Abstract

Emotion regulation is an essential component of prosocial behaviour and later life mental health outcomes. Group mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been shown to be effective at enhancing attention regulation and bodily awareness, skills necessary for efficient emotion regulation in children. We aimed to review the literature to determine whether MIB improved emotion regulation in children. Nine databases were systematically searched, yielding 502 papers. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, the inclusion criterium was applied to 68 full-text papers, leaving 15 eligible for inclusion. MBIs, including participants aged between 6 and 12 years old, and a quantitative post-intervention measure of emotion regulation were included. Data were extracted and synthesised following methodological quality assessment using PICO and Cochrane risk of bias tool. Data revealed mixed results regarding the efficacy of child-focused MBIs in improving emotion regulation. Results should be interpreted with caution due to disparate outcome measures of emotion regulation, mixed MBIs and poor methodological quality in many of the included studies. MBIs can be effective in improving ER in children. Further research is required to examine the effects in clinical samples with diverse baseline ER scores, determine the long-term effects of the MBIs, and explore moderators of treatment.

Highlights

-

MBIs can be effective at improving ER in children aged 6–12 years.

-

Consistent mindfulness sessions with followed home practice appear to be the best practice for improving ER.

-

Children from low socioeconomic areas, sourced from within the welfare system, or with mental or physical health diagnoses are less likely to complete full intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A child’s emotional well-being is vulnerable to a range of risk factors. Stressors such as family-system disturbances (i.e., divorce, death and/or incarceration of parental figure or family member), peer conflicts, socio-cultural challenges, and a range of physical and mental health problems can negatively influence the general functioning and well-being of children. The ability to effectively regulate one’s emotions during such stressful times is increasingly considered integral for well-being, academic success, and positive later life sequelae such as increased resilience and improved relationships (Metz et al., 2013). Consequently, contemporary psychology regards emotion regulation as integral to mental health, with emotion dysregulation underlying several mental health disorders (Berenbaum et al., 2003).

Emotion regulation has been defined as the conscious and unconscious strategies employed to maintain, increase, or decrease components of an emotional response, both positive and negative (Gross, 1998; Gruhn & Compas, 2020). Emotion regulation choice (ERC) involves the active selection of different regulatory strategies available to the individual to regulate their emotions (Sheppes et al., 2011). The choice of strategy depends on the availability of strategies for the individual, the broader context, the nature of the emotion, the individual doing the regulating, and the intensity of the emotional situation (Matthews et al., 2021). Research into treatments that can improve emotion regulation in children presenting with various clinical or developmental conditions is emerging. There is growing interest in using mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) to support the development of emotion regulation. Self-reported mindfulness has been linked to lower levels of emotional reactivity and negatively related to emotional labilities such as anger, sadness, shame, and guilt (Hill & Updegraff, 2012). Mindfulness may support quick affective reactions, allowing for the acceptance of the initial affect, quick mobilising of the regulatory resources, and minimising negative emotional reactions (Teper et al., 2013). Research among experienced meditators has demonstrated positive associations with attention regulation, body awareness and emotion regulation (Burzler et al., 2019; Tran et al., 2014).

Mindfulness practice has also been associated with neuroplastic changes, which together synergistically suggest enhanced self-regulation (Hölzel et al., 2011). In typically developing children, the capacity for emotion regulation is enhanced during grade school years, with improved emotional understanding and adaptive coping. School-aged children become aware of social display rules and differences between internal experiences and external emotional expression in themselves and others (Macklem, 2007). Despite this growing literature, a systematic review has yet to be published identifying the effect of mindfulness with children.

This systematic review aims to review studies using MBIs on children between 6–12 years of age to determine the effect on emotion regulation, as well as compare variables involved in MBIs to provide a clearer best-practice methodology. In previous literature, this age group has seen significant positive outcomes associated with ER regarding internalising and externalising behaviours, development of resilience, and reductions in mental illness symptoms (Conner et al., 2019; Gross, 1998; Jin et al., 2017; Mennin et al., 2015). As the protective effects of ER have been well outlined in this age group, investigating MBIs as an instigator for ER improvement is an important addition to the literature. This review focus specifically on Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) and other mindfulness interventions. A review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) interventions in children have previously been conducted; ACT will therefore not be included in this review (see Swain et al., 2015).

