Abstract

Although a great deal of attention has been paid to entrepreneurship education, only a few studies have analysed the impact of extra-curricular entrepreneurial activities on students’ entrepreneurial intention. The aim of this study is to fill this gap by exploring the role played by Student-Led Entrepreneurial Organizations (SLEOs) in shaping the entrepreneurial intention of their members. The analysis is based on a survey that was conducted in 2016 by one of the largest SLEOs in the world: the Junior Enterprises Europe (JEE). The main result of the empirical analysis is that the more time students spent on JEE and the higher the number of events students attended, the greater their entrepreneurial intention was. It has been found that other important drivers also increase students’ entrepreneurial intention, that is, the Science and Technology field of study and the knowledge of more than two foreign languages. These results confirm that SLEOs are able to foster students’ entrepreneurial intention. The findings provide several theoretical, practical and public policy implications. SLEOs are encouraged to enhance their visibility and lobbying potential in order to be recognized more as drivers of student entrepreneurship. In addition, it is advisable for universities and policy makers to support SLEOs by fostering their interactions with other actors operating in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, who promote entrepreneurship and technology transfer activities. Lastly, this paper advises policy makers to assist SLEOs’ activities inside and outside the university context.

Resumen

Aunque se ha prestado mucha atención a la educación emprendedora, pocos estudios han analizado el impacto de las actividades emprendedoras extracurriculares en la intención de emprender de los estudiantes. El objetivo de este estudio es llenar este vacío en la literatura mediante la exploración del papel que desempeñan las Organizaciones Empresariales Dirigidas por Estudiantes (Student-Led Entrepreneurial Organizations SLEOs por sus siglas en ingles) en la configuración de la intención emprendedora de sus miembros. El análisis se basa en una encuesta que fue realizada en 2016 por uno de los SLEO más importantes a nivel mundial: Junior Enterprises Europe (JEE). El resultado principal del análisis empírico es que cuanto más tiempo dedicaban los estudiantes a JEE y mayor era el número de eventos a los que asistían, mayor era su intención emprendedora. Se ha encontrado que otros factores importantes también aumentan el propósito emprendedor de los estudiantes, es decir, el campo de estudio de la ciencia y la tecnología y el conocimiento de más de dos idiomas extranjeros. Estos resultados confirman que los SLEO pueden fomentar el propósito emprendedor de los estudiantes. Los resultados proporcionan varias implicaciones teóricas, prácticas y de políticas públicas. Se anima a los SLEO a mejorar su visibilidad y su potencial de cabildeo para ser más reconocidos como impulsores del espíritu emprendedor de los estudiantes. Además, es recomendable que las universidades y los formuladores de políticas apoyen a las SLEO fomentando sus interacciones con otros actores que operan en el ecosistema emprendedor, quienes promueven el emprendimiento y las actividades de transferencia de tecnología. Por último, este documento aconseja a los responsables de las políticas que ayuden a las actividades de los SLEO dentro y fuera del contexto universitario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Contribution: Although numerous works have studied the role played by specific entrepreneurship education programs in influencing students’ entrepreneurial intention, this paper is the first to examine the factors that are associated with students’ entrepreneurial intent in the context of Student-Led Entrepreneurial Organizations (SLEOs).

Research Question/Purpose: The purpose of this paper has been to explore the role played by SLEOs in shaping the entrepreneurial intention of their members from a double perspective: individual-specific and organizational-specific.

Information/data: The data comes from a survey to one of the largest SLEOs in the world, the Junior Enterprises Europe (JEE).

Methodology: The study has empirically investigated the factors that affect students’ entrepreneurial intention by conducting several regression analyses.

Results/findings: The main result of the empirical analysis is that the more time students spent in JEE and the higher the number of events students attended, the greater their entrepreneurial intention was. This result suggests that SLEOs have a positive and statistically significant impact on the entrepreneurial intention of their members and, as such, they constitute an important component of the entrepreneurial university ecosystem that is able to foster an entrepreneurial culture. Other important drivers that can increase students’ entrepreneurial intention are being a student in the Science and Technology field and the knowledge of more than two foreign languages.

Limitations: The main limitations of this work are that the survey was only addressed to the members of one SLEO (albeit one of the largest) and the lack of a control sample.

Theoretical implications and recommendations: The findings show that SLEOs play an important role in shaping the willingness of students to become entrepreneurs. SLEOs are a relevant component of the entrepreneurial university ecosystem and actively help promote an entrepreneurial culture. Therefore, future studies on entrepreneurship should consider SLEOs as non-trivial stakeholders of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and incorporate the experiences of SLEOs in the analysis of entrepreneurial intention and abilities. The results also indicate that, in addition to experience in SLEOs, a student’s individual-specific attributes and curriculum are also important factors that help shape the willingness of students to become entrepreneurs.

Managerial and practical implications and recommendations: This paper has practical implications for SLEOs, universities and policy makers. SLEOs are encouraged to enhance their visibility and lobbying power in order to be more recognized as drivers of student entrepreneurship. It is also suggested that universities should support and help students connect with SLEOs. Furthermore, universities could include SLEOs in consultations and promote their interaction with other actors engaged in entrepreneurship and technology transfer activities. Finally, policy makers could sustain SLEOs financially and foster their role in the entrepreneurial ecosystem with the aim of increasing society’s entrepreneurial culture.

Public policy implications and recommendations: This paper suggests that SLEOs are key agents in the development of an entrepreneurial culture among young people and the study of the role they play in shaping the entrepreneurial intention of their members is crucial in evaluating if there is a case for public policy intervention to stimulate their activity. This paper advises policy makers to assist SLEOs’ activities inside and outside the university context. Policy makers might need to design diversified policy initiatives and support measures to fit distinct entrepreneurial environments and to respond to different endorsements by universities.

Recommendations for future research: Future studies could explore which types of start-ups have been founded by SLEO associates and how the founders evaluate their experience in the SLEO. Moreover, it could be interesting to focus on students enrolled in SLEO not only in Europe but also outside Europe (such as in the USA, China, or in developing countries) in order to understand whether and how the impact of SLEOs changes across countries and to measure how the cultural differences of different countries impact entrepreneurial intention. Finally, since SLEOs are important actors in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, they should be included in future studies on the entrepreneurial culture and ecosystem of universities.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, the importance of entrepreneurship for economic growth has been widely recognized (Powers and McDougall 2005; Van Stel et al. 2005; Van Praag and Versloot 2007; Braunerhjelm et al. 2010; Nabi and Liñán 2013; GEM 2017). Recently, it has also been suggested that entrepreneurship helps enlighten people and encourage their personal growth (EC 2006; EC 2012; Farny et al. 2016). A report from the European Commission in 2012 has shown, for instance, that entrepreneurial attitudes are useful for all individuals in their daily lives and working activities.

Governments are currently fostering the creation and promotion of an entrepreneurial culture and ecosystem (Cavallo et al. 2020) by involving universities in order to enhance students’ entrepreneurial abilities and intention (Lewis and Llewellyn 2004; O’Connor 2013; Wright et al. 2017; Siivonen et al. 2019; Barbini et al. 2020). Accordingly, a remarkable expansion in the number of programs devoted to entrepreneurship education, aimed at introducing a cultural change of entrepreneurship, to all levels of education, has been realized throughout the world (Katz 2003; Kuratko 2005; EC 2012; Blenker et al. 2012; Fretschner and Weber 2013; Martin et al. 2013; O’Connor 2013).

Entrepreneurship education represents a significant policy intervention, since it improves entrepreneurial abilities (EC 2006), has an impact on students’ entrepreneurial intention (Peterman and Kennedy 2003; Souitaris et al. 2007; Pruett et al. 2009; Engle et al. 2010; Sánchez 2013), produces benefits to students’ employability skills (Etzkowitz et al. 2000) and, more generally, propels economic growth (Abreu and Grinevich 2013). Therefore, entrepreneurship education is a valuable instrument that affects students as members of society as a whole, and not (just) as scholars in the classroom (Farny et al. 2016). There are now clear indications that universities are improving their curricular and extra-curricular entrepreneurial activities (Hannon 2007; Souitaris et al. 2007; Wilson et al. 2007; Arranz et al. 2017; Varano et al. 2019) in order to encourage students to become enterprising (Pittaway and Cope 2007; Sansone et al. 2019).

