Abstract

This study provides a synthesis of corpus-based and experimental investigations of word-order preferences in German infinitival complementation. We carried out a systematic analysis of present-day German corpora to establish frequency distributions of different word-order options: extraposition, intraposition, and ‘third construction’. We then examined, firstly, whether and to what extent corpus frequencies and processing economy constraints can predict the acceptability of these three word-order variants, and whether subject raising and subject control verbs form clearly distinguishable subclasses of infinitive-embedding verbs in terms of their word-order behaviour. Secondly, our study looks into the issue of coherence by comparing acceptability ratings for monoclausal coherent and biclausal incoherent construals of intraposed infinitives, and by examining whether a biclausal incoherent analysis gives rise to local and/or global processing difficulty. Taken together, our results revealed that (i) whilst the extraposition pattern consistently wins out over all other word-order variants for control verbs, neither frequency nor processing-based approaches to word-order variation can account for the acceptability of low-frequency variants, (ii) there is considerable verb-specific variation regarding word-order preferences both between and within the two sets of raising and control verbs under investigation, and (iii) although monoclausal coherent intraposition is rated above biclausal incoherent intraposition, the latter is not any more difficult to process than the former. Our findings indicate that frequency of occurrence and processing-related constraints interact with idiosyncratic lexical properties of individual verbs in determining German speakers’ structural preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 German infinitival complementation

German infinitival complementation provides an intriguing challenge for contemporary linguistic theory as infinitive-embedding verbs and their complements can show considerable variability with respect to their linearization patterns. Infinitival complements can either be placed at the right periphery of the embedding verb, a word-order variant referred to as ‘extraposition’ (1a), they can be intraposed, i.e. placed between complementizer and matrix verb (1b), or they can be split into a discontinuous infinitival construction referred to as the ‘third construction’ (1c) (Haider 2010).

(1) | a. | extraposition | ||||||

dass | Fred | versucht | [den | Hund | zu | streicheln] | ||

that | Fred | tries | the | dog | to | pet | ||

b. | intraposition | |||||||

dass | Fred | [den | Hund | zu | streicheln] | versucht | ||

that | Fred | the | dog | to | pet | tries | ||

c. | third construction | |||||||

dass | Fred | [den | Hund] | versucht | [zu | streicheln] | ||

that | Fred | the | dog | tries | to | pet | ||

‘that Fred tries to pet the dog' | ||||||||

Intraposed infinitives as in (1b) were first recognized as potentially ambiguous by Bech (1955), who noted that some verbs build a single clausal domain with their infinitival complement while others select infinitives that form a clausal domain independent of the governing predicate. Bech (1955) refers to these two infinitive types as ‘coherent’ (i.e., monoclausal) and ‘incoherent’ (i.e., biclausal) infinitival constructions, respectively.Footnote 1 In more recent work, incoherently construed infinitives are usually assumed to be CP constituents as shown in (2a), whereas coherent infinitives are thought to build a verbal complex with the matrix verb as indicated in (2b).

(2) | a. | dass | Fred | [CP | PRO | den | Hund | zu | streicheln] | versucht |

b. | dass | Fred | den | Hund | [VP | zu | streicheln | versucht] | ||

that | Fred | the | dog | to | pet | tries | ||||

‘that Fred tries to pet the dog' | ||||||||||

Despite extensive discussion of these syntactic variation patterns in formal linguistic theory (Haider 2010; Reis 2001; Wurmbrand 2001, among others), complemented by findings from a small number of experimental studies (Bayer et al. 2005; Schmid et al. 2005; Bader and Schmid 2009; Bosch et al. 2022), the factors influencing speakers' preferences for individual syntactic variants are not yet fully understood. Factors which may lead speakers or writers to choose one variant over another include lexical properties of individual verbs or verb classes, the frequency of occurrence of individual linearization patterns, and processing-related factors.

The current study investigates how the frequency distributions of different word-order patterns relate to these patterns' perceived acceptability, and whether German speakers' previously reported preference for a coherent construal of intraposed infinitives can be attributed to processing-related factors. Additionally, our study contributes to the discussion of whether subject raising and control verbs can be divided into clearly distinct subgroups according to their word-order behaviour, as has been proposed within formal linguistic theory (e.g., Reis 2001; Wurmbrand 2001; Haider 2010).

Following a brief review of the theoretical and experimental literature, we will report the results from (i) a synchronic corpus study of present-day German seeking to establish the frequency distributions of different word-order patterns, (ii) two acceptability judgement experiments to assess the degree to which German speakers accept different word-order variants and coherent versus incoherent construals, and (iii) a self-paced reading experiment examining the processing of intraposed infinitival complements.

2 Theoretical and empirical approaches to German infinitival complementation

2.1 Usage-based approaches

One possible approach to word-order variation is represented by usage-based frameworks, which argue that frequency of occurrence determines language performance and representation (e.g., Bybee 2006; Bybee and Beckner 2010). Bybee (2010), for example, regards properties of languages and their grammars as emergent from the frequency of input and the way the human language faculty deals with the experience of language use (e.g., Ellis and Larsen-Freeman 2006). With respect to word-order variation, usage-based approaches to language performance would expect language users’ acceptability of alternative syntactic variants to be determined their frequency distributions across the language.

Newmeyer (2003), in contrast, argues that language performance and representation are not predictable from usage-based facts about language. Although he acknowledges the value of statistical information for the investigation of language variation, use, and change, he points out that “it is a long way from there [corpus-based frequency analyses—authors’ note] to the conclusion that corpus-derived statistical information is relevant to the nature of the grammar of any individual speaker” (695). Accordingly, Newmeyer (2003) believes that infrequent or generally dispreferred structures may be part of speakers’ grammatical representations as ‘latent’ structures and may thus be judged as acceptable even though they are rarely used or attested in corpora.

Many previous studies have combined synchronic corpus analyses with experimental methods such as acceptability judgements to test predictions derived from usage-based accounts (e.g., Gries et al. 2005; Schmid et al. 2005; Kempen and Harbusch 2008; Baroni et al. 2009; Adli 2011; Radford et al. 2012; Ford and Bresnan 2013). Interestingly, several of these studies observed imperfect correlations between corpus probabilities and rating patterns: Highly acceptable alternatives predominate corpus frequencies, while less acceptable variants might not be attested in corpus data at all (Featherston 2005; Kempen and Harbusch 2005; Bader and Häussler 2010). Also, patterns which are rarely used may nevertheless elicit relatively high acceptability scores, a finding that is in line with Newmeyer’s (2003) proposal.

In order to assess frequency distributions and speakers’ acceptance of different word-order variants in German infinitival complementation, Bayer et al. (2005) conducted a multi-methodological study that included a corpus search and an acceptability rating experiment. Their search of the Mannheim COSMAS corpus of newspaper texts and literature found extraposed infinitives to be much more frequent than intraposed ones: Less than 4% of infinitival complements occurred in an intraposed position, and less than 20% of all verbs in the sample of control verbs they examined occurred with an intraposed infinitive. These findings were taken to indicate that intraposition represents a marked (although grammatical) option. In contrast, the acceptability rating data revealed that subject control verbs with infinitival complements functioning as direct objects elicited fairly favourable ratings for intraposition (a mean rating of 2.1 on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 meaning ‘acceptable’ and 5 meaning ‘unacceptable’). This imperfect correlation between corpus data and experimental findings suggests that frequency of occurrence alone cannot predict acceptability, particularly with respect to infrequent word-order patterns. However, note that Bayer et al. (2005) only considered two of the three possible word-order variants, and their frequency data was not systematically related to their judgement data on a per-verb basis.

Also combining corpus search and experimentation, Bosch et al. (2022) additionally included the third construction (1c) in their investigations. Focusing on a small set of control verbs, we compared the frequency of occurrence of the three linearization patterns with German speakers' scalar acceptability judgements for each individual verb. Again, an imperfect alignment was observed between frequency counts and acceptability ratings, with high-frequency patterns matching corpus probabilities but low-frequency patterns sometimes being judged as more acceptable than their statistical distribution would have suggested. Both Bayer et al. (2005) and Bosch et al. (2022) found that the extraposition pattern was the most frequently attested one and also elicited the most favourable acceptability ratings.