Mindfulness has been described as a state of consciousness that focuses on the moment-to-moment experience with openness, curiosity, and without judgement (Brown & Ryan, 2003). The three components of mindfulness have been highlighted as intention, attention, and attitude (Shapiro et al., 2015). Enacting these components (i.e., paying attention, on purpose, nonjudgmentally) improves self-management and emotional, cognitive, and behavioural flexibility. The mechanisms of mindfulness are focused attention, decentring (the ability to consider multiple aspects of a situation), and at its core, emotion regulation (Hölzel et al., 2011). Through continually bringing attention back to the present moment, noticing bodily sensations, current thoughts and emotions, mindfulness has been seen to increase attention, decrease rumination, and improve emotion regulation (Coffman et al., 2006; Turanzas et al., 2020). Improvements in these skills underpinning mindfulness have been linked with better management of negative experiences and resilience (Lee et al., 2008).

Though the definition of mindfulness is relatively universal, the implementation of its practices as an intervention is vast and diverse. With adults, the most often-used interventions are MBSR and MBCT (Segal et al., 2018). MBSR is an 8-week group intervention that cycles through specific exercises such as body scans and self-compassion exercises (Kabat-Zinn, 2011; Kabat-Zinn et al., 1985), whereas MBCT is an adaptation that uses cognitive techniques to disrupt patterns of thought by instructing participants to notice and identify thoughts and to see them as “just thoughts” (Coffman et al., 2006). In a recent review of 209 MBIs, moderate effect sizes were found for decreasing depression, anxiety, and stress compared to waitlist controls (Hedges’ g = 0.55; Khoury et al., 2020). However, the adaptations for children often use components from both and unique characteristics to make an intervention more feasible within the target population (e.g., schools, at-risk youth, or therapy). These interventions are often shorter and focus less on cultivating decentring than those targeted at adults. Instead, these interventions often focus on breath and body awareness through body scans, progressive relaxation, and sensory models to enhance internal and external environment experiences (Semple & Lee, 2014; van de Weijer-Bergsma et al., 2014). An emphasis is also placed on home practice, with less on reflection or enquiry. Focus on meta-cognition is removed for younger children where abstract thought is difficult to grasp, and activities are generally structured around being fun and game-like to maintain attention. These interventions tend to vary in efficacy but overall suggest improvements in well-being.

In summary, this systematic review aims to investigate whether or not child focused MBIs are effective at improving emotion regulation in children aged 6 to 12 years. This review will also consider the impact of the following variables on MBI outcome in children: outcome measure, duration and frequency of intervention, specific type of MBI evaluated, and intervention setting (home, school, or other).

Development of Search Strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was chosen to include peer-reviewed articles and assess available unpublished studies. In January 2022, systematic searches were performed in nine databases after a list of keywords was trialled in the EBSCO database for relevance. Databases included in the search were PsycInfo, PsycArticles, Cochrane Reviews, Medline, Pubmed, Scopus, Web of Science, Open Access Theses and Dissertations and Proquest. The list of search terms employed was:

(Emotion regulation OR emotion dysregulation OR regulation of emotion OR emotional regulation)

AND

(Children OR Kid* OR Child)

AND

(Mindfulness OR Mindfulness-Based Intervention OR MBI OR Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction OR MBSR OR MBCT)

Studies were searched from all available timeframes, and no language restrictions were applied. The databases which yielded the most relevant and accessible results were Cochrane, Web of Science and Pubmed. From database results, reference lists were examined and added if deemed relevant. After removing duplicates and screening abstracts of the remaining studies, full-text articles were examined by the first and second authors. If needed, authors of potential studies were contacted for further information. The first author independently extracted the data from the original reports; where inclusion uncertainty arose, these were solved by discussion.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Studies were selected for inclusion if: (i) Interventions were mindfulness-based; (ii) most participants were children aged 6–12 years old or grade 1 to 6; (iii) outcomes were quantitative; and (iv) had a clear outcome measure of emotion regulation.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Included studies were assessed with the Cochrane Risk of Bias (Higgins et al., 2020). This tool has been judged suitable for use in systematic reviews providing overall quality rating through the following components: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias. The quality assessment was carried out independently by the first author and checked by the second author, with disagreements resolved by discussion at each stage. A visual representation of this assessment can be seen in Fig. 2.