As an indirect result of all these activities to support entrepreneurship, Student-Led Entrepreneurial Organizations (henceforth SLEOs) have started to emerge around the world. These organizations leverage on students’ willingness and desire to carry out practical and real-world experiences of entrepreneurship, while continuing to study at university (Siivonen et al. 2019). Their aim is in fact to enhance the entrepreneurial abilities of their members through learning by doing and experiential learning. Some important SLEOs are the Junior Enterprises Europe (JEE), Enactus, Collegiate Entrepreneurs Organization (CEO) and the National Association of College and University Entrepreneurs (NACUE) (Pittaway et al. 2011, 2015; Preedy and Jones 2017).

SLEOs allow students to attend entrepreneurship events and workshops, to network, to work in multidisciplinary and international teams and to share ideas. All these activities promote an entrepreneurial environment and culture that is deemed to foster entrepreneurship (Pittaway et al. 2015; Wright et al. 2017). Today, SLEOs have links with several universities, both in Europe and in the USA (Pittaway et al. 2011; Rae et al. 2012; Preedy and Jones 2015, 2017) and are increasingly becoming an important component of the entrepreneurial university ecosystem (Siegel and Wright 2015; Siivonen et al. 2019). In addition, the number of SLEOs is constantly growing (some SLEOs have recently been created, e.g. Altoes and the London Business School Entrepreneurship Club, among others).

Even though growing attention toward entrepreneurship education has recently emerged, few studies have been devoted to the analysis of extra-curricular entrepreneurial activities and to their role in fostering entrepreneurial abilities and entrepreneurial intention (Pittaway et al. 2011, 2015; Padilla-Angulo 2017; Preedy and Jones 2017). Several studies have discussed how entrepreneurship education, the content of the entrepreneurship courses, the entrepreneurship teaching model and the entrepreneurial culture and ecosystem have an impact on entrepreneurial intention and abilities (see Nabi et al. 2017 for a recent literature review). However, only a limited number of works have analysed to what extent extra-curricular entrepreneurial activities affect students’ entrepreneurial intention (Pittaway et al. 2011, 2015; Padilla-Angulo 2017; Preedy and Jones 2017).

The scarcity of research on how entrepreneurial attitudes are shaped by the participation of students in extra-curricular entrepreneurial activities calls for more evidence. The present study aims at addressing this gap, by examining the factors that are associated with students’ entrepreneurial intention in the context of SLEOs.

This work adds to the extant literature in two main ways. First, it augments and complements the current research on SLEOs by examining the domain of entrepreneurial intention formation, which has surprisingly received very little attention so far. Although there is still a need for a greater understanding of the factors that can shape the willingness of students to become entrepreneurs (Wright et al. 2017; Siivonen et al. 2019; Barbini et al. 2020), there is also considerable debate surrounding which factors affect their entrepreneurial intention the most. Moreover, the role played by SLEOs in this process has not been taken into consideration so far. By doing this, the study also discusses how SLEOs help foster an entrepreneurial culture and ecosystem. Second, the present study examines what affects students’ entrepreneurial intention from a double perspective: individual-specific and organizational-specific. A more comprehensive framework for the analysis of students’ entrepreneurial intention is thus provided, as the human capital–specific traits of SLEO members (e.g. gender, age, educational background, international openness) have been combined with specific organizational ones (e.g. the members’ experience within the SLEO). More specifically, our investigation formalizes the effect of a number of aspects that influence the formation of entrepreneurial intention, at both the individual and organization level: the time spent in extra-curricular entrepreneurial activities, the number of events attended within SLEOs, as well as the knowledge of languages and the field of study of the students.

The study empirically has investigated the factors that affect students’ entrepreneurial intention by conducting a multivariate explorative analysis of one of the largest SLEOs in the world, JEE. It has analysed the responses of a survey that was administered to JEE associates in 2016, which resulted in a total of 261 responses. The findings indicate that the more time students spent in JEE and the higher the number of events students attended, the greater their entrepreneurial intention was. This result suggests that SLEOs have a positive and statistically significant impact on the entrepreneurial intention of their members and, as such, they constitute an important component of the entrepreneurial university ecosystem that is able to foster an entrepreneurial culture. Additionally, it has been found that when students speak more than two foreign languages, and their study field is Science and Technology, there is a higher probability of developing entrepreneurial intention. This indicates that individual-specific traits are also relevant factors that shape the willingness of students to become entrepreneurs.

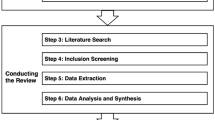

The paper is organized as follows. The “Background” section summarizes the extant research on students’ entrepreneurial intention and abilities, and the role played by SLEOs in the formation of entrepreneurial intention. The “An example of SLEO: JEE” section describes the activities of JEE. The “Research design” section presents the empirical results, which are based on the survey sent to the JEE associates in 2016. The “Conclusion” section discusses the theoretical and practical implications of the results, the limitations and avenues for future research.

Background

Why is it important to stimulate students’ entrepreneurial intention and abilities?

Policy makers believe that there is a close relationship between a country’s economic development and innovation and its entrepreneurial activities (Sánchez 2013). In line with this, several studies (e.g. Van Praag and Versloot 2007; GEM 2017) have shown a positive impact of entrepreneurship on a country’s economic growth and innovation. The European Commission has recently recognized entrepreneurship as one of the key competences that all individuals need (EU 2006). In 2016, the European Commission also developed the “Entrepreneurship Competence framework” (EntreComp) with the aim to raise consensus among all stakeholders and to establish a bridge between the worlds of education and work (Bacigalupo et al. 2016; Fiore et al. 2019). Therefore, policy makers are fostering the development of an entrepreneurial culture (Lewis and Llewellyn 2004; O’Connor 2013) in order to increase entrepreneurial activities (Lado and Vozikis 1996; Cavallo et al. 2020). Entrepreneurial intention and abilities are fundamental in this process (Lee et al. 2011; Saeed et al. 2015). As suggested in a recent longitudinal study conducted by Kautonen et al. (2015), entrepreneurial intention predicts entrepreneurial action. In addition, entrepreneurial abilities are necessary for a knowledge-based society (Bacigalupo et al. 2016).

The literature has shown several factors than can affect students’ entrepreneurial intention. As suggested in a recent study conducted by Johnstone et al. (2018), language ability is an important resource for entrepreneurship. Similarly, the experience of students abroad can positively influence their entrepreneurial intention (Brandenburg et al. 2014; Fayolle and Gailly 2015) as a result of an enlargement of their network and an enhancement of their soft skills. Prior family business exposure is another factor that has been associated with the formation of entrepreneurial intent (Carr and Sequeira 2007). Additionally, the age and gender of students can affect entrepreneurial risk taking (Barber 2015) and, ultimately, entrepreneurial intention (e.g. Shinnar et al. 2012; Barber 2015; Minola et al. 2016). It has also been found that the lack of a steady job stimulates people to become entrepreneurs (Audretsch and Thurik 2001; GEM 2002), thus pointing to the importance of the welfare of a country.

One of the best ways of fostering entrepreneurial abilities and intention is to establish a favourable institutional culture for entrepreneurship (Wang and Verzat 2011; Arranz et al. 2017). In fact, several studies have discussed the importance of the “hidden curriculum” in shaping students’ entrepreneurial spirits (e.g. Souitaris et al. 2007; Shinnar et al. 2009; Farny et al. 2016). This “hidden curriculum” reflects more than just lessons learnt inside the class as it also includes the beliefs and unspoken values about entrepreneurship that are inherent to society, as well as the knowledge that students learn from their engagement with a wider society (Farny et al. 2016). For instance, the idea of entrepreneurs as heroes of society (Anderson and Warren 2011; Farny et al. 2016), the role of social media entrepreneurs or star entrepreneurs (Swail et al. 2014; Obschonka et al. 2017) and the perceived opportunities of becoming an entrepreneur (Lüthje and Franke 2003; Giacomin et al. 2011; Maresch et al. 2016) are just some of the societal elements that are able to influence aspiring entrepreneurs.

