Abstract

This study longitudinally investigates the socioeconomic differentials in South Korean adolescents’ occupational aspiration development while they approach the post-secondary transition. It also takes into account the two-fold relation between socioeconomic status and academic performance in shaping occupational aspirations: mediation and interaction. Using the Korean Education and Employment Panel (KEEP), the study documents two main results. First, there exists a significant socioeconomic gap in Korean adolescents’ occupational aspirations which is neither widened nor narrowed over the transition period. Second, the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic performance is not limited to mediation but demonstrates a significant interaction in developing occupational aspirations.

Résumé

Cette étude examine longitudinalement les différences socioéconomiques dans le développement des aspirations professionnelles des adolescents sud-coréens alors qu'ils approchent la transition post-secondaire. Elle prend également en compte la relation double entre le statut socioéconomique et la performance académique dans la formation des aspirations professionnelles : médiation et interaction. En utilisant le Panel coréen sur l'éducation et l'emploi (KEEP), l'étude documente deux principaux résultats. Premièrement, il existe un écart socioéconomique significatif dans les aspirations professionnelles des adolescents coréens qui n'est ni élargi ni réduit pendant la période de transition. Deuxièmement, la relation entre le statut socioéconomique et la performance académique n'est pas limitée à la médiation mais démontre une interaction significative dans le développement des aspirations professionnelles.

Resumen

Este estudio investiga longitudinalmente las diferencias socioeconómicas en el desarrollo de la aspiración ocupacional de los adolescentes surcoreanos mientras se acercan a la transición postsecundaria. También tiene en cuenta la relación doble entre el estatus socioeconómico y el rendimiento académico en la formación de las aspiraciones ocupacionales: mediación e interacción. Utilizando el Panel de Educación y Empleo de Corea (KEEP), el estudio documenta dos resultados principales. Primero, existe una brecha socioeconómica significativa en las aspiraciones ocupacionales de los adolescentes coreanos que ni se amplía ni se reduce durante el período de transición. Segundo, la relación entre el estatus socioeconómico y el rendimiento académico no se limita a la mediación sino que demuestra una interacción significativa en el desarrollo de las aspiraciones ocupacionales.

Zusammenfassung

Diese Studie untersucht longitudinal die sozioökonomischen Unterschiede in der Entwicklung der beruflichen Bestrebungen südkoreanischer Jugendlicher, während sie sich dem Übergang nach der Sekundarstufe nähern. Sie berücksichtigt auch die doppelte Beziehung zwischen sozioökonomischem Status und akademischer Leistung bei der Formung beruflicher Bestrebungen: Vermittlung und Interaktion. Unter Verwendung des Korean Education and Employment Panel (KEEP) dokumentiert die Studie zwei Hauptergebnisse. Erstens, es besteht eine signifikante sozioökonomische Kluft in den beruflichen Bestrebungen koreanischer Jugendlicher, die sich weder während der Übergangszeit vergrößert noch verkleinert. Zweitens, die Beziehung zwischen sozioökonomischem Status und akademischer Leistung beschränkt sich nicht auf Vermittlung, sondern zeigt eine signifikante Interaktion bei der Entwicklung beruflicher Bestrebungen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Aspiration is a human practice of forward-looking and exploring the future in the present time (Appadurai, 2004), and the gap between the aspiration and the present reality becomes the basis on which individuals assess the possibility of their desires and elicit strategic behaviours to realise them (Ray, 2006). Developing educational and occupational aspirations is therefore regarded as a crucial developmental task for adolescents as they support successful post-secondary and school-to-work transitions (Heckhausen et al., 2013). The existing literature indeed confirms that young people’s aspirations have long-term implications in attaining future employment status and labour market outcomes (e.g. Ashby & Schoon, 2010; Beal & Crockett, 2010; Cochran et al., 2011; Lee & Byun, 2019; Mau & Bikos, 2000; Schoon & Parsons, 2002).

It is also important to note that aspirations are not shaped in a vacuum but influenced by a myriad of contextual circumstances, particularly social origin (Gore et al., 2015; Hannah & Kahn, 1989; Kim & Yu, 2015; Lee & Rojewski, 2009; Marjoribanks, 2002; Shin & Kim, 2012). The positive relationships between socioeconomic backgrounds and aspirations, and indeed aspirations and future life outcomes, imply that adolescents’ aspirations may play a pivotal role in the intergenerational reproduction of inequalities. As such, it is essential to examine to what extent adolescents’ occupational aspirations are shaped by the social and opportunity structures to fully understand the role of adolescents’ aspirations as a potential component in addressing socioeconomic inequalities.

Despite the significance of adolescents’ aspirations, however, little is known about the long-term trends of socioeconomic disparity in occupational aspirations in South Korea, particularly during the period when adolescents approach the post-secondary transition. As such, this paper examines the socioeconomic gap in young people’s occupational aspirations while they approach the crucial transition period. It also focuses on the two-fold relation between socioeconomic status and academic performance in terms of shaping occupational aspirations, namely mediating and interacting mechanisms. In contrast to the well-established mediating role of academic performance, there remains an insufficiently explored interaction effect between socioeconomic status and academic performance. Using the Korean Education and Employment Panel (KEEP) survey, this paper addresses the following questions: (a) During the period when Korean adolescents approach the completion of secondary education, are there socioeconomic differentials in the development of their occupational aspirations? If so, how do the differentials change when adolescents approach the post-secondary transition? (b) In addition to the mediating role of academic performance linking socioeconomic status with occupational aspiration development, is there an interaction effect between socioeconomic status and academic performance?