Data Extraction, Analysis, and Synthesis

Data on methodology and outcomes of included studies were extracted and coded by the first author and checked by the second author. Extracted data covered information on participants, sample size and study design, applied measures, and major findings reported in Table 1. More detail on the MBIs used in the included studies is presented in Table 2.

Results

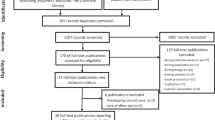

The initial search provided 502 possibly relevant records after the removal of duplicates. After excluding 434 papers with no relevance in abstract or title, 68 full-text papers were further screened against inclusion criteria. This final screening identified 15 studies to be included in this review. The most common reasons for exclusion at this stage were the lack of quantitative emotion regulation measure and participants outside the inclusion criteria age bracket of 6–12 years. The reasons for exclusion are presented in Fig. 1.

General Study Characteristics

Study characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Of the 15 studies identified, 12 were published in peer-reviewed journals, and one was in press. One Master’s and one PhD thesis were unpublished. The earliest study was published in 2013. Six studies were carried out in North America, seven in Europe, one in Canada, and one in the Philippines. In total, 1678 children were instructed in Mindfulness in the treatment conditions, and 697 served within a comparison group, ranging from grade kindergarten to grade 6, reflecting ages 6 to 12 years. Sample sizes varied between 19 and 454. Descriptions of methodology varied considerably across studies. Of the included studies, six were RCTs, seven were quasi-experimental designs, and two were single-group designs.

Six of the included studies involved children older than the specified age range of 6–12. Unfortunately, the age groups could not be separated out for all included studies due to unavailable data. A one-way ANOVA was run to examine if studies with participants outside the age range significantly predicted increases in mindfulness more than those with the specified age range; this was found to be non-significant [F(2,15) = 2.29, p = 0.143].

Intervention Variables

Outcome measures

Emotion regulation was measured in five studies using the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents or a variant. Three studies used the Emotion Regulation Checklist. For each of the remaining scales, these were employed once: Emotion Expression Scale for Children, Emotion Skills and Competency Questionnaire, Regulation of Emotions Questionnaire, Resiliency Scale for Children and Adolescents, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, and Differential Emotions Scale.

Time and frequency

The periods (frequency and length) of training varied from 5 weeks to 15 weeks (M = 9 weeks), with 30–120 min per session (M = 54.8). The efficacy of existing mindfulness programs in adult populations, such as MBSR and MBCT, is used as a theoretical justification for the chosen interventions in several of included studies. Other interventions refer to positive psychology or combine MBI with a special group of school-based intervention programs.

Type of MBIs employed

A total of six studies (two for each) employed MBCT, MBSR, MiSP or Pawsb as the MBI. For all other included studies, they were alone in employing their own specific MBI: Living Mindfully, Growing Minds, APAC, Mindup, Learning to Breathe or a unique modified mindfulness intervention.

Setting of intervention

Nine of the fifteen studies were conducted in a school environment. One was conducted at home, and all the others were in some form of university, psychology, or hospital clinic.