In this context, entrepreneurship is promoted as a desirable and meaningful action in today’s society, thanks to the diffusion of entrepreneurship courses (Farny et al. 2016). Entrepreneurship education is essential to stimulate entrepreneurial intention and abilities (e.g. Rae et al. 2012; O’Connor 2013). Several studies have found that entrepreneurship education has a positive impact on students’ entrepreneurial intention (Peterman and Kennedy 2003; Souitaris et al. 2007; Pruett et al. 2009; Engle et al. 2010; Lanero et al. 2011; Sánchez 2013; Bae et al. 2014), while only a few studies have contradicted this view (Raffo et al. 2000; Oosterbeek et al. 2010). However, since entrepreneurship courses are offered in different fields of study and/or at different educational levels, their impact on students’ entrepreneurial attitudes and intention can vary (Wang and Wong 2004; Wang and Verzat 2011; Maresch et al. 2016). A number of studies (Schwarz et al. 2009; Wang and Verzat 2011; Edelman et al. 2016; Morris et al. 2017) have suggested that business students generally present a higher entrepreneurial intention than their peers enrolled in other programs. Nevertheless, entrepreneurship education also seems to have a positive impact on technical students (Souitaris et al. 2007; Criaco et al. 2017; Elia et al. 2017). In fact, Maresch et al. (2016) found that entrepreneurship education is effective for students enrolled in both Science and Engineering and Business Studies, even though subjective norms have been found to negatively influence the entrepreneurial intention of Science and Engineering students.

The need for further research on the impact of entrepreneurship education on students in different contexts was advanced by Vanevenhoven (2013) and Fiore et al. (2019). Entrepreneurship education can imply different teaching methods (Nabi et al. 2017; Sansone et al. 2019) and contents (which should be more theory or practice oriented). Mwasalwiba (2010) found twenty-six different teaching methods of entrepreneurship. It has been pointed out that entrepreneurship courses are generally too theoretical (Raffo et al. 2000; Feldman 2001; Rasmussen and Sørheim 2006; do Paço et al. 2011). However, it is well known that entrepreneurship cannot be learned from theory alone (Cope and Watts 2000; Klofsten 2000; Feldman 2001; Fiet 2001; Pittaway et al. 2011; Kassean et al. 2015; Sansone et al. 2019). In this context, it is necessary to encourage critical and reflective approaches to entrepreneurship education (Siegel and Wright 2015). In fact, in order to develop an entrepreneurial mindset, students need to have some practical experience during their studies (Feldman 2001; Todorovic 2004; Rasmussen and Sørheim 2006; Pittaway and Cope 2007; Pittaway et al. 2011, 2015; Bacigalupo et al. 2016; Preedy and Jones 2017; Fiore et al. 2019). When students participate in hands-on experiential learning, they gain the skills and intention required to become entrepreneurs (Corbett 2005; Clark et al. 2008; Fiore et al. 2019). In fact, project-based learning provides real-world experience that stimulates students’ entrepreneurial abilities by enhancing their problem-solving and proactive skills (Pittaway and Cope 2007).

Apart from curricular entrepreneurship courses, which help shape entrepreneurial intention, students can take part in several extra-curricular activities during their academic life. Rae et al. (2012) suggested that a change should be made on how students learn, with emphasis on action learning and experiential activities. Recent research has shown that these activities are important, not only for career development and employability, but also for entrepreneurship (Pittaway et al. 2015). Arranz et al. (2017) found a mixed impact of extra-curricular activities on entrepreneurial intention, but they also showed that extra-curricular activities help students transform intention into projects. Rubin et al. (2002) showed that students involved into extra-curricular activities develop stronger social skills, compared to those who do not participate in such activities. In fact, taking part to extra-curricular activities helps students build their own network and develop specific skills, which ultimately affect their propensity to start and run an entrepreneurial business. According to prior literature (Birley 1985; Zimmer and Aldrich 1987; Johanson and Vahlne 2003; Arenius 2005; Zahra et al. 2005; Kiss and Danis 2010; Sandhu et al. 2011; Bonaccorsi et al. 2014; Wright et al. 2017), networking is a key component for launching and making new businesses grow. For instance, network relations provide support for entrepreneurial risk-taking (Brüderl and Preisendörfer 1998), enhance perseverance in running a start-up process (Gimeno et al. 1997; Ghezzi and Cavallo, 2020) and is one of the highest barriers to entrepreneurship (Sandhu et al. 2011). However, there are still very few studies on the impact of extra-curricular entrepreneurial activities on entrepreneurial intention (Pittaway et al. 2011, 2015; Padilla-Angulo 2017; Preedy and Jones 2017).

The formation of entrepreneurial intention: the role of SLEOs

The emergence of SLEOs in Europe dates back to the end of the 1960s, when the first SLEO was founded in France (Junior École Supérieure des Sciences Économiques et Commerciales—ESSEC). SLEOs are organizations that are created and managed by students, with the explicit aim of providing a learning by doing experience to those students who are interested in entrepreneurship. SLEOs bring together students from different countries, different fields of study and different educational levels.

The mission of SLEOs is to enhance entrepreneurial abilities and raise the awareness, aspirations and knowledge about the entrepreneurial activities of students (Clark et al. 2008). Therefore, SLEOs respond to the European Union’s call for the need to stimulate entrepreneurial abilities of all future workers (JADE 2017).

In these organizations, students work in teams, stimulate their creativity by getting in touch with other students from different backgrounds and of different nationality and gain soft skills that can ultimately affect their business success (Rubin et al. 2002; Heckman and Kautz 2012). The activities of SLEOs are structured through learning by doing programs and advice from other associates. These organizations form the basis of experiential learning, and create a supportive environment within which one can take risks, network and attend several entrepreneurial events (Siivonen et al. 2019). SLEOs in fact allow their members to take part in multidisciplinary and international entrepreneurial events and activities.

Participation in a SLEO allows students to learn how to work in multidisciplinary and international teams, to improve their networking abilities, to interact with entrepreneurs, professors, industry experts and companies, to speak in public and to attend entrepreneurial events. Students can also participate in consultancy activities, organize events and develop their own projects. These are all situations that echo entrepreneurial contexts (Fayolle and Gailly 2009; Wright et al. 2017) and are aimed at forging students’ minds, values, attitudes and self-understanding. Therefore, SLEOs are an important instrument to foster students’ entrepreneurial abilities and to better prepare them for the uncertainties of modern, market-driven societies.

