Abstract

The rise of misinformation on social media platforms is an extremely worrisome issue and calls for the development of interventions and strategies to combat fake news. This research investigates one potential mechanism that can help mitigate fake news: prompting users to form implementation intentions along with education. Previous research suggests that forming “if – then” plans, otherwise known as implementation intentions, is one of the best ways to facilitate behavior change. To evaluate the effectiveness of such plans, we used MTurk to conduct an experiment where we educated participants on fake news and then asked them to form implementation intentions about performing fact checking before sharing posts on social media. Participants who had received both the implementation intention intervention and the educational intervention significantly engaged more in fact checking behavior than those who did not receive any intervention as well as participants who had received only the educational intervention. This study contributes to the emerging literature on fake news by demonstrating that implementation intentions can be used in interventions to combat fake news.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The spread of fake news, particularly on social media platforms, is a matter of significant public concern as it affects societies in several ways. This has included the circulation of factually dubious articles presented as if from verified and credible sources, which emerged as a major issue during the 2016 US presidential election. Previous research evaluating the dissemination of such fake news articles estimated that the average American encountered between one and three fake news stories during the month before the presidential election (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). Such use of fake news as a political weapon highlights the threat it poses to democracy. Additionally, misleading information about products can have dire financial consequences for organizations. In 2016, when a fake news story about Pepsi’s CEO telling Trump supporters to “take their business elsewhere” went viral, the company’s stock fell about 4% (Berthon et al., 2018). Unverified and false information can also affect life and death when it interferes with medical decisions. A recent example of this is the COVID – 19 pandemic which has given rise to a plethora of misinformation such as using bleach on food or gargling with bleach to kill the virus. A survey conducted in May 2020, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found 39% of respondents had misused cleaning products (Gharpure, 2020). Considering the above events, it has become essential to develop interventions aimed at reducing the spread of fake news.

The term “fake news” refers to fabricated content or misleading information presented as if from legitimate sources (Lazer et al., 2018). Fake news imitates media content without following journalism’s accuracy and credibility standards. Reducing the proliferation of fake news is a major challenge. Educating users about the dangers of sharing unverified and false content on social media is obviously part of the solution for combating fake news. Research supports educating users to recognize fake news as an effective solution. This approach is both theoretical and practical. However, nascent research suggests that educational interventions are unlikely to reduce the spread of misinformation when used solely, and must be combined with other interventions to improve their effectiveness (Guess et al., 2020; Shyh et al., 2023).

What is needed to combat fake news is to: (1) build an understanding of what fake news is, (2) develop the motivation to not share unverified and misleading content, (3) understand the mechanisms of how to evaluate the accuracy and credibility of online information, and (4) implement those mechanisms when sharing information on social media platforms. Fortunately, one of the best ways to enable goal attainment is to use implementation intentions (Gollwitzer, 1993). The relatively simple act of declaring “If situation Y is encountered, then I will initiate goal-directed behavior X.” generates automaticity for obtaining goal-directed behavior X (Gollwitzer, 1993; Sheeran et al., 2006; Orbell et al., 1997; Prestwich et al., 2008; Webb & Sheeran, 2003; Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006). Implementation intentions can be enacted in many ways, including written (Duckworth et al., 2011), verbal (Gollwitzer & Brandstätter, 1997) and checklists (Armitage, 2016). This creates an opportunity for social media platforms to take advantage of implementation intentions in reducing the spread of fake news as well as mitigating its effects. Therefore, the research question we would like to investigate in this study is: 1) Can implementation intentions be used to mitigate the effects of fake news? To answer the question, we mainly draw from the theories of goal attainment behavior and implementation intentions. We suggest that implementation intentions can be utilized in many ways to combat fake news. Some examples follow. An implementation intention of the form “If I want to read a story on social media, then I will check that it comes from a mainstream news source” can be used to increase users’ reliance on high quality sources and prevent exposure to fake news. An implementation intention of the form “If I want to share a story on social media, then I will make sure that it comes from a mainstream news source” can be used to prevent the retransmission of fake news. Similarly, an implementation intention of the form “If I want to share a story on social media, then I will check its validity on a fact checking website like factcheck.org” can be used to improve users’ engagement in fact checking behavior. We emphasize that asking users to form implementation intentions is a simple and direct intervention for social media platforms to employ on top of other practices currently utilized as it can help combat fake news.

To evaluate if implementation intentions can be utilized to combat fake news, we conducted experiments using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. In the experiments, we first educated participants on fake news and then asked them to form implementation intentions about performing fact-checking before sharing posts on social media. Several studies have found that people heed factual information, even when it is not consistent with their beliefs (Fridkin et al., 2015; Wood & Porter, 2019), however, some studies suggest that fact checking has a minimal impact (Lewandowsky et al., 2012) and sometimes might even backfire (Pluviano et al., 2019). In this study, we do not concern ourselves with the effects of fact checking behavior but focus on whether implementation intentions can be utilized to combat fake news. More specifically, we use implementation intentions in combination with education. We evaluate the effectiveness of such a hybrid intervention towards improving engagement in fact checking and compare it with education alone and a control group that did not receive any intervention.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, we review prior literature on mechanisms that can slowdown the spread of fake news and mitigate its effects. To put this literature in perspective, we classify interventions and strategies used to counter the spread of misinformation into two groups: platform centric interventions and user centric interventions. Second, we describe our theoretical background on goal attainment explaining how education and implementation intentions aid in the realization of goals. Third, we present our hypotheses. Fourth, we elaborate on the method used to test the hypotheses and discuss the results. Finally, we conclude by discussing implications for theory and practice.

2 Literature Review

People increasingly obtain news and civic information through social media platforms. According to the Pew Research Center, 47% of Americans report using social media platforms, with Facebook being the most dominant platform, as their main source of news (Gottfried & Shearer, 2017). This trend shifts the responsibility of evaluating the quality of information and the credibility of the sources from newsroom editorial boards to social media platforms and their users. The structure of social media platforms plays an important role in how information is disseminated throughout their websites. Typically, the flow of information on these platforms is based on how users are interconnected and their past behaviors (Bakshy et al., 2015). This leads to the creation of “echo chambers” where users are largely exposed to information that conforms with their existing opinions (Modgil et al., 2021) and “filter bubbles” in which algorithms frequently feed information based on users’ past behaviors (Flaxman et al., 2016). Previous research shows that people prefer information that is consistent with their existing opinions leading them to accept such information uncritically (Garrett & Weeks, 2013; Flynn et al., 2017). This is a consequence of confirmation bias. Repeated exposure to information can also increase its acceptance (Lewandowsky et al., 2012). Recent research has suggested that misinformation travels at a much faster rate than verified and true information due to a novelty effect (Vosoughi et al., 2018). This clearly suggests that echo chambers and filter bubbles can amplify the effects of misinformation. Social media platforms can improve the information environment by reducing echo chambers and filter bubbles while emphasizing the quality of information. Social media platforms can also help reduce the spread of fake news by making changes to their environments that help users better evaluate information they encounter. Several strategies have been developed based on the concept of nudging which suggests that subtle changes in the choice architecture, i.e., the decision-making environment, can alter people’s behavior in predictable ways without sacrificing their freedom of choice (Leonard, 2008) (Thaler and Sunstein 2008). In other words, strategies based on nudges leverage knowledge of how people make decisions and the various cognitive biases that they are susceptible to in order to minimize the spread of fake news (Konstantinou et al., 2019; Lewandowsky et al., 2017). Nudges can take many forms including warnings, reminders, and recommendations. Overall, we find that countermeasures that can be utilized to slowdown the dissemination of fake news and mitigate its effects can be broadly categorized into two groups: (1) platform centric and, (2) user centric.

