Abstract

Gothic preverb compounds illustrate several interesting characteristics, including multiple preverb stacking, idiomatisation, tmesis (i.e., separation by clitics), and P-copying (i.e., multiple pronunciation of the preverb). This paper is a close examination of the morphosyntax of these compounds, highlighting novel empirical generalisations about the Gothic language with key theoretical implications for our understanding of Germanic complex verbs and the alternations they participate in. In particular, this paper proposes a structural distinction between preverb compounds which are obligatorily semantically transparent and those which are optionally idiomatic. In arguing that transparent compounds involve the mechanism of preposition incorporation and m-merger, paralleling recent accounts of clitic doubling, while idiomatic compounds involve a thematic high applicative projection, this paper captures nuanced differences in these compounds’ case assignment and argument licensing behaviour. These structural differences will be shown to derive these two compound types’ constrained interaction with the aforementioned phenomena of stacking, tmesis, and copying. In addition, this paper compares Gothic complex verbs to their cross-linguistic correlates within and beyond Germanic, whilst also providing a diachronic pathway for the development of (multiple) preverb compounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The extinct East Germanic language Gothic has a class of invariant prefixes which attach to verbs, known in the Indo-Europeanist tradition as preverbs. While most preverbs are adverbial or adpositional in origin and attested as independent words, some exist only as inseparable particles. A selection of Gothic preverbs is given in Table 1 (adapted from Bucsko 2011; Miller 2019), alongside their meaning, functional status when not preverbal, and the case assigned by their prepositional equivalents.

The topic of preverbs and their origins within Indo-European is well-discussed (Kuryłowicz 1964; Booij and van Kemenade 2003; Dunkel 2014; i.a.), focusing on their reconstruction and categorial status in the proto-language or their distribution within individual daughter languages. Recent research has turned to the phenomenon of multiple preverbation within Classical Sanskrit (Papke 2010), Homeric Greek (Imbert 2008; Zanchi 2014), and Old Irish (McCone 1997; Rossiter 2004). However, little work has been conducted on this topic within Germanic due to the dearth of preverb-stacking data in the Northern and Western branches, a gap this paper seeks to fill. In addition, previous works have been primarily situated in the realm of historical, descriptive, or cognitive linguistics (Rice 1932; West 1982); this paper presents a formal account within Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1994) aimed at not only modelling but also deriving the distribution of Gothic preverbs and their interaction with other morphosyntactic phenomena within the language.

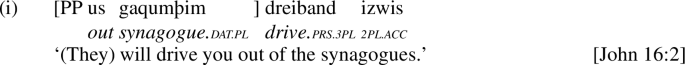

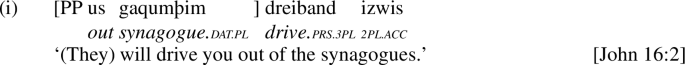

Semantically, these preverbs often append transparently spatial meaning to the verb stem (1), but may also produce idiomatic interpretations (2). Several preverbs can attach to a single verb stem, producing multiply prefixed compounds (3). This article argues that the preverb compounds (PVCs) in (1) and (2) demonstrate different empirical characteristics and involve distinct morpho-syntactic derivations, and that multiple preverb compounds (MPCs) as in (3) are a hybrid of these two structures.Footnote 1

The remainder of Sect. 1 provides an overview of the Gothic language, its corpora, and its relationship to Greek. Sections 2, 3, and 4 elaborate on and provide evidence for the structures of semantically transparent (1), idiomatic (2), and multiple preverb compounds (3) respectively. These sections demonstrate how the distribution of phenomena such as idiomaticity, P-Copying, valency and case alternations, and tmesis are constrained with respect to PVC/MPC compounds by the mechanisms of P-Incorporation, m-merger, Multiple Copy Spell-Out, and applicativisation. This paper derives these complex interactions by arguing that obligatorily semantically-transparent PVCs (1) involve incorporation of a preverb which originates as a categorised preposition P, optionally idiomatic PVCs (2) involve the preverb serving as the Appl head of a high applicative projection, and MPCs (3) involve a combination of these two structures. Finally, Sect. 5 presents a possibly cyclic diachronic pathway for the development of these PVCs and MPCs while Sect. 6 concludes.

1.1 Gothic data: sources and independence

The majority of attested Gothic comes from Wulfila’s 4th Century AD translation of the Bible,Footnote 2 the primary textual reference for which is Streitberg (1919) with an addendum compiled by Piergiuseppe Scardigli in the 7th edition (2000) including texts discovered post-1919. This article basis its conclusions on this biblical data and the Skeireins commentary to the exclusion of non-biblical fragments.Footnote 3

There are two reasons for delimiting the data under discussion to the Bible. Firstly, many of the non-biblical texts (e.g., the calendar and Naples/Arezzo deeds) are too short, fragmentary, or repetitive to allow for meaningful generalisations to be drawn. Secondly, while current scholarly opinion favours the Gothic Bible as the work of several translators potentially overseen by Wulfila (Metlen 1932; Friedrichsen 1961; Ratkus 2018; Miller 2019),Footnote 4 these texts retain a degree of uniformity in genre and purpose that better facilitate analysis.

Yet the nature of the Gothic Bible as a translation from Greek means that any morphosyntactic work begs the question of independence—to what extent is the phenomenon we are observing a genuine Gothic construction as opposed to a calque from Greek? The dearth of autochthonous texts has been claimed to undermine the utility of Gothic for any serious linguistic analysis (Goetting 2007); however, this paper argues that PVCs and MPCs offer key insights into the morphosyntactic structure of compounds and their derivation.

The clearest evidence that these preverbs instantiate a true Germanic inheritance comes from their parallel attestation in both the Western (Old High German, Old English) and Northern branches (Old Norse, Old Swedish) (Hopper 1975, 40–43). Indeed, preverbs and PVCs are robustly attested throughout Indo-European, well beyond Greek.Footnote 5 In addition, while it remains indeterminate which Greek text(s) Wulfila based the translation on,Footnote 6 close comparison with the Koine Greek version highlights several mismatches that disavow a mechanical one-to-one translation.Footnote 7 West (1982, 139), drawing from Rice (1932), illustrates the percentage frequencies for how often a given Gothic preverb translates a simplex verb in Greek. These rates of ‘non-correspondence’ range from 14.3% (faur-) up to 70.2% (du-); of the 14 preverbs studied by Rice , an average of 44.85% of Gothic PVCs translate Greek verbs with no corresponding preverb. Appendix A illustrates numerous ways in which the Gothic and Greek texts diverge, drawing from both lexical-translational and syntactico-functional differences to show that the Gothic data attests an independent system of preverbs and PVCs which this paper investigates.

1.2 Preverb compound structure(s)

A long-running debate in the Germanic literature has centred on whether so-called prefix and particle verbs share a unified structure (Booij 1990; McIntyre 2002; Ramchand and Svenonius 2002, a.o.) or involve distinct syntactic derivations (Wurmbrand 1998, 2000; Biskup et al. 2011, a.o.). Whilst earlier work has primarily focused on German, Dutch, and English, this paper proposes that Gothic PVCs—the forebears of these complex verbs—add novel evidence to this debate. Recall the interpretively-distinct semantically transparent and idiomatic PVCs as introduced in (1) and (2). This paper argues that these surface-similar non-idiomatic and idiomatic PVCs introduce their preverb to the verbal complex through different syntactic mechanisms, resulting in distinct morphosyntactic structures and empirical characteristics.

I propose that obligatorily non-idiomatic (i.e., semantically transparent) PVCs involve P-Incorporation of a categorised preposition into the verbal complex via the process of m-merger (Matushansky 2006; Harizanov 2014) as in (4a), while optionally idiomatic PVCs involve base-generation of an acategorial preverbal root as the head of a High Applicative projection (Pylkkänen 2008) into which the verb head-moves (4b). I will argue on the basis of locality restrictions on idiomatic licensing that the structure in (4a) precludes all non-compositional meaning, while that in (4b) allows but does not obligate idiomatic interpretation.

The structures in (4) differ primarily in i) the presence of a movement chain involving the preverbal element,Footnote 8 and ii) the categorial status of the preverbal element. I argue that these parameters capture a wide range of syntactic, semantic, and phonological differences in the behaviour of the two types of PVCs with respect to phenomena such as P-Copying, tmesis, case-assignment, valency alternations, and idiomaticity. In showing a mix of these characteristics, Multiple Preverb Compounds (MPCs) will be argued to involve a hybrid structure as in (5), where an optionally idiomatic PVC takes a PP adjunct which raises and undergoes m-merger, appending an additional, outermost non-idiomatic preverb to the verbal complex.

This paper focuses first on the structure of non-idiomatic PVCs and evidence in favour of an analysis involving P-Incorporation and m-merger.

