Abstract

Verb-initial ordering may be derived by fronting the VP (or a larger constituent) to a specifier position higher than the subject. For VSO languages, this analysis requires that the object raise out of the VP to a position below the subject before the (remnant) VP fronts to the higher position. This paper builds a comprehensive analysis of VSO order in the Polynesian language Samoan, employing the VP-fronting analysis, arguing the account does better than competing derivational accounts (e.g., a head movement account). I argue that evidence for the raising of the complement of V to a VP-external position comes from data showing that the coordination of unaccusative and unergative verbs is not possible in Samoan. This paradigm has a ready explanation under the VP-fronting account: as the complement of V must raise out of the VP before VP-fronting takes place, unaccusative subject DPs are predicted to bind a VP-internal copy. This blocks coordination with unergative VPs which do not contain DP copies (via the Coordinate Structure Constraint). I provide a generalized account of DP movement whereby the functional head v is specified to trigger the movement of all DPs in its local c-command domain to its projected specifier positions. In cases where v does not locally c-command any DP, the requirement is trivially satisfied. I show how this accounts for the observed VSO/VOS word order alternations in Samoan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

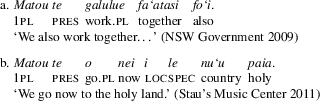

Data in this paper comes from a variety of sources. Examples without an identified source come from consultations with native speakers. Abbreviations of sources in example sentences are as follows: BFP = Brighter Futures Program brochure (NSW Government 2007); BOM = Book of Mormon (1965), The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (1903 Samoan translation); DIfP = Drug Information for Parents brochure (State of Victoria 2003); MH = Mosel and Hovdhaugen (1992); Mi = Milner (1966); Mos = Mosel (2004); Moy = Moyle (1981), ‘O Sina ma le ‘Ulafala (University of Auckland: Libraries and Learning Services 2016); MS = Mosel and So‘o (1997).

In some cases, glosses have been changed from the original for consistency. Orthography also differs from source to source: some sources omit macrons which mark vowel length and the ‘ character which is used for the glottal stop. Where omitted in the source material, these have been added to the examples in this paper.

Abbreviations used are as follows: abs absolutive; caus causative; cia verbal suffix -Cia; comp complementizer; dat dative; dir directional particle; emph emphatic particle; erg ergative; exc exclusive (1st person dual/plural); foc topic/focus marker; fut future; gen genitive; ina verbal suffix -a/-ina; loc locative; neg negation; nspec non-specific determiner; perf perfect; pl plural; pres present tense; q question particle; sg singular; spec specific determiner.

Consultation with native speakers took place between 2013–2014 in Sydney, Australia, Stanford, CA, and Palo Alto, CA. The speakers Emily Sataua and Joey Zodiacal speak the American Samoa variety of Samoan, while Vince Schwenke-Enoka and Fautua Tuamasaga Falefa speak the Samoa variety of Samoan. The extent and nature of dialect variation in Samoan remains an underexplored issue.

Though see Calhoun (2015), which finds that VOS with full DP arguments is rarely used by experimental participants.

If the TAM marker is the present tense marker e, the presence of a subject pronoun causes e to be realized as its allomorph te, and the subject pronoun appears to the left of the TAM marker, instead of to the right.

A possible analysis of the affirmative (11a–b) clauses takes the TAM marker to delete under adjacency with the particle ‘o, adjacency which is interrupted by the negative particle in a negative clause, though further investigation is required. See Chung and Ladusaw (2004:62–65) for a discussion of a similar phenomenon in Māori equational clauses, in which a TAM marker deletes when adjacent to the DP predicate.

Massam (2001) also describes a variety of PNI in Niuean in which a bare NP is adjacent to the existential predicate, forming an existential clause. Samoan lacks this variety of PNI. Existentials are formed as in (9c). A third variety of PNI in Niuean involves the incorporation of bare NPs which are interpreted as thematic instrumental arguments. Samoan also seems to lack these.

The presence of bare NP objects in Samoan does not exclude the possibility that Samoan may also demonstrate morphological incorporation. Chung and Ladusaw (2004) argue that the two modes of incorporation may coexist with reference to Niuean and Māori. See also Baker (2014) for the suggestion that PNI and morphological incorporation of V and N work in tandem in Sakha and Tamil.

