Abstract

Since August 2017, the Kuroshio has taken a large-meander (LM) path, which has forced the Kuroshio extension (KE) to be in its stable state against its wind-forced decadal variability. How such current conditions have impacted the formation and advection of North Pacific subtropical mode water (STMW) over its distribution region was examined using Argo float data during 2005–2020. Out of the whole STMW defined as a low-potential vorticity layer of 16–19.5 ºC, a relatively cold variety of 16–18 ºC, which was formed south of the KE and advected westward and southward, occupied more than 80% of the total volume. The formation rate of the 16–18 ºC variety was low during 2006–2009 in an unstable-KE period and high during 2010–2015 in a stable-KE period, and then dropped drastically in 2016 despite the KE still being in the stable state. After a short unstable-KE period in 2016–2017, the LM-forced, stable-KE period began, but the formation rate of the 16–18 ºC variety has not restored, possibly due to stronger background stratification propagated from the central North Pacific. In addition, the 16–18 ºC variety has had to make a southern detour around the LM, and its westward advection from the formation region south of the KE to the region south of Japan has been significantly decreased, possibly because it is dissipated more strongly over a southern part of the Izu–Ogasawara Ridge. Due to such decline in the formation and advection, the volume of the 16–18 ºC variety and hence that of the whole STMW have gradually decreased since 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Kuroshio has taken a large-meander (LM) path south of Japan since August 2017 (Usui 2019). The LM path frequently occurred in 1975–1991 (Kawabe 1995). Then, a non-large-meander (NLM) path (i.e., a nearshore NLM path and an offshore NLM path) had dominated for a quarter century, except for a 1-year LM period from July 2004 through August 2005.

The LM occurrence impacts currents and water masses in the surrounding area. Recently, it reset the decadal variability of the Kuroshio extension (KE) system (Qiu et al. 2020), which had been controlled by the wind stress curl variability in the central North Pacific associated with the Pacific decadal oscillation (PDO; Mantua et al. 1997) and the subsequent westward propagation of sea surface height (and main thermocline depth) anomalies as baroclinic Rossby waves (Qiu and Chen 2005; Qiu et al. 2007). The KE transitioned from a stable state to an unstable state in mid-2016 when negative sea surface height anomalies generated in the warm PDO phase since 2014 started arriving in the area east of Japan, and was predicted to remain in the unstable state for several years (Qiu et al. 2014, 2020). However, the KE unexpectedly switched back to the stable state in late 2017, because when the Kuroshio takes an LM path, its passage over a northern channel of the Izu Ridge (Kawabe 1985) stabilizes the KE path in the downstream (Qiu and Chen 2005; Sugimoto and Hanawa 2012; Qiu et al. 2020). Thus, the KE has been in the stable state since 2010, except for a short unstable period in 2016–2017.

The Kuroshio LM also influences the North Pacific Subtropical Mode Water (STMW; Masuzawa 1969), which is formed as deep winter mixed layers south of the Kuroshio and the KE (Suga and Hanawa 1990) and advected southwestward by the mean flow in the southern part of the Kuroshio recirculation gyre (Suga and Hanawa 1995a) and by eddy activities (Uehara et al. 2003; Nishikawa et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2014, 2016, 2017a; Nakano et al. 2021). By analyzing climatological data and the repeat hydrographic section along the 137ºE meridian, earlier studies (Suga et al. 1989; Suga and Hanawa 1995a, b) demonstrated that the westward advection of STMW from the region south of the KE to the region south of Japan was interrupted during LM periods because the LM divided the Kuroshio recirculation gyre into two parts. On the other hand, Oka et al. (2019), who recently calculated the cross-sectional area of STMW in the same 137ºE section in 1967–2016, pointed out that the cross-sectional area dropped significantly during the longest observed LM period of 1975–1980, but did not fall in the other, shorter LM periods. There is, as such, a need to examine how these results can reconcile with each other.

STMW has also been modulated by the decadal variability of the KE system. For more than two decades since 1993 (Qiu and Chen 2006; Rainville et al. 2014; Oka et al. 2015; Cerovečki and Giglio 2016), or possibly since late 1970s (Oka et al. 2019), the STMW formation south of the KE has decreased (increased) during unstable (stable) KE periods, presumably because enhanced (reduced) input of high-potential vorticity water north of the KE into the STMW formation region south of the KE hinders (facilitates) deepening of winter mixed layers there (Qiu and Chen 2006; Oka et al. 2015). It is of interest to examine whether such decadal STMW formation variability is still valid in recent years when the Kuroshio LM has been stabilizing the KE in spite of the arrival of PDO-related negative sea surface height anomalies from the central North Pacific.

