Abstract

The spread of fake news poses a global challenge to society, as this deliberately false information reduce trust in democracy, manipulate opinions, and negatively affect people’s health. Educational research and practice must address this issue by developing and evaluating solutions to counter fake news. A promising approach in this regard is the use of game-based learning environments. In this study, we focus on Escape Fake, an augmented reality (AR) escape game developed for use in media literacy education. To date, there is limited research on the effectiveness of the game for learning about fake news. To overcome this gap, we conducted a field study using a pretest-posttest research design. A total of 28 students (14 girls, mean age = 14.71 years) participated. The results show that Escape Fake can address four learning objectives relevant in fake news detection with educationally desired effect sizes: Knowledge acquisition (d = 1.34), ability to discern information (d = 0.39), critical attitude toward trustworthiness of online information (d = 0.53), and confidence in recognizing fake news in the future (d = 0.41). Based on these results, the game can be recommended as an educational resource for media literacy education. Future research directions are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The spread of misinformation and disinformation, so-called fake news, on social media and the Internet is a challenge for societies worldwide, as it can affect the way people live together. Fake news can reduce the trust in democratic institutions and scientific findings, manipulate voters’ opinions, and reinforce skepticism of legitimate and public information providers (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; Lewandowsky et al., 2017; Traberg et al., 2022).

Most currently, the danger of fake news was demonstrated during the Coronavirus crisis: With the beginning of the epidemic situation, the spread of false information about the Coronavirus dramatically increased, for example, regarding the origin of the virus or actions that should protect against an infection. The director of the World Health Organization (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said that “We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic” (Barzilai & Chinn, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). Moreover, false news about the vaccination against the Coronavirus weakens people’s confidence in the effectiveness of the vaccination leading to its rejection. Thus, fake news spread online can result in real health consequences (van der Linden, 2022).

Although spreading misinformation and disinformation is not a completely new phenomenon (e.g. Zarocostas, 2020), the possibility to easily share information online has increased the problem. For example, studies showed that fake news are shared more often on social media platforms compared to legitimate news (Cooke, 2017) and that it is challenging for users to discern real from false online information (Kahne & Bowyer, 2017).

Chinn et al. (2021) get to the point when they write that media environments in the increasingly digital world are complex and epistemically unfriendly (p. 51). Consequently, in education, learning environments are needed that prepare learners to navigate these complex media environments. Barzilai and Chinn (2020) summarize the following relevant learning objectives, the importance of which is also emphasized in other studies on media literacy (Apuke et al., 2022; Jones-Jang et al., 2021; Vraga & Tully, 2021):

Like in general media and digital literacy education (e.g. Baron, 2019), Barzilai and Chinn (2020; also Apuke et al., 2022) argue for the promotion and the development of knowledge and abilities necessary to identify and discern real from false online information. For example, learners should know tools for analyzing online content, e.g., the reverse image search (Illinois University Library, 2020), and should be able to critically interpret online sources.

Further, Barzilai and Chinn (2020) recommend fostering scientific literacy, for example, through the evaluation of scientific communication and/or engaging learners in scientific projects learning how researchers work when they investigate questions of interest.

Beyond these more knowledge and ability-related learning objectives, Barzilai and Chinn (2020) point out that attitudes and beliefs should be addressed in instruction dealing with fake news (also Vraga & Tully, 2021). For example, learners should be epistemically vigilant, i.e., being critical regarding the trustworthiness of online sources, and should be aware of biases limiting their own thinking.

A promising approach to achieve the outlined learning objectives in media literacy education focusing on how to fight fake news is the use of game-based and playful learning environments (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019b; Yang et al., 2021b).

1.1 Playful Learning against Fake News

Game-based and playful learning is a multidimensional instructional approach, engaging learners affectively, cognitively, behaviorally, and socially in the learning process (Plass et al., 2015). Thus, educational games can be used to address a variety of learning objectives, like cognitive (knowledge, skills), affective (e.g. attitudes, motivation), and behavioral (e.g. behavioral change, physiological) learning outcomes (Boyle et al., 2016; Plass et al., 2020). The effectiveness of game-based and playful learning environments to learn how to conquer fake news was examined in several studies:

Roozenbeek and van der Linden (2019a) developed the card game Fake News Game and evaluated its effectiveness with secondary school students. In the game, the students engage in a role play and design fake news to convince the other players of their own point of view. Compared to a control group without any fake news instruction, the students in the card game condition were significantly better able to judge the reliability of fake news article.