Risk of Bias

The overall risk of bias for six of the fifteen studies was moderate. Five studies were found to be high risk, and four exhibited low risk, refer to Fig. 2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to summarise available data on the effect of mindfulness-based training on emotion regulation in children. Fifteen unique studies were identified and published between 2013 and January 2022, highlighting the recent interest in mindfulness and emotion regulation. Despite the limited literature, encouraging results were found. Although some studies employed quasi-experimental or single-group designs, most were randomised control trials. Employed MBIs varied depending on population; most employed unique child-focused interventions specific to school environments, such as Paws b., or a child-friendly adaptation of MBSR or MBCT. Nine of the fifteen studies were conducted in school environments where most participants were from middle socio-economic status (SES) areas with small populations within the broader sample from low SES areas. Six of the fifteen studies were conducted outside of school environments and focused on at-risk children sourced through the welfare system, children with a mental or physical health diagnosis, or from low socioeconomic status (SES) areas. Emotion regulation was measured using ERC, ERQ-CA, DERS, emotion regulation subscales of other larger measures, and various language-dependent variations of the emotion regulation scales. Due to the inconsistency of emotion regulation scales employed and the various internal consistency (ERC = 0.83–0.96; ERQ-CA = 0.73–0.81, DERS = 0.93; EESC 0.81–83; REQ = 0.66–0.76), results and effects sizes were interpreted with caution. Several studies (Coholic & Eys, 2016; Sibinga et al., 2013; Sibinga et al., 2017) reported on emotion regulation using a measure comprising two questions in a different non-emotion regulation-specific scale. No information regarding construct validity or test-retest reliability is available for these measures, impeding interpretation. That withstanding overall, MBIs appear to have the propensity to improve emotion regulation in children, with most studies reporting statistically significant results. Mindfulness programs are feasible across different populations of children and are enjoyed and valued by most children from these studies. Our review harmonies with previous studies (Joss et al., 2019; Quaglia et al., 2019) highlighting the role of MBIs in improving self-and emotion regulation in children (Flook et al., 2015). It is noteworthy that sex differences in response to mindfulness may play a role in the development of emotion regulation (Bluth et al., 2017). However, from the studies investigated, no significant sex difference was reported. Despite limited research, there appear to be patterns within this population that may improve best practice for developing emotion regulation MBI interventions.

Of the included interventions, those which required homework from the participants with low time demands (3–10 min) were more likely to result in significant improvements in emotion regulation, except for Growing Minds in US students and the mMBCT conducted with Filipino students, which had high time demands (10 min or more). All studies with included homework reported relatively high adherence. Alampay et al. (2020) concluded that if the intervention added stress to the participant through high time demands, the intervention was less likely to be effective in improving emotion regulation. This is a possible reason Growing Minds and mMBCT saw less success than the other interventions, for which homework requirements were high-time intensive activities. All homework activities included the repeated practice of the learnt skills and integration of the practice into daily life outside of the intervention context may also explain the positive effects of homework on ER. Mindfulness in the home setting, which may also involve parents, has been seen to improve child ER significantly, which may also contribute to the effect (Zhang et al., 2019).

While most included studies provided training to the teachers or facilitators of the intervention, both MBSR and MBCT stress the importance of extensive personal experience, the embodiment of attitudinal foundations of mindfulness, as well as established and ongoing mindfulness practice, professional training, attendance in silent retreats and ongoing professional development (Kabat-Zinn, 2011; Segal et al., 2018). This may have contributed to the small effect size of the intervention, as not all studies demonstrated that their facilitators met these criteria.

One of the major difficulties in compiling and comparing the results of these studies was the variations of measures used. Yet, there is no one clear measure to determine ER in children, and many of the scales are only validated in a handful of settings and ages. Further, no study compared their results with clinical norms to determine whether the children involved were at baseline high in emotion regulation compared to a normative sample. The age range of participants also presented issues. Several studies used measures that had not been validated for their participants’ full range of ages. The studies conducted on children from low SES areas or from within welfare systems also reported higher drop-out compared to studies conducted within school systems. The intervention method should be critically evaluated to improve adherence across all cohorts of children, particularly those most at risk. In studies that conducted adherence and engagement questionnaires or qualitative follow-up studies, a very high percentage of those who completed the intervention said they enjoyed it. Researchers should investigate what is causing initial dropout with the aim of improving overall adherence.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

Several limitations within the literature need to be discussed. Not all included studies reported enough data to create effect sizes or to compare z-scores to see reliable change across time, regardless of measures or intervention. Unfortunately, meta-analysis is currently impossible with this specific topic and a concern for the topic area. More cohesion, and transparency on the part of researchers, are needed to allow for replication studies to provide clearer insight. The quality of evidence for the efficacy of the MBIs was limited by the biases present in many of the studies. Eleven of the fifteen included studies scored moderate or high risk of bias overall. Measuring the effects of the interventions is dependent upon the quality of assessment metrics, measures, and assessment of emotion regulation with novel or modified measures could severely limit the reliability and validity of the results. The methodological and statistical heterogeneity between studies also limits the results of this systematic review. While most studies included in this review reported participant characteristics such as race and ethnicity, very few included information on children with disabilities, receiving education support, or previous behavioural difficulties.

