Abstract

Causal relationships are traditionally examined in quantitative research. However, this article informs the discussion surrounding the potential use of qualitative data to explore causal relationships qualitatively through an empirical illustration of a school leadership development team. As school leadership development is supposed to offer continuing development to practicing school leaders, it brings into question the issue of causal relationships. This study analyzes audio and video recordings from 10 workshops involving a team of principals, municipality leaders, and researchers who met over two years to support the principals in leading a local school improvement program. The process data are organized into episodes and analyzed in three layers of causation an interpretative layer, a contradictory layer, and an agentive layer grounded in cultural-historical activity theory. When tracing a problem statement across episodes and relating the processes to events in a principal practice, causal relationships became visible across the episodes and contexts. The argument, then, is that the results are achieved in the processes. As such, process data can reveal causal relationships that quantitative data cannot.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Causal relationships are traditionally examined in quantitative research, although some researchers (Miles and Huberman 1989; Miller and Fredericks 1987) have attempted to reestablish both the legitimacy and potential of causal and qualitative analyses of empirical data. This article informs the discussion surrounding the potential use of qualitative data to explore causal relationships qualitatively through an empirical illustration of school leadership development.

Every year, organizations spend considerable amounts of money training their leaders (Day 2011). The training might take place through “the education of leaders" (settings where aspiring and practicing school leaders are enrolled in programs that confer formal qualifications) or through “school leadership development” (workshops, partnerships, and project teams that offer continuing development to practicing school leaders but do not bestow formal qualifications). When society is spending a large amount of money on educating and developing leaders, it is reasonable for many stakeholders to show an interest in knowing whether leadership development works in terms of instilling better leadership practices. This concern is also relevant when it comes to the development and education of school leaders, where participants in school leadership development are supposed to use what they have learned in daily practices as school leaders.

For many years, the research on the education of school leaders and school leadership development was dominated by "the theory movement" in the USA, which aimed to develop generic laws for school leadership that could, in turn, be used as a standardized knowledge base in the professionalization of school leaders (Griffiths 1988). The movement's distinction between facts and values was highly criticized and ultimately dismantled (Greenfield 1979; Greenfield and Ribbins 1993). The necessity of viewing school leadership from a historical, cultural, and social perspective was underscored (Bates 1984, 2006, 2013). Despite criticism, the movement has been reinvented through the measurement of correlations between leadership and student outcomes. Researchers (see Firestone and Riehl 2005; Leithwood and Jantzi 2008; Mulford and Silins 2003; Simkins et al. 2009) have for years aimed to develop theoretical models that can be used to visualize correlations between factors directly or indirectly influencing student outcomes, with training and organizational learning as several factors.

Many stakeholders, such as foundations, governments, international institutions, and professional associations around the world, have turned their attention to the quality of the formal education of school leaders. Leithwood and Levin (2005) argued that the empirical grounds for making claims about the effects of formal school leadership programs are limited. The New Labour governments in the UK (1997–2010) operated on a correlational link between the education of school leaders and school leadership practices by, for example, setting up the National College of School Leadership. Similar centers around the world (e.g., North America, Europe, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand) began to offer extensive, comprehensive programs for the preparation and development of school leaders from 2000 onward (Hallinger 2003; Huber 2010). Several countries, including the USA, have also developed standards for both leadership and school leadership education (Møller 2009; Young and Perrone 2016; Young et al. 2016). The common assumption is that it is possible to derive standards for the education of school leaders based on knowledge about the best practice of school leadership regardless of the specific leadership role or context. In the Norwegian context, from which this paper draws its empirical data, there are no national standards for best practice of school leadership or for the development or education of school leaders. Albeit, the Norwegian Directorate for Education expects the national school leadership education should imply imprints in terms of changes in school leadership practices as well as in the schools as organizations (Aamodt et al. 2019). Consequently, there is a question of transfer—i.e., whether what is being learned in one context (e.g., on campus) causes better leadership practices in another context (e.g., in schools). Taken together, these issues introduce the question of causal relationships, which is the focus of the present article.

Specifically, the aims of this article are to (1) exemplify how researchers are approaching causality, (2) illustrate how causal relationships become visible in the process data of school leadership development, and (3) discuss the potential of using qualitative process data to make causal relationships visible. To achieve this aim, I draw on process data from a team of principals, municipality leaders, and researchers, hereafter called the Leadership for Improvement Team (LIT). The LIT was part of one of the hundred projects in a national program called the Knowledge Promotion—from Words to Deed, which was part of a national curriculum reform. The national education authority considered the implementation of the curriculum reform to be challenging on an organizational level. Thus, engagement with external institutions, such as colleges and universities, was a prerequisite for the local projects to get funding (Blossing et al. 2010). The team was formed to support the principals in leading the local project in their schools and was considered an arena for school leadership development. There were three pilot schools in the local project.

In the next section, I discuss how researchers are approaching causality before presenting a conceptual framework for analyzing causal relationships in three layers (Engeström 2011) grounded in Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT). Moreover, I describe the empirical setting and methodology of the study before illustrating empirically how causal relationships become visible in the process data of school leadership development. I then discuss the findings in three layers of causation (an interpretative, a contradictory, and an agentive layer) before discussing the potential of using qualitative data and concluding the article.

How are researchers approaching causality?