In fact, if we find evidence that the constituents labeled VP and vP in (21) are more syntactically complex then sketched, then there will be multiple regions of adjunction sites for modifiers. See Massam (2013) who suggests that strict ordering of adverbials in Niuean is suggestive of a cartographic approach to adverbial modification in the style of Cinque (1999).

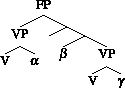

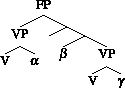

How is it ensured that the correct copy of the object DP is pronounced? (22) is a schema for the VP-fronting account of VSO, where α, β, and γ stand in for copies of the object DP. How do we ensure that only β is pronounced, and not α or γ (generating incorrect word orders)? A basic premise is that constituents which are asymmetrically c-commanded by copies are not pronounced (subject to cross linguistic variation Bobaljik 2002). This is enough to ensure that γ is not pronounced, as it is c-commanded by β. But neither α nor β are c-commanded by copies, leaving α ostensibly able to be pronounced.

-

(22)

The following rule for the pronunciation of sequences of copies draws from Nunes (2004) and Bošković and Nunes (2007), based on an intuition in Chomsky (1995) that elements of a chain are distinguished by their local syntactic environments, i.e., the syntactic category of their sister nodes. According to this intuition, operations apply equally to elements of a chain which have the structurally identical sister nodes.

-

(23)

Non-pronunciation:

-

i.

Do not pronounce A if there is a B which asymmetrically c-commands A and is a copy of B.

-

ii.

If (i) applies to Y whose syntactic sister is Z, delete all copies of Y whose syntactic sister is a copy of Z.

-

i.

In (22), γ is not pronounced by (i), being c-commanded by β. α is not pronounced by (ii). As (i) applies to γ, and its syntactic sister is V, (ii) must apply to α, whose syntactic sister is a copy of V.

-

(22)

Under this paper’s analysis, the phonologically null v head is always stranded clause-finally. As the paper posits that all v heads are silent, it remains unclear how to empirically justify this claim without a clear hypothesis about which morphemes can be conclusively said to instantiate v. A potential candidate for overt v heads are the -ina and -Cia suffixes appearing on derived transitive verbs and transitive verbs with extracted subjects.

It remains to be determined as to how to analyze these suffixes morphosyntactically, though one option could be v-to-V head lowering. This is not precluded by the current analysis, so long as the fronted VP contains the morphological concatenation of v and V. Another option could be to adopt a more complex extended verbal projection, consisting of both Voice and v layers, along the lines of Harley (2013), Legate (2014). Under this analysis, -ina and -Cia could instantiate the v head, and the more complex vP undergoes predicate fronting. Under this analysis, it is the null Voice head that is always stranded clause finally. A deeper exploration of these issues remains a topic for future research.

For a detailed discussion and description of the varieties of complex predication in Samoan, see Mosel (2004).

Though see Toivonen (2000) who analyzes adverbial XPs as directly branching from the V head. Under this account, the V could undergo head movement, with adjoined adverbials in tow. The proposal in this paper derives the same facts without violating common phrase structural assumptions, namely, that XP-sized constituents adjoin at maximal projections.

Massam’s (2010, 2013) analysis of complex predication in Niuean reaches a similar conclusion to the one outlined so far for Samoan in this section. For Massam, VP-fronting in Niuean is evidenced by the pre-subject placement of adverbial modifiers. Her analysis follows Cinque’s (1999) universal hierarchy of functional projections, proposing that post-verbal adverbials in Niuean match Cinque’s ordering for adverbials, except in the inverse order. Massam derives this ordering by positing cyclic “roll-up” movement of these functional projections. The present account of Samoan is neutral as to whether the ordering of relevant adverbial modifiers motivate an analysis in the style of Cinque. The relevant observation is that the fronted predicate can be syntactically complex. I leave the issue of whether the internal structure of the constituent here labeled as VP should be further syntactically decomposed.

