Abstract

The present study explored the occupational aspirations of school-age children (N = 394) comparing differences by gender, level of intelligence and grade level. Results indicated that girls’ aspirations were more realistic, intrinsically motivated, prosocial and inclusive of higher education than those of boys. Moreover, a higher level of intelligence only from the fourth grade and 10 years of age was associated with higher education aspirations. These results suggest that in choosing occupational aspirations, children from the fourth grade (aged 10–11) may begin to be guided by intellectual abilities. The contribution of these results to career development theories is discussed.

Résumé

Exploration des aspirations professionnelles des enfants d'âge scolaire selon l'intelligence fluide, le sexe et le niveau scolaire La présente étude a exploré les aspirations professionnelles des enfants d'âge scolaire (N = 394) en comparant les différences selon le sexe, le niveau d'intelligence et le niveau scolaire. Les résultats indiquent que les aspirations des filles sont plus réalistes, intrinsèquement motivées, prosociales et incluent davantage l'enseignement supérieur que celles des garçons. De plus, un niveau d'intelligence plus élevé, seulement à partir de la quatrième année et de l'âge de 10 ans, était associé à des aspirations d'études supérieures. Ces résultats suggèrent que, dans le choix des aspirations professionnelles, les enfants à partir de la quatrième année (10-11 ans) peuvent commencer à être guidés par les capacités intellectuelles. La contribution de ces résultats aux théories du développement de carrière est discutée.

Zusammenfassung

Erforschung der Berufswünsche von Kindern im Schulalter nach fluider Intelligenz, Geschlecht und Klassenstufe In der vorliegenden Studie wurden die Berufswünsche von Kindern im Schulalter (N = 394) untersucht, wobei Unterschiede nach Geschlecht, Intelligenz und Klassenstufe verglichen wurden. Die Ergebnisse zeigten, dass die Berufswünsche von Mädchen realistischer, intrinsisch motivierter, prosozialer und auf eine höhere Bildung ausgerichtet waren als die von Jungen. Außerdem ging ein höheres Intelligenzniveau erst ab der vierten Klasse und im Alter von 10 Jahren mit höheren Bildungswünschen einher. Diese Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass sich Kinder ab der vierten Klasse (im Alter von 10-11 Jahren) bei der Wahl ihres Berufswunsches möglicherweise von ihren intellektuellen Fähigkeiten leiten lassen. Der Beitrag dieser Ergebnisse zu Theorien über die berufliche Entwicklung wird diskutiert.

Resumen

Explorando las aspiraciones ocupacionales de escolares por inteligencia fluida, género y grado Este studio explore las aspiraciones ocupacionales de escolares (N=394) comparando las diferencias de género, nivel de inteligencia y grado. Los resultados indicaron que las aspiraciones de las niñas eran mas realistas, intrínsecamente motivadas, prosociales e inclusivas en educación superior en coparación con las de los niños. Además, un mayor nivel de inteligencia a partir del cuarto grado y los 10 años de edad se asoció con las aspiraciones a la educación superior. Estos resultados sugieren que al escoger las aspiraciones vocacionales, el alumnado a partir de cuarto grado (10 - 11 años de edad) podrían empezar a ser guiados por las habilidades intelectuales. Se discute también la contribución de estos resultados a las teorias de desarrollo de la Carrera.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Aspirations reflect a desire to achieve a goal or accomplish ambitious plans. They can refer to goals oriented in the present or in the future (Carroll et al., 2009; Moulton et al., 2018). Aspirations are associated with important areas of an individual's daily activities. In particular, aspirations can play an important role in the educational and school area. In this area of interest, scientific researchers mainly focus on studying the educational and occupational aspirations of children and the aspirations of parents for their children (Helwig, 2008; Moulton et al., 2018). Educational aspirations refer to the goals that students set for learning outcomes, the educational stage or other school achievements (Carroll et al., 2009; Fraser & Garg, 2014; Lv et al., 2018; Trebbels, 2015), whilst occupational aspirations reflect the work that children would like to pursue in the future (Flouri et al., 2015; Moulton et al., 2018). Both educational and occupational aspirations are related to the important skills of children that allow them to perform school activities (Ansong et al., 2019; Lv et al., 2018; Metsäpelto et al., 2017). Therefore, it is reasonable to know and understand the nature of aspirations. Research to date has focussed on the relationship between aspirations and, for instance, self-efficacy (Bandura et al., 2001), resilience (Sanders et al., 2017), school achievement (Metsäpelto et al., 2017) and parents' aspirations for their children (Lee & Byun, 2019; Sheldrake, 2020). As a result, it is known that aspirations depend on individual differences and the social context (Moulton et al., 2018).

The current study focussed on broaden the existing knowledge about the occupational aspirations of school-age children. It is known that occupational aspirations depend on the child's developmental stage. However, the breakthrough moments in the development of children's occupational aspirations and the factors on which they depend are not entirely clear (Gottfredson, 1981; Helwig, 2008). The aim of this study was to explore the occupational aspirations of school-age children using the level of fluid intelligence, grade and gender. This will allow an answer to the research questions of whether the occupational aspirations of school-age children depend on individual resources, in particular intellectual and how gender and grade relate to children’s occupational aspirations.

