Abstract

Caregivers of children with special health care needs (CSHCNs), especially those whose children have emotional, behavioral, or developmental problems (EBDPs), experience considerable strain and stress related to caring for their child’s special needs. The enormous burden of caregiving can decrease a parent’s ability to provide care, impacting the health of the child, the parents, and overall family functioning. To manage these challenges, these parents report the need for mental health care for themselves or their children, but many families with need go without care. Comprehensive knowledge about barriers to family mental health care for families of CSHCN is lacking. This study examines data from the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (2005/2006 and 2009/2010) to estimate time-specific, population-based prevalence of fourteen specific barriers to family mental health services and identifies risk factors for experiencing barriers to care for families of CSHCN. Among all CSHCN, cost barriers (33.5%) and lack of insurance (15.9%) were the most commonly reported obstacles to service access in 2005 and 2009, followed by inconvenient service times (12.3%), and locations (8.7%). Reports of these barriers increased significantly from 2005 to 2009. All types of barriers to family mental health services were reported significantly more frequently by CSHCN with EBDPs than by those without. CSHCN’s race, insurance, and parent education and income levels were factors associated with cost barriers to family mental health care. Understanding barriers to mental health care for families of CSHCN is critical to creating policy and practice solutions that increase access to mental health care for these families.

Highlights

-

Cost barriers, lack of insurance, and inconvenient service times and locations were the most commonly reported obstacles to service access in 2005 and 2009.

-

Rates of reported cost, service time, and service location or availability barriers increased from 2005 to 2009.

-

CSHCN’s race, insurance, and parent education and income levels were associated with cost barriers to family mental health care.

-

Parent education level was associated with increased rates of reported scheduling problems.

-

CSHCN’s residence in an urban area was associated with reduced frequency of reports of service location or availability barriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN) often require numerous medical appointments, medications, and physical and emotional accommodations and assistance—which requires significant time, energy, and financial expenditures from the supporting family (Caicedo, 2014). Caregivers experience considerable strain and stress related to caring for their child’s special needs, and the enormous physical and emotional burdens and time commitments of caregiving can decrease a parent’s ability to provide care, impacting the health of the child, the parents, and overall family functioning (Nygård & Clancy, 2018). Caregiving strain can be exacerbated by lack of financial resources, insufficient social support, and significant functional impairments in children (Green et al., 2020).

About 30% of CSHCN have an emotional, behavioral, or developmental problem (EBDP) (Ganz & Tendulkar, 2006), with or without a co-occurring chronic health condition (Bramlett et al., 2009, Inkelas et al., 2007). Caregivers of children with EBDPs, who often exhibit more complex and emotionally demanding needs, may be particularly at risk for negative family experiences related to caregiver strain (Brannan et al., 2018). For these parents, more stressors exist. The need to reduce work hours, the need for flexibility in work arrangements, and compromised work performance can result from the greater demands of caregiving for their child (Brannan et al., 2018; Ghandour et al., 2011). Compared with parents of children with other types of special needs, those whose children have emotional or behavioral concerns experience greater financial strain and employment impacts (Vohra et al., 2014), are more likely to end their relationship in separation or divorce (Wei & Yu, 2012), and are more likely to experience difficulties navigating and engaging with health service systems (Nageswaran et al., 2011; Vohra et al., 2014). Also, siblings of children who have EBDPs often exhibit adjustment difficulties (Kilmer et al., 2010), and many demonstrate academic and conduct problems, experience justice system involvement, and engage in substance use (Aguilar et al., 2001).

To manage these challenges, parents of CSHCNs with EBDPs report the need for family support services, including assistance with coordinating health care, respite care, peer support, or family or individual counseling (Graaf et al., 2021; Lutenbacher et al., 2005). Specifically, among families of CSHCN, national estimates in the United States suggest that 12% experience the need for mental health services for one or more family members (Graaf et al., 2021).

Mental health services, such as family or individual counseling, may be especially important as research indicates that caregivers’ perceptions of being an effective caregiver are related to reduced caregiving strain (Green et al., 2020). Family mental health services may be instrumental in increasing positive perceptions of caregiver efficacy and expectations –which may help to reduce caregiver strain and related family functioning. However, 21% of families with need for mental health care are unable to access these services for family members (Graaf et al., 2021). Rates of perceived need for family mental health care as well as reports of unmet mental health care need among these families are significantly higher for families of CSHCN with EBDPs (Graaf et al., 2021).

Barriers to Mental Health Care for Families of CSHCN

Gelberg et al. (2000) presents a model for understanding access to health care among vulnerable populations that can be applied to understanding barriers to mental health care for families of CSHCNs. To address the unique circumstances of vulnerable populations, including children and adolescents, those with mental illness, chronic illness and disabilities, Gelberg and colleagues build on the Behavioral Model (Andersen, 1995) for understanding health care access. The Behavioral Model is organized around understanding predisposing factors (e.g., age, sex, education level), enabling factors (e.g., usual source of health care, income, insurance coverage, residential location), and health care need (e.g., perceived health or need for health care) as predictors of health behavior, utilization, and outcomes. The model has been utilized widely to understand access to behavioral health services (Graaf et al., 2021; Graaf & Snowden, 2018; Jensen et al., 2021; Roberts et al., 2018).