The Korean educational system and post-secondary transition

The Korean educational system is characterised by its highly stratified nature and overheated educational aspiration called ‘education fever’. Although primary education and lower-secondary education are based on the common national curriculum, pupils in South Korea are divided into either academic or vocational high school tracks when they turn to upper-secondary education. Academic high schools are then divided into general academic schools, autonomous schools and special-purpose schools, the latter two of which are widely considered to have higher status than general schools in terms of academic superiority. As of 2021, 99.7% of those who completed lower-secondary education enrolled in upper-secondary schools, 73.9% of students in upper-secondary were in general academic high school, 10.7% were in either autonomous or special-purpose schools and 15.3% were in vocational high schools (KEDI, 2021). The stratification is further intensified at the higher education level, with the type of college, either 2-year or 4-year, and selectivity of institutions, resulting in intense competition among students for securing a place at a prestigious university.

The pressure upon Korean students is often exacerbated by ‘education fever’, which refers to an intensified social disposition, orientation, expectation and activity that highlights, reinforces and to an extent exaggerates the value and pursuit of higher academic attainment (Lee & Roger, 2008). Combined with the long-standing and exceptionally universal belief in meritocracy (Jeong, 2021; Park, 2021), the Korean education fever has been manifested in many forms, including excessive expenditure on shadow education and the globally highest level of education-related stress among students (Kim, 2015; Lee, 2005). Thus, the post-secondary transition is a crucial moment that determines not only the progression from dependent childhood to independent adulthood but the success of over 10-year educational investment. Given that students experience higher pressure and anxiety as they near the completion of secondary education and are therefore forced to adjust their occupational aspirations in accordance with their social and academic position, it is significant to examine how young people’s occupational aspirations change on the basis of their social origins over this key period. This paper seeks to fill this gap.

Relevant literature

Theoretical backgrounds

Despite the significance of aspiration and the wide employment of the term in research, a consistent definition of aspiration is rather elusive (Rojewski, 2005). Within the vast array of conceptualisations of aspiration, the most remarkable divergence arises in the distinction between ‘aspiration’ and ‘expectation’. The former indicates ideal aspiration not necessarily bounded by reality, while the latter represents aspiration tempered by the knowledge of obstacles and opportunities (Gottfredson, 1996; Rojewski, 2005). As succinctly articulated by Ashby and Schoon (2010), ‘whilst expectations describe what one thinks will happen, aspirations capture what one would like to happen’. On the other hand, it has long been acknowledged that even seemingly pure desires and ideals are not necessarily independent of social circumstances and living conditions (Bourdieu, 1977, 1984; Sen, 1995, 2001), making it difficult to establish a clear-cut distinction between the two concepts. Nonetheless, such distinction based on their relationship with social structures is illuminating for understanding aspiration as a social construct distinguished from mere interest or trait. In this study, therefore, occupational aspiration is conceptualised as ‘expressed goals toward ideal future jobs developed under the influence of social structures, which may not be consciously recognised’ in an attempt to differentiate it from occupational expectation and interest.

Among diverse theoretical attempts to explain the socioeconomic differentials in occupational aspiration development, we primarily draw upon two sociological approaches: the status attainment theory and Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus. The status attainment theory highlights how social origin influences occupational aspiration and subsequently future occupational attainment (Hotchkiss & Borow, 1996). More specifically, the Wisconsin model of status attainment suggests that the effects of socioeconomic background and cognitive ability on educational and occupational attainment are mediated by social psychological factors including the influence of significant others and status aspirations (Sewell et al., 1969, 1970; Woelfel & Haller, 1971), and such aspirations mediate most of the influence of explanatory variables on status attainment (Sewell et al., 2003). As for the development of occupational aspirations, this model also emphasises academic performance and significant others’ expectation as major paths through which parental socioeconomic status shape young people’s aspirations.

Contrary to the mechanistic model of status attainment theory, the notable work of Pierre Bourdieu around ‘habitus’ puts weights on an unconscious mechanism leading to socioeconomic disparities in occupational aspirations. That is, a person’s positionality within the social hierarchy dictated by their portfolio of capital is internalised and embodied as a subjective system of disposition called ‘habitus’ (Bourdieu, 1977, 1984). The habitus, or a ‘structured structure’ as Bourdieu put it, nestles down at one’s unconsciousness and makes them constantly estimate the objective probabilities of success of themselves and other people in the same class (Bourdieu, 1973, 1977). The very result of estimation then shapes what they desire for the future. To illustrate, those from upper-class families whose parents have university degrees and professional jobs develop a habitus which makes them consider attending university and securing a professional job as normal and probable. Those from disadvantaged backgrounds, by contrast, are likely to pursue a relatively moderate job even when they have higher academic achievements than their counterparts from advantaged backgrounds. Such a seemingly irrational decision is derived from their habitus, making them think of securing a professional job as ‘unthinkable’ or ‘not for the likes of us’ (Bourdieu, 1977).

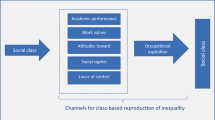

Aside from explaining the socioeconomic gradients in occupational aspirations, the two different approaches bring up an additional point of consideration: the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic performance in shaping occupational aspirations. The status attainment theory brings to the foreground the role of self-reflection upon educational achievement in developing occupational aspirations, suggesting that investigating the socioeconomic gap in adolescents’ occupational aspirations should be done with due consideration of the mediating role academic achievement might play. Meanwhile, Bourdieu’s approach focuses on how those from disadvantaged backgrounds unwittingly eliminate themselves from aspiring to prestigious careers owing to their social position and disposition. It provides a hint that the influence of academic achievement may not be equal if one’s system of disposition hinders them from aspiring to elite occupations. Thus, it should be instructive to see the potential interaction effect between socioeconomic status and academic performance in addition to the mediating effect via academic performance to grasp the full picture of socioeconomic gaps in adolescents’ occupational aspirations.