Occupational aspirations in children

In the area of aspiration research, two approaches can be found—one identifying aspirations with expectations and the other separating these two phenomena. Researchers who separate aspirations from expectations associate aspirations with an ideal goal and hope, and expectations with a realistic goal and belief that this goal will be achieved (Flouri et al., 2015; Gorard et al., 2012). Children's occupational aspirations can be examined by asking them questions about what occupation they would like to do in the future, whilst expectations can be examined by asking what occupation they think they will do in the future (Flouri et al., 2015; Goldenberg et al., 2001).

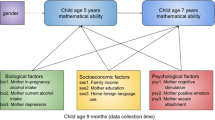

Children's occupational aspirations depend on individual differences and the social context (Hughes, 2016; Sheldrake, 2020). Amongst the various social factors, such as ethnicity, parents’ education and parents’ attitudes (Carroll et al., 2009; Hughes, 2016; Kewalramani & Phillipson, 2020), the socioeconomic status of the family plays a very important role (Flouri et al., 2015). Individual differences related to occupational aspirations include affective, cognitive and behavioural dispositions (Hughes, 2016; Sheldrake, 2020). Bandura et al. (2001) revealed that children's self-efficiency is related to children's occupational aspirations. Children who are convinced of their abilities in some school area aspire to occupations that require similar skills. Self-confidence, self-esteem, school motivation play important role in children careers aspirations (Sheldrake, 2020). Children with science-oriented aspirations are characterized by higher mathematics self-confidence, science self-confidence, school motivation and self-esteem. Pulkkinen (2001) noticed that lower career orientation can be associated with aggressive behaviour in boys and anxiety, submissiveness in girls. Another probably important individual differences related to occupational aspirations is intelligence. To date, it is not clear how intellectual capability is associated to children's occupational aspiration.

Occupational aspirations and fluid intelligence

Amongst theories of intelligence, most of them come from the hierarchical model proposed by Spearman (1927). According to Spearman (1927), intelligence consists of the g factor (general intelligence), common to all intelligence tests, and an indefinite number of s (specific) factors that measure specific abilities. Cattell (1971) in the factor g distinguished fluid (gf) and crystallized (gc) intelligence. Fluid intelligence represents problem-solving, inductive and deductive reasoning. Crystallized intelligence represents extracting, structuring and organizing knowledge. Some study indicate that fluid intelligence is equivalent to general intelligence (Kvist & Gustafsson, 2008). Both general and fluid intelligence are related to reasoning processes.

Summing up various scientific research results, it can be pointed out that intelligence is an important predictor of school achievement (Rudasill et al., 2014; Stańczak, 2013). In turn, children's school achievements are related to their aspirations (Basler & Kriesi, 2019; Gutman & Akerman, 2008; Metsäpelto et al., 2017). Thus, it can be assumed that intelligence will be an important factor in children's occupational aspirations. Although, there is not much research that raises the problem of intelligence and aspirations. Gaur and Mathur (1974) revealed that intelligence had a significant positive association with aspirations and school achievement only in the group of girls. In another study, Cooney and colleagues’ 2006 research revealed that future aspirations for self-independence after graduation are no different for adolescents with intellectual disabilities and borderline intellectual functioning who attended a mainstream school than for those who attended a segregated school. In the same study, differences were observed in relation to occupational aspirations. Compared with students from a segregated school, students from the mainstream school more often aspired to occupations requiring professional competence than physical work. However, taking into account the combined result of all students from both schools (segregated school and mainstream school), a significant advantage of aspirations aimed at physical work was revealed. Such a result demonstrates that individuals with intellectual disabilities and borderline intellectual functioning are aware of their limitations, which ultimately affects future aspirations. Lower cognitive ability is associated with occupational aspirations, which are characterized by lower prestige, extrinsic motivation and a typically male role (Moulton et al., 2018). It seems that intelligence, school achievements and aspirations can be closely related; for instance, intelligence significantly predicts the school achievements of children, which, in turn, are significantly related to aspirations. When, for example, intelligence was measured in a group with the same intellectual level, the relationship between school achievements and aspirations was non-significant (Handelsman, 1952), which confirmed the important role that intelligence plays in shaping aspirations. The present study examined how fluid intelligence is related to occupational aspirations in school age.

Occupational aspirations and developmental stage

Aspirations throughout life change depending on the developmental stage (Ginzberg, 1952; Gottfredson, 1981). There are more realistic aspirations amongst adolescents than children, which are associated with a more realistic assessment of their own resources and barriers, for instance, that come from the social context (Helwig, 2008; Peila-Shuster, 2015). Adolescents adapt their occupational aspirations to the type of schools they attend (Basler & Kriesi, 2019). If the school is more demanding, students have higher occupational status aspirations. This indicates that adolescents' occupational aspirations depend on their individual resources and barriers.