The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg et al., 2000) adds predisposing and enabling factors to the original framework that are specific to more vulnerable or marginalized populations. Predisposing factors that can influence health behavior for this population include mobility, mental illness, or psychological resources and enabling factors can include transportation, information resources, and availability of care coordination. Because the lives of families who have a CSHCN are shaped in significant ways by the disability, chronic illness, or mental illness of their child, the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations may be useful in understanding the factors that may shape their access to mental health care for family members.

Though mental health services are often covered to some extent by private or commercial health insurance, lack of insurance, co-pays, service limits, health plan deductibles, and long waitlists are reported to play a role in unmet mental health care need for family members (Lutenbacher et al., 2005; Pilapil et al., 2017). Caregivers report difficulty in obtaining relevant and accurate information about available supports and services—where to find them, and how to access them (Lutenbacher et al., 2005; Pilapil et al., 2017). Parents of CSHCN also report concerns about separating from their child, and experience service location problems, long wait times for services, and stigma around seeking mental health care (Devine et al., 2016).

Risk of unmet mental health care needs for family members is greater for CSHCN with more complex health needs, adolescent CSHCN, those with moderate family income levels, and CSHCN with no health coverage (Ganz & Tendulkar, 2006; Inkelas et al., 2007). Among CSHCN with EBDPs, less stable health needs, lack of health coverage, and higher levels of parental education are associated with increased risk of unmet mental health care need for family members, but higher family income levels are associated with lower rates of unmet need (Inkelas et al., 2007). Although public insurance has been found to be associated with reductions in unmet mental health care need for CSHCN when compared to private insurance (Derigne et al., 2009; Graaf & Snowden, 2019), a CSHCN’s type of health coverage is not significantly associated with unmet family mental health needs (Graaf et al., 2021, Inkelas et al., 2007).

The Current Study

Though a handful of studies have examined parent reports of barriers to mental health care for themselves or other family members (Devine et al., 2016; Lutenbacher et al., 2005; Pilapil et al., 2017), studies are limited by small sample sizes and regional data collection. Though national estimates of perceived and unmet family mental health need have been reported for CSHCN (Inkelas et al., 2007), barriers to these mental health services have not been reported with nationally representative data. Further, national estimates of parent reported barriers to these services have not been examined over time. As such, comprehensive knowledge about the prevalence of different types of barriers to family mental health care and how they have changed in response to an ever-changing health care environment is lacking. The purpose of this study is two-fold: (1) to estimate time-specific, population-based prevalence of 14 specific barriers to family mental health services, as reported by parents of CSHCNs with and without EBDPs; and (2) to identify individual, family, and environmental characteristics associated with the three most prevalent barriers to mental health care for families of CSHCN.

Methods

Data and Sample

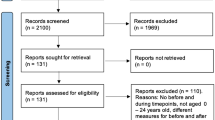

Data were drawn from two different administrations of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN), collected in 2005/2006 and in 2009/2010 (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2005, 2009). The 2005/2006 and 2009/2010 NS-CSHCN both report in-depth state and nationally representative parent-reported information on the health status and health care experiences of children and adolescents with special health care needs and their families in the United States (Blumberg et al., 2008; Bramlett et al., 2014). The survey was funded by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and was developed to support evaluation of federal block grants (Title V of the Social Security Act) to states for the development of coordinated systems of care for CSHCN. It was designed to provide estimates that are comparable across states regarding the prevalence of CSHCN, the types of services that these children need and use, and to identify areas for improvement in state systems of care. Data were collected as part of the State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey (SLAITS) program, sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). This initiative was a broad-based, ongoing survey system available at national, state, and local levels to track and monitor the health and well-being of children and adults.

The NS-CSHCN has been discontinued and has been integrated into the newly revised National Survey of Children’s Health (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative) (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative CAHMI (2019)). In the integration process, specific questions about access to mental health care for family members of CSHCN and reports of specific barriers to family mental health care were dropped from the survey when it was launched in 2016. As result, the data used in this study represent the most recent nationally representative data regarding this topic.

The datasets exclusively include data about children and youth that were identified as CSHCN through the Children with Special Health Care Needs Screening Tool (Bramlett et al., 2009). The CSHCN Screener uses a health consequences approach to determining special health care needs. It uses five stem questions on general health needs that could be the consequence of chronic health conditions (e.g., need for special therapies or need for prescription medication), and if a child currently experiences one of these consequences, followup questions determine whether this health care need is the result of a medical, behavioral, or other health condition and whether the condition has lasted or is expected to last for 12 months or longer. Those with affirmative answers to the stem and both followup questions are considered to have a special health care need.

Additional descriptions about SLAITS, the survey sampling methods, and data preparation are detailed in other sources (Blumberg et al., 2008; Bramlett et al., 2014). The resulting survey data were weighted to reflect the population of non-institutionalized children ages 0–17 years at the state and national levels. For this study, data from both the 2005/2006 and 2009/2010 surveys were pooled, ensuring matching of variables across years, and adjusting data stratification and weighting accordingly. Changes to the survey made between data collection waves that affected the current study were minimal (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2012). Because a small portion of the sample (<0.01%) responded “Don’t Know” or “Refused to Answer” to identifying the sex of the CSHCN, these observations were excluded from the original total sample of 80,242, for a final analytic sample of 79,249.

