Abstract

Noise is one of a wide range of disturbances associated with human activities that have been shown to have detrimental impacts on a wide range of species, from montane regions to the deep marine environment. Noise may also have community-level impacts via predator–prey interactions, thus jeopardising the stability of trophic networks. However, the impact of noise on freshwater ecosystems is largely unknown. Even more so is the case of insects, despite their crucial role in trophic networks. Here, we study the impact of underwater noise on the predatory functional response of damselfly larvae. We compared the feeding rates of larvae under anthropogenic noise, natural noise, and silent conditions. Our results suggest that underwater noise (pooling the effects of anthropogenic noise and natural noise) decreases the feeding rate of damselflies significantly compared to relatively silent conditions. In particular, natural noise increased the handling time significantly compared to the silent treatment, thus reducing the feeding rate. Unexpectedly, feeding rates under anthropogenic noise were not reduced significantly compared to silent conditions. This study suggests that noise per se may not necessarily have negative impacts on trophic interactions. Instead, the impact of noise on feeding rates may be explained by the presence of nonlinearities in acoustic signals, which may be more abundant in natural compared to anthropogenic noise. We conclude by highlighting the importance of studying a diversity of types of acoustic pollution, and encourage further work regarding trophic interactions with insects using a functional response approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human activities have exerted sub stantial pressures on a wide range of ecosystems, from montane regions to the deep marine environment. Many such impacts have been categorised, evaluated, and quantified in great detail (Sala et al. 2000). However, many such studies have focused on those threats that are easiest to quantify and study, based on broad assessments of community diversity and structure with and without the threat, such as habitat fragmentation (Fahrig 2003) and climate change (e.g. Chen et al. 2011). However, other stressors do not offer such clear records of their impacts on the environment.

This is the case of noise pollution. While some research into the impacts of noise on animals has achieved a high profile, particularly research carried out on cetaceans (Weilgart 2007) and in urban birds (Slabbekoorn and Peet 2003), research is only just beginning to explore the wider impacts on ecosystems. Additionally, at an individual level, anthropogenic noise can have considerable anatomical, physiological, and behavioural impacts (Kight and Swaddle 2011; Kunc et al. 2016). For example, exposure to road traffic noise reduced foraging and increased vigilance significantly in the prairie dog Cynomys ludovicianus (Shannon et al. 2014). Even though some species have developed mechanisms to cope with noise disturbance (Fuller et al. 2007; Halfwerk and Slabbekoorn 2009; Parris et al. 2009), the potential of anthropogenic noise to impact the conservation of wildlife populations (Slabbekoorn and Ripmeester 2008; Brumm 2010; Chan and Blumstein 2011; Aguilar de Soto 2016), as well as the wellbeing of human populations (WHO 2011), is nonetheless concerning.

In aquatic environments, the impact of noise is even stronger given the fact that sound waves travel nearly five times quicker in water than through air (USA Office of Scientific Research Development and National Defense Research Committee 1946). In marine ecosystems, acoustic masking due to anthropogenic noise can impair the reception of information through various “acoustic spaces”, such as echolocation, intraspecific communication, predator avoidance and prey detection (Clark et al. 2009). However, little is known about the impact of anthropogenic noise on freshwater habitats. Freshwater ecosystems account for 0.01% of global water and yet support almost 6% of all described species (Dudgeon et al. 2006) and provide a wide range of ecosystem services (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005). However, these habitats are also susceptible to various sources of noise, most notably boats in canals, lakes, and rivers. Only a few studies have investigated the impact of noise on freshwater species, e.g. foraging efficiency in sticklebacks (Purser and Radford 2011; Voellmy et al. 2014) and European eels (Simpson et al. 2015). Such studies show the impacts of noise may go beyond single species and have community-level effects via trophic interactions. Noise may disrupt predatory mechanisms in various ways, either by (a) inducing stress (Simpson et al. 2015), (b) masking the acoustic cues produced by predators and/or prey, thus complicating detection (Siemers and Schaub 2011), (c) inducing attention shifts on the predator (Purser and Radford 2011), or (d) by compromising antipredator behaviour in the prey, which may in turn increase predation risk (Simpson et al. 2015). Possible disturbances in predator–prey interactions in freshwater ecosystems via anthropogenic noise may lead to sudden shifts in predator and/or prey populations and compromise the stability of trophic networks. It is essential to understand the effects of noise on predator–prey interactions in order to implement mitigation programmes for the management and conservation of species and ecosystems (Chan and Blumstein 2011).

