Abstract

Building on the existing crosslinguistic research on wh-questions with coordinated wh-pronouns, in this paper we turn to relative clauses and examine the effects of coordination on the grammaticality of relative clauses with multiple relative pronouns. We first discuss a general restriction on relativization, which bans multiple relativization from a single clause. We attribute this restriction to either a syntactic violation (impossible promotion of the head) or a semantic violation (semantic mismatch between the head and the relative clause). Next, we turn to free and headed relatives with coordinated wh-pronouns, showing that they do not display the same amount of crosslinguistic variation as wh-questions with coordinated wh-pronouns. In particular, irrespective of the availability of a mono-clausal structure for wh-questions with coordinated wh-pronouns in a language (which in turn correlates with the availability of multiple wh-fronting), a mono-clausal structure for free relatives with coordinated wh-pronouns is not available. In this respect, free relatives pattern with headed relatives rather than wh-questions. We derive this parallelism from a fundamental difference between relative clauses and questions: the presence of a CP external head in relative clauses, but not in wh-questions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We are not claiming here that there are no differences between wh-questions and free relatives. See Bresnan and Grimshaw (1978) for a careful description of differences such as the behavior of the two with respect to matching effects and agreement.

Different implementations of this idea exist in the literature. Zhang (2007) argues that (8a) is derived by sidewards movement of both wh-phrases to &P, which is later merged as the specifier of the CP that the wh-phrases originated from. Merchant (2008), on the other hand, proposes that each wh-phrase at the left periphery of the clause occupies a distinct specifier of the same C head, and that the conjunction is a spurious coordinator which actually functions as a discourse marker.

We abstract away from variation within the class of multiple wh-fronting languages regarding the landing site for fronted wh-phrases in multiple wh-questions, and use [Spec, CP] throughout the paper. As is well-known since Rudin’s (1988) seminal work, in some MWH-languages, wh-phrases do indeed target [Spec, CP] positions, whereas in others they target lower positions. The parallelism between multiple wh-questions and mono-clausal coordinated wh-questions holds irrespective of whether the wh-phrases in both target [Spec, CP] or some lower position.

Haida and Repp (2011) pursue this parallelism even further, by arguing that the derivation of a CWH literally builds on the derivation of a MWH in that wh-phrases in a CWH first land as multiple specifiers of little \(v\) and subsequently move both upwards (to multiple specifiers of the Focus head) and sidewards (à la Zhang 2007) to form the coordination phrase, which is then inserted as the specifier of the C.

Since English fronts only one wh-phrase overtly, we do not compare the behavior of its CWHs and MWHs.

As pointed out to us by one of the reviewers, the relevant factor is the obligatory versus optional status of the element rather than nominal versus adverbial status of the coordinated wh-phrases. In (17) above, both what and where are obligatorily selected by the verb put. However, coordination of two arguments is also in principle possible, as long as both arguments are optional. Whitman (2004), for example, points out that this is the case with verbs like serve:

-

(i)

Who and what did Kim serve? (Whitman 2004:428)

The verb give behaves similarly in that in certain fairly restricted contexts (typically involving charity giving) it allows only a single argument, as in (ii):

-

(ii)

John gives 20 dollars (whenever he is asked to contribute to a worthy cause).

-

(iii)

John gives to the poor (whenever he is convinced that the recipient IS poor).

To the extent that are (ii)–(iii) are possible, the coordinated variant in (iv), with the paraphrase in (v), also becomes possible (in the same restricted context):

-

(iv)

To whom and what does John usually give?

-

(v)

To whom does John usually give and what does John usually give?

Example (iv), however, is ungrammatical if it describes a single event of John usually giving something to someone. We thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing these two options involving the verb give to our attention and providing the relevant examples.

-

(i)

The structure in (21b) is not the only possible bi-clausal sharing structure for CWHs. Citko (2013), Citko and Gračanin-Yuksek (2013), and Raţiu (2011) also posit a different structure, in which the entire \(v\mathrm{P}\) or TP (containing both wh-phrases underlyingly) is shared between the two conjunct CPs. In Citko and Gračanin-Yuksek (2013), this structure was proposed for Romanian, whose CWHs behave differently from both English, as well as from Polish and Croatian CWHs. Since Romanian is not our focus here, we will not discuss this structure and refer the interested reader to Citko and Gračanin-Yuksek (2013) for relevant data and analysis.