2 The structure of obligatorily non-idiomatic PVCs

Where Harbert (1978) and Eythórsson (1995) have intuited that Gothic PVCs involve a form of P-Incorporation (Baker 1985), I argue that this is only true of strictly non-idiomatic PVCs. There have been a variety of mechanisms proposed for implementing incorporation in more contemporary frameworks building off of Baker (1985); one key parallel comes from certain formal approaches to clitic doubling cross-linguistically (Nevins 2011; Harizanov 2014; Kramer 2014), which has been argued to comprise two main steps—one of syntactic movement and one of morphological complex head formation via the operation of m-merger.

As proposed by Matushansky (2006), morphological merger (or m-merger) is a post-syntactic operation which changes structures of type (6a) into that of (6b); a head which is either first-merged or moved (via an Agree relation) into the specifier of another projection can be restructured into an adjunct of the head of that latter projection, producing a complex head.

While Matushansky’s (2006) original conception of m-merger only admits rebracketing of non-branching maximal projections (i.e., X), subsequent approaches in Harizanov (2014) and Kramer (2014) have proposed a reformulation of m-merger which allows it to apply to branching specifiers (i.e., XP), such that complex head formation may alternatively be fed by phrasal movement with subsequent reduction to just a head. In particular, Harizanov (2014) argues that m-merger adjoins only labels—adopting Bare Phrase Structure (Chomsky 1995), the XP vs. X distinction is irrelevant, such that movement of a XP would be akin to movement of a X in allowing for subsequent adjunction of just the head of the moved phrase. Alternatively, Kramer (2014) posits that the branching specifier is structurally reduced to just its head, which is then adjoined; both approaches produce the same output as in (6b). In this vein, I assume that m-merger may be fed by phrasal movement as well as head movement.

I propose that phrasal movement of a PP feeds the formation of obligatorily non-idiomatic PVCs in Gothic,Footnote 9 where the preverb originates as a preposition which incorporates into the verb. The proposed analysis of non-idiomatic Gothic PVCs is illustrated in (7). In (7a), the preverb begins the derivation as an adpositional P head which raises into Spec, vP as part of a PP.Footnote 10 This PP undergoes m-merger (7b), adjoining the head of the PP to the head of vP and producing a complex v\(^{\circ }\) head (which itself has been head-raised into by V).Footnote 11 This head is Spelled-Out as the PVC, with the preverb forming a complex morphological word with the verbal base. Assuming the Copy Theory of Movement (Chomsky 1995) and canonical Chain Reduction in respect of the Linear Correspondence Axiom (Kayne 1994; Nunes 2004),Footnote 12 deletion of the lower P head produces the following surface string: Preverb-Verb (Direct Object) Oblique Object.

Key to this analysis is that the preverb begins the derivation as a preposition. Within the framework of Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1994), I assume that lexical roots are category-neutral and must combine with a categorising head like v or n prior to Spell-Out (Marantz 2001). In (7), the P head instantiating the preverb should be understood as a root (e.g., \(\sqrt{{\textrm{ana}}}\) + p), following work by Acedo Matellán (2010); Haselbach and Pitteroff (2015); and Wood and Marantz (2017). This characterisation will prove essential when we compare these non-idiomatic PVCs to their idiomatic counterparts in Sect. 3, which are argued to instead employ the bare, uncategorised root—in particular, this categorial distinction will be shown to capture differences in the case assignment properties and possible argument structure alternations for each PVC type.

There are two main aspects of the incorporation analysis which must be substantiated: first, the existence of a movement chain involving the P(P) and feeding m-merger; second, that the preverb head originates as a prepositional element. These are discussed in turn.

2.1 Evidence for P-incorporation as movement: P-Copying and tmesis

We must first justify the existence of the lower P head copy prior to incorporation and deletion, especially given its non-overtness. What evidence is there that the preverb is not first-merged in a prefixal position? Strong support in favour of a movement-based approach and the existence of a covert copy comes from how this copy need not be deleted at all. The phenomenon here called ‘P-Copying’ involves the pleonastic repetition of a given preposition in both its preverbal position and as the head of a prepositional phrase:

P-Copying is common in the Gothic Bible, with approximately 140 attestations spread across 9 preverbs (Appendix B.1).Footnote 13 Of these, us ‘out’ shows copying most frequently with 66 occurrences, followed by af ‘from’ with 30 occurrences. For instance, of the 10 attestations of af-niman ‘take away’ involving source DPs, 9 are introduced by an extra af.Footnote 14 P-Copying is also found elsewhere in Indo-European, as exemplified in Latin and Greek:

Although Goetting (2007) argues that Gothic P-Copying arises from mechanical translation of the Greek, there are numerous examples of P-Copying in Gothic where the Greek and Latin parallels have no preverb:

In addition, P-Copying is attested in West Germanic languages such as Old High German (11), suggesting that the grammatical availability of P-Copying is a Germanic inheritance even if its actuation was influenced by translation.Footnote 15

I argue that P-Copying transparently reveals that non-idiomatic PVCs involve two copies in a movement chain. Notably, P-Copying never occurs with inseparable particles like fra-, ga-, and dis-. This observation falls out straightforwardly from a P-Incorporation account—as these preverbs do not exist as independent adpositions capable of projecting PPs, they cannot undergo the necessary movement required to produce copies.Footnote 16

Canonical movement is such that Chain Reduction deletes of all but one of the copies in a chain: the logical follow-up question is thus why and how this process ‘fails’, giving rise to Multiple Copy Spell-Out. While there are numerous proposals attempting to explain similar phenomena like V(P)-doubling in Chinese (Cheng 2007; Cheng and Vicente 2013; Lee 2020) and Hebrew (Landau 2006), wh-copying in Germanic (Felser 2004; Nunes 2004), and pronoun-doubling in Dinka Bor (van Urk 2018), I believe that clitic doubling most closely parallels P-Copying.Footnote 17

Clitic doubling, in which a single nominal argument is expressed by both a pronominal clitic and a full N/DP in its original base position, has been frequently argued to involve m-merger (Nevins 2011; Harizanov 2014; Kramer 2014). Harizanov (2014) proposes that clitic doubling in Bulgarian involves a nominal phrase in argument position which first raises to Spec, vP before undergoing head adjunction, resulting in cliticisation of the (pro)nominal D head onto v. Crucially, this restructuring renders the head of the movement chain distinct from its tail, allowing for Multiple Copy Spell-Out. I argue that the same analysis can be applied to P-Copying as fed by P-Incorporation, save that the raised element is a P(P) whose head adjoins to v instead of a D(P).Footnote 18 The following subsection discusses how and when this restructuring takes place.

2.1.1 Multiple Copy Spell-Out

One proposed analysis of Multiple Copy Spell-Out is via the process of Morphological Fusion (Nunes 1999, 2004; Kandybowicz 2007).

In their accounts of doubling in German and Nupe respectively, Nunes (2004) and Kandybowicz (2007) induce fusion with null elements (a C and Focus head). Extending this analysis to Gothic, we can posit that fusion optionally occurs between the incorporated preverb and the V-v complex it adjoins to, resulting in a terminal which is morphologically opaque at PF. The P-Copying in (8a) would thus have the following structures before and after fusion, with # indicating prosodic word boundaries:

However, this account is too strong. Fusion is proposed to occur prior to Vocabulary Insertion (VI). This would require that the afniman inserted into the fused terminal node be listed in the Lexicon as a separate Vocabulary Item from either of its constituents af or niman, predicting that the PVC should not inherit any morphosyntactic behaviour from niman. This is not true: niman is a Class IV strong verb, with idiosyncratic vowel ablaut: infinitive niman \(\sim \) 3sg past tense nam \(\sim \) past participle numans. All PVCs deriving from niman are also Class IV, and never take weak verb inflection; e.g., 3sg past af-nam ‘took away’, not **af-nimda. In fact, all PVCs track the inflectional class of and inherit irregularities from their simplex verb base. Thus, it is clear that the preverb + verb complex retains some morphosyntactic decompositionality prior to Vocabulary Insertion.

Instead of Fusion operating on the output of m-merger, we can simply posit that m-merger itself renders the complex P-v head invisible to the linearisation algorithm. In line with intuitions in Chomsky (1995, 337) and Nunes (2004, 168, fn. 33) that the Linear Correspondence Axiom does not apply ‘word-internally’, I follow Harizanov (2014) in assuming that the internal structure of the derived v\(^{\circ }\) head is opaque to Chain Reduction and that the higher copy of P is not visible for copy deletion, resulting in Multiple Copy Spell-Out. Crucially, ordering m-merger before Vocabulary Insertion would not require a separate non-decomposable listing of afniman in the Lexicon, since m-merger, unlike Fusion, allows for phonological unification of the preverb + verb complex without manipulating the number of terminals available for VI in the PVC’s underlying morphosyntactic structure.

