. Accessed 27 May 2019.

Messina A, Pelaia C, Bruni A, Garofalo E, Bonicolini E, Longhini F, et al. Fluid challenge during anesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:1353–64.

Slater JM, Orszulak TA, Cook DJ. Distribution and hierarchy of regional blood flow during hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:542–7.

Sperna Weiland NH, Brevoord D, Jöbsis DA, de Beaumont EMFH, Evers V, Preckel B, et al. Cerebral oxygenation during changes in vascular resistance and flow in patients on cardiopulmonary bypass—a physiological proof of concept study. Anaesthesia. 2016;72:1–8.

Holmgaard F, Vedel AG, Lange T, Nilsson JC, Ravn HB. Impact of 2 distinct levels of mean arterial pressure on near-infrared spectroscopy during cardiac surgery: secondary outcome from a randomized clinical trial. Anesth Analg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000003418.

Meng L, Hou W, Chui J, Han R, Gelb AW. Cardiac output and cerebral blood flow. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:1198–208. https://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00000542-201511000-00034. Accessed 27 May 2019.

Joshi B, Hogue CW. Predicting the limits of cerebral autoregulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:503–10.

Moerman AT, Vanbiervliet VM, Van Wesemael A, Bouchez SM, Wouters PF, De Hert SG. Assessment of cerebral autoregulation patterns with near-infrared spectroscopy during pharmacological-induced pressure changes. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:327–35. http://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00000542-201508000-00018. Accessed 27 May 2019.

Hori D, Hogue CW, Shah A, Brown C, Neufeld KJ, Conte JV, et al. Cerebral autoregulation monitoring with ultrasound-tagged near-infrared spectroscopy in cardiac surgery patients. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:1187–93.

Levine BD, Giller CA, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG. Cerebral versus systemic hemodynamics during graded orthostatic stress in humans. Circulation. 1994;90:298–306. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.CIR.90.1.298. Accessed 27 May 2019.

Brown CM, Dütsch M, Hecht MJ, Neundörfer B, Hilz MJ. Assessment of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular responses to lower body negative pressure as a test of cerebral autoregulation. J Neurol Sci. 2003;208:71–8.

Ogoh S, Brothers RM, Barnes Q, Eubank WL, Hawkins MN, Purkayastha S, et al. The effect of changes in cardiac output on middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity at rest and during exercise. J Physiol. 2005;569:697–704. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095836. Accessed 27 May 2019.

Ogawa Y, Iwasaki KI, Aoki K, Shibata S, Kato J, Ogawa S. Central hypervolemia with hemodilution impairs dynamic cerebral autoregulation. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1389–96.

Davie SN, Grocott HP. Impact of extracranial contamination on regional cerebral oxygen saturation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:834–40.

Heringlake M, Garbers C, Käbler J-H, Anderson I, Heinze H, Schön J, et al. Preoperative cerebral oxygen saturation and clinical outcomes in cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:58–69.

Nenna A, Barbato R, Greco SM, Pugliese G, Lusini M, Covino E, et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy in adult cardiac surgery: between conflicting results and unexpected uses. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14:659–61.

Kobayashi K, Kitamura T, Kohira S, Torii S, Horai T, Hirata M, et al. Factors associated with a low initial cerebral oxygen saturation value in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Artif Organs. 2017;20:110–6.

Nielsen HB. Systematic review of near-infrared spectroscopy determined cerebral oxygenation during non-cardiac surgery. Front Physiol. 2014;5:1–15.

Funding

Holmgaard was financially supported by the Research Foundation at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark, and the Heart Centre Research Foundation at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark. Vistisen was financially supported by The Danish Medical Research Council (DFF: 4183-00540) and the Danish Society for Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design—all authors. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data—FH, STV, TWLS. Drafting of the manuscript—all authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and final approval—all authors. Statistical analysis—FH, STV. Obtaining funding—all authors. Administrative, technical, or material support—all authors. Study supervision—STV, HBR, TWLS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

TWLS received Research Grants and Honoraria from Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, CA, USA) and Masimo, Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA) for consulting and lecturing and from Pulsion Medical Systems SE (Feldkirchen, Germany) for lecturing in the past. TWLS is Associate Editor of the Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing but had no role in the handling of this paper.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in were in accordance with the Ethical Standards of the Institutional and/or National Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the present study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Holmgaard, F., Vistisen, S.T., Ravn, H.B. et al. The response of a standardized fluid challenge during cardiac surgery on cerebral oxygen saturation measured with near-infrared spectroscopy. J Clin Monit Comput 34, 245–251 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-019-00324-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-019-00324-w