Two theories that relate to the development of aspirations over the course of life indicate that children's aspirations go through a phase of fantasy and mainly depend on their interests and desires; the aspirations of older children and adolescents depend more on their own skills and resources (Ginzberg, 1952; Gottfredson, 1981). However, the moment and mechanisms of this developmental change are not clear. Ginzberg (1952) assumed that aspirations are more fantastic before the age of 11 and are more realistic after the age of 11. Gottfredson (1981) indicated that children develop aspirations in four stages: based on strength (3–5 years), gender roles (6–8 years), social values (9–13 years) and personality traits (14 years and more). This study explored occupational aspirations in school-age children. It was assumed that occupational aspirations in older children would be more realistic than in younger children.

Occupational aspirations and gender

Gender is another important factor differentiating children's occupational aspirations. Compared to boys, girls have occupational aspirations that are more intrinsically motivated, for instance, because of social value, than extrinsically motivated, for instance, because of financial gain (Flouri et al., 2015). Another difference is related to the gender role—girls more often aspire to occupations typically female, such as teacher, hairdresser, singer, and boys aspire to typically male occupations, such as footballer, policeman and fireman (Moulton et al., 2018). Another difference relates to education and prestige associated with the occupation. Girls aspire more often than boys to occupations that are associated with higher education and prestige, such as doctor, veterinarian and teacher (Lee & Byun, 2019; Moulton et al., 2018). Gendered leisure time is related to occupational aspirations. When children spend more time exclusively with females, then they aspire to more feminine occupational aspirations in adolescence (Lee et al., 2018). Gender is an important factor differentiating occupational aspiration. In the current study, the relationship between gender and occupational aspiration was explored.

The present study

The above review of the scientific literature shows that aspirations depend on individual differences, gender and developmental stage. They also play an important role in the school activity of children; for instance, they are related to school achievements (Gutman & Akerman, 2008; Metsäpelto et al., 2017). In sum, the objectives of the current study were embodied in two research questions: (a) what are the relationships between occupational aspirations in school-age children to fluid intelligence? (b) what are the relationships between occupational aspirations in school-age children to grade and gender? First, it was assumed that intelligence would be positively associated with occupational aspirations that relate to higher education and require higher specialist knowledge. This is justified by the results of studies that confirm that aspirations depend on individual abilities and resources (Cooney et al., 2006; Moulton et al., 2018). Secondly, it was assumed that grade and gender would be significantly related to occupational aspirations. It was anticipated that gender would be significantly related to occupational aspirations with a gender role (Flouri et al., 2015; Moulton et al., 2018) and aspirations in older children would be more realistic than in younger children (Flouri et al., 2015; Ginzberg, 1952; Gottfredson, 1981).

Method

Participants and procedure

The study participants N = 394 (girls n = 194; boys n = 200; Mage = 9.53 years; SD = .88) were Polish primary school students between the ages of 8 and 11 (age 8 n = 52; age 9 n = 133; age 10 n = 158; age 11 n = 51; Grade 3 n = 247; Grade 4 n = 147). The eligibility criterion for the purposive sample was age. The current study was conducted during regular school lessons in the classroom and in group form. Prior to the study, consent in a face-to-face meeting was obtained from children, parents and headmasters. The data were collected by the researcher. Before the start of the research and during its implementation, it was ensured that all ethical standards related to conducting social research were respected, including information on the purpose of the research, anonymity and confidentiality. During the study, children completed a questionnaire related to occupational aspirations and a fluid intelligence test.

Measures

Occupational aspirations

The children were asked the following open-ended question: What occupation would you like to do in the future? Similar questions were used in previous studies with children (Hansen, 2012; Powers & Wojtkiewicz, 2004). Each participant could give one written answer. To achieve the aim of the study, the results of previous studies, which also measured occupational aspirations, were used to categorize the answers (Flouri et al., 2015; Fulcher, 2011; Martela et al., 2019; Moulton et al., 2018). The following categories of occupational aspirations were established: realism, femininity/masculinity, motivation, education, prestige and social trust. When allocating responses to categories and subcategories, the following data were used: economic activity of the Polish population in the last quarter of 2016 and employment in the national economy in 2018 (Central Statistical Office, 2016, 2018), public trust occupations in Poland (Polish Chamber of Engineers, 2008) and occupational prestige (Public Opinion Research Centre, 2013).

