Abstract

As a policy tool aimed at raising parental labor supply, childcare subsidies come with high expectations. Using data from a factorial survey conducted in the City of Bern, Switzerland, we examine whether childcare subsidies reach their goal. Because of the simultaneity of the decision to take up a job and arranging childcare, we experimentally alter hypothetical income (e.g., gross earnings from a job, income from other sources) as well as aspects of the childcare setting including subsidy levels. Using an alternative-specific conditional logit model, we show that subsidies have the expected effect of increasing parents’ labor supply. Moreover, the results from simulations based on the estimated utility function show that varying subsidy levels have different effects on subgroups of parents. Subsidies are especially efficient in raising the labor supply of low-status parents, and especially for women. We also find that subsidies already have the desired effect at 25% of total childcare costs and that the marginal utility of higher subsidy levels decreases beyond that threshold. Subsidies covering 25% of the total costs for childcare lead to an approximately 2 h per week increase in the labor supply of women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ever since the slow but steady erosion of the male-breadwinner model and the therewith associated gender stereotypes, childcare has been a more or less constant hot topic on the political table. From an economic point of view, childcare arrangements are especially pertinent in regard to their role in facilitating or hindering female labor supply. In this context, various policies aiming to raise the portion of mothers participating in the labor market have been developed and tried. Subsidizing day care centers is one such policy example that has been widely implemented. Although this policy has inspired an ever-growing body of research on both parental labor supply as well as child development and outcomes throughout the life course (e.g., Blau and Robins 1989; Blau and Tekin 2007; Connelly 1992; Heckman 2006; Herbst 2010; Vandell et al. 2010), some questions concerning their effects still remain. This is no wonder because examining the efficiency of subsidies in terms of the effects on job-take-up of parents with preschool-aged children and the number of hours they work is complicated by several factors. One of them being that labor supply decisions and the decision for or against the use of extrafamilial childcare solutions such as day care centers are interdependent (Davis et al. 2018). Parents of young children cannot consent to any employment situation without first assessing their options regarding childcare. Due to this interconnectedness, the underlying decision-making processes are in fact simultaneous. Because existing evidence is mostly based on observed choices, so far this simultaneity has only rarely been considered using experimental methods. However, gaining a better understanding of these decisions is not only interesting from a theoretical point of view but there is a practical value as well. In light of the obstacles families with preschool-aged children face when attempting to reconcile childcare and employment (e.g., Avellar and Smock 2003; Blau and Robins 1988; Havnes and Mogstad 2011; Kimmel 1998), in-depth knowledge is needed for the development of purposeful social policies aiming at a better compatibility of family and work in general. Especially for mothers of young children, there is a high potential for more labor market integration that targeted policies could help unfold.

In this paper, we focused on the simultaneous decision-making process parents undergo when organizing work and family life. Because in Switzerland day care centers are the primary source of extrafamilial childcare and subsidies are a fairly straightforward policy tool with a wide implementation, our study, set in the City of Bern, examined their effectiveness on labor market participation. Existing studies on the topic have mostly depended on survey or quasi-experimental data (from natural experiments on abrupt policy changes) and therefore offer only post hoc conclusions about the relevant decision-making process (e.g., Bauernschuster and Schlotter 2015; Kornstad and Thoresen 2006; Lefebvre et al. 2009; Lefebvre and Merrigan 2008). The experimental work that has been done so far on the other hand, has focused on providing subsidies to families that are usually not eligible for such policies (Michalopoulos 2010; Michalopoulos et al. 2010). Another strategy has been to exploit the introduction of vouchers for private day care centers to measure the impact on labor market participation (Viitanen 2011). Our goal was to complement these findings with a survey experiment. While some might argue, that the external validity can be disputed, and especially that, since they face no real-life consequences, caution is appropriate in regard to respondents’ statements (Collett and Childs 2011; Train 2009), survey experiments combine the strengths of experimental designs with those of large-scale surveys. On the one hand, the identification of causal effects is ensured through the random assignment of participants to different treatment combinations. On the other hand, as the data are collected in surveys with large and random samples, the method ensures the results have a higher external validity than traditional experiments conducted in the lab (Auspurg and Hinz 2015). Additionally, because several factors of interest can be manipulated in one survey experiment (multiple treatments), this approach yields detailed information on what drives parental decision making for the dual decision they are forced to make when taking up an employment and arranging childcare for their children.

Using a factorial survey experiment, we experimentally altered both labor market as well as childcare-relevant factors. We were thus able to account for the fact that deciding in favor of a job offer was contingent on childcare opportunities (Davis et al. 2018). By manipulating the costs associated with childcare (amount to pay, distance from home in minutes) as well as the expected benefits of taking up an employment (wage rate), we explicitly modeled people’s labor market behavior as a response to varying subsidies. Our main interest lay in assessing whether childcare subsidies had the intended effect of increasing the labor supply of families with small children in general and of mothers in particular. Furthermore, we were especially interested in whether responses to subsidies varied across social groups with regard to gender, socio-economic position, and migration background. We also examined whether the amount of additional sources of income (e.g., income provided by a working partner/spouse, public assistance, and transfers) had an effect on the joint decision for or against a particular job offer and a prespecified day care arrangement. To our knowledge, this study is the first to take the simultaneity of the decision-making process regarding childcare arrangements and the amount of supplied labor into account in an experimental setting.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: in the next section, we outline the theoretical framework, describe the context of the study, and summarize existing evidence on the impact of childcare subsidies on parental labor supply. In the third section, we present the (experimental) data and the methodological framework used to evaluate our model and proceed with a presentation of our findings and robustness checks in the fourth section. We conclude by critically discussing potential limitations and the implications for (future) policies.

Background

Theoretical Model

In order to understand the simultaneity of people’s decisions for a specific childcare arrangement and the hours they spend in the labor market, we relied on a standard labor supply model (Creedy and Kalb 2005). Labor supply decisions comprise the choice whether to take part in the labor market and, if yes, how many hours to work. The theory maintains that labor market participation and the number of hours people choose to work are the result of an evaluation of the expected monetary and non-monetary benefits and costs associated with a certain employment for one thing; and the time (and quality thereof) that remains for one’s children and family for another (Becker 1965, 1974, 1991; Connelly 1992). Likewise, the availability and quality of different care arrangements for one’s children further shapes the decision for or against an employment and the hours spent in paid employment.

Following the theory, people evaluate the utility of taking up an employment and of supplying a specific amount of labor based on an evaluation of consumed goods, the quality of childcare, and time remaining for leisure and to be spent with one’s children, respectively (Connelly 1992; Kornstad and Thoresen 2007). More specifically, excluding the possibility of a potential feedback effect of subsidies on people’s wage rates, we concentrated on the resulting monetary costs and benefits (Connelly 1992; Kornstad and Thoresen 2007; Viitanen 2005). Given that the revenues from employment must cover consumption and childcare expenditures, we expected subsidies to affect labor supply by reducing the costs of childcare. However, subsidies could have an effect in two opposing directions. On the one hand, people might reduce the number of hours they are willing to work since subsidies reduce the costs of childcare (income effect). However, this implies that consumption is fixed. Based on a rational action framework, the utility of a certain labor supply depends on the predicted net earnings after taking costs for childcare into account or, in other words, the money that can be used for consumption (Aaberge and Colombino 2014; Becker 1965; Herbst 2010). On the other hand, subsidies could encourage higher levels of labor supply by increasing the monetary payoff of working more hours and thus generating higher opportunity costs of working less hours (substitution effect). Under the assumption that time for leisure is a “normal good”, the relative strengths of income and substitution effects will determine the amount of supplied labor (Mincer 1962).