Given that most of these studies were conducted in group settings, it is possible that these interventions are not well suited to the specific needs of children with special needs who would benefit most from improvements in emotion regulation. Those that did target at-risk children, such as those in the welfare system or at-risk urban areas, did not use robust measures of ER, making it difficult to conclude whether mindfulness interventions are more or less effective for these children (Coholic & Eys, 2016; Sibinga et al., 2013; Sibinga et al., 2017). Several studies included participants outside the age range; children aged 13 and over or five and younger may have skewed the results. Seven of the fifteen studies included adolescents. As mixed findings have been reported on intervention success within the age group, this is a significant limitation (de Bruin et al., 2014; McKeering & Hwang, 2019; Thompson & Gauntlett-Gilbert, 2008). Unfortunately, the participants outside the age range could not be partitioned out due to a lack of available data. This is a key limitation of this review.

Conclusion

This systematic review has important implications for future research on MBIs for improving emotion regulation. For example, more RCTs are needed to examine the effectiveness of these treatments compared to no-treatment groups; age-ranges need to be provided. Our results suggest interventions with at-home exercises and facilitation by trained mindfulness experts may produce greater effects on emotion regulation. Most studies did not investigate individual improvements in emotion regulation and focused on the total group score, which limits understanding of what children may benefit most from mindfulness interventions. RCTs investigating which groups of children benefit from MBIs targeting emotion regulation are imperative to determining best practice and efficient program directions. More extended follow-up periods are needed to examine the long-term effects of MBIs on emotion regulation, as most of the studies included in this review followed their samples for only three months or immediately post-intervention. Ideally, these follow-up periods will also include waitlist conditions to examine whether the changes are due to the natural course and development of the intervention.

Though our systematic review suggest that MBIs can improve emotion regulation in children, the limitations of the literature, including the quality of evidence and the assessment of emotion regulation, require caution when interpreting the results. What can be garnered from the small number of studies included in this review is that interventions with homework activities are more effective than those without and that children from low SES areas, within the welfare system or with mental/physical health diagnoses are less likely to complete an entire course of the intervention. This highlights the need for engagement and adherence-focused approaches. Future research should aim to determine the long-term effects of the MBIs, and explore moderators of treatment, such as whether emotionally dysregulated children benefit equally. Carefully designing applied research mindfulness projects with robust measures of emotion regulation, considering time, effort, and stress reduction are all important. Emotion regulation is a promising area with huge benefits if nurtured in children. MBIs appears to be one tool that can improve ER. However, participants’ demands of time and effort must complement the philosophy of mindfulness, stress reduction and emotion regulation to succeed.

References

Alampay, L. P., Tan, L., Tuliao, A. P., Baranek, P., Ofreneo, M. A., Lopez, G. D., Fernandez, G. F., Rockamn, P., Villasanta, A., Angangco, T., Freedman, M. L., Cerswell, L., & Guintu, V. (2020). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness program for Filipino children. Mindfulness, 11(2), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01124-8.

Amundsen, R., Riby, L. M., Hamilton, C., Hope, M., & McGann, D. (2020). Mindfulness in primary school children as a route to enhanced life satisfaction, positive outlook and effective emotion regulation. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 71 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00428-y.

Andreotti, E., Antoine, P., Hanafi, M., Michaud, L., & Gottrand, F. (2017). Pilot mindfulness intervention for children born with esophageal atresia and their parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0657-0.

Berenbaum, H., Raghavan, C., Le, H.-N., Vernon, L. L., & Gomez, J. J. (2003). A taxonomy of emotional disturbances. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 206–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg011.

Bluth, K., Roberson, P. N. E., & Girdler, S. S. (2017). Adolescent sex differences in response to a mindfulness intervention: a call for research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(7), 1900–1914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0696-6.

Brown, K., & Ryan, R. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Burzler, M. A., Voracek, M., Hos, M., & Tran, U. S. (2019). Mechanisms of mindfulness in the general population. Mindfulness, 10(3), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0988-y.

