Abstract

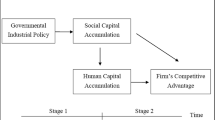

This paper proposes a dynamic model using a general equilibrium approach and shows that the coordination of public policies with suitable human resources training is a key factor for an economy to industrialize. We analyze three public policy domains: innovation policies; policies regarding human resources training, including wages and employment; and push policies. The omission or implementation of public policies, as well as their coordination, defines whether an economy stagnates in a poverty trap, or on the contrary, whether the economy is activated through industrialization processes. Such outcomes depend on what the initial state of the economy is like: whether it is on the left or the right of the industrialization frontier. The viability of crossing the industrialization frontier will depend on how these types of policies are coordinated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This idea was first developed by Rosenstein-Rodan (1943).

Alternatively, we may define segments within the continuum of goods, so that there are intermediate levels of aggregation. Then, we would have industrialization levels that differ between segments and λμ would be the average level of industrialization in the economy.

In several countries, the cost of formal education and vocational training is subsidized by the public sector, and the entire society absorbs this cost in a continuous form.

Also, this simplification can be approached by assuming that we had numerous generations, and if the new generation did not face the training cost, the proportion of high-skilled labor would be reduced. Since we are focusing on the proportions of different types of labor units, this simplification seems closer to its dynamics than assuming that high-skilled labor units remain so.

References

Accinelli E, Sanchez Carrera EJ (2012) The evolutionary game of poverty traps. The Manchester School 80(4):381–400

Acemoglu D (2002a) Directed technical change. The Review of Economic Studies 69(4):781–809

Acemoglu D (2002b) Technical change, inequality, and the labor market. Journal of Economic Literature 40(1):7–72

Alesina A (2003) The size of countries: does it matter? Journal of the European Economic Association 1(2-3):301–316

Allen RC (2011) Global economic history: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press

Amsden AH (1989) Asia’s next giant: South Korea and late industrialization. Oxford University Press on Demand

Arthur WB (1989) Competing technologies, increasing returns, and lock-in by historical events. The Economic Journal 99(394):116–131

Basu K (2003) Analytical development economics: the less developed economy revisited. MIT Press

Bils M, Klenow PJ (2000) Does schooling cause growth? American Economic Review 90(5):1160–1183

Bjorvatn K, Coniglio ND (2012) Big push or big failure? On the effectiveness of industrialization policies for economic development. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 26(1):129–141

Cantore N, Clara M, Lavopa A, Soare C (2017) Manufacturing as an engine of growth: which is the best fuel? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 42:56–66

Caselli F, Coleman IIWJ (2006) The world technology frontier. American Economic Review 96(3):499–522

Cimoli M, Dosi G (2017) Industrial policies in learning economies. In: Noman A, Stiglitz JE (eds) Efficiency, finance, and varieties of industrial policy, pp 23. Columbia University Press, New York

Cimoli M, Dosi G, Nelson RR, Stiglitz J (2009) Institutions and policies shaping industrial development: an introductory note. In: Cimoli M, Dosi G, Stiglitz JE (eds) Industrial policy and development. The political economy of capabilities accumulation, pp 19–38. Oxford University Press, New York

D’Costa AP (1994) State, steel and strength: structural competitiveness and development in South Korea. The Journal of Development Studies 31 (1):44–81

De Bruecker P, Van den Bergh J, Beliën J, Demeulemeester E (2015) Workforce planning incorporating skills: state of the art. European Journal of Operational Research 243(1):1–16

Dosi G, Nelson RR (1994) An introduction to evolutionary theories in economics. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 4(3):153–172

Dosi G, Fagiolo G, Roventini A (2006) An evolutionary model of endogenous business cycles. Computational Economics 27(1):3–34

El Colegio de México (2018) Desigualdades en méxico 2018 https://desigualdades.colmex.mx/informe-desigualdades-2018.pdf

Fatas-Villafranca F, Jarne G, Sanchez-Choliz J (2009) Industrial leadership in science-based industries: a co-evolution model. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 72(1):390–407

Franck R, Galor O (2015) The complementary between technology and human capital in the early phase of industrialization. Technical report. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 5485

Greenwald B, Stiglitz JE (2013) Industrial policies, the creation of a learning society, and economic development. In: Stiglitz JE, Lin JY (eds) The industrial policy revolution I, The role of government beyond ideology, pp 43–71. Palgrave Macmillan