In another study, Roozenbeek and van der Linden (2019b) developed the freely accessible online game Bad News. In the game, the players act as fake news creators trying to collect as many followers as possible. At the same time, the players need to monitor their credibility score to finally run a fictional fake news empire. Evaluation of the game was done with a pretest-posttest design including data from approximately 14.000 participants. The results show that after playing the game the participants were significantly better able to rate the reliability of Twitter postings then before; the effect is with η2 = 0.27 of large size.

Basol et al. (2020) confirmed the effectiveness of the Bad News game regarding the ability to discern real from false information. Furthermore, Basol et al. (2020) provide evidence that the game-based learning approach strengthens learners’ confidence in being able to recognize fake news in the future. Higher confidence was also found when playing the Harmony Square game (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2020).

Scheibenzuber et al. (2021) designed and evaluated a problem-based online course addressing fake news about migration. Results from the pretest-posttest design show that the course improved students’ ability to judge the trustworthiness of news reports with a large effect size (η2 = 0.64).

Yang et al. (2021b) developed an educational online game called Trustme! and investigated its effectiveness measuring two learning outcomes: First, in accordance with the already mentioned studies (Basol et al., 2020; Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019b); Roozenbeek & Linden, 2019a); Yang et al., (2021b) assessed learners’ information discernment skills after playing the game. Results show that compared to two control conditions the learners playing Trustme! were significantly better able to discern real from false information. Yang et al. (2021b) assessed learners’ skepticism towards online information after playing the game. Compared to the two control conditions, no significant differences were detected. Yang et al. (2021b) explain this result with the limitations of an online game.

Although this overview of previously developed and evaluated game-based interventions provides promising results regard the effectiveness of games to learn about fake news, several questions remain open. For example, in Yang et al. (2021b) playing a game was not able to address the attitudinal learning outcome of skepticism. Hence, more research is necessary considering attitudinal learning in fake news instruction. Further, the summarized studies determine the effectiveness of the developed games on one or two learning outcomes relevant in fighting fake news. However, no study examined if playing a game increases participants knowledge about fake news. As knowledge is the basis for future problem-solving (Tricot & Sweller, 2014), such as identifying fake news on social media, it is important to test if games can also contribute to knowledge acquisition.

Furthermore, mostly, researchers used fully online games (with the exception of the card game in Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019a).

In contrast, Paraschivoiu et al. (2021) developed a hybrid game for fighting fake news, Escape Fake, using augmented reality (AR) technology. Additionally, compared to the reviewed studies, Paraschivoiu et al. (2021) used a different genre of game-based learning that recently found its way into the classroom, namely the escape the room gameplay.

Since the focus of this study is on the effects of Escape Fake, we will discuss next research on escape games and learning followed by a detailed account of the Escape Fake game.

1.2 Escape Games and Learning

Escape the room games, or escape games, are well-known in the entertainment sector. Traditionally, a group of people is locked into one room or several related rooms, aiming to escape the room(s) by solving puzzles in a given amount of time. If time runs out, the game is lost. Further, in escape games players take on the role of fictious characters which have to fulfill a mission, like solving the world or defusing a bomb (Nicholson, 2015).

Recently, educators adopted the escape game idea to provide immersive and playful learning experiences in the classroom. Due to the lack of space given in traditional classrooms and ethical concerns of locking students into a room until they puzzle their way out (Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019), educators and researchers use analog and digital materials to realize the escape game idea. For example, Veldkamp et al. (2020) developed a physical box in which students had to break in by solving puzzles hiding codes for locks attached to the box. Further, the authors used videos to immerse the learners in the story of the game (Veldkamp et al., 2020). Estudante and Dietrich (2020) developed a mobile escape game based on QR codes and augmented reality (AR) technology. AR simulated different rooms in which the students interacted with virtual objects by using a tablet or a smartphone. Klamma et al. (2020) designed an AR escape game experienced by students through AR glasses resulting in a highly immersive and enjoyable learning experience. Another approach is the simulation of the escape the room gameplay in entirely digital games (Makri et al., 2021). For example, Neumann et al. (2020) used an online tool to provide an interactive story enriched by puzzles in a course with preservice teachers. Through pointing and clicking the players worked on the puzzles and after successful completion new virtual locations were entered. In a study by Buchner et al. (2022), a professional learning software was used for developing a digital escape game on how to use open educational resources.

