Abstract

We examine how means-tested childcare subsidies affect parental labor supply. Using the introduction of reduced childcare prices for low-income families in Norway in 2015, we show that these subsidies may have the unintended effect of discouraging work rather than promoting employment. First, structural labor supply simulations suggest that a negative parental labor supply effect dominates, ex ante. Ex post, we find a small and insignificant effect of means-tested childcare subsidies on parental labor supply in the reform year. We find no statistically significant bunching around the income limits in subsequent years, but we do find negative labor supply effects in subsequent expansions of the reform. Our results suggest that in a context where both parental employment and participation in formal childcare are high, means-tested childcare subsidies may have unintended parental labor supply effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Policy makers in industrial countries have made considerable efforts to increase public childcare provisions and curb parental fees. In Europe and North America, governmental support for childcare is high on the political agenda. Proponents argue that access to universal childcare will promote female employment by helping reconcile work and family responsibilities, as well as enhancing child development (OECD 2021). However, how childcare subsidies should be designed and whether they should be means-tested remain important and recurrent policy questions.

In the present study we analyze a Norwegian reform that introduced reduced childcare prices for low-income households in 2015. The stated argument for targeting childcare subsidies at low-income families was to boost childcare enrollment and encourage employment among parents with initially low participation rates. However, an unintended effect of means-tested support is that it raises the effective marginal tax rates and participation tax rates in the income interval in which subsidies are being phased out and thus discourages work. In this study, we refer to these conflicting effects as the “price” and “strategic” effects of means-tested childcare subsidies.

The novel contribution of this study is to separate the price- and strategic effects empirically and to warn against the potential negative impacts of means-tested childcare price reductions on parental labor supply. We bring together two key empirical approaches. First, we demonstrate that a structural labor supply model estimated on detailed survey data before the reform (Thoresen and Vattø 2019) is a valuable starting point to quantify the expected price- and strategic effects of the reform, ex-ante. Second, we use the Norwegian reform as a unique setting to estimate the price and strategic effects, respectively, by taking quasi-experimental approaches to administrative register data. We estimate the price effect using a regression discontinuity (RD) approach on the first-year unexpected allocation of reduced prices and study strategic effects by evaluating bunching (Saez 2010; Kleven 2016) in subsequent years around the notch in parents’ budget constraints created by the reform. Furthermore, we analyze strategic effects by applying an event study approach in which the event reflects the month when parents unexpectedly learned that they were eligible for reduced childcare prices in the future.

Our findings suggest that the introduction of means-tested childcare subsidies in Norway did not encourage but discouraged parents from working. The simulation results reveal that the strategic effect is expected to be larger than the price effect in the Norwegian context. In the quasi-experimental analysis, we find a small insignificant price effect of the opposite sign than intended, suggesting the income effect may dominate, and no statistically significant bunching around the income limit. However, a negative strategic effect, in which parents reduced their labor supply slightly, is evident in the months following the announcement of the scheme. The latter finding illustrates that strategic effects can also be present in the absence of observed bunching.

The analysis in this paper speaks to two main branches of the literature, which have not previously been combined to study the overall labor supply effects of means-tested childcare subsidies. First, there is significant research on the price effects of subsidized childcare focusing on how childcare can be seen as a fixed cost of work for the mother (Blau and Currie 2006). Several studies find positive effects of reduced childcare prices on maternal labor supply (Cascio 2009; Fitzpatrick 2010; Bauernschuster and Schlotter 2015; Brewer et al. 2022). However, in contexts with high female employment and unrestricted access to childcare, previous studies suggest limited effects of prices on parental labor supply (Lundin et al. 2008; Simonsen 2010; Black et al. 2014; Bettendorf et al. 2015; Hardoy and Schøne 2015; Akgunduz and Plantenga 2018). Still, the effect may be larger for subgroups with initially lower participation rates, such as single mothers, individuals with low levels of education, immigrants, or large families (Gelbach 2002; Cascio 2009; Drange and Telle 2015; Givord and Marbot 2015). It should also be mentioned that related studies focusing on childcare participation and child development suggest that participation in formal childcare may have positive effects on child development, especially for children from disadvantaged families (Duncan et al. 2023).

Second, a substantial amount of public finance research has considered how income taxes discourage labor supply (Blundell and MaCurdy 1999). Based on previous research in this field, increases in the effective marginal tax rates and participation tax rates usually discourage labor supply. In other words, although tax and transfer changes induce both an income effect and a substitution effect, according to Slutsky’s decomposition, the substitution effect typically dominates. Maternal labor supply is more responsive than paternal labor supply to financial incentives, although the gender differences have decreased over time (Blau and Kahn 2007). An important distinction is the effects on the extensive (participation decision) and intensive margin (hours of work) of labor supply (see, e.g., Heckman 1993), where a number of influential studies have suggested that the extensive margin responses are large (Eissa and Liebman 1996) whereas the intensive margin responses are relatively small (Blundell and MaCurdy 1999). Various studies have found evidence of reduced labor supply by means-tested transfers of family support, including Brewer et al. (2010), Eissa and Hoynes (2011), Chan and Moffitt (2018), Boer et al. (2022), and Rees et al. (2023). However, the negative labor supply effects of means-tested childcare subsidies have rarely been studied.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the institutional background of childcare in Norway, the introduction of the means-tested scheme, and the expected price and strategic effects. Section 3 describes the structural model estimated to fit the behavior of Norwegian families to quantify the predicted effects of the reform. Section 4 demonstrates how the introduction and later expansions of means-tested childcare subsidies serve as a unique natural experiment for analyzing the price and the strategic effect, respectively. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 Institutional background and hypotheses

2.1 Institutional background

Publicly provided childcare has a long history in Norway. It was expanded in the early 1970s and through the 1980s and reached coverage rates of nearly 60 percent among three- to six-year-olds by 1990 (Havnes and Mogstad 2011). However, the demand for formal childcare exceeded the supply, and in 2003, policy makers formalized their efforts to increase the supply of childcare centers through the so-called “childcare compromise.” The agreement included a plan for full childcare coverage and a substantial reduction in parental payments, regulated by a maximum price set by the authorities each year. The maximum price regulation is implemented for all childcare centers, regardless of whether the childcare center is owned privately or by the municipality.Footnote 1 Children may enroll in formal childcare from the year they turn one until they start school (the year they turn six). As the enrollment process follows the school year, availability for one-year-olds is highest in August.Footnote 2

In the years after the agreement to increase childcare availability in 2003, coverage rates rose sharply. Since 2010, childcare coverage has stabilized at a relatively high level, and in 2022, 97 percent of children aged three to five years old and 88 percent of children aged one to two years old were enrolled in childcare centers (Statistics Norway 2023). However, certain groups have lower enrollment rates. A survey on families’ childcare preferences in 2016 showed that enrollment rates for children aged three to five years old are 93 percent among low-income families (Moafi 2017). Although there is no requirement for parents to work to qualify for formal childcare, group differences are closely related to the mother’s labor market attachment. Childcare enrollment is highest in families where the mother is employed and works full-time.Footnote 3 The availability of part-time places is limited, and most families pay for a full-time place even when the child spends less than full-time in the childcare center (see, e.g., Moafi 2017).Footnote 4 Only five percent of enrolled children aged three to five years old pay for part-time childcare, although low-income families are overrepresented with 11 percent in part-time childcare (Moafi 2017).

Childcare prices, measured as a percentage of the average wage, are low in Norway compared to most other countries (OECD 2020) and the parental payment covers less than 25% of the cost (Lunder 2015), with the remaining part subsidized by the government. In 2015, the maximum parental payment was set to 2580 NOK per month for the first child in formal childcare.Footnote 5

2.2 Reduced parental childcare prices for low-income families

In 2015, the national scheme for reduced parental payment for low-income families was announced and implemented. The objectives of the reform were to increase enrollment for low-income families and to reduce child poverty (Innst. 14 S (2013–2014)). As a result, the reform should also contribute to achieving the political and societal goal of high labor market participation to ensure that families can provide for themselves. The scheme applies to all childcare centers in Norway and is administered at the municipal level and financed by the government.