2.1 Platform Centric Interventions

Platform centric interventions work behind the scenes with the primary goal of limiting the exposure of users to fake news in the first instance (Lazer et al., 2018). Such interventions require social media platforms to proactively monitor and sort information posted on their websites in order to detect fake news. Misinformation detection mechanisms can be either manual or algorithmic. Platform centric interventions can be further classified into the following two groups: (1) sorting interventions and, (2) filtering interventions.

Sorting interventions are based on sorting strategies, i.e., the systematic categorization of content into groups. For example, an intervention involving the preferential display of news from trustworthy sources to users relies upon the social media platform’s algorithmic ranking of content based on source quality. Similarly, platforms can deprioritize shares and posts that most readers skip over or skim quickly so that it is less likely to appear in the news feeds.

Filtering interventions utilize filtering techniques to improve the information environment. This includes excluding selective information from certain categories (for example, excluding information disseminated by bots from trending topics), retracting fake news that violates the policies of the social media platform (for example, removing posts that contradict information released through official channels), and removing or banning user accounts that actively spread misinformation. Some filtering interventions utilize mechanisms that can be used to detect and remove malicious bots and information posted by such bots. Bots are software-controlled accounts that automatically disseminate information and can be tailored to target specific users or user groups (Shao et al., 2018). These accounts function in the same way as legitimate users by posting content and interacting with other users. However, not all bots are malicious. Social media platforms can use bots to quickly disseminate valuable information. This provides hope for developing positive interventions that utilize bots.

Social media platforms have attempted to adopt the above discussed interventions. For example, in March 2020, Twitter (now X) expanded its misinformation policies to remove statements that contradict guidelines issued by public health authorities from its platform (Roth & Pickles, 2020). Following the 2016 presidential election, both Facebook and Twitter deleted hundreds of thousands of posts associated with Russian trolls (Popken, 2018). In May 2020, Twitter provided information to refute two of President Trump’s posts about mail-in voting that falsely claimed that California was sending ballots to anyone living in the state (Qiu, 2020). However, the extent to which these interventions are effective is not clear as the platforms have not released enough information for the research community to evaluate.

2.2 User Centric Interventions

User centric interventions are interventions that attempt to slowdown the proliferation of fake news by influencing the decision-making processes of the users (Lewandowsky et al., 2012; Soetekouw & Angelopoulos, 2022). User centric interventions are of several types: (1) debunking interventions, (2) inoculation interventions, (3) educational interventions, (4) informative interventions, (5) prescriptive interventions.

Debunking interventions work towards correcting fake news that have taken root. Fact checking falls under this category. Fake news can be debunked by explaining the flawed arguments they contain, providing alternative explanations and contextual information when possible. Previous research suggests that debunking misinformation can backfire unless used in conjunction with providing alternative explanations (Ecker et al., 2014; Zimet et al., 2013). People actively develop mental models of events and occurrences and a retraction of information creates a gap in their mental model. People prefer inconsistent mental models than incomplete mental models. Previous research has also found that alternative explanations are more effective when they conform with preexisting beliefs held by users (Kahan, 2017). Therefore, providing alternative explanations is not only essential but is more effective when information is framed in such a way that it aligns with the worldview of targeted users. People tend to accept familiar information as true (Schwarz et al., 2007; Swire & Ecker, 2018). Debunking interventions can also backfire due to a familiarity effect when they repeat initial misinformation in order to correct it (Schwarz et al., 2007).

Inoculation interventions aim to reduce susceptibility to fake news by exposing them to small amounts of misinformation (Roozenbeek et al., 2020, Van der Linden et al., 2017, Cook et al., 2017). Rooted in the social-psychological theory of attitudinal inoculation, these interventions work on the mechanism of pre-bunking, i.e., presenting users with examples of misinformation and rebuttal of that misinformation, creates attitudinal resistance against similar misinformation (Van der Linden et al., 2017). In simple words, “If you can recognize it, you can resist it”, is the principle these interventions are based on. Inoculation interventions also help users discover and learn how to identify fake news from true news by themselves. A great example of this is the Bad News game which allows players to take on the role of a propagandist, i.e. someone who spreads misinformation. The aim of the game is to gather as many followers as possible without losing too much credibility. Players can build their own army of trolls, spread their own messages, and influence public opinions. This allows players to gain insight into the strategies used by real world fake news mongers (Roozenbeek et al., 2020).

Educational interventions aim to elevate the information literacy of the users (as well as moderators and administrators of social media platforms) (Lutzke et al., 2019; Kim & Dennis, 2019). Examples of such interventions include educating users about the harms of misinformation and strategies used to verify information and identify high-quality sources. Educational interventions facilitate behavior change through the formation of goal intentions and improvement in attitude towards the intended behavior. This suggests that informing users about the malicious effects of spreading unverified or false information should lead to the formation of intentions to not share such information. Additionally, training people how to evaluate the quality of information and its source should enable them to make better decisions about sharing information (Murrock et al., 2018). Meta (2020) implemented an educational intervention that provides users with tips on how to spot fake news that includes investigating links and sources, checking the evidence and dates, and approaching articles with a skeptical frame-of -mind.