The following subcategories were created for the realism category (Central Statistical Office, 2018): non-rare occupation (occupation in the employed section employing more than .5 million of the Polish population, e.g. teacher, doctor, policeman); uncertain (I don't know answers or no answers); rare occupation (occupation in the employed section employing less than .5 million employed of the Polish population, e.g. sportsman, singer); fantasy occupation (e.g. hacker, crazy potato—the occupation was characterized by unreality); descriptive occupation (e.g. mother, happy—answers were characterized by a description of the state of mind or a description of some social role); the femininity/masculinity category were coded based on the percentage of working men and women amongst employed sections and by selected groups of occupations (Central Statistical Office, 2016): masculine (proportion of Polish working-age women in that occupation < 25% female, e.g. policeman), integrated (proportion of Polish working-age women in that occupation 25 to 74.9% female, e.g. doctor), feminine (proportion of Polish working-age women in that occupation > = 75% female, e.g. teacher); the motivation category (according to Deci & Ryan’s, 1985 theory): extrinsic (aspirations motivated by external goals such as fame, image, money, e.g. company president, footballer), extrinsic-intermediate (aspirations that could be motivated by external goals such as fame, image, money, e.g. singer, actress), neutral (aspirations that could not be assigned to any of the categories of motivation, e.g. farmer, electrician), intrinsic-intermediate (aspirations motivated by goals as affiliation, community contribution and personal growth e.g. doctor, veterinarian), the category of motivation did not include intrinsic subcategory, because on the basis of participants' responses, it was not possible to clearly define which answers should be in the intrinsic-intermediate or intrinsic—as a result, only the intrinsic-intermediate category was created; the education category (subcategories divided according to the level of education required in Poland to perform a given occupation): basic and vocational education (e.g. sportsman, electrician, hairdresser), secondary education (e.g. fireman, policeman), higher education (e.g. doctor, teacher); the prestige category—subcategories created on the basis of the ranking of adult Poles assessing occupational prestige (Public Opinion Research Centre, 2013): high (occupational prestige > 70%, e.g. doctor, teacher); average (occupational prestige 70% to 30%, e.g. engineer, IT specialist); low (occupational prestige = < 30%, e.g. sportsman, salesman); the social trust category—subcategories created on the basis of the ranking of adult Poles assessing the most trusted profession (Polish Chamber of Engineers, 2008): high trust (social trust > 15%, e.g. doctor, policeman), neutral (social trust 15% to 3%, e.g. lawyer, IT specialist), low trust (social trust < 3%, e.g. soldier, architect).

Fluid intelligence

Intelligence was measured using the Cattell Culture Fair Intelligence Test—version 2 (Weiß Weiß, 2006) in the Polish adaptation (Stańczak, 2013). The test measures fluid intelligence. On the basis of its results, it is possible to predict school achievements of children. The test consists of two parts, which contain four subtests (Series, Classification, Matrices and Topological inference). Individual tasks are wordless and require inductive reasoning. The time taken to complete individual subtests is limited (18 min for part 1 and 12 min for part 2). Fluid intelligence testing using this test can be performed using two parts of the test or only the first part of the test. The first part of the test was used in the current study. The reliability of the test in the adaptive study, analysed using internal consistency of the overall result and both parts of the test, depending on age, was not less than .80.

Data analysis

Data was analysed using SPSS version 25.0 for Windows. First of all, the percentage number of occupational aspirations preferred by children and divided by categories were counted. Secondly, to analyse the relationships between occupational aspirations in school-age children to fluid intelligence, age and gender, correlations analysis was made. Thirdly, the difference between the categories of occupational aspirations and gender, grade and level of intelligence was explored. Finally, a CATREG regression analysis was performed for qualitative data to explore the factors that predict children’s occupational aspirations.

Results

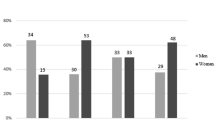

Table 1 presents the percentage number of occupational aspirations divided by occupations preferred by children (separately for all participants, gender and grade) and Table 2 contains the percentage number of occupational aspirations divided by categories and subcategories (separately for all participants, gender, grade and intelligence level—according to 25% percentiles). The most popular aspirations for boys were sports player (31.5%), IT specialist (7%) and policeman (6%); for girls, they were veterinarian (16%), performer (10.3%) and sports player (8.8%). Table 2 indicates that children aged 8–11 aspire to occupations that are non-rare (42.1%), extrinsic-intermediate motivated (48.3%) and have low social prestige (74.6%) and low social trust (66.3%). With regard to gender, girls aspire to occupations characterized by higher education (53.4%), both intrinsic (37.3%) and extrinsic-intermediate (41%) motivation, feminine (55.9%) and non-rare occupations (51%%). In turn, boys' aspirations are characterized by vocational and primary education (53.1%), extrinsic-intermediate motivation (55.6%), masculine (63.6%) and rare occupations (47%). Children with an intelligence level above 75% of the percentile (54.9%) and fourth graders (50.4%) more often aspire to occupations with higher education than children with an intelligence level below 25% of the percentile (44.3%) and third graders (43.1%) who aspire to occupations with primary and vocational education. A correlation analysis was performed using Spearman's rho. The results are presented in Table 3. Intelligence had a significant positive correlation only with education. All other categories of occupational aspirations were significantly related to each other.