Coffman, S. J., Dimidjian, S., & Baer, R. A. (2006). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of depressive relapse. Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches: Clinician’s Guide to Evidence Base and Applications, 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012088519-0/50003-4.

Coholic, D. A., & Eys, M. (2016). Benefits of an arts-based mindfulness group intervention for vulnerable children. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0431-3.

Conner, C. M., White, S. W., Beck, K. B., Golt, J., Smith, I. C., & Mazefsky, C. A. (2019). Improving emotion regulation ability in autism: the emotional awareness and skills enhancement (EASE) program. Autism, 23(5), 1273–1287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318810709.

de Bruin, E. I., Zijlstra, B. J., & Bögels, S. M. (2014). The meaning of mindfulness in children and adolescents: further validation of the child and adolescent mindfulness measure (CAMM) in two independent samples from the Netherlands. Mindfulness, 5(4), 422–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0196-8.

de Carvalho, J. S., Pinto, A. M., & Marôco, J. (2017). Results of a mindfulness-based social-emotional learning program on portuguese elementary students and teachers: a quasi-experimental study. Mindfulness, 8(2), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0603-z.

Deplus, S., Billieux, J., Scharff, C., & Philippot, P. (2016). A mindfulness-based group intervention for enhancing self-regulation of emotion in late childhood and adolescence: a pilot study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(5), 775–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9627-1.

Flook, L., Goldberg, S. B., Pinger, L., & Davidson, R. J. (2015). Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based kindness curriculum. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038256.

Fung, J., Guo, S. S., Jin, J., Bear, L., & Lau, A. (2016). A pilot randomized trial evaluating a school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth. Mindfulness, 7(4), 819–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0519-7.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271.

Gruhn, M. A., & Compas, B. E. (2020). Effects of maltreatment on coping and emotion regulation in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review. Child Abuse Neglect, 103, 104446 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104446.

Hafeman, D. M., Ostroff, A. N., Feldman, J., Hickey, M. B., Phillips, M. L., Creswell, D., Birmaher, B., & Goldstein, T. R. (2020). Mindfulness-based intervention to decrease mood lability in at-risk youth: preliminary evidence for changes in resting state functional connectivity. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.042.

Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M., Welch, V. (2020). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Hill, C. L., & Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion, 12(1), 81 https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026355.

Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671.

Jin, Z., Zhang, X., & Han, Z. R. (2017). Parental emotion socialization and child psychological adjustment among Chinese urban families: mediation through child emotion regulation and moderation through dyadic collaboration. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(2198). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02198.

Joss, D., Khan, A., Lazar, S. W., & Teicher, M. H. (2019). Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on self-compassion and psychological health among young adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 (2373). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02373.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2011). Some reflections on the origins of MBSR, skillful means, and the trouble with maps. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2011.564844.

Kabat-Zinn, J., Lipworth, L., & Burney, R. (1985). The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8(2), 163–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00845519.

Khoury, B., Gregoire, S., & Dionne, F. (2020). The interpersonal dimension of mindfulness. Annales Medico-Psychologiques, 178(3), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2018.10.018.

Lawler, J., Esposito, E. A., Doyle, C. M., & Gunnar, M. R. (2015). A randomized-controlled trial of mindfulness and executive function trainings to promote self-regulation in internationally adopted children. Developmental Psychopathology, 31(4). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418001190.

Lee, J., Semple, R. J., Rosa, D., & Miller, L. (2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: results of a pilot study. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 22(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889.8391.22.1.15.

Macklem, G. L. (2007). Practitioner’s guide to emotion regulation in school-aged children. Springer Science & Business Media.

Matthews, M., Webb, T. L., & Sheppes, G. (2021). Do people choose the same strategies to regulate other people’s emotions as they choose to regulate their own? Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo000100810.1037.

Mckeering, P., & Hwang, Y. S. (2019). A systematic review of mindfulness-based school interventions with early adolescents. Mindfulness, 10, 593–610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0998-9.