However, the impact of noise on insects has been largely overlooked (Morley et al. 2014), despite the fact that insects are hugely diverse and comprise the vast majority of species worldwide (Mora et al. 2011) and thus have a crucial role in trophic networks (Schoenly et al. 1991). The impacts of underwater noise on aquatic insects are likely to have a stronger effect at a community level compared to vertebrates in freshwater ecosystems due to the great contribution of aquatic invertebrates to a wide range of ecosystem functions such as controlling algal populations, shredding leaf litter to form fine particulate organic matter (FPOM), promoting wood decomposition, and controlling other macroinvertebrate populations, e.g. mosquitoes (Wallace and Webster 1996). Moreover, in the case of semi-aquatic insects, the potential impacts of noise in freshwater habitats can also impact terrestrial ecosystems through cascading trophic interactions across ecosystem boundaries (Knight et al. 2005).

A useful method for predicting the ecological impacts of predator–prey interactions is the functional response (Dick et al. 2014). The functional response was first described by Holling (1959) and is defined as the relationship between a predator’s feeding rate and the prey density. This method predicts three parameters which dictate the amount of prey eaten according to prey density: the attack rate (also called searching time or attack coefficient), the handling time, and the total time available for predation. The attack rate is defined as “the instantaneous rate of discovery”, whereas the handling time is referred to as the time taken to process the prey, including all stages of the predatory sequence and the digestive pause. In other words, the time elapsing from the pursuit of one prey to the next (Holling 1959). Functional responses can be classified into three types: type I assumes a linear increase of number of prey eaten with prey density; type II assumes a maximum number of prey eaten as prey density increases according to a satiation point, where the curves reaches an asymptote; type III is similar to the aforementioned, except the number of prey eaten is low at lower prey densities, forming a sigmoid curve (Holling 1959). The functional response approach takes into account important ecological factors such as prey density, searching time and satiation levels, which makes it more realistic compared to other methods for estimating the relationship between predator and prey populations. Most importantly, this approach explicitly considers demographic consequences for prey populations (Dick et al. 2014). Making predictions about outcomes at a population level is key for understanding ecological processing across trophic networks and to address conservation issues (Brumm 2010; Morley et al. 2014). Hence, using the functional response approach may help estimate fluctuations on prey populations of conservation interest (e.g. Watari et al. 2013).

This study aims to investigate the impact of natural and anthropogenic underwater noise on predator–prey interactions in freshwater ecosystems using a functional response approach in damselfly larvae, which are aquatic predatory insects. Damselflies (Zygoptera) represent a semi-aquatic taxon with an aquatic larval phase and a terrestrial adult phase. Larval damselflies are found in lotic and lentic habitats feeding on smaller invertebrates such as Daphnia (Thompson 1978a) and, at the same time, are prey of larger predators (Martins et al. 2010). Damselfly larvae can locate prey using their compound eyes and mechanoreceptors—such as the tarsal hairs and antennae—to detect the vibrations produced by the prey (Vasserot 1957). Hence, noisy environments can potentially interfere with their mechanism for prey detection.

Our two hypotheses—which are not mutually exclusive—are: (a) underwater noise causes larvae to take longer to detect their prey, therefore decrease the attack rate and the total prey consumed; (b) underwater noise increases handling time, thus decreasing the total prey consumed.

Materials and methods

Study species

The model species selected for this study is Ischnura elegans (Fig. 1). I. elegans is one of the most common zygopteran species in Europe, is found mostly in lentic habitats or very slow-moving waters such as canals, and can tolerate high levels of eutrophication and salinity, although it cannot inhabit acidic sites such as bogs (Dijkstra and Lewington 2006; Dow 2010). I. elegans is univoltine across most of its range, with some evidence of semivoltinism in more northerly regions (Thompson 1978b), and can occupy habitats with and without fish (McPeek 1998). This species was chosen due to its prevalence in disturbed, urban environments where noise may be a stressor (Goertzen and Suhling 2013).