There are different approaches and views to causality. This section presents three approaches: the regularity approach, the variable approach, and the realist approach (Maxwell 2004a, b).

The regularity approach of causation originated with David Hume (1711–1776), who argued that causal relationships cannot be perceived directly (Maxwell 2004a). What humans can perceive is the “constant conjunction" of events, that is, the regularities in the relationships between events. Hume restricted causation to observable regularities. While the restriction to observable entities was abounded later, causality became related to regularities in data as a matter of whether there are systematic relationships between inputs and outputs.

The variable approach is associated with the variance theory. According to Maxwell (2004a), “Variance theory deals with variables and the correlations among them; it is based on an analysis of the contributions of differences in values of particular variables to differences in other variables” (p. 4). Researchers using the variable approach in their research use experiential or correlational designs, quantitative measurement, and statistical analysis.

The realist approach, however, was developed by Bhaskar (1978) and others who paid attention to events and the processes that connect them, and analyzes of how some events influence others. The realist approach is more likely to be identified in qualitative research because of the attention to processes. This approach holds that causality can be observed and pays attention to the causal mechanism and the processes involved in particular events and situations. Sayer (1992) argued that, “Realism replaces the regularity model with one in which objects and social relations have causal powers which may or may not produce regularities, and which can be explained independently of them” (pp. 2–3). In other words, the focus moves from the regularities to the reality, where both objectsFootnote 1 and social relations are considered to have power. Context is perceived to be intrinsically involved in causal processes, but is not reduced to variables (Maxwell 2004b). Consequently, causality can be observed in the developmental processes in which actors are engaged. Miles and Huberman (1989) use the term “causal realist." The argument is that for a causal realist, the following view is adopted:

Constants or regularities are observable in the social sphere and can be expressed in the form of lawful statements whose validity is independent of individual cognition. Regularities are “out there" to be discovered, whether or not we are aware of them or can articulate them (Miles and Huberman 1989, p. 56).

Over the last decades, researchers have tried to make processes into the building blocks of sociological analyses (Abbott 1992). As Abbott (1992) argued, “For them, social reality happens in sequences of actions located within constraining and enabling structures. It is a matter of particular social actors, in particular social places, at particular social times" (p. 428).

Engeström (2011) positions himself within CHAT, which is conceptualized as a process theory of learning (Engeström and Sannino 2012). CHAT shifts the attention from input and output to the processes of development. The assumption is that the result is achieved in the processes (Engeström 2011), which refers to research processes other than measuring input and output as well as correlations. This article closely examines the developmental processes among members of the LIT by positioning the study in CHAT. The next section outlines some concepts used in the analysis.

A conceptual framework for analyzing causal relationships in three layers

CHAT builds on Vygotsky (1886–1934), who argued that human beings have the will and power to control their behavior with the help of several tools, which are used intentionally internally and externally (Vygotsky 1978). While the unit of analysis in Vygotsky's work in, what Engeström (1987) conceptualizes as the first generation of CHAT, was the “mediated actions” of individuals, “collective activity” was the unit of analysis in Leontév's (1978) work in the second generation of CHAT. Second-generation CHAT moves the attention from individuals to the object-oriented activity of many actors whose work is directed, motivated, and mediated by tools. Objects distinguish one activity system from another (Engeström 1987) and direct and energize activity (Foot 2002).Footnote 2 The present study is positioned within the third generation of CHAT because of its focus on boundary zones (Tuomi-Gröhn et al. 2003) where actors from at least two activity systems interact. In the present study, actors from schools, an educational authority, and a university collaborate in a boundary zone across the three activity systems about leading the local project. While activity systems are developed over a long time, collaborative work in teams, networks, and project groups may exist only for a short time (Engeström 2008), as was the case with the LIT. LIT existed for only two years; consequently, the team is not conceptualized as an activity system. Still, concepts from CHAT can be used for analysis. In this article, I make use of the following concepts (nodes) of the upper part of an activity system: subjects, tools, objects, and outcome:

Subject refers to the individual or subgroup whose position and point of view are chosen as the perspective of the analysis. Object refers to the “raw material” or “problem space" at which the activity is directed. The object is turned into outcomes with the help of instruments, that is, tools and signs. (Engeström and Sannino, 2010 p. 6).

In the current study, the subjects refer to the participant in LIT, and the tools refer to the tools being intentionally introduced and used in the team (cf. Wertsch 2007). I use the term “project object" as an intermediate concept to refer to the problem space in which the activity in the team is directed over two years. The project object consisted of several “situational specific objects.” “The situation-specific reconstruction and instantiation of the object of an activity system takes the form of a problem finding and problem definition" (Engeström 1999, p. 181). A situational specific object refers to what is being worked on here and know, which may shift several times in developmental work.

Engeström (2011) grounded his approach to causality in CHAT when he outlined the three layers of causality in human action. He also built on Escola (1999) when developing the first layer of causality, which is conceptualized as the “interpretative" layer. He then added two more layers, a “contradictory layer" and an “agentive layer,” when searching for causality in process data.