The present study builds on and extends the above investigations by carrying out a large-scale corpus search covering different corpora and genres, by additionally including a set of subject raising verbs to examine whether these do indeed differ categorically from subject control verbs with regard to their word-order behaviour and coherence properties and by systematically testing these verbs' word-order preferences across all three variants (extraposition, intraposition, and third construction) for their predictability from frequency distributions.

2.2 Processing-based approaches

Constraints imposed by the language processing system are another factor to take into account when examining the question of why certain syntactic variants are preferred over others. These may include, for example, the avoidance of clausal centre-embedding, a preference for the structurally simplest analysis, ambiguity avoidance, and the minimization of dependency length. From a processing perspective, extraposition should be favoured over other word-order variants as it avoids centre-embedding and does not give rise to any local or global structural ambiguities (compare, e.g., Bader and Schmid 2009). It also helps to keep the distance between the matrix verb and its subject as short as possible. In a spoken production experiment, Bosch et al. (2022) found that extraposition was strongly preferred over all other word-order variants for the control verbs under investigation, corresponding to this pattern's relative corpus frequency.

Regarding intraposition, Bayer et al. (2005) report experimental evidence showing that incoherent construals are dispreferred by speakers of German, a finding that can be accounted for by structural economy constraints: Coherent construals involve less complex syntactic representations than incoherent construals and will thus be an economy-driven parser's preferred analysis choice. Bader and Schmid (2009) note that from the perspective of left-to-right incremental processing, coherently analysed intraposed infinitives avoid two well-known processing problems: the increased processing cost typically associated with clausal centre-embedding, and the need for structural reanalysis due to a clausal boundary that was initially overlooked (1461).

Bader and Schmid (2009) report results from speeded grammaticality judgements showing that intraposed incoherent infinitives are indeed difficult to process in comparison to extraposed infinitives, a finding consistent with what the authors refer to as the Clause-Union Preference Hypothesis. At the same time, however, their results provide evidence in favour of another hypothesis: According to Bader and Schmid's (2009) Verb-Cluster Complexity Hypothesis (VCCH) a coherent analysis incurs more processing cost than an incoherent one at the point where the verb cluster is formed, reflecting the cost associated with argument structure unification. Considering these findings, it would appear that neither a coherent nor an incoherent analysis of intraposed infinitives represents an optimal clausal structure from a processing economy perspective. Both Bayer et al. (2005) and Bader and Schmid (2009) raise the question of why intraposed infinitives exist at all in German, given that extraposition is available as an alternative. Bader and Schmid (2009) suggest that the verb-final property of German is the reason that intraposed infinitives are (still) available.

Note that from a left-to-right processing perspective the VCCH predicts a processing disadvantage for coherently versus incoherently construed infinitives when the verb cluster is encountered but not during earlier parts of the infinitival complement. Collecting end-of-sentence acceptability judgements did not allow Bader and Schmid (2009) to test this prediction directly, however. Their conclusion regarding the VCCH moreover rests on grammaticality judgements of long passive constructions, whose grammatical status is at best controversial. Our Experiment 3 tests the above prediction more directly by using a word-by-word self-paced reading task and different types of stimulus sentences.

Neither of the above studies investigated the acceptability or processing of third constructions, a word-order pattern which involves neither verb cluster formation nor clausal centre-embedding, but which may nevertheless allow for a coherent construal in that no clause boundary needs to be postulated (Wöllstein-Leisten 2001). Comparing whole-sentence reading comprehension times for all three word-order patterns, Bosch et al. (2022) found that intraposed and extraposed infinitival complements were about equally difficult to comprehend and significantly easier to process than third constructions. We argued that third constructions are hard to process because this linearization pattern not only breaks up the dependency between the matrix subject and matrix verb but also the infinitival complement itself, and may additionally create a temporary ambiguity that requires reanalysis. However, as the intraposed infinitives in Bosch et al. (2022) were not disambiguated towards a coherent or incoherent construal, their results do not tell us anything about the relative processing difficulty of coherent versus incoherent infinitives.

2.3 Formal linguistic approaches

The syntactic type of infinitival complement has been argued to limit word-order variation in present-day German. As illustrated by (3a) versus (3b) below, extraposition is assumed to be available only for verbs such as beabsichtigen ‘intend’ that select CP complements (resulting in a biclausal incoherent construal), whilst it is precluded for verbs such as scheinen ‘seem’ that require monoclausal coherent construals.

(3) | a. | weil | Fred | niemals | beabsichtigte | [CP | PRO | seinen | Goldfisch |

because | Fred | never | intented | his | goldfish | ||||

auszusetzen] | |||||||||

to.release | |||||||||

‘because Fred never intended to release his goldfish’ | |||||||||

b. | *weil | Selma | gestern | schien | [einen | Essay | zu | schreiben] | |

because | Selma | yesterday | seemed | an | essay | to | write | ||

‘because Selma seemed to write an essay yesterday’ | |||||||||

Intraposition, on the other hand, allows for the positioning of the infinitival complement in the matrix clause's middle field. If no other material intervenes between the infinitival and matrix verb, intraposed infinitival complements are often ambiguous with respect to coherence, particularly with control verbs, such as versuchen ‘try’, which allow both monoclausal coherent and biclausal incoherent construals, as illustrated in (2) above.

However, intraposition may also yield patterns which unambiguously signal either coherent or incoherent configurations. In (4a) below, for instance, non-verbal material (the adverb niemals ‘never’) intervenes between the infinitive and the matrix verb, thus precluding the formation of a verbal complex and triggering an incoherent structure. The scrambling out of infinitival material into the matrix domain, on the other hand, unambiguously signals a monoclausal structure. A classical diagnostic pattern for this is pronoun fronting as in (4b).

(4) | a. | weil | Fred | [CP | PRO | seinen | Goldfisch | auszusetzen] | niemals |

because | Fred | his | goldfish | to.release | never | ||||

beabsichtigte | |||||||||

intended | |||||||||

‘because Fred never intended to release his goldfish’ | |||||||||

b. | weil | ihni | das | Leben | ti | zu | überholen | drohte | |

because | him.ACC | the | life | to | pass.by | threaten | |||

‘because life threatened to pass him by’ | |||||||||

Other diagnostics for the distinction of monoclausal and biclausal structures include their behaviour with respect to the scope of negation, adverbial modifiers and binding; see Haider (2010, 311) for an exhaustive list of diagnostics with pertinent examples. The status of the third construction pattern is more controversial and has not been studied very extensively with the exception of Wöllstein-Leisten (2001) (for arguments of third constructions as coherent structures see also Reis (2001, 140)).

Traditionally, it has been argued that the distribution of (in-)coherent infinitival constructions is lexically driven. A well-defined group of verbs obligatorily build verbal complexes with the non-finite verb they select, thus requiring the infinitival complement to be intraposed. This class includes, for example, raising verbs such as scheinen ‘seem’ and pflegen ‘be in the habit of’, which do not select an external argument and thus in general do not impose any semantic restrictions on their grammatical subject. Control verbs, in contrast, assign thematic roles to both their external and internal arguments and have been argued to select CP complements, which may either be extraposed (5a) or intraposed (5b).