A careful comparison between Samoan adverbial placement and Massam’s observations about Niuean remain to be carried out, though certain differences are immediately apparent which may suggest that the analysis of Samoan should be somewhat different to Massam’s. For example, Samoan lacks Niuean’s instrumental applicative construction. While both Niuean and Samoan have a phrase-final question particle, the distribution of Samoan’s question particle, ‘ea, suggests it is attached phrase-finally in the prosodic structure rather than syntactic structure (see Mosel and Hovdhaugen 1992:485).

Wurmbrand (2015) suggests restructuring predicates in some Austronesian languages select for a vP headed by a agent-less v. This alternative account can be adopted without any adverse effects for the VP-movement account.

See Clemens (2014) for an account of restructuring predicates in Niuean assuming head movement. Under her account, the main verb and restructuring verb form a complex head which head-moves to a position higher than the subject. Extending this analysis to Samoan forces us to say that complex predicates such as (40c) consist of a single X0-sized constituent.

Clause (a) ensures that the phase is defined as a maximal projection (CP, DP, vP), however, only the complement of the phase-head is inadmissible to higher operations (by clause (b)), specifiers and adjuncts are able to enter into syntactic dependencies with higher operators (as per Chomsky 1999, 2001). Clause (c) may be an incomplete list of lexical categories which trigger this kind of syntactic barrier. Furthermore, clause (c) may be subject to cross-linguistic variation.

Even though in a VP-fronting structure, the VP does front across the phase head v, this is permitted, as the complement of a phase-head itself is able to enter into syntactic dependencies. Only material properly contained within the phase-head’s complement is inadmissible.

This analysis has its roots in Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou (1998), who posit a similar parameter, although in their system, T’s features may be satisfied by head movement of the verb, rather than phrasal movement. See also Massam and Smallwood (1997) and Davies and Dubinsky (2001) for similar proposals.

In fact, Otsuka’s analysis involves V-to-T-to-C movement, contra the VP-fronting account in this paper.

I use the term ‘weak pronoun’ to distinguish pre-verbal subject pronouns from post-verbal, case-marked pronouns. I remain neutral as to whether subject pronouns in Samoan are better analyzed as clitics or weak pronouns in the sense of Cardinaletti and Starke (1999), leaving this issue as a topic for future research.

There is a worry that T-to-C movement does not fall within the definition of copying in (16), as the movement is not to a specifier position, and the higher copy does not c-command the lower copy. I leave open the question of how head movement is incorporated into the copy theory of movement within this paper, though I suggest it could be insightful to adopt Matushansky’s (2006) proposal that head movement is in fact movement to a specifier position, followed by morphological concatenation of the dislocated head to the attracting head during the linearization procedure via m-merger (cf. the formulation in Harizanov 2014b, 2014a).

Alternatively, negation may head its own projection which selects for FP as its complement, giving the finer grained structure \([_{\mathit{TP}} T\ [_{\mathit{NegP}} \mathit{Neg}\ [_{\mathit{FP}} F\ {...} ] ] ]\). I leave the choice between these two approaches as an open issue.

The scopal argument against the structure in (65) assumes that negation itself cannot take exceptional scope above an indefinite subject. Alternative accounts do not make this assumption. See, e.g., Barker and Shan (2014:90), who provide a lexical semantics for negation which can take exceptional scope. However, an analysis with such scopal flexibility must explain why negation always scopes above indefinite subjects. This fixed scopal ordering is accounted for under the analysis in (66) assuming the scope of indefinites headed by se is invariable.

Under this account, verb initiality in Samoan is derived by two independent factors: fronting of the predicate, and the lack of subject movement to Spec,TP. As two different functional heads are responsible for these properties, this system allows for the possibility of a language which has predicate fronting to the specifier of a lower functional head than T, and then subject raising (of both pronouns and full DPs) to Spec,TP, deriving SVO word order. Chung (2008) considers but rejects a similar hypothesis for the clause structure of Bahasa Indonesia.