When researchers are examining causality in human action using an interpretative layer, they need to consider that an actor in a specific activity acts based upon the structure and development of an activity—that is, based upon the laws and rules of the activity to which the actors align themselves to make sense of the activity (e.g., if X, then Y) (Engeström 2011). The actors are not considered passive. Rather, an actor is considered to take actions (Y) according to how they perceive the situation (X) based on some logics. From an interpretative layer, researchers can approach causality by studying how actors in activities consider and develop laws and rules based on the principle of “if X, then Y.” It is also an assumption that as participants in collective activities, humans are facing and being driven by multiple contradictory motives in the activity (see Escola 1999), which is a central issue in CHAT (Engeström 1987). Collaborative work in “boundary zones” might be demanding because the different activity systems involved are being driven by different historical objects. When humans face contradictions, they may search for resolutions, often by carrying out unpredictable actions (Engeström 2011). Engeström (2011) added an agentive layer of causality to his framework. The assumption here is that participants in collective activities take intentional transformative actions by intervening with and using artifacts to control the action and direction from the outside.

In all three layers of causality, humans are considered to act based upon their activities, interpretations, and logics (Escola 1999). Consequently, there is a need to pay attention to the processes where developments take place because interactions may make causal relationships visible.

Empirical setting and methodology

The schools in the empirical setting under study had to score themselves using a state-of-the-art template tool as a point of departure for the application for funding. The three pilot schools identified a potential area for improved learning through teaching the students how to approach factual texts with specific learning strategies and creating a culture for learning among staff. The two measures constituted the intended object of the local project. Three principals, one to three leadersFootnote 3 from the local educational authority who were supposed to support the schools in the project, and two researchers from a university in Norway, formed a project team (LIT), which decided that the shared work should be based on some kind of data from the schools (Jensen and Lund 2014). Consequently, several tools, such as video clips from classroom practice, field notes from observations by the principals, and evaluation reports, were introduced to the team (mostly by the researchers) to mediate the processes of leadership development in the team (Jensen and Møller 2013).

The larger study (Jensen 2020; Jensen and Møller 2013; Jensen and Lund 2014), of which the present study is a part, was designed as a longitudinal panel study (Bryman 2012; Cohen et al. 2008). The team consisted of the same people for two years. The overall study sought to examine how leadership development evolved in a team of principals, municipality leaders, and researchers (LIT). The study had a developmental approach, as the researchers were invited to contribute to the local project to support the principals in leading the local project to create a culture for learning. The study also had an interventional approach since the researchers intervened in the team with different types of school data to mediate learning-focused conversations. Eighteen tools were intentionally introduced (cf. Wertsch 2007) to the team (mostly by the researchers). Among those tools were “mirrors." These “mirrors" were based on the observation data from teaching practices in the pilot schools as well as from the leadership practices that summarized what was observed in the teacher and leadership practices (in accordance with the requests from those being observed).

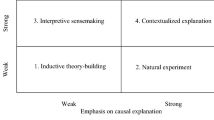

The video and audio data from the 10 workshops constituted the ethnographic data (Heath and Hindmarsh 2002) used in the study. The data corpus consisted of 25 h of audio and video recordings from the team's 10 workshops. The transcriptions of the interactions constitute the departure point of analysis for this article. The data corpus was previously organized into 34 episodes (Jensen and Møller 2013) after careful interaction analysis (Jordan and Anderson 1995) to identify the situational objects and tools being introduced and used (Barab et al. 2001). A new episode was delimited by a start or a thematic shift pertaining to the situational object (what was worked on here and now). Often, an episode started with a question from the researcher combined with the introduction of some kind of tools and questions. The episodes varied in length from 10 to 90 min. I developed criteria for the selection of what Barab et al. (2001) conceptualized as "action relevant episodes" (ARE) for each article in the overall study in relation to the research questions. For this article, I looked for episodes that could illustrate how causal relationships become visible in the process data of school leadership development. I selected seven AREs in which a specific issue was set on the agenda, worked on, and requested. Below, I have marked in bold the episodes in the two-year trajectory of the team that were selected for this article: (Fig. 1).

The analytical process of researching the interactions in the team can be conceptualized as a reconstruction of sequences of episodes and events (cf. Engeström 2011).

A researcher involvement in the unit being researched may challenge the analytical perspective of the research. This limitation is widely discussed in research literature (see, for example, Barab and Kirshner 2001; Goodson 1993). Several strategies were undertaken to secure the quality of the study. For example, all actions and interactions in the team were recorded, transcribed, and coded. The analyses were discussed among many researchers and fed back to the informants. CHAT was selected as the overall theoretical framework for the whole study, which enabled me to provide analyses of the study across the sub-studies within a consistent theoretical framework. There was a time lag between collecting and analyzing the data to create the distance needed to produce critical analysis of the interactions. The need to translate the data from Norwegian to English may represent a threat. To compensate for this threat, the concepts were carefully selected and discussed among researcher colleagues nationally and internationally, and the translations were proofread.

In the next section, I explore how episodes relate across episodes and settings.

Results: how processes relate across episodes and settings

In the next subsections, we meet Casper and Rachael, who are the researchers from a university; Eileen, who is a municipality leader; Tony, who is a principal from a small lower secondary school; Annie, who is a principal in a small primary school; and Billy, who is a principal in a mid-size primary school. The schools are located in rural areas.