Based on these broad assumptions, people’s labor supply depends on the wages they receive from their jobs as well as on the amount of income from their paid labor and other sources, especially from other household members who are engaged in wage labor (Chiappori 1992; Haan and Wrohlich 2011; Powell 2002; Ribar 1995). Furthermore, as far as there are differences in people’s preferences for various commodities, their response to subsidies will likely also differ across social groups, such as by social status, migration background, and gender (e.g., Baker et al. 2008; Blau et al. 2006; Nollenberger and Rodríguez-Planas 2011). This expected heterogeneity is discussed further below. First, however, we outline the context of the present study and examine existing evidence on the effect of childcare subsidies in general.

Context

The present study was set in Bern, the capital city of Switzerland, and with 133,798 inhabitants (Federal Statistical Office 2019a) the fifth largest city. In Switzerland, children enter compulsory school at the age of six, after usually having attended kindergarten for 2 years (in some cantons kindergarten is not compulsory or only compulsory for 1 year, but even in these cases the vast majority of children attend kindergarten for 2 years). Day care centers always provide care for preschool-aged children, and sometimes accept kindergarten children as well. In Bern, about 85% of parents regularly resort to extrafamilial childcare and 62% of the children involved receive care in day care centers. Of those children, the vast majority spend either 2 (49%) or 3 days (28%) per week at the childcare center. Next to center-based care, care provided by relatives (e.g., grandparents) and friends is also of great importance (38% of all parents make use of such care arrangements), whereas only 3% of children in Bern experience care by a childminder or nanny (Ecoplan 2016). There is a high concentration of childcare centers in Bern and they are largely subsidized either directly with childcare slots at income-based prices or with childcare vouchers. On the whole, this makes Bern a context with readily available center-based care.

Concerning the labor market in Switzerland, the employment rate among permanent residents aged 15 years and older is 68%. Differentiated by gender, 74% of men are in paid employment while women’s employment rate amounts to 63% (Federal Statistical Office 2020b). However, on closer inspection it becomes apparent that Switzerland is still a male-breadwinner country (e.g., Wise and Zangger 2017): While 82% of the employed men work full-time, only 40% of the women hold full-time jobs (Federal Statistical Office, 2020a). Consequently, a majority of women hold part-time jobs. Although about four-fifths (79%) of mothers with a child of 15 years or younger living in the same household are employed, 81% of them work part-time. At the same time, having a child hardly leads to a reduction of working days for men, who predominantly work full time (in the Swiss context, full-time refers to working 38–42 h per week; Federal Statistical Office 2016). For most people, deciding in favor of a full-time employment means cutting down on family time on weekdays. Unsurprisingly, the most important reason for working part-time in Switzerland is childcare (Federal Statistical Office 2019b).

Review of Relevant Literature

Because subsidizing childcare results in reduced childcare costs and higher net wages of parents, we address both the childcare subsidy literature as well as studies dealing with the costs of formal childcare. Although most of the recent literature finds that decreased childcare costs and the presence of more subsidized slots have a positive effect on parental labor supply, the results are nevertheless somewhat mixed. Differences in data quality and methods are one potential explanation for this heterogeneity; differences in policy design, maternal labor force participation rates as well as gender-specific and family related social norm differences across countries are further reasons (Brewer et al. 2016; Cattan 2016). It is also important to keep in mind that there is a qualitative and not only a quantitative difference when it comes to participating in the labor market and the hours worked. Due to a substitution effect, childcare subsidies increase labor market participation rates of mothers because they raise net wages. However, for mothers already engaged in paid labor, subsidies do not necessarily lead to more hours worked because of an income effect, which might lead mothers to choose “leisure”, or time at home, over more work (e.g., Boeri and Ours 2008; Cattan 2016). Furthermore, the intended effects of subsidies can be offset by crowding-out effects, causing dead-weight costs (Cattan 2016). Crowding-out happens when a policy change just leads parents to substitute their informal childcare arrangements, typically provided by a relative, such as the grandmother, for formal paid childcare, without adjusting the number of hours they work (e.g., Asai et al. 2015; Blau et al. 2006; Brewer et al. 2016; Heckman 1974).

The Context in Which the Policy was Introduced

Research on the effects of childcare policies has yielded different findings depending on the context of the policy at stake. In their analysis using data from the US, Blau and Currie (2006) found higher maternal employment rates among subsidy recipients compared to non-recipients.Footnote 1 However, the average hours they engaged in paid labor was similar among both groups. This finding can partly be explained by a crowding-out effect (Blau and Currie 2006). Further evidence from the US confirms that maternal employment rates increase with lower childcare costs and higher childcare subsidies (Anderson and Levine 1999; Berger and Black 1992; Connelly and Kimmel 2003; Herbst 2010; Kimmel 1998; Leibowitz et al. 1992; Tekin 2004, 2007). It should be noted here, that with average net childcare costs of about 40% of net earnings, in international comparison, the US has one of the highest formal childcare costsFootnote 2 (Cascio et al. 2015). Another such high-cost context is the UK, with a market-oriented childcare provision setting, that, failing to meet the demands of parents, results in queues for childcare. Subsidized care is mostly reserved for families in need such as low-income families, those with a child with disabilities or single parents (Viitanen 2005). Under these conditions, using subsidy price simulations, Viitanen (2005) showed that the price of childcare had only small effects on labor market participation and the use of paid childcare. Even with a 50% subsidy, informal care was favored (Viitanen 2005), presumably because formal childcare remained unaffordable or unattractive for low-income families.

For Québec, Canada, a context with a high demand for formal childcare in which newly introduced subsidies lowered the costs of formal childcare substantially, evidence points to a positive effect on parental labor supply: treating the introduction of a new childcare policy as a natural experiment, several studies found positive short- as well as long-term effects of reduced childcare fees on maternal labor supply (Baker et al. 2008; Lefebvre and Merrigan 2008; Lefebvre et al. 2009). A similar approach followed by Viitanen (2011), who exploited the introduction of vouchers for private childcare in 33 municipalities in Finland, somewhat contrasts with the findings from the Canadian context. While the vouchers increased the use of private childcare (especially in areas with an excess demand for childcare), they had no effects on the use of public care and no effects on labor force participation. However, since Finland was already providing high-quality and low-cost public childcare prior to the change in policy, this might explain the lack of effects on labor market participation (Viitanen 2011). This is in line with a finding from Sweden, as another provider of readily available and affordable center-based childcare, where, using simulations, Lundin, Mörk, and Öckert (2008) found that setting a cap on the price of childcare would have no further effects on the already high female labor market participation. For Norway, with a similarly well-developed affordable childcare system, Kornstad and Thoresen (2006) estimated that for a scenario that does not quite cover the demand for formal child care, maternal labor supply would increase by about 2 h per week. They estimated a larger increase of about 3.5 h per week for an alternate scenario with no queues for center-based childcare (Kornstad and Thoresen 2006). To the contrary, also for Norway, Havnes and Mogstad (2011) found no effects of expanding the subsidized childcare system further on maternal labor supply. Using difference-in-differences estimates, they found that the new policy, an expansion of subsidized formal childcare, only crowded out existing forms of informal care arrangements. On the other hand, Hardoy and Schøne (2015), also Norway, found a positive effect of reduced childcare costs. However, because the reform in question was accompanied by an increased supply of day care slots, the finding might have been induced by the latter circumstance or a combination of both factors (Hardoy and Schøne 2015).