Prior to the national scheme in 2015, municipalities had already been required to provide reduced price schemes for low-income families, but in 2011 only 22 percent offered such schemes (Statistics Norway 2012). Even those municipalities that provided income-graded parental payment offered a less generous scheme than that introduced in 2015. In many cases, the household income requirements was below NOK 300,000 and less than three percent of enrolled children received reduced parental payment based on their income (TNS Gallup 2011).Footnote 6 A survey of the rollout showed that 12 percent of municipalities had additional local schemes to supplement the national scheme of moderations, while 88 percent complied with the national requirement (Trætteberg and Lidén 2018). The reform in 2015 therefore represented a distinct change in access to reduced childcare prices for low-income families and a shift from various (less generous) local systems to a nationwide minimum requirement.

The national means-tested scheme consists of two parts: First, parental payment for one child should not exceed six percent of household income. Based on the maximum price for parental payment, this implied that families with yearly household incomes lower than NOK 473,000 were eligible for reduced parental payment when the reform was announced in May, 2015. Second, low-income families with a yearly household income lower than NOK 405,000 were entitled to 20 h per week of childcare free of charge for four- and five-year-olds. This essentially means that families entitled to both schemes first received a payment reduction and then received free part-time (20 h) off the reduced price, corresponding to half of the reduced price for full-time enrollment.Footnote 7 The free part-time scheme for low-income families was later extended to include three-year-olds in 2016 (announced in June, 2015) and two-year-olds in 2019. Currently, families must apply for reduced parental payment which is granted for one school year (August–July) at a time. Eligibility for both subsidy schemes is based on the household’s total taxable earnings and capital income,Footnote 8 which is documented by the tax return information for the previous calendar year.

We illustrate the means-tested scheme for parental prices in Fig. 1. First, PMAX is the price for childcare required from families before the reform. This is also the price for families with household income above the set income limit after the introduction of the means-tested scheme. Next, the reduced payment scheme of a maximum of six percent of household income creates a kink in the price and the parent’s budget constraint at IRP. In families that do not have children in the age group that may qualify for free part-time childcare, the price will follow the first part of this downward sloping line until zero. Families with children in the age group that qualify for free part-time childcare with an income level below IFPT pay a reduced price from PFPT=0 to PFTP=1, and they will pay only 50 percent of full-time childcare, leading to a discontinuity in the price (and budget constraint) at income-level IFPT. This means that the same household is strictly worse off (in terms of disposable income after childcare expenses) earning income just above the cutoff IFPT compared to just below. For lower income levels, the price is reduced gradually to comply with the rule of six percent of household income minus the 20-h free part-time attendance. Figure 1 also depicts the density of household income prior to the reform; about one-fifth of households had income below IRP.

A graphical illustration of the means-tested price scheme. Note: An illustration of full-time childcare expenses (for one child in the eligible age group) at the vertical axis and families’ income on the horizontal axis. The price of childcare increases with household income according to the regulation that childcare expenses should make up a maximum of six percent of household income, until the maximum price (PMAX) of childcare is reached at the income level IRP (NOK 473,000 in 2015). In addition, the regulation of free part-time attendance applies when household income is lower than IFPT (NOK 405,000 in 2015), reducing the price for full-time attendance to half from PFPT=0 to PFPT=1. The dark blue long-dash-dotted line reflects the density of household income prior to the reform

2.3 Expected labor supply effects

We distinguish between two main expected effects of means-tested childcare subsidies relative to a flat price for all, which we refer to as the price effect and the strategic effect. The price effect is the effect of reduced childcare prices which entails both a substitution effect and an income effect for low-income families. The substitution effect is expected to make it more attractive to work as childcare expenses, which can be seen as a fixed cost of working, are reduced (Blau and Currie 2006). Thus, both childcare participation and labor market participation are expected to increase. The magnitude of the substitution effect depends on how sensitive childcare demand is to price reductions and how strong the link is between childcare demand and labor supply. The substitution effect of the price reduction can only be effective for families that are not yet using childcare. The income effect works in the opposite direction: reduced prices for low-income families who are already using childcare implies that they will be able to afford more of all goods including leisure.

Previous empirical estimates of the price effect indicate that the substitution effect dominates the income effect, which suggests that reduced prices will have a positive effect on parental labor supply. However, the magnitude of the income effect relatively to the substitution effect is likely to depend on the initial childcare coverage. If there is close to full childcare coverage, as in the Norwegian context, then there is less scope for a substitution effect and more scope for an income effect. Although the substitution effect is often found to be most effective at the extensive margin (whether to participate in the labor market), there is also a possible substitution effect at the intensive margin as there is not necessarily a fixed link between parental labor market participation and children’s participation in childcare. The income effect can also theoretically be both at the extensive and intensive margins, although it is predominately expected at the intensive margin (hours of work).

The strategic effect arises because of means-testing. In other words, the strategic effect arises if an individual’s labor supply decision will have an effect on their eligibility for reduced childcare prices.Footnote 9 When accounting for the fact that prices are increasing with income, means-tested childcare subsidies increase the effective marginal tax rate as well as the participation tax rate: therefore, they may discourage parental labor supply both at the intensive (hours worked) and extensive margins. Therefore, introducing reduced childcare prices for low-income households may theoretically both promote and discourage parental labor supply. In the remaining part of the paper, we analyze the intended price effect and the unintended strategic effect empirically by using structural model simulations (Section 3) and quasi-experimental identification techniques (Section 4).

The structural model simulations quantify the theoretical predicted effects ex-ante in the Norwegian context, which already has high rates of participation in childcare. The quasi-experimental methods evaluate the effects of the reform, ex-post, using administrative register data. In the latter case, the results may be influenced by information frictions and other frictions in the labor market that the structural model assumes away. Regarding potential imperfect information, Trætteberg and Lidén (2018) report some variation in how actively municipalities provided information about the new price scheme to recruit more children from low-income families to participate in childcare centers. The minimum requirement was that municipalities inform families about reduced prices either once they submit an enrollment application or through contact with the center where the child is enrolled. The quasi-experimental approach may also uncover other potential responses in terms of underreporting income without “real” changes in labor supply earnings. However, as earnings and most other income components are third-party reported in Norway, we expect limited scope for misreporting in the current context.

3 Simulations of a structural labor supply model

To quantify the expected effects of the means-tested childcare price scheme, we develop and estimate a behavioral model with simultaneous choice of labor supply and childcare. We demonstrate that the model simulations serve as a valuable ex-ante starting point for understanding the expected importance of the price effect relative to the strategic effect in the context we study.

3.1 The net financial gains of the means-tested childcare scheme

Before estimating the behavioral model, we construct a (non-behavioral) tax and childcare calculator to describe the net financial gains and incentives that the reform created. The calculator takes into account childcare expenses for all children in the household, as well as tax deductions for childcare expenses and childcare support for single parents.Footnote 10 It follows that although all families with children in the eligible age group gain half the price at the income threshold (IFPT), as depicted in Fig. 1, the net price change in absolute NOK (the difference between PFPT=0 and PFPT=1) differs between families.

As an example, for couple households with one child in the four- to five-year-old age groups, the price change at the discontinuity (IFPT) corresponds to savings of approximately NOK 12,150 in 2015 prices (approx. USD 1215) for one child for the childcare year 2015/2016. The financial gain in this case is equivalent to nearly four percent of disposable household income at the relevant income threshold.Footnote 11 Further details on the size of the financial incentives of the reform are reported in Appendix A. Below, we estimate a model to quantify how the means-tested childcare scheme, relative to the initial flat price scheme, is expected to affect labor supply responses.