The LIT identified a general challenge in Tony's leadership practice

The educational leaders in the municipality arranged teacher seminars for the pilot schools to support the teachers in teaching the students how to read factual texts as one measure in the local project. The researchers observed a staff meeting in Tony's school after one of the teacher seminars (event), and they turned the observation notes into a “mirror.” The mirror should mirror what the observer saw to the one being observed. It contains information about the foci to the problem finder, the purpose, the structure, and the content of the situation, as well as examples and questions of reflection. In the mirror, the researchers listed the teachers' feedback from pair discussions on what they had learned from the previous teacher seminar arranged for the pilot schools.

We met the team in Episode 8 Workshop 3 in a context where the team (the subjects) was asked to analyze the list in the mirror (the tool) to better understand Tony's leadership practice. The mirror materialized the researchers' notes from the staff meeting (an event). Tony explained to LIT that he had attended a group during the teacher seminar, which, according to him, did not accommodate what was requested from the lecturer. Thus, when having a staff meeting at his own school to summarize the teachers experiences from the seminar (an event), rather than asking the teachers how they liked the seminar, Tony asked what the teachers had learned from the seminar as an event. He thus took action to influence the situation using a specific problem statement.

Casper, one of the two researchers, asked LIT to reflect on the list of statements in the mirror (event). Tony expressed that he was happy with what the teachers thought, but when examining the statements on the list, he argued that “many of the statements show that the activities in the seminar were meaningless to the teachers, while other statements show that the teachers had gotten something out of it." Eileen (a municipality leader) agreed: “They are scattered,” and Billy nuanced: “Some of the statements are about their learning, while others are more about how the seminar was organized than what they have learned.” Rachael (one of the researchers) conceptualized the teachers' responses as the “lobster and canary.” She added, “the list does not show that the teachers relate their response to the main focus of the local project” (the students should be better at reading factual texts). Episode 8 shows how a situation in a teaching seminar (an event), a situation in a staff meeting (an event), and the work on a situational object in LIT (episode 8) are related, and how Tony takes action to influence the processes in his school. It also shows how a tool has the power to mediate engagement in teachers' learning (cf. Sayer 1992).

Identifying a specific problem statement related to the math team

Several action learning (AL) sets were incorporated as one of several tools in the LIT to mediate professional learning. One set consisted of the following sequences: (1) identifying a new problem statement to be analyzed in the team, (2) narrowing down the new problem space, (3) asking clarifying questions and deepening the understanding, (4) providing advice (if wanted), (5) identifying further plans for actions, and (6) meta-communicating about the set and sequences (the sequences and the purposes were listed on a sheet available to the participants as a tool). In AL, after the first meeting, sequence 0 is included, in which the facilitator requests any actions taken before working on a new problem statement. Not much time was set aside for this sequence, since most of the time was needed to address a new issue to be worked on. A facilitator led the sequences in AL. In the LIT, the researcher alternated between leading the AL sets.

While the LIT members doubted whether the teachers in general made sense of the seminars (based on the mirror), Tony presented a more specific problem statement in Episode 9: “How to, as a leader, cope with the team of math teachers who do not make sense of the seminars for teachers in the local project." The whole team was invited to ask clarifying questions. Since Tony made it explicit that he would enjoy getting advice, the team members provided advice in the context of what they had heard. Tony received several pieces of advice, such as including the students in the learning community, implementing reflective teams focusing on didactics, being close to the teachers as a leader, sharing excellent practices, and visualizing excellent practice. As shown, Episode 9 relates not only to Episode 8, in which the teachers' statements were examined in the LIT, but also to an event in the teacher seminar and an event in the staff meeting.

In the next section, I present short excerpts where one of the researchers made requests for actions taken since the last workshop (sequence 0).

How Tony tried to transfer a tool from LIT to the math team

In Excerpt 1, we examine the conversation between Rachael and Tony in Episode 15 of Workshop 5 in sequence 0.

Excerpt 1:

Speaker | Utterance | |

|---|---|---|

1 | Rachael | [referring to the sheet with the sequences] Tony, you had some alternatives [advice] to take into consideration [in the last workshop]. Can you please elaborate on it? |

2 | Tony | Yes, so my starting point was how to get the science teachers, especially the math teachers, to use the methodology we learned on the seminar days [for the teachers]. The students [in my school] have inadequate skills in math, they get overly poor grades, and they all feel they are struggling a bit, so I told the LIT I would have a meeting with the math teachers. I asked them [the math teachers] to describe a challenge [Sequence 1 in an AL set]. We selected one of the challenges [for further analyses]. The process did not proceed as requested. I do not think this is typical for math teachers, but this team did not seem to have a tradition of reflecting on what can be done differently to create increased learning [among the students] because there were a lot of descriptions about what the students did, and what they did not do. I asked if they were going to use what they had been taught [in the seminars]I called Eileena, and I said we have to focus on science next year to put more pressure on this group [of teachers]. I thought this was how I should work. I should use half of my time trying to be close to the teachers |

3 | Rachael | Yes, being close was one of the keywords [and pieces of advice] last time [in the workshop]b. Last time we talked about the fact that AL is not only about reflecting but also about following up with actions. Now you have done some actions |