Socioeconomic status, academic performance and occupational aspirations

A vast body of empirical research has indeed shown the positive relationship between family backgrounds and adolescents’ occupational aspirations (Ashby & Schoon, 2010; Basler & Kriesi, 2019; Cochran et al., 2011; Expósito-Casas et al., 2022; Hannah & Kahn, 1989; Lee & Rojewski, 2009; Mau & Bikos, 2000). Sikora and Saha (2007), for instance, reveal a positive association between family backgrounds and occupational aspiration across different countries, using the 2000 and 2003 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey data. A similar positive association between family backgrounds and adolescents’ occupational aspirations has been found in South Korea (Cho & Ham, 2022; Ha et al., 2014; Lee & Byun, 2019; Lee et al., 2012; Shim & Seol, 2010; Shin & Kim, 2012; Yoo et al., 2013). Evidence on the significance and magnitude of family background effect on adolescents’ occupational aspiration is rather mixed, however (Howard et al., 2011). While Marini and Greenberger (1978) and Schoon and Parsons (2002) observe significant and large effects of family backgrounds on occupational aspirations, other empirical studies reported relatively small effect sizes (Berger et al., 2020; Gore et al., 2015; Howard et al., 2011; Marjoribanks, 2002). Some researchers even argue that family backgrounds do not have significant direct effects aside from their indirect effects mediated by other factors, e.g. parental aspiration, school type and academic performance (Kim & Yu, 2015; Yu & Shin, 2012). Such a discrepancy in the significance and magnitude of family background effect on adolescents’ occupational aspirations might derive from several reasons, and one possible explanation is that the time-based adjustability of occupational aspiration can cause the lack of perfect predictive validity, particularly within cross-sectional studies. Hence, longitudinal analysis of occupational aspiration is preferred to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between family backgrounds and occupational aspiration, which is one of the key contributions of this paper. Although a handful of Korean studies have analysed the over-time developmental patterns of adolescents’ occupational aspirations (e.g. Au, 2011; Ha et al., 2014; Kim, 2011; Lee & Rojewski, 2012; Oh & Choi, 2009), their observation windows do not cover the key period when Korean teenagers reach the completion of secondary education.

Another important determinant of occupational aspiration is academic performance. Since academic performance and intellectual ability have been discussed as one of the key factors mediating the effect of socioeconomic status on occupational aspiration development, many studies have empirically confirmed such a relationship in explicit – or implicit – ways (e.g. Ashby & Schoon, 2010; Cochran et al., 2011; Gore et al., 2015; Heckhausen & Tomasik, 2002; Marjoribanks, 2002; Nikel, 2023; Schoon & Parsons, 2002; Sikora & Saha, 2007; Watson et al., 2002). Likewise, the positive association between academic performance and youth aspirations is also consistently reported among Korean adolescents (Choi, 1990; Gong, 2011; Hwang et al., 2006; Kim & Yu, 2015; Kim, 2011; Park, 2011; Ryu & Jeong, 2017; Yoo et al., 2013). Among this line of studies, the findings of Yu and Shin (2012) are notable because they confirmed the role of academic performance as a mediator in the Korean context. Despite the abundance of empirical research which has confirmed the mediating role of academic performance, little is known about a possible interaction effect between socioeconomic status and academic performance in developing occupational aspirations. This paper, therefore, examines a longitudinal pattern of the socioeconomic gap in occupational aspiration development with due consideration of the two-fold relation between socioeconomic status and academic performance, particularly when adolescents go through the critical transition period.

Method

Data and participants

The data used here are from the Korean Education and Employment Panel (KEEP) survey provided by the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training (KRIVET). The KEEP is a longitudinal survey which comprises a nationally representative sample of Korean adolescents and examines the relationship between socio-demographic features, educational experience and subsequent labour market outcomes. In its first wave conducted in 2004, 2000 middle school seniors, 2000 academic high school seniors and 2000 vocational high school seniors were selected as a target sample through clustered-stratified sampling. The selected individuals were then followed up until 2015, with 12 waves of annual surveys. For this study, the 2000 middle school senior cohort data from the first to fourth waves were used. This 4-year analytic window represents the period during which students make their first educational tracking decisions and then approach the completion of upper-secondary education. In this period, they are expected to adjust their occupational aspirations to the most accessible ones based on their own abilities and opportunity structures in society (Gottfredson, 1996).

Given that the aim of this paper is to figure out adolescents’ occupational aspiration development, the sample was restricted to those who had provided information on their occupational aspirations at least once between the first and fourth waves. All individuals with missing values in the relevant variables were excluded from the analysis, resulting in a restricted sample of 1348 participants. Additional statistical analyses were conducted using logistic regression models to check if there exist any potential bias that arises from the sample restriction, and the results implied that being included in the sample does not depend on outcome variables but on gender and the type of high school attended. To illustrate, the restricted sample is more female and has a higher proportion of students who attended academic high schools than the target sample. Despite this, there exists a body of research arguing that complete case analysis also gives unbiased results as long as the chance of being a complete case does not depend on the outcome variable(s) after controlling for the covariates in the main model (Carpenter & Kenward, 2013; Hughes et al., 2019; Little & Rubin, 2002). Given that being included in the final sample is not associated with the outcome values and that maximum likelihood estimation is relatively robust against missingness, we claim that the restricted sample could provide results with a minimised bias without more sophisticated strategies to deal with missing data.