3.2 The behavioral model: specification and estimation

The behavioral model framework is influenced by several studies that use the discrete choice formulation in a standard labor supply setting (Aaberge et al. 1995; van Soest 1995; Dagsvik et al. 2014; Dagsvik and Jia 2016) and in a joint labor supply and childcare choice setting (Kornstad and Thoresen 2007; Apps et al. 2016; Gong and Breunig 2017; Thoresen and Vattø 2019; Boer et al. 2022; Boer and Jongen 2023).

Following Thoresen and Vattø (2019),Footnote 12 we argue that parents’ choice of labor supply and childcare realistically can be viewed as a discrete choice problem, where the choice is made from a set of combinations of jobs in the labor market and slots in childcare centers. We let \(z( z=1, 2,...)\) index the combinations of childcare and job pairs. Each combination is characterized by \((h,q)\), where \(h=({h}_{m},{h}_{f})\) denotes hours of work for mother and father, respectively, and \(q\) the childcare time that is bought.Footnote 13 Disposable income (consumption) for each job and child care combination is given by the budget constraint, \(C=f\left(h,q\right)\), where \(f\; (.)\) is a function that transforms wage income and choice of childcare into disposable income after childcare expenses, given the households individual offered wage rates and nonlabor income.

Next, we take into account that parents face restrictions in their choice of jobs, following Dagsvik et al. (2014) and Dagsvik and Jia (2016). We let \(b(h)\) represent the number of job opportunities in the choice set \(B(h)\) available to the household with working hours equal to \(h\).

In a random utility framework of revealed preferences, parents’ decisions are represented as the result of a maximization problem, where the utility function is assumed to have the following structure:

where \(v\left(.\right)\) is the deterministic part of the utility function, whereas \(\varepsilon \left(z\right), z=1, 2,...,\) are independent and identically distributed (iid) random terms with cumulative distribution function (cdf) \({\text{exp}}\left(-{\text{exp}}\left(-x\right)\right)\). It then follows that the probability of a household to choose a set of jobs and care alternatives with observed characteristics equal to \((h,q)\) is given by

In our empirical specification, we simplify the maximization problem by letting each household choose among four alternatives for working hours, \({h}_{k}=\left\{{h}_{k,none},{h}_{k,part},{h}_{k,full}, {h}_{k,over}\right\}\), for mother (k = m) and father (k = f) and among three alternatives for childcare, \(q=\left\{{q}_{none},{q}_{part},{q}_{full}\right\}\), which refers to contractual time in childcare over the calendar year. Thus, wage-earner couples have \(4\cdot4\cdot3=48\) observed alternatives, single wage-earner households have \(4\cdot3=12\) observed alternatives, and households where neither parent is a (potential) wage earner choose among only the three childcare alternatives. For each household, we compute disposable income for each of the possible discrete choice combinations of working hours and childcare, following from the budget constraint.Footnote 14

We further specify that the systematic part of the utility function is separated into three parts:

We let \({v}_{1}\left(C\right)={\alpha }_{0}C+{\alpha }_{1}{C}^{2}\) and \(C={w}_{m}{h}_{m}+{w}_{f}{h}_{f}+I-t\left({w}_{m}{h}_{m}, {w}_{f}{h}_{f},I\right)-p\left(q\right),\) where \({w}_{k}\) is the wage rate for the mother (m) and father (f), respectively. I is the nonlabor income of the household, \(t\left({w}_{m}{h}_{m}, {w}_{f}{h}_{f},I\right)\) are taxes levied on the household, and \(p(q)\) is the childcare price.

Further, we assume \({v}_{2}\left(h\right)={\beta }_{1}{X}_{m}{\text{log}}(\overline{T }-{h}_{m})+{\beta }_{2}{X}_{f}log(\overline{T }-{h}_{f})+{\beta }_{3}log(\overline{T }-{h}_{m})log(\overline{T }-{h}_{f})\), where \(\overline{T }\) denotes a constant for total hours available (assumed to be 80 h per week) that the individual can split into working hours and leisure.

Finally, \({v}_{3}\left(h,q\right)=({\gamma }_{0}{X}_{q}+{\gamma }_{1}{log{l}_{m}+\gamma }_{2}log{l}_{f})q\), where \({X}_{m}, {X}_{f},\) and \({X}_{q}\) denote a set of observable taste modifiers of preferences for mothers’ leisure, fathers’ leisure, and childcare. We let both \({X}_{m}\) and \({X}_{f}\) include an intercept and a dummy for low and high education, whereas \({X}_{q}\) includes an intercept and the age of the child (one to five years old). We thus do not impose a fixed link between the mother’s working hours and the childcare bought in the market (which has been the usual assumption in earlier “traditional” models of mothers’ labor supply and childcare demand) but rather estimate the relation as interaction terms.Footnote 15

For single parents, the specification is simplified by excluding the terms involving \({l}_{m}\) or \({l}_{f}\). For households in which neither parent is classified as a (potential) wage earner, the parents are left with the decision on the level of q by maximizing the utility of the terms \({v}_{1}\left(C\right)\) and \({\gamma }_{0}{X}_{q}q\).

Opportunities are specified by the expression \(logb\left({h}_{m},{h}_{f}\right)={g}_{m }\,{h}_{m,full}+{g}_{f }\,{h}_{f,full},\) where \({h}_{k,full}\) is equal to 1 in the full-time working alternative and 0 otherwise for mothers (m) and fathers (f), respectively. This represents the presumably larger mass of full-time jobs (relative to other time arrangements) available in the market and is assumed to be unaffected by exogenous changes in budget constraints.

We use the method of maximum likelihood to estimate the parameters of the utility function and the opportunity measure, which means that parameters are chosen such that the probability of the observed choices that households make is maximized. In the estimation sample, we thus need exact information about the childcare choices households make in the pre-reform period. Therefore, we rely on data from the Childcare Survey 2010, which maps childcare preferences for about 3000 households (Moafi and Bjørkli 2011; Wilhelmsen and Löfgren 2011). The survey includes detailed information on family composition, the main activity/labor market status of parents, socioeconomic background, and mode/intensity of childcare.Footnote 16 Information on reported income (wages, transfers, etc.) and tax payments is obtained from administrative records, such as Income and Wealth Statistics for Households (Statistics Norway 2022) and linked to the Childcare Survey by personal identification numbers. We estimate separate models for couples and for singles/couples where only one, or neither, parent is classified as having flexible labor supply.Footnote 17

The estimated parameters of the model are reported in Appendix A. We find that the estimated model has the expected properties according to economic theory, with positive marginal utility of both disposable income (consumption) and leisure. We also find that parents, on average, have positive preferences for childcare (as a normal “good”). As expected, we find a negative interaction between preferences for leisure and childcare. This interaction is stronger for mothers than for fathers, which suggests that the choice of childcare is more connected to the mother’s decisions regarding working hours than to the father’s.

Note that the underlying assumption of the model is that the parameters of the utility function and opportunity expression are unaffected by the alternative policies. The model can thus describe how changes in prices, \(p\left(q\right),\) taxes and transfers, \(t\left({w}_{m}{h}_{m}, {w}_{f}{h}_{f},I\right),\) or wages, \({w}_{m},{w}_{f}\), will affect individuals’ optimal decisions regarding \((h,q)\) as described in our simulation results.

3.3 Simulation results

To obtain representative simulation results, we extrapolate the estimated behavioral model to the complete Norwegian population of families with children in the one- to five-year-old age group in the (pre-reform) year 2014. We thus map information on household composition and individual characteristics obtained from administrative records. First, we use the estimated parameters of the wage regression (see Table A.2 in the Appendix) and inflate them to a 2014 level to obtain a predicted wage rate for each individual, which we use to obtain disposable income for each hypothetical combination of working hours and childcare in the household.Footnote 18 Second, we use Eq. (2) with the estimated model parameters to obtain a probability distribution for each combination of working hours and childcare for each household.