We find the arguments convincing and will not consider the elliptical structure in (21a) as a possible structure for bi-clausal CWHs. We refer the interested reader to Kazenin (2002) for data and discussion.

This does not mean that bi-clausal CWHs in multiple wh-fronting languages are necessarily impossible. For example, the behavior of CWHs with respect to superiority in Polish and Croatian is in principle compatible with both a mono-clausal and a bi-clausal structure. However, since these languages do not show superiority either in non-coordinated or coordinated wh-questions, as shown in (9) through (12), the lack of superiority in CWHs cannot be taken as evidence for a bi-clausal structure the way it is in English.

Van Riemsdijk (2006) notes that adjunct (concessive) FRs can sometimes contain multiple wh-phrases, as in (i). Izvorski (2001) demonstrates the same for Bulgarian.

-

(i)

Whichever CD you buy in whatever store, you always pay too much.

Izvorski (2001) analyzes concessive FRs as bare adjunct CPs. As mentioned in the Introduction and as we will see in what follows, we attribute the ill-formedness of FRs with multiple wh-pronouns to the presence of a CP external head in FRs, which is absent from wh-questions. If concessive FRs also lack an external head, the fact that they allow multiple wh-pronouns is not surprising.

-

(i)

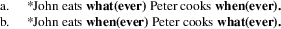

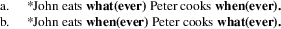

That it is indeed the presence of an extra wh-pronoun, rather than illicit multiple wh-movement that rules out these examples is shown by the fact that they remain ungrammatical even if only one wh-phrase is fronted, as shown in (ia)–(ib).

-

(i)

-

(i)

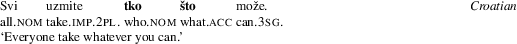

Rudin (2006) argues that Romanian and Bulgarian do have multiple FRs, based on examples like (i).

-

(i)

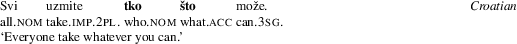

We believe that the construction in (i) is not a typical free relative. For example, in a free relative, the wh-pronoun has to be construed simultaneously with both the matrix and the embedded predicate. Thus, in (ii) what is understood as the object of both take and give.

-

(ii)

I will take what you can give me.

This is not what happens in examples like (i). In the parallel Croatian example in (iii), the matrix clause contains an additional nominative subject svi ‘all’, while the wh-phrase tko ‘who’ is satisfying the selectional requirements of only the embedded verb može ‘can’. Thus, only one of the two wh-phrases is construed with both the matrix and the embedded predicate (Dimova 2014 shows that in Bulgarian, it is always the second wh-phrase). For the time being, we leave the precise analysis of such constructions open. What matters for us is that they are not free relatives. We thank one of the reviewers for a discussion of this construction.

-

(iii)

-

(i)

In (28), we adopt the Comp Account of FRs (Gračanin-Yuksek 2008; Groos and Van Riemsdijk 1981; Grosu 1994, among many others), on which a FR has the structure of a CP which modifies a null head. On the Head-Account (Bresnan and Grimshaw 1978; Citko 2002; Larson 1998), the wh-phrase itself is the promoted head of the FR. On the Head Account, multiple FRs are trivially excluded since it is impossible for a single FR to have two heads.

Again, (29a) remains ungrammatical if only one wh-phrase moves, as in (i), so its ungrammaticality cannot be attributed to illicit multiple wh-fronting. If the second wh-phrase moves covertly (as seems standard to assume), (29a) could be thought of as an LF representation of (i).

-

(i)

*I will talk to whoever John speaks about whomever.

-

(i)

We thank Rajesh Bhatt and Toshiyuki Ogihara for helpful discussion of the semantic issues in this section.

In (32b), the head is generated in its surface position (as opposed to being raised there), in line with the so-called Matching Account. Nothing hinges on this assumption; our insights are also compatible with the alternative account, the so-called Head Promotion Account, on which the head raises from the relative clause internal position. We take this to be a welcome result, given the arguments in the literature that both structures and derivations have to be in principle available (see Sauerland 1998; Husley and Sauerland 2006; Henderson 2007, among others).

