Abstract

The thickness, the refractive index, and the optical anisotropy of thin sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) films, prepared by spin-coating or solvent deposition, have been investigated with spectroscopic ellipsometry. For not too high polymer concentrations (≤5 wt%) and not too low spin speeds (≥2000 rpm), the thicknesses of the films agree well with the scaling predicted by the model of Meyerhofer, when methanol or ethanol are used as solvent. The films exhibit uniaxial optical anisotropy with a higher in-plane refractive index, indicating a preferred orientation of the polymer chains in this in-plane direction. The radial shear forces that occur during the spin-coating process do not affect the refractive index and the extent of anisotropy. The anisotropy is due to internal stresses within the thin confined polymer film that are associated with the preferred orientations of the polymer chains. The internal stresses are reduced in the presence of a plasticizer, such as water or an organic solvent, and increase to their original value upon removal of such a plasticizer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The properties of membranes derived from sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) (SPEEK) have been investigated for many years. SPEEK films have a distinct thermo-chemical–mechanical stability. In addition, the degree of sulfonation (DS) of SPEEK can be changed, which can be beneficial for many applications. In the vanadium redox flow battery and fuel-cell applications, the sulfonic acid groups in SPEEK enable conductivity of protons [1–8]. In biorefinery applications and reverse electrodialysis, the sulfonic groups provide the possibility to exchange cations [9, 10]. The high affinity for water of the negatively charged groups empowers application of SPEEK membranes in dehydration processes [11–15]. Additionally, due to the amorphous structure and high glass transition temperature, SPEEK membranes have been considered good candidates for high-pressure gas separation [16–18].

Despite the merits, the high concentration of sulfonic acid groups also has drawbacks. In comparison to pure poly(ether ether ketone) (PEEK), the sulfonation of this material to SPEEK causes a significant reduction in thermal stability [19]. This reduction in stability becomes larger for a higher degree of sulfonation [20]. Generally, above 200 °C, chemical decomposition of SPEEK starts to occur, which is initiated from the sulfonated domains [21, 22]. Therefore, the thermal treatments that are frequently performed after formation of membranes to relieve stresses and remove solvents are challenging in the case of SPEEK. The effective removal of non-volatile, high boiling point casting solvents, such as N-methylpyrrolidinone (NMP) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is hindered [22] and alternative removal methods have been reported, such as rinsing out-of-DMSO in boiling water [23].

In addition, the highly non-equilibrium glassy state of polymeric films can be affected by high spin speeds or rapid solvent evaporation [24, 25]. These may cause polymer chains to orient in preferential directions. The preferred orientations of polymer chains induce internal stresses in the material that in turn can affect the permeability and the selectivity [26]. For many polymers, the heating above the glass transition temperature and subsequent thermal quenching remove the non-equilibrium characteristics. Concerning SPEEK, the study of Reyna-Valencia et al. has shown that membranes with a degree of sulfonation of 63 and 83 %, formed from solvent casting using N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc) and dimethylformamide (DMF), exhibited polymer chain orientations [27]. Notably, their study shows that repeated heating to temperatures close to the glass transition temperature causes reorganization of the material, with more pronounced preferential orientations of the polymer chains in the plane parallel to the surface of the film [27]. As such, SPEEK membranes are affected by their processing history and the thermal cycling results in relaxations that cause the material to become anisotropic, instead of isotropic.

In this paper, we focus on the relations between SPEEK film formation procedures and the molecular orientations in the obtained SPEEK films. Two techniques have been used for film preparation; spin-coating and solution deposition. For spin-coating, methanol and ethanol have been used as volatile organic solvents with distinct physical properties. For solution deposition, the volatile methanol and non-volatile NMP have been selected. Motivated by the study of Reyna-Valencia et al. [27], we conduct a systematic study on the effects of induced polymer relaxations on the internal stresses in SPEEK films, by changing the ambient relative humidity and the conditioning temperatures. The extent of polymer chain orientation is related to the optical anisotropy of the films [28], which in this study is determined with spectroscopic ellipsometry.

Theory

Spectroscopic ellipsometry

Spectroscopic ellipsometry is an optical method that is used to determine thickness and wavelength-dependent refractive indices (optical dispersion) of films atop a substrate. For a detailed explanation, the interested reader is referred to the book of Fujiwara [29]. In short, the method is based on measuring the change in the polarization state of p- and s-polarized light upon reflection at a surface. In practice, linearly polarized light is used as incident beam and after reflection the light has become, to a certain extent, elliptically polarized. The ellipticity is quantified by two angles: the amplitude component Psi (Ψ) (°) and phase difference Delta (Δ) (°). Combined, these can be expressed as the complex reflectance ratio, ρ (−):

where r p and r s is the reflectivity of the p- and s-polarized light (−), respectively.