(5) | a. | weil | Selma | ihm | vorwirft, | [ihren | Goldfisch | vernachlässigt |

because | Selma | him.DAT | reproaches | her | goldfish | neglected | ||

zu | haben] | |||||||

to | have | |||||||

‘because Selma reproaches him for having neglected her goldfish’ | ||||||||

b. | weil | Selma | ihm | [ihren | Goldfisch | vernachlässigt | zu | |

because | Selma | him.DAT | her | goldfish | neglected | to | ||

haben] | vorwirft | |||||||

have | reproaches | |||||||

‘because Selma reproaches him for having neglected her goldfish’ | ||||||||

A subset of control verbs select both clausal and non-clausal infinitival complements, with no construction-specific meaning difference between these two complement types (Haider 2011, 278). Two prominent examples include the subject control verbs versuchen ‘try’ and beschließen ‘decide’. These verbs are traditionally referred to as optionally coherent verbs (Haider 1994) and not only allow for both intraposition (6a) and extraposition (6b) but also for the third construction pattern (6c).Footnote 2

(6) | a. | weil | Fred | diesen | Boxkampf | zu | gewinnen | versucht |

because | Fred | this | fight | to | win | tries | ||

b. | weil | Fred | versucht, | diesen | Boxkampf | zu | gewinnen | |

because | Fred | tries | this | fight | to | win | ||

c. | weil | Fred | diesen | Boxkampf | versucht | zu | gewinnen | |

because | Fred | this | fight | tries | to | win | ||

‘because Fred Tries to win this boxing match' | ||||||||

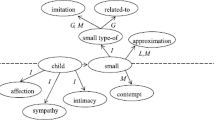

An alternative approach to the classification of infinitive-embedding verbs has been put forward by Wurmbrand (2001) who uses the notion of graded (in-) coherence, distinguishing between four instead of three types of verbs selecting infinitival complements. In her view, control verbs that are transparent for coherence phenomena are not of the same type as raising verbs. Instead she distinguishes between lexical and functional predicates, yielding what she calls lexical restructuring and functional restructuring infinitives, respectively (see Table 1 for an overview of verbal classifications according to Haider (2010) and Wurmbrand (2001)). In functional restructuring contexts, the matrix verb instantiates a functional head (AUX) and the non-finite verb is the main verb, whereas in lexical restructuring contexts the matrix verb is the head of a VP which in turn embeds a non-finite VP complement. Wurmbrand’s (2001) approach differs from Haider's (1994) particularly in the way it accounts for the distribution of third constructions. According to Wurmbrand (2001), non-focus scrambling constructions such as the third construction are unavailable for functional restructuring verbs such as scheinen and pflegen but are available for lexical restructuring verbs such as versuchen. However, while lexical restructuring verbs allow for the third construction as well as pronoun fronting, others prohibit the third construction, constituting the class of reduced non-restructuring verbs, among which she includes, e.g., beschließen. In Wurmbrand’s (2001) view genuinely non-restructuring verbs are those that block any type of coherent structures including pronoun fronting. Typical examples for non-restructuring verbs are factive verbs such as bedauern ‘regret’ and vorwerfen ‘reproach’ (see Table 1).Footnote 3

Another attempt to conceptualize word-order variation in German infinitival complementation as a graded phenomenon was put forward by Grosse (2005). Grosse claims that individual members of infinitive-embedding verbs that are compatible with both coherent and incoherent structures exhibit varying degrees of coherence, and thus allow different word-order variants to varying degrees.

To shed more light on the question of how the set of control verbs allowing monoclausal construals is defined, Schmid et al. (2005) collected judgement data to examine the effects of structural factors such as argument structure and control properties on the acceptability of various types of coherent and non-coherent infinitival constructions for subject and object control verbs. Schmid et al.'s (2005) results revealed substantial verb-specific variation patterns with regard to coherence, with the verb versuchen scoring highest on the authors' coherence scale. Schmid et al. (2005) do not discuss these verb-specific findings any further, however.

None of the above-mentioned experimental studies have considered raising verbs, which in present-day German are assumed to behave homogeneously in permitting coherent intraposed infinitival complements only. The present study focuses on a small set of subject raising and subject control verbs and examines these verbs' word-order behaviour systematically across both corpus and experimental data, including their coherence preferences.

3 The present study

Our study has two main objectives: (i) to test hypotheses derived from usage-based, processing-based and formal linguistic approaches to word-order variation, and (ii) to test the hypothesis that processing economy constraints should disfavour an incoherent construal of intraposed infinitives. Usage-based approaches predict that speakers' preferences for certain word-order variants should be determined by frequency distributions, whilst processing-based approaches predict that certain word-order options or analysis choices should be preferred due to processing economy constraints, other things being equal. Formal approaches make predictions as to what structural patterns a given type of verb should or should not permit.

As a first step, we take a corpus-based perspective on German infinitival complementation and examine how different word-order variants in combination with particular infinitive-embedding verbs are distributed across corpora of present-day German. Our corpus analysis serves to establish frequency distributions of the word-order patterns under investigation and thus provides a baseline for assessing the predictions made by usage-based approaches to language performance and representation.

Secondly, we take an experimental perspective on word-order behaviour in German infinitival complementation by carrying out two untimed acceptability rating tasks and an online self-paced reading task. The acceptability data is then evaluated against our corpus findings, to assess whether and to what extent corpus frequency distributions of the different linearization patterns can predict their acceptability. We also examine the acceptability of monoclausal coherent versus biclausal incoherent construals of intraposed infinitives, to establish a baseline as to whether incoherent word-order patterns are less readily accepted than coherent ones, and to see to what extent the sets of raising and control verbs under investigation behave homogeneously with respect to these linearization patterns. Our reading-time task then builds on that baseline and additionally probes the real-time processing of coherent versus incoherent intraposed infinitival complements of subject control verbs.

The current study focuses on the two prototypical German raising verbs scheinen ‘seem’ and pflegen ‘be in the habit of’, and on the four subject control verbs versuchen ‘try’, beschließen ‘decide’, ankündigen ‘announce’, and bedauern ‘regret’. The latter four verbs share the same control properties and argument structure and differ only in their semantic interpretation: While according to Wurmbrand (2001) ankündigen and bedauern are classified as factive/propositional verbs, versuchen and beschließen represent irrealis verbs.

3.1 The corpus study

In order to establish the frequency distributions of the different word-order variants across our selected verbs, we performed a systematic analysis of the following corpora: a selection of newspaper articles from DeReKo, the German Reference CorpusFootnote 4 (Kupietz et al. 2010), a German Twitter corpusFootnote 5 (Scheffler 2014) and a subcorpus of the DWDS-Kernkorpus 21 including fiction and scientific textsFootnote 6 (Geyken 2007). By including different genres, and in particular a source that, although it contains both curated and spontaneous content, shows an “oral-like” style (Scheffler 2014, 2288), i.e. the Twitter corpus, we aimed at expanding the range of different corpus types in order to obtain a more representative input sample.

The newspaper corpus included articles from the year 2016 including two national newspapers, Die Zeit and Süddeutsche Zeitung, and consisted of 31,236,121 tokens. The Twitter corpus comprised 360,331,744 tokens and the DWDS 4,641,197 tokens. Hence, in total, our corpus comprised 396,209,062 tokens.Footnote 7

3.1.1 Methods

For each corpus we extracted infinitival complements governed by the verbs scheinen, pflegen, versuchen, beschließen, ankündigen, and bedauern in sentences with a closed sentence bracket, that is, either verb final subordinate clauses (7) or main clauses with a complex predicate (8).

(7) | …daß | irgendwer | versucht, | sie | zu | erreichen |

…that | someone | tries | her | to | reach | |

‘…that someone tries to reach her’ | ||||||

(DWDS: Beyer, Spione, 93) | ||||||

(8) | Er | würde | aber | versuchen, | alles | zu | verzögern |

he | would | however | try | everything | to | delay | |

‘However he would try to delay everything’ | |||||||

(DWDS: Kopetzky, GrandTour, 460) | |||||||

The hits were then annotated as to the position of the infinitive as follows:

(9) | a. | extraposition | |||||

Wenn | sie | beschließen, | [die | Dinge | selbst | ||

if | they | decide | the | things | themselves | ||

in | die | Hand | zu | nehmen] | |||

in | the | hand | to | take | |||

‘If they decide to take things into their own hands’ | |||||||

(DeReKo: Z16/FEB.00275 Zeit, 11.02.2016, 58) | |||||||

b. | intraposition | ||||||

Wie | Firmen | [diese | Gemengelage | zu | nutzen] | ||

how | companies | this | hotchpotch | to | use | ||

versuchen | |||||||

try | |||||||

‘How companies try to use this hotchpotch’ | |||||||

(DeReKo: U16/FEB.00930 SZ, 06.02.2016, 57 | |||||||

c. | third | construction | |||||

Dass | die | gegnerischen | Fans | [dich] | versuchen | ||

That | the | opposing | fans | you.ACC | try | ||

[abzulenken] | |||||||

to.distract | |||||||

‘That the opposing fans try to distract you’ | |||||||

(DeReKo: Z16/OKT.00119 Zeit, 06.10.2016, 58) | |||||||

d. | intraposition | coherent | |||||

wie | [ihn] | Ernst | Nolte | 1963 | [zu | ||

as | it.ACC | Ernst | Nolte | 1963 | to | ||

etablieren] | versuchte | ||||||

establish | tried | ||||||

‘As Ernst Nolte in 1963 tried to establish it’ | |||||||

(DeReKo: Z16/SEP.00736 Zeit, 29.09.2016, 53) | |||||||

e. | intraposition | Incoherent | |||||

Er | war | seit | langer | Zeit | der | ||

he | was | since | long.DAT | time | the | ||

erste | Mensch, | den | belogen | zu | |||

first | person | whom | lied.to | to | |||

haben | sie | wirklich | bedauerte. | ||||

have | she | really | regretted | ||||

‘He was he first person in a long time whom she really regretted to have lied to’ | |||||||

(DWDS: Kopetzky, GrandTour, 500) | |||||||

In the case of intraposition, if any evidence for either a coherent or an incoherent structure was found, this was further specified. For example, in case pronoun fronting was attested, intraposition was further annotated as coherent as in (9d). If the intraposed infinitive was not directly adjacent to the matrix verb but interrupted by non-verbal material as in (9e), intraposition was coded as incoherent. Example (9e) represents a case of a ‘pied-piping’ construction in which the infinitival complement directly follows the relative pronoun den ‘whom’ and is located at the left periphery of the relative clause in front of the matrix subject sie ‘she’.

3.1.2 Results

The six chosen verbs differed in their absolute frequencies of occurrence in combination with infinitival complements. While the raising verb scheinen and the control verb versuchen occurred most frequently with an infinitival construction, the other four verbs were attested considerably less often.Footnote 8 However, as expected, opposite distributions of word-order patterns were found between raising and control verbs, such that the two raising verbs scheinen and pflegen occurred with an intraposed infinitive in 100% of the cases, while for our control verbs, extraposition was the most frequent variant (see Table 2). A Fisher’s Exact Test on the absolute counts confirmed that verb type and distribution of attested word-order patterns were significantly associated (p < .001). No significant differences were found between the two raising verbs scheinen and pflegen (p = 1, using a Fisher’s Exact Test).

While neither scheinen nor pflegen were attested with an incoherent biclausal structure, three examples of pronoun fronting, exemplified in (10) and indicating a monoclausal coherent structure, were found with the verb pflegen.

(10) | wie | [es] | die | gastronomische | Literatur | bis | zur |

as | it.ACC | the.NOM | gastronomical | literature | until | to.theGEN | |

Übersättigung | ihrer | Leser | [zu | tun] | pflegt. | ||

oversaturation | itsGEN | readers | to | do | is.in.the.habit.of | ||

‘as the gastronomical literature usually does, until its readers are over-saturated’ | |||||||

(DeReKo: Z16/MAR.00507 Zeit, 17.03.2016, 51) | |||||||

Across all four control verbs extraposition was clearly the most frequent word-order pattern, ranging between 74.4 and 100% of occurrences. However, while for the three verbs ankündigen, bedauern and beschließen intraposition and third construction are rarely or not at all attested (see Table 2), most variability is observed with the verb versuchen, such that all three word-order patterns are attested: extraposition is dominant with 74.4%, intraposition follows with 23.3% and the third construction is attested with a rate of 2.3%. Pairwise comparisons between the control verbs revealed that versuchen differs significantly from the other verbs (vs. bedauern: p < .01, vs. ankündigen: p < .001, vs. beschließen: p < .001, using a Fisher’s Exact Test).

Of the intraposed infinitives with the verb versuchen, eight instantiations show evidence for a coherent construal. Example (9e) above is the only attested case of a pied-piped intraposed infinitive, and thus the only instance of unambiguously incoherent intraposition. The little variability within individual verbs also suggests that genre did not play a major role in determining word-order preferences, with one exception: The verb versuchen not only showed a more variable word-order behaviour than the other control verbs but also differences between the sub-corpora.

The third construction, exemplified in (9c) above, is almost exclusively found in the Twitter corpus (N = 59/65), compared to only six instances in the other sources (see Table 3). This result is not surprising, however, since the third construction is sometimes considered as a marked option in the written language (Wöllstein-Leisten 2001). Bosch et al. (2022) found that this pattern is indeed more frequent in spoken than in written corpora, and that Twitter data patterns with spoken data in this respect. In addition, Table 3 shows that the relative frequency of intraposed infinitives also differs among sub-corpora, with Twitter showing the smallest proportion of intraposed infinitives (12%) compared to the other written sources (30% in newspapers and 40% in fictional and scientific texts). Whilst the near-absence of the third construction from written corpora might at least partly reflect prescriptive norms, such norms cannot explain why intraposition is very rare as well, and especially rare in our Twitter corpus, thus suggesting that additional factors play a role in determining word-order preferences.

3.1.3 Discussion

The frequency distributions of the different word-order variants confirm Bayer et al.’s (2005) and Bosch et al.'s (2022) observation that intraposed infinitival complements only occur infrequently with subject control verbs, indicating that intraposition represents a marked word-order option. Differences among the investigated sub-corpora further suggest that this is even more so in spoken-like styles. Additionally, we conclude that word-order behaviour is in part lexically restricted, as witnessed by the observed difference between raising and control verbs: While raising verbs consistently occur with intraposed infinitives only, subject control verbs do not appear as a homogenous group, with versuchen exhibiting more variability than the other three control verbs.

Given that the intraposition was rarely attested for the control verbs under investigation, and the examples we found were almost always ambiguous between coherent and incoherent construals, we proceeded to test German speakers' coherence preferences experimentally. Considering that third construction patterns were hardly attested at all, collecting acceptability judgement should help us find out to what extent the third construction is considered a permissible word-order option by present-day German speakers.

3.2 Acceptability judgements

We carried out two complementary acceptability judgement experiments on the word-order behaviour of German infinitive-embedding verbs. These will allow us to test predictions derived from usage-based frameworks (e.g., Bybee 2006; Bybee and Beckner 2010) by examining the extent to which acceptability rating patterns align with corpus frequency distributions. We will also consider to what extent lexical properties of individual verbs or verb classes can account for participants' rating patterns. Experiment 1 compares extraposition, third construction, and coherent versus incoherent intraposition structures, and Experiment 2, intended as a partial replication of the former, examines both ambiguous and non-ambiguous intraposition patterns so as to allow for a better comparison of the judgement and corpus data.

Our corpus counts predict that we should find clear differences in the judgement patterns for raising compared to control verbs. Since the raising verbs scheinen and pflegen exclusively occurred with intraposed infinitival complements in our corpus data, they are expected to elicit high acceptability ratings for intraposed structures but poor ratings for all other word-order variants. We would also expect the raising verbs scheinen and pflegen to pattern alike from the point of view of formal linguistic approaches: Raising verbs should elicit high acceptability ratings for monoclausal intraposition structures and poor ratings for all other word-order variants.

In contrast, given that subject control verbs occurred most frequently with extraposed infinitival complements, they are expected to yield higher acceptability ratings for this condition than for all other word-order variants. The third construction pattern, which was attested only for the verb versuchen, is expected to elicit the poorest ratings overall. A similarly graded acceptability pattern would be expected from a processing perspective, with the added prediction that coherent or ambiguous intraposition should be favoured over incoherent intraposition.

With respect to verb-specific variation patterns, corpus frequency distributions predict a two-way distinction for control verbs: While the subject control verbs ankündigen, bedauern, and beschließen occurred hardly at all with intraposed infinitival complements or third constructions in our corpus data, the verb versuchen sits apart as it appeared with all possible word-order variants. According to our corpus data, all subject control verbs other than versuchen are expected to elicit poor ratings for both intraposition and third constructions.