Measures

Occupational aspiration (occuaspSEI)

The participants were asked at every annual survey to answer the question, ‘If you have decided on the job you want to have in the future, what is it?’ The responses of the participants were transcribed into 3-digit or 4-digit codes of the Korean Employment Classification of Occupations (KECO) system, which classifies 450 distinctive job units into 10 major groups, 35 sub-major groups and 136 minor groups. We matched these KECO classifications with the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08) to recode them again into the International Socioeconomic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI) (Ganzeboom, 2010). If a KECO code had more than one corresponding ISCO-08 code, the average ISEI score of the corresponding ISCO-08 codes was used.

It has long been criticised that many empirical studies have operationalised aspiration and expectation with identical survey questions (Morgan, 2007; Rojewski, 2005). In light of this, the questionnaire used in this study for measuring occupational aspiration might not be ideal for distinguishing it from occupational expectation. However, given that the survey question elicits optimistic future plans, and that the questionnaire asks the likelihood of getting the reported job separately in the following question, the question seems to be qualifying for the analytic purposes of this study.

Socioeconomic status (poccuSEI)

The variable for individuals’ socioeconomic status captures the participants’ family backgrounds in terms of their parental socioeconomic position. This variable was measured by parental occupations recorded with the KECO scheme, matched with the ISCO-08 and then converted into a continuous form of ISEI employing the same approach as the occupational aspiration variable. Because the proportion of missing values in maternal occupation is 42.05%, we aggregated paternal and maternal occupations by selecting the higher ISEI score of the two to minimise the number of cases with missing values.

Time (WAVE)

The first to fourth wave data were marked from 0 to 3 in sequence to indicate which time point each observation is from. We assigned the first wave to zero so that the intercept of the model can be interpreted as the value for the initial point.

Academic performance (tassess)

Academic performance assessed by homeroom teachers at the first wave was included as a proxy for the participants’ academic ability. When the first wave of the survey was conducted, teachers were required to respond to the question asking the ranking percentage of the participants’ academic performance. Since the ranking percentages were reported in inverse order (e.g. top-performing students are close to 0, while worst-performing students are near 100), we reversed it for the convenience of interpretation.

Gender (female)

The participants’ genders at the first wave were recoded into a dummy variable with 0 = male and 1 = female.

Parental aspiration (poccuaspSEI)

In the first wave of the household survey in 2004, respondents were asked to report what kind of job they want their child to have when the child becomes 35 years old. The responses were recoded into KECO codes and then matched with both ISCO-08 and ISEI as occupational aspirations were processed, resulting in a continuous variable that represents vertical levels of parental occupational aspiration.

School type (academic)

Types of high school the participants attended between the second wave and the fourth wave were coded as a binary variable, i.e. vocational school (value 0) or academic school (value 1). If the data for school type were missing in the second wave but reported in the third or fourth year, it was imputed from the later wave datasets. Table 1 illustrates the descriptive statistics of all variables.

Analytical approach

Analyses are based on linear multilevel models with repeated measures to examine not only the formation of occupational aspiration but also the growth trajectories over a 4-year period of time (Hox et al., 2010; Peugh, 2010; Singer & Willett, 2003; West et al., 2014). Multilevel analyses include both fixed and random effects; the former represents the relationship of the covariates to the dependent variable, e.g. occupational aspiration, for an entire population while the latter is specific to clusters or participants within the population. Examining both fixed and random effects in a longitudinal study, therefore, enables us to answer the research questions regarding the trajectory of occupational aspirations of the population as well as individual differences across participants in their trajectories (Lu & Sacker, 2020).

We analysed the data with the Stata MP (version 17) and applied a multilevel mixed-effect linear regression with the ‘mixed’ command. Since the sample size is sufficiently large with the number of 1348 at level 2, the full maximum likelihood was used to fit the model (Peugh, 2010; Singer & Willett, 2003). Given that failing to take into account autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity in multilevel modelling can lead to incorrect estimation of standard errors and inferential conclusions (Bliese & Ployhart, 2002), we built competing models which do or do not allow for an autoregressive structure in the error covariance to determine the presence of autocorrelation. The detailed processes of model selections are provided in the following section.

Results

Model selection

We initially calculated a random intercept model (model 0Footnote 1) to confirm whether there is systematic variation in the outcome that is worth exploring and, if so, where that variation resides – within or between people. Since the intra-class correlation coefficient of the null model showed that 50.62% of the variation in occupational aspiration occurred between participants, a multilevel model seemed to be appropriate for analysing the dataset (Peugh, 2010).

Then, we introduced a level-1 predictor, WAVE, indicating the time point when each occupational aspiration observation was collected to determine the fixed function of time (model 1). Given that the linear growth term was statistically significant with the parameter estimate of −1.17 (\(z = - 9.04\), \(p < 0.001\)), occupational aspirations of the participants, on average, linearly declined over the given period. The relationship between occupational aspiration and time was further reviewed by including the square of WAVE (WAVE2) to check if it shows a quadratic relationship; but the quadratic time effect (WAVE2) was excluded from the model owing to its statistically nonsignificant effect (\(z = 0.94\), \(p = 0.349\)). As such, further model building was carried out with the assumption that occupational aspirations decline in a linear fashion.