Informative interventions aim at enabling users to better evaluate the quality of information they encounter by providing warnings and labels. These interventions work by altering outcome expectations (Chen et al., 2015). The concept of outcome expectations is based on social cognitive theory and refers to one’s beliefs regarding the possible consequences of performing a behavior (Bandura, 1986). The theory suggests that people will perform behaviors that produce positive outcomes and avoid behaviors that produce negative outcomes. Therefore, changing users’ outcome expectations can deter them from sharing fake news. Social media platforms have only recently begun to adopt such measures. For example, in May 2020, Twitter launched labels for synthetic and manipulated media, along with a rubric to assess tweets’ misinformation risk (Roth & Pickles, 2020). This evaluation includes color codes for misleading, disputed, and unverified claims, categorized as moderate or severe. Previous research suggests that warnings reduce the effects of misinformation but do not entirely eliminate the continued influence effect (Ecker et al., 2010). The continued influence effect states that people continue to use retracted misinformation, even when they remember the retraction, to make inferences (Johnson & Seifert, 1994). Recent research has found that attaching warnings to fake news headlines also creates an implied truth effect which enhances the perceived accuracy of headlines without warnings (Pennycook et al., 2020b).

Prescriptive interventions are interventions that encourage people to rethink their behavior by providing explicit recommendations, which is the focus of this paper. Examples include recommending users to read the article before sharing and asking users to fact-check information. Similarly, asking users to form actions plans and implementation intentions to reduce spreading fake news are also prescriptive interventions. Social media platforms have started to test prescriptive intervention-based features recently. For example, Twitter has come out with a new prompt which asks users if they would like to read an article first before retweeting it (Hern, 2020) that shows some success at getting the articles to be read more before being tweeted (Bell, 2020). Social media platforms could similarly nudge users toward forming implementation intentions. An example mockup of how a social media site can do so is shown below in Fig. 1.

A summary of the interventions discussed above is presented in Table 1.

The literature discussed above points to several interventions and strategies to combat fake news. We find that research has evaluated the effectiveness of only a few of the interventions discussed above. This is the first study that we know of to suggest implementation intentions as a possible mechanism for interventions to combat fake news. In this study, we investigate the effectiveness of a hybrid intervention involving implementation intentions and education in improving engagement in fact checking and compare it with the effectiveness of education alone as well as a control group that did not receive any interventions. Insights gleaned from this study can also aid in the development of similar other hybrid interventions.

3 Theoretical Foundations

3.1 Goal Attainment

Goal attainment has been investigated as an “attitude to behavior” concept (Fazio, 1986), with three main phases of attitude-behavior research identified. The first phase focused on the question of whether “attitude to behavior” relationships exist at all, i.e. the “is” question of existence. While this research found a lot of supportive evidence, many studies also failed to show a direct connection between attitude and behavior (Acock and DeFleur, 1972, LaPiere, 1934, Wicker, 1969, DeFleur and Westie, 1958). Building on the above foundation, traditional theories of goal attainment such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) suggested that attitudes towards a behavior, alongside subjective norms and perceived behavioral control (in the case of TPB), contribute significantly to the formation of behavioral intentions (Ajzen, 1985; Bandura, 1977; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). This intention is a crucial predictor of actual behavior, establishing that before an individual engages in a behavior, there exists an intention formation phase where attitudes significantly influence the individual’s intention to perform or not perform that behavior.

The second phase of research expanded the scope to examine the effects of various moderating factors such as situational factors and personality variables on the attitude-behavior dynamic (Acock and DeFleur, 1972, Weissberg, 1965). This phase significantly advanced our understanding of the role of personality factors (self-image, self-monitoring, moral reasoning), normative constraints, specificity, confidence, etc. as moderators. The culmination of this research phase presented a nuanced view of the attitude-behavior relationship emphasizing the importance of context and individual differences.

In the third phase, the focus shifted to the processes underlying attitude-behavior congruence. Fazio (1986) highlighted the automatic processes of accessible attitudes towards respective objects and events, which assured attitude-congruent behaviors towards them. This phase contributed critical insights into the mechanics of how attitudes guide behavior, reinforcing the complex interplay between various psychological processes and behavioral outcomes.

3.2 Education

As explained above, intention is an immediate precursor of actual behavior. One way to help individuals form intentions about a behavior is to provide them with information about why to perform a behavior and how to perform the behavior. Educating individuals about the advantages of performing a behavior and the disadvantages of not performing the behavior leads to an improvement in attitudes towards the behavior (Lutzke et al., 2019; Murrock et al., 2018). Educational interventions, thus, can serve as a potent tool in this process by leveraging the provision of information to influence behavior through the improvement of attitudes towards the intended behavior and the formation of goal intentions. Educational interventions can be designed to target specific behaviors and are tailored to address the needs and concerns of the target audience. For instance, educational interventions might focus on the importance of vaccination, providing factual information about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, as well as countering misinformation, to encourage vaccination uptake.

3.3 Implementation Intentions

Continuing with the third phase of attitude-behavior research, but with a focus on intention-behavior relationships, Gollwitzer (1993) introduced the concept of implementation intentions. Implementation intentions can be defined as “if – then” plans aimed at forming a link between a conditional situation and a goal-directed behavioral response (Gollwitzer & Brandstätter, 1997). The Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior highlight that intention is a good predictor of behavior (Ajzen, 1985; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Implementation intentions go a step further. When someone plans using the format “If I encounter situation Y, I will do action X,” they are more likely to act than if they just intend to achieve X. In other words, intentions focus on desired outcomes or goals to which individuals feel committed (Gallo et al., 2012; Gollwitzer, 1993), whereas implementation intentions focus on linking a specific cue or cues to an intended behavior (Gollwitzer & Brandstätter, 1997). This approach is based on the rubicon model of action phases which distinguishes between motivational and volitional phases of action (Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987). Motivation is a pre-decisional state whereas volition is a post-decisional state. Individuals form intentions and prepare to perform the behavior in the volitional state. It is during this phase that implementation intentions are critical. Previous research has investigated the effect of implementation intentions on goal attainment in several domains including attainment of personal goals (Koestner et al., 2002), control of stereotypical beliefs (Gollwitzer et al., 2002), health related behaviors (Milne et al., 2002; Sheeran & Orbell, 2000; Verplanken & Faes, 1999), and travel behaviors (Bamberg, 2000). The increase in effectiveness of behavior for implementation intentions versus intentions alone is summarized by Gollwitzer and Sheeran (2006) in a meta-analysis of 94 studies and finds a medium-to-large magnitude for effect size (d = 0.65).

Implementation intentions operate by reducing the gap between intentions and the attainment of behavior. The psychological mechanisms underlying implementation intentions include: (1) an increase in the mental accessibility of cues that activate the intended behavior obtained by clearly specifying the cue (Sheeran et al., 2006; Webb & Sheeran, 2008) and, (2) the automatic activation of the intended behavior when the specified cues are encountered (Gallo et al., 2012; Sheeran et al., 2006). Although the act of forming implementation intentions is a deliberate and conscious act, the mechanism by which implementation intentions operate is automatic (Webb & Sheeran, 2008). This is achieved by making explicit the link between a specific outcome and a specific cue or cues (Sheeran et al., 2006; Gollwitzer & Brandstätter, 1997; Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006; Bargh, 1992). Doing so also removes the need to deliberate over which response to pursue upon encountering the cue, making the execution of the intended behavioral response effortless and automatic (Webb & Sheeran, 2007).

