Abstract

In this paper, we argue that the rare-constructions in Japanese are all genuinely passives in the sense that they involve either demotion or removal of an argument in the syntax. For the analysis, we suggest that the rare-constructions are derived with a passive element, Pass(ive), whose essential function is to suppress an argument of its sister predicate. The constant and variable properties across different types of rare-constructions are attributed to the interactions of Pass with the other elements involved in their derivations such as Aff(ect) and T(ense). The paper also discusses the nature of -ni and -niyotte, both of which are often considered to be elements introducing a demoted ‘agent’ argument. We suggest that the different distributions between the two arise because the former is a semantically vacuous argument introducer, whereas the latter is a semantically contentful ‘causer’ introducer. If the analyses presented in this paper are tenable, the paper will constitute a support for the views that passives do not necessarily involve suppression of an ‘external’ argument and that so-called non-canonical passives can also be a true passive to the extent that its derivation involves Pass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It has been claimed that the rare-constructions can be further categorized into some distinct types. The direct rare-constructions, for instance, have been suggested to be distinguished into “-ni” rare-constructions and “-niyotte” rare-constructions (Kuroda 1979, 1992); and the indirect rare-constructions have been suggested to be distinguished into “gapped” rare-constructions and “gapless” rare-constructions (Kubo 1992). In this paper, we focus on the distinction between the direct and indirect rare-constructions, while discussing the other categorizations when necessary.

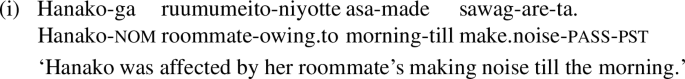

Ishizuka (2010) reports that the indirect rare-construction with an unergative verb is judged unacceptable by native speakers of Japanese with no background in linguistics. The questionnaire surveys that she conducted do not provide any supporting context for the presented examples, and in the out-of-the-blue context, an example like (3b) indeed sounds bad. However, the fact that an example is judged unacceptable without a supporting context does not necessarily mean that it cannot be generated in grammar. It may be just that the example is judged infelicitous because there seems to be no appropriate context in which the example might ever be used: if an example cannot be used in any context that one can imagine, it might as well be just taken to be a bad expression. But an example like (3b) has been generally considered to be grammatical in the literature, and the native speakers of Japanese that we have consulted find it acceptable with a supporting context (e.g., the context for (3b) can be: Taro’s room is right above Hanako’s room, and Taro’s running around in his room makes Hanako distressed because of the loud banging noise that it generates). Ishizuka (2010, 140–142) herself also uses supporting contexts to argue that examples that are initially judged unacceptable can in fact be generated in grammar. Based on these considerations, we maintain with much of the previous literature that the indirect rare-construction can be formed out of an unergative verb.

Note that not all transitive verbs can be passivized in English: e.g., John has a new car vs. *A new car is had by John (Jackendoff 1972; Keenan and Dryer 2007; Williams 2015). It may be assumed that verbs like have, although transitive in English, do not come with agentive Voice, and consequently, cannot undergo passivization (contrary to, e.g., own, which can be passivized as in The house is owned by my sister, and thus can be taken to come with agentive Voice).

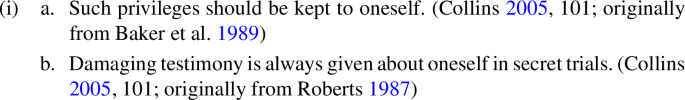

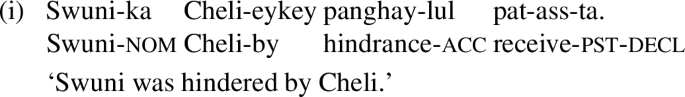

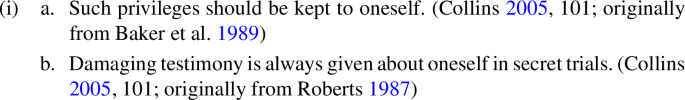

This is not entirely clear in some languages like English, as there are cases in which a reflexive pronoun appears to be licensed by the missing argument of a passive as exemplified below.

However, Alexiadou et al. (2018) point out that examples like (ia–b) are rather impossible across languages, and that the reported cases in English literature all involve modality or negation (which is pointed out to them by Norbert Hornstein). Based on these considerations, we assume with Alexiadou et al. that the missing argument of a passive itself is not a licenser of a reflexive pronoun.

Thanks to Benjamin Bruening for pointing this out.