In Excerpt 1, Rachael (1) reminds Tony of the alternatives that were presented to him in Workshop 4. Tony recounts how he tried to incorporate one of the suggested alternatives—that is, being close to the mathematics teachers by entering into their team and organizing an AL set (an event). He transferred a tool introduced in the LIT (in one arena) to his leadership practice in school (in another arena). However, following the advice about being close to the team and facilitating reflective learning did not seem to be an easy task. Tony seemed eager to get the math teachers to make use of the methodologies being taught in the seminars because the students have low scores in math, which can be interpreted as a causal explanation. More specifically, if the teachers teach the students the learning strategies they have been taught at the teacher seminars, the students can improve their results in math. He expected the teachers to reflect on their pedagogies; instead, the teachers were “blaming" the students and their behaviors. Tony's explanation of this matter was that the team lacked a tradition of learning-centered reflection. He took action by requesting that the teachers use what they had been taught and by asking for support from the municipality to focus more on science in the following year to put pressure on the teachers. The logic seems to be that putting pressure on the teachers and collaborating with the municipality would help the situation of poor math scores. When AL did not work as expected, Tony concluded that he should spend half of his time being close to the teachers, which indicates he was forming causal explanations between time and engagement and successful leadership.

As shown, the process in Episode 15 relates to Episodes 8 and 9, and to an event in a teacher seminar being organized in the municipality (where some teachers did not engage) and an event in the teacher seminar being organized in Tony school (where several teachers showed they did not make sense of the teacher seminars) as well as his engagement with the math team where he introduced AL (an event) to influence the culture.

More actions are taken

In Excerpt 2, Workshop 6, Episode 18, we meet the team when the researcher requests Tony to account for any action taken since the last workshop.

Excerpt 2.

Speaker | Utterance | |

|---|---|---|

1 | Rachael | Last time you referred to [in the AL set] being close to the math teachers and making contact with the educational authority in the municipality. Any update? |

2 | Tony | We have made a concrete measure to offer workshops in math for the students |

3 | Rachael | Yes, that is a measure |

4 | Tony | Yes. I consider the math teacher team to be very conservative compared to the other [teacher] teams. I am striving to get them to see the whole problem |

5 | Rachael | And what are your plans for the future? |

6 | Tony | We have organized some more subject-specific teams. They have got some assignments. I plan to be present in some of the meetings to follow up |

In Excerpt 2, the researcher (1) summarizes the actions from the past and asks about actions that have been taken, as well as further plans. Tony (2) presents three new actions that were introduced: workshops for the students, subject-specific teams, and specific assignments. In addition, he intends to follow up more closely. He still refers to the situation as problematic. The argument as to why the situation is difficult is, according to Tony, that “math teachers are conservative” and “they do not see the whole problem," which may relate to the low scores and lack of learning strategies in math (as previously mentioned). Also, in Episode 18, the conversation relates to specific events in Tony's schools, i.e., new conversations with the math team where they do not demonstrate an overall understanding of the problem, and new initiatives directed toward the students (workshops in math) are initiated.

A turning point becomes visible: the math teachers are sharing practices

Excerpt 3 is from Workshop 7, Episode 21; there is still a focus on Tony leadership practice at the beginning of the workshops and any actions taken.

Excerpt 3:

Speaker | Utterance | |

|---|---|---|

1 | Rachael | Have you any updates? |

2 | Tony | I have not had another meeting, but I did have a staff meeting where the teachers presented the students work plans. The math teachers shared how they have reduced the scope and the texts on the work plans for the students. Previously, the math teachers were not engaged in the plenary discussions about learning strategies, but this time they were engaged. I havent been aware of this aspect before now |

Although Tony was not previously close to the math teachers (as he announced in Excerpt 2), it seems that the situation changed for the better, at least according to his considerations. Excerpt 3 indicates that the math teachers tried out new practices to reduce the text in their work plans (event), which may imply that a measure was taken to make the plans more accessible for all students. Compared to before, the math teachers were contributing to the plenary discussions about learning strategies (an event). It seems that Tony became aware of this matter while talking to the team. As mentioned, developing a culture for learning was one of the intended results of the local project. Episode 21 thus related not only to Episodes 8, 9, 15, and 18, but also to other events in Tony leadership practice.

The result after two years

From Episode 18, I jump to the last episode (Episode 34) in Workshop 10, in which the LIT reviews the first two years of the project.

Speaker | Utterance | |

|---|---|---|

1 | Casper | Tony may spend two minutes describing what has happened in the project since the beginning |

2 | Tony | The old culture was that I taught as a teacher and the students got what they could. This has changed a lot. The teachers have been inspired to do new things. All of those things have influenced the culture. There is a greater learning focus in the culture. The students have been given tools and a focus on learning. Now, we are close to an oral exam, and Ive been walking around talking to the students as they sit here and there preparing themselves. It has, in a sense, never been so clear before. Its cool to be good. We are guided more toward the track that is about focusing on learning |

Excerpt 34 indicates that, according to Tony, the local project is considered a success in terms of the students' learning and for the learning culture. Indirectly, the episodes relate to the other episodes presented in this section, but also to many events in his school context.

In the following section, the findings are analyzed in the context of three layers of causation—the interpretative layer, the contradictory layer, and the agentive layer—and discussed in a broader context.