On the other hand, countries with a less well-developed formal childcare system (smaller capacity and less government funding), exhibit a high potential for raising maternal labor supply with reforms. The evidence for the Netherlands (Graafland 2000), the UK (Viitanen 2005), Austria (Mahringer and Zulehner 2015), Spain (Nollenberger and Rodríguez-Planas 2011), and Russia (Lokshin 2004) suggests, that higher subsidies and lower childcare costs are important determinants of the maternal employment rates as well as hours worked. For Southern Italy, Del Boca and Vuri (2007) also found that both childcare availability and price of childcare were important determinants of maternal labor market participation. Price was especially important for mothers in areas with a higher availability of childcare slots (Del Boca and Vuri 2007). For Australia, Guest and Parr (2013) also found a significant positive effect of family benefits and childcare subsidies on the hours couples work. For Germany, subsidized childcare was estimated to have only a small effect on maternal employment decisions compared to other countries such as the US, Canada, or the UK (Haan and Wrohlich 2011; Wrohlich 2004). However, the authors claimed that the reforms would especially affect the subgroup of highly educated women as well as those having their first child, raising their labor supply as well as fertility rates.

Heterogeneous Responses to Subsidies

Apart from the broader policy context, various groups of people might also differ in their response to childcare subsidies, be it due to individual differences in resources or beliefs about childrearing. Because men still have a higher employment rate than women in Switzerland and men still mainly work full-time (e.g., Wise and Zangger 2017), there is a difference in the potential that policies can be expected to unleash. While men hardly have leeway to work more hours, women have more room to react. Due to this ceiling effect for men, it can be assumed that women react stronger to subsidies than their male counterparts. Nevertheless, the hypothetical nature of the factorial survey experiment also allowed us to investigate men’s preferences when childcare is subsidized. Furthermore, it has repeatedly been shown for mothers that those with a higher educational degree have a higher probability of being employed and of working more hours than those with lower educational degrees (Andrén 2003; Chiuri 2000; e.g. Connelly 1992; Del Boca and Vuri 2007; Guest and Parr 2013). This raises the question of whether parents respond differently to subsidies depending on their socio-economic status.

Existing research on the variation in parental responsiveness to different subsidy levels and childcare costs by social status (e.g., education, household income) has yielded mixed results. Regarding the educational background of parents, evidence is available for the US, Canada, Germany, and Spain. While in the US and in Spain those who were the least skilled were more affected by childcare costs (Anderson and Levine 1999; Haan and Wrohlich 2011; Nollenberger and Rodríguez-Planas 2011), in Canada, the effects did not vary by educational background (Lefebvre and Merrigan 2008), and in Germany, the responsiveness was highest for highly educated women (Haan and Wrohlich 2011). For the US, Herbst (2010) also found heterogeneous effects of childcare subsidies and effects of Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), but contrary to the German case, they primarily raised the labor supply for subgroups of single mothers, with low-income mothers responding most to EITC. Although Michalopoulos (2010) and Michalopoulos, Lundquist, and Castells (2010) found no overall effect of childcare subsidies on parental labor force participation, they also highlighted that the high-income families that predominantly constituted their sample had little room to increase their labor supply since they were already steadily and in high employment prior to the program.

Finally, evidence suggests that the migration background or ethnic descendance of parents also seems to affect labor market and childcare decisions. In the American context, Michalopoulos and Robins (2000), for example, showed that Black American mothers were more likely, while Hispanic/Latin Americans were less likely to work full time than White Americans. For the UK, results indicated a higher employment probability for White mothers compared to non-Whites (Viitanen 2005). However, to our knowledge, previous studies have not investigated whether or not the reactions to childcare costs and subsidies vary with ethnic or migration background. Nevertheless, given the position of migrants in the host country, potentially different values regarding childrearing, and differences in terms of resources and networks (e.g., absence of relatives who could provide informal care), they are nevertheless expected to vary in their response to subsidies.

What We Expect

Generally speaking, the evidence strongly suggests that the context in which subsidies are introduced greatly determines the effects the policy will have. In countries with a well-developed formal childcare system and high maternal labor supply, subsidies will only provoke small increases in maternal labor market participation and hours worked. Subsidies seem to have the highest impact in situations in which there is a higher availability of slots since costs are a factor parents can only seriously consider if they have a choice. In the present context of the City of Bern, Switzerland, there was a policy-related increase in the availability of day care centers shortly before this study was conducted and availability was no longer a major issue.

Because childcare slots were widely available in the present context, we expected positive effects of childcare subsidies on (maternal) labor market participation and labor supply (Hypothesis 1). However, subsidies have been shown to be particularly effective in raising the labor supply of parents in contexts with comparatively low employment rates and lower levels of formal childcare use, and especially when there is minimal crowd-out (Brewer et al. 2016). Since men and women’s employment rates differ considerably in the Swiss context, with men predominantly working full time (Wise and Zangger 2017), we further expected women to adjust their working hours more strongly in response to the amount of childcare subsidies than men (Hypothesis 2). With regard to heterogeneous responses due to varying resources, the expectation was less clear. On the one hand, mothers, for example, with more available non-labor income have a higher reservation wage. Consequently, we would expect them to exhibit higher levels of non-employment, even in the presence of higher subsidies (Cleveland et al. 1996; Viitanen 2005). On the other hand, women with the highest educational backgrounds can also expect the highest returns to labor, meaning they have higher opportunity costs of non-employment. However, this is why these women have higher levels of labor market participation and attachment in the first place and are not as dependent on childcare subsidies (e.g., Cattan 2016; Nollenberger and Rodríguez-Planas 2011). For this reason we expected parents with a lower social status and with less financial means from other sources to be more sensitive to subsidies, because for them working more would increases their household income significantly once childcare was subsidized (Hypothesis 3).

Finally, due to the near inevitable loss of social capital and the geographical distance to potential caregivers (e.g., grandparents), an overall higher reliance on formal childcare was expected for parents with a migration background. At the same time, many immigrants might also perceive a stronger economic necessity to work more due to a lower endowment with resources in the host country. It can thus be expected that those who were born abroad were somewhat more likely to start employment and to increase their labor supply with increasing subsidies (Hypothesis 4). Summing up, we expected the probability of parents’ choosing to go to work and of using center-based care to rise with subsidy levels. In the context of Bern, with relatively widely available good-quality care, we expected only moderate effects. In regard to the number of working hours, we expected the effects to differ with socio-economic status and financial resources, migration background, and gender. We expected people with lower social status and available income from other sources, people with a migration background and women to react stronger to subsidies.

Data and Methods

Data

To investigate to what extent and for whom childcare subsidies made a difference, we drew on data from a research project on the use of childcare services conducted in the City of Bern, Switzerland. A factorial survey experiment was included in both the paper pencil as well as online version of a questionnaire that was distributed to parents with preschool-aged children in a day care center is the basis for our data analysis. The data were collected in 2015 and the sample stems from 25 day care centers which were selected at random (out of approximately 70) in Bern. The share of children in the neighborhoods served as a stratifying variable. In order to guarantee a completely anonymous data collection, all households with children in one of the selected day care centers were invited to participate. A total of 540 respondents returned questionnaires either per mail or online, reflecting a response rate of roughly 60%. While our sample was already a selective subpopulation of parents with small children (only those who resorted to formal care in a childcare center), respondents in our sample might further differ from nonrespondents. Although our sample matched the population quite well with regard to observed characteristics such as education or migration background (with approximately two thirds holding a tertiary degree; Ecoplan 2016), those who did not participate might have differed on unobserved attitudes and values regarding, for example, childrearing or the value attached to care in childcare centers.