Measures

Using the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg et al., 2000), this study examines predisposing characteristics (age, sex, and race/ethnicity), enabling characteristics (income, insurance type, continuous health coverage, family language and structure, parent education, urban vs. rural residence, source of usual health care, and local mental health infrastructure), and need characteristics (EBDP, functional impairment) as factors associated with reported barriers to mental health services for families of CSHCN. In a systematic review of factors associated with mental health service utilization, all of these variables have been found to be significantly related to mental health care access (Roberts et al., 2018).

Survey Variables

The construction of sampling and outcome variables, Need for Family Mental Health Services, Unmet Family Mental Health Need, and specific Barriers to Family Mental Health Care, is described in detail in Table 1. To assess Need for Family Mental Health Services, the survey asked, “During the past 12 months was there any time when you or other family members needed mental health care or counseling related to your child’s medical, behavioral, or other health conditions?” If the answer to this question was “yes”, the survey then asked the following “Did you or your family receive all the mental health care or counseling that was needed?” to assess Unmet Family Mental Health Need. If the answer to this second question was “no” the survey then asked the following to capture specific Barriers to Family Mental Health Care: “Why did you or your family not get all the mental health care or counseling that was needed?” To this question, respondents selected one or more of the fifteen following reasons: (1) Cost too much, (2) No insurance, (3) Health plan problems, (4) Can’t find provider who accepts child’s insurance, (5) Not available in area/transport problems, (6) No convenient times/could not get appointment, (7) Provider did not know how to treat or provide care, (8) Dissatisfaction with provider, (9) Did not know where to go for treatment, (10) Child refused to go, (11) Treatment is ongoing, (12) No referral, (13) Lack of resources at school, (14) Neglected or forgot appointment, (15) Vaccine shortage, or (16) Other. For the purposes of this study, the “Vaccine Shortage” response was excluded as not applicable. Additionally, because the focus of the current study was to understand barriers to care for families not accessing services, “Treatment is ongoing” was also excluded. Exclusion was based on the premise that this selection suggested the family was accessing mental health services.

Construction of child need variables, EBDP and Condition Severity, is also detailed in Table 1. To assess the presence of an EBDP, the survey asked, “Does your child have any kind of emotional, developmental, or behavioral problem for which they need treatment or counseling?” and “Has the child’s emotional, developmental or behavioral problem lasted or is it expected to last 12 months or longer?” If the family answered yes to both questions, they were coded as having an EBDP. Condition Severity was measured through the survey question, “During the past 12 months how often has your child’s medical, behavioral, or other health conditions/emotional, developmental, or behavioral problems affected his/her ability to do things other children his/her age do?” If the caregiver responded “never” or “sometimes”, Condition Severity was coded as “0”. If they responded “usually” or “always”, the child was coded has having a severe condition.

The structure and description of child and family predisposing and enabling characteristic variables are provided in Table 1 as well. Child’s race is coded as white (reference group), Black only, Hispanic – Black or white, or Other. Child’s sex is coded as male (reference group) or female. Family income is coded as at or below 199% of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) (reference group) or at or above 200% FPL. Insurance type included private (reference group), public, both public and private, other or uninsured. Continuous health coverage and having a source of usual health care was coded as binary: the reference group did not have continuous health coverage and did not have a source of usual health care. Parent education, parent language, household structure, and urban/rural state residence was also binary—with English language, less than high school, less than two adults in the household, and rural state residence serving as the reference groups.

State Variables

State level variables controlling for the enabling factor of local mental health infrastructure include the total State Mental Health Authority (SMHA) Expenditures per Capita and the the total number of mental health facilities in the state. SMHA annual expenditures per capita were drawn from the Centers for Mental Health Services (CMHS) 2009 Uniform Reporting System to account for variation in state investment in mental health care. The total number of mental health organizations and providers was drawn from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive’s (SAMHDA) 2010 National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010).

Analysis

Descriptive analyses identified ratios of observations with key characteristics by EBDPs status and by year. Bivariate analysis was used to assess the proportion of each population with reported unmet family mental health need that reported each type of barrier to family mental health services. Proportions were observed separately for the total sample, for each year of data collection, and for both CSHCN with and without EBDPs. Uncorrected Pearson’s chi-squared statistics were used to assess significant differences in rates of reported barriers between years and between CSHCN groups.

After assessing bivariate associations between key barriers and sample characteristics, state level variables, and survey years, three fixed effects logistic regression models were fitted for the subpopulation of CSHCN with reported family mental health need (n = 8996). Each model estimated the association between need, predisposing, and enabling child, family, and state factors, year, and reported cost barriers (model 1), service time barriers (model 2), and location or transportation barriers (model 3). In these models, EBDPs is a covariate, allowing this population to be compared to CSHCN with no EBDP in relation to the reported barriers to family mental health care. Survey year was also included as a covariate, to assess the significance of changes in rates of reported barriers to mental health care for family members between survey years. Models were fitted for the full sample and for two subpopulations—those with reported family mental health need and those with unmet family mental health need. All models were assessed for multicollinearity, specificity, and goodness-of-fit (Archer & Lemeshow, 2006). Models with the best fit are reported here. Survey sampling weights were used to adjust for the complex survey design. Analyses were conducted in Stata 16 MP.