The dispersion and thickness of a film are obtained by fitting an optical model to the experimentally obtained spectra. This is expedited using a simple expression for the dispersion. Various empirical expressions are available. For transparent isotropic materials, the Cauchy relation is generally considered appropriate [29]:

where n(λ) is the wavelength dependent refractive index (−), λ is the wavelength of the light (nm), and A, B, and C are coefficients that describes the dependency of the refractive index on the wavelength.

The quality of the fit of the optical model to the experimental data is given as the Mean Square Error (MSE). There is no fixed MSE value that resolves if a model can be considered correct or not. For thicker films and in-situ measurements, a maximum value of 20 is considered to be reasonable [30].

For anisotropic materials, the refractive index is dependent on the propagation direction of the light in the material. When the refractive index is different in all directions, n x ≠ n y ≠ n z , the material is referred to as biaxial anisotropic. Thin polymer films often exhibit uniaxial anisotropy, with a different refractive index in the direction perpendicular to the surface of the film n x = n y ≠ n z . The z-direction corresponds with the so-called optical axis, i.e., the axis of symmetry with all perpendicular directions optically equivalent. The difference between two refractive indices is called optical anisotropy, Δn, also termed birefringence. In this paper, we refer to Δn as to optical anisotropy. In the case of a uniaxial anisotropic material, the single optical anisotropy value is given by

Here, n xy is referred to as the in-plane refractive index (also termed ordinary) and n z is referred to as the out-of-plane refractive index (also termed extraordinary). The optical anisotropy is correlated with internal stresses in a material by the empirical equation [31]:

where σ 1 and σ 2 are principal in-plane and out-of-plane stresses (Pa), and C is the stress-optical coefficient (Pa).

Materials and methods

Materials

SPEEK was obtained by sulfonation of PEEK (Victrex, United Kingdom) using sulfuric acid according to the method reported by Shibuya et al. [32]. The degree of sulfonation determined by 1H NMR in DMSO-d6 using a AscendTM 400 (Bruker) at a resonance frequency of 400 MHz, according to the method described by Zaidi et al. [33], was 84 %. Methanol and ethanol (Emsure® grade of purity) were obtained from Merck (The Netherlands), NMP 99 % extra pure was obtained from Acros Organics (The Netherlands). DMSO-d6 (99.5 at.% D) was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (The Netherlands). Nylon Membrane 25-mm syringe filters 0.45 μm were obtained from VWR International. Polished, 〈100〉-oriented silicon wafers were obtained from Okmetic (Finland). Nitrogen gas (4.5) was supplied by Praxair (The Netherlands).

Film preparation

Films were coated on pre-cut pieces of a silicon wafer. Prior to coating, the solutions were filtered using a 0.45-μm syringe filter to remove solid contaminations. The two following methods were used for SPEEK film formation.

Spin-coating

Films were formed by spin-coating of SPEEK dissolved in either methanol or ethanol (3, 5, and 7 wt%). The spinning time was always 50 s. The spin speed was set at 1000, 2000, 3000, or 4000 rpm. All samples were prepared in duplicate; one part was treated under vacuum at 30 °C for 48 h, and the second part under vacuum at 140 °C for 48 h.

Solution deposition

Films were formed by deposition of SPEEK dissolved in methanol or N-methylpyrrolidone on the substrate and subsequent solvent evaporation. Thus, the spin speed was equal to zero. Prior to deposition from the SPEEK/NMP solution, the silicon wafers were pre-treated 20 min in oxygen plasma, in order to ensure NMP wettability of silicon waver. Without plasma treatment, the NMP solutions did not wet the wafers. All samples were prepared in duplicate; one part was treated under vacuum at 30 °C for 48 h, and the second part under vacuum at 140 °C for 48 h.

Ellipsometry measurements

An M-2000 spectroscopic ellipsometer (J.A. Woollam Co., Inc., USA) was used. The size of the light spot for the standard configuration was 2 mm. For the films obtained with the solution deposition technique, focusing probes were used with a light spot size of 150 μm. This was necessary to cope with the very extensive thickness variations within each of these films. Ex-situ experiments were conducted at three angles of incidence (55°, 65°, and 70°) for the initial investigations of the optical anisotropy of the SPEEK films. Further systematic studies were conducted at an angle of incidence of 70°. In-situ drying measurements under nitrogen were conducted for 15 min using a custom-made temperature-controlled glass flow cell [34]. Prior to entering the flow cell, the nitrogen was dried with a water absorbent and was led through an oxygen trap.