We use a flat price scheme (PMAX for all in Fig. 1) as the benchmark in all simulations, which is set at NOK 2510 per month, or NOK 27,610 per year, for all families (measured in 2014-NOK).Footnote 19 In all simulations, we present average effects for households with the youngest child in the two- to five-year-old age groups.Footnote 20

First, in Table 1, we present standard response elasticities. Estimates are obtained from simulations in which the wages of the mother, the wages of the father, and childcare prices, respectively, are increased by one percent from the benchmark. We find that the wage elasticities are in line with earlier research, with larger elasticities for mothers than for fathers. While the cross-wage elasticities are small, the wage of the parents (especially the mother) has a positive impact on the childcare demand. The elasticity of childcare demand with respect to price is also small: when the price is increased by one percent, demand is reduced by 0.04 percent. Similarly, prices have close to zero effect on the labor supply of parents, 0.01 percent for mothers, and even lower for fathers. However, note that a percent increase in prices is a very small amount in NOK as prices are already rather low in the benchmark.

We now turn to our main simulation results, which describe how the introduction of means-tested childcare prices affects the probability distribution of the alternatives and thus the expected working hours supply and childcare demand of the households. Again, we use the flat price scheme (PMAX for all) as the benchmark and compare this to the means-tested price scheme described in Fig. 1. To be specific, we compare the means-tested price regulation in 2015 with a benchmark with the same maximum price level but without the means-tested reductions in prices. As the income limits in 2015 refer to the previous year’s income (2014), the levels are not adjusted. For the means-tested price, we thus keep IRP at NOK 473,000 and IFPT at NOK 405,000 in the simulations.Footnote 21

To separate the price effect and the strategic effect that the reform induces, we distinguish between two different simulation scenarios. In the first scenario, childcare prices are means-tested with respect to observed household income in 2014. This means that a subset of families will gain access to reduced childcare prices regardless of how they respond to the new scheme in terms of labor supply decisions. The simulation results of this scenario thus trace out the pure price effect of the reform. In the second scenario, low-income households are endogenously determined in the model by parents’ labor supply decisions; parents take into consideration that their labor supply decisions will affect their childcare expenses. The second scenario thus represents the net effect of the reform, including both price and strategic effects.

The results on labor supply and childcare demand of the two scenarios are reported in Table 2.

In the first scenario, we find that the price effect of reduced childcare prices on parents’ labor supply is very small on average, but with a positive sign. This suggests that the substitution effect is larger than the income effect of the price change. As expected, the effect is largest for mothers. In the second scenario, where household income is determined endogenously by parents’ labor supply decisions, the effect on labor supply turns from positive to negative. This suggests that the negative strategic effect dominates the positive price effect, thus leading to our main result that, on average, means-tested childcare prices discourage parents from working.

In Table 3, we demonstrate the effect of the same two simulations on the probability of eligibility for reduced prices. Consistent with the finding that the price effect has a positive effect on labor supply for fixed (pre-determined) low-income households, we find a small negative effect on the probability of being characterized as a low-income household after the behavioral adjustment (− 0.19%). Conversely, when income is endogenously determined by parents’ labor supply, the probability of being characterized as a low-income household increases, reflecting the strategic effect that it is relatively more attractive to be below the income limit to gain access to reduced prices. Again, the size of the effect is modest: 0.24% more households are eligible for the reduced price schedule than in the benchmark with flat prices.

Finally, it is worth remarking that the behavioral simulation model builds on a stylized theoretical framework with possible limitations. First, it is a static (one period) framework in which families face a trade-off between consumption and leisure without any time dimension. In this setting, the price and strategic effects are functional over the same period, and responses are independent of how long a family is affected by the means-tested scheme. Furthermore, the model framework assumes rational agents, no labor market frictions, and full information. Nevertheless, this static ex-ante simulation analysis provides a valuable starting point for our quasi-experimental identification of the reform, as presented in Section 4. In Appendix D, we also present a validation exercise that demonstrates that the model simulations match the quasi-experimental results quite closely.

4 Quasi-experimental evidence of the price effect and the strategic effect

The introduction of the means-tested scheme in 2015 offers a unique setting for estimating the price effect, that is, the effect of reduced childcare prices. The subsequent expansions of the scheme also enable the identification of strategic adjustments to meet the income requirement for reduced parental payment in the future (the strategic effect). When the means-tested scheme was announced in May, 2015, eligibility status for free part-time childcare for families with four- and five-year-olds (born in 2010 and 2011) was pre-determined and tied to the already realized household income in 2014. Therefore, the household could not change their eligibility status in 2015 through income manipulation. Households with children born in 2011–2014 or later were informed about future access to free part-time childcare and could make behavioral adjustments to gain or maintain eligibility. Put differently, these families could adjust their labor supply and household income in 2015 and 2016 to become or remain eligible for free part-time childcare in 2016 and 2017. Such adjustments are what we call the strategic effects of the mean-tested childcare subsidy.

Using administrative register data, we first estimate the price effect for families with children born in 2010 and 2011 by regression discontinuity (RD) around the income limit for eligibility. Then we describe and contrast two empirical strategies for recovering the strategic effects of means-testing on parental labor supply: First, we evaluate bunching around the income threshold (IFPT in Fig. 1) after the reform was introduced. Second, exploiting the fact that new cohorts are included in the means-tested scheme in subsequent years, we the use an event study approach to investigate broader strategic labor supply responses. All parameters capture intention-to-treat effects (ITT) since they measure the effect of being eligible for free part-time childcare.

The data are compiled from several Norwegian administrative records, including income registers, educational registers, and family and employment registers for all residents on January 1 each year. Our dataset includes detailed information on individuals aged 15 years or older. Families are identified by a unique link between mother and child and the other parent. Most of our data are annual and follow the calendar year, while the income limit for eligibility is set in August and applies for the school year (August–July). Eligibility is based on the previous year’s tax records, which is consistent with the observed income in our data.Footnote 22 Administrative information on childcare enrollment is not directly observed, but indirectly through parents’ tax deductions for childcare expenses (which are pre-filled in the parents’ tax returns).Footnote 23

4.1 Evaluating the price effect on parental labor supply

In our main analysis, we include the universe of households with at least one child aged four to five years old in 2015—which was the target age group for free part-time childcare when the nationwide scheme was first implemented. Our assignment variable is household income, which is the aggregate of the mother’s personal taxable income and the personal taxable income of her partner, if any. Personal taxable income includes earnings, pensions, taxable welfare benefits such as sick pay, disability or unemployment benefits, and positive capital incomes. We normalize household income by \({I}_{i,t-1}=\frac{{HI}_{i,t-1}-{c}_{t}}{{c}_{t}}\), where \({HI}_{i,t-1}\) is household income and \({c}_{t}\) is the relevant cutoff income. The normalized family income, \({I}_{i,t-1},\) will be 0 at the cutoff and takes positive values above and negative values under the cutoff.

To evaluate the price effect, we employ a standard RD analysis where we compare the employment outcomes of parents whose income is just below the cutoff to those whose income is just above the cutoff. For each labor supply outcome \({y}_{i}\), we estimate the following model:

where \({y}_{i,t}\) denotes the outcome for individual i at year t, \(D=1\cdot\left\{I_{i,t-1}>0\right\}\) is an indicator for whether the income of household i is above the cutoff, \({I}_{i,t-1}\) is the assignment variable, \({x}_{i}\) is a vector of predetermined control variables, and \({\varepsilon }_{i,t}\) is the conventional error term. The estimate of interest is \({\beta }_{1}\), which is the effect of having income above the cutoff, that is, not being eligible for free part-time childcare, on the outcome. Positive estimates imply that eligibility for free part-time childcare has negative effects on labor supply, and vice versa.