In the next step, we examined both the variability in the slope parameter and the presence of autocorrelation in outcomes, i.e. occupational aspirations. In a bid to select the best-fit model for the level-1 growth model, three different competing models were contrasted, namely a random slope model with an independent residual structure (model 2A), a random slope model with a first-order autoregressive residual structure (model 2B) and a random intercept model with a first-order autoregressive residual structure (model 2C). We compared the goodness of model fit using the likelihood ratio tests (LRT) and information criterion scores, i.e. Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) scores. Whilst the three sub-models (models 2A, 2B and 2C) showed improved model fits compared with model 1, the AIC and BIC scores offered conflicting results between models 2B and 2C with a lower AIC score for model 2B and a lower BIC score for model 2C. The difference in the AIC scores between models 2B and 2C was, however, only 1.01, which is inconclusive to support that there is a significant model improvement (Singer & Willett, 2003). The result of LRT between models 2B and 2C further suggested that there is no statistical difference between the two sub-models at the significance level of 0.05 (\(\chi^{2} \left( 1 \right) = 3.01\), \(p = 0.0827\)). Given the non-significant LRT statistics, the lower BIC scores and the marginal difference in the AIC scores, the random intercept model with an autoregressive error structure (model 2C) was selected for further model buildings. It indicates that it is safe to assume that the growth for all participants follows the same rate of decline without significant participant-specific variations.

After the level-1 growth structure was confirmed, level-2 predictors were sequentially added to the model. We first added the key predictor, family background (SES) (see model 3A in Table 2), and then included academic performance (see model 3B in Table 2) to see the changes in the regression coefficient for the key predictor, i.e. SES. If the coefficient of SES decreases when academic performance is added to the model, it means academic performance mediates the effect of SES on occupational aspirations. In model 3C (full model), other control variables and the interaction term between SES and academic performance were included to check whether the effect of academic performance on occupational aspirations varies by individuals’ socioeconomic status. This resulted in the following equations for our full model:

where the subscript \(i\) refers to repeated response observations (level 1 unit) collected from a participant \(j\) (level 2 unit) over time.

The socioeconomic gap in adolescents’ occupational aspirations

The random-intercept growth model (see model 3A in Table 2) shows that individuals’ family backgrounds (SES) have a statistically significant and positive impact on adolescents’ occupational aspirations as has been found in many studies in South Korea (e.g. Ha et al., 2014; Lee & Byun, 2019; Yoo et al., 2013). To illustrate, a one-unit increase in individuals’ SES index is, on average, associated with a 0.149 unit increase in their occupational aspirations index, regardless of when they were measured during the 4-year period. Given that the aspiration index entails hierarchy in terms of socioeconomic level, by definition, those with higher SES, on average, have higher occupational aspirations.

With regard to the average growth trajectory of Korean adolescents’ occupational aspirations, the fixed intercept represents the average value of occupational aspirations at the initial point (wave 0), which is 50.619 (see model 3A in Table 2). Since then, the average Korean adolescents’ occupational aspirations linearly declined with a rate of change of −1.171 after controlling for SES (see model 3A in Table 2). To put it differently, a 1-year elapse of time is, on average, associated with a 1.171 unit decrease in adolescents’ occupational aspirations. It is worth noting that there exists no significant variability across individuals in the rate of occupational aspiration change over time. The systematic comparisons of model fit in the previous section revealed that the model without a random slope explains better the given sample than the model with a random slope. That is, individuals, on average, show a downward trend in their occupational aspirations during the given 4-year period with the same rate of change regardless of their individual features including their socioeconomic status.

The two-fold relation between socioeconomic status and academic performance

To test the mediating effect of academic performance, the independent variable of academic performance was added to model 3A, leading to model 3B. The result of model 3B in Table 2 describes that the coefficient of socioeconomic status decreases from 0.149 to 0.096 and remains statistically significant. This result represents that the effect of socioeconomic status on occupational aspiration is partially mediated by academic performance. Then, the interaction term between academic performance and family background was included in model 3C to examine whether the effect of academic performance on occupational aspirations is comparable across individuals from different socioeconomic backgrounds (Table 2). In this model, other control variables including gender, parental aspirations and school type are also taken into account. In model 3C, the interaction term between SES and academic performance shows a statistically significant correlation with adolescents’ occupational aspirations, albeit with a small effect size. The result demonstrates that, on average, having better academic achievement is positively associated with occupational aspirations; however, such a positive effect of academic performance on adolescents’ occupational aspirations is conditional on family socioeconomic backgrounds. To put it differently, those from higher SES backgrounds benefit more from higher academic performance than those from lower SES backgrounds.

To further provide a meaningful description of the effects of the independent variables, e.g. academic performance and family backgrounds, the marginal effect of academic performance on occupational aspiration was also computed, holding the value of family backgrounds (SES) constant at five different values (Table 3). There indeed appears to be a significant impact of academic performance on occupational aspiration for all values of family background (SES) although the magnitude varies across SES. For those whose SES is low (−1 SD from the mean) for example, a one-unit increase in academic performance is associated with a 0.082 unit increase in occupational aspiration on average, while those from high SES backgrounds (+1 SD from the mean) show a 0.123 unit increase in occupational aspiration, on average, with the same amount of increase in academic performance.

