Abstract

In this paper, I argue for the right node raising (RNR) analysis of coordinated wh-questions in Japanese, according to which verbs or their larger projections are moved rightward across-the-board in the coordinated structures, with the conjoined wh-phrases staying in their original VP domains. I demonstrate that this analysis can properly capture the following properties of this construction: (i) the conjoined wh-phrases retain the in-situ property of wh-phrases in this language; (ii) they behave as if they make a constituent; (iii) they are sensitive to the clause-mate condition. The most crucial theoretical implication of my arguments for the RNR analysis is that the backward ellipsis analysis is inaccessible to coordination in this language. This is further confirmed by the behaviors of what I call backward gapping, which is also amenable to the RNR analysis. I also examine whether this implication holds cross-linguistically, and reach only the tentative conclusion that it might not accord with what has been found out by the bi-clausal analysis of coordinated wh-questions in other languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout this paper, English glosses are often used instead of Japanese words when the structures of Japanese sentences are represented.

In fact, Kasai (2016) observes that the pro posited for the second conjunct that takes the first wh-phrase as its antecedent is actually overtly realized, so that (1a) may have the following variety:

(i)

Dare-ga

sosite nani-o

soitu-ga

Mary-ni

katte-ageta

no?

who-NOM

and what-ACC

the guy-NOM

Mary-DAT

buy-gave

Q

‘Lit. Who1 and what2 the guy1 bought t2 for Mary?’

See Kasai (2016) for his examples of Japanese coordinated wh-questions, most of which involve conjoined wh-phrases appearing in situ. Thus, to the extent that this observation is correct, it invalidates the generalization Lipták (2011) holds:

(i)

If a language does not have wh-fronting, it cannot have coordinated multiple wh-questions. " (Lipták 2011: 179)

Pesetsky (1987) claims that ittai ‘the hell’ functions like the English counterpart in making wh-phrases “aggressively non-D(iscourse) linked” and further that when in-situ wh-phrases are accompanied by ittai, they show island effects. It is generally the case that coordinated wh-questions in Japanese are more natural when ittai is accompanied and that this tendency does not change even in (12a, b). This indicates that Pesetsky’s empirical claim about ittai may not be correct.

These examples become acceptable when the embedded subject John-ga is turned into pro and the latter is bound by the matrix subject. This fact is known as the bound pronoun effect, discussed in detail by Grano and Lasnik (2018), which makes clause-mate effects nullified in various constructions.

NL and COP in the glosses in (22) stand for nominalizer and copular, respectively.

I owe this argument to Koizumi (2000), who argues that such coordination as illustrated below involves ATB verb raising:

(i)

Mary-ga

[John-ni

ringo-o

hutatu to

Bob-ni

banana-o

sanbon]

ageta.

Mary-NOM

John-DAT

apple-ACC

two

and

Bob-DAT

banana-ACC three

gave

‘Mary gave John two apples and Bob three bananas.’

According to this analysis, (i) is derived by raising the verb age ‘give’ from each conjunct into the above T in an ATB fashion. Hence the conjoined phrases marked with brackets make a constituent. Koizumi argues for this analysis by demonstrating that they can be clefted. See the next section for relevant discussion.

In this paper, I do not consider the possibility of the mono-clausal analysis for Japanese coordinated wh-questions, which, as pointed out by a reviewer, would take conjoined wh-phrases to be formed by what Takano (2002) calls oblique movement, that is, adjunction of one wh-phrase to the other. The main reason is that unlike coordinated wh-questions in multiple wh-fronting languages, Japanese coordinated wh-questions do not require that no other phrase intervene between conjoined wh-phrases, as witnessed by the following example (cf. fn. 3):

(i)

Dare-ga

sosite soitu-ga

nani-o

Mary-ni

katte-ageta no?

who-NOM

and the guy-NOM

what-ACC

Mary-DAT

buy-gave Q

‘Lit. Who1 and what2 the guy1 bought t2 for Mary?’

It is not clear how the mono-clausal analysis could explain the acceptability of such a coordinated wh-question.

(34) will be modified in Sect. 5 in such a way that it will not hold when the arguments or modifiers of verbs that undergo ATB movement are contrastively focused.