The CompleteEase 4.64 software (J.A. Woollam Co., Inc.) was used for spectroscopic data modeling. The optical properties of the silicon waver, and the native oxide silica layer on top of it, were taken from the software database. The thickness of the native silicon oxide was measured with spectroscopic ellipsometry and the obtained value of ~2 nm was fixed in further modeling. The wavelength range included in the fitting was 450–900 nm; in this range SPEEK is transparent and the Cauchy relation (Eq. 2) can be applied. All values reported for n and Δn correspond to the value at the wavelength of a helium–neon laser (632.8 nm). Depolarization that occurs due to thickness inhomogeneity was always carefully checked and fitted. In uniaxial modeling, the B parameters of the Cauchy equation for n xy and n z were coupled to ensure a physical realistic optical dispersion for SPEEK films. By coupling B xy and B z, a parallel trend of n xy and n z with wavelength is imposed and it is prevented that they cross.

Analysis of variance

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a confidence interval of 95 % was used to substantiate the significant differences in optical properties of SPEEK films formed under various conditions in spin-coating.

Results and discussion

Optical anisotropy

Figure 1 shows the ellipsometry spectra of a representative SPEEK film coated on a silicon substrate. Both the Psi and Delta spectra show a single oscillation with a position and amplitude that depends on the angle of incidence. These raw spectra are typical for SPEEK films of several hundred nanometers.

Fitting simultaneously the data obtained at the three angles, with an optical model that considers the material to be isotropic, yields a thickness of 324.4 nm (Fig. 1a). However, the MSE = 24.1, corresponding to this optical fit, is relatively high and not acceptable for a single film of low thickness. The high MSE value is mainly due to the skewness of the spectra that cannot be captured by the isotropic optical model. Fitting the data with a model that considers the material as uniaxial anisotropic results in an essentially unchanged thickness of 324.8 nm, but also in a significant reduction in MSE to a value of 6.8 (Fig. 1b). This significant decrease in MSE is considered to indicate that SPEEK films are anisotropic and Δn should be taken into account. Spectra obtained at different spots and after different sample rotations within the xy plane show no differences in Δn, implying that the SPEEK films exhibit no biaxial anisotropy and that the uniaxial Δn does not depend on the radial position on the wafer. The observed optical uniaxial anisotropy coincides with the observations of Reyna-Valencia et al. [27], who also determined Δn using an optical method and correlated the value of Δn to in-plane polymer chain orientations.

Here, we study several factors that may affect Δn and that are discussed in more detail below. The factors are the ambient relative humidity, the drying process, film formation via spin-coating and solution deposition, the use of volatile and non-volatile solvents, and the film conditioning under vacuum at 30 and 140 °C.

The effect of ambient relative humidity and subsequent drying

The dynamics of the changes in thickness and refractive indices of a representative SPEEK film, upon drying under nitrogen, are presented in Fig. 2a. In Fig. 2b, the black solid lines in the Psi and Delta spectra correspond to spectra obtained under ambient conditions (relative humidity RH = 50 %), prior to drying.

Thickness, refractive indices, and optical anisotropy of a SPEEK film (a) in the ambient and in dry N2, and (b) corresponding Psi and Delta data in the ambient (solid line) and at the end of the drying in N2 (dashed line). The film was spin-coated from a 5 wt% methanol solution at 2000 rpm and conditioned under vacuum at 30 °C for 48 h

The dashed lines correspond to the spectra obtained at the end of the drying process. The shift of oscillations toward lower wavelengths indicates a decrease in film thickness. The dynamics of the changes in thickness are representative for a desorption process involving both water diffusion and polymer relaxation. Initially, a sharp decrease in thickness is observed, due to diffusion limited removal of water. The subsequent slower reduction in thickness is related to polymer relaxation, which is a process with a much larger time constant. These observations are consistent with those of Potreck et al., who studied vapor sorption in SPEEK by mass uptake [35]. During desorption, the sample thickness decreased from an initial thickness of 333.8 to 284.7 nm at the end of the desorption process. Concurrently, the refractive indices of the film increased, indicating the removal of water and the densification of the polymer. Thus, the refractive index of the films is lower under ambient conditions as compared to under dry nitrogen. The presence of the sulfonic acid groups in SPEEK makes the material highly hydrophilic and causes the polymer films to swell and plasticize in the presence of water vapor [36, 37]. Because the refractive index of liquid water, 1.33, is lower than that of the polymer, the swollen films have a lower overall refractive index.

The removal of water also causes a significant increase in optical anisotropy, from 0.021 to the value of 0.047. This increase indicates that the stresses in the material become higher upon removal of water. The increase of optical anisotropy upon desorption of water coincides with the observations of Reyna-Valencia et al. [27], who have shown that upon repeated thermal cycling SPEEK films undergo orientations that result in increased and constant optical anisotropy. Moreover, they reported that the direction of the orientations was in-plane to the surface of the film. SPEEK films studied in our paper also exhibit orientations in the same direction. This is evidenced by the in-plane refractive n xy , which is always higher than the out-of-plane refractive index n z .