Figure 1 illustrates that the effect of academic performance increases as the SES value increases. This result implies that academic performance as a predictor of occupational aspiration exerts a stronger influence on adolescents from more advantaged family backgrounds than it does on those from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Given that academic performance has, on average, a positive association with occupational aspiration, it suggests that the boosting effect of academic performance on occupational aspiration is significantly weaker for disadvantaged adolescents compared with their more advantaged peers.

Discussion

This paper has investigated the impact of family socioeconomic backgrounds on the development of occupational aspirations for a cohort of young people in South Korea. We have contributed to this field in two important respects. First, we have zoomed in on the 4-year period when adolescents make crucial educational and occupational decisions nearing the post-secondary transition by utilising a longitudinal analysis. As a result, we have found that there exists a significant socioeconomic gap in Korean adolescents’ occupational aspirations with a declining pattern of occupational aspirations over the given period in general. Although including control variables in the model reduced the impacts of SES on adolescents’ occupational aspirations, SES still showed a statistically significant effect on occupational aspiration. This result adds to the previous findings by confirming the presence of a socioeconomic gap on the verge of the post-secondary transition. It is also important to note that, despite echoing the findings from the existing literature exploring the young people’s developmental trajectories of occupational aspiration in South Korea, i.e. its declining pattern, this study could not find any empirical evidence that the occupational aspirations of the participants decline at different paces depending on their socioeconomic backgrounds or other demographic features. Given the significant fixed effect of socioeconomic status on occupational aspirations, however, the same rate of decline over the period means that the socioeconomic inequality is not reduced and rather persists until young people encounter the crucial transition to higher education or labour market.

Some existing literature has indeed found that occupational aspirations of those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds diminish more slowly than those of their more disadvantaged counterparts (e.g. Ha et al., 2014), while others attribute the variability in the rate of change to academic performance, gender and school types (Ha et al., 2014; Kim, 2011; Lee & Rojewski, 2012; Oh & Choi, 2009). The discrepancy in the result regarding the slope variance of occupational aspiration development possibly arises from differences in observation periods and research designs. The existing literature observes different age groups, focusing rarely on the post-secondary transition. Since the transitional period this study has investigated is characterised by intense competition for higher education and the labour market, the buffering effect of high socioeconomic status found in the previous studies might diminish to insignificant levels. Furthermore, allowing for autocorrelation within the dependent variable in this study may have caused the conflicting result considering that other studies did not account for the presence of autocorrelation.

Second, we have also paid particular attention to the two-fold relation between socioeconomic status and academic performance in shaping occupational aspirations by simultaneously examining the mediating relation and the interaction effect. As suggested by the existing literature, our study has reconfirmed that academic performance in part mediates the effect of socioeconomic status on occupational aspirations. However, the mediating role of academic performance which links socioeconomic status and occupational aspirations is, on average, weakened when including the interaction term between socioeconomic status and academic performance. Instead, we have identified a statistically significant interaction effect between family background and academic performance, which has been scarcely detected to date. It implies that, although academic performance and occupational aspiration have a positive association, the boosting effect of academic performance is relatively restricted for adolescents from lower socioeconomic backgrounds compared with those from more advantaged backgrounds. The presence of an interaction effect between family background and academic performance is noteworthy since the impact of family background on occupational aspiration is not limited to its direct and indirect effects but exerts some additional influences at the same time by swaying the magnitude of academic performance effect on occupational aspiration.

Conclusion and implications

The above findings from this study suggest that active educational interventions are required in South Korea to raise occupational aspirations among students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Particularly, the identified interaction between socioeconomic status and academic performance implies that narrowing the educational achievement disparity may not be enough to address the inequality in aspiration and consequently future educational and status attainment gap. Traditionally rooted in the trait-and-factor theory emphasising proper matching between personal traits and job factors (Lee & Jyung, 2004; Parsons, 1909), career education in South Korea often risks reducing the low occupational aspirations of deprived adolescents to personal matters of interests, values, and aptitudes. Although the National School Career Education Goals and Performance Criteria (Ministry of Education, 2015) were established in 2015 to deconstruct biases about jobs and resolve career barriers, they are still criticised for paying little attention to the fact that career barriers can substantially vary across students from different family backgrounds (Jung, 2018). It is high time to increase awareness among policymakers and career and educational practitioners that socioeconomic status is an important constraint for career development and help young people develop their own occupational aspirations and reach their potential without socioeconomic barriers. Further, this attempt should be combined with the effort to provide them with sufficient opportunities and assistance to realise their own aspirations.

In addition, given that the socioeconomic gap in occupational aspirations persist while students go through the crucial transition, such interventions are more likely to be successful when they are applied earlier than when students reach the last year of lower-secondary education. In this period, students should make an important educational decision on the type of upper secondary schools they attend, which in turn has long-term implications for their occupational aspiration development and future outcomes. Thus, it would be ideal if the career development guidance and assistance for raising occupational aspirations among disadvantaged students are concentrated before mid-teenage when they are more open to diverse possibilities.

Despite several strengths and contributions, this study is not without limitations. Although occupational status is often regarded as the single best indicator of individual socioeconomic standings, it may still have limitations in explaining the variability within occupations and information on unemployed individuals. Further, the results do not necessarily imply a definite causal relationship between socioeconomic status and occupational aspiration. Even though the study identified a socioeconomic gap in adolescent occupational aspiration, the influence of family backgrounds on aspiration may still be overestimated mainly due to confounding factors that were not included in the models. To clarify the causality, future research can usefully consider including additional theoretically relevant factors and employing more sophisticated research designs, e.g. quasi-experimental design, if data availability allows.