We estimate both maternal and paternal labor supply effects. We consider the effects on overall labor supply (including non-participants) and distinguish between the effects on the extensive margin (employed/non-employed) and the intensive margin (hours per week). A person is considered employed if he/she is registered as an employee and received a non-zero and non-negative wage. Others are considered non-employed. Individuals are assigned a category based on their employment spells in the relevant period from August, 2015, through July, 2016. Hours per week measures the average of weekly hours worked when the individual is employed, while overall labor supply is weekly hours including the zeroes. This measure captures both the extensive and the intensive margin.

Households just above and just below the cutoff differ in their eligibility for free part-time childcare (half price for full-time attendance), but we assume that they are similar in all other observable and unobservable predetermined dimensions. To test the validity of these identification assumptions, we check two potential threats to identification: strategic income manipulation and compositional differences between the treatment and control group. The results of these checks are provided in Fig. B.1 and B.2 and Table B.2 in Appendix B. We find no evidence of manipulation of the assignment variable in our RD framework and no observed differences in the pre-determined covariates for households just above or just below the cutoff. Thus, it seems credible that differences in labor market outcomes around the cutoff can be interpreted as the causal effect of reduced childcare prices. The validity of our research design also assumes that the inclusion of covariates should have little effect on our estimates, other than a potential increase in precision. We confirm that including a set of pre-determined variables (pre-first birth) does not change our results in Table B.3.

In our main specification we run an RD model with a linear spline function in the assignment variable and triangular weights.Footnote 24 We follow Calonico et al. (2014) and choose optimal bandwidths, that is, bandwidths that optimize the mean-squared-error from the RD treatment effects around the income cutoff for all our labor supply outcomes.

Figure 2 graphically presents the main results of our RD analysis on the impact of free part-time childcare on the three measures of labor supply for the mother (panels a–c) and her partner (panels d–f). Each circle represents conditional mean values of the representative variable for each bin (10 groups) and the corresponding 95 percent confidence interval. The solid line is the fitted value from a local linear regression with the optimal bandwidth. The vertical line is the cutoff point in the assignment variable (normalized income). The estimated discontinuity at the cutoff is reported in the title of every panel, and the corresponding regression results are presented in Table 4. These results suggest that there is little evidence that entitlement to free part-time childcare leads parents to work more. We find no significant discontinuities around the cutoff in any of our labor supply measures at the extensive or intensive margins.

Effects of childcare subsidies on labor supply. Note: Circles represent the conditional mean values of the representative variable for each bin (10 groups) and capped spikes represent the 95 percent confidence interval. The solid line is the fitted value from a local linear regression with the optimal bandwidth. The vertical line is the cutoff point in the assignment variable

Moreover, positive point estimates suggest that parents who are eligible for free part-time childcare work less than parents who are not eligible for reduced prices. The confidence intervals around the estimates reveal that a positive effect of the reduced childcare prices on parents’ labor supply is either non-existing or very small. Regarding maternal employment, a doubling of the price of childcare leads to a change in maternal employment of 0.007 ± 0.0392, which implies that cutting the price in half at most increases maternal employment by 0.03 percentage points, corresponding to a labor supply elasticity with respect to the childcare price of maximum 0.09 with 95 percent certainty.Footnote 25

These findings are not sensitive to inclusion of pre-determined covariates, different functional forms, alternative bandwidths, or the exclusion of large cities with similar subsidy schemes before the reform, as reported in Tables B.3–B.5 and Fig. B.3 in Appendix B. Interestingly, the cohort-specific regressions presented in Table B.5 in Appendix B reveal a positive significant estimate for the 2010 cohort, which implies a significant reduction in labor supply. The effect is mainly found on the intensive margin (working hours) which could indicate that the income effect dominates. A possible reason for the substitution effect being even smaller than predicted by the simulation model could be the lack of information spread among families who were not already participating in childcare.Footnote 26

Therefore, our main take-away from the RD analysis is that if the reform encourages parents to work because of reduced prices, the effect is minor. Our point estimates are positive, suggesting that the price effect slightly reduces parental labor supply, but not significantly different from zero in our main specification.

The observed insignificant results on parents’ labor supply could be associated with non-response in childcare demand or by a weak connection between childcare participation and parents’ labor supply. Unfortunately, we do not have information on childcare enrollment directly but use tax deduction for childcare expenses as a proxy for childcare enrollment. We test the first mechanism using imputed childcare enrollment as the dependent variable using an RD approach. Again, we find insignificant results (see Fig. 3). Enrollment in childcare decreases by two percentage points when households have access to free part- time childcare, with a 95 percent confidence interval of ± 3.1 percentage points. According to these estimates free part-time care increases childcare participation by at most 1.1 percentage points with 95 percent certainty, corresponding to a price elasticity of childcare use of maximum of 0.05.Footnote 27 This suggests that the price effect on childcare utilization is low and insignificant, which confirms that the substitution effect of reduced childcare prices is minor both in terms of childcare demand and parental labor supply.

The effect of eligibility for childcare subsidies on childcare use. Note: Circles represent the conditional mean values of the representative variable for each bin (10 groups) and capped spikes represent the 95 percent confidence interval. The solid line is the fitted value from a local linear regression with the optimal bandwidth. The vertical line is the cutoff point for the assignment variable. Bias-corrected estimate and robust standard error in parentheses. Childcare use is imputed using observed tax-deduction for childcare expenses

4.2 Evaluating the strategic effect

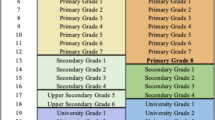

After the implementation in 2015, the means-tested childcare subsidy was continued and expanded to include younger age groups. First, in 2015, families with children born in 2010 and 2011 were eligible for free part-time childcare. The 2010 cohort experienced a pure price effect, while the 2011-cohort experienced both a price and a strategic effect initially, since these parents could adjust their labor supply in the remainder of 2015 to become or remain eligible in 2016. The price and strategic effects across birth cohorts and over time are visualized in Fig. 4. The 2012 cohort was not a targeted group for the subsidy in May, 2015, but they could in theory adjust their labor supply to reduce/not increase their household income to become/remain eligible for free part-time childcare in the future. From May, 2015, until December, 2015 these families could adjust their labor supply to gain eligibility for the subsidy in 2016. Labor supply adjustments in 2016 would affect eligibility in 2017. As shown in Fig. 4, these families have a pure strategic effect from May to December, 2015, and from January to July, 2016. Then in August, 2016, they experience both price and strategic effects. The 2013 cohort knew in May, 2015, that they could become eligible for free part-time childcare attendance in August, 2017, based on their child’s age and could adjust their labor supply in 2016 to become eligible for the subsidy in August, 2017. However, in June, 2016, as the government announced an expansion of the moderation scheme to include three-year-olds, the 2013 cohort gained unexpected access to free part-time attendance in August, 2016. Thus, these families experience both strategic and price effects after August, 2016. In June, 2016, the families of children born in 2014 knew that they could adjust their income in 2016 to gain eligibility in 2017. These families had a pure strategic effect from July, 2016, to December, 2016, in relation to the subsidy in 2017 and from January, 2017, to August, 2017, in relation to the subsidy in 2018.