According to Haider's (1993, 2010) binary classification system of control verbs in German, the obligatorily biclausal verbs ankündigen and bedauern should pattern together in eliciting better ratings for extraposed and incoherent intraposed relative to coherent intraposition. The optionally monoclausal verbs versuchen and beschließen, in contrast, should exhibit the highest degree of variability across both monoclausal and biclausal construals, with all word-order patterns being deemed reasonably acceptable. Wurmbrand's (2001) three-way distinction of German subject control verbs, on the other hand, predicts that the lexical restructuring verb versuchen should pattern differently from the reduced non-restructuring verb beschließen, with versuchen eliciting better ratings than beschließen for both monoclausal coherent infinitives and for the third construction.

3.2.1 Experiment 1

3.2.1.1 Participants

Experiment 1 included 39 participants (3 male, 36 female) aged between 18 and 44 years (mean: 25.9 years). All participants were native speakers of German living in Germany at the time of testing and did not report any language-related or other behavioural or neurological disorders.Footnote 9 The majority of them were students at different universities across the country who were recruited online, either via the SONA participant pool provided by the University of Potsdam or via e-mail contact. Participants were offered a small fee of 4€ as a reimbursement.

3.2.1.2 Materials

The experimental materials were constructed using the six chosen matrix verbs, which were combined with infinitival complements exhibiting different word-order patterns so that each verb appeared in four experimental conditions as shown in (11a–d).Footnote 10 To make sure that infinitival complements occurred in a verb-final (SOV) structure, the critical verbs and their infinitival complements were presented in subordinate clauses. Examples (11) and (12) illustrate item sets for Experiment 1 with the infinitive-embedding verbs versuchen and scheinen.

(11) | a. | extraposition | ||||||||

Julia | sagt, | dass | Fred | versucht | [ihn | zu | streicheln]. | |||

Julia | says | that | Fred | tries | him | to | pet | |||

b. | third construction | |||||||||

Julia | sagt, | dass | Fred | [ihn] | versucht | [zu | streicheln]. | |||

Julia | says | that | Fred | him | tries | to | pet | |||

c. | intraposition coherent | |||||||||

Julia | sagt, | dass | ihn | Fred | [zu | streicheln] | versucht. | |||

Julia | says | that | him | Fred | to | pet | tries | |||

d. | intraposition incoherent | |||||||||

Julia | sagt, | dass | Fred | [ihn | zu | streicheln] | oft | versucht. | ||

Julia | says | that | Fred | him | to | pet | often | tries | ||

‘Julia says that Fred tries to pet him (often).’ | ||||||||||

(12) | a. | extraposition | ||||||||

Julia | sagt, | dass | Fred | scheint | [ihn | zu | streicheln]. | |||

Julia | says | that | Fred | seems | him | to | pet | |||

b. | third construction | |||||||||

Julia | sagt, | dass | Fred | [ihn] | scheint | [zu | streicheln]. | |||

Julia | says | that | Fred | him | seems | to | pet | |||

c. | intraposition coherent | |||||||||

Julia | sagt, | dass | ihn | Fred | [zu | streicheln] | scheint. | |||

Julia | says | that | him | Fred | to | pet | seems | |||

d. | intraposition incoherent | |||||||||

Julia | sagt, | dass | Fred | [ihn | zu | streicheln] | oft | scheint. | ||

Julia | says | that | Fred | him | to | pet | often | seems | ||

‘Julia says that Fred seems to pet him (often).’ | ||||||||||

For all experimental sentences, a picture illustrating the entity referred to by the personal pronoun ihn in the subordinate clause was presented above the actual test sentence so as to provide an appropriate antecedent for the pronoun (see (13)).

In the extraposition condition (11a and 12a), the infinitival complement follows the matrix verb and is located at the right periphery of the sentence. The third construction (11b and 12b) represents a discontinuous construction, in which the accusative object of the infinitive ihn appears left-adjacent to the matrix verb while the infinitive zu streicheln appears in an extraposed position to its right. Conditions (11c, 12c) and (11d, 12d) both contain intraposed infinitives. Condition (11c, 12c) represents an unambiguously coherent structure as the object pronoun (ihn) has been scrambled out of the infinitival complement in front of the subject of the subordinate clause (here, ‘Fred’). In contrast, condition (11d, 12d) represents an unambiguously incoherent construal, with the infinitival complement projecting its own CP, which is signaled by the lack of adjacency between the infinitive and the subcategorizing verb: The infinitival complement and the matrix verb are separated by an intervening adverb (oft 'often'), which indicates the presence of a clause boundary between infinitive and matrix verb.

Twenty-four critical item sets were created by placing each of the six critical verbs in four different semantic sentence contexts and combining them with the four above-mentioned word-order patterns. Each sentence began with an introductory sentence fragment such as Julia sagt, dass… (‘Julia says that…’) followed by the remainder of the subordinate clause. The subordinate clauses all contained one of the critical matrix verbs combined with an infinitival complement. The infinitival verbs all appeared with a pronominal object in the dative or accusative case. This allowed us to use pronoun fronting as a coherence signal in (11c) and (12c) whilst ensuring that all four experimental conditions were close minimal pairs. Full lists of our experimental materials are available at the Center for Open Science Framework website (https://osf.io/a7rqd/).

In addition, Experiment 1 included 40 filler sentences which did not contain any infinitival complements and differed from our experimental items both in their lexical material and syntactic structure. We included both fully acceptable fillers such as Klaus glaubt, dass die Erklärungen des Lehrers nicht richtig sind. (‘Klaus believes that the teacher's explanations are incorrect.’) and fully ungrammatical fillers such as *Lena prüft, was verursacht beim Unfall für Schäden sie hat. (lit. ‘Lena checks what caused in the accident for damage she has.’). This served to mask the ultimate purpose of the experiment and allowed us to verify whether participants read the stimulus items attentively, and to encourage them to make use of the full range of our rating scale.

All experimental sentences were pre-tested in a plausibility rating task in order to make sure that all of them were easily readable and interpretable. In this pretest, 30 German native participants were recruited from among the student communities of the University of Potsdam and provided with an online questionnaire via Google Forms which asked them to rate the plausibility of sentences with intraposed (raising verbs) and extraposed (control verbs) infinitival complements on a scale from 1 (= ‘highly plausible’) to 5 (= ‘not plausible at all’). To make sure that participants were not presented with highly plausible sentences only, we created a set of 24 implausible sentences (e.g., Vera glaubt, dass Sven die Nudeln Gedichte sagen hört.—‘Vera believes that Sven hears the noodles recite poems.’) and mixed them with the critical and filler items from Experiment 1. Mean plausibility ratings per item were calculated, and any critical items or fillers, which elicited a low mean plausibility rating (> 2), were adapted for Experiment 1 so as to make them more plausible. This was the case for two experimental items. Finally, four different presentation lists were created using a Latin square design. Each list contained 24 critical items and 40 filler sentences presented in pseudo-randomized order, with not more than three critical items appearing in a row. This design made sure that each list contained four experimental sentences per critical verb, each in a different context and word-order variant. Hence, in order to avoid repetition effects, each participant saw each matrix verb in all experimental conditions but in different sentence contexts which were not repeated within a single list.

3.2.1.3 Procedure

The questionnaire was implemented via Google Forms and administered via the world-wide web. Upon opening the link to the experiment, participants were first asked to answer some biographical questions and to provide their consent to participating in our study. After reading the instructions, participants received three practise items to familiarize themselves with the experimental task. Then the main experiment started with the presentation of the first trial.

Participants were instructed to read each stimulus sentence carefully and then rate its acceptability on a 5-point Likert scale. Sentences were presented individually in Arial 20pt in black colour against a white background, with the judgement scale appearing right underneath each test sentence. The scale ranged from 1 labelled as “vollkommen akzeptabel” (‘totally acceptable’) to 5 labelled as “völlig inakzeptabel” (‘totally unacceptable’).Footnote 11 Points 2, 3, and 4 were not labelled on every single scale, but were introduced as 2 meaning “eher akzeptabel” (‘rather acceptable’), as 3 meaning “nicht sehr akzeptabel” (‘not very acceptable’), and as 4 meaning “eher inakzeptabel” (‘rather unacceptable’). All experimental trials were presented as illustrated in (13).