Collection of adults and larvae rearing

To control for phenotypic plasticity, we conducted a common garden rearing experiment. We obtained I. elegans eggs from field-caught adult females from sites in an urban to rural gradient (see Table S1 in Supplementary Information) during July–August 2015. Once the eggs hatched, the larvae were reared at 20 °C at a photoperiod of 14L:10D with aerated tap water and fed with Artemia sp. and Daphnia magna ad libitum.

Experimental design

For the functional response experiments, three treatments were used: (1) anthropogenic noise, recorded from the diesel engine of a narrowboat in the Leeds-Liverpool canal, UK (53.794°N, 1.559°W) with an underwater recorder (condenser hydrophone connected to a Zoom H1 portable digital recorder); (2) natural noise, represented by water flowing on a rocky river (track “river-6.wav” downloaded from http://www.soundjay.com/river-sounds-1.html), and (3) the control treatment, conducted in silence. All audio stimuli were normalised and saved in WAV format with 32-bit floating point (Fig. 2a, b). Spectral power density was analysed in Audacity 2.1.0 (http://www.audacityteam.org/) using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) with Hann evaluation window, FFT size 512, averaged from a 20 s sample of each recording (Fig. 2c).

Properties of the audio cues used in the functional response experiment. a Segment of 5 s of the audio cue used in the anthropogenic treatment, recorded from the diesel engine of a narrowboat; b segment of the audio cue used in the natural treatment, represented by a rocky river, also 5 s; c segment of the sound levels in the Leeds-Liverpool Canal with no boats passing by, also 5 s; d power spectral density of the original audio cues used in the anthropogenic and natural treatments, the re-recordings of the original audio cues in the fish tank used as part of the experimental setup, the sound levels of the canal with no boats, and the recording of the sound levels in the silent (control) treatment

Prior to the experiments, larvae were selected based on their head width to standardise size, since larger larvae are known to have higher predation rates (Thompson 1975). Only larvae with head width of 2.5–3.1 mm (mean = 2.86 mm ± 0.013 SE) were used in the experiments, which were most likely to be on the 11th instar (Thompson 1975, 1978b). The larvae selected were starved for 48 h to empty their gut before the experiment (Thompson 1975).

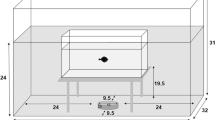

During the experiments, the larvae were transferred to individual meshed cylindrical containers (0.5 mm mesh size, 6 cm diameter, 14 cm long) with a wooden stick for the larva to perch to reduce stress, inside a 28 L fish tank (24 × 39 × 30 cm) covered on all sides in a 5 cm layer of polystyrene to isolate against noise. The tank was filled with 9 L of aged tap water. Two sound transducers (Adin B1BT 10W vibration speakers) were laid on two opposite sides of the tank to produce the acoustic stimulus synchronously (Fig. 3). Sound transducers produce vibration alongside playing the tracks to recreate the effect of boat passage. Even though the transducers were located outside the tank, which may limit considerably the particle motion produced by sound waves, the vibrations produced by the transducers are transferred to the tank walls and, subsequently, the water, thus facilitating to a certain extent the particle motion alongside the pressure waves. Larvae were fed with Daphnia (the prey model). Size of Daphnia was also controlled: only Daphnia that were able to pass through a 1.4 mm Endecotts Test Sieve, but not a 1 mm mesh sieve were used in the experiments.

Different densities of Daphnia were placed inside the meshed containers alongside the larvae. Prey densities were 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, and 50 individual Daphnia. Sample sizes per prey density in each treatment ranged from 4 to 7 due to the death of some experimental animals (see Table S2 in Supplementary Information). Each larva was only used once, so animals represent individual, independent replicates. Considering the transducers were located on the sides of the tank, the strength of the stimuli varied spatially within the tank according to the distance from the transducers, so the position of the larvae inside the experimental setup can have an influence on the perception of noise and the resulting predation response. In order to avoid any bias in the analysis due to this issue, the position of each larvae and prey density replicate was randomised prior to running the experiments. Each experiment was left running for 24 h in an incubator at 20 °C in the dark. Using the incubator also ensured that the temperature was constant, which is a crucial driver of the functional response of odonates (Thompson 1978b), and even though the incubator might have produced additional noise, this noise was consistent across all experiments. The experiment was left in the dark for two reasons: (a) to ensure that prey were not detected visually, but merely by the vibrations produced by the prey, (b) to avoid photic effects in the water that may cause behavioural changes in Daphnia (Thompson 1975). The acoustic stimuli were looped over the 24 h, except in the control treatment where there was no sound produced. The sound transducers were left in place during the control treatment. After the 24 h-period, the larvae were removed and the Daphnia counted. To account for the fact that damselfly larvae engage in “wasteful killing” (Johnson et al. 1975) or also called “partial consumption” (Paterson et al. 2015), the Daphnia that had more than 50% of their bodies missing were considered as “eaten”, whilst the ones that had less than 50% missing were recorded as a result of “wasteful killing”.