In the next steps of the analysis, the difference between the categories of occupational aspirations and gender, grade and level of intelligence was examined. The results presenting the mean rank are in Table 4. It turned out that girls differ significantly from boys in aspirations in the areas of education (U = 9303.00; Z = −4.82; p < .001; r = .27), motivation (U = 8250.50; Z = −6.13; p < .001; r = .34), femininity/masculinity (U = 4923.50; Z = −10.29; p < .001; r = .57), social trust (U = 11,287.00; Z = −2.50; p < .05; r = .14) and realism (U = 10,432.00; Z = −3.58; p < .001; r = .20). The analysis of the girls' occupational aspirations in comparison with boys is characterized by higher education, higher intrinsic motivation, femininity role, higher social trust and higher realism of the occupation. Significant differences in the area of occupational aspirations due to education were observed for grade in school (U = 10,476.00; Z = −2.22; p < .05; r = .12). It was lower in the third grade than in the fourth grade. Differences at four levels of intelligence were examined and no significant differences were observed. To this end, it was decided to compare only two extreme groups, that is, below the 25% percentile and above the 75%. The results of the analyses revealed significant differences (U = 2480.00; Z = −2.42; p < .05; r = .19). Children from the first percentile aspired to occupations with a lower education than children from the fourth percentile. Similar results were obtained by comparing children with an intelligence level ranging between 25 and 50% percentile and above 75% percentile (U = 2307.00; Z = −2.03; p < .05; r = .17).

The factors that predict children’s occupational aspirations were examined. Three factors were studied: gender, grade and intelligence. For this purpose, a CATREG regression analysis was performed for qualitative data. The results are presented in Table 5. In the first model assessing realism, girls chose non-rare occupations and boys rare. In this model, gender explained 4% of the variability of the realism aspiration. In the second model, aspirations were also explained by gender in 33% of the variability of the femininity/masculinity. Boys were more closely associated with masculinity and girls with femininity. In the third model, aspirations due to the type of motivation were significantly predicted by gender, which explained 17% of them. Girls were associated with intrinsic motivation. In the fourth model, children’s occupational aspirations due to the level of education were significantly predicted by intelligence and gender. Children with higher intelligence and girls were associated with aspirations characterized by higher education. The whole model explained 11% of the dependent variable. In the fifth model, occupational aspirations due to social prestige were 3% predicted by gender. Girls were more closely associated than boys with high prestige. In the sixth and last model, occupational aspirations due to the degree of social trust were insignificantly explained by the introduced predictors F (3, 319) = 2.32; p > .05.

In order to further examine the role of intelligence in explaining children's occupational aspirations, it was decided to carry out a CATREG regression analysis separately by grade and age with the independent variable intelligence and the dependent variable education. The results are presented in Table 6. Intelligence significantly predicted education only in the fourth grade and explained 11% of the variability of the education variable. With age, intelligence significantly predicted education at the age of 10 and 11, with the relationship being stronger at age 11. At the age of 10, intelligence explained 5% and at the age of 11, intelligence explained 16% of the variability of the education variable.

Discussion

The present study examined whether the occupational aspirations of school-age children can be predicted by intelligence, gender and grade. Occupational aspirations were categorized as follows: realism, femininity/masculinity, motivation, education, prestige and social trust. The results indicated significant differences in the occupational categories in terms of intelligence, gender and grade.

The analyses revealed that children between the ages of 8 and 11 mostly prefer occupations that are realistic. Only two children amongst all the respondents declared a fantastic occupation and no children declared a descriptive occupation. The result indicates that children at this age base their occupational aspirations more on their interests and desires than fantasies. In addition, a comparable percentage of children chose rare or non-rare future occupations. This suggests that some children may not yet consider their skills, resources and the limitations of the environment when assessing their occupational aspirations and instead be guided by their interests and desires. However, it should be noted that almost the same proportion of children declare future occupations that are non-rare, which indicates that they are guided by their skills and abilities in assessing aspirations. This result suggests that children begin to take their skills into account when choosing occupations a little earlier than adolescence (Ginzberg, 1952; Gottfredson, 1981).

Another characteristic feature of occupational aspirations for this age is the advantage of extrinsic motivation in declared occupations; that is, that children are guided more when choosing occupations by an external reward, for instance, in the form of social approval, profit or power. This may be confirmed by the results of scientific studies that indicate that the extrinsic motivation of children in the primary grade of primary school is higher and decreases in later grades, which may be the result of the growing need for autonomy (Lepper et al., 2005; Rufini et al., 2012).

In the current study, the children aspired much less often to occupations which, in the opinion of adult Poles, were characterized by high social prestige and high social trust. This result revealed that it is likely that other occupations are prestigious for children than for adults and that children are guided by individual values in choosing occupations, rather than social utility that is more characteristic of public trust occupations. For example, a decrease of individualism and egocentrism with the next developmental stage is observed (Dumontheil et al., 2010; Hoffmann et al., 2015; Repacholi & Gopnik, 1997; Steinbeis et al., 2015). The obtained result may also indicate that the aspirations of children aged 8–11 do not depend so much on the inability to assess their own resources and limitations, but on following their own desires and current interests rather than distant goals.