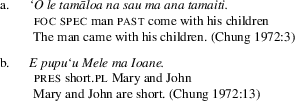

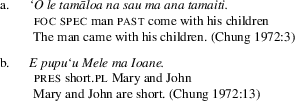

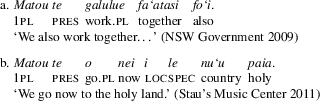

This discussion refers to examples which employ the particle ma. ma doubles as both a conjunction and a comitative preposition in Samoan. Its latter use is exemplified in (32a). However Chung (1972) argues that ma has uses in Samoan which unambiguously show properties of conjunction, as in (32b), in which a conjoined subject triggers plural agreement. Chung (1972) also observes (pace Grinder 1969) that conjunctions with ma in Samoan trigger the Coordinate Structure Constraint.

-

(i)

-

(i)

A question arises as to whether unaccusative and unergative verbs are truly of the same lexical category. If they are of different lexical categories, they may head different constituent types, accounting for their inability to coordinate. The evidence in (79)–(83) below shows that both kinds of predicates are able to causativize using the same range of prefixes. Further, both are able to be marked with number agreement, suggesting they are of the same lexical category.

-

(77)

-

(77)

Ko and Sohn (to appear) discuss a comparable coordination constraint in Korean serial verb constructions (SVCs), where verbs assigning an agent theta-role may only serialize with other verbs assigning an agent theta-role. Unaccusative and passive verbs, which do not assign an agent theta-role, may only serialize with other unaccusative and passive verbs. Their syntactic analysis of SVCs does not involve coordination, so the CSC is inapplicable. They stipulate a constraint on SVCs ensuring that only vs with matching thematic properties may serialize. Although the Korean and Samoan facts differ somewhat (in Korean, unergatives and transitives may serialize, but not in Samoan), an important avenue of investigation should be to what extent constraints on serialization and coordination cross-linguistically can reduce to the same set of principles.

Thanks to an anonymous WCCFL reviewer for suggesting an example of this type.

It is possible that the case marking labeled in (91) as dative is in fact a preposition. Under this alternative analysis, the dative preposition selects for the DP in its complement: [ PP P [ DP D NP ]]. If this view is taken, I suggest that v attracts the DP to its specifier position, and the preposition is “pied-piped” along with the DP to the higher position. Samoan in general lacks preposition-stranding, and so may independently require a pied-piping mechanism to handle cases of movement of DPs embedded within PPs. Deciding between the PP analysis and the DP analysis in (91) is a topic for future research.

The distinction between conditional and unconditional features does not correspond to the distinction between weak and strong features in previous work. These terms have previously applied to optionally vs. obligatorily satisfied features, or features which apply in the narrow syntax vs. covert syntax. Neither of these notions corresponds to the distinction I make here.

A discrepancy between v heads is whether they select for an external argument (transitives, unergatives, pseudo incorporation structures) or not (unaccusatives). See Collins (2015) for a discussion of this discrepancy and how it bears on issues of argument structure and case assignment in Samoan.

See (Urk and Richards 2015: Sect. 2.2), who also posit an EPP feature on v in order to capture intricate word order facts in the Nilotic language Dinka. As in Samoan, the EPP feature on Dinka v may fail to attract any DP in unergative structures. Van Urk and Richards argue that the Dinka EPP on v only attracts DPs to which v has assigned Case, correctly excluding the possibility that (subcategorized and non-subcategorized) locatives raise to Spec,vP. As we have seen in Sect. 7.1, the same cannot be said of Samoan EPP on v, which triggers the movement of (subcategorized and non-subcategorized) inherently Case marked DPs/PPs (91). For this reason, I argue that the EPP feature on Samoan v is always ‘active’, indiscriminately triggering the movement of phrases to which it has assigned Case and those which it has not.

A further difference between the Samoan and Dinka EPP on v is evident when we look at structures with multiple DPs in the c-command domain of v. As I argue in Sect. 7.3, in Samoan, all DPs evacuate the VP constituent to raise to the higher position. In contrast, where the Dinka v c-commands two DPs in a double object construction, just one DP may move. Van Urk and Richards (2015:fn26) propose that v assigns Case to both DPs, and v triggers the movement of exactly one DP to which it assigns Case. I propose Samoan v is more permissive, triggering multiple evacuation of DPs regardless of their source of Case.