We continue to use English merely for illustrative purposes to also represent comparable (also ungrammatical) relative clauses in MWH languages. As noted above, the English examples in (36) and (37) are also excluded as a multiple wh-movement violation. Crucially, however, the status of such examples does not improve if only one wh-phrase moves, as shown in (i)–(ii):

-

(i)

*the student whom \(_{\mathbf{1}}\) Mary introduced t 1 to whom

-

(ii)

*Mary introduced whomever \(_{\mathbf{1}}\) John showed t 1 to whomever.

-

(i)

We thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing to our attention considerations discussed in the following paragraphs. Special thanks go to Rajesh Bhatt for his helpful comments and suggestions.

As pointed out by one of the reviewers, the same problem arises even if the same variable is used in each abstraction step, generating \(\uplambda\mathrm{x}.\uplambda\mathrm{x}.[\dots\mathrm{x}\dots\mathrm{x}\dots]\). The resulting expression would still be of the type that cannot combine with the head of the relative clause, which is of type \(\langle \mathrm{e},\mathrm{t}\rangle\).

We leave the details of the syntactic mechanism that might account for this observation open. We saw above that the structure in (42) is ruled out independently for semantic reasons. We might also rule it out on syntactic grounds by appealing to the Extended Bijective Principle of Wiltschko (1998), given in (i) below.

-

(i)

Extended Bijective Principle

There is a bijective correspondence between an operator-variable chain and a range. (That is, each operator must \(\mathrm{A}'\)-bind exactly one variable, and each variable must be bound by exactly one operator, and for each operator-variable chain there must be exactly one range.) (Wiltschko 1998:169)

On the Matching Account, the range is defined by the internal head (contained within the wh-phrase), deleted under the identity with the external head. Crucially, we assume that the range defined by the internal (deleted) head has to be identical to the range defined by the external head. Thus, in a relative clause with a single relative pronoun, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the number of operator-variable chains and the number of ranges regardless of what analysis of relative clauses one adopts. If, on the other hand, a relative clause contains more than one operator-variable chain (i.e. if it contains multiple relative pronouns), but contains a single range (provided by a single head), we have a mismatch between the number of operator-variable chains (two or more) and the number of ranges (a single one). Such relative clauses are thus excluded by the principle in (i) on both approaches to the derivation of relative clauses.

-

(i)

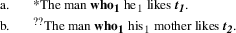

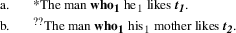

Crucially, we are not claiming that crossover never plays a role in relative clauses. The contrast between the (a) and (b) examples below provides a straightforward illustration of crossover.

-

(i)

-

(i)

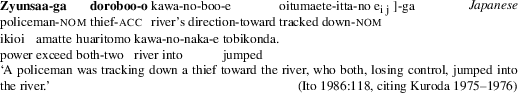

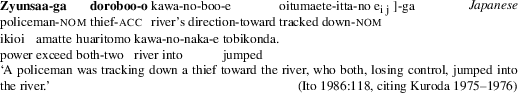

We thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing this prediction to our attention. The same reviewer also points out that Japanese internally headed relatives allow multiple heads (see Ito 1986 for representative discussion), as shown by the example in (i) below with the heads given in bold. While a complete analysis of internally headed relative clauses would take us too far away from the topic of the paper (i.e. the effect of coordination on the grammaticality of relative clauses with multiple relative pronouns), the presence of multiple heads in (i) is not a problem for our analysis, since neither of the two heads is CP external.

-

(i)

The analysis of Japanese and Korean multiply headed internally headed relative clauses in Grosu (2010), refined and improved in Grosu and Landman (2012), is also compatible with our proposal. Grosu proposes that in Japanese and Korean internally headed relatives with a single head, predicate abstraction operates not on the internal head itself, but rather on the variable introduced by a null functional category that he calls Choose Role (ChR), which ranges over a particular thematic role in the denoted event. In cases where there are multiple internal heads, ChR is allowed to range over sums of thematic roles, but there is, crucially, still only a single variable that is available for abstraction, so that the type mismatch resulting from the presence of multiple relative pronouns does not arise.