4 Hypotheses

The extant literature reinforces the notion that education is an important solution to combating fake news and mitigating its effects. Education equips users with the knowledge, skills and tools that are needed to help them recognize fake news (Roozenbeek and Van der Linden, 2019, Lutzke et al., 2019, Kim & Dennis, 2019). When people are educated about the characteristics of fake news and the tactics commonly used to spread fake news, they become more capable of recognizing fake news articles. This in turn reduces their susceptibility to falling for fake content. Moreover, education can lead to a decrease in the likelihood of individuals sharing fake news on social media, thus curbing the propagation of fake news (Lutzke et al., 2019; Murrock et al., 2018). However, recent research has expressed concerns that education alone is insufficient to combat fake news. For example, after learning different strategies on how to identify fake news, more than 20% of people still rated fake news as “somewhat accurate” or “very accurate” (Guess et al., 2020). Another recent study found that educational interventions were ineffective in helping participants determine the authenticity of information (Shyh et al., 2023). Therefore, alongside our investigation into the effectiveness of implementation intentions in addition to education, we also explore and draw comparisons with the sole impact of education in combating fake news. For this purpose, we utilize a brief educational intervention which involves informing users about what fake news is, and a few strategies that can be utilized to verify the credibility of information and the information source. Such an intervention should help users identify fake news as they form intentions about verifying information before sharing stories on social media platforms. Based on the above, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

Users receiving the educational intervention, i.e., suggestions on how to validate information, will engage in fact checking behavior more than users who do not.

As explained earlier, implementation intentions are “if – then” plans that forge a link between a specific cue and an intended behavioral response. They can serve as a potent tool to combat fake news by creating a clear and actionable plan for individuals when they encounter potentially false information online. For instance, consider the following implementation intention: “If I want to share a story on social media, then I will check its validity on Snopes.com.” This if-then plan creates a direct link between the intention to share a story and the necessary action of fact-checking. When individuals encounter a news story they are inclined to share, this implementation intention prompts them to pause and verify its accuracy on a fact checking website like Snopes.com. By incorporating implementation intentions into their online behavior, individuals are more likely to act on their intention to verify information before sharing it. This approach may help to counter the rapid spread of fake news because it introduces a deliberate step that encourages critical thinking and fact-checking behavior. It serves as a mental reminder and a commitment to responsible information sharing, thereby contributing to a healthier online information ecosystem and mitigating the influence of fake news.

Snopes is a popular fact checking platform that classifies all claims/stories into four categories: false, true, ambiguous, or uncertain. Snopes.com is a signatory of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) code of principles (Poynter Institute, n.d.). The IFCN aims to protect the value and credibility of fact checking tools by ensuring that fact checking remains objective and rigorous. The IFCN code of principles is a series of commitments that member organizations abide by to promote excellence in fact checking (Poynter Institute, n.d.). To be deemed compliant with the IFCN code of principles, an organization must exhibit a commitment to nonpartisanship and fairness, transparency of sources, transparency of funding and organization, transparency of methodology, and a commitment to open and honest corrections. For this reason, prominent platforms such as Google and Facebook now prefer fact checks produced by signatories of the IFCN code of principles (Poynter Institute, n.d.). Snopes is verified to be compliant with IFCN standards.

In previous studies, implementation intentions have been operationalized in several ways. Armitage (2007) instructed participants to form plans about how to perform a behavior (which in their case was to quit smoking). Participants were free to choose how to perform the behavior but were told to pay particular attention to the situations in which they would implement their plans. Duckworth et al. (2011) operationalized implementation intentions by asking users to identify cues related to the behavioral response and then asked participants to fill out an “if…, then…” template. Armitage (2016) altogether dropped the planning instruction and operationalized implementation intentions in the form of checklists by asking participants to match an if statement with an appropriate then statement. Webb and Sheeran (2003) operationalized implementation intentions by asking participants to whisper a pre-specified implementation intention to themselves.

In this study, we operationalized implementation intentions in a typed form. We asked participants to type a pre-specified “if – then” plan which linked the cue of sharing a story on social media and the behavior of fact checking the story before sharing it (i.e., “If I want to share a story on social media, then I will check its validity on snopes.com”). This typed implementation intention form is similar to the pre-specified verbal implementation intention as used by Webb and Sheeran (2006). We used this form of implementation intentions as it can be easily implemented by social media platforms. The implementation intention intervention used in this study should lead to automatic fact checking behavior when users want to share stories on any social media platform. Based on this, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

Users who form implementation intentions in addition to receiving the educational intervention will engage in fact checking behavior more than users who do not.

Educational interventions are used in many scenarios; however, they are often combined with additional interventions as education alone may not suffice to bring about behavioral change. While an educational intervention influences behavior due to the formation of goal intentions (Koestner et al., 2002), a prescriptive intervention that recommends users to form “if – then” plans will tend to have a more pronounced effect on behavior owing to the principle of automaticity (Gollwitzer, 1993; Sheeran et al., 2006; Prestwich et al., 2008).

In the context of fake news, educational interventions primarily focus on improving users’ accuracy of detecting false or misleading information. Detection, however, does not have a major impact on information sharing as users may be influenced by other social media factors such as whether sharing will attract and please their friends and followers (Pennycook et al., 2020a). Therefore, we extended the educational intervention in this study as it allows for a critical situation (i.e., the sharing of a potentially fake news article) to link to the initiation of an intended behavior (i.e., checking the article on snopes.com). Participants receiving only the educational intervention will form goal intentions about fact checking whereas participants who are asked to form implementation intentions after receiving the educational intervention will obtain automaticity for performing fact checking when sharing stories on social media. Such implementation intentions will also remove the need to deliberate over which action to pursue (such as whether to share the story or not) and makes performing the fact checking behavior effortless. Based on the above, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Users who form implementation intentions in addition to receiving the educational intervention will engage in fact checking behavior more than users who receive only the educational intervention.

5 Methodology

The goal of this paper is to test if implementation intentions can be utilized to combat fake news. We specifically test the effectiveness of implementation intentions in the context of improving users’ engagement in fact checking behavior and compare how implementation intentions perform as compared to an educational intervention. To gain a suitable pool of participants, an initial pre-experiment survey was conducted on MTurk to gather 200 qualified participants to invite for the experimental groups. The pre-experiment survey was used to find self-identified high to low social media content-sharing users on a five-point Likert scale. Demographic information was also collected using the pre-experiment survey. Self-identified low or no content sharing users were excluded from the follow-up experiment. The initial pre-experiment survey paid $0.15 and included two screening check questions which resulted in an initial response of 562 MTurkers to identify 200 follow-on participants.