Mennin, D. S., Fresco, D. M., Ritter, M., & Heimberg, R. G. (2015). An open trial of emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder and cooccurring depression. Depression and Anxiety, 32(8), 614–623. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22377.

Metz, S. M., Frank, J. L., Reibel, D., Cantrell, T., Sanders, R., & Broderick, P. C. (2013). The effectiveness of the learning to BREATHE program on adolescent emotion regulation. Research in Human Development, 10(3), 252–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2013.818488.

Quaglia, J. T., Zeidan, F., Grossenbacher, P. G., Freeman, S. P., Braun, S. E., Martelli, A., Goodman, R. J., & Brown, K. W. (2019). Brief mindfulness training enhances cognitive control in socioemotional contexts: behavioral and neural evidence. PloS One, 14(7), e0219862 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219862.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, M., & Teasdale, J. (2018). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. Guilford Publications.

Semple, R. J., & Lee, J. (2014). Chapter 8 - Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-based treatment approaches (2nd ed., pp. 161–188). San Diego: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-416031-6.00008-6.

Shapiro, S. L., Lyons, K. E., Miller, R. C., Butler, B., Vieten, C., & Zelazo, P. D. (2015). Contemplation in the classroom: a new direction for improving childhood education. Educational Psychology Review, 27(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-014-9265-3.

Sheppes, G., Scheibe, S., Suri, G., & Gross, J. J. (2011). Emotion-regulation choice. Psychological science, 22(11), 1391–1396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611418350.

Sibinga, E., Webb, L., & Ellen, J. (2017). Mindfulness instruction improves anger regulation in US urban male youth. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-1783-3.

Sibinga, E. M., Perry-Parrish, C., Chung, S. E., Johnson, S. B., Smith, M., & Ellen, J. M. (2013). School-based mindfulness instruction for urban male youth: a small randomized controlled trial. Preventative Medicine, 57(6), 799–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.08.027.

Swain, J., Hancock, K., Dixon, A., & Bowman, J. (2015). Acceptance and commitment therapy for children: a systematic review of intervention studies. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 4(2), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.02.001.

Teper, R., Segal, Z. V., & Inzlicht, M. (2013). Inside the mindful mind: how mindfulness enhances emotion regulation through improvements in executive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 449–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/096372141349586.

Thompson, M., & Gauntlett-Gilbert, J. (2008). Mindfulness with children and adolescents: effective clinical application. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13(3), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104508090603.

Tran, U. S., Cebolla, A., Glück, T. M., Soler, J., Garcia-Campayo, J., & von Moy, T. (2014). The serenity of the meditating mind: a cross-cultural psychometric study on a two-factor higher order structure of mindfulness, its effects, and mechanisms related to mental health among experienced meditators. Plos One, 9(10), e110192 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110192.

Turanzas, J. A., Cordon, J. R., Choca, J. P., & Mestre, J. M. (2020). Evaluating the APAC (mindfulness for giftedness) program in a Spanish sample of gifted children: a pilot study. Mindfulness, 11(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0985-1.

van de Weijer-Bergsma, E., Langenberg, G., Brandsma, R., Oort, F. J., & Bögels, S. M. (2014). The effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness training as a program to prevent stress in elementary school children. Mindfulness, 5(3), 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0171-9.

Vickery, C. E., & Dorjee, D. (2016). Mindfulness training in primary schools decreases negative affect and increases meta-cognition in children. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02025.

Willenbrink, J. B. (2018). Effects of a mindfulness-based program on children’s social skills, problem behavior, and emotion regulation. (Publication No. 1950) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global

Wimmer, L., & Dorjee, D. (2020). Toward determinants and effects of long-term mindfulness training in pre-adolescence: a cross-sectional study using event-related potentials. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 19(1), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1891/jcep-d-19-00029.

Zhang, W., Wang, M., & Ying, L. (2019). Parental mindfulness and preschool children’s emotion regulation: the role of mindful parenting and secure parent-child attachment. Mindfulness, 10(12), 2481–2491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01120-y.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rowland, G., Hindman, E. & Hassmén, P. Do Group Mindfulness-Based Interventions Improve Emotion Regulation in Children? A Systematic Review. J Child Fam Stud 32, 1294–1303 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02544-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02544-w