In principle, then, the VP complement of Voice may be able to check off the [epp] on Pass along the lines of the smuggling approach to the passive (Collins 2005; see Ishizuka 2010 for the analysis of Japanese rare-constructions under the smuggling approach). We will set aside this possibility by assuming that VP as a whole cannot escape from VoiceP because in order to do so, it must first move to the edge of the VoiceP phase (Chomsky 2000), but such movement is not licensed as it is too local (Bošković 1994; Abels 2003; Boeckx 2007). Even if VP could move out of VoiceP in certain environments (e.g., in the ditransitive where there is ApplP intervening between VoiceP and VP), the theme argument inside the moved VP, we assume, would not be able to move to Spec,TP due to the freezing effect (Culicover and Kenneth 1977; Wexler and Culicover 1980), leading to a derivational crash.

A reviewer raises some fundamental questions about the [epp], including the questions of what exactly is the nature of [epp], why the [epp] exists on some heads but not on others, and how it can be learned that certain heads have the [epp] while others don’t. Although these questions are of great importance and should be addressed eventually, we will have to leave to future research the task of looking for answers to these questions. We believe the presence of the [epp] on Pass is worth assuming, even though more fundamental questions regarding the assumption could not be addressed for now, in that, as will be discussed below in the text, the simple assumption provides a principled account of the different behaviors between the direct and the indirect rare-constructions, consequently making it possible to see both the constructions as the passive.

The current approach differs from Miyagawa (1989) in the sense that the former is syntactic whereas the latter is lexicalist in nature, and the former claims that -ni in both the direct and indirect passives is a postposition, whereas the latter claims that -ni in the direct passive is a postposition but -ni in the indirect passive is dative case. See Sect. 2 for evidence which shows that -ni in the indirect passive is a postposition just as -ni in the direct passive is.

The modification has been made so that the generalization can account for not only the absence of accusative case in the transitive-based direct passive but also the presence of accusative case in the transitive-based indirect passive. See the next subsection for discussion of the presence of accusative case in the transitive-based indirect passive.

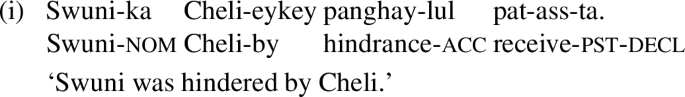

Washio (1993) argues that the indirect passive is interpreted to have an adversative or neutral reading depending on whether the subject is pragmatically related to the object. He offers a conceptual analysis of the interpretive variation of the indirect passive, whose main idea is that a single lexical item like -(r)are may be associated with multiple conceptual structures according to the linguistic and/or pragmatic contexts (cf. Jackendoff 1990). Washio does not provide a syntactic analysis of the (direct or indirect) passive, and his conceptual analysis is compatible with a number of syntactic analyses of the passive, including the one proposed in this paper (e.g., the AFF function that he assumes at the conceptual structure of the indirect passive may as well be encoded into the syntax as Aff in (39)). After all, Washio’s analysis holds at the conceptual level, and how a conceptual representation would be linked to the syntax can be an independent matter (see Washio 1993, 87, endnote 14). Note, however, that the conceptual structures proposed by Washio must not be carried over to the syntax at face value. Washio assumes that the indirect passive in Japanese and the so-called “retained object construction” in Korean (which has the same surface form with the Japanese indirect passive; Yeon 1991, 2005) has the same syntactic structure, and he takes the causative–passive ambiguity to arise in the retained object construction only for conceptual, not syntactic, reasons. Evidence suggests that this is not true; see Yeon (2005), Bosse et al. (2012), Kim (2014), Jo (2020a), among others, for relevant discussion.

Nishigauchi (2014) uses POVP as a cover term that refers to Speech Act Phrase (SAP), Evidential Phrase (EvidP), Epistemological Phrase (EpisP), Evaluative Phrase (EvalP), Benefective Phrase (BenefP), and Deixis Phrase (DeixP). Nishigauchi categorizes the former four as the “sentient class” and the latter two as the “axis class”, whose exact positions in the structure may differ from each other. As the distinction between the two classes of POVPs is tangential to the current discussion, we will use the term POVP in the text while having POVP refer exclusively to the phrases that belong to what Nishigauchi calls the sentient class.