Results

Descriptive analysis of sample characteristics in Table 2 are weighted national proportions that demonstrate that the majority of the sample are CSHCN with no EBDP, both in 2005/2006 and in 2009/2010. A smaller portion of CSHCN with EBDPs have private insurance when compared to the portion of CSHCN with no EBDPs. More parents of CSHCN with EBDPs report income below 200% of the FPL, less than a high school education, and less than two parents in a household compared to those with no EBDPs. A greater number of CSHCN with EBDPs are reported to have severe impairments compared to those with no EBDPs. A greater percentage of CSHCN with EBDPs report a perceived need for mental health services for family members (33% vs. 30%) and unmet need for mental health care for family members (7% vs. 10%) compared to CSHCN with no EBDPs (4% and 0-1%, respectively). Further, rates of perceived need for family mental health care and reported unmet family mental health need increased for CSHCN with EBDPs from 7% in 2005 to 10% in 2009. Rates of public insurance increased and private insurance decreased from 2005 to 2009 for both groups of CSHCN.

Table 3 reports the weighted proportion of families with unmet family mental health need, for each population and for each year, who reported each type of barrier to services. P-values for uncorrected Pearson’s chi-square statistic between groups, within and across years, are reported. With the exception of barriers related to lack of referrals for services reported in 2005/2006, families with a CSHCN with EBDPs reported encountering all types of barriers to services at significantly greater rates than families whose CSHCN had no EBDPs in both years (p < 0.001). Cost barriers to family mental health care were the most commonly reported barrier to service for all populations across all years (33.5%). Lack of insurance (15.9%), being unable to find a convenient time to access mental health care (12.3%), health plan problems (10.6%), and encountering transportation or service availability barriers to services (8.7%) were the next most frequently reported barriers to family mental health care.

Table 4 displays results of bivariate analysis of sample characteristics (predisposing, enabling, and need factors) and parent-reported cost, time, and location barriers to mental health care for family members of CSHCN. Child’s insurance type, health insurance coverage gaps, and household income were significantly associated with reported cost barriers, but not with service time or location barriers. Child race and parent education level were significantly associated with reports of encountering barriers related to cost and the timing of services. Urban or rural state residence was significantly associated with reports of service availability or transportation barriers to family mental health care.

Results from multivariable analyses regressing mental health service cost, time, and location barriers for all CSHCN with family mental health needs on predisposing, need, and enabling characteristics are presented in Table 5. Families of non-white CSHCN had reduced odds of encountering cost barriers to mental health services (Black Only OR = 0.44 [0.25, 0.76]; Hispanic OR = 0.51 [0.30, 0.88]; Other=0.46 [0.30, 0.70]), as did families with a publicly insured CSHCN (OR = 0.30, [0.20, 0.45]), and incomes above 200% of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) (OR = 0.53 [0.37, 0.76]). Families with gaps in health insurance coverage in the prior twelve months (OR = 2.80 [1.83, 4.29]) and parents with more than high school education (OR = 1.52 [1.01, 2.28]) had much greater odds of encountering cost barriers to mental health services. The odds of experiencing barriers to family mental health care due to inconvenient service times was greater in families with parents with more than a high school education (OR = 2.60 [1.56, 4.34]). Families with CSHCN with more severe conditions were marginally more likely to experience location or transportation barriers to family mental health services (OR = 2.02 [1.00, 4.08]), but those living in urban locations had significantly lower rates of reporting location or transportation barriers to care (OR = 0.44 [0.27, 0.72]). In 2009, compared to 2005, families of CSHCN had notably higher rates of reporting all three barriers to family mental health services: cost barriers (OR = 1.89 [1.45, 2.46]), inconvenient service times (OR = 2.03 [1.34, 3.10]), and service availability or transportation barriers (OR = 2.24 [1.44, 3.47]).

Discussion

This is the first study to report nationally representative information about parent-reported barriers to mental health services for family members of CSHCN. It also reports child, family, and contextual factors associated with common structural barriers to family mental health services in the United States for CSHCN. Cost and insurance-related barriers were the most commonly reported obstacle to family mental health services for all CSHCN, followed by inconvenient service times and locations. Results also reveal that the rates of reported cost, service time, and service location or availability barriers was significantly higher in 2009 compared with 2005. CSHCN’s race, continuity and type of insurance, and parent education and income levels were factors associated with cost barriers to family mental health care. Parent education level was associated with increased rates of reported scheduling problems, and a CSHCN’s residence in an urban area was associated with reduced reports of service location or availability barriers.