Though see Koster (1978), Alrenga (2005), for arguments that subject CPs in English are structurally higher than Spec,TP, which is filled by a null pronoun, in which case the EPP requirement of English TPs is universally satisfied by DPs. An interesting avenue of inquiry is to investigate whether Samoan CP and DP objects occupy the same structural position, and if not, whether the Koster-Alrenga analysis can be extended to the domain of Samoan objects.

An open question is whether the multiple specifiers are subject to any ordering constraints. Following previous work on multiple wh-fronting (e.g., Richards 1997; Bošković 2002), the relative order of moved constituents should be maintained post-movement. The rule in (106) must be refined in order to incorporate this insight, however thorough investigation of the facts in Samoan remains to be undertaken.

References

Aldridge, Edith. 2002. Nominalization and wh-movement in Seediq and Tagalog. Language and Linguistics 3(2): 393–426.

Aldridge, Edith. 2004. Ergativity and word order in Austronesian languages. PhD diss., Cornell University.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1998. Parameterizing AGR: Word order, V-movement and EPP-checking. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16(3): 491–539.

Alrenga, Peter. 2005. A sentential subject asymmetry in English and its implications for complement selection. Syntax 8(3): 175–207.

Baker, Mark C. 1997. Thematic roles and syntactic structure. In Elements of grammar: Handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 73–137. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Baker, Mark C. 2014. Pseudo noun incorporation as covert noun incorporation: Linearization and crosslinguistic variation. Language and Linguistics 15(1): 5–46.

Ball, Douglas. 2008. Clause structure and argument realization in Tongan. PhD diss., Stanford University.

Barker, Chris, and Chung-Chieh Shan. 2014. Continuations and natural language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bauer, Winifred, William Parker, and Te Kareongawai Evans. 1997. The Reed reference grammar of Māori. Auckland: Reed Books.

Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 2002. A-chains at the PF-interface: Copies and covert movement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 20(2): 197–267.

Bošković, Željko. 2002. On multiple wh-fronting. Linguistic Inquiry 33(3): 351–383.

Bošković, Željko, and Jairo Nunes. 2007. The copy theory of movement. In The copy theory of movement, eds. Norman Corver and Jairo Nunes, Vol. 107, 13–74. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Broschart, Jürgen. 1997. Why Tongan does it differently: Categorial distinctions in a language without nouns and verbs. Linguistic Typology 1(2): 123–166.

Burzio, Luigi. 1986. Italian syntax: A government-binding approach. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Cable, Seth. 2012. The optionality of movement and EPP in Dholuo. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 30(3): 651–697.

Calhoun, Sasha. 2015. The interaction of prosody and syntax in Samoan focus marking. Lingua 165: 205–229.

Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency: A case study of the three classes of pronouns. In Clitics in the languages of Europe, ed. Henk van Riemsdijk, 145–233. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Carnie, Andrew Hay. 1995. Non-verbal predication and head-movement. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Carrier, Jill, and Janet H. Randall. 1992. The argument structure and syntactic structure of resultatives. Linguistic Inquiry 23(2): 173–234.

Chapin, Paul G. 1970. Samoan pronominalization. Language 46: 366–378.

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1999. Derivation by phase. In MIT occasional papers in linguistics, Vol. 18. Cambridge: MIT, Department of Linguistics.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In MIT occasional papers in linguistics, Vol. 20. Cambridge: MIT, Department of Linguistics.

Chung, Sandra. 1972. On conjunct splitting in Samoan. Linguistic Inquiry 3(4): 510–516.

Chung, Sandra. 1978. Case marking and grammatical relations in Polynesian. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Chung, Sandra. 1998. The design of agreement: Evidence from Chamorro. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chung, Sandra. 2005. What fronts: On the VP raising account of verb-initial order. In Verb-first: On the ordering of verb-initial languages, eds. Andrew Carnie, Heidi Harley, and Sheila Ann Dooley, 9–30. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Chung, Sandra. 2006. Properties of VOS languages. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 685–720. Malden: Blackwell.

Chung, Sandra. 2008. Indonesian clause structure from an Austronesian perspective. Lingua 118(10): 1554–1582.