Notes

The equations for models 0, 1 and 2 are omitted for simplicity. Those equations are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition: A cross-disciplinary dialogue on development policy. World Bank Publications.

Ashby, J. S., & Schoon, I. (2010). Career success: The role of teenage career aspirations, ambition value and gender in predicting adult social status and earnings. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 350–360.

Au, Y. (2011). The study of adolescents and their parents’ changes on job aspiration. The Journal of Career Education Research, 24(4), 21–39.

Basler, A., & Kriesi, I. (2019). Adolescents’ development of occupational aspirations in a tracked and vocation-oriented educational system. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115, 103330.

Beal, S. J., & Crockett, L. J. (2010). Adolescents’ occupational and educational aspirations and expectations: Links to high school activities and adult educational attainment. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 258–265.

Berger, N., Holmes, K., Gore, J. M., & Archer, J. (2020). Charting career aspirations: A latent class mixture model of aspiration trajectories in childhood and adolescence. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47(4), 651–678.

Bliese, P. D., & Ployhart, R. E. (2002). Growth modeling using random coefficient models: Model building, testing, and illustrations. Organizational Research Methods, 5(4), 362–387.

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In R. Brown (Ed.), Knowledge, education, and cultural change (pp. 71–112). Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of Taste (R. Nice, Trans.). Routledge.

Carpenter, J. R., & Kenward, M. G. (2013). Multiple imputation and its application. Wiley.

Cho, Y., & Ham, S. H. (2022). Does career guidance narrow the aspiration gap? Socioeconomic status and occupational aspirations of school children. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 19(1), 45–66.

Choi, Y.-J. (1990). A study on the causal model of occupational aspirations of high school students in rural areas. The Journal of Vocational Education Research, 9(1), 115–130.

Cochran, D. B., Wang, E. W., Stevenson, S. J., Johnson, L. E., & Crews, C. (2011). Adolescent occupational aspirations: Test of Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription and compromise. The Career Development Quarterly, 59(5), 412–427.

Expósito-Casas, E., González-Benito, A., & López-Martín, E. (2022). Data mining to detect variables associated with the occupational aspirations of Spanish 15-year-old students. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09554-y

Ganzeboom, H. B. G. (2010). International Standard Classification of Occupations: ISCO-08 with ISEI-08 Scores. http://www.harryganzeboom.nl/

Gong, Y. J. (2011). The development of youth’s occupational aspirations: The role of academic performance, academic self-efficacy, and sex-roles in predicting occupational aspirations. The Korea Journal of Youth Counseling, 19(1), 127–141.

Gore, J., Holmes, K., Smith, M., Southgate, E., & Albright, J. (2015). Socioeconomic status and the career aspirations of Australian school students: Testing enduring assumptions. The Australian Educational Researcher, 42, 155–177.

Gottfredson, L. S. (1996). Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription and compromise. In: D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development (3rd ed., pp. 179–232). Jossey-Bass.

Ha, M.-S., Kim, J.-H., & Kim, B.-H. (2014). Longitudinal changes of late adolescents’ job aspiration and the effect of individual and environmental variables. Korea Journal of Counseling, 15(4), 1495–1513.

Hannah, J.-A.S., & Kahn, S. E. (1989). The relationship of socioeconomic status and gender to the occupational choices of grade 12 students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 34(2), 161–178.

Heckhausen, J., Chang, E. S., Greenberger, E., & Chen, C. (2013). Striving for educational and career goals during the transition after high school: What is beneficial? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(9), 1385–1398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9812-5

Heckhausen, J., & Tomasik, M. J. (2002). Get an apprenticeship before school is out: How German adolescents adjust vocational aspirations when getting close to a developmental deadline. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(2), 199–219.

Hotchkiss, L., & Borow, H. (1996). Sociological perspective on work and career development. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development: Applying contemporary theories to practice (3rd ed., pp. 281–334). Jossey-Bass.

Howard, K. A. S., Carlstrom, A. H., Katz, A. D., Chew, A. Y., Ray, G. C., Laine, L., & Caulum, D. (2011). Career aspirations of youth: Untangling race/ethnicity, SES, and gender. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 98–109.

Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & van de Schoot, R. (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis Group.

Hughes, R. A., Heron, J., Sterne, J. A. C., & Tilling, K. (2019). Accounting for missing data in statistical analyses: Multiple imputation is not always the answer. International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(4), 1294–1304.

Hwang, M.-H., Kim, J.-H., Ryu, J. Y., & Heppner, M. J. (2006). The circumscription process of career aspirations in South Korean adolescents. Asia Pacific Education Review, 7(2), 133–143.

Jeong, T. (2021). Meritocracy and the dilemma of fairness: Competing criteria for value judgment. Economy and Society, 12–46.

Jung, A.-K. (2018). Review and critique of the Korean National School Career Education Goals and Performance Criterion. Journal of Education and Culture, 24(5), 677–698.

KEDI. (2021). Statistical Yearbook of Education 2021 Pre-primary, Primary and Secondary Education Survey. Korean Educational Development Institute. https://kess.kedi.re.kr/publ/view?searchYear=2021&survSeq=2021&publSeq=2&menuSeq=3894&itemCode=02

Kim, J., & Yu, B. (2015). The effects of parents’ socio-economic status on the levels of children’s occupational aspiration: Focusing on the mediation process and interaction effects. Korean Journal of Sociology of Education, 25(2), 23–46.

Kim, K. N. (2011). A longitudinal study into the effects of different high school on students’ occupational aspirations. Korean Journal of Educational Research, 49(4), 121–145.