Thus, the results show that the ambient relative humidity has a direct impact on the thickness and optical anisotropy of SPEEK films. High affinity for the moisture results in swelling that in turn reduces the internal stresses. The effect becomes stronger with increasing relative humidity, as the sorption of water for SPEEK increases sharply above RH = 50 %. These observations imply that correct reporting of properties of SPEEK films requires specification of the relative humidity.

Additionally, the usage of SPEEK in processes, in which SPEEK films are alternately exposed to high humidity and dry conditions, results in repeated changes in material dimensions. Such behavior damages the membrane integrity, and reinforcement procedures are necessary [38].

Spin-coating with volatile solvents

Effect on thickness

Figure 3 shows the thicknesses as a function of the spin speed for several SPEEK films, prepared using either methanol or ethanol as a solvent. The measurements were performed in a humid ambient (RH = 50 %). At a spin speed of 1000 rpm, no layers could be obtained from 5 and 7 wt% solutions, due to poor substrate wettability at those conditions. The two distinct conditioning temperatures of 30 and 140 °C did not result in a difference in thickness.

The thicknesses of SPEEK films formed via spin-coating from methanol (circle and square) and ethanol (triangle and diamond) solutions of concentrations 3, 5, and 7 wt%, and conditioned under vacuum at 30 °C (circle and diamond) or 140 °C (square and diamond). Thickness values have been obtained from the center of the sample. Lines are to guide the eye

Methanol and ethanol are highly volatile solvents, commonly used for the fabrication of SPEEK membranes with a high degree sulfonation [39]. The viscosity of methanol (0.00059 Pa·s) is approximately half of that of ethanol (0.0012 Pa·s), and the vapor pressure of methanol (13.02 kPa) is almost twice as high as that of ethanol (5.95 kPa) [40, 41]. However, the data show no significant differences in the thickness of the films for the two solvents, despite the different solvent properties. This is in agreement with the scaling predicted by the model of Meyerhofer [42]. In this model, the film thinning process is considered to comprise two distinct and subsequent stages. In the first stage, the film thinning is only due to centrifugal-induced radial flow. In the second stage, the film thinning is only due to solvent evaporation. The resulting expression for the film thickness, h (nm), predicts the following scaling:

This expression contains the initial solution viscosity η 0 (Pa·s), the solvent vapor pressure ρ vap (kPa), and the spin speed ω (rpm). Based on this model, the expected difference in layer thickness for the two solvents is ~3 %. For the films obtained from the solutions with the low concentrations (3 and 5 wt%) and high spin speeds (2000–4000 rpm), the thickness scales with ω m, where m is an empirical scaling parameter. For both solvents and concentrations, the value of m varied between −0.44 and −0.5. This is again in good agreement with the scaling predicted by the expression of Meyerhofer [42, 43]. Also, the R-squared of the linear fits for calculation of the m is >0.998. For the higher concentration of 7 wt%, the scaling m is between −0.32 and −0.42 indicating that the simple model starts to fail for higher concentrations. The linear fits are also less appropriate, as is evidenced from the R 2 values (~0.98).

The presented thickness values are obtained from the centers of the samples. The thickness at the outer sides of the samples is typically a few percent less. This is due to the shear thinning viscosity of the polymer solutions and the radial dependence of the shear forces. The effect is more pronounced for more concentrated polymeric solutions. The results are in concurrence with the research of Gupta et al., who also reported shear thinning behavior for SPEEK solutions [44].

Effect on optical anisotropy and refractive index

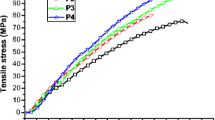

Figure 4a, b depict Δn and n xy of the films corresponding to Fig. 3 as a function of the spin speed, respectively. Only the data for the 3 and 5 wt% solutions are presented. For the 7 wt% solution inhomogeneous films (MSE >20) were obtained, resulting in a pronounced scattering of the Δn and n xy values.