Grimm M, Knorringa P, Lay J (2012) Constrained gazelles: High potentials in West Africa’s informal economy. World Development 40(7):1352–1368

Haraguchi N, Martorano B, Sanfilippo M (2019) What factors drive successful industrialization? Evidence and implications for developing countries. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 49:266–276

Hausmann R, Rodrik D (2006) Doomed to choose: industrial policy as predicament. Technical report. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

Hofbauer J, Sigmund K, et al. (1998) Evolutionary games and population dynamics. Cambridge University Press

Hopp WJ, Tekin E, Van Oyen MP (2004) Benefits of skill chaining in serial production lines with cross-trained workers. Management Science 50 (1):83–98

Kreickemeier U, Wrona J (2020) Industrialisation and the big push in a global economy. Technical report

Krugman P (1992) Toward a counter-counterrevolution in development theory. The World Bank Economic Review 6(suppl_1):15–38

Lane N (2020) The new empirics of industrial policy. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 20(2):209–234

Lucas E. JR (1988) On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics 22(1):3–42

Mendoza-Palacios S, Mercado A (2021) A note on the big push as industrialization process. In: Mendoza-Palacios S, Mercado A (eds) Games and evolutionary dynamics: selected theoretical and applied developments, pp 153–169. El Colegio de México

Mowery DC, Nelson RR (1999) Sources of industrial leadership: studies of seven industries. Cambridge University Press

Murphy KM, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1989) Industrialization and the big push. Journal of Political Economy 97(5):1003–1026

Nelson RR, Winter SG (2009) An evolutionary theory of economic change. Harvard University Press

Pritchett L (2006) Does learning to add up add up? The returns to schooling in aggregate data. In: Hanushek E, Welch F (eds) Handbook of the economics of education, vol 1, pp 635–695. Elsevier

Reinhard K, Osburg T, Townsend R (2008) The sponsoring by industry of universities of cooperative education: a case study in Germany. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 9(1):1

Rodrik D (1995) Getting interventions right: how South Korea and Taiwan grew rich. Economic Policy 10(20):53–107

Rosenstein-Rodan PN (1943) Problems of industrialisation of Eastern and South-eastern Europe. The Economic Journal 53(210/211):202–211

Sanchez-Carrera E (2019) Evolutionary dynamics of poverty traps. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 29(2):611–630

Sandholm WH (2010) Population games and evolutionary dynamics. MIT Press

Sternberg R, Litzenberger T (2004) Regional clusters in Germany–their geography and their relevance for entrepreneurial activities. European Planning Studies 12(6):767–791

Szirmai A, Verspagen B (2015) Manufacturing and economic growth in developing countries, 1950–2005. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 34:46–59

Trindade V (2005) The big push, industrialization and international trade: the role of exports. Journal of Development Economics 78(1):22–48

Uzawa H (1964) Optimal growth in a two-sector model of capital accumulation. The Review of Economic Studies 31(1):1–24

Wood A (2017) Variation in structural change around the world, 1985–2015: patterns causes and implications

Yamada M (1999) Specialization and the big push. Economics Letters 64(2):249–255

Funding

Work partially supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT-México) under grant Ciencia Frontera 2019-87787.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Stability Analysis

To study the stability of the dynamic system (36)-(37), we will analyze the characteristic polynomial \(f(\epsilon )=\det (A-\epsilon I)\), where 𝜖 = (𝜖1, 𝜖2), I is the 2 × 2-identity matrix and A is the matrix

where

1.1 1.1 Steady State (0, 0)

In this case

where

By (42), πμ(0, 0) < 0. In this case

which implies that the steady state (0, 0) is an attractor.

1.2 1.2 Steady State (0,1)

For this steady state

where

We have that

which implies that the steady state (1, 0) is a repeller if (43) is satisfied, and it is a saddle if (43) is not satisfied.

1.3 1.3 Steady State (1, 0)

In this case

where

Since (42) is satisfied, then πμ(1, 0) > 0. Moreover

Given πμ(1, 0) > 0, if (35) is not satisfied we have that the steady state (0,1) is an attractor. If (35) is satisfied, then it is a saddle.

1.4 1.4 Steady state (1,1)

For this steady state

where

then πμ(1, 1) > 0. We have that

where πμ(1, 1) > 0. Therefore, the steady state (0,1) is a saddle if (35) is not satisfied, and it is an attractor if (35) is satisfied.