Although these organizations are present in almost all universities in Europe (Preedy and Jones 2015, 2017), SLEOs are still a somewhat under-studied phenomenon in the field of entrepreneurship and managerial education. A few researchers have recently started to investigate the activities performed by SLEOs and their role in stimulating entrepreneurial abilities and entrepreneurial intention (Pittaway et al. 2011, 2015; Gibcus et al. 2012; Padilla-Angulo 2017; Preedy and Jones 2017; Siivonen et al. 2019). Pittaway et al. (2011), on the basis of 10 unstructured interviews, a series of telephone interviews and e-mail postcards sent to different kinds of student clubs, showed that students’ engagement in entrepreneurship clubs and societies provides enhanced opportunities for learning by doing. In a follow-up work, Pittaway et al. (2015) investigated the nature of the learning process that students encounter when they are members of clubs. They pointed out several learning benefits, such as learning through mistakes, learning by doing and learning from entrepreneurs, that simulate important aspects of entrepreneurial intention. Pittaway et al. (2015) also found that students want to get in contact with entrepreneurs in order to approach the domain of entrepreneurship and therefore learn from their experiences. Additionally, complementing data based on 20 UK universities with face-to-face interviews, Preedy and Jones (2015) showed that SLEOs are widely diffused in many universities and act as important links among universities in the provision of entrepreneurial support. The authors found that SLEOs in fact foster students’ entrepreneurial abilities, thanks to such activities as networking. The correlation between entrepreneurial intention and participation in SLEOs of different types has been investigated in a few recent works. Padilla-Angulo (2017) examined the role of general student associations in developing students’ entrepreneurial intention at early educational stages. The results of a survey on 237 first-year undergraduate business school students revealed that student associations increase the entrepreneurial intention of first-year students. Padilla-Angulo (2017) also pointed out that student organizations include many activities that stimulate entrepreneurial abilities, such as searching for sponsors and raising money, networking, public speaking and working in a team. Gibcus et al. (2012), on the basis of a survey of 2,621 alumni of European higher education institutions (of which 288 were JEE alumni), pointed out that JEE members had higher scores on entrepreneurship skills and were more eager to become entrepreneurs than the other students. According to Gibcus et al. (2012), these results derive from the fact that JEE members have the opportunity of developing entrepreneurial abilities as a result of their taking part in practical projects, such as running professional studies for companies and managing the JEE organization themselves. Moreover, Preedy and Jones (2017) showed that SLEOs improve students’ networking and leadership abilities and stimulate entrepreneurial activities, but also prepare students for the job market. In the same way, Fayolle and Gailly (2015) found a link between the formation of entrepreneurial intention and participation in or contribution to setting up and managing a SLEO. However, these studies generally explored whether the simple fact of belonging to a SLEO contributes to developing entrepreneurial intention, rather than the extent to which the specific individual and organizational factors of students belonging to SLEOs affect their entrepreneurial intention. This paper aims at filling this gap in the extant literature.

An example of SLEO: JEE

JEE is a Brussels-based, non-profit, non-governmental organization that is affiliated with the European Commission and the European Parliament, which was established and is managed solely by students (EC 2006; Gibcus et al. 2012). Before 2019, JEE was known as JADE (JADE 2019). According to the motto “learning-by-doing”, their associates bridge the gap between academia and the real business world, thus stimulating students’ entrepreneurial abilities (JADE 2017). Today, the students involved in JEE, through running enterprises, have a turnover of 16 million euros per year.

The JEE student network is aimed at helping all students develop their entrepreneurial abilities (JADE 2017). Students from different fields of study, educational levels and nationalities work together to test and implement theoretical insights from university courses by learning and developing an entrepreneurial attitude through the concept of learning by doing. Therefore, JEE is also aimed at changing the personal environment and social norm of students, which in turn can enhance their entrepreneurial abilities and intention. JEE has recently attracted a great deal of attention from political leaders, who have expressed interest in its activities (JADE 2017). This is due to the fact that policy makers want to foster an entrepreneurial culture and to increase students’ entrepreneurial abilities (Lewis and Llewellyn 2004; O’Connor 2013; Wright et al. 2017; Siivonen et al. 2019; Varano et al. 2019; Barbini et al. 2020). Entrepreneurial abilities have in fact been recognized as being useful for personal, professional and/or business activities, but also for the opportunities and challenges that an employer or an organization has to face (EC 2006). Consequently, the presence of JEE has increased in several universities, not only in the European Union, but also outside.

The antecedent of JEE appeared in France in 1967, when the first SLEO was founded at the ESSEC Business School in Paris (Pittaway et al. 2015). Some other SLEOs were then created around Europe and elsewhere. In 1992, some of these organizations formed National Confederations and took the decision to create a larger-scale organization, thus giving rise to JEE. In 1988, JEE went beyond the bounds of Europe and created a sister confederation in Brazil. Brazil Jùnior today has almost 20,000 participants. Additionally, in 2013, JET—Junior Enterprises of Tunisia—was founded, and this was followed by the Canadian Confederation of Junior Enterprises (JC3) in 2015. Under an international cooperation agreement, the confederations continue to move the organization forward to reach new countries and continents. Today, with the first organization in the USA, and Morocco, and new Junior Initiatives in Turkey, and Australia, they are present in 14 countries in Europe and in over 40 countries around the world, with a network of 30,000 students in Europe and over 51,000 students around the globe. In addition, the confederations work closely with universities to foster an entrepreneurial culture and ecosystem. Therefore, JEE can be defined as global and it is continuously attempting to enlarge its boundaries.

JEE carries out many activities, ranging from lobbying, support to consulting/entrepreneurial projects and the organization of events (to stimulate the dialogue between students, policy makers, experienced professionals and entrepreneurs, and to create a bridge with the job market). Table 1 illustrates JEE’s main activities.

In terms of its organizational structure, JEE appears as a bottom-up organization: the participants (called Junior Entrepreneurs) are at the base of the organizational pyramid, and they, in turn, choose the leaders of their local SLEOs (called Junior Enterprises). These leaders represent and guide the local organizations, and manage the relationship with clients, suppliers and partners and in general with all the external stakeholders. Local SLEOs select their country representatives at the national level, and these representatives work in the national confederation to promote the goals and answer the needs of each SLEO at a country level. Each country elects its International Manager, the person responsible for maintaining contact and ensuring effective communication between the national and the European level, namely JEE. Moreover, all national representatives, gathered together in the General Assembly, elect the JEE Executive Board, which, living and working in Brussels, represents the organization at the European level and maintains relationships with the partners, institutions and the other confederations throughout the world. JEE plays an important role in these organizations at a European level by connecting them with European Institutions and the opportunities offered by these institutions. These SLEOs are legally registered as NGOs, and therefore have their own Statutes and all other legal requirements based on their country of operation.

Research design

Sample and data collection

The empirical data used to investigate the drivers of students’ entrepreneurial intention were obtained from an online survey conducted in 2016 among the members of the European and Tunisian JEE networks. The authors developed the survey, which is presented in the Appendix, together with the JEE board of directors. In addition, OECD provided advice on how to structure the survey and suggested some key questions that needed to be addressed.

The survey was sent first to the International Manager of each JEE confederation, who then passed it on to the Presidents of the Junior Enterprises (henceforth JEs) belonging to the confederations. All the members of the JEs were invited to fill in the survey. The survey was written in both French (to address the French and Tunisian confederations) and English (to address the remaining JEE members).

Out of 420 associates who had received the survey, a total of 261 members answered the survey, thus yielding an effective response rate of 62%. A check on non-response bias was made with respect to all the survey items (Armstron and Overton 1977) and it was found to be minimal. Therefore, the sample is representative of the population.

Descriptive statistics

The survey presented 33 questions covering the general data of the students, the international mindset, the educational and work background, their involvement in JEs and future career scenarios. On average, the respondents were 22 years old and were thus still undergraduate students. Out of the 261 respondents, 54% were women. This is an interesting data, given that previous studies showed that men are generally more inclined toward entrepreneurship (Shinnar et al. 2012), although gender does not always play a determinant role in start-up activities (Verheul and Thurik 2001).

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the distribution of the respondents according to their nationality and field of study.

A non-trivial fragmentation regarding the respondents’ nationality appears: the higher percentages of respondents are Tunisian (29%), Italian (26%) and Portuguese (23%), followed by French (7%), Spanish (5%), German (3%), Belgian (2%), Austrian (1%) and British (1%). Other nationalities (Croatian, Dutch, Polish, Swedish and Swiss) overall account for 2%. As far as the field of study is concerned, most students are enrolled in Science and Technology (47%) and Business (42%), while only a few students study Human Science (9%). Only a few respondents are enrolled in Languages and Communication (5%), Art and Sport (2%) and Biological Science (3%). In addition, the JEE members are also from different educational levels. In fact, the respondents are either in their first (13%), second (24%), third (23%), fourth (24%), fifth (13%) or later (2%) years of university. The following universities show a higher frequency (more than 5%): Universidade Católica Portuguesa (8%), Université de Monastir École Nationale d’Ingénieurs de Monastir (7%), École de Traduction, d’Interpretation de Conference (7%), Politecnico di Milano (7%), Universidade do Minho (7%), Université de Tunis el Manar Ecole Nationale d’Ingénieurs de Tunis (7%), Università degli Studi di Milano (6%) and Université de la Manouba Ecole Nationale des Sciences de l’informatique (5%). The JEE members come from 48 different universities. This indicates that JEE involves students from different countries, different fields of study and different educational levels.