Optical anisotropy, Δn (a) and in-plane refractive index, n xy (b) of SPEEK films formed via spin-coating from methanol (circle and square) or ethanol (triangle and diamond) of concentrations 3 and 5 wt%, and conditioned under vacuum at 30 °C (circle and triangle) or 140 °C (square and diamond). Open symbols indicate the ambient humid atmosphere (RH = 50 %) and closed symbols indicate the end of the drying process. The films obtained from 7 wt% are omitted due to high film inhomogeneity

The films were measured under humid ambient (RH = 50 %) and dry nitrogen atmosphere (RH = 0 %). The spin speed was varied in the range 1000–4000 rpm to investigate if shear forces during the spinning process affect the orientation of the polymer chains. In addition to the variable spin speed, the difference in viscosity of methanol and ethanol also implies distinct shear forces. For the data obtained at high spin speeds (≥2000 rpm) for 3 wt% solutions, no significant systematic dependence of Δn and n xy on the spin speed or solvent properties is observed. The analysis of variance confirms that no statistically relevant differences exist for those films. This indicates that the shear forces during the spinning process have no direct apparent effect on the stresses inside the final films, which is consistent with the absence of variations in Δn and n xy as a function of the position on the sample. For the lower spin speed of 1000 rpm, some changes, which are supported by ANOVA, in Δn and n xy can be observed. These can be possibly caused due to factors associated when applying very low spin speeds, such as poor surface wettability, increased film inhomogeneity, or changed drying rates [45, 46].

For the 5 wt%, there are statistical significant changes in the values of Δn and n xy . In particular, for 2000 rpm, the analysis of variance indicates that the values of Δn and n xy are significantly lower as compared to 3000–4000 rpm. The differences are possibly related to the decreased homogeneity of the films obtained at low spin speeds from more concentrated solutions. A lower homogeneity corresponds to more spatial randomness, and hence would be manifested by a lower Δn. To support this conclusion, films from 7 wt% solution were so inhomogeneous that their MSE exceed the value of 20.

The refractive index is strongly correlated with the density of the film, and the uniaxial anisotropy is related to internal stresses in the film originating from polymer chain orientations. For films from a 3 wt% solution, the refractive index and uniaxial anisotropy are not affected by the spinning conditions; the film thickness can be adjusted by the spin speed without affecting the other film properties. For a higher concentration, 5 wt%, films with lower and higher anisotropy and higher and lower density can be produced. For all SPEEK films, n xy is higher than n z . This signifies that the SPEEK polymer chains are preferentially oriented in-plane to the surface of the film. These orientations are not caused by the radial flow and forces pertaining to the spin-coating process, and are not affected by the physical properties of the solvent used. Furthermore, the preferred chain orientations persist when thermal conditioning is performed at 140 °C instead of 30 °C. 140 °C is apparently too far from the glass transition (~200 °C) [47] to induce structural changes in the polymer films. Both temperatures are sufficient to ensure removal of any residual methanol and ethanol. The internal stresses in the films are affected by the presence of water. Water has high affinity for the charged sulfonic groups and will readily sorb into the material. The presence of water results in plasticization: the polymer chains become more mobile due to the presence of the water. The enhanced mobility, combined with the dilation of the film in the z-direction to accommodate the water sorption, causes relaxations of the polymer chains with less preferred in-plane orientations.

Solution deposition with a volatile and a non-volatile solvent

In the previous section, the plasticizing effect of water vapor has been discussed. Water sorption reduces the internal stresses in SPEEK membranes, and, therefore, it also reduces the optical anisotropy. A similar effect can be expected to occur for other penetrants, especially for those that are able to dissolve SPEEK. Hence, here we study, the optical properties of films that have been made using N-methylpyrrolidinone as a solvent. NMP dissolves SPEEK with a low degree of sulfonation [7], whereas methanol and ethanol are typically used to dissolve SPEEK with a high degree of sulfonation. The poor wettability of wafers by NMP complicates controlled spin-coating, which can be circumvented using the solution deposition method, i.e., spin-coating at zero spin speed.

In Table 1, the representative data are presented for SPEEK films formed via solution deposition technique, using NMP or the more volatile methanol as solvent, and measured at RH 20–30 %. The film thicknesses could not be easily controlled but they are in the range of the thicknesses from Fig. 3. The focus is put on optical properties.

Visual observations indicate that film formation occurs in approximately 1 min in the case of methanol, and in several hours in the case of NMP. Before conditioning under vacuum at 30 °C, methanol-derived films were characterized 30 min after formation, and NMP-derived films 3 days after formation. The refractive index values n xy of the NMP- and methanol-derived films are much lower than those of films corresponding to Fig. 4b (>1.63), indicating that the solvents are still present in the films. The refractive indices of methanol (n = 1.32) and NMP (n = 1.47) are much lower than that of the polymer, causing the effective refractive index to be reduced when the solvents are present in the films. For the methanol-derived films, n xy = 1.58 is higher as compared to n xy = 1.51 for the NMP-derived films. This result is consistent with the much faster evaporation of methanol as compared to NMP. The low refractive index in the case of the NMP-derived films is actually very close to the value of pure NMP. This indicates that a large concentration of NMP is still present in the film, even at 3 days after film formation. This is substantiated by the absence of anisotropy in the NMP swollen films; Δn = 0 and the isotropic and anisotropic optical models give similar MSE values. In contrast, significant anisotropy is observed for films derived from the methanol solution; Δn > 0.01 and lower MSE for the anisotropic optical model.