The current Kuroshio LM period since August 2017 has already exceeded three years, being the second longest observed period. In addition, it is different from the longest observed period of 1975–1980 in that the large-scale circulation of STMW is fully monitored by the Argo profiling float network (Roemmich et al. 2001; Oka 2009; Oka et al. 2015). Utilizing this opportunity, this paper examines the formation and advection of STMW over its entire distribution region in relation to a persisting Kuroshio LM and the resultant stable state of the KE. The accompanying paper (Nishikawa et al. in prep.) investigates how anomalously warm STMW, which is formed in the recirculation gyre off Shikoku when the Kuroshio takes an LM path or an offshore NLM path (Sugimoto and Hanawa 2014), has been formed and maintained in the current LM period.

2 Data and method

We used temperature (T) and salinity (S) data from Argo profiling floats in the North Pacific in 2005–2020, which were downloaded from the ftp site of the Argo Global Data Assembly Center (ftp://usgodae.org/pub/outgoing/argo, ftp://ftp.ifremer.fr/ifremer/argos, https://doi.org/10.17882/42182) and edited as outlined in Oka et al. (2007). After discarding profiles shallower than 500 dbar and those in marginal seas, we vertically interpolated each profile onto a 1-dbar grid using the Akima spline (Akima 1970).

We also used T and S data obtained along the 137ºE section by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) biannually in winter (latter half of January) since 1967 and in summer (around July) since 1972, up to 2020 (Oka et al. 2018). Gridded T and S data at every 20’–1º meridional and 1 dbar vertical interval are made using optimal interpolation by the JMA and are publicly available online (http://www.data.jma.go.jp/gmd/kaiyou/db/mar_env/results/OI/137E_OI_e.html). Note that the gridded data used in this study are different from those used in our previous studies (Oka et al. 2017, 2018, 2019), as the JMA revised the optimal interpolation procedures in 2018. This yields slightly different values of STMW properties from our previous studies.

From the Argo float and 137ºE T/S data, we calculated potential temperature (θ), potential density (σθ), and potential vorticity (Q). Here, Q is defined as Q = gf ∂σθ/∂p, neglecting relative vorticity (Qiu et al. 2006), where g is the gravity acceleration, f the Coriolis parameter, and p is pressure. Using these values, STMW in the 137ºE section in 1967–2020 was detected as non-outcropping areas with θ = 15.0–19.5ºC and Q < 2.0 × 10–10 m−1 s−1, as in Oka et al. (2019). STMW in Argo profiles in 2005–2020 is defined as layers with θ = 16.0–19.5 ºC and Q < 2.0 × 10–10 m−1 s−1, except for those existing only at depths less than 100 dbar. This definition differs from that used in our previous studies using Argo profiles, i.e., a layer where Q is lower than 2.0 × 10–10 m−1 s−1 and θ at the Q minimum (called core θ hereafter) is between 16 and 19.5 °C (Oka 2009; Oka et al. 2011, 2015). In the new definition, we permit the existence of more than one STMW layer in each profile, which has been frequently observed in mode waters (Taneda et al. 2000; Oka et al. 2011, 2020; Gao et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2017, 2019). It should also be noted that the θ range for the STMW definition is different between the 137ºE and Argo float data; the narrower and relatively warm θ range for the more contemporary Argo data reflects long-term warming of STMW (Sugimoto et al. 2017; Oka et al. 2019).

3 Results

The time series of cross-sectional area of STMW in the 137ºE section (Oka et al. 2019) was extended to the latest observation in summer 2020 (Fig. 1). Since mid-1970s, the cross-sectional area had increased (decreased) during stable (unstable) KE periods with a time lag of about one year, as demonstrated by Oka et al. (2019). Since 2016, however, it has declined greatly in spite of the prolonged stable-KE period. Such decadal variations were commonly observed in the winter and summer 137ºE sections.

Time series of cross-sectional area of STMW in the 137ºE section in winter (blue) and summer (red). Thin curve with dots and thick curve denote the yearly values and values smoothed with a 1-3-4-3-1 filter, respectively. Solid (dotted) bars indicate stable (unstable) periods of the KE during 1977–1992 based on a numerical hindcast (Qiu et al. 2014) and after 1992 based on satellite altimeter data (Qiu et al. 2020). Shade denotes LM periods of the Kuroshio