The potential of using qualitative process data to explore causal relationships

When tracing a problem statement across episodes and relating the processes to events in a principals’ practice, causal relationships have become visible across episodes and contexts that cannot be documented from quantitative data. An analysis of the seven episodes has shown evidence of relationships among the episodes. The conversation about how to cope with aspects of a school leader's practice across episodes and contexts continues. The analysis of one episode requires knowledge about the previous selected episode. It also requires knowledge about other relevant events. As shown in the analysis, specific events in the staff and in the teacher seminars were highly relevant to the conversations in the LIT.

As Miles and Huberman (1989) argued, “Regularities are 'out there' to be discovered, whether or not we are aware of them or can articulate them" (p. 56). When analyzing the interactions from an interpretative layer, it becomes evident that the researcher and Tony built their assumptions on different logics, which become visible in underlying laws and rules. The interaction analysis showed that the researcher recurrently asked if anything had happened since the last meeting according to one specific problem space. The logic behind that might be that when requesting results, there is certain pressure to account for the result. The underlying logic in the researcher's approach might be that if she is recurrently requisitioning any action taken since the last workshop (X as an input), the principal will carry out actions in his school context between the workshops (Y). To ask about what has happened since the last meeting is also one of the several steps in AL. This relation seems to have causal power (cf. Sayer 1992, pp. 2–3) throughout the trajectory of the team since it produced regularities in terms of the reports from actions taken in the school leadership practice.

In Episode 34, it became visible that the project generated changes (according to the principals) in accordance with the intended objects, which is fine. According to the principals, the local project was successful. The statement might be conceptualized as an output (Y) of the activities in the local project (X). However, when grounding the analysis process data over time, the process data reveal tensions and resistance among those involved along the way, which I argue is important to uncover in school improvement work. The role of tensions and contradictions is underestimated in developmental work. Humans face and are driven by multiple contradictory motives across activity systems (Engeström 1987). The present study did not reveal contradictions among the schools, the local educational authority, and the university directly. However the analysis revealed tensions between how Tony, as a leader, and the mathematics teachers thought about the situation. The teachers (according to Tony) claimed that the students were responsible for their low scores, while Tony argued that the teachers were responsible. In other words, tensions arose because of the discrepancies between the principal's and the teachers' interpretations of the low mathematics scores. This finding may not be surprising, since the role of principals has changed from being one of the teachers (of equals) to being a leader with certain rights (Møller 1995), which include promoting and leading professional and organizational learning. As we can see from the data, Tony was struggling to get the mathematics teachers to move forward, which is a typical challenge in change processes. Involving potential resisters in designing and implementing change is, however, one of several strategies to facilitate change (cf. Kotter and Schlesinger 2008). One may argue that the math teachers seemed to act as resisters to the project (according to Tony). The advantage of engaging the resisters is that people feel more committed to making things happen, while the drawback is that an inclusive approach is very time-consuming. After seven months, Tony shared some good news with the team about the math teachers. As many researchers argue (see Barowy and Jouper 2004; Cuban 1988), the process from introducing the initiative to seeing actual changes in practice may be long and complex. Social reality happens in sequences of actions located within both constraining and enabling structures (cf. Abott 1992, p. 428).

When interpreting the situation from an agentive layer (Engeström 2011) based on process data, the focus is on how potential individual and collective agents take intentional transformative actions by inventing and using artifacts to control the action from the outside (Engeström 2011). The argument builds on that of Vygotsky (1978), who argues that human beings are not only controlled by stimuli and things but that they also have a will and a power that enables them to use and control the stimuli and the things with their desires and purposes. In school improvement work, it is reasonable to expect that policymakers, researchers, municipality leaders, school leaders, and teachers will introduce different tools to trigger some sort of improvements in their contexts, such as reports, research, models, narratives, PowerPoint presentations, and state-of-the-art tools. Whether the tools are intentionally introduced and used to mediate an intended result is an empirical question. From the interactions in the LIT, it becomes evident that the researcher structured the conversation in the team using AL methodologies, which may be a way of controlling the conversation “from outside." The researcher also introduced shadowing and mirroring as tools for learning (Jensen and Lund 2014). Tony also attempted to control the conversations in the mathematics team from the “outside" by intervening with the same tool the researcher used (the AL methodology). In other words, several tools were introduced in the project to trigger some sort of school improvement. I argue that including the tools in the unit of analysis is needed when trying to reveal causal relationships between developmental processes in one context that are supposed to mediate developmental processes in another context. Knowledge about the different tools being explicitly introduced to mediate learning (Wertsch 2007) is important knowledge for further projects.

In the age of accountability, it is reasonable that when school leaders and other leaders are leading school improvement work, they feel they are accountable for progress. School leaders are accountable for progress to the higher levels—that is, to the local authority or to the district offices and/or to the national authority—as in the case of the present example. Sinclair (1995) distinguishes between political, managerial, professional, administrative, and personal accountability. When the researcher recurrently asks the principal for the result, she indicates that she is expecting the principal to come up with measures. By requesting result (X), the researcher may expect result (Y). The process data reveal that the principals are recurrently reporting from measures, which may indicate kinds of administrative and professional accountability. After almost 2 years, the process data indicate some results. In developmental work, it may be worth paying attention to any episodes that become conducive to making changes in practices. Process data allow the researcher to look for such episodes.