Subsequently, the optical properties have been analyzed after the films have been conditioned under vacuum at 30 °C. The values for n xy and Δn of methanol-derived films are comparable with those of films formed via spin-coating (Fig. 4). During conditioning, the methanol is completely removed, causing an increase in density (n xy ) and internal stresses (Δn). Fitting with the anisotropic, instead of the isotropic optical model, results in a significant reduction of the MSE. NMP-derived films show a small positive value for Δn and a strongly increased n xy . This indicates significant but not complete removal of the NMP.

Finally, the films have been characterized after conditioning under vacuum at 140 °C. For methanol-derived films the solvent is completely removed, similar to the conditioning at 30 °C. Because the temperature of 140 °C is too far from the glass transition temperature, no structural rearrangements of the polymer occur. Consequently, the temperature of the conditioning step does not significantly affect the optical properties of the methanol-derived films, and the corresponding MSE.

For the NMP-derived films, the removal of NMP at 140 °C is far more effective than at 30 °C. This is manifested by an increase in n xy as well as in Δn. Still, for various spots on the sample a lower anisotropy is observed, indicating that NMP is not removed completely at 140 °C. The difficult removal of NMP is due to its high boiling point, but also due to its favorable interactions with sulfonic acid groups [22, 48].

Overall, the results indicate that sorption of organic solvents can reduce the internal stresses in thin SPEEK films. Notably, the density of, and internal stresses in, thin SPEEK films are similar when comparing films prepared by spin-coating and solvent deposition. This further substantiates that stresses in the material are not affected by the shear forces induced during spin-coating, but are inherent to thin films of this sulfonated polymer. This conclusion is in agreement with literature. It is known that molecular orientations can originate from the self-alignment of polymeric chains, due to specific chemical properties (e.g., polarity) that cause interactions between molecules [28, 49]. These interactions drive polymeric chains to align in a specific manner. For SPEEK, the specific orientations are due to polar sulfonic acid groups. This is in line with the recent research of Krishnan et al., who found sulfonated polyimide thin films to be inherently anisotropic with the orientation along the in-plane direction [50].

Analysis of the anisotropy of the SPEEK samples that have been aged for 1 year shows that slow polymer relaxations do not lead to disappearance of the anisotropy in the thin films. The slow relaxations do affect the homogeneity of the films. Fresh films derived from a 7 wt% solution cannot be accurately modeled (MSE >20), but after 372 days of aging the MSE is significantly decreased (<10). The aged 7 wt% films have values for Δn that are of the same order as these of films derived from 5 wt% solutions. The inherent self-alignment orientations can only be irreversibly affected by chemical modifications [51], and, as we have shown, reversibly by plasticizing agents.

Conclusions

Molecular orientations in SPEEK thin films have been investigated using spectroscopic ellipsometry. The thin films exhibit a uniaxial optical anisotropy that implies preferred orientations of the polymer chains, which are for SPEEK in the in-plane direction. In turn, the preferred molecular orientations lead to internal stresses in the films. The molecular orientations do not originate from film formation conditions: different solvents, different film formation methods, and different hydrodynamic forces acting on the polymer chains during film formation, essentially, do not change the extent of anisotropy. The internal stresses, coupled with the density, can be varied to some extent when solutions with higher polymer concentrations are used for the spin-coating synthesis. The presence of molecular orientations in thin SPEEK films are inherent to this polymer, and are not removed by elevated temperatures. The associated internal stresses can be released by the presence of water or organic solvents. Subsequent removal of such penetrants is accompanied by a full reestablishment of the internal stresses.

References

Winardi S, Raghu SC, Oo MO, Yan QY, Wai N, Lim TM, Skyllas-Kazacos M (2014) Sulfonated poly (ether ether ketone)-based proton exchange membranes for vanadium redox battery applications. J Membr Sci 450:313–322

Li Z, Dai W, Yu L, Liu L, Xi J, Qiu X, Chen L (2014) Properties investigation of sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone)/polyacrylonitrile acid-base blend membrane for vanadium redox flow battery application. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 6(21):18885–18893

Hande VR, Rath SK, Rao S, Patri M (2011) Cross-linked sulfonated poly (ether ether ketone) (SPEEK)/reactive organoclay nanocomposite proton exchange membranes (PEM). J Membr Sci 372(1–2):40–48

Xue S, Yin G (2006) Methanol permeability in sulfonated poly(etheretherketone) membranes: a comparison with Nafion membranes. Eur Polym J 42(4):776–785