Common barriers reported here reflect factors included in the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg et al., 2000) and themes described in other studies regarding obstacles to family support services, including insurance-related and financial concerns (Graaf et al., 2021; Inkelas et al., 2007, Lutenbacher et al., 2005; Pilapil et al., 2017). Also consistent with prior research, lack of information and inconvenient location and scheduling were commonly reported problems (Devine et al., 2016; Lutenbacher et al., 2005; Pilapil et al., 2017). Descriptive findings are also consistent with existing research establishing that, among families of CSHCN, those with a child with an EBDP report greater perceived need for family mental health services, as well as greater unmet need for family mental health care (Graaf et al., 2021; Inkelas et al., 2007). This study also found that families of CSHCN with EBDPs reported almost all types of barriers to family mental health care at much greater rates than CSHCN with no EBDPs. However, when other demographic factors were controlled for, EBDPs were not significantly associated with cost, service time, or location or transportation barriers. It should be noted, however, that having a child with a more severe condition was marginally associated with experiencing location or transportation barriers for families.

Because the NS-CSHCN has been discontinued, and the more recent National Survey of Children’s Health no longer collects information about family mental health care for families of CSHCN, the data used in this study are over ten years old. As such, findings may look different if assessed with more recent data due to expansions of insurance coverage and increased mental health parity mandates issued under the Affordable Care Act (Mechanic & Olfson, 2016). However, because relatively little is known about barriers that families of CSHCN face in accessing mental health care for themselves, and no studies have presented nationally representative data on the topic, these findings make several new contributions to the knowledge base about the mental health service access experiences of these families. Results provide national rates of a wide range of reported mental health access barriers for families of CSHCN. Further, this study illustrates that significant changes in family experiences with obstacles to accessing care can happen when observed over a four-year period.

Results suggest that families of CSHCN living in states with more rural areas are more likely to encounter problems with local service availability and transportation in accessing family mental health care. This is consistent with much literature reporting associations between rural residence and greater rates of unmet mental health care need for children (Duncan et al., 2020), and expands this assessment to include family members of children with complex health needs. Rural settings experience consistent shortages of behavioral health providers (Cherry et al., 2017, Graves et al., 2020; Larson et al., 2016; Thomas et al., 2009). These shortages are expected to worsen as demand for behavioral health care grows in response to higher rates of health coverage and increased behavioral health benefits resulting from the Affordable Care Act (Health Resources and Services Administration et al., 2015).

Finally, this study provides additional information about the role of health insurance in helping families to access mental health care. Though prior studies have found that a CSHCN’s type of health insurance does not significantly impact rates of unmet family mental health need (Graaf et al., 2021; Inkelas et al., 2007), findings here illustrate that families of publicly insured CSHCN have lower rates of reporting cost-related barriers to mental health care. Among publicly insured CSHCN, family members may also be covered by and financially eligible for public insurance. Public insurance, which has been linked to reduced rates of unmet mental health care needs for CSHCN themselves (Graaf & Snowden, 2019), may also be easing access to mental health care for family members. Alternatively, if family members are privately insured but the CSHCN is publicly insured through Medicaid waiver programs for children complex health needs, families may have greater access to mental health supports provided through specialized Medicaid waiver programming (Graaf & Snowden, 2017).

Implications for Practice and Policy

Recent calls to assertively address mental health concerns for parents of CSHCN highlights the value of enhancing access to effective interventions to support families (Biel et al., 2020). In light of this need, a practical implication of this study stands out in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic and related economic crisis: Insurance and cost-related barriers are significant for families seeking mental health services and are likely to increase in times of national economic strain. Though service accessibility normally increases as mental health systems expand and improve over time (Mark et al., 2011), rates of reported cost, location, and service time barriers to family mental health care increased significantly from 2005 to 2009. However, the 2009/2010 data were collected during one of the most substantial economic recessions in United States history—thus, findings of change over time may be capturing the national impacts of the Great Recession. The normative trajectory of growth and progress in mental health service may have been muted by the retrenchment in public human services (Graaf et al., 2016) and reductions in employer-sponsored health coverage suffered by millions of families across the United States during the Great Recession (Cawley et al., 2015; Hurd & Rohwedder, 2010; Yilmazer et al., 2015).

From 2005 to 2009, need for family mental health services decreased, but rates of unmet need increased. This is particularly relevant to current events, as millions of American families with CSHCN have experienced economic hardships and decreased social and educational support brought about by the COVID 19 pandemic (Pecor et al., 2021). It is likely that unmet need for family mental health care is increasing during this crisis, and policies and interventions that eliminate cost barriers and increase flexibility in mode and timing of service delivery may help to mitigate this. In particular, even outside of pandemic conditions, providers offering virtual mental health care may increase access to mental health care for families.

Virtual counseling services have been demonstrated to be successful in overcoming timing and service availability barriers related to childcare and transportation (Chen et al., 2020). Establishing satellite offices and offering services during non-traditional business hours may also help to address these barriers. Finally, professionals on the care team for a CSHCN can help to reduce cost and information barriers to mental health care by screening for mental health needs in family members and providing information on local mental health resources. Referrals should be made to safety net mental health services that provide services on a sliding scale or at no cost, along with information regarding how to access these services. In follow up appointments, providers can check in with family members on whether their needs are being met and further problem solve with them regarding access to services.