To capture the optionality of P-Copying, I tentatively propose that there is variability in the relative ordering of operations which take place after raising of the PP—namely, between Chain Reduction and reduction of PP \(\rightarrow \) P. As defined by Kandybowicz (2007, 141), two copies are non-distinct if they i) constitute links of a movement chain, and ii) are ‘morphosyntactically isomorphic’—meaning that both copies must be consistent as to whether they are heads or phrases (cf. also Kramer 2014, 621, fn. 38). If Chain Reduction occurs after the PP has moved to Spec, vP but before it reduces to P, the head and tail of the chain remain morphosyntactically isomorphic and visible for deletion. While this should result in deletion of the entire lower PP, a recoverability condition may restrict this to only partial deletion of just the lower P head and not its complement, since reduction of the higher PP copy to just its head would result in the oblique DP failing to be pronounced at either end of the chain. An example such as (8a) would thus involve scattered deletion as in [PP af  ] ... [PP

] ... [PP  managein].Footnote 19

managein].Footnote 19

In contrast, if copy deletion takes place after reduction to P has occurred, then the preverbal af at the head of the chain instantiates a P head while the tail remains a full PP.Footnote 20 The two copies of the preverb are thus morphosyntactically non-isomorphic and distinct, resulting in Multiple Copy Spell-Out and P-Copying.

2.1.2 Tmesis

The basic intuition to be modelled is that P-Copying is possible when the preverb and verb form a tightly-bound morphophonological constituent (i.e., constitute a single prosodic word), and impossible when the preverb and verb each retain some prosodic independence. This parallels other examples of putative adposition doubling in which adjacency between the doubled element and verb is essential. Consider Dourado’s (2002) account [in Bošković and Nunes 2007, 59] of a similar phenomenon in Panará (Brazil: Northwestern Jê), which allows P-Copying with incorporated postpositions. In Panará, doubling of the postposition is only possible when the incorporated P and verb are linearly adjacent:

P-Copying as in (14b) is only licit when the incorporated postposition h w is directly adjacent to the verb tẽ; in (14a), the intervening subject agreement marker ria disrupts this adjacency, blocking P-Copying. Dourado analyses the deletion of this intervening agreement marker as a prerequisite for the process of incorporation which renders the postposition invisble to the LCA; this is clearly indicative of a locality requirement on Multiple Copy Spell-Out, where two items must be adjacent to form a unified prosodic constituent. In fact, Gothic displays a similar constraint on P-Copying when we look at the application of tmesis, the process by which a compound word is broken up by intervening elements.Footnote 21 This is exemplified in PVCs when a preverb is separated from its verbal stem by clitics:Footnote 22

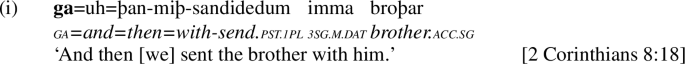

w is directly adjacent to the verb tẽ; in (14a), the intervening subject agreement marker ria disrupts this adjacency, blocking P-Copying. Dourado analyses the deletion of this intervening agreement marker as a prerequisite for the process of incorporation which renders the postposition invisble to the LCA; this is clearly indicative of a locality requirement on Multiple Copy Spell-Out, where two items must be adjacent to form a unified prosodic constituent. In fact, Gothic displays a similar constraint on P-Copying when we look at the application of tmesis, the process by which a compound word is broken up by intervening elements.Footnote 21 This is exemplified in PVCs when a preverb is separated from its verbal stem by clitics:Footnote 22

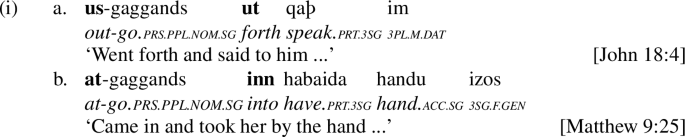

Crucially, non-adjacency between the preverb and verb prevents P-Copying: out of 14 attestations of tmetic PVCs with preverbs of prepositional origin, none co-occur with a PP headed by the same preposition as the separated preverb.Footnote 23 Instead, all tmetic PVCs either omit the expected preposition (16a) or employ a different preposition (16b):Footnote 24

In contrast, non-tmetic versions of these PVCs can show P-Copying. The PVC us-gaggan ‘to go out’ (with suppletive past stem iddj-) attests doubling 25 times as in (17a), while the tmetic variants with enclitics =uh ‘and’ and =þan ‘then’ fail to as in (16b) and (17b).

This complementarity falls out straightforwardly from the proposed account. The requirement for enclitics to have phonological hosts at their left edge forces displacement of the preverb to serve as such a host. This displacement may be either prosodic (i.e., at PF only) or syntactic; here I consider the former approach and discuss the syntactic alternative in footnotes 25 and 27.Footnote 25

Tmesis can be analysed as a post-syntactic phenomenon, occurring as a prosodic repair at the level of PF without any manipulation to syntactic structure. Mismatches in the mapping between syntax and prosody are well-established (Clemens 2014; Tan 2021; Tyler and Kastner 2022). For example, Clemens (2014, 2019) argues that prosodic displacement derives VOS surface order from underlying VSO syntax in Niuean. Recall the intuition that P-Copying involves erasure of the prosodic (word) boundary between the preverb and verb and, by extension, prosodic weakening of the preverb. Tmesis has a contradictory requirement: that the preverb be prosodically strong enough to serve as a host to clitics. If enclitics need to be adjacent to prosodic words, a preverb host must project its own prosodic word;Footnote 26 it cannot form a unified, opaque prosodic word with the verb and must remain visible for Chain Reduction, blocking P-Copying. While I leave a full analysis of the mechanisms involved to future work, the crucial generalisation is that tmesis and P-Copying are in complementary distribution; if a tmetic preverb is prosodically non-adjacent to the verb, it prevents formation of the complex prosodic word which renders it invisible for copy deletion.Footnote 27

As a whole, this subsection argues that P-Copying provides overt evidence for the presence of a movement chain wherein a preposition is incorporated into a PVC. We now turn to covert evidence that the preverb originates as such a preposition prior to incorporation.

2.2 Evidence for P-incorporation of a preposition: case and valency alternations

Preverbs do not simply add spatial/temporal semantics to the underlying verb; they also allow for additional indirect objects, like goals or sources. This affects the apparent argument structure of the base verb in several ways. For one, originally intransitive verbs can become (mono)transitive when combined with a preverb. The common intransitive verb gaggan ‘to go’ occurs either sans object (18a) or with an oblique PP (18b) across its approximately 220 attestations. The derived PVC þairh-gaggan ‘to go through’ has 12 attestations; of these, 5 show the complex verb taking an accusative-marked location as in (18c):Footnote 28

Similarly, the verb standan ‘to stand’ is intransitive across its 48 attestations, as in (19a). Out of 11 attestations as prefixed af-standan ‘to depart from, to stand apart from’, 4 show an apparent valency increase in taking a dative-marked source as in (19b).Footnote 29

In addition, originally (mono)transitive verbal bases can become optionally ditransitive when combined with a preverb. In (20a), the verb tauhun ‘pulled’ takes an accusative direct object Iesu ‘Jesus.’ All 14 attestations of un-prefixed tiuhan ‘to pull’ are either intransitive or monotransitive. In contrast, the prefixed verb at-tiuhan ‘to pull to, bring to’ in (20b) and (20c) is ditransitive and takes both an accusative direct object and a dative indirect object.

There is good evidence that the incorporated preverb originates as a preposition which introduces the additional arguments in these constructions. This is because the case marking on the additional argument always tracks that which is assigned by the preposition prior to its incorporation. The locative DP is accusative in (18c) because independent þairh always assigns accusative case (21a); the source DP is dative in (19b) because independent af always assigns dative case (21b).Footnote 30

As in German, some Gothic prepositions like ana ‘onto, on’ show semantically-determined case variability (Miller 2019, §6.5), taking accusative case when describing motion (22a), but dative case with static location (22b).

Crucially, these prepositions retain this semantic alternation when incorporated into PVCs. When ana describes motion in (23a), it assigns accusative case, but when evoking a static action in (23b), the case is dative:

In fact, the example of ana-haitan ‘on(to)’ + ‘call’ is particularly notable as this verb assigns accusative case to its direct objects when its semantics are ‘to invoke, call upon’, but dative when its semantics are ‘to scold, reprimand, rebuke’ (Miller 2019, 155–6). The fact that PVCs inherit the case-assigning properties of the pre-incorporation preposition is strong evidence that the preverb starts off as the head of a PP. The case-marking on these oblique DPs is simply the result of the P head assigning case to its complement prior to incorporation.