Strategic and price effects for eligible households (2015–2017). Note: Numbers in headers represent month of the year. Numbers in the left column represent the birth cohort. Periods with purely strategic effects are marked in red, periods with both strategic and price effects in green, and periods with purely price effects in yellow. Periods of anticipation of future strategic effects are in gray

To investigate the strategic effects of the means-tested childcare subsidy, we expand our observation period from 2015 to 2017 and include households with children born in 2010–2014 in the data. We first check for possible strategic adjustments in household income just below the cut-off IFPT in Fig. 1 (e.g., Kleven 2016). Formally, we perform McCrary density tests (Cattaneo et al. 2017, 2020) for household income in 2015 and 2016, respectively, and test for bunching around the income limit.Footnote 28 We include all relevant cohorts with either a pure strategic effect or a combined strategic and price effect (see Fig. 4). Our results in Fig. 5 show that the estimated differences in the density functions at the cutoffs are insignificant in 2015 and 2016.These findings provide few signs of bunching below the cutoff among relevant cohorts for the income years 2015 and 2016, indicating that the strategic effects are limited and that individuals do not misreport income on their tax returns just below the income threshold to gain eligibility. However, there is a clear spike in the density to the left of the cutoff for the 2011–2012 cohorts in 2015. We provide several placebo and robustness checks in Appendix C (Figs. C.1–C.3) which find no sign of a similar spike in income in other years or in other birth cohorts. The uniqueness of this spike in 2015 might suggest that households are adjusting to the income limit for reduced childcare prices despite the insignificant estimate at the discontinuity. Working hour regulations, for instance, may prevent individuals from adjusting just below the household income limit of reduced prices. If individuals choose among a discrete set of jobs, as in the structural model simulations in Section 3, rather than optimizing working hours at the margin, we will not observe bunching even if people do strategically adjust (as shown in Appendix D).

Non-parametric density test of local strategic manipulation of household income in 2015 and 2016. Note: These figures and tests were generated by the STATA-command rddensity with default options on our sample of households and plot range (− 0.4; 0.4) around the cutoff. The estimated discontinuity coefficient and p-value in parentheses

To separate out the strategic effect in more detail, we utilize the panel structure of our monthly data and the introduction and further expansions of the means-tested scheme, in an event study approach, allowing for leads and lags around the time of expansions of the scheme.

We estimate the following equation:

Where \({Y}_{i,g,m,,t}\) is the labor supply for individual i in group g, in month m and year t. \({\lambda }_{t}\) is the year fixed effects, \({\theta }_{m}\) the month fixed effects, and \({\gamma }_{i}\) is the individual fixed effect capturing constant differences between individuals. \({D}_{i,t}^{\ell}\) is the indicator for unit i being \(\ell\) months away from initial treatment, \({\mu }_{\ell}\) is the estimated treatment effect, and \({\nu }_{i,t}\) is the error term. Our set-up has two treatment periods (May, 2015–June, 2016, and June, 2016–July, 2017) and two treatment cohorts (2012 and 2014).Footnote 29 We use three months before treatment as the pre-period.Footnote 30 As the control group, we use households without children. These families are clearly not eligible for the childcare subsidy but are otherwise relatively similar to the treatment group (see balance tests presented in Appendix C). We have restricted our sample to households where the woman is 25–55 years old. In this way, we reduce the role of labor supply decisions among relatively young and old individuals. This restriction reduces the sample size in our control group, which lowers the precision of our results, but does not change our main conclusion (see Table C.2 in Appendix C). We apply a panel event study model corresponding with a difference-in-difference model with a series of estimated leads and lags relative to the time of treatment.

The outcome of interest is labor supply in terms of employment and hours worked.Footnote 31 A central question is how large the labor supply adjustments must be for the estimated strategic effects to be meaningful. For instance, the mean income level among single mothers is well below the income limit in both years, while more than 90 percent of partnered households have income levels that are higher than the limit (densities shown in Fig. C.4 in Appendix C). In fact, on average, mean hourly wages and mean work hours in our sample indicate that a partnered mother could reduce her annual wage income in 2015 by NOK 209,000 after May, 2015, if she withdrew from the labor market for the rest of the year. However, this would not be enough to give the average household eligibility and would require the partner to adjust their labor supply as well. Given the size of the subsidy (less than 10 percent of this income reduction), the labor supply adjustment is most relevant for households near the cutoff. We therefore include households with incomes lower than or equal to two times the income limit.

Table C.1 in Appendix C reports the means and standard deviations of background and outcome variables for the treatment and control group for all, and for single and partnered mothers separately. Women in the control group have longer education than the treatment group, possibly reflecting investments in higher education in the control group. The treatment group is to a larger extent of immigrant background, possibly reflecting the higher fertility rate among immigrants as well as immigrant’s higher representation among low-income families. Also, the share of single households is higher in our control group. These observable differences are expected since the control group consist of non-parents. We account for constant observable differences between treatment and control by adding individual fixed effects in the analysis, as well as performing separate analysis for single and partnered and for immigrants and low educated. Another concern is that women without children are on different labor supply trends than women with children, violating the parallel trend assumption of the difference-in-difference framework. We believe that this is less of a concern in the Norwegian context where employment rates among women are generally high, and where employment rates among women without children and mothers have been stable at around 80 percent since 2010 (Statistics Norway 2019). Additionally, stable insignificant pre-trends in our main analysis and in the robustness checks where we allow for separate trends for treatment and control suggest that the parallel trend assumption holds.

Our main results on the strategic effects are reported in Figs. 6, 7, and 8. Separate analyses for immigrants and low educated as well as robustness checks allowing for different trends in the treatment and control groups are provided in Appendix C, Figs. C.5–C.7, C.8–C.10, and C.11–C.13, respectively. We find an immediate negative strategic effect on labor supply for single mothers, primarily driven by adjustments in the extensive margin, but these estimates switch sign and become positive and significant six months after treatment. Among partnered mothers, we find clear negative strategic effects immediately after treatment for overall labor supply. The effect is primarily driven by adjustments on the intensive margin. We find immediate negative effects on employment, but these estimates are relatively small compared to the effect on the intensive margin. The effect on employment switches sign after six months, but still these estimates are small in magnitude. We therefore conclude that partnered mothers adjust their labor supply, primarily on the intensive margin. Evaluated at the mean for partnered mothers in the treatment group (28 h per week), a point estimate of − 1 represents a 3.5 percent reduction in working hours per week in this group. For partners, we find a clear negative immediate effect on working hours after the announcement of the scheme which remains negative until one year after treatment. Evaluated at the mean for partnered mothers in the treatment group (34 h per week), a point estimate of − 1.75 represents a 5 percent reduction in working hours per week.

Strategic effects for single mothers. Difference-in-difference estimates on overall labor supply, employment and hours worked. Note: These figures present the point estimate and the corresponding 95 percent confidence interval on lags and leads from an event-difference-in-difference model, where time = 0 is the time of treatment. The treatment group is individuals aged 25–55 in households with children born in 2012 or 2014. The control group is individuals aged 25–55 in households without children. The model includes year, month, and individual fixed effects

Strategic effects for partnered mothers. Difference-in-difference estimates on overall labor supply, employment, and hours worked. Note: These figures present the point estimate and the corresponding 95 percent confidence interval on lags and leads from an event-difference-in-difference model, where time = 0 is the time of treatment. The treatment group is individuals aged 25–55 in households with children born in 2012 or 2014. The control group is individuals aged 25–55 in households without children. The model includes year, month, and individual fixed effects

Strategic effects for the partner. Difference-in-difference estimates on overall labor supply, employment, and hours worked. Note: These figures present the point estimate and the corresponding 95 percent confidence interval on lags and leads from an event-difference-in-difference model, where time = 0 is the time of treatment. The treatment group is individuals aged 25–55 in households with children born in 2012 or 2014. The control group is individuals aged 25–55 in households without children. The model includes year, month, and individual fixed effects

Our results suggest that couples adjust their working hours in the months following the announcement of the scheme. Reductions in working hours are the main driver behind the labor supply response, while employment effects are negative in the immediate months after treatment and turn positive after six months. We suspect that these and other positive effects 6–7 months after treatment reflect adjustments to a new income tax year. Separate analyses on households where the mother is immigrant or has low education demonstrate qualitatively similar results (see Figs. C.5–C.7 and C.8–C10). Allowing for separate trends in the treatment and control group in Figs. C.11–C.13 confirm that the immediate negative strategic effect is robust for potential differences in trends between treatment and control, although the positive effects in later periods are lower and/or insignificant in these specifications. This confirms that our results are robust across groups and specifications and signifies that strategic responses are present although couples are not able to adjust just below the income limit for reduced childcare prices.Footnote 32

5 Conclusion

Introducing reduced childcare prices for low-income families induces both a price effect and a strategic effect, where the former is the effect of reduced childcare prices and the latter the effect of means testing by household income. First, the price effect entails both a substitution effect and an income effect for the targeted low-income families. The substitution effect is expected to make it more attractive for parents to work as childcare expenses, which can be seen as a fixed cost of working, are reduced (Blau and Currie 2006). The income effect works in the opposite direction as reduced prices for low-income families already using childcare should allow them to afford more of all goods, including leisure. Thus, the price effect is not necessarily positive, although this was the intended effect of reduced childcare prices. Second, an unintended strategic effect results from the phaseout of childcare subsidies by household income, which creates high effective marginal tax rates and high participation tax rates and thus reduces parents’ incentives to work.