Since JEE is international, their associates actively develop an international mindset. In fact, out of the 261 respondents, 65% speak more than two foreign languages. Almost all students speak English (97%). Most of them speak French (53%), and fewer speak Spanish (28%), Italian (27%), Arabic (24%), Portuguese (24%), German (20%), Chinese (4%), Catalan (2%), Dutch (2%), Russian (2%) and Polish (1%). It should be noted that, when added together, the total is not 100%, because the respondents had the possibility of choosing several answers. In addition, 39% of the students reported that they had lived abroad and 25% declared they had participated in exchange programs (most of which were in Europe, 63%).

As far as their work experience is concerned, almost half of the associates reported they had worked as volunteers in another organization and that they had work experience (48% and 45%, respectively).

In addition, it is interesting to note what are the skills that JEE helps its members develop. Figure 3 illustrates that participation in JEE activities helped associates develop teamwork (18%) and communication skills (16%), and learn to take responsibility (14%). In fact, when students were asked the reasons that drove them to take part in the organization, most of them reported that the main reason was to improve their skills (87%) and their networking (65%). Additionally, 83 associates (32%) answered they were driven to have a positive impact on society and a total of 60 associates (23%) answered that they entered the organization in order to learn how to start a business. Only 40 students (15%) indicated that they joined JEE for leisure purposes.

Variables

The dependent variable (entrepreneurial intention) was derived from the answers to a specific question in the survey (Krueger 1993): “How do you see yourself when you finish your current studies?”. The respondents could answer by choosing among five different options: (i) becoming an employee in the public sector; (ii) becoming an employee in the private field; (iii) starting their own company; (iv) starting a new study program; or (v) other. The dependent variable is therefore a binary variable that is equal to 1, if the respondents answered they wanted to start their own company, and 0 otherwise, as has been done in similar works (e.g. Laspita et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2014; Criaco et al. 2017).

The explanatory variables refer to both specific organizational and individual factors that affect students’ entrepreneurial intention. In other words, this study has used three different organizational-specific factors. First, it considers the number of hours per week that, on average, an associate spends working for JEE. This variable reflects the effort that students put into working for the organization. Since SLEOs can stimulate entrepreneurial abilities through their activities (Pittaway et al. 2011, 2015), it was expected that this variable could influence students’ entrepreneurial intention. In fact, the more hours students work for the organization, the more activities they are able to attend, organize and accomplish and hence, the higher the likelihood is that they will increase their entrepreneurial intention. During the hours spent in the association, members can have the opportunity to learn by doing, to add practical experience to their theoretical skills and to develop entrepreneurship abilities (Padilla-Angulo 2017). In other words, SLEOs help students improve their entrepreneurial abilities and intention through different mechanisms: by shaping the social norms, such as students’ personal relationships, that influence the process of entrepreneurial learning (Cope 2005; Pittaway and Cope 2007) and by emulating entrepreneurship activities (Fayolle and Gailly 2015), thus stimulating students’ problem-solving abilities, as well as their communication, leadership and team work skills (Preedy and Jones 2017).

Second, another organizational-specific regressor is the number of projects that students have carried out within JEE. The involvement in a greater number of projects can lead students to enhance their experience, improve their technical and soft skills (e.g. project management, communication, leadership and team work) and develop a network of contacts from industry and service professionals, thereby influencing their entrepreneurial intention. Networking is in fact a key component for entrepreneurship (e.g. Zimmer and Aldrich 1987; Sandhu et al. 2011; Wright et al. 2017), since it reduces the perceived risk of action (Brüderl and Preisendörfer 1998) and increases determination and perseverance in a process (Gimeno et al. 1997). In addition, students can foster their entrepreneurial abilities by running real projects (Pittaway et al. 2011; Gibcus et al. 2012; Preedy and Jones 2017). In fact, consulting projects can also have an impact on students’ entrepreneurial intention (Kassean et al. 2015). In other words, by taking part in real experiences, students can play the role of a real entrepreneur (Corbett 2005; Clark et al. 2008) since they need to manage people and money, work in a team and negotiate (EC 2016).

Third, the last predictor variable at the organization level is the number of events that students have attended. This variable concerns the events organized by JEE itself, local JEs and the National Confederations, aimed at improving students’ skills, extending their networks and enhancing their entrepreneurial intention. During these events, students can meet other peers with similar interests and can work on new ideas.

In addition to organizational-specific factors, the correlation between individual-specific factors and students’ willingness to start an entrepreneurial business has been tested. The independent variables include the respondent’s field of study, their international mindset (knowledge of foreign languages and participation in exchange programs) and their work experience. As outlined in prior works, a student’s field of study can have an impact on entrepreneurial intention (Schwarz et al. 2009; Edelman et al. 2016; Criaco et al. 2017; Laskovaia et al. 2017; Morris et al. 2017). It has been found that students enrolled in Business studies have greater entrepreneurial intention than their colleagues (Schwarz et al. 2009; Wang and Verzat 2011; Edelman et al. 2016; Morris et al. 2017). Nevertheless, Criaco et al. (2017) also found a positive correlation between Engineering students and entrepreneurial attitudes. Similarly, Souitaris et al. (2007) pointed out that entrepreneurship programs raise the entrepreneurial intention of Science and Engineering students. Therefore, this study has also analysed whether different fields of studies can affect students’ entrepreneurial intention. In other words, the analyses included Science and Technology as a dummy variable that was equal to 1 if the student’s field of study was Science and Technology, and 0 otherwise.

In addition, the international mindset of the students was proxied by means of two variables: the number of foreign languages spoken and whether they had completed an exchange program. Mastering more than two foreign languages is important for business purposes (e.g. to facilitate interactions with people from different cultures). In fact, language ability is an important source for entrepreneurship since it allows entrepreneurs to successfully create market entry and new foreign market choice strategies more easily (Johnstone et al. 2018). Moreover, several studies (see Adesope et al. 2010 for a review) have also shown that individuals who speak two languages are endowed with better problem-solving skills and creativity. In addition, Ellis (2011) indicated linguistic distance as a major barrier to the communication of information about new opportunities. Therefore, it was expected that speaking more than two foreign languages would be positively correlated with developing entrepreneurial intention. The variable of interest was a dummy variable that was equal to 1 if the student spoke more than two foreign languages, and 0 otherwise. In other words, the variable was equal to 1 only if a student knew the language of his/her country of origin, plus two more languages. For instance, if a French student knew French, English and Spanish, the language variable was equal to 1.

In addition, having completed an exchange program can also have an impact on students’ entrepreneurial intention (Brandenburg et al. 2014). As Brandenburg et al. (2014) pointed out, almost one out of ten Erasmus students start their own company, and more than three out of four plan to do so. This is because exchange programs allow students to create an international network, improve their soft skills and get in touch with different cultures, thus obtaining a better understanding of the international market (Cavallo et al. 2019; Varano et al. 2019). In fact, these programs can have an impact on the social norm of an individual. For instance, in the French context, Fayolle and Gailly (2015) found a significant correlation between French engineering students’ entrepreneurial intention and living abroad for at least six months. This study has therefore included the exchange program variable as a dummy variable equal to 1 for students who have been on an exchange program, and 0 for those who have not.

An additional personal-specific variable is students’ work experience (e.g. Carr and Sequeira 2007; Laskovaia et al. 2017). Prior family business exposure has been found to correlate with the formation of entrepreneurial intent (Carr and Sequeira 2007). In addition, experience in industry has been shown to have a positive impact on entrepreneurial performance (Cassar 2014; Smolka et al. 2018). Similarly, Edelman et al. (2016) showed that students’ previous work experience is positively associated with a greater scope of venture activities. Laskovaia et al. (2017) pointed out that the experience of students in industry positively impacts their new venture performance. However, Sandhu et al. (2011) found no significant relationship between work experience and entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, this study has included a dummy variable equal to 1, if a student had a prior work experience, and 0 otherwise.