Schools are not isolated workplaces. They are interwoven in national and international structures of schooling. More than ever, international trends may influence local practices. In the present case, Tony was concerned with “being close to teacher practices.” In education, being close to the practitioners has been a key approach since 2008, when, for example, Robinson et al. (2008) documented through a meta-analysis that school leaders have an indirect influence on student results and wellbeing. School leadership seems to have a significant influence on teaching and on teachers' conditions for facilitating student learning and well-being. The advice Tony received to be close to the teachers reflects recent research (Robinson et al. 2008), which revealed strong average effects for the leadership dimension that involved promoting and participating in teacher learning and development. In other words, it is reasonable to assume that the logic of being close to the teachers did not come from nowhere; it is highly contextualized in educational policies and research. Researchers should be aware of not only the local contexts constituting school improvement work but also the global contexts.

Qualitative data can contribute insights into the processes that achieve results (Engeström 2011), especially when grounded in process data.

Concluding remarks

The present article informs the discussion surrounding the potential use of qualitative data to explore causal relationships qualitatively through an empirical illustration of school leadership development. Specifically, the aim has been to (1) exemplify how researchers are approaching causality, (2) illustrate how causal relationships become visible in the process data of school leadership development, and (3) discuss the potential of using qualitative process data to make causal relationships visible. To achieve this aim, I draw on process data obtained from the LIT. As shown, researchers build on different logics, i.e., the regularity approach, variable approach, and realist approach, when approaching causality (Maxwell 2004a). It is the realist approach that constitutes the context of Engeström's three layers of causation, and CHAT, constituted the theoretical framework of the empirical illustration in the present article. For this purpose, I have shown, with reference to Engeström (2011), how process data from a team might serve as a point of departure to explore causal relationships between school development in the team and school leadership practice where what has been worked on is supposed to be used.

Based on the analyses, I argue that qualitative data have the potential to generate knowledge about important relationships between school leadership development and changes in educational leadership in schools because qualitative studies may include close observations and recordings of unfolding chains of events that show how some events are conducive to changes in school leadership practices (cf. Engeström 2011). The analysis showed that, when interpreting the interactions from excerpts using the interpretative layer, a pattern of interaction in the team became visible. It also became clear that the actors were grounding their approaches in different logics. An analysis of the interactions from a contradictory level revealed evidence of tensions and resistance between the teachers and the leaders in one of the schools. When interpreting the situation from an agentive layer, it became visible that the researcher was structuring the conversation with the help of several tools, while one of the principals was trying to control the conversations in the mathematics team from “outside" by intervening with the same tool as the researcher (the AL methodology). The analysis highlighted the importance of including the interactions between actors and tools in the unit of analysis.

A limitation of the study was that I only had the principal's account of the processes and events in his school. Consequently, his experiences are not backed up with observations from others at the school, which would have strengthened the knowledge claims made about the role of qualitative research as a foundation for the development of educational leadership. In future studies, it would be beneficial to scale up similar studies with more cases. From a theoretical stance, I argue that causation analyses should not be left to quantitative researchers alone. Also, qualitative research can contribute to explaining causal relationships, although not for the same purposes as quantitative research. Qualitative research may explain how processes and events are related, rather than the effect of an input in terms of output. However, qualitative approaches may require that data be collected across different contexts and over time. It may also necessitate an analytical framework that allows for such analyses. CHAT, as a tool that permits analyses of process data, provides a robust theoretical framework option to address this need. In the future, I think it might be exciting to discuss the relationship between correlation and causation in qualitative research.

Change history

18 June 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09427-1

References

Aamodt, P. O., Hybertsen, I. D., Røsdal, T., Stensaker, B., Caspersen, J., & Federici, R. A. (2019). Evaluering av den nasjonale rektorutdanningen 2015–2019 [Evaluation of the National School leadership Education]. NTNU.

Abbott, A. (1992). From causes to events: Notes on narrative positivism. Sociological Methods and Research, 20(4), 428–455.

Barab, S., Hay, S., & Yamagata-Lynch, L. (2001). Constructing networks of action-relevant episodes: An in-situ research methodology. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 10(1), 63–112.

Barab, S. A., & Kirshner, D. (2001). Guest editors’ introduction: Rethinking methodology in the learning sciences. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 10(1), 5–15.

Barowy, W., & Jouper, C. (2004). The complex of school change: Personal and systemic codevelopment. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 11(1), 9–24.

Bates, R. (2006). Culture and leadership in educational administration: A historical study of what was and what might have been. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 38(2), 155–168.

Bates, R. (2013). Educational administration and the management of knowledge: 1980 revisited. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 45(2), 189–200.

Bates, R. J. (1984). Toward a critical practice of educational administration. In T. J. Sergiovanni & J. E. Corbally (Eds.), Leadership and organizational culture: New perspectives on administrative theory and practice (pp. 260–274). Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Bhaskar, R. (1978). On the possibility of social scientific knowledge and the limits of naturalism. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 8(1), 1–28.

Blossing, U., Hagen, A., Nyen, T., & Söderström, Ä. (2010). Kunnskapsløftet ”Fra ord til handling: Sluttrapport fra evalueringen av et statlig program for skoleutvikling [The knowledge promotion”From words to action: Final report from the evaluation of a state program for school development]. FAFO/Karlstads University.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2008). Research methods in education. Routledge-Palmer.

Cuban, L. (1988). A fundamental puzzle of school reform. Phi Delta Kappa, 70(5), 341–344.