1.5 1.5 Steady State \((\lambda _{\mu _{0}^{*}}, 0)\)

Consider \(\lambda _{\mu _{0}^{*}}\) as in (44). In this case

where

The roots of the characteristic polynomial f(𝜖) are

where 𝜖1 > 0. If (35) is not satisfied, then 𝜖2 < 0. In the other case, i.e., if (35) is satisfied, then it is not possible to determine the sign of 𝜖2. Therefore if (35) is not satisfied, then \((\lambda _{\mu _{0}}^{*}, 0)\) is saddle; in the other case, we only know that it is unstable.

1.6 1.6 Steady State \((\lambda _{\mu _{1}^{*}},1)\)

Consider \(\lambda _{\mu _{1}^{*}}\) as in (45), this steady state does not exist if \(\lambda _{\mu _{1}^{*}}\) is not positive. If \(\lambda _{\mu _{1}^{*}}>0\), then

where

The roots of the characteristic polynomial f(𝜖) are

where 𝜖1 > 0. If (35) is not satisfied, then 𝜖2 > 0. If (35) is satisfied, then it is not possible to determine the sign of 𝜖2. Therefore if (35) is not satisfied, then \((\lambda _{\mu _{1}}^{*},1)\) is repeller; in the other case, we only know that it is unstable.

1.7 1.7 Steady State \((\lambda _{\mu }^{*},\gamma _{h}^{*})\)

Consider \(\lambda _{\mu }^{*}\) and \(\gamma _{h}^{*}\) as (46) and (47), respectively. In this case

where

The roots of the characteristic polynomial f(𝜖) of A as in (48) are

with

Since tr(A) > 0, then \((\lambda _{m}u^{*},\gamma _{h}^{*})\) is not a stable steady state. Therefore \((\lambda _{\mu }^{*},\gamma _{h}^{*})\) is unstable, but it is not possible to determine their classification.

Appendix 2: Comparative Statics of λ μ in the Steady States

1.1 2.1 Parameter in Table 2

Consider the values of \(\lambda _{\mu _{0}}^{*},~ \lambda _{\mu _{1}}^{*},\) and \(\lambda _{\mu }^{*}\), as in (44), (45), and (46), respectively.

-

(i) Partial derivatives of λμ with respect to σ:

$$ \begin{array}{@{}rcl@{}} {\partial\lambda_{\mu_{0}}^{*}\over \partial\sigma}&=&0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu_{1}}^{*}\over \partial\sigma}&=&{(w_{\mu}+\omega)c \over (w_{\mu}+\omega)- w_{\tau}}{\kappa L\over NF}>0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu}^{*}\over \partial\sigma}&=& 0. \end{array} $$ -

(ii) Partial derivatives of λμ with respect to c:

$$ \begin{array}{@{}rcl@{}} {\partial\lambda_{\mu_{0}}^{*}\over \partial c}&=&{w_{\mu} \over (w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})} {L\over NF}>0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu_{1}}^{*}\over \partial c}&=&{(w_{\mu}+\omega)\sigma\over (w_{\mu}+\omega)- w_{\tau}}{\kappa L\over NF}>0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu}^{*}\over \partial c}&=&0. \end{array} $$ -

(ii) Partial derivatives of λμ with respect to F:

$$ \begin{array}{@{}rcl@{}} {\partial\lambda_{\mu_{0}}^{*}\over \partial F}&=&{(w_{\tau}-w_{\mu} c) \over (w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})} {L\over NF^{2}}>0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu_{1}}^{*}\over \partial F} &=&{w_{\tau}-(w_{\mu}+\omega)c\sigma \over (w_{\mu}+\omega)- w_{\tau}}{\kappa L\over NF^{2}}>0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu}^{*}\over \partial F}&=&0. \end{array} $$ -

(ii) Partial derivatives of λμ with respect to N:

$$ \begin{array}{@{}rcl@{}} {\partial\lambda_{\mu_{0}}^{*}\over \partial N}&=&{(w_{\tau}-w_{\mu} c) \over (w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})} {L\over N^{2}F}>0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu_{1}}^{*}\over \partial N} &=&{w_{\tau}-(w_{\mu}+\omega)c\sigma \over (w_{\mu}+\omega)- w_{\tau}}{\kappa L\over N^{2}F}>0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu}^{*}\over \partial N}&=&0. \end{array} $$

1.2 2.2 Parameter in Table 3

Consider the values of \(\lambda _{\mu _{0}}^{*},~ \lambda _{\mu _{1}}^{*},\) and \(\lambda _{\mu }^{*}\), as in (44), (45), and (46), respectively.