In the factorial survey, respondents were confronted with a hypothetical situation in which they were asked how likely it would be for them to accept a described job offer and how many working hours per week they would ideally opt for. The job was described as suited to the respondents’ skills and qualifications and they were also told that if they accepted the job offer, there would be an available center-based childcare arrangement that met their expectations. The parts of the job description that were experimentally varied were: the income the job would provide (amounting to either 190, 270, or 350 Swiss Francs per dayFootnote 3), the income available from other sources (e.g., from a working partner/spouse earning 3,200 vs. 4,900 vs. 7,800 Swiss Francs per month), the price of the day care arrangement after taking subsidies into accountFootnote 4 (25, 50, or 90 Swiss Francs per day), and the time it takes to get to the place of the day care arrangement (5, 15, or 25 min). Since center-based care was strongly regulated in Bern, the total costs (without subsidies) were roughly the same across all providers and amount to 120 Swiss Francs per day (Ecoplan 2016). As a consequence, subsidies entered into the analysis as the difference between the hypothetical amount to pay and the full costs of 120 Swiss Francs per day. Additionally, we experimentally altered the number (one or two) as well as the age of the children (6 months, 18 months, or 3 years) needing day care. The setup of the fractional factorial was D-efficient, with an efficiency of 96.36 (Auspurg and Hinz 2015). The summary statistics of the characteristics included in the factorial survey experiment as well as the other covariates are shown in Table 1. The first column summarizes the descriptive statistics based on a listwise deletion of cases with missing values; the second column depicts the corresponding values when missing values are multiply imputed (MI). A sample vignette is shown in Fig. 4 of the “Appendix”.

Although the dependent variable was measured on a metric scale from 0 to 100, reflecting the desired working days in full time equivalent (FTE), it was nevertheless recoded into distinct working time categories. Because people normally chose to work a number of whole days and not a continuous number of hours, this procedure seemed most appropriate for the research question at hand. Furthermore, this approach was also in line with the theoretical background presented in Background section and allowed for an alternative-specific influence of the costs and benefits of participating in paid labor (Aaberge and Colombino 2014; Creedy and Kalb 2005). For this reason, the originally metric variable measuring parents’ labor supply in the factorial survey was recoded into six categories, reflecting whether parents chose to work anywhere between one to five working days per week or not to work at all. Since only 11 people chose to work on 1 day per week, this category was merged with the next higher one so that the resulting dependent variable had five categories. Given this setup, the hypothetical earnings and the amount of subsidies entered as alternative-specific variables into the model, that is, they varied with the amount people chose to work and thus no longer reflected daily but weekly earnings and subsidies. Likewise, we entered the amount of leisure, defined as the difference between 80 h. (\(5\times 16 \mathrm{h})\) and the chosen amount of work as an additional alternative-specific variable (Creedy and Kalb 2005).

Apart from the effects of the dimensions specified in the factorial survey, we were mainly interested in differential responses to subsidies by social and migration background as well as by gender. The social status of the respondents was determined according to the International Socio-Economic Index (ISEI) of their current or last occupation. Although analyses with the highest level of education yielded comparable results, it can be argued that, compared to the accumulated human capital in form of educational credentials, an occupation-based measure more accurately reflected people’s standing in society (Bukodi and Goldthorpe 2013). Regarding migration background, we relied on a dichotomous indicator of whether a respondent was born in Switzerland or not. While a more detailed operationalization was possible (e.g., in terms of grouping countries of origin), doing so resulted in very small cell sizes which were problematic for both the multivariate models and the subsequent simulation analyses. Finally, next to the gender-specific influences that we accounted for in separate models for women,Footnote 5 we also controled for a set of other observed characteristics. These included whether the respondents were a single mother or father, their labor supply in real life, their age, and satisfaction with their work–life balance. This last item as well as the observed labor supply in the real world were included as crude proxies for unobserved preferences that work otherwise than through the cost and benefit considerations parents make when deciding on their labor supply and childcare arrangements. Because part-time employment is common in Switzerland (Wise and Zangger 2017), people’s actual labor supply and their satisfaction with their work–life balance captures additional aspects of the trade-offs (e.g., in regard to leisure or spending time with one’s children) and preferences for supplying a particular amount of labor.

Given the rather small sample size and in order to obtain robust estimates, the data were multiply imputed using chained equations (Allison 2001; White et al. 2011). To this end, 200 imputed datasets were generated. Due to the experimental setup, missing values were only generated for the respondent characteristics (with a maximum of 7.0% missing values for respondents’ ISEI) and on the dependent variable (12 cases or 2.2% missing values). However, because the results of the multivariate models did not differ when deleting all observations with missing values (listwise deletion) on one or several characteristics and since the simulations require non-imputed data, we presented estimates based on a listwise deletion of observations with missing values. The corresponding estimates based on the multiply imputed data are presented in Table 4 of the “Appendix”.

Methods

Based on the theoretical framework, people choose a specific number of working hours based on the costs and benefits associated with each of the different working time categories. By design, this is equivalent to the hours their children will spend in extrafamilial care, which is why we modeled labor supply as a function of characteristics on both the individual as well as the vignette level. The obvious model of choice is the well-known McFadden’s (1974) alternative-specific conditional logit model.Footnote 6 Thus, an individual \(i\)’s probability of choosing the \(j\)th working time category writes as

where \({\varvec{X}}\) is an \(n\times m\) matrix of alternative-specific characteristics (in the present context \(i\)’s earnings as well as the subsidies for center-based childcare and the amount of leisure associated with each of the working time categories) and \({\varvec{Z}}\) is an \(n\times p\) matrix of individual characteristics (e.g., respondents’ ISEI, but also the time needed to get to the childcare center in the factorial survey). Indicated by the index \(j\), the influence of respondents’ characteristics are allowed to differ across alternatives. It should further be noted that due to the design of the factorial survey, the additional household income from other sources is considered to be fixed—a condition that might not always be met in real life (e.g., Moffitt 1984; Powell 2002).

As we used data from an experimental setting, we estimated the utility function \({\widehat{U}}_{ij}={{\varvec{x}}}_{ij}^{T}\widehat{{\varvec{\upbeta}}}+{{\varvec{z}}}_{i}^{T}{\widehat{{\varvec{\upgamma}}}}_{j}\) for each individual to examine the effect of varying levels of subsidies in detail. We predicted the probability \({\widehat{\pi }}_{ij}\) of choosing each working time category \(j=\{1,\dots , 5\}\) after altering the amount of subsidies for each individual \(i\). The simulated amount of subsidies covered either 25%, 50%, 75%, or 100% of the costs of childcare in a day care center.Footnote 7 Based on these predicted probabilities, we identified parental labor supply in comparison to a counterfactual scenario with no subsidies. In a first step, we examined the extent to which subsidies served as a stimulus to pick up an employment. In a second step, we investigated whether and to what extent subsidies increased the amount of working hours for those who chose to work even if childcare was not subsidized at all. The difference in the supplied hours of work with and without subsidies was then averaged over all observations and for different subgroups, defined by gender, socio-economic status (ISEI), migration background, and the hypothetical income from other sources. Standard errors for these predictions were obtained using the bootstrap method (Efron and Tibshirani 1986), with 200 iterations per simulation.