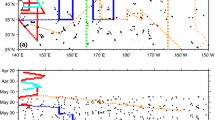

Decomposition of the cross-sectional area into θ bins reveals that the STMW in the winter 137ºE section consisted mainly of 16–17 ºC and 17–18 ºC varieties, the sum of which well explained the decadal variability of the total cross-sectional area (Fig. 2a). In addition, there are smaller contributions by the 15–16 ºC variety, mainly prior to mid-1990s, and the 18–19 ºC variety after mid-1990s, which also reflects the long-term warming of STMW. To examine in which region each variety of STMW was formed in the past 15 years, zonal distribution of core θ in spring was plotted over the formation region using Argo profiles (Fig. 3). As demonstrated by previous studies (Suga and Hanawa 1990; Oka and Suga 2003), colder STMW tended to be formed toward the east, but the zonal change of core θ was not continuous. In most years, relatively cold STMW of 16–18 ºC was formed east of 140ºE, while relatively warm STMW of 18–19.5 ºC was formed west of 150ºE and intensively west of 140ºE. There seems to be a gap of core θ near 140ºE, as demonstrated by Sugimoto and Hanawa (2014) for LM and offshore NLM periods of the Kuroshio during which the Kuroshio recirculation gyre split into two parts. Thus, STMW appearing in the winter 137ºE section consists mainly of that colder than 18 ºC formed south of the KE.

Time series of cross-sectional area of STMW (black) and its components with θ = 15–16 ºC (blue), 16–17 ºC (cyan), 17–18 ºC (green), 18–19 ºC (orange), 19–19.5 ºC (red), and 16–18 ºC (white) in the 137ºE section in a winter and b summer. Bars and shade denote stable/unstable periods of the KE and LM periods of the Kuroshio, respectively

In the summer 137ºE section (Fig. 2b), the 16–17 ºC and 17–18 ºC varieties dominated the KE-related decadal variability, as in the winter section. In addition, the 18–19 ºC variety originating near the 137ºE section occupied a comparable cross-sectional area to the 16–17 ºC and 17–18 ºC varieties, except in LM periods during which the 18–19 ºC variety almost disappeared. Argo float data supportively exhibit that in the late winters of 2005 and 2018–2020 during the LM period, the 19–19.5 ºC variety was formed south of Japan and the 16–17 ºC and 17–18 ºC varieties were formed south of the KE, while the 18–19 ºC variety was absent (Fig. 3).

Since 2016, not only the 18–19 ºC variety in the summer 137ºE section but also the 16–17 ºC and 17–18 ºC varieties in both the winter and summer sections have shrunk (Fig. 2). This suggests that the westward advection of STMW from the region south of the KE has been interrupted by the LM since summer 2017, as demonstrated by the previous studies (Suga et al. 1989; Suga and Hanawa 1995a,b). There is also a possibility that the STMW formation south of the KE has decreased, possibly in relation to the LM. Therefore, Argo float data will be analyzed next to examine the formation and advection of STMW over its entire distribution region in the past 16 years.

The STMW thickness from individual Argo float profiles (if there are more than one STMW layer in a profile, their thickness was summed up) was horizontally interpolated and mapped for each month in the same manner as Oka et al. (2015). Due to the change in the STMW definition (Sect. 2), the total volume of STMW in the study region of 15–40ºN, 120ºE − 170ºW during 2005–2014 (black curve in Fig. 4) is larger than that presented by Oka et al. (2015; their Fig. 7a) by 9% on average, while the two time series exhibit similar seasonal and decadal variability (correlation coefficient = 0.98), including a decrease in 2006 − 2009 in the unstable KE period and an increase after 2010 in the stable KE period. Since 2016, the total volume has gradually declined in spite of the extended stable-KE period, exhibiting the same tendency as observed in the cross-sectional area in the 137ºE section (Fig. 1).

Monthly time series of volume of STMW in the whole study region (black) and the NE (red), NW (orange), SE (blue), and SW (cyan) regions, based on Argo float data. Solid (dotted) bars indicate stable (unstable) periods of the KE based on satellite altimeter data (Qiu et al. 2020). Shade denotes LM periods of the Kuroshio

Oka et al. (2015) divided the STMW volume into two regions north and south of 28ºN where STMW is ventilated and unventilated, respectively (Oka and Suga 2003; Oka 2009). We further divide these regions zonally at 140ºE where the gap of core θ existed (Fig. 3), defining four regions: the NE region at 28–40ºN, 140ºE–170ºW, the NW region at 28–40ºN, 120–140ºE, the SE region at 15–28ºN, 140ºE–170ºW, and the SW region at 15–28ºN, 120–140ºE (Fig. 4). In the NE region, the STMW volume exhibited a distinct seasonal variation with a maximum in February–April and a minimum in November–December. The volume in the NW region showed a less clear seasonal variation with a maximum around February–May and a minimum around September–December. Seasonal variations were much smaller in the SE and SW regions, indicating that STMW observed in these regions were formed in the NE and NW regions and advected southward. As the formation location within the NE and NW regions critically depends on the θ of STMW (Fig. 3), it is instructive to also decompose the STMW volume into θ bins.