Here I lay out some brief assumptions about case assignment in Gothic. I assume that different prepositions are specified to assign a specific case to their complements, whether that is dative (as with af ‘from, away’), accusative (as with þairh ‘through’), or a semantically-determined combination of the two (as with ana ‘onto’ in (22)). Although a full account of the relationship between particular prepositions and the case they assign in Gothic (as well as ‘two-way’ locative/directional alternations) is beyond the scope of this paper, there are a number of ways to cash this out. One could simply stipulate that different p + \(\sqrt{\text {root}}\) combinations assign different cases as a type of inherent or ‘lexically-governed’ case as per Marantz (1991); cf. also Woolford (2006) on lexical case. Alternatively, based on approaches to adpositional case in Dutch and German (van Riemsdijk 2007; Den Dikken 2010; Caha 2010), PP-internal case assignment may be structural. On this approach, differences across prepositions can be captured by further decomposing PP into P\(_{\text {Loc}}\) (or ‘PlaceP’) and P\(_{\text {Dir}}\) (or ‘PathP’) optionally built atop of it, following the tradition of van Riemsdijk (1978); Jackendoff (1983); Koopman (1999). Taking the account in Den Dikken (2010, §5.5) for concreteness, he proposes that P\(_{\text {Loc}}\) and P\(_{\text {Dir}}\) may each be dominated by the functional heads Asp\(_{\text {Loc}}\) and Asp\(_{\text {Dir}}\) respectively (amongst others), where the former assigns dative case and the latter accusative case. Individual prepositions then differ as to the amount of functional material in the extended projection of P\(_{\text {Loc/Dir}}\), resulting in the structurally-determined assignment of accusative or dative case to their complements. For the purposes of this paper, what is crucial is that any such case assignment occurs within the domain of the PP (which may be phasal, cf. Abels 2003, 2012), rendering oblique DP complements inaccessible for subsequent case assignment and/or A-movement operations. I thus propose that all additional oblique DPs in non-idiomatic PVCs receive case PP-internally from specific functional heads (i.e., P or Asp\(_{\text {loc/dir}}\)) prior to incorporation, as evidenced by the case-tracking facts and semantic alternations discussed above.

In the larger clausal domain, I assume that there exists a variant of v, namely v\(_{\text {dat}}\), which is in a selectional relationship with particular verbs and which looks down into its c-command domain to assign dative case to the highest visible DP via Agree—a configuration independently required for monotransitive verbs such as bairgan ‘to protect’ and balwjan ‘to torture’ which take dative complements. This head contrasts with vP which assigns accusative case to the highest visible DP in its c-command domain and v\(_{\text {pass}}\)P which assigns no case at all and instead facilitates the promotion of arguments into Spec, TP for nominative case assignment with unaccusative verbs and in passive constructions (cf. Sigurðsson 2012 for discussion of such ternary systems).Footnote 31

Additional evidence for an incorporation-based account is the lack of valency alternations with two preverbs in particular: inn ‘into’ and ut ‘out’ (Vázquez-González and Barðdal 2019). There are no verbs which change their argument structure upon being prefixed with either of these two elements, precisely because they are the only two preverbs that have purely adverbial function when independent. This means that they lack the ability to introduce their own arguments prior to incorporation. The absence of valency increases with these two preverbs directly falls out from an analysis in which they originate as adverbs, incapable of taking DP complements (unlike prepositions) or introducing arguments in their specifier (unlike the Appl heads argued in Sect. 3.3 below for idiomatic PVCs).Footnote 32

The question remains of how exactly the apparent valency increase described above occurs. There are two possible analyses: firstly, incorporation of the P head could strand its original DP complement at the extraction site, giving the ‘illusion’ of valency increase. Alternatively, the oblique DP could instantiate a proper argument of the verb in some thematically-licensed position related to VP. Based on evidence discussed in the next section, I will argue that the former stranding analysis is more appropriate for non-idiomatic PVCs, and that the latter argumental analysis is more suitable for idiomatic PVCs.

Given both overt evidence from P-Copying and covert evidence from case and valency alternations, I propose that preverbs in non-idiomatic PVCs originate as prepositional heads prior to incorporation. Mechanically, this means they comprise a root in combination with a p categorising head, e.g., \(\sqrt{\text {af}}\) + p (Acedo Matellán 2010; Haselbach and Pitteroff 2015; Wood and Marantz 2017). This will now be shown to contrast with preverbs in idiomatic PVCs, where I argue they remain bare acategorial roots, e.g., \(\sqrt{\text {af}}\).

3 The structure of optionally idiomatic PVCs

Examples of idiomatic compounds as presented in (2) above are repeated here for convenience:

Let us first define what it means for something to be ‘idiomatic.’ Bucsko (2011, §4.3) suggests a tripartite cline of semantic transparency for any given compound: it may be fully idiomatic, metaphorical, or fully non-idiomatic. Fully idiomatic compounds are those in which the original meaning of the preverb and/or verb is no longer recoverable; they are completely non-literal. In contrast, metaphorical compounds are those where the meaning of either preverb or verb has been ‘extended’ in discernible ways. Finally, in non-idiomatic compounds both the preverb and verb retain their original semantics. This paper relies on a binary distinction between fully idiomatic compounds on the one hand and metaphorical/non-idiomatic compounds on the other.Footnote 33

This paper’s analysis of Gothic PVCs builds on the long-held intuition that differences in idiomaticity have structural correlates, where the licensing of ‘special meaning’ is configurationally and locally constrained (O’Grady 1998; Bhatt 2002; Bruening 2010; Anagnostopoulou and Samioti 2013; Marantz 2013; Bruening et al. 2018, a.o.). For example, Wurmbrand (2000) argues that surface-similar particle verbs in West Germanic have separate structures when semantically transparent as opposed to (semi-)idiomatic, an analysis expanded upon later in this section. This paper expands on this distinction to propose that optionally idiomatic PVCs have the structure in (25).

In contrast to obligatorily non-idiomatic compounds which involve incorporation and m-merger of the preverb, I argue that the preverb in optionally idiomatic compounds is first-merged as the acategorial head of a high applicative projection ApplP (Pylkkänen 2008), the specifier of which applied objects can be first-merged into. This difference in the derivational origin of the preverb determines the availability of idiomatic interpretation.Footnote 34 This section will first discuss the locality of idiomatic licensing, before presenting evidence against the existence of a movement chain akin to that found in non-idiomatic PVCs and in favour of an ApplP projection instead.

3.1 Idiomatic licensing

I adopt Wurmbrand’s (2000) proposal that idiomatic particles must be licensed in particular configurations:

I assume that the head-complement relation between the base-generated preverb in Appl and verb in VP as illustrated in (25) qualifies as just such a local relation, enabling (but not obligating) idiomatic interpretations. In contrast, strictly non-idiomatic compounds lack such a local relationship between the preverb in P and verb. One could argue that either the movement of P(P) into Spec, vP or its subsequent m-merger adjunction to v results in a sufficiently local relation in (7). However, it is clear from cross-linguistic parallels that we should not expect these derived configurations to suffice for idiomatic licensing. Consider for instance Modern German, where idiomatic interpretations are uncontroversially licensed in V2 constructions, even after the verb has fronted to C and stranded its complement or particle:

In fact, it is widely accepted that idioms are not sensitive to surface structure/PF but something deeper such as LF, ‘the point of Merge’, or traditional D-structure (Bhatt 2002).Footnote 35 Proposals like O’Grady’s (1998) Dependency Theory and Bruening’s (2010) Selection Theory rely on the conditions of external Merge:

The availability of idiomatic readings in (27) is thus easily accounted for if the verb has either reconstructed, left a privileged copy, or not moved at all at LF such that head-movement of V does not affect idiomatic licensing (Wurmbrand 2000). The flipside of this suggests that if the proper idiomatic licensing configuration does not obtain at first-merge or LF, one cannot derive it—in the same way thematic relations are established at first merge, so too are idiomatic relations. This precludes idiomatic licensing from happening in semantically-transparent Gothic compounds like (7): because the preverb starts out as head of a PP it is non-local for (26) and/or (28).Footnote 36 Thus, (non-)idiomaticity can be said to fall out from the proposed presence of incorporation in transparent but not idiomatic PVCs; I will now proceed to demonstrate this absence in idiomatic PVCs and illustrate how the structure in (25) successfully derives other asymmetries in the distribution of the two types of Gothic compounds in the form of case and argument structure alternations.