Here the picture of the dog provides a referent for the personal pronoun ihn, which occurs before the subordinate clause subject Fred. This visual illustration should make our stimulus sentences are more easily interpretable and more plausible for participants.

Participants could take as much time as they needed for each stimulus sentence. Once they had provided their acceptability judgement for a given sentence, the next trial started automatically. On average, Experiment 1 took approximately 25 min to complete.

3.2.1.4 Data analysis

The data from two participants were excluded from statistical analysis since they uniformly rated all experimental and filler items either with best (= 1) or worst (= 5) scores. For the remaining rating data we employed cumulative link mixed models (CLMM) for ordinal regression (Christensen 2018) from the ordinal package in R (R Core Team 2017). The factorial structure of our experiment was reflected in the structure of our models, which were held constant across by-participant and by-item random effects. As categorical fixed effect variables, the models included the factors ‘Verb Type’, comparing raising versus control verbs, the factor ‘Condition’, comparing the four word-order patterns under investigation, and for the follow-up analyses the factor ‘Critical Verb’ in order to examine effects of word-order variation across individual infinitive-embedding verbs. Also, interactions between these factors were included. Finally, the categorical factor ‘Experimental List’ and the continuous predictor ‘Trial Position’ (i.e., the rank of items in the task) were also included in the analyses, in order to control for task-related effects and to remove auto-correlation of residuals (Baayen and Milin 2010). Before including the continuous predictor ‘Trial Position’ in the models, it was centred around its mean. For determining the best-fit random slopes structure, we started with the maximal model including random intercepts and slopes for factors and their interactions. For models which failed to converge, we iteratively removed random slopes by participant or by item which explained the least variance (Barr et al. 2013) until the model did not improve any further according to its AIC value (Venables and Ripley 2002).Footnote 12 The best-fit model for each analysis is reported in the results section. For the overall model, we employed treatment contrasts to factors with extraposition as reference level for the factor ‘Condition’ and raising as reference level for ‘Verb Type’. For effects within factors we also employed treatment contrasts and the comparisons of interest were obtained by relevelling factors and refitting the model.

3.2.1.5 Results

Overall, raising verbs elicited the highest mean acceptability ratings for infinitival complements in the intraposed coherent condition (2.15), while all other complement types were rated considerably worse (extraposition: 3.41, intraposition incoherent: 4.05, third construction: 3.53). In sharp contrast to this, control verbs yielded the best ratings for extraposition compared to all other word-order variants (mean rating: 1.36). However, intraposed coherent complements, as well as those in the third construction, still elicited fairly acceptable ratings in the intermediate scalar range (intraposition incoherent: 3.51, intraposition coherent: 2.84, third construction: 2.63).

A CLMM including the factors ‘Verb Type’ and ‘Condition’ revealed significant effects of both predictors as well as a significant interaction (Table 4).

Given the interaction, further statistical analyses were conducted on raising and subject control verbs separately by including the factors ‘Condition’ and ‘Critical Verb’. For raising verbs (Fig. 1), these analyses revealed significant effects of the factor ‘Condition’: scheinen and pflegen elicited significantly better ratings for the intraposition coherent condition relative to the ratings of any other word-order pattern (intraposition coherent vs. extraposition: Estimate = 1.268; SE = 0.22; z = 5.640; intraposition coherent vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = 1.926; SE = 0.24; z = 8.112; intraposition coherent vs. third construction: Estimate = 1.436; SE = 0.23; z = 6.279). Extraposed infinitival constructions and third constructions did not statistically differ, but showed significantly better ratings than the intraposition incoherent condition (extraposition vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = 0.658; SE = 0.216; z = 3.043; third construction vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = 0.486; SE = 0.32; z = 2.240).

Additionally, we obtained significant interactions of the factors ‘Condition’ and ‘Critical Verb’, and thus reliable verb-specific variation patterns between the two raising verbs: While for the verb scheinen, the intraposition coherent condition yielded significantly better ratings than the other word-order variants (intraposition coherent vs. extraposition: Estimate = 2.086; SE = 0.30; z = 6.830; intraposition coherent vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = 2.343; SE = 0.32; z = 7.319; intraposition coherent vs. third construction: Estimate = 1.808; SE = 0.29; z = 6.239), pflegen did not only produce similar ratings for intraposition coherent and extraposed infinitival complements (intraposition coherent vs. extraposition: Estimate = 0.355; SE = 0.25; z = 1.413), but also elicited significantly better ratings for third constructions relative to scheinen (Estimate = 0.764; SE = 0.19; z = 4.087).

Participants' acceptability ratings also showed different patterns across our subject control verbs (Fig. 2). CLMMs including the factors ‘Condition’ and ‘Critical Verb’ firstly revealed significant effects of ‘Condition’. Extraposed infinitives were rated significantly better than all other word-order variants (extraposition vs. intraposition coherent: Estimate = 1.811; SE = 0.29; z = 6.245; extraposition vs. third construction: Estimate = 1.36; SE = 0.29; z = 4.728; p= .032; extraposition versus intraposition incoherent: Estimate = 1.96; SE = 0.29; z= 6.745), whereas intraposition coherent and third constructions did not elicit any statistically different rating patterns (Estimate = −0.45; SE = 0.26; z = 1.71), but were both judged as more acceptable than intraposition incoherent complements (intraposition coherent vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = 0.571; SE = 0.143; z = 3.985; third construction vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = 0.602; SE = 0.14; z = 4.218).

In addition, significant effects of the factor ‘Critical Verb’ and significant interactions between the factors ‘Condition’ and ‘Critical Verb’ were obtained, suggesting modulations of word-order behaviour across different individual control verbs.

Whilst extraposition was rated best across the board, planned comparisons between individual verbs also revealed significant differences: The verb versuchen elicited significantly better ratings for third constructions than all other verbs (beschließen: Estimate = 5.508; SE = 0.77; z = 7.158; bedauern: Estimate = 5.858; SE = 0.869; z = 6.742; ankündigen: Estimate = 5.294; SE = 0.81; z = 6.535). Additionally, the significant interactions between the factors ‘Condition’ and ‘Critical Verb’ for the four subject control verbs also show reliable verb-specific variation patterns with respect to their preferences for monoclausdal versus biclausal construals. In particular, versuchen yielded significantly better ratings for the intraposition coherent condition (relative to intraposition incoherent) than beschließen (Estimate = 1.001; SE = 0.48; z = 2.052), while beschließen, in turn, elicited significantly better ratings for coherent intraposition compared to both bedauern (Estimate = 0.923; SE = 0.46; z = 1.997) and ankündigen (Estimate = 0.761; SE = 0.366; z = 2.080). The latter two verbs did not significantly differ, however.

3.2.1.6 Summary

The raising verb scheinen elicited the highest acceptability ratings for intraposed coherent infinitives, while all other linearization patterns were rated considerably worse. The verb pflegen, however, elicited equally acceptable ratings for intraposed coherent and extraposed infinitival complements. These verb-specific variation patterns for scheinen and pflegen were neither predicted by corpus frequency distributions nor by formal linguistic assumptions about their coherence properties.

Control verbs yielded best ratings for extraposed infinitival complements compared to all other word-order variants. The verb versuchen showed substantial variability across alternative variants, however, eliciting significantly better ratings for third constructions than all other control verbs. This finding corresponds to our corpus frequencies, according to which versuchen was the only one of our four control verbs that occurred with third construction patterns. Recall, however, that versuchen only appeared in combination with third constructions in 2.3% of all cases in our corpus data, which was considerably less compared to its occurrence with intraposed structures (23.3%). Our finding that for versuchen the third construction was rated rather favourably (eliciting a mean rating of 1.72), and better numerically than either intraposition condition, was thus unexpected. These judgement patterns show that frequency of occurrence cannot fully predict the relative acceptability of German infinitival complements. In addition, the graded pattern of verb-specific acceptability for monoclausal relative to biclausal construals indicates substantial variability in coherence preferences across our four subject control verbs.