Chung, Sandra, and William Ladusaw. 2004. Restriction and saturation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clemens, Lauren Eby. 2014. Prosodic noun incorporation and verb-initial syntax. PhD diss., Harvard University.

Clemens, Lauren Eby, and Maria Polinsky. to appear. VSO and VOS word order, primarily in Austronesian and Mayan languages, In The companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 2nd edn. Hoboken: Wiley–Blackwell.

Cole, Peter, and Gabriella Hermon. 2008. VP raising in a VOS language. Syntax 11(2): 144–197.

Collins, James N. 2014. The distribution of unmarked cases in Samoan. In Argument realisations and related constructions in Austronesian languages. Papers from the 12th International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, eds. I. Wayan Arka and N. L. K. Mas Indrawati, vol. 2, 93–110. Asia-Pacific Linguistics.

Collins, James N. 2015. Samoan nominalization and ergativity. Ms., Stanford University.

Collins, James N. to appear. Pseudo noun incorporation in discourse. In Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA) 20, ed. Joey Sabbagh.

Davies, William D, and Stanley Dubinsky. 2001. Remarks on grammatical functions in transformational syntax. In Objects and other subjects, 1–19. Berlin: Springer.

Davis, Henry. 2005. Coordination and constituency in St’át’imcets (Lillooet Salish). In Verb first: On the syntax of verb-initial languages, eds. Andrew Hay Carnie, Heidi Harley, and Sheila Ann Dooley, 31–64. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Deal, Amy Rose. 2009. The origin and content of expletives: Evidence from “selection”. Syntax 12(4): 285–323.

Dikken, Marcel den. 1995. Particles: On the syntax of verb-particle, triadic, and causative constructions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Emonds, Joseph. 1972. Evidence that indirect object movement is a structure-preserving rule. Foundations of Language 8(4): 546–561.

Emonds, Joseph E. 1976. A transformational approach to English syntax: Root, structure-preserving, and local transformations. New York: Academic Press.

Gazdar, Gerald. 1981. Unbounded dependencies and coordinate structure. Linguistic Inquiry 12(2): 155–184.

Gribanova, Vera. 2009. Structural adjacency and the typology of interrogative interpretations. Linguistic Inquiry 40(1): 133–154.

Grinder, John T. 1969. Conjunct splitting in Samoan. University of California at San Diego, Department of Linguistics.

Harizanov, Boris. 2014a. Clitic doubling at the syntax-morphophonology interface. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32(4): 1033–1088.

Harizanov, Boris. 2014b. On the mapping from syntax to morphophonology. PhD diss., UC Santa Cruz.

Harley, Heidi. 2010. Affixation and the Mirror Principle. In Interfaces in linguistics, eds. Raffaella Folli and Christiane Ullbricht, 166–186. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harley, Heidi. 2013. External arguments and the Mirror Principle: On the distinctness of Voice and v. Lingua 125: 34–57.

Harley, Heidi. to appear. Getting morphemes in order: Merger, affixation and head-movement. In Diagnosing syntax, eds. Lisa Cheng and Norbert Cover. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harley, Heidi, and Rolf Noyer. 1998. Mixed nominalizations, short verb movement and object shift in English. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 28, 143–157.

Heim, Irene, and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hoekstra, Teun. 1988. Small clause results. Lingua 74(2): 101–139.

Hohaus, Vera, and Anna Howell. 2015. Alternative semantics for focus and questions: Evidence from Samoan. In Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA) XXI, eds. A. Camp et al.

Hohepa, Patrick W. 1969. Not in English and kore and eehara in Māori. Te Reo 12: 1–34.

Johnson, Kyle. 1991. Object positions. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 9(4): 577–636.

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ko, Heejeong, and Daeyong Sohn. to appear. Decomposing complex serialization: The role of v. Korean Linguistics.

Koizumi, Masatoshi. 1993. Object agreement phrases and the split VP hypothesis. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 18: 99–148.

Koster, Jan. 1978. Conditions, empty nodes, and markedness. Linguistic Inquiry.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2005. Building resultatives. In Events in syntax, semantics, and discourse, eds. Claudia Maienbaum and Angelke Wollstein-Leisen, 177–212. Tubingen: Niemeyer.