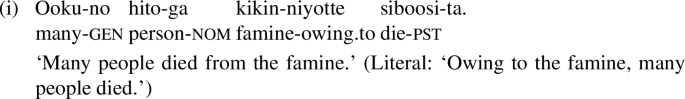

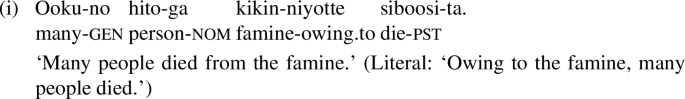

It appears that -niyotte can also appear in the unaccusative as in (i), whose derivation does not involve demotion of any argument.

An example like (i) may further support the view that -niyotte is not the same element as -ni in the passive. Note, however, that when -niyotte is used in the unaccusative, the NP that it introduces needs to be an event-denoting nominal like kikin ‘famine’ rather than an entity-denoting one like Dokutta Heru ‘Doctor Hell’. If the NP introduced by -niyotte is an entity-denoting nominal, the result will not be entirely natural as in ?#Ooku-no hito-ga Dokutta Heru-niyotte siboosi-ta (Intended: ‘Many people died because of Dr. Hell’). This might be due to some pragmatic factors, but unfortunately, we do not have a concrete answer to this issue and so will have to leave it to future research. The issue does not affect the analysis presented in the text, in that when the discussion is limited to the passive, the fact still remains that -niyotte and -ni are different elements in the passive.

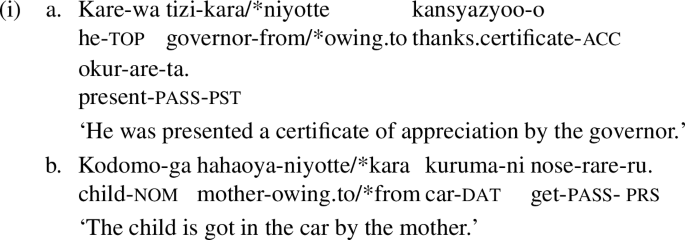

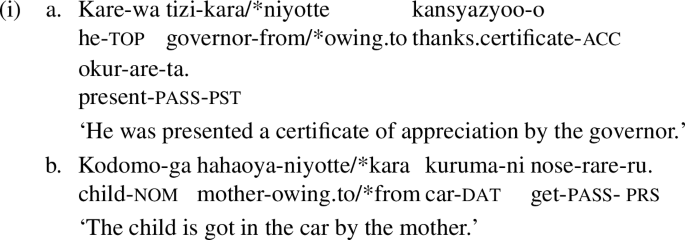

In many languages, a demoted argument in the passive can be introduced by a morphologically complex element like -niyotte (e.g., -eyuyhay in Korean, -tarafından in Turkish). In some of these languages, there is an element that corresponds to -ni in Japanese or by in English in addition to the morphologically complex element (e.g., Korean); whereas, in other languages, there is only a morphologically complex element (e.g., Turkish). In the case of the latter type of languages, it may be said that the passive always involves removal of an argument like the passive in Latvian introduced in (26), but demotion can still be expressed analytically by means of the morphologically complex element that each language employs. The phrases formed with the morphologically complex element may be called “analytic ‘by’-phrase”, as compared to the true ‘by’-phrase like the -ni phrase in Japanese or the by phrase in English. Some literature analyzes -kara ‘from’ on a par with -ni and -niyotte in Japanese passives. In the present view, -ni is a simple ‘by’-phrase that merely introduces an NP that fills in the variable associated with the stem verb (see Sect. 3.1); -niyotte and -kara, are both analytic ‘by’-phrases which contribute something to the semantics of the structure that they attach to. Basically, -niyotte introduces a causer as suggested in the text, while -kara introduces a source as its literal meaning indicates. The difference between the two analytic ‘by’-phrases is demonstrated in (ia–b) (the examples are from Park and Whitman 2003, which are originally from Taramura 1982).

In (ia), -kara is, but -niyotte is not, permitted because the relevant NP is clearly a source, not a causer; and, in (ib) -kara is not, but -niyotte is, permitted because the relevant NP is clearly a causer, not a source. We will not discuss -kara any further in this paper.

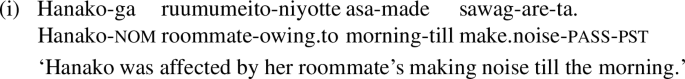

A reviewer points out that even though the unergative-based indirect passive with -niyotte in (56b) is not acceptable, it still sounds better than its unaccusative-based counterpart in (56a), which indicates that there might be a difference between the unergative and the unaccusative regarding the possibility of forming an indirect passive with -niyotte. The reviewer also provides an example of the unergative-based indirect passive, shown in (i), which sounds even better than the example in (56b).