The 200 moderate and above content-sharing users were then invited to participate in the follow-up experiment with two randomly assigned conditions: education and implementation intentions. Both conditions were given a presentation about the definition of fake news, and its main characteristics and tips on identifying fake news which included checking the story on fact-checking website such as snopes.com. Specifically, participants had to read the following information.

What is fake news?

Fake news is fabricated content or misleading information presented as if from legitimate sources. Fake news mimics news media content in form but is information that does not follow the standard editorial norms and processes of journalism for ensuring the accuracy and credibility of information.

To control/prevent spreading fake news:

-

Be skeptical of headlines. False news stories often have catchy headlines in all caps with exclamation points. If shocking claims in the headline sound unbelievable, they probably are.

-

Look closely at the URL (website address/link). A phony or lookalike URL may be a warning sign of false news. Many false news sites mimic authentic news sources by making small changes to the URL. You can go to the site to compare the URL with established sources.

-

Investigate the source. Ensure that the story is written by a source that you trust with a reputation for accuracy. If the story comes from an unfamiliar organization, check their “About” section to learn more. Additionally, check the source or the story on a fact verification site, such as snopes.com.

-

Inspect the dates. False news stories may contain timelines that make no sense, or event dates that have been altered.

-

Look at other reports. If no other news source is reporting the same story, it may indicate that the story is false. If the story is reported by multiple sources that you trust, it’s more likely to be true.

The above presentation represented the education portion of the experiment. The implementation intentions condition was then presented with an image of the following statement (thus not allowing for users to cut and paste their response), “If I want to share a story on social media, then I will check its validity on snopes.com.” and asked to type that into a response box. Typing the “if – then” plan was how implementation intentions were operationalized. If the typed response did not match verbatim, the user was allowed one more chance to get it correct, and then the experiment was complete. Because of potential minor inaccuracies that could occur (such as lower case vs. upper case letters), responses were manually checked to see if a valid implementation intention had been entered by the user for follow-on data analysis. The education group received only the education portion of the experiment and a check question about ways to limit the spread of fake news. Participants were told that based upon their responses, they could be invited back for a follow-up survey with three $25 bonus payments available. These participants were paid $0.50 for this experiment, and of the 200 participants contacted, 70 valid responses were received for the implementation intentions group and 57 valid responses were received for the education group in the post-experiment follow up.

One week after completing the experimental phase, participants received a follow-up survey inquiring about the frequency of considering sharing stories on social media within the past five days. They were also asked how many of these stories were checked for validity on sites like snopes.com. Additionally, we also asked participants how many stories were ultimately shared. Valid responses received for each group were: education – 32, implementation intentions – 37. Participants were paid $0.20 and were part of the lottery for the three $25 bonus payments, regardless of whether they submitted a valid response or not.

Immediately after completing the experimental phase (within 48 h) and identifying the valid experimental response pool size, we set up a combined survey of demographics and questions regarding sharing and fact-checking behavior on social media over the past five days. The aim was to obtain a targeted pool of 40–50 control group participants. The sharing and fact checking questions were self-report data. Self-report data has been shown to be valid in various contexts, including alcohol and drug use (Del Boca and Noll, 2000), the presence of hypertension (Vargas et al., 1997), and smoking behavior (Wong et al., 2012 ). The data was collected anonymously, and was recent in recall, which contributes to the likelihood of receiving valid self-reports. The survey also included two check questions and the content-sharing five-point Likert scale question. 145 participants were gathered, resulting in 41 valid control responses. This survey paid $0.20 and had its own $25 dollar lottery bonus payment. Demographic information is shown below in Table 2.

6 Results

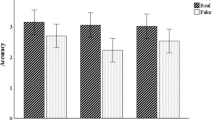

All variables of interest were normally distributed, independent, and met Levene’s test of homogeneity of variance (p > .05). A one-way between-subjects ANOVA was conducted to compare the effect of control, education, and implementation intentions on getting participants to check the validity of stories on social media before sharing them, and on the resulting sharing of stories. There was a significant effect of treatment, i.e., implementation intentions, on the percentage of stories fact checked at the p < .05 level for the three conditions [F(2, 107) = 4.519, p = .013]. Post Hoc comparisons using Fisher’s LSD test indicated that the mean percentage shared for the implementation intentions plus education condition (M = 45%, SD = 40.5) was significantly different than the education only condition (M = 21.8%, SD = 23.8) and the control condition (M = 25.2%. SD = 32.7). Therefore, hypotheses 2 and 3 were supported. There was no significant difference between the control condition and education only condition. Therefore, hypothesis 1 was not supported.

Additionally, there was no significant difference in the percentage of stories shared between the three conditions. Age was also significantly different between the control condition (M = 33.9, SD = 10.9) and implementation intentions condition (M = 27.8, SD = 5.2), but not between the education condition (M = 31.6, SD = 9) and either of the others. A univariate general linear model was analyzed with age as a control factor and age was found to be not significant overall (p > .05). Gender and number of stories considered to be shared during the previous five days were also not significantly different between groups. Descriptive statistics for the number of articles that were considered sharing are shown in Table 3. Descriptive statistics for the number of articles that were fact checked on sites similar to snopes.com and the number of articles that were ultimately shared on social media are shown below in Table 4.

Taken together, these results suggest that implementation intentions when used on top of education significantly improved engagement in fact checking behavior before sharing, but education alone did not. Also, no difference was found in the number of stories shared regardless of education or implementation intention to check the validity of stories before sharing. Overall, hypothesis 1 was not supported whereas hypotheses 2 and 3 were supported.

7 Conclusion

In this study, we investigated if implementation intentions and education can be utilized to improve users’ engagement in fact checking behavior. Several studies have found that people heed factual information, even when it is not consistent with their beliefs (Wood & Porter, 2019; Fridkin et al., 2015). However, some studies suggest that fact checking has a minimal impact (Lewandowsky et al., 2017) and sometimes might even backfire (Pluviano et al., 2019). In this study, we do not concern ourselves with the effects of fact checking behavior but instead focus on testing whether implementation intentions can be utilized to combat fake news. Specifically, we investigated if implementation intentions when combined with education improve engagement in fact checking behavior. We measured the effect of our hybrid intervention on participants one week after they had received an educational intervention and had formed implementation intentions, and found supporting evidence that implementation intentions can be utilized to combat fake news. Our results indicated that participants who had formed implementation intentions in addition to receiving the educational intervention performed fact checking more than participants who had not as well as participants who received only the educational intervention. Additionally, as evident by the results, merely educating users about fake news is not enough.