The volume of the 16–18 ºC variety (Fig. 5a) accounted for the great majority of the whole STMW layer (16–19.5 ºC; Fig. 4), as in the 137ºE section (Fig. 2), and exhibited a similar variation to the whole STMW layer in each region, except in the NW region where the 16–18 ºC variety lacked seasonality. Seasonal variations were seen only in the NE region where the volume reached a maximum in March–April and a minimum in November–December. The 16–18 ºC variety is formed in this region and advected westward and southward to the other three regions.

a Monthly time series of volume of STMW with θ = 16–18 ºC, otherwise following Fig. 4. b Time series of formation volume (red) and erosion volume (blue) of STMW with θ = 16–18 ºC in the NE region. Here the formation volume (erosion volume) is calculated for each year as the difference between the maximum volume in late winter and the minimum volume in the previous fall (in the following fall), as in Oka et al. (2015)

The formation volumeFootnote 1 of the 16–18 ºC variety in the NE region was small (0.21 × 1015 m3 on average) during 2006–2009 in the unstable KE period and large (0.38 × 1015 m3) during 2010–2015 in the stable KE period (Fig. 5b). It tended to be smaller (larger) than the erosion volume during the former (latter) period, causing a decadal variation of volume in this region with a minimum in 2009 and a maximum in 2014 (Fig. 5a). This decadal volume variation spread to the other regions through advection; the annual-mean volume in the NW, SE, and SW regions during 2005–2015 was highly correlated (coefficient > 0.9) with that in the NE region when lagged by 1 year.

In 2016, the formation volume dropped to 0.23 × 1015 m3 despite the KE still being in the stable state (Fig. 5b). Late winter mixed layers in the NE region of this year were anomalously shallow (Fig. 6) and warm (Fig. 3), and became relatively thin STMW over an unventilated, colder STMW layer formed in the previous year. (Such insufficient development of mixed layers in the NE region in the late winter of 2016 will be an interesting theme for future studies.) The formation volume increased to 0.35 × 1015 m3 in 2017 in the short unstable-KE period, but did not recover any further in the following LM-forced stable-KE period (Fig. 5b). The formation volume during 2018–2020 was 0.28 × 1015 m3 on average, an intermediate value between the 2006–2009 unstable-KE and 2010–2015 stable-KE periods.

a Distribution of mixed layer depth in March where θ at 10-dbar depth is 16–18 ºC, based on Argo float data. Mixed layer depth, which is defined as the shallower value of the depth at which σθ increases by 0.125 kg m−3 from 10-dbar depth and that at which θ changes by 0.5 ºC from 10-dbar depth (e.g., Levitus 1982; Suga et al. 2004), was computed for each float profile and then mapped in the same manner as the STMW thickness. b Monthly time series of mixed layer volume where θ at 10-dbar depth is 16–18 ºC in the region of 15–40ºN, 120ºE–170ºW, based on Argo float data

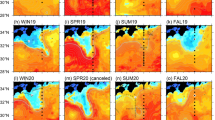

Furthermore, the lagged relationship between the annual-mean volume in the NE region and that in the three other downstream regions observed in 2005–2015 seems to have failed since the current LM period began. During the unstable-KE period of 2006–2009, the annual-mean volume of the 16–18 ºC variety dropped by 26% from 2006 to 2008 in the NE region and by 32, 48, and 50% from 2007 to 2009 in the SE, NW, and SW regions, respectively (Fig. 5a). At the beginning of the stable-KE period since 2010, the annual-mean volume increased by 68% from 2010 to 2012 in the NE region and by 32, 181, and 185% from 2011 to 2013 in the three other regions. After the current LM began, however, the annual-mean volume in the NE region increased by 6% from 2017 to 2019, while that in the SE, NW, and SW regions dropped by 22, 36, and 39%, respectively, from 2018 to 2020. The unanticipated volume decline in the downstream regions, particularly the larger decrease in the NW and SW regions west of 140ºE, suggests that the westward advection of STMW was interrupted by the LM, as demonstrated by the previous studies. When we look at the thickness distributions of the 16–18 ºC variety in recent years (Fig. 7), the 16–18 ºC variety thicker than 100 dbar had been advected westward from the region south of the KE to the region south of Japan prior to mid-2017. Since the current LM began, the 16–18 ºC variety has had to make a southern detour around the LM to enter the region south of Japan, which likely led to the decreasing advection with time. Thus, the reduced formation in the NE region since 2016 and the decreasing advection to the downstream regions since 2018 have contributed to the decline of annual-mean total volume of the 16–18 ºC variety from 0.74 × 1015 m3 in 2015 to 0.55 × 1015 m3 in 2020 (Fig. 5a).