Finally, we checked the sensitivity of the methodological approach. First, we used weights to test for potential erroneous conclusions due to a selective nonresponse. There was no marginal distribution available for the specific reference population of the data (parents with preschool children in the City of Bern with at least one child in a day care center). However, using pooled data of the Swiss Structural Survey that replaced the census as of 2010 (Federal Statistical Office 2017), it was possible to get approximate marginal distributions for some demographic characteristics for all families with children aged zero to six in the City of Bern. Using these distributions for respondent’s education and migration background, raking was used to obtain weights for the multivariate models. Although the results did not differ much (see Table 5 in the “Appendix”), the use of these weights affected the precision of the estimates, increasing the standard errors of some characteristics (e.g., earnings, subsidies) and decreasing them in other cases (e.g., migration background). More importantly, the marginals used did not directly correspond to the population of interest since, as outlined above, only 62% of these families resorted to center-based care. Since there was no data available for the exact reference population, we did not use any weights in the following descriptive and multivariate analyses. Nevertheless, the weighted analyses served as additional robustness checks which are discussed at the end of the “Results” section.

Additionally to weighting, we used the procedure described in Barslund et al. (2007) to assess whether personal beliefs and values about childrearing and childcare affected the estimated economic measures (subsidies, earnings, leisure). We included information on whether respondents used informal childcare, whether center-based care was their only option, and whether they held conservative family values (using the importance attached to their child having a family of their own one day as a proxy). As a second robustness check, we tested whether adding this information changed the magnitude and significance of the effects of interest. In a third step, we also investigated whether using the original metric outcome measuring people’s supplied labor in fulltime equivalent percentages (0–100%) led to comparable results.

Results

Working Days in the Survey Experiment and in Real Life

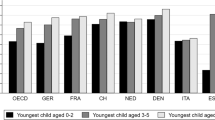

Before we turned our attention to the multivariate analyses and simulation results, we briefly compared how many working days per week the respondents chose in the factorial survey compared to their real-world labor supply. We also described how these figures compared across groups. Figure 1 shows a large overlap between the respondents’ hypothetical labor supply in the factorial survey and their labor supply in the real world. Against the background of a flexible labor market and the widespread possibility of working part-time in Switzerland (Gerfin and Lechner 2002), this finding suggesteds that many of the surveyed parents worked the desired number of hours. However, we also observed that a considerable share of respondents, and especially men, chose to work less in the factorial survey than they actually worked in real life. While most male respondents worked full-time (4 or 5 days), female respondents predominantly worked only part-time (Fig. 1a). This is in line with previous findings, characterizing Switzerland as a male-breadwinner country (Wise and Zangger 2017). We used this close correlation between the observed and the hypothetical labor supply in the factorial survey to take some unobserved heterogeneous preferences into account in the following model estimation.

Comparing the labor supply in the survey experiment and the real world across different status groups, it appeared that especially high-status respondents chose to work less in the hypothetical situation (Fig. 1b). This also held true for parents who were born in Switzerland (Fig. 1c). These different patterns for men and women, status groups, and for people born in Switzerland as opposed to those born abroad indicated heterogeneous labor supply preferences and possible varying responses to the experimentally altered amount of subsidies in the factorial survey.

Determinants of Parental Labor Supply

Having seen that people made heterogeneous labor supply decisions depending on their gender, social status and migration background, we then examined to what extent parents reacted to subsidies. Table 2 summarizes the results of the alternative-specific conditional logit analysis based on data using listwise deletion of missing values (see Table 4 in the “Appendix” for the same results with multiply imputed missing data). The effects are reported as the log odds in favor of choosing one of the working time categories in the factorial survey as opposed to not taking up the job.

When it came to the experimentally varied treatments, we saw that parents opted to work more hours, the more they could earn working and the higher the subsidies (equivalent to lower childcare costs). For a unit increase in subsidies, the odds of choosing a particular working time category increased by \({e}^{0.005}=0.5\%\). A corresponding unit increase in daily earnings for a working time category increased the odds of choosing this particular alternative by \({e}^{0.004}=0.4\%\). This is in line with our theoretical considerations. Moreover, we included the time for leisure as an additional alternative-specific variable. This is not only a standard approach in labor supply modeling (Creedy and Kalb 2005) but it also enabled us to account for the trade-offs people were forced to make when choosing how many hours they wanted to work, most importantly between income and free-time. One hour more of free time increased the odds of choosing a specific working time category by \({e}^{0.389}=47.5\%\). This clearly demonstrated the trade-offs between working more and having more money (substitution effect) due to subsidized childcare on the one hand and the value of leisure on the other (income effect). Also, as expected and in line with existing research (e.g., Hardoy and Schøne 2015; Powell 2002), the higher the household income from other sources, the less parents tended to choose to work only up to 3 days as opposed to not working at all (significant on the 10% level). This was especially true for mothers who were significantly less likely to opt to work full time (the odds decreased by about \(1- {e}^{-1.388}=75.0\%\)), the higher the household income from other sources. Since the childcare arrangement in the factorial survey was described as matching the respondents’ needs, it was perhaps not too surprising that the experimentally altered distance to the childcare center had no additional effect. Compared to those with one child, parents described having two children in the factorial survey had a somewhat increased likelihood of deciding not to work at all or only up to 3 days per week. However, this was only marginally significant in the combined model for men and women. Furthermore, for women, the age of the youngest child in the factorial survey seemed to have a minor influence. The older the youngest child, the higher the probability that they chose to work only up to 2 days as opposed to not at all.

When looking at the respondent variables, we saw that there was no significant gender effect. However, this might have merely reflected the fact that the significantly higher share of women in the sample drove the results. Similarly, the family situation—whether the respondent was a single parent or not—had no effects either (controlled in all models but not reported). The ISEI of a respondent, on the other hand, influenced their work and childcare related choice. The higher the ISEI of a respondent, the less likely they were to choose to work 5 days a week: a unit increase in social status decreased the odds of choosing to work full time by about \(1-{e}^{-0.063}=6.1\%\). Given that a higher socio-economic status is commonly also associated with a higher income, this negative effect might have reflected a decreasing marginal utility of working additional hours for highly skilled and highly paid parents who also valued spending time with their children. Finally, respondents who were not born in Switzerland seemed more likely to choose to work on 4 days or full-time: the odds of working 4 or 5 days a week were 87.9% and 98.0% lower for people born in Switzerland than for those born abroad. For the subsample of women, this effect was less pronounced and was only marginally significant (10% level) for the 4 days option.

As a means of testing for possible heterogeneous responses to subsidies, we included interaction terms for subsidies and parental background characteristics (ISEI, migration background). However, none of these interactions had a significant effect. Similarly, the interaction of the amount of subsidies with the income from other sources in the factorial survey was also not significant. We therefore excluded the interaction terms from the models in Table 2. On first sight, we would conclude that subsidies seemed to increase the labor supply of parents, both men and women, and that this effect was the same across different social groups.

Extent of Labor Supply Increase Due to Subsidies

Up to now, the results indicated that subsidies did indeed affect parental labor supply decisions but gave no indication of group-specific responses to subsidies. Also, the reported log odds in Table 2 told us little about the extent to which subsidies made a difference. Moreover, subsidies might have merely served as an incentive to get employed but they might not have greatly affected the hours worked. Subsidies might, for example, lead to crowd-out effects or the income effect might outweigh the substitution effect, leading parents to work less and enjoy more leisure (Blau and Currie 2006). To differentiate the effect of subsidies on the hours supplied from their effect on taking up an employment, Fig. 2 shows the effect of subsidies for those (in the setting of the factorial survey experiment) who would not work at all if there were no subsidies available. Based on the models in Table 2, only about 6% of all respondents were predicted to choose not to work at all (dotted reference line). Once subsidies cover 25% of the costs for center-based care, this share dropped to only about 2%. The corresponding confidence intervals were obtained by means of 200 bootstrap iterations. Holding all other model covariates constant, additional subsidies covering 50%, 75%, and even 100% of the price of the day care center further lowered the share of people who would not work to 0%. Likewise, the confidence intervals become smaller, indicating less heterogeneous responses despite the fact that subsidies covering the entire costs were out of sample predictions.