It might be argued that the rightward ATB movement involved in coordinated wh-questions serves to create a particular informational structure in which V or its larger projection that undergoes this operation functions as background whereas the material left in the coordinated VPs functions as foreground, so that the latter requires some indication of focus. In the case of coordinated wh-questions, the conjoined wh-phrases serve as such. Thus, in (38), dare-ga sosite nani-o ‘who-NOM and what-ACC’ functions as foreground whereas Mary-ni katte-age ‘Mary-DAT buy-give’ functions as background. This characterization is motivated by the fact that if the foreground part of (38) is changed into one that involves non-wh-arguments, then the resulting sentence is unacceptable:

(i)

*John-ga

sosite

hon-o

Mary-ni

katte-ageta.

John-NOM

and

book-ACC

Mary-DAT

buy-gave

‘Lit. John1 and a book2 t1 bought t2 for Mary.’

In this case, no indication of focus is marked in the foreground part. A reviewer kindly provides examples of the relevant coordination in which other ways of focus marking are involved in the foreground part:

(ii)

a.

[Mary-ni

katte-ageta

no]-wa

John-ga

sosite

hon-o

da.

Mary-DAT

buy-gave

NL-TOP

John-NOM

and

book-ACC

COP

‘Lit. It was John1 and a book2 that t1 bought t2 for Mary.’

b.

[John-ga

sosite

hon-o

Mary-ni

katte-ageta]

no

da.

John-NOM

and

book-ACC

Mary-DAT

buy-gave

NL

COP

‘Lit. It was John1 and a book2 that t1 bought t2 for Mary.’

In (iia), the foreground part is put in the pivot position of a cleft. In (iib), sentence (i) is embedded in what Hiraiwa and Ishihara (2002) call the “no da” in-situ focus construction, and this example is acceptable when John-ga sosite and hon-o ‘John-NOM and book-ACC’ serves as the target of focus in this construction.

(42) is somewhat degraded, however, especially so when compared with (35) (one reviewer even rejects it as unacceptable). This might be due to the fact that a non-focused phrase (Mary-ni) is sandwiched between the focused phrases (dare-ga ‘who-NOM and nani-o ‘what-ACC’) in the foreground part (see the previous footnote).

It is predicted under the present analysis that the conjoined VPs in (43) can be clefted. This does not seem to be borne out, however:

(i)

*[Katte-ageta

no]-wa

dare-ga

Mary-ni

sosite

nani-o

na

no?

buy-gave

NL-TOP

who-NOM

Mary-DAT

and

what-ACC

COP

Q

‘Lit. It was who1 for Mary and what2 that t1 bought t2?’

It is natural to attribute the unacceptability of (i) to the fact that wh-phrases are mixed with a non-wh-phrase in the pivot position. In fact, a simple example of clefts that involves such mixing demonstrates that the ban on such mixing is at work:

(ii)

*[Sono

hon-o

katte-ageta

no]-wa

dare-ga

Mary-ni

na

no?

that

book-ACC

buy-gave

NL-TOP

who-NOM

Mary-DAT

COP

Q

‘Lit. It was who1 for Mary that t1 bought that book?’

As a reviewer correctly points out, the present analysis presupposes that coordinated wh-questions in Japanese involve VP coordination, but not coordination of bigger phrases like TP coordination or FP coordination. If FP coordination were possible for this construction, we could not capture the clause-mate effects of this construction properly, since what-ACC in the second conjunct of (49) could reach the Spec-FP without violating the CSC. I have no definite answer to this problem but to speculate that this has something to do with an economy condition on head raising: when VP coordination is involved in the coordinated wh-questions under consideration, raising of an ATB moved V to the above T (in the case of (49), raising of say in the ATB moved V’ to T) is enough to correctly derive this construction, and hence no head raising is necessary in each conjunct. I must leave more detailed consideration of this possibility for future research, however.

To get this reading, we need to change the nominative marker -ga in John-ga into -mo ‘also’. See Abe (2019) for details.

A reviewer raises the question whether the mismatch of NP1 in the first conjunct and the corresponding pronoun pro/sore1 in the second conjunct regarding their internal structures violates the identity condition on ellipsis assumed here. The reviewer raises this question since I argue in what follows that this mismatch does matter for the application of ATB movement under my RNR analysis. Under the particular analysis of Kasai (2016), this mismatch should not matter for the identity condition in question, since otherwise he could not derive a coordinated wh-question such as the following:

(i)

Taroo-wa

nani-o

sosite

dare-no

musume-ni

katte-ageta

no?

Taro-TOP

what-ACC

and

who-GEN

daughter-DAT

buy-gave

Q

‘‘Lit. What and for whose daughter did Taro buy?’