The 18–19 ºC variety occupied a much smaller volume than the 16–18 ºC variety (Fig. 8). Its volume in the NE region exhibited a seasonal variation with a maximum in January–February (Fig. 8a), which is 2 months earlier than the peak of the 16–18 ºC variety in this region (Fig. 5a). This implies that some portion of the 18–19 ºC variety observed in January–February was further cooled to become the 16–18 ºC variety in March–April. Consistently, the 18–19 ºC variety widely spread over the NE region in January–February (not shown), but was found mostly west of 150ºE in April (Fig. 9).

Distribution of thickness of STMW with θ = 18–19 ºC, otherwise following Fig. 7

The 18–19 ºC variety was also formed in the NW region and, to the less extent, in the SE and SW regions south of 28ºN, where its volume was at a peak in March–April of particular years such as 2006, 2008, 2011–2015, and 2017 (Figs. 8b–d, 9). On the other hand, its formation in the NW region almost ceased in 2005 and 2018–2020 during the LM period, as observed in the 137ºE section (Fig. 2). After spring, the 18–19 ºC variety shrank before being substantially advected southward (Fig. 9). Its volume in the NW and SW regions tended to be larger in July than in the following January (Fig. 8b, d), which is consistent with its cross-sectional area in the 137ºE section being larger in summer than in winter (Fig. 2).

The 19–19.5 ºC variety also occupied a small volume in the whole STMW layer (Fig. 10). In the NE region, its volume reached a maximum mostly in January and was small after spring (Fig. 10a). Such a seasonal variation probably reflected the formation process of colder varieties of STMW and not that of the 19–19.5 ºC variety. In the NW region, the 19–19.5 ºC variety had the largest volume in March–May (in other words, it was formed) in 2005, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2016, 2018, and 2020 (Figs. 10b, 11). Interestingly, these were the years in which the 18–19 ºC variety was not formed in this region (Fig. 8b). The formation of the 19–19.5 ºC variety in 2018 and 2020 in the current LM period supports Sugimoto and Hanawa (2014), who analyzed Argo float data in 2005–2011 to demonstrate that STMW warmer than 19 ºC was formed in the recirculation gyre south of Japan when the Kuroshio took an LM or offshore NLM path.

Monthly time series of volume of STMW with θ = 19–19.5 ºC in the whole region (a; black curve) and the NE (a; red curve), NW (b), SE (c), and SW (d) regions, otherwise following Fig. 4

Distribution of thickness of STMW with θ = 19–19.5 ºC, otherwise following Fig. 7

Like the 18–19 ºC variety, the 19–19.5 ºC variety shrank after spring and almost disappeared by fall, but exceptionally survived for more than one year south of Japan in 2018–2019 (Figs. 10b, 11). Its formation and temporal evolution in relation to colder varieties of STMW in the current LM period will be detailed in our accompanying paper (Nishikawa et al. in prep.).

4 Discussion

Replotting the volume of the 16–18 ºC, 18–19 ºC, and 19–19.5 ºC varieties together for each region (Fig. 12) confirms the dominance of the 16–18 ºC variety in the NE, SE, and SW regions. In the NE region where the 16–18 ºC variety is formed, it had an average volume of 0.31 × 1015 m3 during 2005–2020, occupying 84% of the whole STMW layer (Fig. 12b). This ratio increased up to 91% when only values in April–December without formation months were considered. In the SE and SW regions south of 28ºN where the 16–18 ºC variety is not ventilated, its volume amounted to 0.24 × 1015 m3 on average, occupying 88% (Fig. 12d, e). The ratio was also high (82% on the annual average and 86% for April–December) in the whole study region (Fig. 12a).

Monthly time series of volume of STMW with θ = 16 − 18 ºC (blue), 18–19 ºC (green), 19–19.5 ºC (red) in the whole study region (a) and the NE (b), NW (c), SE (d), and SW (e) regions, otherwise following Fig. 4

The 16–18 ºC variety is also the only variety that had fluctuated decadally in all regions in relation to the decadal KE variability until 2015. What made its formation volume in the NE region during 2018–2020 in the current, LM-forced stable-KE period considerably smaller than that during 2010–2015 in the previous, wind-forced stable-KE period (Fig. 5b)? As the eddy activity in the KE region was low in both periods, the southward transport of high-Q and fresher water north of the KE to the STMW formation region, which presumably hinders deepening of winter mixed layers there (Qiu and Chen 2006; Oka et al. 2015), was expected to have stayed small. Another factor that can affect the STMW formation is the PDO-related sea surface height anomalies propagating from the central North Pacific, which had controlled the decadal KE variability until the current, LM-forced stable-KE period began. As negative sea surface height anomalies have been arriving since mid-2016, the associated stronger background stratification above the middle of the main thermocline (Qiu and Chen 2006; Sugimoto and Hanawa 2010) is expected to have hindered the STMW formation.

