Abstract

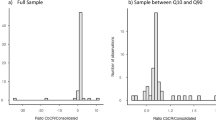

In trying to explain the drivers of global profit shifting by multinational enterprises (MNEs), we investigate firm-specific determinants and their variation across major industries. Using the ORBIS database, we show that intangible asset endowment of subsidiaries and the supply-chain complexity of MNE groups explain aggregate profit-shifting trends. According to our estimates, subsidiaries with no intangibles react to an incremental increase of the tax rate by reducing reported profits by 0.76 %, while subsidiaries with above median intangible endowment decrease their profits by 1.2 %. This difference is significant at the 5 % level. We find an even more pronounced difference in the observed semi-elasticities comparing affiliates belonging to simple (\(-\)0.52) and more complex MNEs (\(-\)1.92), suggesting a significantly larger sensitivity to CIT rate changes of the latter group. Moreover, we incorporate country-specific transfer pricing mitigation measures (documentation requirements) into our analysis. We find significant mitigation effects, which vary depending on the drivers identified in our analysis. On average, estimated profit shifting among MNE subsidiaries in our sample is reduced by 52 % 2 years after the introduction of mandatory documentation requirements. We do, however, not find a significant effect on affiliates with high intangible endowments, whereas documentation reduces profit shifting of subsidiaries within complex MNE groups. Our analysis suggests that complexity poses less of a challenge to effective domestic enforcement than the appropriate pricing of intangible assets. These findings thus provide additional insights on profit-shifting risks and mitigation effects conditional on firm attributes, which may support the design of anti-avoidance approaches and help guide the allocation of scarce analytical and enforcement resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See OECD (2013).

See United Nations (2013).

Similar to sector and sub-sector analysis which is commonly used to inform domestic tax administration risk assessment studies.

For an early approach differentiating industries, see Bartelsman and Beetsma (2003).

For a recent overview on intangibles and growth, see Andrews and Serres (2012).

OECD Revised Guidance in June 2012 http://www.oecd.org/tax/transfer-pricing/50526258.

The OECD extended its transfer pricing guidelines regarding business restructurings in 2010.

These typically include internal financial service providers, marketing activities, management services, and the tax function; all potential sources of profit shifting. Arguably, multi-product MNEs derive some of their competitive advantages from these back-office functions, including more advantageous holding arrangements in low and no-tax jurisdictions, more sophisticated internal process management, and financing schemes.

See Ribeiro et al. (2010) for a comprehensive summary.

For a detailed discussion of the balance sheet item intangible fixed asset, see Dischinger and Riedel (2011)

Negative entries for number of employees, fixed assets, etc.

The broadest sample specification, consisting of around 25,000 affiliates and 130,000 observations, is used as part of our robustness checks.

Based on this narrower definition of a group, we exclude MNEs that are not operating in at least two countries.

Heckemeyer and Overesch (2012) find that transfer pricing is the main profit-shifting channel.

Specifically, the tax differential is calculated as the difference between the country’s tax rate where a subsidiary is located to the unweighted average of other relevant tax rates.

The conditional semi-elasticity is given by \(\partial \ln (\pi )/\partial \tau =\alpha +\varvec{\beta }_2\varvec{x}\); we expect \(\varvec{\beta }_2<0\).

Both \(\beta _3=0\) and \(\beta _3<0\) are possible candidates for affiliates with \(\tau <0\). On the one hand, if reported profits are already inflated, then firm behavior might be unaffected by the introduction of documentation requirements. On the other hand, perceived risk of penalization linked to newly introduced documentation rules may further increase the incentives to shift profits into the country.

We also tested for other interactions but did not find any significant results. For clarity, we omit these interactions in the specification above.

A table with detailed descriptive statistics is provided in Annex 2.

We also tested a specification allowing for an interaction between our drivers and the tax differential. The corresponding coefficient was not significant.

As a size measure, we take the centered logarithm of the MNE’s total assets.

Following Desai et al. (2006), we also tested a differentiation of large and small haven jurisdictions without noting any meaningful impact on our results.