Moreover, this study has included several control variables in the model specification. The first of these controls is gender. Even though Verheul and Thurik (2001) showed that gender does not play an important role for start-up activities, it is generally accepted than men have more entrepreneurial intention than women (Mathews and Moser 1995; Harada 2003; Wilson et al. 2007; Schwarz et al. 2009; Yordanova and Tarrazon 2010; Shinnar et al. 2012; Criaco et al. 2017; Morris et al. 2017). Research indicates that women have both lower entrepreneurial self-efficacy and lower entrepreneurial intention (Chen et al. 1998; Kourilsky and Walstad 1998; Criaco et al. 2017). Mazzarol et al. (1999) found that women are less likely to be founders than men. However, as suggested by Bandura et al. (2001), women may be influenced more by any perceived skill deficiency in the entrepreneurial field than men. In their study, Kourilsky and Walstad (1998) compared perceptions of knowledge with actual knowledge of entrepreneurial skills and showed that while the skill levels of men and women were comparable, the latter were more likely to feel unprepared. Minniti et al. (2004) reported that these patterns emerge globally among adult women (i.e. women show lower levels of confidence and preparedness in their ability to succeed as entrepreneurs). Nevertheless, Smolka et al. (2018) found that being female is not significantly related to start-up performance. Empirical evidence also indicates that, despite the growth in female entrepreneurship, men entrepreneurs are still almost twice as many as women entrepreneurs (Bosma and Levie 2009). In addition, as in previous studies, students’ age has also been included as an additional control (Barber 2015; Minola et al. 2016; Criaco et al. 2017; Laskovaia et al. 2017; Morris et al. 2017; Smolka et al. 2018). Students’ age can be correlated with entrepreneurial risk taking (Barber 2015). Previous works have shown that age is correlated with entrepreneurial intention (Hatten and Ruhland 1995; Harada 2003; Schwarz et al. 2009; Criaco et al. 2017; Smolka et al. 2018). Most studies have highlighted that younger people have a higher intention of starting new firms (Schwarz et al. 2009; Edelman et al. 2016; Criaco et al. 2017; Smolka et al. 2018), while only a few have pointed out the opposite (Cressy 1996). The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the student’s country of study has been included as a control (Laskovaia et al. 2017). Information on GDP has been derived from the World Bank dataset for the year 2015. It has been pointed out that countries with a lower GDP are generally associated with higher entrepreneurship rates (Wennekers et al. 2005; Uhlaner and Thurik 2007; Stephan and Uhlaner 2010). This is due to the lack of steady jobs, a fact that stimulates people to become entrepreneurs (Audretsch and Thurik 2001; GEM 2002; Dutta and Sobel 2018). The most recent Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report (GEM 2017) has in fact shown Guatemala as the country where becoming an entrepreneur is the best career choice, Burkina Faso as the country with the highest status for successful entrepreneurs, and Jamaica as the country with the highest attention toward entrepreneurship. Moreover, Laskovaia et al. (2017) found that GDP has a negative effect on new venture performance. Furthermore, Sambharya and Musteen (2014) found a curvilinear relationship between per capita GDP and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.

Table 2 illustrates the definitions of the variables used in the empirical analysis, as well as the main descriptive statistics. The Appendix reports the correlation matrix of the variables (Table 6). The Table 6 shows that the value for the correlation between two regressors is never higher than 0.40. The exception is the expected correlation between N_events and Time_spent (0.42). Therefore, these two variables are not in the same regression analysis.

Empirical results

In order to investigate which factors shape the willingness of students belonging to SLEOs to become entrepreneurs, a logistic regression analysis has been performed. Since two predictor variables are highly correlated (N_events and Time_spent), this study has reported the results separately in two different tables.

Table 3 reports the logit estimates, in which the variable Time_spent is included among the regressors. Model 1 is the baseline model. Model 2 adds the student’s education field. Model 3 includes the variables that reflect the student’s foreign experience. The student’s work experience is introduced in model 4.

In all the model specifications, the Time_spent variable presents a statistically significant and positive impact on students’ entrepreneurial intention. This result indicates that the time that students spend in JEE positively shapes their subsequent willingness to start a new business. In fact, the higher the time devoted to the activities organized by JEE is, the higher the likelihood that students will increase their entrepreneurial abilities that will ultimately affect the development of their entrepreneurial intention. Surprisingly, the analyses have not revealed a statistically significant impact of the number of projects that students have carried out in this organization on their entrepreneurial intention. An explanation of this result could be related to the consultancy-based nature of some of these projects. Although no information on the contents of the projects is available, informal talks with some JEE members have revealed that, in many cases, projects have opened the door to contacts (and subsequent hiring) with consultancy companies. Several JEs enter into partnership or informal agreements that give their members some advantage in being hired by local companies. For instance, if a company is recruiting, it might directly ask JEs to let some members apply for an evaluation.

The mere number of projects alone may not be sufficient to explain the members’ entrepreneurial intention, as the content of the project probably would have. The estimates of the marginal effects show that when the Time_spent variable moves from zero to its mean value, the probability of having entrepreneurial intention increases by 0.5 percentage points.

As far as individual-level factors are concerned, the Science and Technology field of study has a statistically significant and positive impact on students’ entrepreneurial intention, as found by Criaco et al. (2017). This effect is significant at a 5% level in all the model specifications. Owing to the fact that the two variables concerning the field of study (Science and Technology and Business) together present a high correlation (− 0.6520), Business was not included in the analyses. However, this study has also run the same regressions controlling for Business instead of Science and Technology, without finding any significant effect of the Business field of study. In terms of marginal effects, being enrolled in the Science and Technology field of study significantly increases the probability of developing entrepreneurial intention by 13.17%.

The estimates show that students who speak more than two foreign languages are more likely to develop entrepreneurial intention than their peers. Here again, the magnitude of the effect is high. The probability of having entrepreneurial intention is, on average, about 10 percentage points higher for students who speak more than two foreign languages.

Additionally, the GDP of the country of study was found to be negatively and significantly associated with students’ entrepreneurial intention. This result is interesting, because it indicates that students from lower income countries are more willing to create new businesses than their peers, despite their country’s poor growth perspectives. Laskovaia et al. (2017) found the same result. Moreover, based on the human capital theory, Dutta and Sobel (2018) have explained that less developed countries have a high rate of entrepreneurs, also known as ‘necessity’ entrepreneurs.

Table 4 reports the logit estimates where the N_events variable is included among the regressors. Model 1 is the baseline model. Model 2 adds the student’s education field. Model 3 includes the variables that reflect the student’s experience abroad. Student’s work experience is introduced in model 4.

The N_events variable displays a statistically significant and positive sign in all the model specifications (at a 5% significant level). A unit change in the N_events variable increases the probability of having entrepreneurial intention by 0.004. This result reinforces the expectation that the higher the effort that students put into JEE activities is, the higher the likelihood of developing entrepreneurial intention is. All the results presented in Table 3 have been confirmed when the N_events variable was substituted with the Time_spent variable in the regression analyses.

In conclusion, the results show how students’ participation in JEE positively affects their entrepreneurial intention. In fact, the findings show that the more effort students put into this organization and the more events they follow, the higher the probability of increasing their entrepreneurial intention is. The Science and Technology field of study and the knowledge of more than two foreign languages are both important drivers of entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, the results confirm the recent work of Johnstone et al. (2018) concerning the role played by language ability in entrepreneurship. In addition, the results show that entrepreneurship is also interesting for technical students (Souitaris et al. 2007).