From an instructional perspective, researchers and practitioners alike assume that the combination of hands-on and minds-on activities embedded in an engaging story can promote cognitive (e.g. knowledge acquisition), affective (e.g. motivation), and psychomotor (e.g., skills acquisition) learning outcomes (Bassford et al., 2016; Franco & DeLuca, 2019; Hermanns et al., 2017; Veldkamp, Knippels et al., 2021b). Further, immersion experience, defined as a deep cognitive and emotional involvement during playing (Georgiou & Kyza, 2017, 2018), is expected to enhance student engagement and, consequently, learning when using escape games (Lopez-Pernas et al., 2019; Monaghan & Nicholson, 2017; Nicholson, 2018).

However, evidence for the effectiveness of educational escape games is scarce and contradictory (Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019; Makri et al., 2021; Veldkamp et al., 2020b).

For example, Cotner et al. (2018) and Hou and Li (2014) found no significant differences in knowledge tests in a pretest-posttest comparison. In Clauson et al. (2019), learners performed worse on the posttest than on the pretest. Teachers and students in a study conducted by Veldkamp et al. (2021a) reported that the time limit of an escape game for biology education triggers pressure and prevents a more intensive engagement with the content. Therefore, both teachers and learners doubt the learning effectiveness of escape games.

In contrast, von Kotzebue et al. (2022) and Lopez-Pernas et al. (2019) found positive effects of playing an escape game with significant improvements in pretest-posttest designs and corresponding large effect sizes.

From a theoretical perspective, these contradictory results can be explained by referring to cognitive load theory (CLT; Sweller et al., 2019): Escape games, like other (computer) games, are problem-based learning environments, which can be emotionally engaging but cognitively demanding for learners without instructional support (Buchner et al., 2022; Mayer, 2019). According to CLT, problem-based learning environments increase extraneous cognitive load (Kirschner et al., 2006), also known as unproductive cognitive load, while decreasing productive cognitive processing. However, the latter is necessary to ensure that new information is processed in working memory by integrating prior knowledge from and transferring new knowledge to long-term memory (Paas & van Merriënboer, 2020; Sweller et al., 2019).

In a previous study, for instance, Buchner et al. (2022) provided evidence that learning with a digital escape game can be enhanced when applying CLT. Also, in the studies by Veldkamp and colleagues the results indicate that cognitive overload might be responsible for the lack of learning gains when studying with escape games. Consequently, the authors recommend a balance of challenge and scaffold when designing educational escape games (Veldkamp et al., 2020; Veldkamp, Merx et al., 2021a).

1.3 Escape Fake

Escape Fake is an augmented reality (AR) escape game developed by an interdisciplinary team for the use in media literacy education. The target group are students aged between 12 and 18 years (Paraschivoiu et al., 2021).

In contrast to other fake news games, Escape Fake is a hybrid learning space (Veldkamp et al., 2020), combining real world elements with virtual objects. From a technological perspective, AR technology is applied to blend reality with virtuality. AR is a highly interactive visualization technology that can be used, for example, to overlay printed materials with additional digital information that is shown on the display of a mobile device (Azuma et al., 2001). For educational purposes, AR can situate learners in a relevant context, enables gesture-based and whole-body interactions with both real and virtual objects, and evokes a sense of spatiality (Krüger et al., 2019). Therefore, like mentioned in other studies (Klamma et al., 2020; Wild et al., 2021), AR is particularly suitable for use in escape games; for instance, to simulate rooms and to solve riddles using both analog and digital objects.

In Escape Fake, marker-based AR technology is used to simulate different rooms. This means, for playing the game printed images, so-called markers, are needed that contain the virtual information. For example, one marker simulates an office with a desk and a computer. To see the office, users open the freely available Escape Fake application, point the camera onto the marker, and the virtual objects appear on the display (Fig. 1). Through clicking, dragging, and dropping, players interact with the virtual objects. For example, players collect objects in a virtual inventory and combine them during the game to solve riddles (Paraschivoiu et al., 2021). In total, there are five rooms to explore with objects to inspect; all marker-images are freely available via escapefake.org (see also Polycular, 2020).