3.2 Evidence against P-incorporation: no P-copying or case tracking

It is notable that idiomatic PVCs can show a valency increase over their non-prefixed versions. Consider the unaccusative verb qiman ‘to come’, which becomes transitive when prefixed with us ‘out’ and acquires the non-compositional meaning ‘to kill’, taking a dative object:

On the surface, this could involve the same structure as proposed for non-idiomatic PVCs in Sect. 2 wherein us introduces the oblique argument Iesua as its complement prior to its incorporation. However, I argue that these compounds instead employ applicative projections headed by the preverb, where the applied object is first-merged in Spec, ApplP. The first piece of evidence for this is that idiomatic PVCs never show P-Copying. One could imagine a construction like (29) with doubling of us before the applied object Iesua ‘Jesus’ for emphatic purposes or as a remnant of the underlying spatio-temporal meaning (‘out of Jesus’), the result of Multiple Copy Spell-Out as discussed in Sect. 2.1.1 above.

However, across approx. 455 tokens of idiomatic PVCs in the Bible built with preverbs of prepositional origin (spread across 38 types, given in Appendix B.2), P-Copying is almost exceptionlessly absent.Footnote 37 This is predicted by our analysis of idiomaticity: if the preverb starts out bearing its original locative meaning in a PP, there is no way for it to later produce idiomatic meaning upon incorporation, since all links in a movement chain must bear the same ‘status’ regarding semantic transparency. Hence, the absence of ‘idiomatic’ P-Copying falls out from how there is no movement chain of which multiple links can be pronounced when an idiomatic preverb is first-merged as an Appl head.

The corollary of this is that idiomatic preverbs cannot introduce their own complement. The second piece of evidence that preverbs do not originate in PPs then comes from patterns of case-assignment to applied objects. Recall how Sect. 2.2 showed that the added objects of non-idiomatic compounds track the case assigned by the independent preposition prior to incorporation, including any semantic alternations. This was taken as evidence that these preverbs started out as prepositions, assigning case to their complement before movement. No such tracking obtains with idiomatic PVCs: applied objects can be assigned dative case even when the original preposition only ever assigns accusative case (and vice versa). For example, the independent preposition and ‘throughout, along’ only ever introduces accusative complements, but co-occurs with dative applied objects in and-tilon ‘to hold to, to be devoted to’ (< *-tilon from PGmc. *tilōną ‘to strive, reach’; cf. Got. ga-tilon ‘to achieve, obtain’) and and-hafjan ‘to answer’ (< hafjan ‘to raise, lift’):

Similarly, the dative-assigning preposition us ‘out of’ co-occurs with an accusative applied argument when prefixed to intransitive waltjan ‘to roll (of waves)’, producing the transitive verb us-waltjan ‘to subvert, overthrow’:

The independent verb hafjan takes an accusative direct object, while the verb waltjan is intransitive. It is clear that the case-assigning ability of these idiomatic PVCs is not compositionally inherited from either of its component parts, but is instead a property of the complex PVC in its entirety (just as the stored idiomatic interpretation is a property of the preverbal Appl head + verb together). This parallels how inseparable prefixes like fra- ‘away, forward, pejorative’ can increase valency while co-occurring with dative-marked objects:

Again, the ability to assign dative case cannot come from the verbal base, which is intransitive qiman ‘to come’ in (32a) and which takes accusative direct objects as bugjan ‘to buy’ in (32b). Similarly, it cannot come from the preverb, since fra- does not exist as an independent preposition.Footnote 38 Thus, I posit that all PVCs headed by inseparable prefixes like fra-, dis-, or twis- involve the ApplP structure of an optionally idiomatic compound even when semantically transparent, given that there is no PP they could originate as the head of and subsequently incorporate from.

If case does not track the prepositional variant of the preverb (contra non-idiomatic PVCs), what determines whether a given idiomatic PVC’s complement is accusative or dative? Here I propose that dative-assigning idiomatic PVCs are those whose Appl-V complex is in a selectional relationship with a v\(_{\text {dat}}\)P, such that the highest visible DP first-merged in Spec, ApplP receives dative case under Agree with v\(_{\text {dat}}\). Thus, a dative complement PVC like and-hafjan ‘to answer’ will have a similar syntactic structure to that of a simplex dative complement verb like bairgan ‘to protect’, except that v\(_{\text {dat}}\)P combines with ApplP rather than VP directly and the highest visible DP is in the specifier of ApplP rather than the complement of VP. Idiomatic PVCs which take accusative complements like us-waltjan ‘to overthrow’ simply combine with vP, such that v assigns accusative case to the DP in Spec, ApplP as with conventional accusative complement verbs like maitan ‘to cut’.Footnote 39

In sum, the exact phenomena of P-Copying and case tracking which support the presence of P-Incorporation in non-idiomatic compounds confirm the absence of this incorporation in idiomatic compounds. The next section will present further evidence that additional objects introduced by ApplP in idiomatic PVCs are real arguments of the extended verbal projection and not stranded within a PP adjunct, contra non-idiomatic PVCs.

3.3 Evidence for ApplP: valency alternations and passivisation

As proposed by Pylkkänen (2002, 2008) and widely adopted thereafter, I assume that some valency-increasing constructions employ an applicative projection ApplP. The high variant of ApplP, merged between v/VoiceP and VP, introduces and thematically licenses arguments like beneficiaries, maleficiaries, and locations in its specifier and relates them to the event described by the complement VP.

We have seen that preverbs in idiomatic PVCs show different empirical behaviour in comparison to those found in non-idiomatic PVCs. In particular, they do not participate in P-Copying and show no correlation between the case their prepositional variants assign and the case assigned to direct objects of the idiomatic PVC. I argue that this is because the preverb in idiomatic PVCs instantiates the head of such an aforementioned high ApplP. The proposed structure is illustrated in (33) and closely resembles that proposed by Wurmbrand (1998, 270: ex. 4b) for prefix verbs in Modern German as illustrated in (34).Footnote 40

In both, the preverb/prefixal element instantiates the head of a functional projection which combines with a VP complement; the main differences between (33) and (34) are the label of this functional projectionFootnote 41 and the category (or lack thereof) of the preverb/prefix itself (addressed in Sect. 3.4). Crucially, in these constructions the DP introduced by this additional functional projection behaves as a proper argument of the verb for the purposes of argument structure alternations (Stiebels and Wunderlich 1994). We can illustrate this fact through the contrast between prefix and particle verbs in Modern German. The former are valency-increasing (35a) while the latter are not and instead require prepositions to introduce additional arguments (35b).

Wurmbrand (1998) analyses this difference as arising from how the two complex verbs in (35), be-treten and ein-treten, have different underlying structures. Bearing the structure in (34), here updated with the label ApplP (36a), the prefix verb betreten introduces the locative object in Spec, ApplP. In contrast, the particle verb eintreten introduces the locative object within a PP adjunct as in (36b).Footnote 42

As the locative DP is an argument of the (extended) prefix verb in (36a) but in an adjunct of the particle verb in (36b), only the former may be passivised:

We can recreate this contrast in Gothic. The proposal is that idiomatic PVCs introduce additional objects as arguments in Spec, ApplP, while non-idiomatic PVCs show ‘valency increase’ when the incorporated preposition strands its complement DP within the PP it originates from. As such, idiomatic PVCs should allow applied objects to be passivised and promoted to subject position. For instance, the unergative verb laikan ‘to leap for joy, play’ (38a) forms an idiomatic PVC with bi- ‘by, at’ such that bi-laikan is a transitive verb meaning ‘to mock’ (38b).Footnote 44 Crucially, the newly introduced applied object can then be passivised in (38c):

Similarly, the intransitive verb qiman ‘to come’ combines with inseparable particle fra- ‘away, forward, pejorative’ to produce idiomatic fra-qiman ‘to expend, use up’ whose object can be passivised:

The availability of passivisation shows that Gothic idiomatic PVCs behave like German prefix verbs in merging the applied object as an argument of the extended verbal complex in Spec, ApplP, instantiating a real valency increase. Here I assume that passivisation involves a v\(_{\text {pass}}\)P taking ApplP as its complement. Since v\(_{\text {pass}}\) does not assign any case (unlike v with accusative and v\(_{\text {dat}}\) with dative), we find syntactic promotion of the highest visible DP as it raises into subject position in Spec, TP to receive nominative case from T. Crucially, even idiomatic PVCs which admit dative objects can be passivised (cf. fra-qimada ‘(3sg) is spent, used up’ in (39)). I assume that this is because these objects receive dative case from v\(_{\text {dat}}\); as v\(_{\text {dat}}\) is in complementary distribution with v\(_{\text {pass}}\), the DP argument remains unmarked for case and thus visible for promotion.Footnote 45

in contrast, the complements of prepositions in Gothic cannot be promoted under passivisation, just as in Modern German. One reason for this may be that they receive PP-internal case from the preposition that introduces them, rendering them invisible to subsequent A-movement operations; another reason is that they originate within an adjunct and cannot be extracted. As such, passivised non-idiomatic PVCs should not allow the promotion of nominals introduced by the (prepositional) preverb. We can test this in three main ways.