Conclusion

Developing and promoting entrepreneurship is one of the key policy objectives of many countries around the world (e.g. Lewis and Llewellyn 2004; O’Connor 2013). Therefore, several researchers (e.g. Fonseca et al. 2001; Hoppe 2016; Wright et al. 2017; Siivonen et al. 2019; Barbini et al. 2020) have started to study which activities are able to stimulate entrepreneurship. Numerous studies have examined the role played by specific entrepreneurship education programs in influencing students’ entrepreneurial intention (Raffo et al. 2000; Peterman and Kennedy 2003; Souitaris et al. 2007; Pruett et al. 2009; Engle et al. 2010; Oosterbeek et al. 2010; Lanero et al. 2011; Sánchez 2013), but this paper has focused on how the participation of students in SLEOs affects their entrepreneurial intention.

It has been pointed out that SLEO members have the opportunity of networking, sharing ideas, working in multidisciplinary and international teams and attending entrepreneurial events and workshops. As suggested by Fayolle and Gailly (2009), SLEOs allow students to work in a similar environment as the one faced by entrepreneurs. Therefore, SLEOs are considered as important actors in promoting an entrepreneurial environment and culture that can foster entrepreneurship at university (Siegel and Wright 2015). However, despite being an important and growing phenomenon, only a few studies have so far analysed SLEOs (Pittaway et al. 2011, 2015; Padilla-Angulo 2017; Preedy and Jones 2017; Siivonen et al. 2019).

In order to study the impact of SLEOs on students’ entrepreneurial intention, this research developed a survey in 2016 in collaboration with one of the most famous SLEOs in the world: JEE. The answers to a survey distributed to JEE members have revealed that the more time spent in JEE and the higher the number of events students attended are, the higher their entrepreneurial intention was. We argue that the activities in JEE allow students to improve their social capital (e.g. network connections) and human capital (e.g. entrepreneurial abilities), which are fundamental for entrepreneurs (Hsiao et al. 2016; Wright et al. 2017). Our results indicate that JEE plays an important role in driving students’ entrepreneurial intention and in fostering the entrepreneurial culture and ecosystem inside a university. In fact, SLEOs are fostering students’ entrepreneurial spirit and competences by proactively engaging their members in decision-making, encouraging them to start their own projects, and actively look for new opportunities. For instance, by being members of JEE, students can develop their entrepreneurial intention through learning through mistakes, learning by doing and learning from entrepreneurs (Pittaway et al. 2015). Moreover, they can create multidisciplinary and international teams, share their experiences with other peers interested in becoming entrepreneurs, enlarge their network and meet entrepreneurs (Padilla-Angulo 2017). These activities allow students to improve their hard and soft skills, such as entrepreneurial skills, team working, creativity, public speaking, networking, intercultural understanding and project management. Furthermore, thanks to the sharing of ideas, students can receive feedbacks on their entrepreneurial ideas (Pittaway et al. 2011, 2015). Therefore, SLEOs are bottom-up organizations able to improve students’ entrepreneurial intentions as a result of their activities.

Our findings indicate that SLEOs need to be considered in future research on entrepreneurial intention and abilities. For instance, it could be interesting to understand whether students’ experiences in SLEOs have a greater impact on students’ entrepreneurial intention and abilities than entrepreneurship courses. In this way, it will be possible to analyse the combined effect of SLEOs and entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention and abilities. In addition, since SLEOs are important actors in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, they should be included in future studies on the entrepreneurial culture and ecosystem of universities. It could be interesting to understand the effect of the collaboration of SLEOs with other local actors, inside and outside the university, in order to offer entrepreneurship education (e.g. events, workshops, business competitions, hackathons) with the ultimate aim of fostering the entrepreneurial culture of students at universities.

The results also show that when students speak more than two foreign languages, and their study field is Science and Technology, there is a higher probability of their developing entrepreneurial intention. In fact, speaking more than two foreign languages gives students an opportunity to connect with people (e.g. students, as well as experts and potential customers) from different cultures and thus to better form an entrepreneurial mindset. This means that students can enlarge their network and may even change their social norms and environment. Language ability is an important topic that has already been examined in entrepreneurship research (Johnstone et al. 2018), because speaking more languages seems to stimulate creativity and problem-solving (e.g. Adesope et al. 2010). However, future research needs to analyse the role of language skills on entrepreneurial abilities and intention in more detail. In addition, a more scientific background allows students to have a greater knowledge of technology than students from other backgrounds and this knowledge can be turned into real entrepreneurial projects, thus affecting the probability of starting a new business. Therefore, it is also important to stimulate entrepreneurial intention in technical students (Souitaris et al. 2007). In conclusion, the results indicate that, in addition to experiences in SLEOs, individual-specific attributes and the curriculum are also important factors that lead to shaping the willingness of students to become entrepreneurs. However, this study has not found any difference according to the gender of students. This may be due to the fact that females who choose to be part of SLEOs have a greater self-efficacy than the average student. This aspect deserves to be investigated in future research.

Our findings offer several theoretical and practical implications for SLEOs, universities and policy makers. SLEOs are encouraged to enhance their visibility and lobbying, both at a local and an international level, in order to be better recognized as drivers of student entrepreneurship. Given the usefulness of these organizations in developing students’ entrepreneurial intention, it is advisable for universities to support and help students interact with them. Furthermore, universities could strengthen their technology transfer and entrepreneurial activities by including SLEOs in consultations, and foster SLEO interactions with other actors who promote entrepreneurship and technology transfer activities. They could, for instance, favour interactions with universities, entrepreneurship professors, incubators, entrepreneurship research centres and technology transfer offices. Universities that excel in offering these opportunities could thus differentiate themselves from other universities and attract a higher number of students. Moreover, policy makers could sustain SLEOs financially and foster their interactions with other entrepreneurial system actors (e.g. incubators, business angels, venture capitalists, entrepreneurship associations). As explained by Alvarado et al. (2017), access to financing is fundamental to regional entrepreneurship. Therefore, all the actors in the entrepreneurial ecosystem are called upon to financially support SLEOs. For instance, SLEOs might take advantage of the Erasmus, Erasmus + and Extra-UE programs supported by the European Commission. SLEOs could in fact play an important role within the entrepreneurial ecosystem. For instance, they could support the development of an entrepreneurial culture, by organizing events and public initiatives and by allowing students from different backgrounds, different education levels and different countries to work in groups to enhance their entrepreneurial skills. Furthermore, SLEOs could connect like-minded individuals within the community and create a link between different local actors. Many universities have in fact started to recognize this role (for example UC Berkeley and Aalto University) and to consider SLEOs as part of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in which the university is involved. Moreover, as Pittaway et al. (2015) suggested, students tend to join these SLEOs in order to improve their networking, learning through mistakes and learning by doing skills, and to acquire soft skills and experiences. Finally, as recently suggested by Rippa and Secundo (2019), it is important to foster student and academic entrepreneurship activities by applying digital technologies. SLEOs can also apply digital technologies in order to help universities and students to foster student and academic entrepreneurship.

Our results have implications for policy. SLEOs are key agents in the development of an entrepreneurial culture among young people and the study of the role they play in shaping the entrepreneurial intention of their members is crucial in evaluating if there is a case for public policy intervention to stimulate their activity. Our research recommends policy makers to support SLEOs’ activities both inside and outside the university environment. Policy makers might need to design diversified policy initiatives and support measures to fit distinct entrepreneurial environments and to respond to different endorsements by universities.

Our study is not without limitations. The main limitation is that the survey has only been addressed to the members of one SLEO (albeit one of the largest) and a control sample is lacking. Furthermore, the sample has a population of diversified nationalities, with certain countries being present with a higher percentage than others in the sample. Additionally, the analysis was only conducted in Europe. Another limitation is that it is not possible to know whether the students that responded to the survey will continue on their path toward entrepreneurship. One way of enhancing the analysis would be to keep trace of the students’ career progress. In this way, it would be possible to verify whether the students have actually become entrepreneurs and whether, and how, the SLEO experience served as a stepping stone to venture creation. Future research could therefore study which types of start-ups have been founded by SLEO associates and how the founders evaluate their experience in the SLEO. Moreover, it could be interesting to focus on students enrolled not only in Europe but also outside Europe (such as in the USA, China or in developing countries) in order to understand whether and how the impact of SLEOs changes across countries and to measure how the cultural differences of different countries impact entrepreneurial intention (Farashah 2015; Paul et al. 2017). As suggested by Salinas et al. (2018, 2019), both institutional (e.g. tax, labour or environmental regulations) and informal rules (i.e. linked to norms, values and beliefs prevailing in each society) affect the level of entrepreneurship activities. Future studies might pay attention to the importance that formal and informal rules play in SLEOs and in forging students’ entrepreneurial intentions.