3.2.2 Experiment 2

3.2.2.1 Participants

Experiment 2 included 56 native speakers of German (34 female, 22 male) aged between 20 and 42 years (mean: 32.6 years). None of these participants had any background in Linguistics, reported any language-related or other behavioural or neurological disorders or were informed about the ultimate purpose of the study before testing. All of them were recruited from among the student and working communities in and around Potsdam and/or Berlin and reported not to be speakers of any particular German dialects.

3.2.2.2 Materials

Our experimental materials were similar to those used in Experiment 1 and were constructed around the same six infinitive-embedding verbs. In order to be able to directly compare our experimental data with the corpus frequency counts for intraposition, which were largely based on examples whose coherence status could not be determined, Experiment 2 included an ambiguous intraposition condition, replacing the third construction condition that was tested in Experiment 1. The four experimental conditions thus included extraposed infinitival complements and three intraposition conditions (ambiguous, coherent, and incoherent), as illustrated by example (14) for the verb versuchen.

(14) | a. | extraposition | ||||||||||

Finn | sagt, | dass | der | Junge | versucht | [sich | die | Hände | ||||

Finn | says | that | the | boy | tries | himself | the | hands | ||||

zu | waschen]. | |||||||||||

to | wash | |||||||||||

b. | intraposition ambiguous | |||||||||||

Finn | sagt, | dass | der | Junge | [sich | die | Hände | zu | ||||

Finn | says | that | the | boy | himself | the | hands | to | ||||

waschen] | versucht. | |||||||||||

wash | tries | |||||||||||

c. | intraposition coherent | |||||||||||

Finn | sagt, | dass | [sich] | der | Junge | [die | Hände | zu | ||||

Finn | says | that | himself | the | boy | the | hands | to | ||||

waschen] | versucht. | |||||||||||

wash | tries | |||||||||||

d. | intraposition incoherent | |||||||||||

Finn | sagt, | dass | der | Junge | [sich | die | Hände | zu | ||||

Finn | says | that | the | boy | himself | the | hands | to | ||||

waschen] | vergeblich | versucht | ||||||||||

wash | in.vain | tries | ||||||||||

‘Finn says that the boy tries to wash his hands (in vain).’ | ||||||||||||

The reflexive pronoun sich was used throughout (instead of a non-reflexive personal pronoun in Experiment 1) so as to allow us to use pronoun fronting as a coherence signal in condition (14c) whilst eliminating the need for adding a context picture. Experimental condition (14b) is structurally ambiguous between a coherent and an incoherent construal. In contrast, condition (14c) represents an unambiguously monoclausal structure as the reflexive pronoun sich has scrambled out of the infinitival complement to the front of the subordinate clause subject (here, der Junge ‘the boy’), whereas condition (14d) represents a biclausal construal indicated by the fact that the infinitival complement and the matrix verb are separated by the intervening adverb vergeblich ‘in vain’.

We created 24 critical item sets by placing each of the six critical verbs in four different sentence contexts. Each sentence began with an introductory clause such as Finn sagt, dass… (‘Finn says that…') followed by the rest of the subordinate clause which included the infinitive.

In addition, 16 filler sentences were added to the item set in order to mask the true purpose of the experiment and to encourage the full use of the judgement scale. Our filler sentences differed from the experimental sentences in their lexical material and syntactic structure, such that they mostly consisted of simpler sentences with conjunctions. We included both fully acceptable filler sentences and ungrammatical fillers such as *Den Pullover zu flicken Gisela nie (lit. ‘The sweater to patch Gisela never.’).

Critical items and fillers were distributed across four presentation lists in a Latin square design, such that each list contained 24 critical items plus 16 filler sentences, presented in pseudo-randomized order with no more than three critical items presented in a row.

3.2.2.3 Procedure

The questionnaire was again administered via the internet using Google Forms and generally followed the same procedure as Experiment 1. As Experiment 2 only included reflexives but no personal pronouns in the critical test items, no context pictures were presented along with the stimuli, however. Experiment 2 took approximately 15 minutes to complete.

3.2.2.4 Data Analysis

An error in the stimulus material in one of the four lists led us to exclude one of the experimental sentences containing the verb bedauern in condition (14c). This affected 14 data points, corresponding to an exclusion rate of 1.89%. The statistical data analysis followed the same procedure as in Experiment 1.

3.2.2.5 Results

Overall, raising verbs elicited the most favourable mean acceptability ratings in the intraposed ambiguous condition (1.96). This highly acceptable rating was closely followed by intraposed coherent infinitivals (2.05), while all other complement types were rated considerably worse (extraposition: 3.19, intraposition incoherent: 4.36). In contrast, subject control verbs yielded best ratings for extraposed infinitival complements (1.63) compared to all other word-order variants. However, ambiguous and coherent intraposed complements both elicited moderately acceptable ratings (intraposition incoherent: 3.75, intraposition coherent: 2.9, intraposition ambiguous: 2.8).

A CLMM including the factors ‘Verb Type’ and ‘Condition’ revealed a significant effect of ‘Condition’ as well as significant interactions of conditions across verb types (Table 5).

To follow up on these interactions, statistical analyses were conducted on raising and control verbs separately. For raising verbs (Fig. 3), significant effects of the factor ‘Condition’ were obtained: both verbs elicited significantly better ratings for ambiguous and coherent intraposition relative to the intraposition incoherent condition (intraposition ambiguous vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = − 2.212; SE = 0.291; z = − 8.048; intraposition coherent vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = − 2.212; SE = 0.284; z = 7.764). The ambiguous and coherent intraposition conditions did not significantly differ (Estimate = 0.130; SE = 0.26; z = 0.489). Interestingly, extraposed complements elicited significantly better ratings for raising verbs than incoherent infinitival complements (extraposition vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = − 1.09; SE = 0.28; z = − 3.886). Additionally, significant interactions of the factors ‘Condition’ and ‘Critical Verb’, and thus reliable verb-specific variation patterns between the two raising verbs were obtained: While for the verb scheinen extraposition was rated significantly worse compared to the intraposed ambiguous and coherent conditions (extraposition vs. intraposition ambiguous: Estimate = 1.921; SE = 0.238; z = 8.068; extraposition vs. intraposition coherent: Estimate = 1.939; SE = 0.25; z = 7.695), for the verb pflegen extraposed infinitival complements were rated as good as the intraposition coherent condition (Estimate = 0.336; SE = 0.234; z = 1.433).

Our participants showed different rating patterns for subject control verbs (Fig. 4). CLMM including the factors ‘Condition’ and ‘Critical Verb’ firstly revealed significant effects of ‘Condition’. Extraposed infinitives were rated significantly better than all other word-order variants (extraposition vs. intraposition ambiguous: Estimate = 1.893; SE = 0.31; z = 6.096; extraposition vs. intraposition coherent: Estimate = 2.315; SE = 0.311; z = 7.439; extraposition vs. intraposition incoherent: Estimate = 2.761; SE = 0.31; z = 8.784), while the ambiguous and coherent intraposition conditions did not elicit significantly different ratings (Estimate = 0.422; SE = 0.288; z = 0.231).

In addition, we found significant effects of the factor ‘Critical Verb’ as well as significant interactions between the factors ‘Condition’ and ‘Critical Verb’: While the verb versuchen elicited significantly better ratings for intraposed coherent infinitives than beschließen (Estimate = − 1.306; SE = 0.281; z = 4.644), beschließen still showed significantly better rating patterns for this monoclausal construal than ankündigen (Estimate = 0.822; SE = 0.26; z = 3.161) and bedauern (Estimate = 1.200; SE = 0.329; z = 3.647). The latter two verbs did not statistically differ, however.

3.2.2.6 Summary

Similarly to Experiment 1, raising verbs elicited the highest acceptability ratings for intraposed coherent and intraposed ambiguous complement types. However, in contrast to scheinen, the verb pflegen elicited comparable acceptability ratings for extraposed and intraposed coherent infinitives in both experiments. This rather striking difference between the two raising verbs' rating patterns was unexpected from corpus frequency distributions and indicates that only scheinen clearly favours monoclausal construals, whereas pflegen allows much more variability regarding the type of infinitival complement it selects. Control verbs, in contrast, received better ratings for extraposed infinitival complements compared to all other word-order variants. Intraposed ambiguous infinitival complements yielded the same acceptability ratings as intraposed coherent infinitives. Intraposed coherent structures elicited a graded pattern of verb-specific acceptability, with versuchen yielding the best and ankündigen/bedauern the worst ratings of this condition.