Research Implications

Since 2009, federal health policy has further advanced coverage for mental health services by expanding health insurance coverage and implementing the Essential Health Benefits (EHB) mandate under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010. The effects of these policies would likely be reflected in lower national rates of reported insurance and cost-related barriers to family mental health services in post-ACA estimates if this study were conducted with more recent data. However, the impacts of the ACA’s insurance expansions and EHB mandate on CSHCNs' family mental health care is currently unknowable at the national level.

The National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs has been discontinued and the current National Survey of Children’s Health, from 2016 to 2021, excludes assessment of need and unmet need for family mental health care as well as specific parent-reported barriers to particular health care services. The exclusion of this topic since the implementation of the ACA precludes any possibility of examining the impacts of the ACA on the mental health or other health care access experiences of parents and siblings of CSHCN. Inclusion of these survey questions in future iterations of the NSCH will be critical to tracking the effects of these and future health policy changes on the accessibility of a wide range of health care services for families of CSHCN.

Though generalizability to the current behavioral health care landscape may be limited until national health surveys opt to re-incorporate information about need for family support services and specific barriers to these services, study findings highlight the need for continued investigations of health care needs of caregivers and siblings of CSHCN. Much research reports on the strain experienced by CSHCN’s caregivers (Brannan et al., 2018; Green et al., 2020), but assessments of interventions aimed at reducing strain are few. Broader investigations of both formal and informal resources and interventions—at the family, community or policy level—that reduce caregiver strain and associated mental distress are needed.

The barriers reported in this study primarily encompass system-level barriers to mental health care, but other studies of behavioral health care barriers point to the role that perceptions of both mental health problems and mental health providers may play in preventing mental health care access (Owens et al., 2002). Wider understanding of obstacles to mental health care related to perceptions of mental health problems or mental health providers may uncover perspectives unique to the experiences of these families that can be addressed through individual or community-level interventions. Understanding the unique experiences of these families, and how they contribute to unmet need, may indicate that mental health needs may be prevented or more effectively met through less formal systems—such as parent peer support groups (January et al., 2016) or wraparound interventions targeting activation of families’ natural supports in their extended family, churches, or neighborhoods (Olson et al., 2021).

These approaches may require community-level assessments and interventions to increase physical and psychological integration of these children and their families. This may involve efforts to reduce stigma (McKeague et al., 2021) and physical barriers to community participation for families of CSHNC (Kraemer et al., 1997). Expanding availability of resources that can aid in mobility and integration—such as mobility or communication aids for CSHCN or accessible public transportation—may also be important (Bigby et al., 2019, Sze & Christensen, 2017). Policy interventions, such as mandated health insurance coverage or public funding for these activities and supports can advance these objectives. Investments in less formal helping systems may also help to address behavioral health workforce shortages that continue to grow, particularly in rural communities (Thomas, et al., 2009).

Limitations

This study is limited by the use of parent-reported survey data, which can be imprecise due to inaccuracies in recall (Hoagwood et al., 2000). Further, the use of secondary data limits assessment of family experiences of barriers to mental health care not included in the survey questionnaire. In particular, the survey excludes barriers related to perception of mental health services or mental health problems, which are also factors known to prevent individuals and families from utilizing mental health services (Owens et al., 2002). While some of these barriers may have been captured in the “other” variable, the exclusion of more specific barriers related to perception of mental health or mental health services constrains study implications to primarily structural interventions. Finally, to fully assess the impacts of the ACA, other mental health parity legislation, and federal, state and local efforts to expand access to mental health care for CSHCN family members, nationally-representative data about family mental health access and barriers to care in the post-ACA era are needed.

References

Aguilar, B., O’Brien, K. M., August, G. J., Aoun, S. L., & Hektner, J. M. (2001). Relationship quality of aggressive children and their siblings: A multi-informant, multi-measure investigation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29(6), 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1012273024211.

Andersen, R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137284.

Archer, K. J., & Lemeshow, S. (2006). Test for a logistic regression model fitted using survey sample data. The Stata Journal, 6(1), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0600600106.

Biel, M. G., Tang, M. H., & Zuckerman, B. (2020). Pediatric mental health care must be family mental health care. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(6), 519–520. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0065.

Bigby, C., Johnson, H., O’Halloran, R., Douglas, J., West, D., & Bould, E. (2019). Communication access on trains: A qualitative exploration of the perspectives of passengers with communication disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1380721.

Blumberg, S. J., Welch, E. M., Chowdhury, S. R., Upchurch, H. L., Parker, E. K., & Skalland, B. J. (2008). Design and operation of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2005-2006 (pp. 1–188). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_01/sr01_045.pdf.

Bramlett, M. D., Blumberg, S. J., Ormson, A. E., George, J. M., Williams, K. L., Frasier, A. M., Skalland, B. J., Santos, K. B., Vsetecka, D. M., Morrison, H. M., Pedlow, S., & Wang, F. (2014). Design and operation of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2009-2010 (pp. 1–271). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_01/sr01_057.pdf.

Bramlett, M. D., Read, D., Bethell, C., & Blumberg, S. J. (2009). Differentiating subgroups of Children with Special Health Care Needs by health status and complexity of health care needs. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13(2), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0339-z.