Statistical analysis

We performed two separate analyses: first, we tested the differences in the attack rates and the handling times with and without acoustic stimuli by pooling the data from the anthropogenic noise and natural noise treatments and compared the coefficients against the control (silence) treatment. In the second analysis, we compared the attack rates and the handling times of each treatment explicitly, that is, anthropogenic noise, natural noise, and control (silence) treatments. The statistical analysis was performed using the frair package (Pritchard 2014) in R 3.0.2 (R Core Team 2013). The functional response of I. elegans larvae has been previously described as type II (Thompson 1975, 1978b). Given that the prey were not replaced during the experiment, the attack rates and handling times were calculated using Rogers’ type II formula (Rogers 1972):

where N a number of prey eaten, N 0 prey density, T total time prey are exposed to predation, a attack rate, and h handling time.

However, the frair package utilises maximum likelihood estimation within the bbmle package (Bolker and R Development Core Team 2014) and a modified version of Eq. (1) with Lambert’s W function (Bolker 2008) to make the equation solvable:

The fitted curves were bootstrapped to visualise variability (n = 999), and both the attack rate and handling time were compared between treatments using indicator variables (Juliano 2001) using the function “frair_compare” in the frair package. The “indicator variable” approach only allows pairwise comparisons between groups (Juliano 2001), but this approach has been widely used in functional response studies (e.g. Paterson et al. 2015; Taylor and Dunn 2016).

To ensure that all individuals considered had a stable feeding rate, we conducted an a posteriori analysis by identifying and eliminating potential outliers. In order to do so, the residuals were obtained from the fitted functional response curve. All residuals that were below the first quantile—1.5 interquartile range (IQR) or above the third quantile + IQR were excluded, leading to the exclusion of three data points. Once all potential outliers were removed, the attack rates and handling times were recalculated using the same procedure previously described and the functional response curves were refitted.

Results

As described by Thompson (1975, 1978b), the functional response of I. elegans in all treatments was type II (Fig. 4). In the first analysis, we compared the control (silence) treatment against the pooled noise treatments to evaluate the effect of noise per se on feeding. The functional response of I. elegans had a lower maximum feeding rate with noise (1/hT = 10.6 prey·day−1; Fig. 4a) compared to the feeding rate in silent conditions (1/hT = 16.7 prey·day−1; Fig. 4a). Specifically, the handling time increased significantly with noise (Table 1, Fig. 5a), whereas the difference in the attack rates with noise and no noise was not significant (Table 1; Fig. 5a). These results support our hypothesis that underwater noise decreases the feeding rate of I. elegans, particularly by increasing the handling time.

Fitted functional response curves from all the experiments obtained from the frair package (Pritchard 2014), comparing a the control treatment (silence) against noise (grouping anthropogenic and natural noise treatments), and b the control treatment against the anthropogenic and natural noise treatments. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals

Estimates of the attack rates and the handling times in each treatment, comparing a control treatment (silence) against noise (grouping anthropogenic and natural noise treatments), and b control treatment (silence) against anthropogenic and natural noise treatments. Letters represent significant difference. Error bars represent bootstrapped studentized 95% confidence intervals

In the second analysis, we compared the control (silence) treatment to each of the two different types of acoustic stimuli (anthropogenic and natural). The outcomes differed when the functional responses of I. elegans were analysed under different types of noise. The maximum feeding rate of I. elegans in the anthropogenic noise treatment was lower than the maximum feeding rate in the control treatment (anthropogenic noise: 1/hT = 12.0 prey·day−1; control: 1/hT = 16.7 prey·day−1), but neither the attack rate nor the handling time in the anthropogenic noise treatment were significantly different from the control treatment (Table 1, Fig. 5b). Unexpectedly, the natural noise treatment showed the lowest feeding rate of all treatments (1/hT = 9.4 prey·day−1). In particular, the handling time in the natural noise treatment was significantly higher than the control and the anthropogenic noise treatment (Table 1, Fig. 5b). The attack rates were not significantly different among treatments (Table 1, Fig. 5b).