The current study revealed that girls have higher occupational aspirations than boys related to higher education, higher intrinsic motivation, femininity, higher social trust and higher realism. Moreover, gender significantly predicted aspirations due to education, motivation, femininity/masculinity and realism. The obtained results indicate that the very important role played by gender in shaping the occupational aspirations of school-age children and not only at the age of 6–8 years (Ginzberg, 1952; Moulton et al., 2018). The occupational aspirations of girls compared to boys are characterized by higher intrinsic motivation, which is consistent with the study of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation in the school area (Rufini et al., 2012; Schoon, 2001). This is reflected in the girls' higher school achievement compared to boys (Freudenthaler et al., 2008; Israel et al., 2019). Girls’ aspirations were more realistic than boys' aspirations. This indicates that in comparison with boys, girls assess their capabilities more rationally and boys are guided by dreams and overestimate their capabilities; for instance, they aspire to be president of the company, astronaut, football star (Moulton et al., 2018). Girls more often than boys also chose occupations that were characterized by greater social trust in the opinion of adults. Such a result may indicate that girls are more guided by social values than boys when choosing aspirations. This may be due to the higher emotional and social competences of girls at this age compared to boys, which can be expressed through greater agreeableness and a higher self-efficacy in social situations (Nikel, 2020; Özgülük & Erdur-Baker, 2010).

Previous research results have indicated that career aspirations change over the course of children's development (Ginzberg, 1952; Gottfredson, 1981). It is not clear, however, exactly when children begin to assess their aspirations more realistically, for instance, in relation to their abilities and resources (Cooney et al., 2006; Moulton et al., 2018). The current study provided some evidence of when that could be. The results indicated that intelligence significantly predicted the area of occupational aspirations due to education. Students with higher intelligence aspired to occupations with higher education. It should be noted that the higher the education, the more specialized knowledge is required, which in turn requires the possession of appropriate skills and resources. The study analyses also revealed significant differences in the area of occupational aspirations related to education between children below the 25% percentile and above the 75% percentile. Children with a lower level of intelligence more often than children with a high level of intelligence aspired to occupations characterized by primary and vocational education. Similar results were obtained by Cooney et al. (2006) but only in the group of adolescents. The results of regression analysis and differences between groups indicated that intelligence plays an important role in shaping children's occupational aspirations, and children themselves are able to assess their individual capabilities and aspire to such occupations that are compatible with their resources and abilities. Further analysis indicated that the relationship between intelligence and the area of occupational aspirations due to education is only significant from the fourth grade and 10 years of age. This suggests that between the third and fourth grades and between 9 and 10 years of age, there is a certain breakthrough in intellectual development that contributes to a more realistic assessment of cognitive capabilities, which is reflected in more adequate and realistic aspirations. This result probably argues that in occupational aspirations characterized by some realism, the ability of children to assess their individual resources appears slightly earlier than in adolescence, at around 11–12 years of age (Creed et al., 2007; Ginzberg, 1952).

Conclusion

The current study reveals some of the first evidence of how occupational aspirations are related to fluid intelligence, particularly amongst school-age children. In addition, it indicates the role of gender in shaping occupational aspirations. However, the study has some limitations. The selection of individuals for the study was intentional—children of primary schools aged 8–11 in Poland participated in the study. Future studies should be extended to other research groups, although it is worth noting that some of the results obtained, for instance, those related to the role of gender in shaping occupational aspirations, were consistent with studies carried out in other cultures (Flouri et al., 2015). When creating categories of occupational aspirations, as Moulton et al. (2018) indicated, it is not entirely certain that the choice of such occupations by children was intrinsically motivated or associated with greater social prestige. Consequently, some conclusions presented in the discussion should be interpreted cautiously. However, this creates suggestions for further research, like, trying to answer how intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is related to occupational aspirations or what occupations are considered prestigious in the children’s opinions. As revealed in the study, intelligence itself explained the occupational aspirations categorized by education in the range of 5%–16%, more with increasing age. This suggests that there are other important variables that may be important in predicting occupational aspirations, such as resilience (Sanders et al., 2017), which depends on a child’s own resources and resources in the environment. In the current study, socioeconomic status, nationality, profession of the parent were uncontrolled. Future studies should include more demographical information.

The results obtained in the present study make a significant implication to career development theorists (Ginzberg, 1952; Gottfredson, 1981). The current study revealed that fluid intelligence significantly predicted occupational aspirations due to education, which may indicate that school-age children are guided by knowledge about their individual capabilities in choosing their occupational aspirations and not, as previously indicated, mainly by their gender role or their own needs and interests (Creed et al., 2007; Ginzberg, 1952). Furthermore, fluid intelligence has been predicting occupational aspirations for only 10 years, which may indicate some important development moment in shaping aspirations.