Figure 2 suggests that childcare subsidies had a considerable impact on peoples’ decisions regarding job take-up. Even modest subsidies covering 25% of the costs already caused almost everybody in our sample to take up a job. However, since the share of people in our sample who would not work in the case of no subsidies was small, differentiated analyses including individual background characteristics were not possible.

Figure 3 depicts the effect of childcare subsidies on the supplied labor for those who would even work in the case of no subsidies. To test for heterogeneous responses, the results are presented for different subgroups. A first inspection of the three charts in Fig. 3 suggested that subsidies do increase parental labor supply (Hypothesis 1). For those who would work in any case, subsidies covering 25% of the costs for childcare increased their labor supply by, on average, about 2 h per week (this is about a quarter day’s work by Swiss standards). However, the results suggested that the marginal utility of the amount of subsidies decreases quite rapidly. When subsidies cover 50%, 75%, or 100% of the costs, the additional increases in labor supply were relatively small in comparison. In addition, with increasing subsidies, the standard errors of the estimated change also increased (also obtained through 200 bootstrap iterations). This could have been a reflection of the expected ambiguity outlined in the “Theoretical Model” section: higher subsidies not only increased the monetary payoff associated with working more hours (substitution effect) but they also enabled parents to maintain their levels of consumption with fewer hours of paid work and thus allowed them to spend more time with their children (income effect).

Turning our attention to the variability in responses across the mentioned respondent characteristics, we first noted a considerable difference between men and women (Fig. 3a). When subsidies cover 25% of costs, women increased their labor supply by almost two hours per week on average. Meanwhile, the only effect that can be observed for men was for those from the lowest quartile of the status distribution and for the case in which subsidies covered at least half the costs. More generally, although at most marginally significant, men seemed to react only to higher subsidies: if they covered `only’ 25%, they hardly reacted at all. While this finding was consistent with our expectations (Hypothesis 2), the nonsignificant results for men might have merely reflected the small sample size.

Regarding social status, we saw the expected decline in people’s responsiveness to childcare subsidies as their status increased (Hypothesis 3). While this trend was almost linear for women and people born in Switzerland, the pattern was somewhat more heterogeneous for men and those born abroad. The effects for these latter two groups were only rarely significant and might—as outlined above—also have reflected the small sample sizes. Moreover, while parents born in Switzerland generally increased their labor supply by about 2 to 4 h per week, the effects for those born abroad were almost never significant at the 95% confidence level (Fig. 3b). However, it seemed that people born abroad were somewhat more responsive to higher subsidies, which would be in line with our expectations in Hypothesis 4. The mostly nonsignificant results for those born abroad might again have resulted from the small sample size of people with a migration background.

While the results of the simulation have been in favor of an interpretation suggesting that people who are financially less well-off in real life (lower social status, people with a migration background, and women) can be induced to work more by childcare subsidies, the last chart in Fig. 3 shows a somewhat contrary picture. When looking at the household income from other sources, which was also experimentally varied in the factorial survey, we saw that those with more financial resources were somewhat more likely to increase their labor supply. Again, this finding is reported here only for those who chose to work irrespective of the availability of childcare subsidies. Since those with higher monetary resources generally did not perceive the ‘necessity’ to work more (Table 2), they also had more room left to increase their labor supply once subsidy levels increased. Those who were confronted with less monetary resources in the experimental setup, however, were already more likely to work more hours to begin with, irrespective of the amount of available subsidies.

Robustness of the Results

Although respondents were asked to abstract from their own situation and the covariates of interest were experimentally altered, it is nevertheless possible that our results were driven by omitted variable bias and the selective nature of our sample (due to nonresponse and the sampling itself). This is why we ran several robustness checks.

Firstly, to address the potential nonresponse bias, we re-estimated the models in Table 2 by means of multiply imputing missing values using chained equations (generating 200 imputed data sets). Table 4 in the “Appendix” depicts the results, indicating that at least item-nonresponse did not seem to be a big issue in the present case (which was not surprising given that, due to experimental setup, only few variables had missing values; see above). Additionally, we addressed the potentially selective unit-nonresponse by means of weighting the data as an additional test. As outlined above, there were no exact population level marginals available for the reference population of our sample, consisting of parents with children who are 6 years old or younger and who are looked after in a childcare center in the City of Bern, Switzerland. This is why we used pooled data from the structural survey as an approximation. We then raked the data on respondents’ education and migration background to construct weights. The results are shown in Table 5 in the “Appendix”. Again, there was no real difference in the main effects of interest, which are also shown in the first column of Table 3.

Although omitted variable bias is less of a problem when data from traditional experiments are used (Angrist and Pischke 2009), there might still be unobserved variables that affect respondents outcome measures in factorial surveys and which, at the same time, lead them to evaluate the experimentally altered dimensions differently. In the present context, especially values and experienced but unobserved constraints might vary greatly among respondents. We tested whether including information about people who used additional informal childcare (crowding out effects), those who only used care in childcare center due to a lack of other care alternatives, and a proxy for conservative family values (whether they would like their child to have a family of their own) changed the documented effect of childcare subsidies.

For this sensitivity analysis aiming to test whether the omission of the above measures led to biased results, we drew on the method used by Barslund et al. (2007). This allowed us to assess the degree to which including these measures would alter our estimates of interest. Table 3 presents the results of this exercise. The inclusion of any of the three additional measures did not change the coefficient of either the subsidies, the gross income, or of leisure in a meaningful way. Moreover, the additional analyses, yielding highly significant results in all the models, also highlighted the stability of the effects across different models.

Finally, to test the dependence of the results on the chosen methodological approach, we also ran analyses with the original, metric outcome measure (Fig. 4 in the “Appendix”). Using linear models yielded the same interpretation of a significant, positive effect of the amount of subsidies on parental labor supply (Table 6 in the “Appendix”). Considering the robustness of our findings throughout these different approaches, we are confident that subsidies do indeed have the effect outlined in the simulations above: they generally increase labor force participation, and they tend to increase the number of working hours of people in the lower quarter of the status distribution, women, and those who have no migration background—at least against the backdrop of a setting in which center-based childcare is widely available and used.

Discussion

Politically speaking, childcare subsidies can be understood as a social investment aiming to help families with preschool-aged children to reconcile their work and family lives by offering parents an incentive to go (back) to work. Encouraging parents to make use of high-quality childcare arrangements can also more generally increase the life chances of children from less privileged backgrounds throughout the life course (Heckman 2006). In this paper, we evaluate whether subsidies achieve their goal of raising the labor supply of parents in general, and mothers in particular, using a factorial survey experiment. To do justice to the simultaneous nature of the decision to take up a job and find a childcare arrangement, we used a factorial survey experiment in which characteristics of the prospective job (gross earnings) as well as aspects of the childcare setting (e.g., subsidy level, distance to the childcare center) were experimentally altered. Moreover, to take the joint decision making of partners/spouses into account, the income from other sources (e.g., from a working partner/spouse) was also provided (Creedy and Kalb 2005; Moffitt 1984). The respondents were asked to decide whether or not they would agree to take up a described job. If the parents agreed to the job offer, they were additionally asked on how many days they would choose to work and place their child or children in the portrayed day care center.