Firstly, intransitive verbs which become ‘derived transitives’ upon preverbation (with the added object clearly associated with the prepositional preverb) should not allow for passivisation or promotion of this object. Indeed, out of approximately 195 attested tokens of (synthetic) passives (Skladny 1873, 3–7),Footnote 46 none involve a transitive PVC built off of an intransitive verbal base (e.g., ana-qiman ‘to come upon X’ but no **ana-qimada ‘(3sg) is come upon’; bi-standan ‘to stand around, surround X’ but no **bi-standada ‘(3sg) is surrounded’).Footnote 47

However, transitive verbs which form transitive PVCs with no alteration of their argument structure can be freely passivised with promotion of the verb’s direct object argument. For example, a monotransitive PVC us-siggwan ‘to read out, recite X’ built off of a monotransitive verb siggwan ‘to sing, read X’ allows promotion of the direct object under passivisation since the Theme is originally introduced by the verbal base as in (40).

Crucially, when a transitive verb becomes a ‘derived ditransitive’, only the direct object thematically introduced by the original verb can be promoted under passivisation—never the additional oblique nominal associated with the preverb. Thus, PVC af-niman ‘to take X from Y’ built off of monotransitive niman ‘to take X’ can be passivised (41a), but only with promotion of the original Theme argument þat ‘that (which he has)’ and not the Source imma ‘him’ introduced by af. The reason for this can be seen transparently in cases of P-Copying, where the oblique nominal overtly remains in a PP and is therefore unavailable for promotion (41b).Footnote 48

Indeed, all ‘derived ditransitive’ non-idiomatic PVCs show this promotion asymmetry under passivisation, permitting only the promotion of direct objects first introduced by the verbal base. This pattern of alternation is exemplified non-exhaustively in Table 2. What these alternations show is that additional arguments introduced by the preverb in non-idiomatic PVCs cannot be promoted under passivisation, suggesting that they behave more like German particle verbs in introducing the locative/oblique object within a PP.

This section has provided evidence from argument structure alternations for the presence of a valency-increasing applicative projection in idiomatic PVCs, contra non-idiomatic PVCs; the structures for each have been shown to parallel Modern German prefix and particle verbs respectively. Crucially, idiomatic PVCs introduce applied objects as arguments in Spec, ApplP, which receive case on the basis of Agree with a v or v\(_{\text {dat}}\) head and are available for promotion under passivisation when in combination with v\(_{\text {pass}}\). In contrast, non-idiomatic PVCs only show the illusion of valency increase, such that any additional objects are really DPs stranded within the PP adjunct vacated by the preverb when it incorporates. They hence closely track the case assigned by the prepositional variant of the preverb (down to acc/dat alternations conditioned by motion vs. static location semantics) and cannot be promoted to subject under passivisation.

3.4 Roots and categories

The differences between idiomatic and non-idiomatic PVCs described above can be captured by proposing that preverbs instantiate an Appl head in the former and a P head in the latter. What does it mean for a preverb to be Appl? Here, I follow recent work on semi-lexicality which proposes that roots are structural notions, constituting a type of (terminal) syntactic node (De Belder 2011; De Belder and Van Craenenbroeck 2015; Cavirani-Pots 2020). Any vocabulary item can realise a root if it is inserted into a root position; many vocabulary items can be used functionally if inserted into a non-root position. As such, conventionally functional items can be used lexically (e.g., Dutch maar ‘but’ forming a verb maaren ‘to object’; German du 2sg.nom forming a verb duzen ‘to address (informally) with du’) and vice versa (e.g., Dutch zitten ‘to sit’ coming to mark progressive or durative aspect).

For a given preverb af ‘from, away’, I propose that it instantiates a root \(\sqrt{\text {af}}\) that may either be combined with categorising head p to form a preposition (following proposals by Acedo Matellán 2010; Haselbach and Pitteroff 2015; Wood and Marantz 2017), or with Appl to form an applicative head. In its prepositional use (42a), \(\sqrt{\text {af}}\) + p can not only introduce its own DP complement but also determine the thematic role it receives and the case it is assigned. In its applicative use (42b), Appl can introduce an applied argument in its specifier—but the case this applied object receives is based on the vP it combines with (e.g., accusative with v (38b), dative with v\(_{\text {dat}}\) (32), or nominative when passivised with v\(_{\text {pass}}\) as in (39) and (38c)).

This analysis captures the case-tracking behaviour we find with non-idiomatic PVCs but not idiomatic ones, as well as the passivisation facts we find wherein oblique objects as in (42b) cannot be promoted while applied objects as in (42a) can. Furthermore, the fact that P directly assigns a (spatio-temporal) thematic role to its complement in (42a) precludes subsequent idiomatic interpretation, while the applied object in (42b) has more flexibility in receiving a theta role from the (potentially idiomatic) Appl + \(\sqrt{\text {af}}\) + V complex.Footnote 49

3.5 Alternative possibilities

One could posit that idiomatic PVCs are first-merged as an indivisible lexical item, illustrated as follows:Footnote 50

As with the purported outcome of Morphological Fusion discussed above (Sect. 2.1.1), this would suggest that the preverb and verb are stored as an inseparable unit in the Lexicon and inserted as such at Spell-Out, and faces similar issues. Firstly, idiomatic PVCs always inherit the inflection class of the verbal base, even when the semantic contribution of that base is completely opaque—qiman ‘to come’ and hafjan ‘to lift’ are both strong verbs (Class IV and VI respectively). Their idiomatic counterparts in (29) and (30b) inherit these ablaut patterns exactly, which one would have to say is coincidence or analogy under a structure like (43).

Secondly, idiomatic compounds allow tmesis (44). It may seem odd that the lack of linear adjacency does not block idiomatic interpretation; however, recall that idiomatic licensing occurs at first merge, such that subsequent displacement of the preverb should not affect its interpretation (Sect. 3.1).Footnote 51

The fact that tmesis can target the preverb as an individual prosodic element for displacement to host intervening clitics suggests not only its phonological but also its structural independence from the verb. If the preverb were truly inaccessible, we would expect tmesis to treat the entire compound as one undecomposable unit with clitics occurring after the the prefixed verb (e.g., **bi-gitanda=uh=þan), as in simplex verbs:Footnote 52

Thus, idiomatic PVCs cannot involve Vocabulary Insertion of an opaque preverb + verb unit to a single terminal node, as verb base idiosyncracies and tmesis both attest some decompositionality of the preverb and verb. Alternatively, we could posit a looser structure where the preverb instantiates a full complement of the verb:

This structure is akin to Wurmbrand ’s (1998, 2000) proposal for Modern German semi-idiomatic particle verbs in (36b). However, this analysis also makes incorrect predictions for Gothic: for one, German particle verbs obligatorily strand their particle in final position when the verb is moved for V2, as exemplified in (27).Footnote 53 In contrast, neither idiomatic nor non-idiomatic Gothic PVCs ever strand their preverb in configurations that require V-fronting:Footnote 54

It has been established that wh-items consistently trigger V2 in Gothic (Eythórsson 1995; Walkden 2012; Miller 2019), such that nothing intervenes between the verb and interrogative element. Thus, the PVCs in (47a) and (47b) must have undergone fronting to C; yet both the semantically transparent preverb us ‘out (of)’ and idiomatic preverb and ‘throughout, along’ remain prefixed to the verb. Similarly, the interrogative clitic =u is taken to reside in C, attaching to highest overt head of the complex which moves into it (Eythórsson 1995, §2.2, §3.2). In positive questions, this overt head is simply the verb; in negative questions, this is the negator (assuming head movement of V \(\rightarrow \) Neg). Given this, (47c) also requires movement of the verb to CP, but shows no stranding of and. Finally, recall that German particle verbs cannot increase valency (35b), while idiomatic PVCs in Gothic can (Sects. 3.2 and 3.3). With these differences in the (un)availability of stranding and argument structure alternations, it is clear that Gothic PVCs and German particle verbs must have different structures.

3.6 Interim summary

Having established the differing underlying structures of the surface-similar obligatorily semantically transparent and optionally idiomatic PVCs, we can summarise their empirical behaviour as in Table 3.

Non-idiomatic PVCs involve a movement chain in which the head of a prepositional phrase incorporates into the verb via m-merger. This prepositional head determines both the case and thematic role of its underlying DP complement, ‘locking in’ its non-idiomatic semantics and resulting in case tracking; however, because this added oblique DP remains stranded in the PP, it is not a genuine argument of the verb and remains unavailable for A-movement operations like passivisation. Non-idiomatic PVCs therefore fail to show true valency increase. Multiple Copy Spell-Out of more than one link of the incorporation movement chain results in P-Copying, which requires adjacency of the preverb + verb and is thus disrupted by tmesis.