The gameplay of Escape Fake follows the idea of escape the room games. As summarized in Sect. 1.2, escape games can immerse learners into an exciting story resulting in high engagement and emotional involvement. On the other hand, escape games are problem-based learning environments which can easily overload learners working memory capacity and, thus, hinder the acquisition of new knowledge

With this in mind, Escape Fake was specifically developed as an educational escape game making instructional scaffolds an integral part of the story.

The game starts with a friend request on social media from Hannah Lee May. She introduces herself as a reverse history hacker coming from a dystopian, not-too-distant future searching for fellows helping her to avoid the escalation of fake news. In total, two crucial situations in history must be changed to fix the future. The two situations are represented in Escape Fake as two escape games called “The Bus Situation” and “The Climate Ambitions” (Paraschivoiu et al., 2021). In this study, we focus on the first game, “The Bus Situation”, so the following details refer only to this room.

In “The Bus Situation”, a bus driver is accused of human trafficking in social media. Accordingly, bookings collapse, and his company is at risk of going bankrupt. Together with Hannah Lee May, the player(s) collect evidence to restore the reputation of the bus driver. To do so, several puzzles need to be solved within a 25-minute time limit. For example, the players must find a password to enter a computer and must reconstruct the last jobs of the bus driver to show that he is not a human trafficker.

During the game, Hannah Lee May act as a pedagogical agent accompanying and scaffolding the player(s) by providing tips on how to solve the puzzles or what purpose collected items might have. For example, when the player(s) collect a hammer, Hannah Lee May advises that it can be used to smash other objects. The presence of Hannah Lee May makes Escape Fake a guided game, so that the risk of cognitive overload and frustration, as occurs in many purely exploratory games for learning (Mayer, 2019; Westera, 2019), is prevented. From a technological perspective, Hannah Lee May was implemented as a chatbot (Paraschivoiu et al., 2021).

Furthermore, after successfully solving a puzzle, time stops, and a multiple-choice quiz appears. In the quizzes, information about fake news design and ways to discern real from false news is instructed. For example, players are taught that misinformation and disinformation usually concern particularly controversial topics and aim to trigger emotions such as fear or anger. In addition, it is taught that in the case of particularly emotionalizing and spectacular postings on the Internet, the original source must be examined. For example, the imprint can be used to find out whether a reputable news provider is involved or not. The main aim of the quizzes is to deliver basic knowledge on the topic that can be applied to solve problems in new situations. For example, with the help of knowledge about the imprint it is expected that players will search for an imprint when navigating an unknown website.

Since images are also increasingly being manipulated, Escape Fake game also shows how the reverse image search can be used. For this purpose, the players in the game upload the image of the bus driver to such a search engine and find out that the image has been edited afterwards.

Stopping the time is particularly important, as this on the one hand grants an in-depth thinking without pressure about the content presented in the quizzes, and on the other hand does not undermine the game goal of “breaking out of the room” in the given time. It is expected that this balance will support productive cognitive processing while not diminishing the motivating effect of the game.

In a first study, Paraschivoiu et al. (2021) investigated whether the target group perceived the game as challenging but feasible and whether it could be used to learn about fake news. The results were promising regarding motivational aspects like immersion experience; however, there was a lack of measurement of learning outcomes. In a more recent study, Buchner and Höfler (2024) determined if the game can promote learning about fake news in teacher education. However, results on learning outcomes considering the target group of the Escape Fake game are still lacking. This study aims to fill this knowledge gap.

1.4 Aim of the Study and Research Questions

Previous research indicates that playful learning environments are effective for learning about fake news. However, no results for AR (escape) games on the topic are available and no study has investigated if using a game can enhance knowledge about fake news. Further, an evaluation of the effectiveness of Escape Fake is lacking. Furthermore, research on the (potential) benefits of educational escape games on learning outcomes beyond motivation, immersion, and engagement is in its infancy (Makri et al., 2021; Veldkamp et al., 2020b). Therefore, this study contributes to both the literature on learning about fake news with games and the more general literature on learning with escape games.