For a detailed discussion of the balance sheet item intangible fixed asset, see Dischinger and Riedel (2011).

We estimated the unrestricted model with all possible interactions, but report only those that were significant.

In the specification presented in Column (2) of Table 5, five coefficients are relevant for estimating the effect documentation requirements have on the elasticity of taxable profits. We allow these to differ between subsidiaries with high (low) intangible intensity and high (low) complexity, respectively. This adds ten interaction terms. In addition, we test whether the two-way interaction between complexity and intangible intensity with documentation related variables (adding another five interactions) helps explain variation in our observations. The hypothesis that the corresponding coefficients are mutually zero can not be rejected (Wald-test: \(\chi ^2(5)=1.57, p>0.1\)).

Results of this estimation are reported in Table 8 in the Annex.

Although the empirical part concentrates on total linkages, described below, all results are robust to using direct instead of total linkages.

The rationale behind this expression is that a unit increase in final demand will require an additional \(A\) units of intermediate inputs \(x\) to be produced. In order to produce \(A\) units of the intermediate inputs, another \(A^2\) units are necessary, and so on. Therefore, total activity increases by \(I+A+A^2+\cdots =(I-A)^{-1}\) units.

References

Andrews, D. & Serres, A.D. (2012). Intangible assets, resource allocation and growth: A framework for analysis. OECD Economics Department Working Paper 989, OECD Publishing.

Bartelsman, E. J., & Beetsma, R. M. W. J. (2003). Why pay more? corporate tax avoidance through transfer pricing in OECD countries. Journal of Public Economics, 87(9–10), 2225–2252.

Becker, J., & Riedel, N. (2012). Cross-border tax effects on affiliate investment: Evidence from european multinationals. European Economic Review, 56(3), 436–450.

Beuselinck, C., Deloof, M., Vanstraelen, A. (2009). Multinational income shifting, tax enforcement and firm value. Working Paper 12/27, University of Tilburg.

Desai, M. A., Foley, C. F., & Hines, J. J. (2006). The demand for tax haven operations. Journal of Public Economics, 90(3), 513–531.

Dischinger, M., & Riedel, N. (2010). The role of headquarters in multinational profit shifting strategies. Working Paper 1003, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation.

Dischinger, M., & Riedel, N. (2011). Corporate taxes and the location of intangible assets within multinational firms. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 691–707.

Ghosh, A. (1958). Input–output approach in an allocation system. Economica, 25(97), 58–64.

Grubert, H. (2003). Intangible income, intercompany transactions, income shifting, and the choice of location. National Tax Journal, 56(1), 221–42.

Heckemeyer, J., & Overesch, M. (August 2012). 2012. Profit shifting channels of multinational firms: A meta-study. Paper presented at IIPF Congress.

Hines, J. R., & Rice, E. M. (1994). Fiscal paradise: Foreign tax havens and american business. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(1), 149–182.

Hirschman, A. O. (1958). The strategy of economic development. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Huizinga, H., & Laeven, L. (2008). International profit shifting within multinationals: A multi-country perspective. Journal of Public Economics, 92(5–6), 1164–1182.

Karkinsky, T., & Riedel, N. (2012). Corporate taxation and the choice of patent location within multinational firms. Journal of International Economics, 88(1), 176–185.

Lenzen, M. (2003). Environmentally important paths, linkages and key sectors in the australian economy. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 14(1), 1–34.

Leontief, W. W. (1936). Quantitative input and output relations in the economic systems of the United States. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 18(3), 105.

Lohse, T., & Riedel. N. (2012). The impact of transfer pricing regulations on profit shifting within european multinationals. FZID Discussion Paper 61–2012, University of Hohenheim, Center for Research on Innovation and Services (FZID).

Lohse, T., Riedel, N., Spengel, C. (2012). The increasing importance of transfer pricing regulations: A worldwide overview. Working Paper 1227, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation.