Relying on standard labor supply model (Creedy and Kalb 2005), we argued that the supplied working hours are the result of an evaluation of both the expected monetary as well as the non-monetary costs and benefits associated with taking up a certain job and the time that remains for leisure or family life (Becker 1965, 1974, 1991; Connelly 1992). Since higher subsidies also increase the opportunity costs of the hours not spent working (substitution effect), we expected higher levels of childcare subsidies to increase labor supply. On the other hand, in a context like Bern, according to previous research results (e.g., Hardoy and Schøne 2015; Herbst 2010; Michalopoulos et al. 2010; Viitanen 2011), we expected these positive effects to be rather small. We also hypothesized that lower status parents as well as parents with less available income from other sources would respond more strongly to subsidies, since the costs of childcare have a greater impact on their household budgets. Furthermore, we expected that people born abroad might more strongly react to subsidies since they lack alternative resources for childcare (e.g., care by grandparents might not be available) and that they perceive a greater economic pressure for working more. Finally, we anticipated that due to the fact that a majority of fathers hold full-time jobs, subsidizing childcare would primarily affect mothers because they predominantly work part-time and thus have leeway to increase their labor supply (Wise and Zangger 2017).

Using an alternative-specific conditional logit model to analyze the experimental data, we examine whether subsidies affect parental labor supply. We find that subsidies do make a difference and contribute significantly to increasing both labor market participation of parents as well as the number of hours they work. Using simulations based on the estimated utility function, subsidies seem to be especially suitable as an incentive to take up a job in the first place. Moreover, we see that subsidies have somewhat differing effects on the willingness to work additional hours across gender, social status, and migration background. While subsidies have nearly no effect on men, they increase the labor supply of women by approximately 2 h per week if they cover 25% of the total costs for childcare. When subsidies cover even larger shares of childcare costs, their marginal utility falls quite sharply. Moreover, parents and especially women of a lower social status show the highest responsiveness when it comes to increasing their labor supply due to subsidies (up to 4 h per week). Men and people born abroad, on the other hand, seem to increase their labor supply only when subsidies cover significantly higher shares of the childcare costs. Contrary to this picture, we find women react slightly more strongly to subsidies when they are confronted with a higher income from other sources in the context of the factorial survey. This, however, might merely reflect the fact that they were less likely to work (almost) full-time and thus have, on average, more leeway to increase their labor supply than those who are confronted with less resources in the experimental design and thus opted to work more to begin with.

Thus, while the documented modest increases in parental labor supply are mostly in line with findings in the literature (e.g., Hardoy and Schøne 2015; Herbst 2010), the differentiated analyses also highlight the importance of considering heterogeneous responses to childcare subsidies. In this regard, subsidizing childcare especially boosts the labor supply of women and parents of a lower social status. While this is in line of articulated policy goals, a more thorough examination of this result is a task for future research. Given the small sample sizes for men and people with a migration background in the present study, it remains an open question if they truly only react to more substantial increases in available subsidies as reported in our findings or whether this is caused by—at least for men—a ceiling effect.

Limitations

Several limitations have to be kept in mind when reflecting upon the results of this study. Firstly, the findings apply to a specific (sub-)national context with a high labor market participation, widely available part-time jobs, and where childcare centers are commonly used and available to parents. At the same time, a male-breadwinner model is still the dominant ideology in Switzerland (Wise and Zangger 2017). Thus, the results cannot be generalized to other national contexts and instead constitute an addition to the heterogeneous findings in the international context (e.g., Havnes and Mogstad 2011; Lefebvre et al. 2009; Lundin et al. 2008; Tekin 2007).

Second, although based on a random sample and using experimental techniques, the findings might nevertheless be driven by the specific sample composition. All parents in the sample already use formal childcare. Thus, they may be more responsive to childcare subsidies than the more general population of parents with preschool-aged children. Moreover, the sample consists of respondents living in an urban area in which formal childcare is used by a majority of parents and might thus not apply to more rural contexts. We ran several sensitivity analyses to assess the extent to which this selectivity could have affected our estimates. Applying two approaches—first using weights and second by assessing the sensitivity of the results to the omission of variables concerned with values and attitudes regarding childcare—we find a coherent, positive effect of subsidies on the amount of supplied labor. However, although the experimentally altered dimensions in the factorial survey have a high explanatory power, indicating that people did indeed abstract from their real-world situation, we cannot be completely sure of the validity of the survey experiment (Collett and Childs 2011). It remains an open question whether those who have not yet used formal childcare institutions would respond in the same way. This last point is not only of interest for future research but is also vital for the future development of efficient reforms. We need more research on the subject and especially such that targets parents who are skeptical of center-based childcare and hard-to-reach populations.

However, keeping the limitations in mind, our results speak in favor of subsidies as an effective policy measure to raise the labor supply of parents with young children. While subsidies increase parental labor supply in general, those with commonly less resources (women and those of a lower social status) are especially responsive. Also, it appears that lower subsidy levels already have the desired effect. A more detailed analyses of optimal subsidy levels for different subpopulations would undoubtedly be of great value for the development of future policy.

Notes

As the authors acknowledge, this is partly due to the fact that some of the examined subsidy programs required the parents to be employed or in education.

The OECD average net costs of childcare are around 17%, with a high range (Cascio et al., 2015).

One Swiss Franc roughly correspondents to one US dollar.

We opted for this measurement; full price minus the subsidies, since it is most in line with the concept of costs according to economic theory (Herbst, 2010).

Because of the lower number of cases for men (190 or 35% of all cases), separate models were only possible for women.

Alternatively, one could argue that the decision on how many days one would like to work on, is preceded by the decision whether or not to work at all. This would suggest a hierarchical decision structure in which the odds for choosing one particular working time category depend on the presence or absence of other alternatives. This would violate the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) criterion of the conditional logit model (Cameron & Trivedi, 2009). A nested logit model could be considered instead. However, given the hypothetical nature of the choice experiment in which people could freely choose the number of hours they wanted to work, the IIA can be assumed not to be violated in the present case.

In the vignettes, subsidies covered, on average, 55.97% of the costs of care in a childcare center. The share of costs covered by subsidies ranged from 25.00 to 79.17%.

References

Aaberge, R., & Colombino, U. (2014). Labour supply models. In C. O’Donoghue (Ed.), Handbook of microsimulation modelling (pp. 167–221). Emerald.

Allison, P. D. (2001). Missing data. Sage Publications.

Anderson, P. M., & Levine, P. B. (1999). Child care and mothers’ employment decisions (Working paper no. 7058). National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w7058.

Andrén, T. (2003). The choice of paid childcare, welfare, and labor supply of single mothers. Labour Economics, 10, 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(03)00004-6.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press.

Asai, Y., Kambayashi, R., & Yamaguchi, S. (2015). Crowding-out effect of publicly provided childcare: Why maternal employment did not increase (ISS discussion paper series F-177). University of Tokyo.

Auspurg, K., & Hinz, T. (2015). Factorial survey experiments. Sage.

Avellar, S., & Smock, P. J. (2003). Has the price of motherhood declined over time? A cross-cohort comparison of the motherhood wage penalty. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00597.x.

Baker, M., Gruber, J., & Milligan, K. (2008). Universal child care, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. Journal of Political Economy, 116(4), 709–745. https://doi.org/10.1086/591908.

Barslund, M., Rand, J., Tarp, F., & Chiconela, J. (2007). Understanding victimization: The case of Mozambique. World Development, 35(7), 1237–1258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.09.018.

Bauernschuster, S., & Schlotter, M. (2015). Public child care and mothers’ labor supply—Evidence from two quasi-experiments. Journal of Public Economics, 123, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.12.013.

Becker, G. S. (1965). A theory of the allocation of time. The Economic Journal, 75(299), 493–517. https://doi.org/10.2307/2228949.