3.3 Self-paced Reading Experiment

The results from Experiments 1 and 2 showed that coherent or ambiguous intraposition was generally rated more favourably than incoherent intraposition even for control verbs, which are thought to select CP complements. A previous reading-time experiment on intraposed infinitival complements showed that intraposition serves as a coherence trigger (Bayer et al. 2005), such that incoherent construals elicit more processing cost in speakers of German, even for control verbs which resist clause union. To further test these previous claims to the effect that coherent construals are preferred for processing reasons, we carried out a self-paced reading cum paraphrase judgement task, which—unlike experimental methods that provide offline or end-of-sentence measures only—allows us to chart incremental word-by-word processing as it occurs and to pinpoint the source of potential increases in processing cost for intraposed infinitival complements.

3.3.1 Participants

We tested 55 German native speakers (seven male; mean age 24.64 years, range 18–38 years) from the Potsdam and Berlin area. They were recruited via the University’s participant database and social media contact. All participants reported to have grown up with only German being spoken at home and were not speakers of any non-standard German dialects. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision and did not report any language-related or other behavioural or neurological disorders. All participants gave their voluntary written consent and received a small fee for their participation.

3.3.2 Materials

In order to investigate the processing of coherent versus incoherent intraposed construals, we focused our investigations on subject control verbs exclusively. In addition to the four control verbs used previously, we added the subject control verbs planen (‘to plan’) and vorschlagen (‘to propose’) to our set of critical verbs for more variety. We created 24 minimal sentence pairs, four for each matrix verb, as illustrated in (15) below.

(15) | a. | Ambiguous | |||||||||||

Malte | hat | das | Buch | zweimal | zu | lesen | versucht, | aber | |||||

Malte | has | the | book | twice | to | read | tried, | but | |||||

ist | dabei | eingeschlafen. | |||||||||||

is | thereby | fallen.asleep | |||||||||||

‘Malte tried to read the book twice but fell asleep doing so.' | |||||||||||||

b. | Incoherent | ||||||||||||

Malte | hat | das | Buch | zu | lesen | zweimal | versucht, | aber | |||||

Malte | has | the | book | to | read | twice | tried, | but | |||||

ist | dabei | eingeschlafen. | |||||||||||

is | thereby | fallen.asleep | |||||||||||

‘Malte tried twice to read the book but fell asleep doing so.' | |||||||||||||

Both versions of our stimulus sentences contained an intraposed infinitival complement and one of the six chosen matrix verbs. Condition (15a) is globally ambiguous in that the infinitival complement can either be analysed as a clausal unit or as being integrated with the matrix clause via head merging with the subcategorising verb (i.e., versucht). The adverb zweimal can take scope either over the infinitive or the matrix verb. In the latter case, the accusative object das Buch must have undergone scrambling, thus indicating a coherent construal (i.e., the absence of a clause boundary). Condition (15b), in contrast, is disambiguated towards an incoherent construal as signalled by the adverbial being interposed between the infinitive and the matrix verb, which indicates the presence of a clause boundary.

In both conditions (15a) and (15b), from the point of view of left-to-right incremental processing, there is no evidence for the existence of a clause boundary at the point at which the DP das Buch is processed. At the infinitival marker zu, it becomes clear that an embedded infinitive must be integrated into the emerging sentence representation, with the (predicted) finite verb in press later on. In condition (15b), coming across the adverbial signals the need for the post-hoc insertion of a clause boundary, the insertion of a null subject and the establishment of a control relation. These processes may increase sentence processing cost in comparison to condition (15a). Ambiguous infinitival complements as in (15a) allow the reader to adopt a monoclausal analysis by forming a verbal complex of the infinitive zu lesen and the matrix verb versucht. A monoclausal coherent construal would render any structural reanalysis unnecessary and provide an elegant way for the parser to stick with its initial analysis. Although our set of matrix verbs also included a subgroup of verbs which are claimed to resist clause union (i.e., ankündigen and bedauern), we do not expect different RT patterns across matrix predicates based on our acceptability rating data, which did not elicit better ratings for intraposed incoherent construals relative to intraposed coherent complements for these verbs, as well as previous research which showed that readers did not revise an initial coherent analysis towards an incoherent construal when encountering a non-clause-union verb (Bayer et al. 2005).

However, Bader and Schmid’s (2009) VCCH predicts that the cost incurred by verb cluster formation should in fact lead to a processing disadvantage of coherent vs. incoherent construals at the point at which the two heads are merged. From an incremental processing perspective, the VCCH thus predicts increased processing cost for condition (15a) compared to condition (15b) when the matrix verb is encountered.

To obtain an indication of participants' interpretation of our stimulus sentences (15a,b) and to help ensure that they actively read for meaning, we combined the online reading task with an end-of-sentence paraphrase judgement task. We created two alternative paraphrases for each sentence. One of these corresponded to the adverbial taking infinitival scope and the other to the adverbial taking matrix scope, as shown in (16a,b).

(16) | a. | Infinitive scope paraphrase | |||||||

Malte | hat | versucht | das | Buch | zweimal | zu | lesen. | ||

Malte | has | tried | the | book | twice | to | read | ||

‘Malte has tried to read the book twice.’ | |||||||||

b. | Matrix scope paraphrase | ||||||||

Malte | hat | zweimal | versucht | das | Buch | zu | lesen. | ||

Malte | has | twice | tried | the | book | to | read | ||

‘Malte has twice tried to read the book.’ | |||||||||

For the ambiguous intraposition condition (15a), both paraphrases should be acceptable in principle. Whilst acceptance of the infinitive scope paraphrase (16a) would be compatible with either a coherent or an incoherent construal, acceptance of the matrix scope paraphrase (16b) would indicate a monoclausal coherent construal of the preceding sentence as this reading should be blocked if the infinitival complement is analysed as a CP. For the incoherent intraposition condition (15b), only the matrix scope paraphrase (16b) is appropriate as the adverbial directly precedes the matrix verb and thus should not be able to take infinitival scope.

The experimental sentences were distributed across four presentation lists in a Latin square design, pseudo-randomized and mixed with 36 filler sentences, resulting in 60 sentences per list, with not more than three critical items in a row. A subset of fillers (n = 12) resembled our experimental items in that they also included infinitival complements (with the reflexive pronoun sich), and the corresponding paraphrases rephrased the infinitival clause. Additional fillers represented different word-order variation phenomena. Half of the filler sentences were followed by appropriate, the other half by inappropriate paraphrases.

3.3.3 Procedure

The experiment was designed as a web-based study implemented via the experimental platform Ibex Farm (Drummond 2013), and participants received a link to access the experiment. We used a word-by-word, non-cumulative self-paced reading paradigm (Just et al. 1982), which allows readers to determine the presentation duration of each word using button presses. The presentation of each item began with a fixation cross. Pressing the space bar triggered the presentation of a stimulus sentence's first word. Each word was presented at the centre of the computer screen and was replaced by the next word when participants pressed the space bar. The final word in each sentence was presented with a full stop, and when participants pressed the space bar again, a paraphrase sentence appeared whose appropriateness participants had to judge by clicking on the ‘yes’ or ‘no’ button shown on the computer screen. The computer recorded participants' word-by-word reading times, their end-of-trial responses, and their response times.

The main experiment was preceded by a set of biographical questions and the presentation of three practice trials in order to familiarize participants with the experimental task. Both experimental and filler items were presented in black letters (30pt Lucida Grande font) against a light grey background, and there were four pre-programmed breaks during the experiment. The whole experiment could be completed in about 30 minutes. A progress bar shown above the stimulus sentences allowed participants to keep track of their progress during the experiment.

3.3.4 Data cleaning and analysis

One participant was excluded prior to any data analysis as it turned out that he/she was an early bilingual speaker.