Kim, M. (2015). The subjective well-being of Korean children and its policy implications. Health and Welfare Policy Forum, 220, 14–26.

Lee, B., & Byun, S. (2019). Socioeconomic status, vocational aspirations, school tracks, and occupational attainment in South Korea. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 1494–1505.

Lee, C. (2005). Korean education fever and private tutoring. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 2(1), 99–107.

Lee, I. H., & Rojewski, J. W. (2009). Development of occupational aspiration prestige: A piecewise latent growth model of selected influences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(1), 82–90.

Lee, I. H., & Rojewski, J. W. (2012). Development of occupational aspirations in early Korean adolescents: A multiple-group latent curve model analysis. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 12(3), 189–210.

Lee, J. B., Choi, D. S., & Oh, C. H. (2012). Determinants of occupational aspirations level of high school students. Journal of Agricultural Education and Human Resource Development, 44(4), 25–43.

Lee, S., & Roger, C. S. (2008). Is education fever treatable? Case studies of first-year Korean students in an American university. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 5(2), 113–132.

Lee, S. S., & Jyung, C. Y. (2004). A study on the zone of acceptable alternatives and occupational aspiration of high school students based on Gottfredson’s theory. Journal of Agricultural Education and Human Resource Development, 36(3), 43–58.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Lu, W., & Sacker, A. (2020). A case study of the application of a multilevel growth curve model and the prediction of health trajectories. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Marini, M. M., & Greenberger, E. (1978). Sex differences in occupational aspirations and expectations. Sociology of Work and Occupations, 5(2), 147–178.

Marjoribanks, K. (2002). Family contexts, individual characteristics, proximal settings, and adolescents’ aspirations. Psychological Reports, 91(3), 769–779.

Mau, W.-C., & Bikos, L. H. (2000). Educational and vocational aspirations of minority and female students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling and Development, 78(2), 186.

Ministry of Education. (2015). National school career education goals and performance criterion. Ministry of Education.

Morgan, S. L. (2007). Expectations and aspirations. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology. Wiley.

Nikel, Ł. (2023). Exploring occupational aspirations of school-age children by fluid intelligence, gender and grade. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 23(1), 1–18.

Oh, H., & Choi, Y. (2009). The impact of individuals’ socioeconomic status and academic achievements on occupational aspirations. In The 3rd KELS (Korean Education Longitudinal Study) Conference (pp. 299–318).

Park, K. (2021). Perception and characteristics of meritocracy in Korea. Citizen and the World, 1–39.

Park, Y. (2011). Relationship of academic achievement, self-esteem, parental educational level and occupational aspiration in elementary school students. The Korean Journal of Elementary Counseling, 10(1), 95–108.

Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Houghton Mifflin.

Peugh, J. L. (2010). A practical guide to multilevel modeling. Journal of School Psychology, 48(1), 85–112.

Ray, D. (2006). Aspirations, poverty, and economic change. Oxford University Press.

Rojewski, J. W. (2005). Occupational aspirations: constructs, meanings, and application. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 131–154). Wiley.

Ryu, J., & Jeong, J. (2017). A meta-analysis on the variables related to adolescents’ occupational aspiration levels. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 20(1), 27–56.

Schoon, I., & Parsons, S. (2002). Teenage aspirations for future careers and occupational outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60, 262–288.

Sen, A. (1995). Inequality reexamined. Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2001). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

Sewell, W. H., Haller, A. O., & Ohlendorf, G. W. (1970). The educational and early occupational status attainment process: Replication and revision. American Sociological Review, 35(6), 1014–1027.

Sewell, W. H., Haller, A. O., & Portes, A. (1969). The educational and early occupational attainment process. American Sociological Review, 34(1), 82–92.

Sewell, W. H., Hauser, R. M., Springer, K. W., & Hauser, T. S. (2003). As we age: A review of the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, 1957–2001. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 20, 3–111.

Shim, K.-S., & Seol, D.-H. (2010). Occupational aspirations of college students in South Korea: The effect of social capital and cultural capital. Korea Journal of Population Studies, 33(2), 33–59.

Shin, S., & Kim, K. (2012). The effects of family background on occupational aspiration: With special reference to the effects of social capital within family. The Korea Educational Review, 18(1), 121–141.

Sikora, J., & Saha, L. J. (2007). Corrosive inequality? Structural determinants of educational and occupational expectations in comparative perspective. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 8(3), Article 3.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press.

Watson, C. M., Quatman, T., & Edler, E. (2002). Career aspirations of adolescent girls: Effects of achievement level, grade, and single-sex school environment. Sex Roles, 46(9/10), 323–335.

West, B. T., Welch, K. B., & Galecki, A. T. (2014). Linear mixed models: A practical guide using statistical software (2nd ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Woelfel, J., & Haller, A. O. (1971). Significant others, the self-reflexive act and the attitude formation process. American Sociological Review, 36(1), 74–87.

Yoo, H. J., Kim, K. H., Shin, I. C., & Oh, B. (2013). Youth occupational aspiration and mismatch between desired occupation and college major choice in Korea. The Journal of Vocational Education Research, 32(6), 91–110.

Yu, B., & Shin, S. (2012). The effects of parents-children communication styles according to family background on teacher-students relationships and occupational aspirations. Studies on Korean Youth, 23(4), 51–77.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yong, A., Lee, S. The socioeconomic gap in the development of Korean adolescents’ occupational aspirations while approaching the post-secondary transition. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-024-09690-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-024-09690-7