In contrast, idiomatic PVCs involve the preverb first-merged as an Appl head, which takes a VP complement (allowing for local idiomatic licensing) and can introduce applied object arguments in its specifier. As with the direct object of simplex verbs, these applied arguments are visible for case assignment via Agree with v(dat), eschewing case tracking. Similarly, they are available for promotion under passivisation. The absence of a movement chain precludes P-Copying, but not tmesis—showing that the idiomatic preverb + verb compound must remain decomposable at some level, given also the retention of idiosyncratic verb class morphology. However, the idiomatic preverb + verb must form a complex head at some point, given the absence of stranding.

4 The structure of multiple preverb compounds

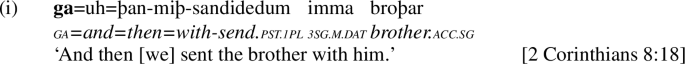

The stage is now set for an analysis of multiple preverbation, which is argued to involve a combination of the two structures proposed above for obligatorily non-idiomatic and optionally idiomatic PVCs in Gothic. Examples of Multiple Preverb Compounds (MPCs) are given in (48), reiterated from (3) above; a full list of attested MPCs is given in Appendix B.3. The structure proposed for MPCs is given in (49) and is essentially that of a non-idiomatic PVC built on top of an idiomatic PVC.

The compound begins with an optionally idiomatic PVC structure (i.e., ApplP + VP) which takes a PP adjunct.Footnote 55 Just as in strictly non-idiomatic PVCs, the head of this PP undergoes incorporation and m-merger; however, instead of combining with a simplex V-v, it here combines with the complex Appl-V-v. On this account, MPCs are predicted to display mixed behaviour with respect to the empirical traits discussed in prior sections.

4.1 Outer vs. inner preverbs

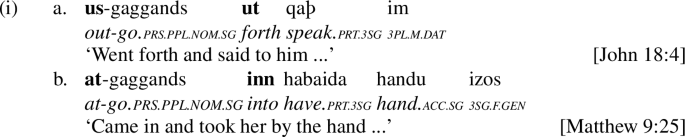

There are four pieces of evidence for MPCs involving both P-Incorporation of the outer preverb and an ApplP headed by the inner preverb, which are all by now familiar: P-Copying, idiomatisation, valency increase with/out case tracking, and tmesis. To begin, P-Copying is attested with MPCs, but only with the outermost preverb:

Despite similar meanings, we do not get repetition of inn to express or reinforce motion into the temple.Footnote 56 This suggests that the outermost preverb involves a movement chain which can undergo Multiple Copy Spell Out as in Sect. 2.1, unlike the innermost preverb.

The second piece of evidence comes from the unavailability of idiomatic meaning: the peripheral preverb never contributes additional idiomatic meaning to the complex, indicating that it does not originate in a local relationship with the verb. Instead, its contribution is always spatio-temporal:

The outermost preverb always bears completely transparent meaning. Even when the original PVC is idiomatic (e.g., in-sakan ‘in’ + ‘to rebuke’ = ‘to set before, present evidence’), the second preverb does not add more idiomatic or metaphorical meaning (‘onto’ + ‘to set before, present’ = ‘to contribute to’). Indeed, a similar observation is made by Bucsko (2008, 77) that “outer layers of derivation do not normally produce idiomatic value.” This shows that the peripheral preverb behaves like an incorporated preposition in retaining its transparent semantics.

Thirdly, MPCs allow for apparent valency increase, but only add a single additional object—no MPC is ‘tritransitive’. For instance, miþ-in-sandjan means ‘send X with Y’ (52a), not ‘send X to Y with Z’ , even though in-sandjan is a “derived ditransitive" built off of the underlyingly monotransitive verb sandjan ‘to send’ (52b).Footnote 57

Crucially, the single indirect/oblique object that does get added is semantically related to the peripheral preverb and not the innermost one, and always takes the case assigned by the relevant independent preposition. As independent du ‘to’ and miþ ‘with’ always assign dative case, while faur ‘before’ assigns accusative, we find the same case pattern in MPCs:

In this way, MPCs show the same case-tracking and ‘valency increasing’ behaviour as non-idiomatic PVCs, controlled by the outermost preverb.Footnote 58

Finally, consider how tmesis is employed in MPCs: clitics only intervene between the two preverbs, and not between the inner preverb and verb:

Assuming the post-syntactic analysis of tmesis as discussed in Sect. 2.1.2 above, this pattern is predicted by the structure in (49)—prosodic displacement targets the leftmost prosodic word of the MPC, which in this case instantiates the outermost preverb (and precludes P-Copying), resulting in [PreV1=Clitic-PreV2-Verb] order. Deriving [PreV1-PreV2=Clitic-Verb] order would require that both preverbs comprise a single prosodic word which can be displaced as a unit; there is no way to form this unit given the preverbs’ non-constituency in (49); any prosodic word that includes both the outer and inner preverb must also include the verbal base.Footnote 59

In sum, the distribution of P-Copying, idiomaticity, valency alternations with case tracking, and tmesis all suggest that the peripheral preverb should be analysed like in Sect. 2 as involving P-Incorporation, while the innermost preverb should be analysed like in Sect. 3 as the head of an ApplP.

4.2 Preverb ordering

Given existing work on the ordering of preverbs in MPCs across Indo-European (McCone 1997; Rossiter 2004; Papke 2010; Imbert 2008; Zanchi 2014, 2019), it is worth exploring whether any ordering tendencies exist in Gothic MPCs. Table 4 presents the multiple preverb combinations attested in Gothic.Footnote 60

As observed by Wolmar (2015), the attested combinations suggest the relative ordering in Table 5.Footnote 61

Sections 2 and 4.1 have demonstrated that the preverb in non-idiomatic PVCs and on the outer edge of MPCs retain adpositional behaviour in the form of oblique DP introduction and case assignment. As mentioned in Sect. 2.2, directional phrases have long been proposed to have complex internal structure (van Riemsdijk 1978; Jackendoff 1983; Koopman 1999), with a basic distinction between static location PlacePs and directed motion PathPs built atop of PlacePs. Subsequent work has not only attempted to uncover more fine-grained hierarchies within the PP (Svenonius 2010; Pantcheva 2011), but extended this approach to other types of directional expressions, as with Radkevich’s (2010) work on the cross-linguistic ordering of suffixing local cases (e.g., essive, allative) which shows that cases involving static location occur more internally than those involving motion (i.e., N-Place-Motion).

As such, there are a number of observations which can be made from the ordering in Table 5. Firstly, there is a general tendency for preverbs involving motion (e.g., inn ‘into’, ut ‘forth’, ana ‘onto’, du ‘to(wards)’, us ‘out of’) to occur more peripherally than those involve static location (e.g., at ‘at’, bi ‘by’, faur ‘in front of’, in ‘in’, uf ‘under’). As discussed in Miller (2019, §6.37), this can be captured by the adpositional hierarchy of Source > Goal > Place (Pantcheva 2011), wherein Source and Goal can be thought of as further elaborations of the directed motion PathP occurring peripherally to the static location PlaceP.Footnote 62

Secondly, preverbs of adverbial origin such as inn ‘into’ and ut ‘forth’ seem to occur more peripherally than those of prepositional origin. One potential reason for this is that neither of these adverbs form any idiomatic PVCs (cf. Appendix B.2). Thus, it may be that they were less inclined to instantiate the ApplP structure required to serve as the innermost preverb + verb complex for these MPCs, both synchronically and diachronically.Footnote 63

Lastly, comitative miþ ‘with’ prefers to occur most peripherally. This is not surprising, as its semantics of accompaniment are distinct from the spatio-temporal and directional-locative meanings expressed by the other preverbs. There are a number of parallels for this external positioning—for one, Miller (2014, 128), draws from similar ‘preposition-stacking’ phenomena in English lexicogenesis to argue that the thematic relations hierarchy Instrument > Location > Result results in elements like ‘with’ occurring more externally. Similarly, Caha (2009) identifies the Comitative and Instrumental cases as the most peripheral on his case hierarchy, external to the Dative, Genitive, Locative, Accusative, and Nominative.Footnote 64 Thus, looking at both adpositional and case-based hierarchies, the occurrence of miþ as the most peripheral preverb in MPCs is predicted cross-linguistically; I here describe its comitative and instrumental functions with the label Manner.