It appears that there are two issues that need to be addressed here: when the -niyotte phrase is used without the -ni phrase, (A) why unergative-based indirect passives (like (56b) and (i)) sound better than unaccusative-based indirect passives (like (56a)); and (B) why some unergative-based indirect passives (like (i)) sound better than other unergative-based indirect passives (like (56b)).

In the text, we have argued that -niyotte introduces a causer into the structure, but the causer is often interpreted to be an agent of the event associated with the stem verb through pragmatic enrichment. Presumably, this is possible because the causer and the agent can be grouped together as the same category of “initiator” in the sense of Ramchand (2008). Now, the argument introduced by -ni in a passive is an agent when the passive is unergative-based. This means that the pragmatic enrichment of the -niyotte phrase may occur in the unergative-based passive, having the -niyotte phrase interpreted as if it were the -ni phrase. Such enrichment might bring about some amelioration effect, by which the -niyotte phrase is perceived to occupy the specifier of Pass, and accordingly, the [epp] on Pass is perceived to be checked off. On the other hand, the argument introduced by -ni in the unaccusative-based passive is a theme, which means that the -niyotte phrase cannot be pragmatically enriched such that the argument that it introduces is interpreted as if it were the -ni phrase (a causer and a theme are too different from each other); accordingly, the amelioration effect cannot take place in the unaccusative-based passive. Hence, the difference between the unergative-based and unaccusative-based indirect passives with -niyotte. The difference between the unergative-based indirect passives in (56b) and (i) may be accounted for from a similar but not the same perspective. The stem verb in (56b) is hasir- ‘run’, and the stem verb in (i) is sawag- ‘make noise’. The sole argument of hasir- is unambiguously an agent, in that the argument is always interpreted as an entity that does the running itself. On the other hand, the sole argument of sawag- is ambiguous such that it can be interpreted as an agent (the argument may make noise by using its own body parts) or, importantly, as a causer (the argument may drop some object on the floor causing the object to make noise). If the sole argument of a verb like sawag- can be interpreted as a causer as such, it may be the case that the -niyotte phrase in the passive with sawag- may be perceived to introduce a demoted argument of that verb, that is, perceived as if it were the -ni phrase. Accordingly, it may be perceived to be merged into the specifier of Pass and perceived to check off the [epp] on Pass. This option is not available for the passive with a verb like hasir-, since its sole argument is unambiguously an agent, not a causer. Hence, the difference between (56b) and (i).

The view presented here is only preliminary, and we will leave a full exploration of this issue to future work.

The example in (71b) is an instance of the stative passive (or “adjectival passive”), not the eventive passive that we have been considering so far; but this does not affect the point being made in the text that the interpretation of the -eykey phrase as a demoted argument is blocked when it can be interpreted as a normally projected argument.

Note in passing that the passive of (71a) can still be formed analytically by using a verb for ‘receive’ as shown below.

The analytic passive of the kind shown in (i) is not available for the verb iyongha- ‘use’ in (69a–b), suggesting that the “pat-passive” might be a strategy for deriving a passive when the markedness constraint in (68) prevents the “toy-passive” from having a passive interpretation.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2003. Successive cyclicity, anti-locality, and adposition stranding. PhD diss., University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Florian Schäfer. 2015. External arguments in transitivity alternations: A layering approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Florian Schäfer. 2018. Passive. In Syntactic structures after 60 years: The impact of the Chomskyan Revolution in Linguistics, ed. Norbert Hornstein, Howard Lasnik, Pritty Patel-Grosz, and Charles Yang, 403–426. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Baker, Mark C. 1988. Incorporation: A theory of grammatical function changing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baker, Marc, Kyle Johnson, and Ian Roberts. 1989. Passive arguments raised. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 219–252.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Roumyana Pancheva. 2006. Implicit arguments. In The Blackwell Companion to syntax, vol. 2, ed. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 558–588. Oxford: Blackwell.

Boeckx, Cedric. 2007. Some notes on bounding. Language Research 43: 35–42.

Bošković, Željko. 1994. D-structure, \(\Theta \)-criterion, and movement into \(\Theta \)-positions. Linguistic Analysis 24 (247): 286.

Bosse, Solveig, Benjamin Bruening, and Masahiro Yamada. 2012. Affected experiencers. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 30: 1185–1230.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2013. By-phrases in passives and nominals. Syntax 16: 1–11.