Discussion

The results from this study suggest that, in general, the presence of acoustic stimuli decreased the number of prey eaten compared to silent conditions even at high prey densities. The results also suggest that the attack rate did not change with underwater noise, but instead the handling time increased, thus decreasing the feeding rate of the larvae in the presence of noise. The finding supports our general hypothesis that noise interferes with feeding behaviour. However, we found that natural and anthropogenic noise had different outcomes: natural noise decreased the number of prey eaten by the larvae significantly, while anthropogenic noise had no significant effect. These results suggest that I. elegans larvae do not take longer to detect or process their prey with anthropogenic noise, which therefore does not decrease the amount of prey eaten compared to silent conditions. However, the number of prey eaten under natural noise is significantly less than in silent conditions. Specifically, we found increased handling time with natural noise, which suggests that the larvae take longer to catch and/or process their prey compared to silent conditions. No difference in attack rate was found in any of the treatments.

The fact that anthropogenic noise does not affect the attack rate or handling time suggests that either the I. elegans larvae and/or the Daphnia—predator and prey in this study—can tolerate anthropogenic noise. This is the first evidence of aquatic macroinvertebrates being tolerant to anthropogenic noise. However, it is not possible to ascertain the drivers of this response from the data obtained in this study; more research is needed to discover the mechanism driving this tolerance to anthropogenic noise. Paradoxically, the acoustic stimuli used in the natural noise treatment had a negative impact on the functional response of the larvae; this type of noise was found to decrease the number of prey eaten due to increased handling time. To our knowledge, no other studies have found natural noise to have detrimental effects on the predation rate of any organism, although other studies use “ambient” noise as the baseline to compare the effects against anthropogenic noise (e.g. Wale et al. 2013a, b), instead of comparing noise vs. no noise. While I. elegans is mostly found in lentic habitats such as ponds, the species is also abundant around running waters (Dijkstra and Lewington 2006; Dow 2010). The greater prevalence in lentic habitats may explain why natural noise had a significant impact on the amount of prey eaten by larvae compared to the low noise treatment that may be representative of the preferred still water habitat.

Another plausible explanation as to why natural noise had a greater effect than anthropogenic noise on the functional response of I. elegans is due to the presence of nonlinearities in the audio cues used in the experiment. The power spectrum of the anthropogenic noise recorded showed high-amplitudes (maximum − 11.55 dB) only at low frequencies (maximum 3 KHz), and then the amplitude decreased drastically (− 54 dB) and became relatively stable at higher frequencies. The stimuli used in the natural noise treatment, on the other hand, had lower amplitude levels (maximum − 51.1 dB) compared to the anthropogenic noise, but the amplitude levels were highest at low frequencies (maximum 3 KHz) and then decreased gradually as the frequencies increased (see Fig. 2). This can be interpreted as natural noise having high amplitude levels at low frequencies with some degree of nonlinearity at different frequencies compared to anthropogenic noise. A wide range of invertebrates have adapted to detect particle motion at frequencies below 1 KHz (Morley et al. 2014), and stimuli of higher frequencies have been shown to be less relevant in other animals such as fish (Popper and Fay 1993; Fay and Popper 2012). However, nonlinearities in acoustic phenomena have been shown to increase unpredictability and result in a heightened behavioural response in meerkats (Townsend and Manser 2011; Karp et al. 2014), marmots (Blumstein and Récapet 2009), and red deers (Reby and Charlton 2012). An accessible example of the difference between a simple and nonlinear acoustic signal is in the vocalization of primates, ranging from “coo” calls (relatively pure tones with minimal noise) through to nonlinear sounds such as “screams” (highly complex sounds produced with subharmonics and deterministic chaos; see Fig. 1 in Fitch et al. (2002) for an example). This is in accordance with the ‘unpredictability hypothesis’, which suggests that nonlinearities prevent habituation and may induce fear, since “unfamiliar” noises (i.e. nonlinearities) can be perceived as a threat, e.g. a predator (Blesdoe and Blumstein 2014; Karp et al. 2014). In this study, our recording of anthropogenic noise is more predictable than natural noise, despite having high amplitude levels at low frequencies, thus it is more likely that the damselfly larvae become habituated to anthropogenic noise, whereas nonlinearities in natural noise may be misconceived as a threat.