To do so, this study investigates the effect of playing the AR escape game Escape Fake on learning objectives that are relevant in instruction how to fight fake news. Based on the literature on educational solutions and recommendations (Barzilai & Chinn, 2020; Chinn et al., 2021) as well as playful learning environments to counter fake news (e.g. Basol et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021b), we defined four learning objectives examined in this study:

-

Following Barzilai and Chinn (2020), we examine whether Escape Fake can teach basic knowledge about fake news:

RQ1

Does playing Escape Fake promote the acquisition of knowledge about fake news?

-

Drawing on Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019a); Roozenbeek & Linden, 2019b); Yang et al. (2021b), we assess whether playing Escape Fake promotes learners’ ability to discern real from false information:

RQ2

Does playing Escape Fake promote information discernment ability?

-

Based on Barzilai and Chinn (2020); Yang et al. (2021b), we test the effect of Escape Fake on an affective learning outcome, namely learners’ attitudes toward the trustworthiness of online information:

RQ3

Does playing Escape Fake promote a more critical attitude toward online information?

-

Following Basol et al. (2020) and Roozenbeek and van der Linden (2020), we examine whether playing Escape Fake can improve confidence in recognizing fake news:

RQ4

Does playing Escape Fake promote learners’ confidence in recognizing fake news in the future?

2 Method

2.1 Participants and Design

To investigate the research questions, we conducted a field study with a pretest-posttest design. Participants were 28 school students (14 girls) from a gymnasium, a kind of high school preparing students for university, in the west of Germany with a mean age of 14.71 (SD = 1.88) years. The students participated voluntarily during their regular class time. The school principal approved the study, and the parents were also informed and gave their consent. Consent to participate was also obtained from the students. The students were also informed that non-participation would not have any negative consequences. Further, the study had no influence on the students’ grades.

Data were collected before and after playing the Escape Fake AR escape room game using an online questionnaire developed with SoSci Survey (Leiner, 2019). The data collection was completely anonymized and pseudonymized so that no conclusions can be drawn about individuals. The guidelines of good scientific practice were observed during the implementation and ethical guidelines for research in the field of education were followed.

The decision regarding a research design without a control group was based on the following considerations:

First, we followed the recommendation for research on games for learning provided by Mayer (2014, pp. 42–43): Using an ineffective game in research projects including control conditions is useless; hence, if no empirical evidence is available on the effectiveness of the game under investigation, initial field testing is necessary before conducting further studies.

Second, as researchers in the field of instructional design and educational technology, we share previously raised concerns regarding empirical studies mainly interested in proving if one approach is more effective than another (Honebein & Reigeluth, 2021). This is particularly problematic in research investigating learning with immersive technologies like AR and virtual reality as this perspective results in endless numbers of confounding media comparison studies (Buchner & Kerres, 2023; Glaser & Moore, 2023; Mulders, 2023). Therefore, we aim to determine how to improve learning with the Escape Fake game. However, before we can to this, piloting is necessary as mentioned in the first argument.

2.2 Instruments

2.2.1 Knowledge Acquisition

To assess students’ knowledge about fake news before and after playing the escape game, a test consisting of eight questions was developed based on the information delivered in Escape Fake (see Appendix A). An example question is “What is a hybrid-fake?” – A combination of real and fake information; Fake news about hybrid vehicles; A piece of information that is available both online and offline; Fake news that originated offline and only later found its way to the Internet.

The students answered each question by choosing one out of the four answers. In the pretest, the students could also choose the option “I do not know”. Each correct answer was rewarded with one point; hence, a maximum of eight points could be achieved in the knowledge acquisition test.

2.2.2 Information Discernment Ability

To measure students’ ability to discern real from false information in the pretest and the posttest, we used four simulated social media postings developed by German journalists (handysektor.de, 2017). Three of these postings were patterned after known design features of fake news, for example, addressing emotional content (e.g. migration) together with provocative pictures (e.g. damage playgrounds). Figure 2 shows an example of such a false posting. One posting used a restrained design and conformed to the standard of journalistic work. All postings are available via Appendix B.

Following the work of Roozenbeek and van der Linden (2019a, b), students had to judge the reliability of each news posting on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not reliable at all, 7 = very reliable).