-

(i)

The possibility of multiple wh-pronouns in (49) was first noted by Rudin (1986) for Bulgarian. These constructions have also been referred to as irrealis free relatives, infinitival free relatives and existential free relatives in the relevant literature, which reflects attempts to assimilate them to free relatives. They differ from free relatives in a number of other respects besides allowing multiple wh-pronouns (e.g. lack of matching effects, incompatibility with ever, restrictions on the use of relative pronouns and complex wh-pronouns, mood restrictions, existential force; see Šimík 2011 for a comprehensive overview). We follow Pesetsky (1982), Rudin (1986), Grosu (1987), Grosu (1994), Izvorski (1998), Pancheva Izvorski (2000), Caponigro (2003), Grosu and Landman (1998) in treating them as bare CPs. On such an account, what distinguishes them from free relatives is the lack of a head. However, we differ from Caponigro (2003) in that we do not treat free relatives as bare CPs.

One of the reviewers also points out that this is compatible with Bhatt’s (2003) analysis of the difference between Hindi correlatives with single versus multiple relative pronouns in that only correlatives with single relative pronouns are externally headed (with the correlative CP adjoined to the demonstrative inside the main clause and moving to the IP-adjoined position), whereas those with multiple relative pronouns are base generated as IP adjuncts.

Coordination of two adjuncts is possible in all three languages, as illustrated below for English.

-

(i)

John eats whenever and wherever Peter cooks.

As we will see in (59), this fact also follows from our analysis.

-

(i)

Caponigro and Pearl (2009) treat FRs headed by wh-phrases like when, where, how as NP complements of a null preposition. One advantage of such an approach is that in (58), where one conjunct is a DP and the other an AdvP, it could avoid a potential violation of the Law of the Coordination of Likes (Williams 1981), assuming that whenever is an NP which moved stranding the null preposition behind. Alternatively, we could assume that the fact that both conjuncts are \(wh\) in character makes them similar enough for the purposes of coordination.

This structure is also forced on the Head Account of free relatives. If the wh-phrase is the head of a free relative, then when a free relative contains two wh-phrases, it follows that it must contain two heads as well.

One of the reviewers points out that categorial mismatches, which is what on our account is responsible for the ill-formedness of (67b), are not always ungrammatical, as shown by the grammatical example in (i), provided by the reviewer.

-

(i)

How(ever) you arrived doesn’t interest me.

We take the mitigating factor here to be the fact that the free relative is in the subject position, and refer the reader to Izvorski (1996) for an in-depth discussion of what allows non-matching subject free relatives. Note that the same free relative however you arrived becomes ungrammatical when it is in an object position of an obligatorily transitive verb:

-

(ii)

*I admire however you arrived.

-

(i)

It also follows from the reasoning above that a CFR is ill-formed if both matrix and embedded predicates are obligatorily transitive, as in (i).

-

(i)

*John devours whatever and whenever Peter prepares.

-

(i)

Another option would be to assume that the coordinated relative clause indeed contains two heads, one of which is overt, while the other is null. We do not pursue this option here, but it should be considered as a logical possibility.

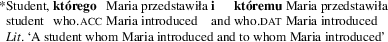

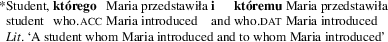

An argument in favor of the structure in (59b) also comes from the ungrammaticality of examples like (ia–b). If (59b) is the only bi-clausal structure that a coordinated headed relative might have, we expect that such a relative will be grammatical only if the relative pronouns are compatible with a single head. In other words, we expect examples like those in (i) below to be ungrammatical, as in fact they are.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Note that on the head promotion analysis, the single overt head originates in each of the relative CPs. We assume that such a configuration is possible because the two CPs are coordinated, so the two CP-internal heads may undergo ATB movement out of the coordinated structure.