Brannan, A. M., Brennan, E. M., Sellmaier, C., & Rosenzweig, J. M. (2018). Employed parents of children receiving mental health services: Caregiver strain and work–life integration. Families in Society, 99(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044389418756375.

Caicedo, C. (2014). Families with special needs children: Family health, functioning, and care burden. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 20(6), 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390314561326.

Cawley, J., Moriya, A. S., & Simon, K. (2015). The impact of the macroeconomy on health insurance coverage: Evidence from the Great Recession. Health Economics, 24(2), 206–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3011.

Chen, J. A., Chung, W.-J., Young, S. K., Tuttle, M. C., Collins, M. B., Darghouth, S. L., Longley, R., Levy, R., Razafsha, M., Kerner, J. C., Wozniak, J., & Huffman, J. C. (2020). COVID-19 and telepsychiatry: Early outpatient experiences and implications for the future. General Hospital Psychiatry, 66, 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.07.002.

Cherry, S., Robinson, A., Jashinsky, J., Bagwell-Adams, G., Elliott, M., & Davis, M. (2017). Rural community health needs assessment findings: Access to care and mental health. Journal of Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences, 11(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.5590/JSBHS.2017.11.1.18.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2005). National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN) (SPSS/SAS/Stata/CSV) Constructed Data Set Cooperative Agreement U59MC27866; Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). www.childhealthdata.org.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2009). National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN) (SPSS/SAS/Stata/CSV) Constructed Data Set Cooperative Agreement U59MC27866; Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). www.childhealthdata.org.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2012). 2009-2010 NS-CSHCN Indicator and Outcome Variables SPSS Codebook, Version 1. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI). (2019). 2016-2017 National Survey of Children’s Health (2 Years Combined Data Set): Child and Family Health Measures, National Performance and Outcome Measures, and Subgroups, SPSS Codebook, Version 1.0. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). www.childhealthdata.org.

Derigne, L., Porterfield, S., & Metz, S. (2009). The influence of health insurance on parent’s reports of children’s unmet mental health needs. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13(2), 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0346-0.

Devine, K. A., Manne, S. L., Mee, L., Bartell, A. S., Sands, S. A., Myers-Virtue, S., & Ohman-Strickland, P. (2016). Barriers to psychological care among primary caregivers of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(5), 2235–2242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3010-4.

Duncan, L., Georgiades, K., Reid, G. J., Comeau, J., Birch, S., Wang, L., & Boyle, M. H. (2020). Area-level variation in children’s unmet need for community-based mental health services: Findings from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(5), 665–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01016-3.

Ganz, M. L., & Tendulkar, S. A. (2006). Mental health care services for children with special health care needs and their family members: Prevalence and correlates of unmet needs. Pediatrics, 117(6), 2138–2148. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-1531. hch.

Gelberg, L., Andersen, R. M., & Leake, B. D. (2000). The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research, 34(6), 1273–1302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307080612.

Ghandour, R. M., Perry, D. F., Kogan, M. D., & Strickland, B. B. (2011). The medical home as a mediator of the relation between mental health symptoms and family burden among children with special health care needs. Academic Pediatrics, 11(2), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2010.12.015.

Graaf, G., Annis, I., Martinez, R., & Thomas, K. C. (2021). Predictors of unmet family support service needs in families of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Maternal and Child Health Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03156-w.

Graaf, G., Hengeveld-Bidmon, E., Carnochan, S., Radu, P., & Austin, M. J. (2016). The impact of the Great Recession on county human-service organizations: A cross-case snalysis. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2015.1124820.

Graaf, G., & Snowden, L. (2017). The role of Medicaid home and community-based service policies in organizing and financing care for children with severe emotional disturbance. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.007. psyh.

Graaf, G., & Snowden, L. (2018). Medicaid waivers and public sector mental health service penetration rates for youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(5), 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000295.

Graaf, G., & Snowden, L. (2019). Public health coverage and access to mental health care for youth with complex behavioral healthcare needs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00995-2

Graves, J. M., Abshire, D. A., Mackelprang, J. L., Amiri, S., & Beck, A. (2020). Association of rurality with availability of youth mental health facilities with suicide prevention services in the US. JAMA Network Open, 3(10), e2021471. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21471.

Green, A. L., Kutash, K., Ferron, J., Levin, B. L., Debate, R., & Baldwin, J. (2020). Understanding caregiver strain and related constructs in caregivers of youth with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(3), 761–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01626-y.

Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of Policy, Planning, and Innovation. (2015). National Projections of Supply and Demand for Selected Behavioral Health Practitioners: 2013-2025 (p. 35). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hoagwood, K., Stiffman, A., Rae, D., & Bickman, L. (2000). Concordance between parent reports of children’s mental health services and service records: The Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA). Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026492423273.

Hurd, M. D., & Rohwedder, S. (2010). Effects of the Financial Crisis and Great Recession on American Households (Working Paper No. 16407; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w16407.

Inkelas, M., Raghavan, R., Larson, K., Kuo, A. A., & Ortega, A. N. (2007). Unmet mental health need and access to services for children with special health care needs and their families. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 7(6), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ambp.2007.08.001.