Langacker, Ronald W. 1969. On pronominalization and the chain of command. In Modern studies in English, eds. David A. Reibel and Sanford A. Schane, 160–186. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Lee, Felicia. 2000. VP remnant movement and VSO in Quiavini Zapotec. In The syntax of verb initial languages, 143–162. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2003. Some interface properties of the phase. Linguistic Inquiry 34(3): 506–515.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2008. Morphological and abstract case. Linguistic Inquiry 39(1): 55–101.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2014. Voice and v: Lessons from Acehnese. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Levin, Beth, and Malka Rappaport Hovav. 1995. Unaccusativity: At the syntax-lexical semantics interface. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Levinson, Lisa. 2010. Arguments for pseudo-resultative predicates. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 28(1): 135–182.

Massam, Diane. 2000. VSO and VOS: Aspects of Niuean word order. In The syntax of verb initial languages, eds. Andrew Carnie and Eithne Guilfoyle, 97–116. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Massam, Diane. 2001. Pseudo noun incorporation in Niuean. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19(1): 153–197.

Massam, Diane. 2005. Lexical categories, lack of inflection, and predicate fronting in Niuean. In Verb-first: On the ordering of verb-initial languages, eds. Andrew Carnie, Heidi Harley, and Sheila Ann Dooley, 227–242. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Massam, Diane. 2010. Deriving inverse order: The issue of arguments. In Austronesian and theoretical linguistics, eds. Raphael Mercado et al., 271–296. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Massam, Diane. 2013. Nuclear complex predicates in Niuean. Lingua 135: 56–80.

Massam, Diane, and Carolyn Smallwood. 1997. Essential features of predication in English and Niuean. In North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 27, ed. Kiyomi Kusumoto, 263–272. University of Massachusetts, Amherst: GLSA.

Matushansky, Ora. 2006. Head movement in linguistic theory. Linguistic Inquiry 37(1): 69–109.

McCloskey, James. 2000. Quantifier float and wh-movement in an Irish English. Linguistic Inquiry 31(1): 57–84.

Medeiros, David J. 2013. Hawaiian VP-remnant movement: A cyclic linearization approach. Lingua 127: 72–97.

Mercado, Raphael. 2002. Verb raising and restructuring in Tagalog. Master’s thesis, University of Toronto.

Milner, George Bertram. 1966. Samoan dictionary. Auckland: Polynesian Press.

Mosel, Ulrike. 2004. Complex predicates and juxtapositional constructions in Samoan. In Empirical approaches to language typology, 263–296. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Mosel, Ulrike, and Even Hovdhaugen. 1992. Samoan reference grammar. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

Mosel, Ulrike, and Ainslie So‘o. 1997. Say it in Samoan. Pacific Linguistics.

Neeleman, Ad, and Fred Weerman. 1993. The balance between syntax and morphology: Dutch particles and resultatives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 11(3): 433–475.

NSW Government. 2007. Faamatalaga mo Matua. http://www.community.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/321111/brighterfutures_samoan.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2016.

NSW Government. 2009. E faapefea ona matou fesoasoani. www.community.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/321247/hwh_samoan.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2016.

Nunes, Jairo. 2004. Linearization of chains and sideward movement. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Otsuka, Yuko. 2005. Two derivations of VSO: A comparative study of Niuean and Tongan. In Verb first: On the syntax of verb-initial languages, eds. Andrew Carnie, Heidi Harley, and Sheila Ann Dooley, 65–90. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Pearce, Elizabeth. 2002. VP versus V raising in Māori. In Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA) 8, eds. Andrea Rackowski and Norvin Richards, 225–240. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Pearson, Matthew. 2000. The clause structure of Malagasy: A minimalist approach. PhD diss., UCLA.

Pearson, Matthew. 2007. Predicate fronting and constituent order in Malagasy. Ms., Reed College.

Pearson, Matthew. 2013. Predicate raising and perception verb complements in Malagasy. Ms., Reed College.