An example for a news posting the students had to judge of its reliability. The picture simulates a social media posting from a social media site called “New Alternative”. On the picture, a playground with a smashed glass is visible. On the picture is written “Graffiti and destruction on the playground”. In the posting, the “New Alternative” writes that “Now not even our children are safe! What a scandal! Probably out of boredom: Migrants are up to mischief again.” This posting is an example for a fake news message

2.2.3 Attitude toward Online Information

To determine whether students felt that they were more vigilant and critical to information spread on social media platforms after the intervention, we used a modified version of the Information Verification Scale (IVS) developed by Nee (2019). The IVS consists of five items, for example, “I look at several sources to figure out whether I should believe it”, answered on a Likert scale from 1 = never to 7 = always (see Appendix C; Cronbach’s alpha pretest = 0.72, Cronbach’s alpha posttest = 0.82).

2.2.4 Confidence to Recognize Fake News

To assess whether students are more confident to recognize fake news after playing Escape Fake, we used a modified version – wording was adapted to the context of school students – of the Recognising Misinformation scale developed by Khan and Idris (2019). The scale consists of three items, for example, “I can check the truth of stories and news reports, e.g. with the help of other sources”, answered on a Likert scale from 1 = do not agree to 7 = fully agree (see Appendix D). Cronbach’s alpha values were not satisfactory in this study when using all three items: pretest = 0.57, posttest = 0.61. After deleting the second item, Cronbach’s alpha was satisfactory for the pretest (0.79) and the posttest (0.69).

2.3 Procedure

The study is designed as a field study and accordingly took place at the students’ school during regular class time. Contrary to regular lessons, learning with Escape Fake happened in the auditorium of the school because of the limited space in the classroom to place the markers on the walls as well as on the floor. Tablet computers with the Escape Fake application were prepared and provided by the research team. Further, the marker images were placed aforehand on different corners in the auditorium ensuring that each student had enough space walking around and inspecting all five simulated rooms. Figure 3 gives an example of a student playing the game.

After a brief introduction how to play the game, students gave their consent to participate in the study. Then, students answered the pretest with questions about gender and age, completed the three instruments, and started playing the AR escape game. Each participant played the game individually.

Once the game was completed, the students filled the posttest. In sum, the duration of the intervention was 90 min.

3 Results

For data analysis purposes, the items in all scales were aggregated using mean values. Three out of four information discrimination tasks were fake news; therefore, the values were recoded so that higher values represent correct reliability judgements.

For the knowledge acquisition test, each correct question was rewarded with one point and an overall sum was computed. A maximum of eight points could be achieved.

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for all four variables in the pretest and the posttest.

To test the effect of playing the Escape Fake AR escape game on the four variables, a paired samples t-test was computed with SPSS 28 software. The significance level was set at 0.05 and effect sizes were interpreted according to Hattie (2009); i.e., effect sizes with d = 0.4 and higher are classified as desired effects of educational interventions.

The results of the t-test show that playing the Escape Fake AR escape game was able to address the four learning objectives (overview in Table 2; Fig. 4):

The students significantly improved their knowledge about fake news, the effect size represents a desired effect of educational interventions; t(1, 27) = -7.08, p < 0.001, d = 1.34.

After playing the Escape Fake game, the students were significantly better at discerning the simulated social media postings, the effect size represents a desired effect of educational interventions; t(1, 27) = -2.06, p = 0.05, d = 0.39.

Further, the students were significantly more critical towards the trustworthiness of online information spread on social media after the intervention, the effect size represents a desired effect of educational interventions; t(1, 27) = -2.83, p < 0.01, d = 0.53.

Furthermore, playing the Escape Fake game significantly increased students’ confidence in being able to identify and verify false information in the future, the effect size represents a desired effect of educational interventions; t(1, 27) = -2.17, p < 0.05, d = 0.41.

4 Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of playing the AR escape game Escape Fake on learning objectives that are relevant in media literacy education. Based on previous literature, we tested the effectiveness of the game on four learning outcomes: Knowledge acquisition about fake news, information discernment ability, critical attitude toward online information, and confidence in recognizing fake news in the future.

As the result of this field study shows, playing the game significantly promotes the four learning objectives defined in this project with educationally relevant effect sizes.

Playing the game promoted students’ basic knowledge about the design and the motives of fake news as well as knowledge about tools how to check information; for example, by using the reverse image search. Further, after playing the game, students’ ability to discern real from false information significantly increased. According to Barzilai and Chinn (2020), developing knowledge and skills to evaluate information in the digital world is a meaningful aim of educational fake news interventions (also Apuke et al., 2022).