On one hand, we were surprised to find that the educational intervention on fake news, which included suggestions for users on how to verify information and its source, had no effect on participants’ fact-checking behavior one week after the intervention. This finding might be attributed to the knowledge-action gap which can arise due to several reasons. In other words, there is often a gap between what people know and what they do, also known as the knowledge-action gap (Sniehotta et al., 2005). Individuals may understand the importance of fact-checking and the detrimental effects of fake news but fail to translate this knowledge into consistent action. This gap can result from various factors, including lack of motivation, perceived effort involved in fact-checking, or simply forgetting to apply the knowledge in relevant situations. On the other hand, following our expectations, we observed a positive effect of our hybrid intervention which combined implementation intentions with education on enhancing engagement in fact-checking behavior. Such a positive effect on behavior can be attributed to the principle of automaticity on which implementation intentions work. Consistent with previous research, this study highlights the efficiency of implementation intentions in bridging the intention-behavior gap.

The results of our experiment suggest that educational interventions need to be combined with other types of interventions to have a lasting positive effect on users. Future research may examine the effects of hybrid interventions (combinations of two or more interventions) on users to determine efficient strategies that facilitate behavior change to mitigate fake news. The effectiveness of implementation intentions can vary over time, and it often depends on the specific behavior and an individual’s commitment to maintaining the intended action. In the short term, implementation intentions can have a strong impact on behavior. When the intention is fresh and motivation is high, implementation intentions can be particularly effective. However, over a more extended period, the effect of implementation intentions may weaken if individuals do not consistently reinforce the link between the situational cue and the intended behavior. Motivation and commitment can also fluctuate, affecting the likelihood of following through with the intended action. To maintain the long-term effectiveness of implementation intentions, individuals may need periodic reminders, self-monitoring, or additional strategies to help sustain their commitment to the specified behavior. Future research may look into how the effectiveness of implementation intentions varies over time and how implementation intentions can be strengthened.

Although not hypothesized, we measured the groups’ article sharing, suspecting fact-checking might reduce overall shares if some were false. However, results suggest otherwise. There are several possible reasons for this. First, users may be habituated to share a certain number of stories every day. Second, fact checking may encourage users to share links to facts as a way to warn their friends of misinformation. Third, the number of stories containing misinformation encountered on social media platforms during the experiment period may be very low. Further research is needed to evaluate the full effects of implementation intentions on the retransmission of fake news. One important note here is that sharing is not the only type of behavior that contributes to fake news retransmission. Other activities such as commenting or liking of an article also increase the likelihood of that article appearing in others’ feeds.

Based on the findings of our study, we developed the following recommendations for social media platforms and users. By adopting these recommendations, social media platforms and users can work together to mitigate the spread of fake news and foster a more responsible and informed online environment.

Recommendations for Social Media Platforms:

-

1.

Incorporate Implementation Prompts: Social media platforms can integrate features that encourage users to create implementation intentions for responsible sharing. For example, when users are about to share content, the platform can prompt them with questions such as, “Are you sure you have fact-checked this information?” or “Have you considered the source’s credibility?” This is similar to Twitter’s “Want to read this before Retweeting?” prompt which pops up when a user did not open an article on Twitter’s platform before retweeting it.

-

2.

Educational Resources: Social media platforms can provide users with educational resources and tips on how to create implementation intentions for responsible sharing. Offer guidance on identifying misinformation and reliable fact-checking sources.

-

3.

Fact Checking Integration: Social media platforms can integrate fact checking tools directly into the platform. This allows users to fact-check content easily before sharing it.

-

4.

User Behavior Tracking: Social media platforms can monitor user behavior patterns and provide feedback on users’ sharing habits. This feedback can include personalized suggestions for more responsible sharing based on users’ previous actions.

-

5.

Algorithmic Adjustments: Social media platforms can adjust their algorithms to prioritize content from trusted sources and reduce the visibility of potentially false or misleading information. Furthermore, the platforms may consider transparency of their algorithms to build user trust.

Recommendations for Users:

-

1.

Create Implementation Intentions: Users should proactively create their own implementation intentions for responsible sharing on social media. For example, “If I see a sensational headline, then I will fact-check the story before sharing it.“

-

2.

Use Fact Checking Resources: Users should familiarize themselves with reliable fact checking websites and tools.

-

3.

Verify Sources: Implementation intentions can also involve source verification. If users are not familiar with the source, then they should make it a habit to research the credibility of the source before sharing its content.

-

4.

Pause Before Sharing: Users can also create an implementation intention to pause for a moment before clicking the share button. Use this time to consider the information’s validity and whether it aligns with responsible sharing practices.

-

5.

Stay Up to Date: Users should continuously educate themselves about the latest trends in misinformation and media literacy. Being informed about common tactics used in spreading fake news can help make more informed decisions.

-

6.

Report Misinformation: When users encounter fake news, they should report it to the platform. Many social media platforms have mechanisms for reporting false or misleading content.

There are several limitations of this study. First, this study utilized self-reported measures. Self-reporting has been commonly used to test the effectiveness of implementation intentions in several studies (Koestner et al., 2002; Prestwich et al., 2008). Self-reported measures are said to suffer from social desirability bias (Durmaz et al., 2020; Larson, 2019). One common approach to mitigating social desirability bias is through ensuring anonymity (Grimm, 2010). In this study, we minimized the effects of social desirability bias through anonymizing our survey. Second, we did not tease out the individual effects of implementation intentions versus education. For participants in the implementation intention group, we first used education to enhance understanding of fact-checking’s importance. Then, we provided a practical framework for incorporating fact-checking into daily online behavior through implementation intentions. However, using the educational intervention prior to the implementation intention intervention may actually be considered a strength of the study, rather than a limitation. This is because in practical applications, it is common to combine various interventions and the lines between different interventions can often blur. Third, the final survey of the experiment received comparatively few participants than we had anticipated. Of the 200 participants that were invited to participate in the main experiment, only 69 participants successfully completed the follow-up survey. Future studies involving MTurk should have a more rigorous process to identify participants that are likely to complete all the way through the process before starting any experimental manipulations. Finally, there was no information gathered to determine the actual credibility of stories considered to be shared, nor the modification of sharing behavior on stories that were determined to be false when fact checked. Some expansions to this area of study would include gathering system level data before and after behavior, as well as system level and user level data on the sharing behavior of true and false stories after being fact checked. Additionally, the type and scope of training should be investigated for the theorized effect of education on fact checking behavior. The interventions we used were minor in both the presentation of the educational portion and the directed involvement in forming the implementation intention. While this does expose a potential weakness in education alone affecting fact checking behavior, it also portrays the power of implementation intentions on top of education to do so. Further research is needed to examine how long the effect of implementation intentions lasts on fact-checking and sharing behaviors. Finally, there are a variety of interventions and strategies that can be employed to combat fake news. While the study focused on two interventions, i.e., education and implementation intention interventions, it would certainly be valuable to explore a wider range of interventions in future research. This can help provide a more comprehensive understanding of which interventions are the most effective under different circumstances and for different target audiences.