Another significant implication is about understanding the role that gender plays in affecting the occupational aspirations of school-age children. Gender predicted occupational aspirations, such as those characterized by realism, motivation, social trust, femininity/masculinity, which may indicate that occupational aspirations may depend, on the one hand, on played social roles and, on the other hand, on personality traits. To sum up, gender differences in occupational aspirations in school-age children probably come from the interaction between gender socialization and individual differences, e.g. in motivation, personality traits, cognitive ability (Hughes, 2016; Moulton et al., 2018; Widlund et al., 2020).

References

Ansong, D., Eisensmith, S. R., Okumu, M., & Chowa, G. A. (2019). The importance of self-efficacy and educational aspirations for academic achievement in resource-limited countries: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Adolescence, 70, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.11.003

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development, 72(1), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00273

Basler, A., & Kriesi, I. (2019). Adolescents’ development of occupational aspirations in a tracked and vocation-oriented educational system. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115, 103330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103330

Carroll, A., Houghton, S., Wood, R., Unsworth, K., Hattie, J., Gordon, L., & Bower, J. (2009). Self-efficacy and academic achievement in Australian high school students: The mediating effects of academic aspirations and delinquency. Journal of Adolescence, 32(4), 797–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.009

Cattell, R. B. (1971). Abilities: Their structure, growth and action. Houghton-Mifflin.

Central Statistical Office. (2016). Labour force survey in Poland. Retrieved from https://stat.gov.pl/.

Central Statistical Office. (2018). Employment in national economy in 2018. Retrieved from https://stat.gov.pl/.

Cooney, G., Jahoda, A., Gumley, A., & Knott, F. (2006). Young people with intellectual disabilities attending mainstream and segregated schooling: Perceived stigma, social comparison and future aspirations. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(6), 432–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00789.x

Creed, P. A., Conlon, E. G., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). Career barriers and reading ability as correlates of career aspirations and expectations of parents and their children. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(2), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.11.001

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

Dumontheil, I., Apperly, I. A., & Blakemore, S. J. (2010). Online usage of theory of mind continues to develop in late adolescence. Developmental Science, 13(2), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00888.x

Flouri, E., Tsivrikos, D., Akhtar, R., & Midouhas, E. (2015). Neighbourhood, school and family determinants of children’s aspirations in primary school. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.12.006

Fraser, M., & Garg, R. (2014). Educational aspirations. Encyklopedia of Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1695-2_147

Freudenthaler, H. H., Spinath, B., & Neubauer, A. C. (2008). Predicting school achievement in boys and girls. European Journal of Personality: Published for the European Association of Personality Psychology, 22(3), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.678

Fulcher, M. (2011). Individual differences in children’s occupational aspirations as a function of parental traditionality. Sex Roles, 64(1–2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9854-7

Gaur, J. S., & Mathur, P. (1974). The effect of level of intelligence on the occupational aspirations of the higher secondary school students in Delhi. Indian Journal of Psychology, 49(2), 139–148.

Ginzberg, E. (1952). Toward a theory of occupational choice. Occupations: the Vocational Guidance Journal, 30(7), 491–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-5892.1952.tb02708.x

Goldenberg, C., Gallimore, R., Reese, L., & Garnier, H. (2001). Cause or effect? A longitudinal study of immigrant Latino parents’ aspirations and expectations, and their children’s school performance. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 547–582. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038003547

Gorard, S., See, B. H., & Davies, P. (2012). The impact of attitudes and aspirations on educational attainment and participation. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Gottfredson, L. S. (1981). Circumscription and compromise: A developmental theory of occupational aspirations. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28(6), 545. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.28.6.545

Gutman, L., & Akerman, R. (2008). Determinants of aspirations [wider benefits of learning research report no. 27]. Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning, Institute of Education, University of London.

Handelsman, I. (1952). The relationship between occupational level (OL) scores and various measures of aspiration and achievement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 66(10), 13. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093611

Hansen, K. (2012). Millennium cohort study: First, second, third and fourth surveys. A guide to the datasets (7th ed.). Centre for Longitudinal Studies.

Helwig, A. A. (2008). From childhood to adulthood: A 15-year longitudinal career development study. The Career Development Quarterly, 57(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2008.tb00164.x

Hoffmann, F., Singer, T., & Steinbeis, N. (2015). Children’s increased emotional egocentricity compared to adults is mediated by age-related differences in conflict processing. Child Development, 86(3), 765–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12338

Hughes J. M. (2016). Occupational aspirations. In: Levesque R. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32132-5_219-2

Israel, A., Lüdtke, O., & Wagner, J. (2019). The longitudinal association between personality and achievement in adolescence: Differential effects across all Big Five traits and four achievement indicators. Learning and Individual Differences, 72, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.03.001

Kewalramani, S., & Phillipson, S. (2020). Parental role in shaping immigrant children’s subject choices and career pathway decisions in Australia. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20, 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09395-2

Kvist, A. V., & Gustafsson, J. E. (2008). The relation between fluid intelligence and the general factor as a function of cultural background: A test of Cattell’s Investment theory. Intelligence, 36(5), 422–436.