In addition, taking part in a SLEO is probably not the only factor of influence on entrepreneurial intention. It could interact with other factors, such as the use of social media (and who students follow on social media), the role played by their professors and mentors and the societal appraisal of entrepreneurship, to mention just a few. Moreover, it would be intriguing to assess the impact of SLEOs on the entrepreneurial ecosystem and society as a whole.

References

Abreu M, Grinevich V (2013) The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities. Res Policy 42(2):408–422

Adesope OO, Lavin T, Thompson T, Ungerleider C (2010) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the cognitive correlates of bilingualism. Rev Educ Res 80(2):207–245

Alvarado R, Peñarreta M, Armas R, Alvarado R (2017) Access to financing and regional entrepreneurship in Ecuador: an approach using spatial methods. Int J Entrepreneurship 21(3):1–9. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/Access-to-financing-and-regional-entrepreneurship-in-ecuador-an-approach-using-spatial-methods-1939-4675-21-3-111.pdf

Anderson AR, Warren L (2011) The entrepreneur as hero and jester: enacting the entrepreneurial discourse. Int Small Bus J 29(6):589–609

Arenius P (2005) The psychic distance postulate revised: from market selection to speed of market penetration. J Int Entrepr 3(2):115–131

Armstron JS, Overton TS (1977) Estimating non-response bias in mail survey. J Mark Res 14(3):396–402

Arranz N, Ubierna F, Arroyabe MF, Perez C, Fdez. de Arroyabe JC, (2017) The effect of curricular and extracurricular activities on university students’ entrepreneurial intention and competences. Stud High Educ 42(11):1979–2008

Audretsch DB, Thurik AR (2001) What’s new about the new economy? Sources of growth in the managed and entrepreneurial economies. Ind Corp Change 10(1):267–315

Bacigalupo M, Kampylis P, Punie Y, Van den Brande G (2016) EntreComp: the entrepreneurship competence framework. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union; EUR 27939 EN. https://doi.org/10.2791/593884

Bae TJ, Qian S, Miao C, Fiet JO (2014) The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: a meta-analytic review. Entrep Theory Pract 38(2):217–254

Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara G, Pastorelli C (2001) Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Dev 72(1):187–206

Barber D (2015) An experimental analysis of risk and entrepreneurial attitudes of university students in the USA and Brazil. J Int Entrepr 13(4):370–389

Barbini FM, Corsino M, Giuri P (2020) How do universities shape founding teams? Social proximity and informal mechanisms of knowledge transfer in student entrepreneurship. J Technol Transfer:1–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-020-09799-1

Birley S (1985) The role of networks in the entrepreneurial process. J Bus Ventur 1(1):107–117

Blenker P, Frederiksen SH, Korsgaard S, Müller S, Neergaard H, Thrane C (2012) Entrepreneurship as everyday practice: towards a personalized pedagogy of enterprise education. Ind High Educ 26(6):417–430

Bonaccorsi A, Colombo MG, Guerini M, Rossi-Lamastra C (2014) The impact of local and external university knowledge on the creation of knowledge-intensive firms: evidence from the Italian case. Small Bus Econ 43(2):261–287

Bosma N, Levie J (2009) Global entrepreneurship monitor: 2009 executive report. Available at http://www.gemconsortium.org

Brandenburg U, Berghoff S, Taboadela O (2014) The Erasmus impact study: effects of mobility on the skills and employability of students and the internationalisation of higher education institutions. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.https://doi.org/10.2766/75468

Braunerhjelm P, Acs ZJ, Audretsch DB, Carlsson B (2010) The missing link: knowledge diffusion and entrepreneurship in endogenous growth. Small Bus Econ 34(2):105–125

Brüderl J, Preisendörfer P (1998) Network support and the success of newly founded business. Small Bus Econ 10(3):213–225

Carr JC, Sequeira JM (2007) Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: a theory of planned behavior approach. J Bus Res 60(10):1090–1098

Cassar G (2014) Industry and startup experience on entrepreneur forecast performance in new firms. J Bus Ventur 29(1):137–151

Cavallo A, Ghezzi A, Colombelli A, Casali GL (2020) Agglomeration dynamics of innovative start-ups in Italy beyond the industrial district era. Int Entrep Manag J 16(1):239–262

Cavallo A, Ghezzi A, Ruales Guzmán BV (2019) Driving internationalization through business model innovation: evidences from an AgTech company. Multinatl Bus Rev 28(2):201–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBR-11-2018-0087

Chen C, Greene P, Crick A (1998) Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J Bus Ventur 13(4):295–316

Clark G, Dawes F, Heywood A, Mclaughlin T (2008) Students as transferors of knowledge: the problem of measuring success. Int Small Bus J 26(6):735–758

Cope J (2005) Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 29(4):373–397

Cope J, Watts G (2000) Learning by doing: an exploration of experience, critical incidents and reflection in entrepreneurial learning. Int J Entrep Behav Res 6(3):104–124

Corbett AC (2005) Experiential learning within the process of opportunity identification and exploitation. Entrep Theory Pract 29(4):473–491

Cressy R (1996) Are business startups debt-rationed? Econ J 106(438):1253–1270. https://doi.org/10.2307/2235519

Criaco G, Sieger P, Wennberg K, Chirico F, Minola T (2017) Parents’ performance in entrepreneurship as a “double-edged sword” for the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 49(4):841–864

do Paço AMF, Ferreira JM, Raposo M, Rodrigues RG, Dinis A (2011) Behaviours and entrepreneurial intention: empirical findings about secondary students. J Int Entrepr 9(1):20–38

Dutta N, Sobel RS (2018) Entrepreneurship and human capital: the role of financial development. Int Rev Econ Finance 57:319–332

EC (European Commission) (2006) Entrepreneurship education in Europe: fostering entrepreneurial mind-sets through education and learning: the Oslo Agenda. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/entrepreneurship-education-europe-fostering-entrepreneurial-mindsets-through-education-and_ga

EC (European Commission) (2012) Effects and impact of entrepreneurship programmes in higher education. Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry, Brussels

EC (European Commission) 2016 Entrepreneurship education at school in Europe: Eurydice Report. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2797/301610

Edelman LF, Manolova T, Shirokova G, Tsukanova T (2016) The impact of family support on young entrepreneurs’ start-up activities. J Bus Ventur 31(4):428–448

Elia G, Secundo G, Passiante G (2017) Pathways towards the entrepreneurial university for creating entrepreneurial engineers: an Italian case. Int J Entrep Innov Manag 21(1–2):27–48

Ellis PD (2011) Social ties and international entrepreneurship: opportunities and constraints affecting firm internationalization. J Int Bus Stud 42(1):99–127

Engle R, Dimitriadi N, Gavidia J, Schlaegel C, Delanoe S, Alvarado I, He X, Baume S, Wolff B (2010) Entrepreneurial intent: a twelve-country evaluation of Ajzen’s model of planned behaviour. Int J Entrep Behav Res 16(1):35–57

Etzkowitz H, Webster A, Gebhardt C, Terra BRC (2000) The future of the university and the university of the future: evolution of ivory tower to entrepreneurial paradigm. Res Policy 29(2):313–330

EU (European Union) (2006) Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning. Off J Eur Union 49(L394):10–18

Farashah AD (2015) The effects of demographic, cognitive and institutional factors on development of entrepreneurial intention: toward a socio-cognitive model of entrepreneurial career. J Int Entrepr 13(4):452–476

Farny S, Frederiksen SH, Hannibal M, Jones S (2016) A CULTure of entrepreneurship education. Entrep Region Dev 28(7–8):514–535