Under Kasai’s analysis, pro must be posited in the first conjunct as a correlate of dare-no musume ‘whose daughter’ in the second conjunct, and the output form of (i) is derived by deleting the relevant VP in the first conjunct after nani-o ‘what-ACC’ is raised out of it, regardless of the mismatch of the two dative phrases in their internal structures. More generally, it has been standardly assumed that such a mismatch regarding internal structure is tolerable in applying ellipsis as long as the relevant two phrases denote the same entity. This is presupposed by Fiengo and May’s (1994) “vehicle change” analysis of such a VP ellipsis construction as the following:

(ii) Mary corrected her mother1’s mistakes before she1 did [VP e].

(Fiengo and May 1994: 222)

If the deleted material of the VP ellipsis site contained her mother, then this would give rise to a Condition C violation due to the fact that she c-commands her mother. In order to solve this problem, Fiengo and May (1994) propose that the deleted material is in fact correct her mistakes with her referring to her mother.

What is moved in the second conjunct must be the whole NP rather than just nani-o ‘what-ACC’ since pro inside that NP can be overtly realized, as shown in (62).

A more thorough investigation will be necessary to answer the question whether RNR actually serves to remedy island violations, just as ellipsis does. I leave this task for future research. See also Section 5 for a similar remedy effect of LBC violation in what I call “backward gapping”.

As a reviewer correctly points out, if the accusative -o is added to dare-no ‘who-GEN’ in (74), the resulting sentence becomes acceptable:

(i)

Taroo-wa

nani-o

sosite

dare-no-o

nusunda

no?

Taro-TOP

what-ACC

and

who-GEN-ACC

stole

Q

‘Lit. What and whose did Taro steal?’

Given that Japanese has pronominal no, meaning ‘one’, dare-no-o is most naturally analyzed as being derived from dare-no-no-o ‘who-GEN-PRO-ACC’ by deleting one of the iterated no occurrences due to haplology. Hence (i) is derived from an underlying structure just like (75) except that dare1-no-proIndf. is modified into dare1-no-no-o, by applying ATB head raising to the shared verb nusun ‘steal’.

I do not intend that my RNR analysis of coordinated wh-questions of Kasai’s (2016) type capture all relevant properties of this construction properly. A reviewer points out that my analysis cannot account for the unacceptability of such a coordinated wh-question as the following (I changed the reviewer’s original example slightly):

(i)

*Taroo-wa

dare-no

sosite

nani-o

dare-ni

ageta

no?

Taro-TOP

who-GEN

and

what-ACC

who-DAT

gave

Q

‘Lit. Whose and what to whom did Taro give?’

This sentence is intended to ask the question of what Taro gave to whom and further whose the thing was that Taro gave. As the reader may verify, my RNR analysis over-generates this unacceptable sentence. At an intuitive level, what is wrong about this sentence seems to be attributed to the fact that even though this question asks about three things, two of them are related to the same entity while the other is related to a different entity. Such an unbalanced way of asking a question seems to cause an anomaly, though I must leave it for future work how this intuition is best characterized in formal terms.

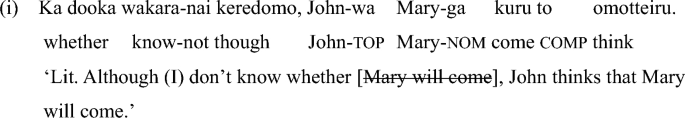

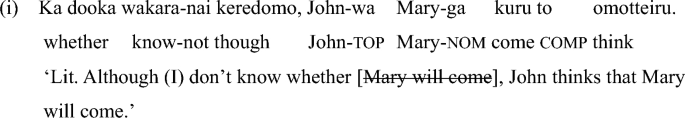

If this reasoning is right, it is predicted that ka dooka ‘whether’ in Japanese should support backward ellipsis if it appears in a subordinated clause, unlike in (77). This prediction is in fact borne out:

Furthermore, this conclusion will require us to reconsider what Giannakidou and Merchant (1998) call “reverse sluicing”, as illustrated in (76). See Park (2006) and Haida and Repp (2011) for the RNR approach to this construction, according to which the shared material of TP in each conjunct is right node raised. However, the following discussion in the text makes it unclear which approach is superior.

A reviewer makes the interesting suggestion that the ban on backward ellipsis in coordination may be a special case of a more general constraint, which will also explain the following facts about VP ellipsis (I owe the following data to the reviewer):

(i)

a.

Because Jeff did [VP e], his children had to go to church last Sunday.

b.

*Jeff did [VP e], because his children had to go to church last Sunday.

c.

*Jeff did [VP e], and his children had to go to church last Sunday.