Basile A, Paturzo L, Iulianelli A, Gatto I, Passalacqua E (2006) Sulfonated PEEK-WC membranes for proton-exchange membrane fuel cell: effect of the increasing level of sulfonation on electrochemical performances. J Membr Sci 281(1–2):377–385

Gil M, Ji X, Li X, Na H, Hampsey JE, Lu Y (2004) Direct synthesis of sulfonated aromatic poly(ether ether ketone) proton exchange membranes for fuel cell applications. J Membr Sci 234(1–2):75–81

Li L, Zhang J, Wang Y (2003) Sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) membranes for direct methanol fuel cell. J Membr Sci 226(1–2):159–167

Kreuer KD (1997) On the development of proton conducting materials for technological applications. Solid State Ionics 97(1–4):1–15

Kattan Readi OM, Gironès M, Nijmeijer K (2013) Separation of complex mixtures of amino acids for biorefinery applications using electrodialysis. J Membr Sci 429:338–348

Güler E, Elizen R, Vermaas DA, Saakes M, Nijmeijer K (2013) Performance-determining membrane properties in reverse electrodialysis. J Membr Sci 446:266–276

Giuseppin MLF, Smits PJ, Hofland GW (2012) Subcritical gas assisted drying of biopolymer material. Patent US 20120316331 A1

Dalwani M, Bargeman G, Hosseiny SS, Boerrigter M, Wessling M, Benes NE (2011) Sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) based composite membranes for nanofiltration of acidic and alkaline media. J Membr Sci 381(1–2):81–89

Sijbesma H, Nymeijer K, van Marwijk R, Heijboer R, Potreck J, Wessling M (2008) Flue gas dehydration using polymer membranes. J Membr Sci 313(1–2):263–276

Huang RYM, Shao P, Feng X, Burns CM (2001) Pervaporation separation of water/isopropanol mixture using sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) (SPEEK) membranes: transport mechanism and separation performance. J Membr Sci 192(1–2):115–127

Jia L, Xu X, Zhang H, Xu J (1996) Sulfonation of polyetheretherketone and its effects on permeation behavior to nitrogen and water vapor. J Appl Polym Sci 60(8):1231–1237

Khan AL, Klaysom C, Gahlaut A, Li X, Vankelecom IFJ (2012) SPEEK and functionalized mesoporous MCM-41 mixed matrix membranes for CO 2 separations. J Mater Chem 22(37):20057–20064

Khan AL, Li X, Vankelecom IFJ (2011) Mixed-gas CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 separation with sulfonated PEEK membranes. J Membr Sci 372(1–2):87–96

Khan AL, Li X, Vankelecom IFJ (2011) SPEEK/Matrimid blend membranes for CO2 separation. J Membr Sci 380(1–2):55–62

Luo Y, Huo R, Jin X, Karasz FE (1995) Thermal degradation of sulfonated poly(aryl ether ether ketone). J Anal Appl Pyrol 34(2):229–242

Knauth P, Hou H, Bloch E, Sgreccia E, Di Vona ML (2011) Thermogravimetric analysis of SPEEK membranes: thermal stability, degree of sulfonation and cross-linking reaction. J Anal Appl Pyrol 92(2):361–365

Jin X, Bishop MT, Ellis TS, Karasz FE (1985) Sulfonated poly(aryl ether ketone). Br Polym J 17(1):4–10

Mikhailenko SD, Wang K, Kaliaguine S, Xing P, Robertson GP, Guiver MD (2004) Proton conducting membranes based on cross-linked sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) (SPEEK). J Membr Sci 233(1–2):93–99

Hou H, Maranesi B, Chailan JF, Khadhraoui M, Polini R, Di Vona ML, Knauth P (2012) Crosslinked SPEEK membranes: mechanical, thermal, and hydrothermal properties. J Mater Res 27(15):1950–1957

Reiter G (2013) Probing properties of polymers in thin films via dewetting. In: Kanaya T (ed) Glass transition, dynamics and heterogeneity of polymer thin films, vol 252. Springer, Berlin, pp 29–63

Tsui OKC, Wang YJ, Lee FK, Lam CH, Yang Z (2008) Equilibrium pathway of spin-coated polymer films. Macromolecules 41(4):1465–1468

Huang Y, Paul DR (2004) Physical aging of thin glassy polymer films monitored by gas permeability. Polymer 45(25):8377–8393

Reyna-Valencia A, Kaliaguine S, Bousmina M (2006) Structural and mechanical characterization of poly(ether ether ketone) (PEEK) and sulfonated PEEK films: effects of thermal history, sulfonation, and preparation conditions. J Appl Polym Sci 99(3):756–774