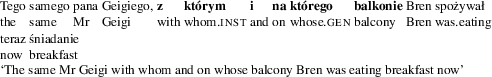

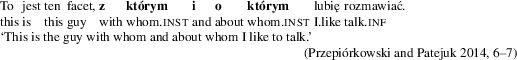

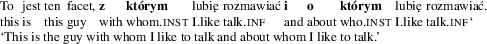

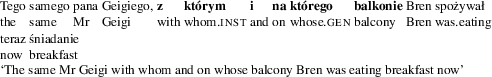

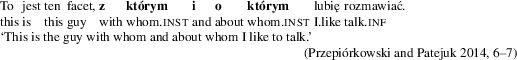

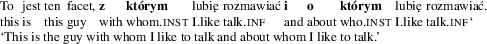

The grammatical examples of relative clauses with multiple relative pronouns discussed by Przepiórkowski and Patejuk (2014), illustrated below, fall into this category.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

Unlike the ungrammatical cases in (74) above, these grammatical examples do allow bi-clausal construals. This is confirmed by the fact that the unreduced counterpart of (76b), the one in which the structure is bi-clausal and does not involve any sharing, remains ungrammatical, as shown in (iii), while the comparable counterpart of (ii), given in (iv) remains grammatical.

-

(iii)

-

(iv)

-

(i)

A similar scenario is also available for coordinated free relatives, as shown in (i).

-

(i)

John will eat whatever Mary cooks and whenever John arrives.

-

(i)

By contrast, in ATB wh-movement cases, the two wh-phrases have to be identical (with the exception of syncretic forms) and only one surfaces overtly (see Citko 2005 and the references therein for a discussion of how these properties of ATB movement follow from a multidominant analysis).

References

Bánréti, Zoltán. 1992. A mellérendelés [Coordination]. In Strukturális magyar nyelvtan I. Mondattan [Structural Hungarian grammar I: syntax], ed. Ferenc Kiefer, 715–797. Budapest: Akad. Kiadó.

Barker, Chris. 2011. Possessives and relational nouns. In Semantics: an international handbook of natural language meaning, Vol. II, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner, 1109–1130. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Bhatt, Rajesh. 2003. Locality in correlatives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 485–541.

Bresnan, Joan, and Jane Grimshaw. 1978. The syntax of free relatives in English. Linguistic Inquiry 9: 331–391.

Browne, Wayles. 1972. Conjoined question words and the limitation on English surface structure. Linguistic Inquiry 3: 223–226.

Caponigro, Ivano. 2003. Free not to ask: on the semantics of free relatives and wh-words cross-linguistically. PhD thesis, University of California, Los Angeles.

Caponigro, Ivano, and Lisa Pearl. 2009. The nominal nature of where, when, and how: evidence from free relatives. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 155–164.

Caponigro, Ivano, Lisa Pearl, Neon Brooks, and David Barner. 2012. Acquiring the meaning of free relative clauses and plural definite descriptions. Journal of Semantics 19: 261–293.

Chaves, Rui P., and Denis Paperno. 2007. On the Russian hybrid coordination construction. In International conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG) 14, ed. Stefan Müller, 46–64. Stanford: Stanford University.

Citko, Barbara. 2002. Anti-reconstruction effects in free relatives: a new argument against the Comp account. Linguistic Inquiry 33: 507–511.

Citko, Barbara. 2005. On the nature of merge: external merge, internal merge, and parallel merge. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 475–497.

Citko, Barbara. 2009. What don’t wh-questions, free relatives, and correlatives have in common? In Correlatives cross-linguistically, ed. Aniko Liptak, 49–80. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Citko, Barbara. 2013. The puzzles of wh-questions with coordinated wh-pronouns. In Challenges to linearization, eds. Theresa Biberauer and Ian Roberts, 295–329. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Citko, Barbara, and Martina Gračanin-Yuksek. 2013. Towards a new typology of coordinated wh-questions. Journal of Linguistics 49: 1–32.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1995. Quantification in correlatives. In Quantification in natural languages, eds. Emmon Bach, Eloise Jelinek, Angelika Kratzer, and Barbara H. Partee, 179–205. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1996. Locality in WH quantification. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Dimova, Elena. 2014. A new look at multiple free relatives: evidence from Bulgarian. Paper presented at 9th annual meeting of the Slavic Linguistics Society, University of Washington, Seattle, September 19–21.