How is the westward advection of the 16–18 ºC variety from the NE region to the SW and SE regions interrupted by the LM? In addition to the longer advection route associated with the southern detour, enhanced diapycnal mixing over the Izu-Ogasawara Ridge along ~ 140ºE (Hibiya et al. 2007; Whalen et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2017b) might have an influence. Xu et al. (2017a) analyzed Argo float data in 2004–2016 to demonstrate that thick STMW, possibly trapped in anticyclonic eddies, preferentially passed through a bathymetric gap of the ridge near 30ºN. When the 16–18 ºC variety makes a southern detour and passes over the ridge south of the gap (Fig. 7), it might be dissipated more strongly there.

5 Summary

Argo float data in 2005–2020 have been analyzed to examine the formation and advection of STMW over its entire distribution region in relation to the recent, persisting LM of the Kuroshio and the LM-forced stable state of the KE. Out of the whole STMW defined as a low-Q layer of 16–19.5 ºC, a relatively cold variety of 16–18 ºC, which was formed east of 140ºE and north of 28ºN in late winter and then advected westward and southward (Fig. 13a), occupied more than 80% of the total volume. The formation volume of the 16–18 ºC variety was small during 2006–2009 in an unstable-KE period and large during 2010–2015 in a stable-KE period, and then dropped drastically in 2016, in which late winter mixed layers were anomalously shallow and warm despite the KE still being in its stable state. In 2018–2020 after the LM-forced, stable-KE period began, the formation volume of the 16–18 ºC variety has been intermediate between the small values in 2006–2009 and the large values in 2010–2015, possibly because the PDO-related stronger background stratification propagated from the central North Pacific was unfavorable for the winter mixed layer development. In addition, since the current LM began in summer 2017, the 16–18 ºC variety has had to make a southern detour around the LM, and its westward advection from the formation region south of the KE to the region south of Japan has been significantly decreased (Fig. 13b), possibly because it is dissipated more strongly over a southern part of the Izu-Ogasawara Ridge. Due to such decline in the formation and advection, the volume of the 16–18 ºC variety and hence that of the whole STMW have gradually decreased since 2016. The cross-sectional area of STMW in the 137ºE repeat hydrographic section has also dropped rapidly since 2016, as previously seen in the longest observed LM period of 1975–1980.

Schematic illustrating the formation and advection of STMW with θ = 16–18 ºC in a non-LM periods and b LM periods of the Kuroshio. Blue shading denotes the formation region. Light blue shading with thin black arrows represents advection from the formation region. Thick black arrow indicates the path of the Kuroshio and the KE

The 18–19 ºC variety of STMW was formed south of Japan and south of the KE west of 150ºE in late winter in some years, while the 19–19.5 ºC variety was formed south of Japan in the other years. After spring, both varieties rapidly shrank before being substantially advected southward and almost disappeared by fall. Since the current LM began, the 19–19.5 ºC variety was formed in the late winter of 2018, survived for more than a year, and was renewed in the late winter of 2020. These events will be described in detail in our accompanying paper (Nishikawa et al. in prep).

Notes

Both the formation volume and the erosion volume of the 16 − 18ºC variety in the NE region shown in Fig. 5b include the volume outflux from the NE region to the three other regions. In the following argument, we assume that the outflux and its year-to-year variation were small compared to the formation volume.

References

Akima H (1970) A new method of interpolation and smooth curve fitting based on local procedures. J Assoc Comput Math 17:589–602

Cerovečki I, Giglio D (2016) North Pacific Subtropical Mode Water volume decrease in 2006–09 estimated from Argo observations: influence of surface formation and basin-scale oceanic variability. J Clim 29:2177–2199

Gao W, Li P, Xie SP, Xu L, Liu C (2016) Multi-core structure of the North Pacific subtropical mode water from enhanced Argo observations. Geophys Res Lett 43:1249–1255

Hibiya T, Nagasawa M, Niwa Y (2007) Latitudinal dependence of diapycnal diffusivity in the thermocline observed using a microstructure profiler. Geophys Res Lett 34:L24602. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL032323