Bruening, Benjamin, and Thuan Tran. 2015. The nature of the passive, with an analysis of Vietnamese. Lingua 165: 133–172.

Burzio, Luigi. 1986. Italian syntax. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Charnavel, Isabelle. 2020. Logophoricity and locality: A view from French anaphors. Linguistic Inquiry 51: 671–723.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, ed. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 55–89. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chung, Sandra, and William A. Ladusaw. 2004. Restriction and saturation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chung, Sandra, William A. Ladusaw, and James McCloskey. 1995. Sluicing and logical form. Natural Language Semantics 3: 239–282.

Collins, Chris. 2005. A smuggling approach to the passive in English. Syntax 8: 81–120.

Comrie, Bernard. 1977. In defense of spontaneous demotion: The impersonal passive. In Syntax and semantics 8: Grammatical relations, ed. Peter Cole and Jerrold Sadock, 47–48. New York: Academic Press.

Culicover, Peter W., Kenneth Wexler. 1977. Some syntactic implications of a theory of language learnability. In Formal syntax, edited by Peter Culicover, Thomas Wasow, and Adrian Akmajian, 7-0. New York: Academic Press.

Dowty, David. 1991. Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language 67: 547–619.

Dryer, Matthew S. 1994. The discourse function of the Kutenai inverse. In Voice and inversion, ed. Thomas Givon, 65–69. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Fukuda, Shin. 2011. Two types of by-phrase in Japanese passive. In Japanese/Korean Linguistics 18, ed. William McClure and Marcel den Dikken, 253–265. Stanford: CSLI.

Fukui, Naoki. 1986. A theory of category projection and its applications. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Goro, Takuya. 2006. A minimalist analysis of Japanese passives. In Minimalist Essays, ed. Cedric Boeckx, 232–248. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hoshi, Hiroto. 1999. Passives. In The handbook of Japanese linguistics, ed. Natsuko Tsujimura, 35–191. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Inoue, Kazuko. 1976. Henkei Bunpooto Nihongo [Transformational Grammar and Japanese]. Tokyo: Taishukan.

Ishizuka, Tomoko. 2010. Toward a unified analysis of passives in Japanese: A cartographic minimalist approach. PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Iwasaki, Shoichi. 2018. Passives. In The Cambridge handbook of Japanese linguistics, ed. Yoko Hasegawa, 530–556. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1972. Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1990. Semantic structures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jo, Jinwoo. 2020a. On the causative–passive correlation in Korean. Studies in generative grammar 30: 517–545.

Jo, Jinwoo. 2020b. Selecting argument structure: A purely syntactic approach to natural reflexives, causatives, and passives. PhD diss., University of Delaware.

Keenan, Edward L., and Matthew S. Dryer. 2007. Passive in the world’s languages. In Language typology and syntactic description, second edition, Volume I: clause structure, ed. Timothy Shopen, 325–361. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kim, Lan. 2014. The Syntax of Lexical Decomposition of predicates: Ways of encoding events and multidimentional meanings. PhD diss., University of Delaware.

Kinsui, Satoshi. 1997. The influence of translation on the historical development of the Japanese passive construction. Journal of Pragmatics 28: 759–779.

Kiparsky, Paul. 2013. Towards a null theory of the passive. Lingua 125: 7–13.

Kitagawa, Yoshihisa. 2018. Floating quantifiers in Japanese passives and beyond. Journal of Japanese Linguistics 34: 245–279.

Kitagawa, Yoshihisa, Kuroda, Sige-Yuki. 1992. Passive in Japanese. http://www.indiana.edu/~ykling/Resource%20files/Publication%20pdfs/KitagawaKuroda(1992)JPP.pdf. Accessed June 29 2019.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, ed. John Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 109–137. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kubo, Miori. 1992. Japanese passives. In: Institute of language and culture studies working papers 23. Sapporo: Hokkaido University.

Kuno, Susumu. 1973. The structure of the Japanese language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kuroda, Sige-Yuki. 1979. On Japanese passives. In Explorations in linguistics: Papers in honor of Kazuko Inoue, edited by George Dudley Bedell, Eichi Kobayashi, and Masatake Muraki, 305–347. Kenkyusha: Tokyo.