Gawron, Jean Mark. 2001. Universal concessive conditionals and alternative NPs in English. In Logical perspectives on language and information, eds. Cleo Condoravdi and Gerard Renardel de Lavalette, 73–105. Stanford: CSLI.

Gazdar, Gerald. 1980. A cross-categorial semantics for coordination. Linguistics and Philosophy 3: 407–409.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Jason Merchant. 1998. Reverse sluicing in English and Greek. The Linguistic Review 15: 233–256.

Gračanin-Yuksek, Martina. 2007. About sharing. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Gračanin-Yuksek, Martina. 2008. Free relatives in Croatian: arguments for the comp-account. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 275–294.

Groos, Anneke, and Henk Van Riemsdijk. 1981. The matching effects in free relatives: a parameter of core grammar. In Theory of markedness in generative grammar, eds. Adriana Belletti, Luciana Brandi, and Luigi Rizzi, 171–216. Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore.

Grosu, Alexander. 1985. Subcategorization and parallelism. Theoretical Linguistics 12: 231–239.

Grosu, Alexander. 1987. On acceptable violations of parallelism constraints. In Functionalism in linguistics, eds. René Dirven and Vilém Fried, 425–457. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Grosu, Alexander. 1994. Three studies in locality and case. London: Routledge.

Grosu, Alexander. 2003. A unified theory of ‘standard’ and ‘transparent’ free relatives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 247–331.

Grosu, Alexander. 2010. The status of the internally-headed relatives of Japanese/Korean within the typology of definite relatives. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 19: 231–274.

Grosu, Alexander, and Fred Landman. 1998. Strange relatives of the third kind. Natural Language Semantics 6: 125–170.

Grosu, Alexander, and Fred Landman. 2012. A quantificational disclosure approach to Japanese and Korean internally headed relatives. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 21: 159–196.

Haida, Andreas, and Sophie Repp. 2011. Monoclausal question word coordinations across languages. In North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 39, eds. Suzi Lima, Kevin Mullin, and Brian Smith, 359–372. Amherst: GSLA.

Heim, Irene, and Angelica Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Malden and Oxford: Blackwell.

Henderson, Brent. 2007. Matching and raising unified. Lingua 117: 202–220.

Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey K. Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Husley, Sarah, and Uli Sauerland. 2006. Sorting out relative clauses. Natural Language Semantics 14: 111–137.

Ito, Junko. 1986. Head-movement at LF and PF—the syntax of head-internal relatives in Japanese. University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers in Linguistics 11: 109–138.

Izvorski, Roumyana. 1996. (Non-)matching effects in free relatives and pro-drop. In Eastern States Conference on Linguistics (ESCOL) 12, eds. Marek Przezdziecki and Lindsay Whaley, 89–102. Ithaca: CLC.

Izvorski, Roumyana. 1998. Non-indicative wh-complements of existential and possessive predicates. In North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 28, eds. Pius N. Tamanji and Kiyomi Kusumoto, 159–173. Amherst: GSLA.

Izvorski, Roumyana. 2001. Free adjunct free relatives. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 19, eds. Roger Billerey and Brook Lillehaugen, 232–245. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Jacobson, Pauline. 1995. On the quantificational force of English free relatives. In Quantification in natural languages, eds. Emmon Bach, Elfriede Jelinek, Angelika Kratzer, and Barbara Partee, 451–486. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Kallas, Krystyna. 1993. Składnia współczesnych polskich konstrukcji współrzędnych. [The syntax of coordinate constructions of contemporary Polish]. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, Toruń.

Kazenin, Konstantin. 2002. On coordination of wh-phrases in Russian. Ms., Tübingen University and Moscow State University.

Keenan, Edward, and Leonard M. Faltz. 1985. Boolean semantics for natural language. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Kuroda, Sige-Yuki. 1975–1976. Pivot-independent relativization in Japanese (II). Papers in Japanese Linguistics 4: 85–96.

Larson, Richard. 1998. Free relative clauses and missing P’s: reply to Grosu. Ms., Stony Brook University.

Lipták, Anikó. 2011. Strategies of wh-coordination. Linguistic Variation 11: 149–188.

Merchant, Jason. 2008. Spurious coordination in Vlach multiple wh-fronting. Presented at Mid-America Linguistic Conference, University of Kansas, Lawrence, October 26–28.