Kawabe M (1985) Sea level variations at the izu islands and typical stable paths of the kuroshio. J Oceanogr Soc Jpn 41:307–326

Kawabe M (1995) Variations of current path, velocity, and volume transport of the Kuroshio in relation with the large meander. J Phys Oceanogr 25:3103–3117

Levitus S (1982) Climatological atlas of the world ocean. NOAA professional paper 13. US Government Printing Office, Washington DC, p 173

Liu C, Xie SP, Li P, Xu L, Gao W (2017) Climatology and decadal variations in multicore structure of the North Pacific subtropical mode water. J Geophys Res 122:7506–7520

Liu C, Xu L, Xie SP, Li P (2019) Effects of anticyclonic eddies on the multicore structure of the North Pacific subtropical mode water based on Argo observations. J Geophys Res 124:8400–8413

Mantua NJ, Hare SR, Zhang Y, Wallace JM, Francis RC (1997) A Pacific interdecadal climate oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bull Amer Meteor Soc 78:1069–1079

Masuzawa J (1969) Subtropical mode water. Deep-Sea Res 16:463–472

Nakano H, Matsumura Y, Tsujino H, Urakawa S, Sakamoto K, Toyoda T, Yamanaka G (2021) Effects of eddies on the subduction and movement of water masses reaching the 137°E section using Lagrangian particles in an eddy-resolving OGCM. J Oceanogr 77:283–305

Nishikawa S, Tsujino H, Sakamoto K, Nakano H (2010) Effects of mesoscale eddies on subduction and distribution of Subtropical Mode Water in an eddy-resolving OGCM of the western North Pacific. J Phys Oceanogr 40:1748–1765

Oka E (2009) Seasonal and interannual variation of North Pacific Subtropical Mode Water in 2003–2006. J Oceanogr 65:151–164

Oka E, Suga T (2003) Formation region of North Pacific subtropical mode water in the late winter of 2003. Geophys Res Lett 30:2205. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL018581

Oka E, Talley LD, Suga T (2007) Temporal variability of winter mixed layer in the mid- to high-latitude North Pacific. J Oceanogr 63:293–307

Oka E, Suga T, Sukigara C, Toyama K, Shimada K, Yoshida J (2011) “Eddy-resolving” observation of the North Pacific Subtropical Mode Water. J Phys Oceanogr 41:666–681

Oka E, Qiu B, Takatani Y, Enyo K, Sasano D, Kosugi N, Ishii M, Nakano T, Suga T (2015) Decadal variability of subtropical mode water subduction and its impact on biogeochemistry. J Oceanogr 71:389–400

Oka E, Katsura S, Inoue H, Kojima A, Kitamoto M, Nakano T, Suga T (2017) Long-term change and variation of salinity in the western North Pacific subtropical gyre revealed by 50-year long observations along 137°E. J Oceanogr 73:479–490

Oka E, Ishii M, Nakano T, Suga T, Kouketsu S, Miyamoto M, Nakano H, Qiu B, Sugimoto S, Takatani Y (2018) Fifty years of the 137°E repeat hydrographic section in the western North Pacific Ocean. J Oceanogr 74:115–145

Oka E, Yamada K, Sasano D, Enyo K, Nakano T, Ishii M (2019) Remotely forced decadal physical and biogeochemical variability of North Pacific subtropical mode water over the last 40 years. Geophys Res Lett 46:1555–1561

Oka E, Kouketsu S, Yanagimoto D, Ito D, Kawai Y, Sugimoto S, Qiu B (2020) Formation of Central Mode Water based on two zonal hydrographic sections in spring 2013 and 2016. J Oceanogr 76:373–386

Qiu B, Chen S (2005) Variability of the Kuroshio Extension jet, recirculation gyre and mesoscale eddies on decadal timescales. J Phys Oceanogr 35:2090–2103

Qiu B, Chen S (2006) Decadal variability in the formation of the North Pacific Subtropical Mode Water: Oceanic versus atmospheric control. J Phys Oceanogr 36:1365–1380

Qiu B, Hacker P, Chen S, Donohue KA, Watts DR, Mitsudera H, Hogg NG, Jayne SR (2006) Observations of the subtropical mode water evolution from the Kuroshio extension system study. J Phys Oceanogr 36:457–473

Qiu B, Chen S, Hacker P (2007) Effect of mesoscale eddies on subtropical mode water variability from the Kuroshio Extension System Study (KESS). J Phys Oceanogr 37:982–1000

Qiu B, Chen S, Schneider N, Taguchi B (2014) A coupled decadal prediction of the dynamic state of the Kuroshio Extension system. J Clim 27:1751–1764