This study contributes to the emerging literature on misinformation by demonstrating the effectiveness of implementation intentions in combating fake news. Additionally, our research suggests that brief educational interventions such as providing users with suggestions on how to verify information have minimal effects. This study also contributes to the existing literature on implementation intentions and goal attainment by introducing a simple way to operationalize implementation intentions, i.e., by asking users to type an already formed “if – then” plan and by showing the effectiveness of implementation intentions in the context of combating fake news.

Data Availability

The dataset analyzed for the current study is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SFQ35O.

References

Acock, A. C., & Defleur, M. L. (1972). A configurational approach to contingent consistency in the attitude-behavior relationship. American Sociological Review, 714–726.

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. Action control Springer.

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31, 211–236.

Arechar, A. A., Allen, J., Berinsky, A. J., Cole, R., Epstein, Z., Garimella, K., & Rand, D. G. (2023). Understanding and combatting misinformation across 16 countries on six continents. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(9), 1502–1513.

Armitage, C. J. (2007). Efficacy of a brief worksite intervention to reduce smoking: The roles of behavioral and implementation intentions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 376.

Armitage, C. J. (2016). Evidence that implementation intentions can overcome the effects of smoking habits. Health Psychology, 35, 935.

Bakshy, E., Messing, S., & Adamic, L. A. (2015). Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science, 348, 1130–1132.

Bamberg, S. (2000). The Promotion of New Behavior by forming an implementation intention: Results of a field experiment in the Domain of Travel Mode Choice 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 1903–1922.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986.

Bargh, J. A. (1992). The ecology of automaticity: Toward establishing the conditions needed to produce automatic processing effects. The American Journal of Psychology, 181–199.

Bell, K. (2020). Twitter says its test to get people to read articles before tweeting worked. Engadget [Online]. https://www.engadget.com/twitter-prompt-read-article-before-tweeting-191907421.html [Accessed August 6 2022].

Berthon, P., Treen, E., & Pitt, L. (2018). How truthiness, fake news and post-fact endanger brands and what to do about it. Marketing Intelligence Review, 10, 18–23.

Chen, X., Sin, S. C. J., Theng, Y. L., & Lee, C. S. (2015). Deterring the spread of misinformation on social network sites: A social cognitive theory-guided intervention. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 52, 1–4.

Cook, J., Lewandowsky, S., & Ecker, U. K. (2017). Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PloS one, 12.Del Boca, F. K., & Noll, J. A. (2000). Truth or consequences: the validity of self-report data in health services research on addictions. Addiction, 95(11s3), 347–360.

Defleur, M. L., & Westie, F. R. (1958). Verbal attitudes and overt acts: An experiment on the salience of attitudes. American Sociological Review, 23, 667–673.

Duckworth, A. L., Grant, H., Loew, B., Oettingen, G., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2011). Self-regulation strategies improve self‐discipline in adolescents: Benefits of mental contrasting and implementation intentions. Educational Psychology, 31, 17–26.

Durmaz, A., Dursun, İ., & Kabadayi, E. T. (2020). Mitigating the effects of social desirability bias in self-report surveys: Classical and new techniques. Applied social science approaches to mixed methods research. IGI Global.

Ecker, U. K., Lewandowsky, S., & Tang, D. T. (2010). Explicit warnings reduce but do not eliminate the continued influence of misinformation. Memory & Cognition, 38, 1087–1100.

Ecker, U. K., Swire, B., & Lewandowsky, S. (2014). Correcting misinformation—A challenge for education and cognitive science. Processing Inaccurate Information: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives from Cognitive Science and the Educational Sciences, 13–38.

Fazio, R. H. (1986). How do attitudes guide behavior. Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior, 1, 204–243.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

Flaxman, S., Goel, S., & Rao, J. M. (2016). Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80, 298–320.

Flynn, D., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2017). The nature and origins of misperceptions: Understanding false and unsupported beliefs about politics. Political Psychology, 38, 127–150.

Fridkin, K., Kenney, P. J., & Wintersieck, A. (2015). Liar, liar, pants on fire: How fact-checking influences citizens’ reactions to negative advertising. Political Communication, 32, 127–151.

Gallo, I. S., Mcculloch, K. C., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2012). Differential effects of various types of implementation intentions on the regulation of disgust. Social Cognition, 30, 1–17.

Garrett, R. K., & Weeks, B. E. (2013). The promise and peril of real-time corrections to political misperceptions. Proceedings of the conference on Computer supported cooperative work, 2013. 1047–1058.

Gharpure, R. (2020). Knowledge and practices regarding Safe Household Cleaning and Disinfection for COVID-19 Prevention—United States, May 2020. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). Goal achievement: The role of intentions. European Review of Social Psychology, 4, 141–185.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Brandstätter, V. (1997). Implementation intentions and effective goal pursuit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 186.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 69–119.

Gollwitzer, P., Achtziger, A., Schaal, B., & Hammelbeck, J. (2002). Intentional control of stereotypical beliefs and prejudicial feelings. Unpublished manuscript, University of Konstanz, Germany.

Gottfried, J., & Shearer, E. (2017). Americans’ online news use is closing in on TV news use. Pew Research Center, 7.

Grimm, P. (2010). Social desirability bias. Wiley international encyclopedia of marketing.

Guess, A. M., Lerner, M., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., & Sircar, N. (2020). A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and false news in the United States and India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117, 15536–15545.

Heckhausen, H., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1987). Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational versus volitional states of mind. Motivation and Emotion, 11, 101–120.

Hern, A. (2020). Twitter Aims To Limit People Sharing Articles They Have Not Read. The Guardian, June 11.

Johnson, H. M., & Seifert, C. M. (1994). Sources of the continued influence effect: When misinformation in memory affects later inferences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 20, 1420.

Kahan, D. M. (2017). Misconceptions, misinformation, and the logic of identity-protective cognition.

Kim, A., & Dennis, A. R. (2019). Says who? The effects of presentation format and source rating on fake news in social media. MIS Quarterly, 43.

Koestner, R., Lekes, N., Powers, T. A., & Chicoine, E. (2002). Attaining personal goals: Self-concordance plus implementation intentions equals success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 231.

Konstantinou, L., Caraban, A., & Karapanos, E. (2019). Combating Misinformation Through Nudging. IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Springer, 630–634.

Lapiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. actions. Social Forces, 13, 230–237.