One can argue that natural noise can mask the vibrations produced by the prey, particularly since in Calopteryx splendens—another zygopteran—the optimal stimulus is a sequence of stochastic, small-amplitude pressure waves resembling those produced by Daphnia (Vasserot 1957), which is similar to the nonlinear, low-amplitude pattern found in natural noise. However, this seems unlikely considering that masking the vibrations produced by prey would affect the attack rate rather than the handling time, as was found in the present study. According to Holling (1959), the handling time includes catching, processing, and digesting the prey. We speculate the impact of natural noise can occur on any of these phases through one of the following mechanisms: (a) natural noise distracts the predator and thus complicates the catchment and/or processing of prey, as has been found in European eels (Purser and Radford 2011); (b) natural noise increases the movement of prey (frequency or distance of movement), therefore delaying the catchment of prey; (c) natural noise induces stress via hormones, which may alter the predator’s metabolism and prolong the processing of food (Kight and Swaddle 2011). Additionally, it is important to mention only one audio file of each stimuli was used per treatment, so it is impossible to separate the effects of the stimuli used from the noise types per se. However, more studies are needed to unveil the underlying mechanism driving this response.

The results from this study provide evidence that underwater noise may impose a threat to the stability of trophic networks. I. elegans is known to feed on oligochaete worms, chironomids and other dipterans, coleopteran larvae, copepods, daphniids, isopods, ostracods, ephemeropterans, and even other zygopterans (Thompson 1978a). Considering underwater noise reduces the maximum feeding rate, then it is within reason to expect declines in the strength of trophic link between damselflies and these prey taxa in noisy areas—which may or may not be associated with human activities. This has considerable impacts on population dynamics of the predator (I. elegans in this case) and prey, which may also have substantial implications on the management and conservation of freshwater biodiversity (Chan and Blumstein 2011).

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that other sources of noise, such as noises generated in complex flowing water environments, may have even a higher impact on aquatic macroinvertebrates and can be a factor in determining the stability of trophic interactions. This study highlights the importance of studying the impact of not only anthropogenic noise, but also natural sources of noise.

To conclude, this study has effectively shown that underwater noise can significantly alter predator–prey interactions. However, anthropogenic noise may not necessarily have a negative impact on predator–prey interactions, but rather the characteristics of the type of noise itself. Additionally, this is the first study to our knowledge that explores the role of noise in the functional response of an aquatic invertebrate predator and compares natural and anthropogenic noise. However, further research is encouraged and needed to discover the underlying mechanisms of this response, and should focus on the characteristics of environmental noise within the context of prey capture to understand the effects on conservation of biodiversity.

References

Aguilar de Soto N (2016) Peer-reviewed studies on the effects of anthropogenic noise on marine invertebrates: from scallop larvae to giant squid. In: Popper A, Hawkins A (eds) The effects of noise on aquatic life II. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, vol 875. Springer, New York, NY, pp 17–26

Blesdoe EK, Blumstein DT (2014) What is the sound of fear? Behavioral responses of white-crowned sparrows Zonotrichia leucophrys to synthesized nonlinear acoustic phenomena. Curr Zool 60:534–541

Blumstein DT, Récapet C (2009) The sound of arousal: the addition of novel non-linearities increases responsiveness in marmot alarm calls. Ethology 115:1074–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2009.01691.x

Bolker BMB (2008) Ecological models and data in R. Princeton University Press, New Jersey

Bolker B, R Development Core Team (2014) bbmle: tools for general maximum likelihood estimation

Brumm H (2010) Anthropogenic noise: implications for conservation. In: Breed MD, Moore J (eds) Encyclopedia of animal behavior, vol 3. Elsevier Science, pp 89–93

Chan AAYH, Blumstein DT (2011) Attention, noise, and implications for wildlife conservation and management. Appl Anim Behav Sci 131:1–7

Chen I-C, Hill JK, Ohlemuller R et al (2011) Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 333:1024–1026. doi:10.1126/science.1206432

Clark CW, Ellison WT, Southall BL et al (2009) Acoustic masking in marine ecosystems: intuitions, analysis, and implication. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 395:201–222