Pancheva Izvorski, Roumyana. 2000. Free relatives and related matters. PhD thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Paperno, Denis. 2012. Semantics and syntax of non-standard coordination. PhD thesis, University of California Los Angeles.

Partee, Barbara. 1987. Noun phrase interpretation and type-shifting principles. In Studies in discourse representation theory and the theory of generalized quantifiers, eds. Jeroen Groenendijk, Dick de Jongh, and Martin Stokhof, 115–143. Dordrecht: Foris.

Pesetsky, David. 1982. Paths and categories. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Przepiórkowski, Adam, and Agnieszka Patejuk. 2014. Koordynacja leksykalno-semantyczna w systemie współczesnej polszczyzny (na materiale Narodowego Korpusu Języka Polskiego). [Lexical-semantic coordination in contemporary Polish (based on the National Polish Corpus material)]. Język Polski XCIV(2): 104–115.

Raţiu, Dafina. 2011. A multidominance account for conjoined questions in Romanian. In Romance linguistics 2010, ed. Julia Herschensohn, 257–270. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Raţiu, Dafina. 2012. Coordinated vs. matching questions in Romanian. In Conference of the student organization of linguistics in Europe (ConSOLE) XVII, eds. Camelia Constantinescu, Bert Le Bruyn, and Kathrin Linke, 253–268.

Rooryck, Johan. 1994. Generalized transformation and the Wh-Cycle: free relatives as bare WH-CPs. Groeninger Arbeiten zur Germanistischen Linguistik 37: 195–209.

Van Riemsdijk, Henk. 2006. Free relatives. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 338–382. London: Blackwell.

Rudin, Catherine. 1986. Aspects of Bulgarian syntax: complementizers and wh-constructions. Columbus: Slavica.

Rudin, Catherine. 1988. On multiple questions and multiple wh-fronting. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 6: 445–501.

Rudin, Catherine. 2006. Multiple wh relatives in Slavic. In Formal approaches to Slavic linguistics: the Toronto meeting 2006, eds. Richard Compton, Magdalena Goledzinowska, and Ulyana Savchenko, 282–307. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic.

Rudin, Catherine. 2008. Pair-list vs. single pair readings in multiple wh free relatives and correlatives. Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics 30: 257–267.

Rullman, Hotze. 1995. Maximality in the semantics of wh-constructions. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Sauerland, Uli. 1998. The meaning of chains. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Scott, Tatiana. 2012. Whoever doesn’t hop must be superior: the Russian left-periphery and the emergence of superiority. PhD thesis, Stony Brook University.

Šimík, Radek. 2011. Modal existential wh-constructions. PhD thesis, University of Groningen.

Tomaszewicz, Barbara. 2011. Against spurious coordination in multiple wh-questions. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 28, eds. Mary Byram Washburn et al., 186–195. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

De Vries, Mark. 2002. The syntax of relativization. PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam. LOT dissertation series 53.

Whitman, Neal. 2002. Category neutrality: a type-logical investigation. PhD thesis, Ohio State University.

Whitman, Neal. 2004. Semantics and pragmatics of English verbal dependent coordination. Language 80: 403–434.

Williams, Edwin. 1981. Transformationless grammar. Linguistic Inquiry 12: 645–653.

Wiltschko, Martina. 1998. On the syntax and semantics of (Relative) pronouns and determiners. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 2: 143–181.

Winter, Yoad. 1996. A unified semantic treatment of singular NP coordination. Linguistics and Philosophy 19: 337–391.

Zhang, Niina. 2007. Derivations of two paired dependency constructions. Lingua 117: 2134–2158.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers and Marcel Den Dikken, the NLLT editor, for constructive feedback which resulted in significant improvements to the paper. We are also grateful to audiences at the 43rd NELS conference at CUNY Graduate Center, the 87th Annual Meeting of the LSA in Boston, and at a colloquium at Simon Fraser University. We alone remain responsible for any shortcomings and omissions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Citko, B., Gračanin-Yuksek, M. Multiple (coordinated) (free) relatives. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 34, 393–427 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9306-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9306-8