Day, D. V. (2011). Leadership development. In A. Bryman, D. L. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 37–50). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Engeström, Y. (2008). Enriching activity theory without shortcuts. Interacting with Computers, 20(2), 256–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2007.07.003.

Engeström, Y. (2011). From design experiments to formative interventions. Theory and Psychology, 21(5), 598–628.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Innovative learning in work teams: Analyzing cycles of knowledge creation in practice. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R. L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 377–404). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2012). Whatever happened to process theories of learning? Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 1(1), 45–56.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Orienta-Konsultit.

Eskola, A. (1999). Laws, logics, and human activity. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R. L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 117–132). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Firestone, W. A., & Riehl, C. (2005). A new agenda for research in educational leadership. New York: Teachers College Press.

Foot, K. A. (2002). Pursuing an evolving object: A case study in object formation and identification. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 9(2), 132–149.

Goodson, I. (1993). The story so far: Personal knowledge and the political [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association 1993, Atlanta, USA.

Greenfield, T. B. (1979). Research in educational administration in the United States and Canada: An overview and critique. Educational Administration, 8(1), 207–245.

Greenfield, T. B., & Ribbins, P. (1993). Greenfield on educational administration, towards a human science. New York: Routledge.

Griffiths, D. E. (1988). Administrative theory. In N. J. Boyan (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational administration (pp. 27–39). New York: Longman.

Hallinger, P. (Ed.). (2003). The emergence of school leadership development in an era of globalization: 1980–2002. In Reshaping the landscape of schoolleadership development: A global perspective (pp. 3–22). Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers.

Heath, C., & Hindmarsh, J. (2002). Analysing interaction: Video, ethnography and situated conduct. In T. May (Ed.), Qualitative research in action (pp. 99–121). London: Sage Publications.

Huber, S. G. (2010). Preparing school leaders: International approaches in leadership development. In S. G. Huber (Ed.), School leadership: International perspectives (pp. 225–251). London: Springer.

Jensen, R. (2020). Professional development of school leadership as boundary work: patterns of initiatives and interactions based on a Norwegian case. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–18.

Jensen, R., & Lund, A. (2014). Horizontal dynamics in an inter-professional school improvement team. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 17(3), 286–303.

Jensen, R., & Møller, J. (2013). School data as mediators in professional development. Journal of Educational Change, 14(1), 95–112.

Jordan, B., & Henderson, A. (1995). Interaction analysis: Foundation and practice. Journal of Learning Sciences, 4(1), 39–103.

Kotter, J. P., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2008). Choosing change strategies. Harvard Business Review, 86(7), 130–139.

Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2008). Linking leadership to student learning: The contributions of leader efficacy. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 496–528.

Leithwood, K. A., & Levin, B. (2005). Assessing school leader and leadership programme effects on pupil learning (Report No. 662). DfES Publications.

Leontév, A. N. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and personality. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Maxwell, J. A. (2004a). Causal explanation, qualitative research, and scientific inquiry in education. Educational Researcher, 33(2), 3–11.

Maxwell, J. A. (2004b). Using qualitative methods for causal explanation. Field methods, 16(3), 243–264.

Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1989). Some procedures for causal analysis of multiple-case data. Internation Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 2(1), 55–68.

Miller, S. I., & Fredericks, M. (1987). The confirmation of hypotheses in qualitative research. Methodika, 1(1), 25–40.

Mulford, B., & Silins, H. (2003). Leadership for organisational learning and improved student outcomes: ”What do we know? Cambridge Journal of Education, 33(2), 175–195.

Møller, J. (2009). School leadership in an age of accountability: Tensions between managerial and professional accountability. Journal of Educational Change, 10(1), 37-46.

Møller, J. (1995). Rektor som pedagogisk leder i grunnskolen: I spenningsfeltet mellom forvaltning, tradisjon og profesjon [The school principal as an educational leader in compulsory school: Tensions between administration, tradition and profession, Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Department of Education, University of Oslo.

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 40.

Sayer, A. (1992). Method in social science: A realist approach (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

Simkins, T., Coldwell, M., Close, P., & Morgan, A. (2009). Outcomes of in-school leadership development work. A study of three NCSL programmes. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 37(1), 29–50.

Sinclair, A. (1995). The chameleon of accountability: Forms and discourses. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(23), 219–237.

Tuomi-Gröhn, T., Engeström, Y., & Young, M. (2003). From transfer to boundary-crossing between school and work as a tool for developing vocational education: An introduction. In Between school and work: New perspectives on transfer and boundary-crossing. Pergamon Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wertsch, J. V. (2007). Mediation. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, & J. M. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Vygotsk (pp. 178–192). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Young, M. D., Mawhinney, H., & Reed, C. J. (2016). Leveraging standards to promote program quality. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 11(1), 12–42.

Young, M. D., & Perrone, F. (2016). How are standards used, by whom, and to what end? Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 11(1), 3–11.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks colleagues in the research group, Curriculum Studies, Leadership, and Educational Governance (CLEG), for helpful comments on drafts of this article.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Unwanted signs €™s were removed throughout the article. Figure 1 is also updated.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jensen, R. Exploring causal relationships qualitatively: An empirical illustration of how causal relationships become visible across episodes and contexts. J Educ Change 23, 179–196 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09415-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09415-5