Dick JTA, Alexander ME, Jeschke JM et al (2014) Advancing impact prediction and hypothesis testing in invasion ecology using a comparative functional response approach. Biol Invasions 16:735–753. doi:10.1007/s10530-013-0550-8

Dijkstra KDB, Lewington R (2006) Field guide to the dragonflies of Britain and Europe: including western turkey and north-western Africa. British Wildlife Publishing, Oxford

Dow RA (2010) Ischnura elegans. IUCN Red List Threat. Species 2010, version 2014.2 e.T165479A6032596. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/165479/0

Dudgeon D, Arthington AH, Gessner MO et al (2006) Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol Rev 81:163–182. doi:10.1017/S1464793105006950

Fahrig L (2003) Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 34:487–515. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132419

Fay RR, Popper AN (2012) Fish hearing: new perspectives from two “senior” bioacousticians. Brain Behav Evol 79:215–217

Fitch WT, Neubauer J, Herzel H (2002) Calls out of chaos: the adaptive significance of nonlinear phenomena in mammalian vocal production. Anim Behav MS 63:407–418

Fuller RA, Warren PH, Gaston KJ (2007) Daytime noise predicts nocturnal singing in urban robins. Biol Lett 3:368–370

Goertzen D, Suhling F (2013) Promoting dragonfly diversity in cities: major determinants and implications for urban pond design. J Insect Conserv 17:399–409. doi:10.1007/s10841-012-9522-z

Halfwerk W, Slabbekoorn H (2009) A behavioural mechanism explaining noise-dependent frequency use in urban birdsong. Anim Behav 78:1301–1307

Holling CS (1959) Some characteristics of simple types of predation and parasitism. Can Entomol 91:385–398. doi:10.4039/Ent91385-7

Johnson DM, Akre BG, Crowley PH (1975) Modeling arthropod predation: wasteful killing by damselfly naiads. Ecology 56:1081–1093. doi:10.2307/1936148

Juliano SA (2001) Nonlinear curve fitting: predation and functional response curves. In: Scheiner SM, Gurevitch J (eds) Design and analysis of ecological experiments. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 178–196

Karp D, Manser MB, Wiley EM, Townsend SW (2014) Nonlinearities in meerkat alarm calls prevent receivers from habituating. Ethology 120:189–196. doi:10.1111/eth.12195

Kight CR, Swaddle JP (2011) How and why environmental noise impacts animals: an integrative, mechanistic review. Ecol Lett 14:1052–1061. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01664.x

Knight TM, McCoy MW, Chase JM et al (2005) Trophic cascades across ecosystems. Nature 437:880–883. doi:10.1038/nature03962

Kunc HP, McLaughlin KE, Schmidt R (2016) Aquatic noise pollution: implications for individuals, populations, and ecosystems. Proc R Soc B 283:20160839

Martins FI, de Souza FL, da Costa HTM (2010) Feeding habits of Phrynops geoffroanus (Chelidae) in an urban river in Central Brazil. Chelonian Conserv Biol 9:294–297. doi:10.2744/CCB-0809.1

McPeek MA (1998) The consequences of changing the top predator in a food web: a comparative experimental approach. Ecol Monogr 68:1–23

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) Ecosystems and human well-being: policy responses. Island Press, Washington, DC

Mora C, Tittensor DP, Adl S et al (2011) How many species are there on earth and in the ocean? PLoS Biol 9:e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127

Morley EL, Jones G, Radford AN (2014) The importance of invertebrates when considering the impacts of anthropogenic noise. Proc R Soc B. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2683

Parris KM, Velik-Lord M, North JMA (2009) Frogs call at a higher pitch in traffic noise. Ecol Soc 14:25

Paterson RA, Dick JTA, Pritchard DW et al (2015) Predicting invasive species impacts: a community module functional response approach reveals context dependencies. J Anim Ecol 84:453–463. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.12292

Popper AN, Fay RR (1993) Sound detection and processing by fish: critical review and major research questions. Brain Behav Evol 41:14–38. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Pritchard D (2014) frair: functional response analysis in R (version 0.4). http://cran.r-project.org/package=frair

Purser J, Radford AN (2011) Acoustic noise induces attention shifts and reduces foraging performance in three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus). PLoS ONE 6:e17478. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017478

R Core Team (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://www.R-project.org/