Maffini, G., & Mokkas, S. (2009). Profit shifting and measured productivity of multinational firms. Working Paper 0920, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation.

OECD. (2013). Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Rasmussen, P. (1956). Studies in Intersectoral Relations. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Ribeiro, S.P., Menghinello, S., Backer, K.D., (2010). The OECD ORBIS database: Responding to the need for firm-level micro-data in the OECD. OECD Statistics Working Paper 2010/1, OECD Publishing.

United Nations. (2013). Practical manual on transfer princing for developing countries. New York: United Nations.

Weichenrieder, A. J. (2009). Profit shifting in the EU: Evidence from germany. International Tax and Public Finance, 16(3), 281–297.

World Bank. (2014). forthcoming. World Bank: Transfer Pricing ToolKit.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers, participants of the DIBT research seminar at the Vienna University of Economics and Business, participants of the annual doctoral meeting at the Centre for Business Taxation of the University of Oxford, as well as participants of the Investment Climate Department research workshop on business taxation at the World Bank for their helpful comments. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed to the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries which they represent. Financial support from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF: W 1235-G16) is gratefully acknowledged. All remaining errors and inaccuracies are, of course, our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Measuring supply-chain complexity

To quantify cross-border supply-chain complexity, we build on the notion of inter-industry linkages introduced by Rasmussen (1956).Footnote 27

Using Input–Output tables, provided by Eurostat, we calculate the \(N \times N\) matrix

of direct requirement coefficients \(a_{ij}\), with economy-wide output across \(N\) sectors denoted by the \(N \times 1\) vector \(x\). The variable \(X_{ij}\) depicts intermediate use of sector \(i\)’s outputs for the production process of sector \(j\). Assuming a linear production function, the direct input requirements thus expresses the share of good \(j\) that is produced by intermediate inputs from industry \(i\). The column sums of \(A\) are thus a simple measure of direct linkages between industry \(j\) and the rest of the economy.Footnote 28

A measure that captures the cascading demand effect of increasing production, first developed by Leontief (1936), is given by so-called total linkages. In the static Leontief model, the most common application of Input–Output tables, the total output is related to the vector of final demand \(y\) by

where the \(N \times N\) matrix \(B=\{b_{ij}\}\), called the Leontief-inverse, captures the economic dynamics in response to a change in final demand.Footnote 29 Specifically, additional economy-wide activity that is induced by a demand shock in sector \(j\) is given by the \(j\)’th column sum \(B_{j}=\sum _{i=1}^{n} b_{ij}\) of the Leontief inverse.

As discussed above, we hypothesize that transfer (mis)pricing risks of a subsidiary are increasing in the scale of the MNE group’s cross-border linkages. Denoting the set of different industries within MNE \(k\) that are located in country H by \(\mathcal {I}_{H,k}\), and the set of different industries within the same group that are located abroad by \(\mathcal {I}_{-H,k}\), we define total backward cross-boarder linkages for affiliates in country H and MNE \(k\) by

Given that cross-border activity may also be driven by supply shocks, we calculate forward linkages, which are based on the Ghosh-model (Ghosh 1958), a supply-driven analog to the Leontief model. Our calculations follow the approach illustrated above, but rely on the direct sales coefficients \(\tilde{a}_{ij}=X_{ij}/x_i\). Forward linkages are thus represented by row sums \(\tilde{B}_{i.}=\sum _j \tilde{b}_{ij}\) of the Gosh-inverse \(\tilde{B}=(I-\tilde{A})^{-1}\). We define total forward cross-border linkages within MNE \(k\) and country H, analogously, by

Our proxy for the complexity of the supply chain is given by the sum of forward and backward cross-border linkages

Appendix 2: Descriptive statistics

See Table 7.

Appendix 3: Mitigation regression

See Table 8.

Appendix 4: Documentation requirements: detailed description

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beer, S., Loeprick, J. Profit shifting: drivers of transfer (mis)pricing and the potential of countermeasures. Int Tax Public Finance 22, 426–451 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-014-9323-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-014-9323-2