Becker, G. S. (1974). Is economic theory with it? On the relevance of the new economics of the family. American Economic Association, 64(2), 317–319.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press.

Berger, M. C., & Black, D. A. (1992). Child care subsidies, quality of care, and the labor supply of low-income, single mothers. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 74(4), 635. https://doi.org/10.2307/2109377.

Blau, D., & Currie, J. (2006). Chapter 20 pre-school, day care, and after-school care: Who’s minding the kids? In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education (Vol. 2, pp. 1163–1278). Elsevier. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0692(06)02020-4.

Blau, D. M., & Robins, P. K. (1988). Child-care costs and family labor supply. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(3), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.2307/1926774.

Blau, D. M., & Robins, P. K. (1989). Fertility, employment, and child-care costs. Demography, 26(2), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061526.

Blau, D. M., & Tekin, E. (2007). The determinants and consequences of child care subsidies for single mothers in the USA. Journal of Population Economics, 20(4), 719–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0022-2.

Blau, F. D., Ferber, M. A., & Winkler, A. E. (2006). The economics of women, men, and work (5th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

Boeri, T., & van Ours, J. C. (2008). The economics of imperfect labor markets. Princeton University Press.

Brewer, M., Cattan, S., Crawford, C., & Rabe, B. (2016). Does more free childcare help parents work more? (IFS working paper W16/22). Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1920/wp.ifs.2016.1622.

Bukodi, E., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2013). Decomposing ‘social origins’: The effects of parents’ class, status, and education on the educational attainment of their children. European Sociological Review, 29(5), 1024–1039. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs079.

Cameron, C. A., & Trivedi, P. K. (2009). Microeconometrics using Stata. Stata Press.

Cascio, E. U., Haider, S. J., & Nielsen, H. S. (2015). The effectiveness of policies that promote labor force participation of women with children: A collection of national studies. Labour Economics, 36, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2015.08.002.

Cattan, S. (2016). Can universal preschool increase the labor supply of mothers? IZA World of Labor. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.312.

Chiappori, P.-A. (1992). Collective labor supply and welfare. Journal of Political Economy, 100(3), 437–467. https://doi.org/10.1086/261825.

Chiuri, M. C. (2000). Quality and demand of child care and female labour supply in Italy. Labour, 14(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9914.00126.

Cleveland, G., Gunderson, M., & Hyatt, D. (1996). Child care costs and the employment decision of women: Canadian evidence. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 29(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.2307/136155.

Collett, J. L., & Childs, E. (2011). Minding the gap: Meaning, affect, and the potential shortcomings of vignettes. Social Science Research, 40(2), 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.08.008.

Connelly, R. (1992). The effect of child care costs on married women’s labor force participation. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 74(1), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/2109545.

Connelly, R., & Kimmel, J. (2003). Marital status and full-time/part-time work status in child care choices. Applied Economics, 35, 761–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/0003684022000020841.

Creedy, J., & Kalb, G. (2005). Discrete hours labour supply modelling: Specification, estimation and simulation. Journal of Economic Surveys, 19(5), 697–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0950-0804.2005.00265.x.

Davis, E. E., Carlin, C., Krafft, C., & Forry, N. D. (2018). Do child care subsidies increase employment among low-income parents? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39(4), 662–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9582-7.

Del Boca, D., & Vuri, D. (2007). The mismatch between employment and child care in Italy: The impact of rationing. Journal of Population Economics, 20, 805–832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-006-0126-3.

Ecoplan. (2016). Betreuungsgutscheine in der Stadt Bern. Evaluation des Pilotprojekts. Schlussbericht. http://www.buero-communis.ch/fileadmin/Dateien/Dokumente/pdf/04%2020160418%20Stadt%20Bern%20Schlussbericht_Betreuungsgutscheine.pdf.

Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. (1986). Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Statistical Science, 1(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1214/ss/1177013817.

Federal Statistical Office. dem Arbeitsmarkt. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfsstatic/dam/assets/1061095/master.

Federal Statistical Office. (2017). Strukturerhebung. Bundesamt für Statistik. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/erhebungen/se.assetdetail.2348805.html.

Federal Statistical Office. (2019a). Bilanz der ständigen Wohnbevölkerung nach Bezirken und Gemeinden, 1991–2018. Federal Statistical Office. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfsstatic/dam/assets/9486056/master.

Federal Statistical Office. (2019b). Schweizerische Arbeitskräfteerhebung (SAKE). Teilzeiterwerbstätigkeit in der Schweiz 2017. Federal Statistical Office. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfsstatic/dam/assets/7106889/master.

Federal Statistical Office. (2020a). Beschäftigungsgrad. Federal Statistical Office. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfsstatic/dam/assets/11987465/master.

Federal Statistical Office. (2020b). Erwerbsquoten nach Geschlecht, Nationalität, Altersgruppen, Familientyp. Federal Statistical Office. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfsstatic/dam/assets/12127223/master.

Gerfin, M., & Lechner, M. (2002). A microeconometric evaluation of the active labour market policy in Switzerland. The Economic Journal, 112(482), 854–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00072.

Graafland, J. J. (2000). Childcare subsidies, labour supply and public finance: An AGE approach. Economic Modelling, 17(2), 209–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-9993(99)00029-2.

Guest, R., & Parr, N. (2013). Family policy and couples’ labour supply: An empirical assessment. Journal of Population Economics, 26, 1631–1660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0421-0.

Haan, P., & Wrohlich, K. (2011). Can child care policy encourage employment and fertility? Evidence from a structural model. Labour Economics, 18, 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2010.12.008.

Hardoy, I., & Schøne, P. (2015). Enticing even higher female labor supply: The impact of cheaper day care. Review of Economics of the Household, 13, 815–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9215-8.

Havnes, T., & Mogstad, M. (2011). Money for nothing? Universal child care and maternal employment. Journal of Public Economics, 95, 1455–1465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.05.016.

Heckman, J. J. (1974). Effects of child-care programs on women’s work effort. Journal of Political Economy, 82(2, Part 2), S136–S163. https://doi.org/10.1086/260297.

Heckman, J. J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312(5782), 1900–1902.

Herbst, C. M. (2010). The labor supply effects of child care costs and wages in the presence of subsidies and the earned income tax credit. Review of Economics of the Household, 8(2), 199–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-009-9078-1.

Kimmel, J. (1998). Child care costs as a barrier to employment for single and married mothers. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(2), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465398557384.

Kornstad, T., & Thoresen, T. O. (2006). Effects of family policy reforms in Norway: Results from a joint labour supply and childcare choice microsimulation analysis. Fiscal Studies, 27(3), 339–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2006.00038.x.

Kornstad, T., & Thoresen, T. O. (2007). A discrete choice model for labor supply and childcare. Journal of Population Economics, 20(4), 781–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0025-z.

Lefebvre, P., & Merrigan, P. (2008). Child-care policy and the labor supply of mothers with young children: A natural experiment from Canada. Journal of Labor Economics, 26(3), 519–548. https://doi.org/10.1086/587760.

Lefebvre, P., Merrigan, P., & Verstraete, M. (2009). Dynamic labour supply effects of childcare subsidies: Evidence from a Canadian natural experiment on low-fee universal child care. Labour Economics, 16, 490–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.03.003.

Leibowitz, A., Klerman, J. A., & Waite, L. J. (1992). Employment of new mothers and child care choice: Differences by children’s age. The Journal of Human Resources, 27(1), 112–133. https://doi.org/10.2307/145914.

Lokshin, M. (2004). Household childcare choices and women’s work behavior in Russia. The Journal of Human Resources, 39(4), 1094–1115. https://doi.org/10.2307/3559040.