Reby D, Charlton BD (2012) Attention grabbing in red deer sexual calls. Anim Cogn 15:265–270. doi:10.1007/s10071-011-0451-0

Rogers D (1972) Random search and insect population models. J Anim Ecol 41:369–383. doi:10.2307/3474

Sala OE, Chapin FS III, Armesto JJ et al (2000) Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science 287:1770–1774. doi:10.1126/science.287.5459.1770

Schoenly K, Beaver R, Heumier T (1991) On the trophic relations of insects: a food-web approach. Am Nat 137:597–638

Shannon G, Angeloni LM, Wittemyer G et al (2014) Road traffic noise modifies behavior of a keystone species. Anim Behav 94:135–141

Siemers BM, Schaub A (2011) Hunting at the highway: traffic noise reduces foraging efficiency in acoustic predators. Proc R Soc B 278:1646–1652. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2262

Simpson SD, Purser J, Radford AN (2015) Anthropogenic noise compromises antipredator behaviour in European eels. Glob Chang Biol 21:586–593. doi:10.1111/gcb.12685

Slabbekoorn H, Peet M (2003) Ecology: birds sing at a higher pitch in urban noise. Nature 424:267. doi:10.1038/424267a

Slabbekoorn H, Ripmeester EAP (2008) Birdsong and anthropogenic noise: Implications and applications for conservation. Mol Ecol 17:72–83

Taylor NG, Dunn AM (2016) Size matters: predation of fish eggs and larvae by native and invasive amphipods. Biol Invasions. doi:10.1007/s10530-016-1265-4

Thompson DJ (1975) Towards a predator-prey model incorporating age structure: the effects of predator and prey size on the predation of Daphnia magna by Ischnura elegans. J Anim Ecol 44:907–916. doi:10.2307/3727

Thompson DJ (1978a) The natural prey of larvae of the damselfly, Ischnura elegans (Odonata: Zygoptera). Freshw Biol 8:377–384. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.1978.tb01458.x

Thompson DJ (1978b) Towards a realistic predator-prey model: the effect of temperature on the functional response and life history of larvae of the damselfly, Ischnura elegans. J Anim Ecol 47:757–767. doi:10.2307/3669

Townsend SW, Manser MB (2011) The function of nonlinear phenomena in meerkat alarm calls. Biol Lett 7:47–49. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0537

USA Office of Scientific Research Development, National Defense Research Committee (1946) Principles and applications of underwater sound. Department of the Navy, Headquarters Naval Material Command; (for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt, Print. Off.)

Vasserot J (1957) Contribution a l’etude du comportement de capture des larves de l’odonate Calopteryx splendens. Vie Milieu 8:127–172

Voellmy IK, Purser J, Flynn D et al (2014) Acoustic noise reduces foraging success in two sympatric fish species via different mechanisms. Anim Behav 89:191–198. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.12.029

Wale MA, Simpson SD, Radford AN (2013a) Size-dependent physiological responses of shore crabs to single and repeated playback of ship noise. Biol Lett 9:20121194. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.1194

Wale MA, Simpson SD, Radford AN (2013b) Noise negatively affects foraging and antipredator behaviour in shore crabs. Anim Behav 86:111–118. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.05.001

Wallace JB, Webster JR (1996) The role of macroinvertebrates in stream ecosystem function. Annu Rev Entomol 41:115–139. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.41.010196.000555

Watari Y, Nishijima S, Fukasawa M et al (2013) Evaluating the “recovery level” of endangered species without prior information before alien invasion. Ecol Evol 3:4711–4721. doi:10.1002/ece3.863

Weilgart LS (2007) The impacts of anthropogenic ocean noise on cetaceans and implications for management. Can J Zool 85:1091–1116. doi:10.1139/Z07-101

WHO (2011) Burden of disease from environmental noise: quantification of healthy life years lost in Europe. WHO, Copenhagen

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Robert Holbrook for his useful suggestions in the design of this study, as well as William Fincham and Nigel Taylor for their support during the analysis. GV-J is supported by the National Council of Science and Technology in Mexico (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, CONACYT) through a doctoral studentship. CH was supported by a Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship within the 7th European Community Framework Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Villalobos-Jiménez, G., Dunn, A.M. & Hassall, C. Environmental noise reduces predation rate in an aquatic invertebrate. J Insect Conserv 21, 839–847 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-017-0023-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-017-0023-y