-

(i) Partial derivatives of λμ with respect to L:

$$ \begin{array}{@{}rcl@{}} {\partial\lambda_{\mu_{0}}^{*}\over \partial L}&=&-{(w_{\tau}-w_{\mu} c) \over (w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})} {1\over NF} <0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu_{1}}^{*}\over \partial L}&=&-{w_{\tau}-(w_{\mu}+\omega)c\sigma \over (w_{\mu}+\omega)- w_{\tau}}{\kappa \over NF}<0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu}^{*}\over \partial L} &=&0. \end{array} $$ -

(ii) Partial derivatives of λμ with respect to κ:

$$ \begin{array}{@{}rcl@{}} {\partial\lambda_{\mu_{0}}^{*}\over \partial \kappa}&=&0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu_{1}}^{*}\over \partial \kappa}&=&-{w_{\tau}-(w_{\mu}+\omega)c\sigma \over (w_{\mu}+\omega)- w_{\tau}}{L\over NF}<0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu}^{*}\over \partial \kappa} &=&{-w_{\tau} \over \kappa\omega -(1-\kappa)(w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})}-{(1-\kappa)w_{\tau} (w_{\mu}+\omega -w_{\tau} )\over \big(\kappa\omega -(1-\kappa)(w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})\big)^{2}}<0. ~~(*) \end{array} $$(*) If \(\lambda _{\mu _{0}}^{*}>0\) we need that κω − (1 − κ)(wμ − wτ) > 0, which implies that \({\lambda _{\mu }^{*}\over \partial \kappa }<0\).

-

(iii) Partial derivatives of λμ with respect to wμ:

$$ \begin{array}{@{}rcl@{}} {\partial\lambda_{\mu_{0}}^{*}\over \partial w_{\mu}}&=&{{-w_{\tau}\left( 1-(1-c){L\over NF}\right) }\over (w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})^{2}}>0~~(*); \\ {\lambda_{\mu_{1}}^{*}\over \partial w_{\mu}}&=&{{-w_{\tau}\left( 1-(1-c\sigma){\kappa L\over NF}\right) }\over (w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})^{2}}>0~~(**); \\ {\lambda_{\mu}^{*}\over \partial w_{\mu}} &=&{(1-\kappa)^{2} w_{\tau} \over\big(\kappa\omega -(1-\kappa)(w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})\big)^{2}}>0. \end{array} $$(*) If (43) is satisfied then

$$(1-c){L\over NF}>\left( 1-{w_{\mu} c \over w_{\tau}} \right) {L\over NF}>1,$$which implies that \({\partial \lambda _{\mu _{0}}^{*}\over \partial w_{\mu }}>0\).

(**) If (43) is satisfied then

$$(1-c\sigma){\kappa L\over NF}>\left( 1-{w_{\mu} c \over w_{\tau}} \right) {L\over NF}>1,$$which implies that \({\partial \lambda _{\mu _{1}}^{*}\over \partial w_{\mu }}>0\).

-

(iii) Partial derivatives of λμ with respect to ω:

$$ \begin{array}{@{}rcl@{}} {\partial\lambda_{\mu_{0}}^{*}\over \partial \omega}&=&0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu_{1}}^{*}\over \partial \omega}&=&{{-w_{\tau}\left( 1-(1-c\sigma){\kappa L\over NF}\right) }\over (w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})^{2}}>0; \\ {\lambda_{\mu}^{*}\over \partial \omega} &=&{-(1-\kappa)\kappa w_{\tau} \over \big(\kappa\omega -(1-\kappa)(w_{\mu}-w_{\tau})\big)^{2}}<0; \\ \end{array} $$

1.3 2.3 Parameter of Figures

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mendoza-Palacios, S., Berasaluce, J. & Mercado, A. On Industrialization, Human Resources Training, and Policy Coordination. J Ind Compet Trade 22, 179–206 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-021-00376-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-021-00376-2

Keywords

- Industrialization policy

- Coordination

- Technological change

- Choice of technology

- Push strategies

- Evolutionary dynamics