We study these conflicting price and strategic effects on parental labor supply in relation to the introduction of reduced childcare prices for low-income families in Norway in 2015, using structural model simulations and quasi-experimental identification approaches. The simulation results suggest that the price effect is positive but dominated by the negative strategic effect, which means that the ex-ante expected effect of the reform on parental labor supply is negative. When using post-reform administrative data with a RD design, we find insignificant negative price effects on first-year outcomes, which suggest that either the price effect is indeed negative (the income effect is larger than the substitution effect) or the true positive price effect is very small. We find no significant bunching below the income threshold for reduced childcare prices in subsequent years, but a difference-in-difference event study approach reveals negative strategic effects after the announcement of the reform for couples. We conclude that reduced childcare prices for low-income families may have discouraged rather than encouraged parental labor supply in Norway.

Previous studies have already suggested that when the childcare participation rates are high, there is little scope for a further increase in parents’ labor participation and childcare demand by reducing prices further. We add to the existing literature by demonstrating that reducing childcare prices for low-income families may in fact discourage overall parental labor supply. The main implication of our study is thus that policy makers should be aware of the potential negative impacts on parental labor supply when introducing means-tested childcare subsidies. Especially in a context with already high rates of childcare participation, such as Norway, the negative effect on parental labor supply is likely to dominate.

We leave further topics on means-tested childcare subsidies for future research. First, although we show that a static model framework is likely to quantify the most important dimensions of parental labor supply, captured by the relatively short-term quasi-experimental evidence, further dynamic dimensions with regard to altered fertility decisions, intertemporal substitution, and gradual adjustment are possible avenues for future research on longer-term effects. Second, although we find limited effects on childcare participation, the reform clearly acts as a redistributional device that reduces the out-of-pocket expenses of low-income families using childcare, which may have a positive impact on families’ wellbeing and child development.

Data availability

This paper presents results based on data drawn from Norwegian administrative registers and Norwegian surveys. Due to data confidentiality requirements, we are unable to upload the datasets. Researchers can gain access to the data by submitting a written application to the data owners. Applications must enclose Data Protecting Impact Assessment (DPIA) which should be approved by a data protection officer. Conditional on this approval, Statistics Norway will then determine which data one may obtain in accordance with the research plan. Inquiries about access to data from Statistics Norway should be addressed to mikrodata@ssb.no. More information is available at https://www.ssb.no/en/omssb/tjenester-og-verktoy/data-til-forskning.

Notes

Each municipality is required to provide public subsidized childcare, although the owner of the facility does not need to be the municipality itself. As such, 52 percent of the childcare centers in Norway are privately owned and receive public subsidies on a per child basis (Statistics Norway 2023).

Since 2016–2017, children born after August—in September, October, or November—have a statutory right to a place in a childcare center by the month the child turns one. Children born later in the school year have a legal right to a place from August when they have turned one.

According to Moafi (2017) about 85 percent of mothers with one or two children in the age group three- to five-year-olds participate in the labor market.

The opening hours are usually restricted to about nine hours during the day on weekdays, and most children spend less than full-time in childcare centers.

Families with more than one child in childcare receive a sibling rebate of 30 percent for the second child and 50 percent for the third child and further children.

Prior to the 2004 agreement that included a maximum-price for parental payment, means-testing was much more widespread in the municipalities. At that time 67 percent of municipalities reported that they that had a low-income price reduction scheme (Statistics Norway 2003).

If the household is entitled to a sibling rebate, this is deducted prior to the free part-time deduction.

The households include spouses and registered partners or cohabitants in addition to children. If a child lives permanently with one parent, means-testing is based on the income in the household where the child is registered as resident.

If eligibility is based on last calendar year’s income, as in the Norwegian context, an individual’s labor supply decision today will have an effect on their next year’s eligibility.

Childcare expenses are tax deductible up to a maximum threshold. Single parents may be entitled to programs that entitle them to have two-thirds of their childcare expenses covered; in this case, the financial gain of receiving free part-time attendance is lower.

Disposable household income (after taxes) at the income threshold are about NOK 320,000.

The model used in Thoresen and Vattø (2019) also included the decision between daytime work and shift work. This dimension is ignored in the present version. Furthermore, we use contractual time in childcare over the calendar year rather than reported time in care in the present version of the model. We further differ from Thoresen and Vattø (2019) in estimating adjusted models for all household types, not only for couples.

For simplicity, we model parents’ childcare decision for the youngest child (one- to five-years-old) in the household. Older siblings’ childcare expenses are included in the parents’ budget constraint.

Each individual is assigned an individual specific wage rate per hour; see further details in Appendix A.

The more traditional approach treats mothers’ care as the only alternative to paid care; see, e.g., Blau and Currie (2006).

The primary reason for relying on survey data to estimate the model is that we need detailed data about childcare choices, which will be less accurately imputed in the administrative data.

Parents are classified as having flexible labor supply if they are not registered as students, unemployed (not voluntary), self-employed, or the recipient of parental leave payments.

A detailed tax-benefit model is used to simulate disposable income for each alternative combination. We extend Statistics Norway’s tax-benefit model LOTTE-Skatt to simulate childcare expenses for each of the choice alternatives, taking into account sibling moderation, income moderation, “cash for care,” tax deductions for childcare spending, lone parents’ transitional benefits, and support for childcare expenses.

This corresponds to the maximum price in 2015, deflated to the 2014 NOK.

For simplicity, we exclude one-year-olds (measured at the end of the calendar year) as they do not have a statutory right to a place in a childcare center over the whole calendar year.

Note that the six percent rule still applies to the nominal maximum price level in 2015 of NOK 2580 per month/NOK 28,380 per year.

If a household experiences drastic changes in their income, for example, due to unemployment, disability, divorce, or death, they may apply for and receive the subsidy if they are able to document their new situation. Information of this kind is not available to us in our registers.

This means that we cannot link the deduction to a specific child or observe childcare uptake in the situation when parents have no taxable income and/or when parents use childcare free of charge, only. When comparing our imputed measures of participation to aggregate measures of childcare participation, we somewhat underestimate childcare participation.

We use the rdrobust command in STATA (Calonico et al. 2017).

The elasticity is computed as follows: An increase of 0.03 percentage point in maternal participation from a level of approximately 0.7 amount to a 4.6 percent increase. Since prices decrease by 50 percent at the cutoff, the labor supply elasticity with respect to the price level is no more than 0.09 in the expected negative direction with 95 percent probability.

As mentioned in Section 2.2, Trætteberg and Lidén (2018) describe differences in municipality recruitment strategies. Some low-income families who had not used childcare centers before may not have been sufficiently informed about the reduced prices, which could potentially reduce the estimated substitution effect.

A 0.011 increase in childcare use at 0.8 uptake, amount to a 1.4 percent increase. Since prices decrease by 50 percent at the cutoff, the price elasticity is no more than 0.03 in the expected direction. Note that there is no theoretical explanation for why parents would use childcare less when prices are reduced. In contrast to the price effect on parents’ labor supply; both the income effect and the substitution effect would cause parents to use more formal childcare.