Lee, B., & Byun, S. Y. (2019). Socioeconomic status, vocational aspirations, school tracks, and occupational attainment in South Korea. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(8), 1494–1505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01056-5

Lee, B., Skinner, O. D., & McHale, S. M. (2018). Links between gendered leisure time in childhood and adolescence and gendered occupational aspirations. Journal of Adolescence, 62, 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.10.011

Lepper, M. R., Corpus, J. H., & Iyengar, S. S. (2005). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: Age differences and academic correlates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.184

Lv, B., Zhou, H., Liu, C., Guo, X., Zhang, C., Liu, Z., & Luo, L. (2018). The relationship between mother–child discrepancies in educational aspirations and children’s academic achievement: The mediating role of children’s academic self-efficacy. Children and Youth Services Review, 86, 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.010

Martela, F., Bradshaw, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2019). Expanding the map of intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations using network analysis and multidimensional scaling: Examining four new aspirations. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 2174. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02174.

Metsäpelto, R. L., Silinskas, G., Kiuru, N., Poikkeus, A. M., Pakarinen, E., Vasalampi, K., Lerkkanen, M.-K., & Nurmi, J. E. (2017). Externalizing behavior problems and interest in reading as predictors of later reading skills and educational aspirations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 324–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.03.009

Moulton, V., Flouri, E., Joshi, H., & Sullivan, A. (2018). Individual-level predictors of young children’s aspirations. Research Papers in Education, 33(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1225797

Nikel, Ł. (2020). Submissiveness, assertiveness and aggressiveness in school-age children: The role of self-efficacy and the Big Five. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, Article 104746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104746.

Özgülük, S. B., & Erdur-Baker, Ö. (2010). Gender and grade differences in children’s alternative solutions to interpersonal conflict situations. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 511–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.134

Peila-Shuster J. J. (2015) Career development for children. In K. Maree & A. D. Fabio (Eds.), Exploring new horizons in career counselling. Sense Publishers.

Polish Chamber of Engineers. (2008). Public trust professions according to Poles. Retrieved from https://www.piib.org.pl/.

Powers, R. S., & Wojtkiewicz, R. A. (2004). Occupational aspirations, gender, and educational attainment. Sociological Spectrum, 24(5), 601–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732170490448784

Public Opinion Research Center. (2013). Occupational prestige. Retrieved from https://www.cbos.pl/.

Pulkkinen, L. (2001). Reveller or striver? How childhood self-control predicts adult behavior. In A. C. Bohart & D. J. Stipek (Eds.), Constructive & destructive behavior: Implications for family, school, & society (pp. 167–185). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10433-008.

Repacholi, B. M., & Gopnik, A. (1997). Early reasoning about desires: Evidence from 14-and 18-month-olds. Developmental Psychology, 33(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.1.12

Rudasill, K., Prokasky, A., Tu, X., Frohn, S., Sirota, K., & Molfese, V. (2014). Parent vs. teacher ratings of children’s shyness as predictors of language and attention skills. Learning and Individual Differences, 34, 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.05.008

Rufini, S. É., Bzuneck, J. A., & Oliveira, K. L. D. (2012). The quality of motivation among elementary school students. Paidéia (ribeirão Preto), 22(51), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-863X2012000100007

Sanders, J., Munford, R., & Boden, J. M. (2017). Pathways to educational aspirations: Resilience as a mediator of proximal resources and risks. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 12(2), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2017.1367312.

Schoon, I. (2001). Teenage job aspirations and career attainment in adulthood: A 17-year follow-up study of teenagers who aspired to become scientists, health professionals, or engineers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25(2), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250042000186

Sheldrake, R. (2020). Changes in children’s science-related career aspirations from age 11 to age 14. Research in Science Education, 50, 1435–1464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-018-9739-2

Spearman, C. (1927). The abilities of man. MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1038/120181a0

Stańczak, J. (2013). CFT 20-R Neutralny Kulturowo Test Inteligencji Cattella—wersja 2 zrewidowana przez R. H. Weiβa we współpracy z B.Weiβem. Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP.

Steinbeis, N., Bernhardt, B. C., & Singer, T. (2015). Age-related differences in function and structure of rSMG and reduced functional connectivity with DLPFC explains heightened emotional egocentricity bias in childhood. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10(2), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsu057

Trebbels, M. (2015). The concept of educational aspirations. In The transition at the end of compulsory full-time education (pp. 37–45). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06241-5_3.

Weiß, R. H., & Weiß, H. R. (2006). Cft 20-r. Grundintelligenztest Skala, 2.

Widlund, A., Tuominen, H., Tapola, A., & Korhonen, J. (2020). Gendered pathways from academic performance, motivational beliefs, and school burnout to adolescents’ educational and occupational aspirations. Learning and Instruction, 66, Article 101299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101299.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nikel, Ł. Exploring occupational aspirations of school-age children by fluid intelligence, gender and grade. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance 23, 1–18 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09497-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09497-w