January, S. A., Duppong Hurley, K., Stevens, A. L., Kutash, K., Duchnowski, A. J., & Pereda, N. (2016). Evaluation of a community-based peer-to-peer support program for parents of at-risk youth with emotional and behavioral difficulties. Journal of Child and Family Studies; New York, 25(3), 836–844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0271-y.

Jensen, E. J., Mendenhall, T., Futoransky, C., & Clark, K. (2021). Family medicine physicians’ perspectives regarding rural behavioral health Care: Informing ideas for increasing access to high-quality services. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-021-09752-6.

Kilmer, R. P., Cook, J. R., Munsell, E. P., & Salvador, S. K. (2010). Factors associated with positive adjustment in siblings of children with severe emotional disturbance: The role of family resources and community life. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(4), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01050.x.

Kraemer, B. R., Blacher, J., & Marshal, M. P. (1997). Adolescents with severe disabilities: Family, school, and community integration. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 22(4), 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/154079699702200410.

Larson, E. H., Patterson, D. G., Garberson, L. A., & Andrilla, C. H. A. (2016). Supply and Distribution of the Behavioral Health Workforce in Rural America (Data Brief #160). Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington. https://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/09/RHRC_DB160_Larson.pdf

Lutenbacher, M., Karp, S., Ajero, G., Howe, D., & Williams, M. (2005). Crossing community sectors: Challenges faced by families of children with special health care needs. Journal of Family Nursing, 11(2), 162–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840705276132.

Mark, T. L., Levit, K. R., Vandivort-Warren, R., Buck, J. A., & Coffey, R. M. (2011). Changes In US spending on mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1986–2005, and implications for policy. Health Affairs, 30(2), 284–292. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0765.

McKeague, L., Hennessy, E., O’Driscoll-Lawrie, C., & Heary, C. (2021). Parenting an adolescent who is using a mental health service: A qualitative study on perceptions and management of stigma. Journal of Family Issues, 0192513X211030924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211030924.

Mechanic, D., & Olfson, M. (2016). The Relevance of the Affordable Care Act for Improving Mental Health Care. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 515–542. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-092936.

Nageswaran, S., Parish, S. L., Rose, R. A., & Grady, M. D. (2011). Do children with developmental disabilities and mental health conditions have greater difficulty using health services than children with physical disorders? Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(5), 634–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0597-4.

Nygård, C., & Clancy, A. (2018). Unsung heroes, flying blind—A metasynthesis of parents’ experiences of caring for children with special health-care needs at home. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(15–16), 3179–3196. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14512.

Olson, J. R., Benjamin, P. H., Azman, A. A., Kellogg, M. A., Pullmann, M. D., Suter, J. C., & Bruns, E. J. (2021). Systematic review and meta-analysis: Effectiveness of Wraparound Care Coordination for children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.02.022.

Owens, P., Hoagwood, K., Horwitz, S. M., Leaf, P. J., Poduska, J., Kellam, S. G., & Ialongo, N. (2002). Barriers to children’s mental health services. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(6), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200206000-00013.

Pecor, K. W., Barbayannis, G., Yang, M., Johnson, J., Materasso, S., Borda, M., Garcia, D., Garla, V., & Ming, X. (2021). Quality of Life Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic for Caregivers of Children with ADHD and/or ASD. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073667.

Pilapil, M., Coletti, D. J., Rabey, C., & DeLaet, D. (2017). Caring for the caregiver: Supporting families of youth with special health care needs. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 47(8), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2017.07.003.

Roberts, T., Miguel Esponda, G., Krupchanka, D., Shidhaye, R., Patel, V., & Rathod, S. (2018). Factors associated with health service utilisation for common mental disorders: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 262. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1837-1.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2010 Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/dataset/national-mental-health-services-survey-2010-n-mhss-2010-ds0001.

Sze, N. N., & Christensen, K. M. (2017). Access to urban transportation system for individuals with disabilities. IATSS Research, 41(2), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iatssr.2017.05.002.

Thomas, K. C., Ellis, A. R., Konrad, T. R., Holzer, C. E., & Morrissey, J. P. (2009). County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 60(10), 1323–1328. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1323.

Vohra, R., Madhavan, S., Sambamoorthi, U., & St Peter, C. (2014). Access to services, quality of care, and family impact for children with autism, other developmental disabilities, and other mental health conditions. Autism, 18(7), 815–826. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313512902.

Wei, X., & Yu, J. W. (2012). The concurrent and longitudinal effects of child disability types and health on family experiences. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(1), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0711-7.

Yilmazer, T., Babiarz, P., & Liu, F. (2015). The impact of diminished housing wealth on health in the United States: Evidence from the Great Recession. Social Science & Medicine, 130, 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.028.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to Publish/Participate

Due to the use of publicly available survey data, this study did not require IRB approval or informed consent of participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Graaf, G., Baiden, P., Keyes, L. et al. Barriers to Mental Health Services for Parents and Siblings of Children with Special Health Care Needs. J Child Fam Stud 31, 881–895 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02228-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02228-x