Larson, R. B. (2019). Controlling social desirability bias. International Journal of Market Research, 61, 534–547.

Lazer, D. M., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., & Rothschild, D. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359, 1094–1096.

Leonard, T. C. (2008). In H. Richard, C. R. Thaler, & Sunstein (Eds.), Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Springer.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13, 106–131.

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the post-truth era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6, 353–369.

Lutzke, L., Drummond, C., Slovic, P., & Árvai, J. (2019). Priming critical thinking: Simple interventions limit the influence of fake news about climate change on Facebook. Global Environmental Change, 58, 101964.

Meta (2020, March 23). Tips to Spot False News [Facebook page]. Retrieved March 15, 2023 from https://www.facebook.com/formedia/blog/third-party-fact-checking-tips-to-spot-false-news.

Milne, S., Orbell, S., & Sheeran, P. (2002). Combining motivational and volitional interventions to promote exercise participation: Protection motivation theory and implementation intentions. British Journal of Health Psychology, 7, 163–184.

Modgil, S., Singh, R. K., Gupta, S., & Dennehy, D. (2021). A confirmation bias view on social media induced polarisation during Covid-19. Information Systems Frontiers, 1–25.

Murrock, E., Amulya, J., Druckman, M., & Liubyva, T. (2018). Winning the war on state-sponsored propaganda: Results from an impact study of a Ukrainian news media and information literacy program. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 10, 53–85.

Orbell, S., Hodgkins, S., & Sheeran, P. (1997). Implementation intentions and the theory of planned behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 945–954.

Pennycook, G., Bear, A., Collins, E. T., & Rand, D. G. (2020a). The implied truth effect: Attaching warnings to a subset of fake news headlines increases perceived accuracy of headlines without warnings. Management Science.

Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. (2020b). Understanding and reducing the spread of misinformation online. ACR North American Advances.

Pluviano, S., Watt, C., Ragazzini, G., & Della Sala, S. (2019). Parents’ beliefs in misinformation about vaccines are strengthened by pro-vaccine campaigns. Cognitive Processing, 20, 325–331.

Popken, B. (2018). Twitter deleted 200,000 Russian troll tweets. Read them here. NBC News, 14.

Poynter Institute (n.d.). The Code and the Platforms. International Fact-Checking Network. https://ifcncodeofprinciples.poynter.org/know-more/the-code-and-the-platforms.

Prestwich, A., Ayres, K., & Lawton, R. (2008). Crossing two types of implementation intentions with a protection motivation intervention for the reduction of saturated fat intake: A randomized trial. Social Science & Medicine, 67, 1550–1558.

Qiu, L. (2020). Hey @jack, Here Are More Questionable Tweets From @realdonaldtrump. The NewYork Times, June 3.

Roozenbeek, J., & Van Linden, D., S (2019). Fake news game confers psychological resistance against online misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5, 1–10.

Roozenbeek, J., Van Der Linden, S., & Nygren, T. (2020). Prebunking interventions based on inoculation theory can reduce susceptibility to misinformation across cultures. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1.

Roth, Y., & Pickles, N. (2020). Updating Our Approach to Misleading Information. Twitter [Online]. https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/product/2020/updating-our-approach-to-misleading-information [Accessed August 6 2022].

Schwarz, N., Sanna, L. J., Skurnik, I., & Yoon, C. (2007). Metacognitive experiences and the intricacies of setting people straight: Implications for debiasing and public information campaigns. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 127–161.

Shao, C., Ciampaglia, G. L., Varol, O., Yang, K. C., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2018). The spread of low-credibility content by social bots. Nature Communications, 9, 1–9.

Sheeran, P., & Orbell, S. (2000). Using implementation intentions to increase attendance for cervical cancer screening. Health Psychology, 19, 283.

Sheeran, P., Webb, T. L., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2006). Implementation intentions: Strategic automatization of goal striving. Self-regulation in Health Behavior, 121–145.

Shyh, T. H., Hin, H. S., & Ju, H. T. Y. (2023). Combat Fake News: An Overview of Youth’s Media and Information Literacy Education. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Creative Multimedia 2023, 786, 47. Springer Nature.

Sniehotta, F. F., Scholz, U., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). Bridging the intention–behaviour gap: Planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychology & Health, 20(2), 143–160.

Soetekouw, L., & Angelopoulos, S. (2022). Digital Resilience through Training protocols: Learning to identify fake News on Social Media. Information Systems Frontiers. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-021-10240-7.

Swire, B., & Ecker, U. K. (2018). Misinformation and its correction: Cognitive mechanisms and recommendations for mass communication. Misinformation and mass Audiences, 195–211.

Van Der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Rosenthal, S., & Maibach, E. (2017). Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Global Challenges, 1, 1600008.

Vargas, C. M., Burt, V. L., Gillum, R. F., Pamuk, E. R., & Survey, I. I. I. (1997). 1988–1991. Preventive Medicine, 26(5), 678–685.

Verplanken, B., & Faes, S. (1999). Good intentions, bad habits, and effects of forming implementation intentions on healthy eating. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 591–604.

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359, 1146–1151.

Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2003). Can implementation intentions help to overcome ego-depletion? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 279–286.

Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2007). How do implementation intentions promote goal attainment? A test of component processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 295–302.

Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2008). Mechanisms of implementation intention effects: The role of goal intentions, self-efficacy, and accessibility of plan components. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 373–395.

Weissberg, N. C. (1965). On DeFleur and Westie’s Attitude As a Scientific Concept. Social Forces, 422–425.

Wicker, A. W. (1969). Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. Journal of Social Issues, 25, 41–78.

Wong, S. L., Shields, M., Leatherdale, S., Malaison, E., & Hammond, D. (2012). Assessment of validity of self-reported smoking status. Health Reports, 23(1), D1.

Wood, T., & Porter, E. (2019). The elusive backfire effect: Mass attitudes’ steadfast factual adherence. Political Behavior, 41, 135–163.

Zimet, G. D., Rosberger, Z., Fisher, W. A., Perez, S., & Stupiansky, N. W. (2013). Beliefs, behaviors and HPV vaccine: Correcting the myths and the misinformation. Preventive Medicine, 57, 414–418.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no further acknowledgments for this research.

Funding

The authors received no external funding for this research.

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first and second author conceived of the research, theory, and hypotheses. The first author led the development of the manuscript, while the second author led the development of the experiment and the data analysis. The third author contributed to the revision process of the development of recommendations for social media platforms and users and the explanation of the mechanism behind implementation intentions in the context of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Armeen, I., Niswanger, R. & Tian, C.(. Combating Fake News Using Implementation Intentions. Inf Syst Front (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-024-10502-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-024-10502-0