We can therefore revise the relative ordering in Table 5 to show that the preverb ‘slots’ in Gothic potentially instantiate meaningful categorial differences, as in Table 6. This ordering has clear parallels in the structure of local cases, directional expressions, and their role in lexicogenesis cross-linguistically.Footnote 65

5 Diachrony

Having discussed the synchronic significance of Gothic PVCs, we can briefly assess their diachronic development. As argued by Miller (2019, §6.43), Gothic instantiates an intermediate step between the stages of P-Incorporation and univerbation; I propose that these stages are represented by obligatorily non-idiomatic and optionally idiomatic compounds respectively. The phenomena of P-Copying, case/valency alternations, and idiomatisation all relate to a change in the functional status of these preverbs. In particular, PVCs involve reduction of both the independence of the preverb and the internal structure of the verb compound. This change may be described as an instance of grammaticalisation, where a lexical or grammatical unit comes to acquire increasingly grammatical function (Heine et al. 1991); one of the primary processes involved in grammaticalisation is syntactic reanalysis, where the underlying structure of an expression is changed without “immediate or intrinsic modification of its surface manifestation” (Langacker 1977, 59). Consider instances of PVCs involving P-Incorporation without P-Copying, which would be surface ambiguous between the following underlying structures:

Given canonical Chain Reduction (sans Multiple Copy Spell-Out), a learner might postulate the structure in (55b) rather than (55a), given that both result in the same surface string: [Preverb-Verb Obj]. I hence posit that non-idiomatic compounds are the ‘older’ more analytic form of the PVC, while idiomatic ones instantiate a later synthetic development. Recall the two main differences between the structures in (55): i) the category of the preverb, and ii) the absence of movement and m-merger of the preverbal element. I argue that both of these involve a well-motivated diachronic change.Footnote 66

The former change where a preverb goes from instantiating a P head to an Appl head constitutes a form of Upwards Reanalysis (Roberts and Roussou 2003; van Gelderen 2004), in which an element is preferentially interpreted as a functional head first-merged as late/high in the structure as possible. As in Cavirani-Pots’s (2020) proposed development pathway for semi-lexical roots, building on Song (2019), what begins in Stage I (55a) as a categorised root (p + \(\sqrt{\text {root}}\)), comes in Stage II (55b) to instantiate an actegorial root merged together with a syntactic feature (Appl + \(\sqrt{\text {root}}\)). This forms a complex functional head (Appl\(^{\circ }\)) which is merged in the functional domain of another lower root (i.e., v + \(\sqrt{\text {root}}\)). This categorial change exemplifies typical grammaticalisation as per the following cline, accompanied by phonological reduction:

We can further specify this as involving the following pathway for syntactic reduction (van der Auwera 1999):

Most Gothic preverbs are part-way down these pathways, beginning as independently projecting AdvPs or PPs prior to incorporation; at the P-Incorporation stage, these preverbs become non-projecting heads, surfacing either as clitics (when available for tmesis) or affixes (especially when P-Copied); the preverbal Appl head of idiomatic PVCs is also the result of reduction to just a prefix.

This shift goes hand-in-hand with the second change, being the loss of movement steps. The diachronic shift from Move to Merge is thought to be driven by the greater economy of the latter operation (van Gelderen 2004, 2011). Without evidence for a more articulated structure, learners can and will posit an underlying representation with less derivational complexity. Given that the evidence for incorporation (55a) comes from nuanced case-tracking and passivisation facts, any non-P-Copying, active instance of an ‘added’ object which is syncretic for accusative and dative case co-occurring with a preverb whose prepositional equivalent could only assign one of the two would obscure the distinction between the structures, allowing one to posit the second, simpler derivation (55b).

The diachronic development of Gothic preverbs closely parallels the prefix cline proposed by Los et al. (2012) for resultative complex verbs in West Germanic, which they claim involve the univerbation of a verb with its resultative phrase complement (ResP) following the cline in (57).Footnote 67 Consider the proposed syntactic development pathway for Gothic PVCs in Table 7, adapted from (Los et al. 2012, 174).

In Stage 1, preverbs are independent adpositions that head their own PP; unambiguous examples of this include sentences wherein these P heads take complements, as in (58a). However, sentences wherein the PP contains no material other than the head give rise to ambiguity between Stage 1 and 2/3, as in (58b).Footnote 68

At Stage 4, these preverbs have undergone P-Incorporation (55a), involving movement and m-merger of the PP. Unambiguous evidence of incorporation would involve a bare P head occurring in a pre-verbal position adjacent to the verb rather than its original complement. At this stage, both copied and non-copied variants are possible as depending on the variable order of Chain Reduction and m-merger (Sect. 2.1.1) and the presence of tmesis. Finally, at Stage 5, preverbs are reanalysed as the base-generated head of ApplP (55b). This reanalysis is facilitated by instances of Stage 4 without clear case-tracking between the preverb and its prepositional counterpart and/or with canonical Chain Reduction (i.e., no P-Copying). Thus, all optionally idiomatic PVCs and PVCs with inseparable prefixes are at Stage 5, while semantically-transparent PVCs which show case-tracking and P-Copying are still at Stage 4. Note that PVCs at any stage are free to take additional PP/AdvP adjuncts, entering Stage 1 again (cf. (16), (40), and footnote 63).

This re-entry into the cycle is what produces MPCs. Crucially, every PVC (whether idiomatic or not) which serves as the base for multiple preverbation must also be at Stage 5, for reasons described in Sect. 4 above. Actual MPCs on the whole have only reached Stage 4 of their ‘second cycle’, given the unavailability of additional idiomatic meaning as contributed by the peripheral preverb. This discussion emphasises how grammaticalisation is a process holding over particular constructions, rather than languages as a whole: different compound types may have reached different diachronic stages of the same cycle at a given point in time of synchronic analysis. In sum, we can identify several bridging contexts for transitioning between stages: PPs comprising just their heads (1 > 2/3), canonical Chain Reduction (sans P-Copying) (4 > 5), and the incorporation of a P whose complement is syncretic for case (4 > 5). The change from Stage 2/3 > 4 is simply the productive process of P-Incorporation.

The structures presented throughout this paper therefore not only derive the synchronic distribution of three types of Gothic PVCs—transparent, idiomatic, and multiply-prefixed—but also capture the diachronic relationship amongst them as paralleled elsewhere in Germanic.

6 Conclusion

This paper has closely examined both the synchronic status and diachronic development of preverb compounds in Gothic. It has presented a formal account of obligatorily non-idiomatic, optionally idiomatic, and multiple preverb compounds in Gothic. By distinguishing between the preverb as the outcome of incorporation and m-merger of a P head in non-idiomatic PVCs or as obtained at first-merge as an Appl head in idiomatic PVCs, this paper has derived the different behaviour of these compounds with respect to i) the availability of idiomaticity (requiring a local licensing relationship), ii) case assignment (as assigned by P but not Appl), iii) valency alternations (allowing promotion under passivisation of objects introduced by Appl but not those stranded by P), iv) P-Copying (requiring a movement chain and blurring of prosodic boundaries), and v) tmesis (requiring prosodic independence of the preverb), where the latter two are in complementary distribution. We have also seen that MPCs involve a combination of these two structures, where the peripheral preverb is an incorporated P but the inner preverb is first-merged as an Appl head. The empirical distribution of these PVC types is summarised in Table 8.

This paper has also presented a possibly cyclic diachronic development pathway for these Gothic preverb compounds, invoking processes of grammaticalisation and (upwards) syntactic reanalysis. This approach parallels similar changes in the history of West Germanic and may be extendable to languages with greater degrees of preverb stacking (e.g., Old Irish). Looking to languages with corpora spanning greater amounts of time would allow for the testing of our hypotheses by assessing the relative frequency of certain bridging constructions and the rate of transition between stages over time. In sum, it is clear that Gothic can and does exhibit independent, linguistically-significant morphosyntactic phenomena which may help us in elucidating formal approaches to synchronic structure and diachronic change.

Notes

In glossed examples of idiomatic PVCs throughout this paper, both the preverb and verb stem are glossed with their transparent base semantics but translated in their idiomatic meaning.

Although the primary manuscript source—the Codex Argenteus—is itself a 6th Century copy of the original text.

The University of Antwerp’s Project Wulfila corpus has been indispensable for data analysis as a digitised version of Streitberg (1919).

Appendix C provides a comparative overview of preverbs across Indo-European and their ordering in multiple preverb compounds.

See Metzger (1977, 385) for a discussion of the possibilities.

All Greek sourced from the 28th critical edition of the Nestle-Aland New Testament, the foremost reference for Biblical Greek.

As expanded on in Sect. 2, the tree in (4a) shows the outcome of m-merger and should not be taken to represent simple head movement of P (which would violate the Head Movement Constraint). However, both structures in (4) do involve actual head movement of V-to-v and V-to-Appl-to-v respectively. Arrows representing these latter movements are omitted from the trees for ease in presentation.