Perlmutter, David M. 1978. Impersonal passives and the unaccusative hypothesis. In Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS) 4, 157–189. Berkeley.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1989. Verb movement, universal grammar, and the structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry.

Preminger, Omer. 2011. Agreement as a fallible operation. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and its failures, Vol. 68. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rackowski, Andrea, and Lisa Travis. 2000. V-initial languages: X or XP movement and adverbial placement. In The syntax of verb initial languages, eds. Andrew Carnie and Eithne Guilfoyle, 117–141. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ramchand, Gillian, and Peter Svenonius. 2002. The lexical syntax and lexical semantics of the verb-particle construction. In West coast conference on formal linguistics (WCCFL) 21, 387–400.

Richards, Norvin. 1997. What moves where when in which language? PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Richards, Norvin. 2001. Movement in language: Interactions and architectures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rijkhoff, Jan. 2003. When can a language have nouns and verbs? Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 35(1): 7–38.

Roberts, Ian. 1988. Predicative APs. Linguistic Inquiry 19(4): 703–710.

Ross, John Robert. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Rudin, Catherine. 1988. On multiple questions and multiple wh-fronting. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 6(4): 445–501.

Samoa, Huko. 2015. Afamasagaofisa. https://afamasagaofisa.wordpress.com/. Accessed April 7, 2016.

Seiter, William J. 1980. Studies in Niuean syntax. New York: Garland Publishing.

Simpson, Jane. 1983. Resultatives. In Papers in Lexical-functional grammar, eds. Lori Levin, Malka Rappaport, and Annie Zaenen, 143–157. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Son, Minjeong, and Peter Svenonius. 2008. Microparameters of cross-linguistic variation: Directed motion and resultatives. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 27, eds. Natasha Abner and Jason Bishop, 388–396. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Sorace, Antonella. 2000. Gradients in auxiliary selection with intransitive verbs. Language 76(4): 859–890.

State of Victoria. 2003. Faamatalaga mo Matua i Fualaau. http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/health/samoan.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2016.

Stau’s Music Center. 2011. Matou Te O Nei Ile Nu’u Paia. www.youtube.com/watch?v=C3EuLVRW7vQ. Accessed April 7, 2016.

Svenonius, Peter. 2002. Subjects, expletives, and the EPP. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Toivonen, Ida. 2000. The morphsyntax of Finnish possessives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 18(3): 579–609.

University of Auckland: Libraries and Learning Services. 2016. ‘O Sina ma le ‘Ulafala. http://www.fagogo.auckland.ac.nz/content.html?id=1. Accessed April 7, 2016.

Urk, Coppe van, and Norvin Richards. 2015. Two components of long-distance extraction: Successive cyclicity in Dinka. Linguistic Inquiry 46: 113–155.

Wechsler, Stephen. 1998. Resultative predicates and control. In Texas linguistic forum, Vol. 38, 307–322.

Wurmbrand, Susi. 2001. Infinititives: Restructing and clause structure. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Wurmbrand, Susi. 2015. Complex predicate formation via voice incorporation. In Approaches to complex predicates, eds. Léa Nash and Pollet Samvelian, 248–290. Leiden: Brill. Ms., University of Connecticut.

Yu, Kristine M. 2011. The sound of ergativity: Morphosyntax-prosody mapping in Samoan. In North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 39, eds. Suzi Lima, Kevin Mullin, and Brian Smith, 825–838. Amherst: Graduate Linguistic Student Association.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Emily Sataua, Joey Zodiacal, Vince Schwenke-Enoka, and Fautua Tuamasaga Falefa for their time as native speaker consultants. Thanks also to Rajesh Bhatt, Dylan Bumford, William Foley, Vera Gribanova, Boris Harizanov, Beth Levin, Line Mikkelsen, Christopher Potts, Kristine Yu, three anonymous reviewers at NLLT and the editor Julie Anne Legate insightful comments. Earlier versions of this work were presented at the 89th Linguistics Society of America annual meeting (2014) and the 32nd West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics at University of Southern California (2014). Thanks to the reviewers and audiences at these conferences for valuable comments. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Collins, J.N. Samoan predicate initial word order and object positions. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 35, 1–59 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9340-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9340-1