Kuroda, Sige-Yuki. 1992. On Japanese passives. In Japanese syntax and semantics: Collected papers, ed. Sige-Yuki. Kuroda, 21–183. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Lazdina, Tereza Budina. 1966. Teach yourself Latvian. London: English Universities Press.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2012. Subjects in Acehnese and the nature of the passive. Language 88: 495–525.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2014. Voice and v: Lessons from Acehnese. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Legate, Julie Anne, Faruk Akkuş, Milena Šereikaitė, and Don Ringe. 2020. On passives of passives. Language 96: 771–818.

Marantz, Alec. 1984. On the nature of grammatical relations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McCawley, Noriko Akatsuka. 1972. A study of Japanese reflexivization. PhD diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Miyagawa, Shigeru. 1989. Structure and case marking in Japanese. New York: Academic Press.

Murasugi, Keiko, and Koji Sugisaki. 2008. The acquisition of Japanese syntax. In The Oxford handbook of Japanese linguistics, ed. Shigeru Miyagawa, 250–286. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Murphy, Andrew. 2014. Stacked passives in Turkish. In Topics at InfL (Linguistische Arbeits Berichte 92), edited by Anke Assmann, Sebastian Bank, Doreen Georgi, Timo Klein, Philipp Weisser, and Eva Zimmermann, 263–304. Universität Leipzig.

Nishigauchi, Taisuke. 2014. Reflexive binding: Awareness and empathy from a syntactic point of view. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 23: 157–206.

Oshima, David Y. 2006. Adversity and Korean/Japanese passives: Constructional analogy. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 15: 137–166.

Park, Sang Doh, and John Whitman. 2003. Direct movement passives in Korean and Japanese. In Japanese/Korean Linguistics 12, ed. William McClure, 307–321. Stanford: CSLI.

Perlmutter, David M., and Paul M. Postal. 1984. The 1—Advancement exclusiveness law. In Studies in Relational Grammar 2, ed. David M. Perlmutter and Carol G. Rosen, 25–81. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2008. Introducing arguments. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ramchand, Gillian. 2008. Verb meaning and the Lexicon: A first-phase syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, Ian. 1987. The representation of implicit and dethematized subjects. Dordrecht: Foris.

Sadakane, Kumi, and Masatoshi Koizumi. 1995. On the nature of the “dative’’ particle \(ni\) in Japanese. Linguistics 33: 5–13.

Schäfer, Florian. 2008. The syntax of (anti-)causatives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Shibatani, Masayoshi. 1978. Nihongo no bunseki [An analysis of Japanese]. Tokyo: Taishukan.

Shibatani, Masayoshi. 1985. Passives and related constructions: A prototype analysis. Language 61: 821–848.

Shibatani, Masayoshi. 1994. An integrational approach to possessor raising, ethical datives, and adversative passives. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, edited by Susanne Gahl, Andy Dolbey, and Christopher Johnson, 461–486. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Speas, Margaret. 2004. Evidentiality, logophoricity and the syntactic representation of pragmatic features. Lingua 114: 255–276.

Takezawa, Koichi. 1987. A configurational approach to case-marking in Japanese. PhD diss., University of Washington.

Taramura, Hideo. 1982. Nihongono sintakusu I [Japanese syntax I]. Tokyo: Kurosio.

Tomioka, Satoshi, and Lan Kim. 2017. The give-type benefactive constructions in Korean and Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 26: 233–257.

Washio, Ryuichi. 1993. When causatives mean passive: A cross-linguistic perspective. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 2: 45.

Wexler, Kenneth, and Peter W. Culicover. 1980. Formal principles of language acquisition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Williams, Alexander. 2015. Arguments in syntax and semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yeon, Jaehoon. 1991. The Korean causative–passive correlation revisited. Language Research 27: 337–358.

Yeon, Jaehoon. 2005. Causative–passive correlations and retained-object passive constructions. In Studies in Korean Morpho-syntax: A functional–typological perspective, ed. Jaehoon Yeon, 163–183. London: Saffron.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the comments and suggestions of Benjamin Bruening, Satoshi Tomioka, Darrell Larsen, Hee-Don Ahn, Keita Ishii, and the audience at LSA 94. We are also thankful for the helpful comments of the anonymous reviewers for the Journal of East Asian Linguistics. All remaining shortcomings are our responsibility. An earlier version of the paper has been published in the PhD dissertation of one of the authors (Jo 2020b).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jo, J., Seo, Y.A. Japanese rare-constructions and the nature of the passive. J East Asian Linguist 32, 91–132 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-023-09253-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-023-09253-x