The reviewer suggests that this constraint “is reminiscent of Langacker’s (1969) Backwards Anaphora Constraint,” which prohibits pronominalization from taking place if the targeted NP precedes and commands its antecedent, accounting for the following contrast:

(ii)

a.

Penelope cursed Peter1 and slandered him1.

b.

*Penelope cursed him1 and slandered Peter1. (Langacker 1969: 162)

If this constraint is extended to apply to ellipsis, the ungrammaticality of (ib, c) is explained by the fact that the VP ellipsis site precedes and commands its antecedent. Likewise, the ban on backward ellipsis in coordination, such as in coordinated wh-questions, will follow from this constraint since the first conjunct precedes and commands the second conjunct.

The following example illustrates a case of backward gapping where modifiers are contrastively focused:

(i)

Kinoo

kooen-de

soiste

kyoo

taiikukan-de

kodomo-tati-ga

asonda.

yesterday

park-in

and

today

gym-in

child-pl.-NOM

played

‘Lit. Yesterday [V’ e] in the park and today in the gym the children played.’

Takano (2002) does not advocate the RNR analysis, though. I leave the examination of his arguments against this analysis for future work.

In the representations in (99), I use traces rather than copies when Bill and Susan have undergone leftward movement just for ease of presentation, since we need to assume under the RNR analysis that unpronounced copies are indistinguishable for applying ATB movement.

Actually, in Abe and Hoshi (1997), we argue that backward gapping does not show clause-mate effects by presenting an example similar to (104) in which the embedded subject is replaced by pro and claiming that the example is acceptable. However, this illustrates what Grano and Lasnik (2018) call the bound pronoun effect, hence not disconfirming the present claim that backward gapping does show clause-mate effects. See fn. 6 for relevant discussion.

Given that the unacceptability of (104) is attributed to the fact that Mary-ni and Susan-ni undergo an illegitimate application of long-distance scrambling, a reviewer reasons that if they undergo further movement across the matrix subjects in order to license their [Focus] features properly, then the resulting sentence should be acceptable. This expectation is not fulfilled, however, as we note with the following example in Abe and Hoshi (1997):

(i)

*Mary-nituite

John-ga

sosite

Susan-nituite

Bill-ga [CP

sono

sensei-ga t

hanasita

Mary-about

John-NOM

and

Susan-about

Bill-NOM

that

teacher-NOM

talked

to]

omotteiru

COMP

think

‘‘Lit. About Mary John [V’ e] and about Susan Bill thinks that that teacher talked t.’

(Abe and Hoshi 1997: 123)

Abe and Hoshi attribute the unacceptability of this example to a violation of a crossing constraint, which prohibits one contrastively focused phrase from moving across the other.

There is a notorious exception to the clause-mate effects of backward gapping: when the NP movement in (103) is string-vacuous, it can even violate island conditions, as shown in the following example, which we cite from Mukai (2003) with a slight modification in Abe and Nakao (2012):

(i)

John-wa

kuma-ni

sosite

Mary-wa

raion-ni

osowareta

hito-o

tasuketa.

John-TOP

bear-by

and

Mary-TOP

lion-by

was.attacked

person-ACC

saved

‘Lit. John [V’ e] by a bear and Mary saved a person who was attacked by a lion.’

(Abe and Nakao 2012: 3)

In order to derive the output form of this example under the RNR analysis, kuma-ni ‘by bear’ in the first conjunct and raion-ni ‘by lion’ in the second must undergo scrambling out of the relative clause island, though the scrambling in question is string-vacuous. See Abe and Nakao (2012) for how the acceptability of such an example as (i) is explained, though their analysis is not compatible with the RNR analysis advocated in the text.

References

Abe, Jun. 2015. The in-situ approach to sluicing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Abe, Jun. 2019. “Licensing ellipsis in a non-agreement language.” Unpublished Ms.

Abe, Jun. 2022. Wh-in situ licensing in questions and sluicing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Abe, Jun, and Hiroto Hoshi. 1997. Gapping and P-stranding. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 6: 101–136.

Abe, Jun, and Chizuru Nakao. 2012. “String-vacuity under Japanese right node raising.” In Proceedings of the Fifth Formal Approaches to Japanese Linguistics, MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 64, ed. Matthew A. Tucker, Anie Thompson, Oliver Northrup and Ryan Bennett, 1–14. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

An, Duk-Ho. 2016. Extra deletion in fragment answers and its implications. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 25: 313–350.

An, Duk-Ho. 2019. On certain adjacency effects in ellipsis contexts. Linguistic Inquiry 50: 337–355.