Ward IM (1997) Structure and properties of oriented polymers, 2nd edn. Springer, The Netherlands

Fujiwara H (2007) Spectroscopic ellipsometry., Principles of spectroscopic ellipsometry. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 81–146

Woollam JA, John B, Herzinger C, Hilfiker J, Synowicki R, Bungay C (1999) Overview of variable angle spectroscopic ellipsometry (vase). Part I: basic theory and typical applications. SPIE Proc CR72 1:3–28

Askadski AA (1996) Physical properties of polymers. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Shibuya N, Porter RS (1992) Kinetics of PEEK sulfonation in concentrated sulfuric acid. Macromolecules 25(24):6495–6499

Zaidi SMJ, Mikhailenko SD, Robertson GP, Guiver MD, Kaliaguine S (2000) Proton conducting composite membranes from polyether ether ketone and heteropolyacids for fuel cell applications. J Membr Sci 173(1):17–34

Ogieglo W, Wormeester H, Wessling M, Benes NE (2013) Temperature-induced transition of the diffusion mechanism of n-hexane in ultra-thin polystyrene films, resolved by in situ spectroscopic ellipsometry. Polymer (UK) 54(1):341–348

Potreck J, Uyar F, Sijbesma H, Nijmeijer K, Stamatialis D, Wessling M (2009) Sorption induced relaxations during water diffusion in S-PEEK. Phys Chem Chem Phys 11(2):298–308

Hara M, Sauer JA (1994) Mechanical properties of ionomers. J Macromol Sci Rev Macromol Chem Phys C34(3):325–373

Reyna-Valencia A, Kaliaguine S, Bousmina M (2005) Tensile mechanical properties of sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) (SPEEK) and BPO4/SPEEK membranes. J Appl Polym Sci 98(6):2380–2393

Oh K-H, Lee D, Choo M-J, Park KH, Jeon S, Hong SH, Park J-K, Choi JW (2014) Enhanced durability of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells by functionalized 2D boron nitride nanoflakes. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 6(10):7751–7758

Yen S-PS, Narayanan Sekharipuram R., Halpert Gerald, Graham Eva, Yavrouian, Andre (1998) Polymer material for electrolytic membranes in fuel cells. Patent US 5795496

Smallwood IM (1996) Ethanol. Handbook of organic solvent properties. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp 65–67

Smallwood IM (1996) Methanol. Handbook of organic solvent properties. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp 61–63

Meyerhofer D (1978) Characteristics of resist films produced by spinning. J Appl Phys 49(7):3993–3997

Hall DB, Underhill P, Torkelson JM (1998) Spin coating of thin and ultrathin polymer films. Polym Eng Sci 38(12):2039–2045

Gupta M, Deshpande AP, Kumar PBS (2014) Rheology of concentrated sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) solutions. J Appl Poly Sci 131(7). doi:10.1002/app.40044

Bornside DE, Macosko CW, Scriven LE (1987) Modeling of spin coating. J Imaging Technol 13(4):122–130

Zhu Z, Lowes J, Berron J, Smith B, Sullivan D (2014) Spin-coating defect theory and experiments. ECS Trans 60(1):293–302

Carbone A, Pedicini R, Portale G, Longo A, D’Ilario L, Passalacqua E (2006) Sulphonated poly(ether ether ketone) membranes for fuel cell application: thermal and structural characterisation. J Power Sour 163(1):18–26

Jun M-S, Choi Y-W, Kim J-D (2012) Solvent casting effects of sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) for Polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell. J Membr Sci 396:32–37

Shimo T, Nagasawa M (1992) Stress and birefringence relaxations of noncrystalline linear polymer. Macromolecules 25(19):5026–5029

Krishnan K, Iwatsuki H, Hara M, Nagano S, Nagao Y (2014) Proton conductivity enhancement in oriented, sulfonated polyimide thin films. J Mater Chem A 2(19):6895–6903

Zhang Z, Liu I, Xiao G, Grover CP (2004) Novel approach to reducing stress-caused birefringence in polymers. J Mater Sci 39(4):1415–1417. doi:10.1023/B:JMSC.0000013907.19650.f7

Acknowledgements

This work was performed in the cooperation framework of Wetsus, Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Water Technology (www.wetsus.nl). Wetsus is co-funded by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment, the European Union Regional Development Fund, the Province of Fryslân, and the Northern Netherlands Provinces. The authors would like to thank the participants of the research theme “Dehydration” for the fruitful discussions and their financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Koziara, B.T., Nijmeijer, K. & Benes, N.E. Optical anisotropy, molecular orientations, and internal stresses in thin sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) films. J Mater Sci 50, 3031–3040 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-015-8844-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-015-8844-0