We use the rddenstiy command in STATA.

Common to the families of the 2012 and 2014 birth cohorts is that there was no anticipation of the treatment, while the 2013 cohort knew 8 months in advance that they could adjust their labor supply and income from January, 2016. The latter violates the non-anticipation assumption of the event study framework, so we exclude this cohort from our analysis.

The monthly employment data starts in January, 2015 when A-ordningen was implemented in Norway. We exclude January, 2015, in the analysis because of very low data quality due to the break in data collection. Consequently, we have a three-month pre-period.

Since wages account for 96 percent of mothers’ average personal taxable income and 85 percent of their partners’, adjustments in labor supply are essential for changes in income level.

Note that we interpret the findings as strategic effects, although we cannot rule out other dynamic effects of the future expected price effect in terms of intertemporal substitution or gradual adjustment, as briefly discussed in Section 3.4.

References

Aaberge R, Dagsvik JK, Strøm S (1995) Labor supply responses and welfare effects of tax reforms. Scand J Econ 97(4):635–659

Akgunduz YE, Plantenga J (2018) Childcare prices and maternal employment: a meta-analysis. J Econ Surv 32(1):118–133

Apps P, Kabátek J, Rees R, van Soest A (2016) Labor supply heterogeneity and demand for childcare of mothers with young children. Empir Econ 51(4):1641–1677

Bauernschuster S, Schlotter M (2015) Public childcare and mothers’ labor supply - evidence from two quasi-experiments. J Public Econ 123:1–16

Bettendorf LJ, Jongen EL, Muller P (2015) Childcare subsidies and labour supply—evidence from a large Dutch reform. Labour Econ 36:112–123

Black SE, Deverieux PJ, Løken KV, Salvanes KG (2014) Care or cash? The effect of childcare subsidies on student performance. Rev Econ Stat 96(5):824–837

Blau DM, Currie J (2006) Pre-school, day care, and afterschool care: who’s minding the kids? Handbook of the economics of education. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Blau FD, Kahn LM (2007) Changes in the labor supply behavior of married women: 1980–2000. J Labor Econ 25(3):393–438

Blundell R, MaCurdy T (1999) Labor supply: a review of alternative approaches. Handbook of Labor Economics 3:1559-1695

Boer HW, Jongen ELW (2023) Analysing tax-benefit reforms in the Netherlands using structural models and natural experiments. J Popul Econ 36:179–209

Boer HW, Jongen ELW, Kabatek J (2022) The effectiveness of fiscal stimuli for working parents. Labour Econ 76:102152

Brewer M, Cattan S, Crawford C, Rabe B (2022) Does more free childcare help parents work more? Labour Econ 74:102100

Brewer M, Saez E, Shephard A (2010) Means-testing and tax rates on earnings. In: Adam S, Besley T, Blundell R, Bond S, Chote R, Johnson GMP, Myles G, Poterba J (eds) Dimensions of tax design: the mirrlees review, pp 90–174. Oxford University Press

Calonico S, Cattaneo M, Titiunik R (2014) Robust nonparametric confidence intervals for regression-discontinuity designs. Econometrica 82(6):2295–2326

Calonico S, Cattaneo M, Farrell MH, Titiunik R (2017) rdrobust: software for regression-discontinuity designs. Stata J 17(2):372–404

Cascio EU (2009) Maternal labor supply and the introduction of kindergartens into American public schools. J Hum Resour 44(1):140–170

Cattaneo MD, Jansson M, Ma X (2017) rddensity: manipulation testing based on density discontinuity. Stata J 18(1):234–261

Cattaneo MD, Jansson M, Ma X (2020) Simple local polynomial density estimators. J Am Stat Assoc 115(531):1449–1455

Chan MK, Moffitt R (2018) Welfare reform and the labor market. Annu Rev Econom 10:347–381

Dagsvik JK, Jia Z, Kornstad T, Thoresen TO (2014) Theoretical and practical arguments for modeling labor supply as a choice among latent jobs. J Econ Surv 28(1):134–151

Dagsvik JK, Jia Z (2016) Labor supply as a choice among latent jobs: unobserved heterogeneity and identification. J Appl Economet 31(3):487–506

Drange N, Telle K (2015) Promoting integration of immigrants: effects of free childcare on child enrollment and parental employment. Labour Econ 34:26–38

Duncan G, Kalil A, Mogstad M, Rege M (2023) Investing in early childhood development in preschool and at home. In: Hanushek E, Machin S, Woessmann L (eds) Handbook of the Economics of Education, vol 6, pp 1–91

Eissa N, Liebman JB (1996) Labor supply response to the earned income tax credit. Q J Econ 111(2):605–637

Eissa N, Hoynes H (2011) Redistribution and tax expenditures: the earned income tax credit. Natl Tax J 64(2):689–729

Fitzpatrick MD (2010) Preschoolers enrolled and mothers at work? The effects of universal pre-kindergarten. J Law Econ 28:51–85

Gelbach JB (2002) Public schooling for young children and maternal labor supply. Am Econ Rev 92(1):307–322

Givord P, Marbot C (2015) Does the cost of childcare affect female labor market participation? An evaluation of a French reform of childcare subsidies. Labour Econ 36:99–111

Gong X, Breunig R (2017) Childcare assistance: are subsidies or tax credits better? Fisc Stud 38(1):7–48

Hardoy I, Schøne P (2015) Enticing even higher female labor supply: the impact of cheaper day care. Rev Econ Household 13(4):815–863

Havnes T, Mogstad M (2011) No child left behind: subsidized childcare and children’s long-run outcomes. Am Econ J Econ Pol 3:97–129

Heckman JJ (1993) What has been learned about labor supply in the past twenty years? Am Econ Rev 83(2):116–121

Innst. 14 S (2013–2014) https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Publikasjoner/Innstillinger/Stortinget/2013-2014/Inns-201314-014/ (in Norwegian). Accessed 15 Aug 2023

Kleven HJ (2016) Bunching. Ann Rev Econ 8:435–464

Kornstad T, Thoresen TO (2007) A discrete choice model for labor supply and childcare. J Popul Econ 20(4):781–803

Lunder T (2015) Nasjonale satser til private barnehager. TF-notat nr 97/2015. Telemarksforsking, Bø i Telemark (in Norwegian)

Lundin D, Mörk E, Öckert B (2008) How far can reduced childcare prices push female labour supply?. Labour Econ 15(4):647–659

Moafi H (2017) Barnetilsynsundersøkelsen 2016. En kartlegging av barnehager og andre tilsynsordninger for barn i Norge. Statistics Norway (in Norwegian)

Moafi H, Bjørkli ES (2011) Barnefamiliers tilsynsordninger, høsten 2010. Oslo. Statistics Norway (in Norwegian)

OECD (2021) Education at a Glance. OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en

OECD (2020) Is childcare affordable? Policy brief on employment, Labour and Social Affairs, Paris. https://www.oecd.org/els/family/OECD-Is-Childcare-Affordable.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2023

Rees R, Thoresen TO, Vattø TE (2023) Alternatives to paying child benefit to the rich: means testing or higher tax? Aust Econ Rev 56(3):328–354

Saez E (2010) Do taxpayers bunch at kink points? Am Econ J Econ Pol 2(3):180–212

Simonsen M (2010) Price of high-quality daycare and female employment. Scand J Econ 112(3):570–594

Statistics Norway (2003) Undersøking om foreldrebetaling i barnehagar, august 2003. https://www.ssb.no/a/publikasjoner/pdf/notat_200377/notat_200377.pdf (In Norwegian). Accessed 15 Aug 2023

Statistics Norway (2012) Undersøking om foreldrebetaling i barnehagar, januar 2012. https://www.ssb.no/a/publikasjoner/pdf/rapp_201219/rapp_201219.pdf (In Norwegian). Accessed 15 Aug 2023