Qiu B, Chen S, Schneider N, Oka E, Sugimoto S (2020) On reset of the wind-forced decadal Kuroshio Extension variability in late 2017. J Clim 33:10813–10828

Rainville L, Jayne SR, Cronin MF (2014) Variations of the North Pacific subtropical mode water from direct observations. J Clim 27:2842–2860

Roemmich D, Boebel O, Desaubies Y, Freeland H, King B, LeTraon PY, Molinari R, Owens WB, Riser S, Send U, Takeuchi K, Wijffels S (2001) Argo: the global array of profiling floats. In: Koblinsky CJ, Smith NR (eds) Observing the Oceans in the 21st Century. GODAE Project Office, Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, pp 248–258

Suga T, Hanawa K (1990) The mixed layer climatology in the northwestern part of the North Pacific subtropical gyre and the formation area of Subtropical Mode Water. J Mar Res 48:543–566

Suga T, Hanawa K (1995a) The subtropical mode water circulation in the North Pacific. J Phys Oceanogr 25:958–970

Suga T, Hanawa K (1995b) Interannual variations of North Pacific Subtropical Mode Water in the 137°E section. J Phys Oceanogr 25:1012–1017

Suga T, Hanawa K, Toba Y (1989) Subtropical mode water in the 137°E section. J Phys Oceanogr 19:1605–1618

Suga T, Motoki K, Aoki Y, Macdonald AM (2004) The North Pacific climatology of winter mixed layer and mode waters. J Phys Oceanogr 34:3–22

Sugimoto S, Hanawa K (2010) Impact of Aleutian Low activity on the STMW formation in the Kuroshio recirculation gyre region. Geophys Res Lett 37:L03606. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL041795

Sugimoto S, Hanawa K (2012) Relationship between the path of the Kuroshio in the south of Japan and the path of the Kuroshio Extension in the east. J Oceanogr 68:219–225

Sugimoto S, Hanawa K (2014) Influence of Kuroshio path variation south of Japan on formation of subtropical mode water. J Phys Oceanogr 44:1065–1077

Sugimoto S, Hanawa K, Watanabe T, Suga T, Xie SP (2017) Enhanced warming of the subtropical mode water in the North Pacific and North Atlantic. Nat Clim Change 7:656–658

Taneda T, Suga T, Hanawa K (2000) Subtropical mode water variation in the southwestern part of the North Pacific subtropical gyre. J Geophys Res 105:19591–19598

Uehara H, Suga T, Hanawa K, Shikama N (2003) A role of eddies in formation and transport of North Pacific Subtropical Mode Water. Geophys Res Lett 30:1705. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL017542

Usui N (2019) Progress of studies on Kuroshio path variations south of japan in the past decade. Kuroshio Current: physical, Biogeochemical, and Ecosystem Dynamics. Wiley, pp 147–161

Whalen CB, Talley LD, MacKinnon JA (2012) Spatial and temporal variability of global ocean mixing inferred from Argo profiles. Geophys Res Lett 39:L18612. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL053196

Xu L, Li P, Xie S-P, McClean JL, Liu Q, Sasaki H (2014) Mesoscale eddy effects on the subduction of North Pacific mode waters. J Geophys Res 119:4867–4886

Xu L, Li P, Xie S-P, Liu Q, Liu C, Gao W (2016) Observing mesoscale eddy effects on mode-water subduction and transport in the North Pacific. Nat Commun 7:10505. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10505

Xu L, Xie SP, Liu Q, Liu C, Li P, Lin X (2017a) Evolution of the North Pacific subtropical mode water in anticyclonic eddies. J Geophys Res 122:10118–10130

Xu L, Xie SP, Jian Z, Wu L, Liu Q, Li P, Du Y (2017b) Observing subsurface changes of two anticyclonic eddies passing over the Izu-Ogasawara Ridge. Geophys Res Lett 44:1857–1865

Acknowledgements

This study was motivated by discussion made at University of Hawaii at Manoa where EO and SS had a sabbatical in 2019−2020. The authors thank Toshio Suga, Shigeki Hosoda, Yoshimi Kawai, Fumiaki Kobashi, Katsuya Toyama, Toru Miyama, Atsushi Kojima, Yuma Kawakami, and the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and support from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (KAKENHI, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) No. 21340133 and 25287118) and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (MEXT; Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas under Grant No. 19H05700 and 19H05704).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oka, E., Nishikawa, H., Sugimoto, S. et al. Subtropical Mode Water in a recent persisting Kuroshio large-meander period: part I—formation and advection over the entire distribution region. J Oceanogr 77, 781–795 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10872-021-00608-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10872-021-00608-3