Chung, Sandra, William A. Ladusaw, and James McCloskey. 1995. Sluicing and logical form. Natural Language Semantics 3: 239–282.

Citko, Barbara, and Martina Gračanin-Yuksek. 2013. Towards a new typology of coordinated wh-questions. Journal of Linguistics 49: 1–32.

Fiengo, Robert, and Robert May. 1994. Indices and identity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Jason Merchant. 1998. Reverse sluicing in English and Greek. The Linguistic Review 15: 233–256.

Gračanin-Yuksek, Martina. 2007. “About sharing.” Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Grano, Thomas, and Howard Lasnik. 2018. How to neutralize a finite clause boundary: Phase theory and the grammar of bound pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 49: 465–499.

Haida, Andreas, and Sophie Repp. 2011. “Mono-clausal question word coordinations across languages.” Proceedings of the 39th Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, edited by Suzi Lima, Kevin Mullin, and Brian Smith, 373–386. Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Hiraiwa, Ken, and Shinichiro Ishihara. 2002. “Missing links: Cleft, sluicing, and “no da” construction in Japanese.” In Proceedings of the 2nd HUMIT Student Conference in Language Research, MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 43, edited by Tania Ionin, Heejeong Ko and Andrew Nevins, 35–54. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

Hoji, Hajime. 1985. “Logical form constraints and configurational structures in Japanese.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington.

Hoji, Hajime. 1998. Null object and sloppy identity in Japanese. Linguistic Inquiry 29: 127–152.

Ishii. Toru. 2014. “On coordinated multiple wh-questions.” In Proceedings of Formal Approaches to Japanese Linguistics 7, edited by Shigeto Kawahara and Mika Igarashi, 89–100. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

Jackendoff, Ray S. 1971. Gapping and related rules. Linguistic Inquiry 2: 21–35.

Johnson, Kyle. 2009. Gapping is not (VP-) ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 289–328.

Kasai, Hironobu. 2016. Coordinated wh-questions in Japanese. Lingua 183: 126–148.

Kazenin, Konstantin. 2002. “On coordination of wh-phrases in Russian.” Ms. Tübingen University and Moscow State University.

Koizumi, Masatoshi. 2000. String vacuous overt verb raising. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 9: 227–285.

Kuno, Susumu. 1978. Japanese: “A characteristic OV language.” In Syntactic typology: Studies in the phenomenology of language, ed. Winfred P. Lehmann, 57–138. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Langacker, Ronald. 1969. On pronominalization and the chain of command. In Modern studies in English: Readings in transformational grammar, ed. David A. Reibel and Sanford A. Schane, 160–186. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lipták, Anikó. 2003. Conjoined questions in Hungarian. In Multiple wh-fronting, ed. Cedric Boeckx and Kleanthes Grohmann, 141–166. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lipták, Anikó. 2011. Strategies for wh-coordination. Linguistic Variation 11 (2): 149–188.

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands, and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mukai, Emi. 2003. “On verbless conjunction in Japanese.” In Proceedings of the thirty-third annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, edited by Makoto Kadowaki and Shigeto Kawahara, 205–223. Charleston, SC: BookSurge.

Park, Myung-Kwan. 2006. The syntax of conjoined wh-elements in English: A preliminary study. Studies in Generative Grammar 16: 555–565.

Pesetsky, David. 1987. “Wh-in-situ: Movement and unselective binding.” In The representation of (in)definiteness, edited by Eric J. Reuland and Alice G.B. ter Meulen, 98–129. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sabbagh, Joseph. 2007. Ordering and linearing rightward movement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25: 349–401.

Saito, Mamoru. 1985. “Some asymmetries in Japanese and their theoretical implications.”Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Saito, Mamoru. 1987. Three notes on syntactic movement in Japanese. In Issues in Japanese Linguistics, ed. Takashi Imai and Mamoru Saito, 301–350. Dordrecht: Foris.

Takano, Yuji. 2002. Surprising constituents. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 11: 243–301.

Takano, Yuji. 2015. Surprising constituents as unlabeled syntactic objects. Nanzan Linguistics 10: 55–73.

Wasow, Thomas. 1972. “Anaphoric relations in English.” Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Takashi Munakata, Myung-Kwan Park and Asako Uchibori for their comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper. I am also deeply grateful to three anonymous reviewers and the editors of JEAL for their meticulous comments and clarifications, which brought great improvements to the final version of this paper. All remaining errors are solely my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Abe, J. The right node raising analysis of coordinated wh-questions in Japanese. J East Asian Linguist 32, 261–301 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-023-09258-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-023-09258-6