The results are in line with other studies finding positive effects of playful and game-based learning environments on learners’ discernment skills and reliability judgements (e.g. Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019a; Yang et al., 2021b). A unique value of the present study is that basic knowledge about fake news was also assessed; therefore, the study contributes to an extension of the empirical base on learning about fake news with games.

Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study presenting effects of an educational AR escape game about fake news. Other fake news interventions applying the escape game concept were tested as purely on-site implementations (Choi et al., 2017, 2020; Pun, 2017).

Also, the results of the study contribute to the still scarce empirical base on learning with escape games reported in systematic literature reviews (Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019; Makri et al., 2021; Veldkamp et al., 2020b). Similar to von Kotzebue et al. (2022) and Lopez-Pernas et al. (2019), we found positive effects of playing an escape game on knowledge and ability acquisition. Further, in this study, we revealed effect sizes comparable to the ones found in von Kotzebue et al. (2022) and Lopez-Pernas et al. (2019), indicating that the used escape games, according to Hattie (2009), are educationally relevant.

The results contrast other studies that found no effects (Cotner et al., 2018; Hou & Li, 2014) or even negative effects (Clauson et al., 2019) when learning with escape games.

We explain the effectiveness of Escape Fake with three main instructional elements integrated in the gameplay: First, Hannah Lee May, who serves as a pedagogical agent supporting learners during solving the puzzles. Research showed that pedagogical agents can enhance learning and when used as instructional guidance in games reduce the risk of cognitive overload (Wang et al., 2021; Westera, 2019). Thus, the presence of Hanna Lee May during the game makes Escape Fake a guided escape game reducing the risk of an increase of extraneous cognitive load. This is in line with CLT in which instructional scaffolds guiding learners during cognitively demanding learning environments are found to promote productive cognitive processing and to decrease unproductive cognitive load. As a results, the limited working memory capacity is not overloaded and, therefore, new knowledge can be transferred to long-term memory. This newly acquired knowledge can then be used to identify real from false news.

Second, the integrated multiple-choice tests allow students to reflect on the content of the game while the expiration of time pauses. Thus, Escape Fake overcomes the problem mentioned in Veldkamp, Knippels, et al. (2021b) of time pressure and too little time to reflect on content.

Third, the multiple-choice quizzes deliver basic knowledge about the design and the motives of fake news. Further, after choosing an answer, the players get immediate feedback, correct or incorrect, based on their decision. This makes the quizzes an effective learning activity discussed in the literature as test-enhanced learning. This instructional strategy proved to be effective for learning academic content with a medium effect size (Yang et al., 2021a).

Although the results for knowledge and ability acquisition are promising, it is important to point out that the effect of playing the escape game on the ability of information discernment is quite lower and only marginally educationally relevant compared to the effect on knowledge acquisition. This demonstrates that learning about fake news is complex and that knowledge about fake news alone cannot guarantee identifying false information. From an instructional perspective, we therefore recommend integrating the game in a well-planned and longer-lasting learning design as an additional educational resource to other instructional materials, courses, and games on the topic of fake news, which, for example, are described in the Debunking Handbook (Lewandowsky et al., 2020).

Further, a more critical examination of the effectiveness of escape games on skills acquisition is necessary. Both researchers and practitioners mention skills training as a main reason for using escape games. However, evidence for this assumption is lacking (Veldkamp et al., 2020). Although we found an effect of playing an escape game on ability acquisition, more research is needed to investigate how to improve ability facilitation when designing escape games for learning. For example, future research might consider prior knowledge and prior abilities as a possible influencing factor when learning with escape games. Such learner characteristics proved to impact learning in general, like found in research on CLT (Kalyuga et al., 2003), and when using escape games as a teaching aid (Eukel et al., 2017). In Eukel et al. (2017) only participants with high prior knowledge benefited from an escape game for learning about Diabetes.

Regarding the effects of Escape Fake on a more critical attitude towards the trustworthiness of online information, the result is in line with the assumption that educational escape games can address affective learning outcomes; like motivation (Queiruga-Dios et al., 2020), interest (Borrego et al., 2017), and sense of urgency (Ouariachi & Wim, 2020). Theoretically, the effect of Escape Fake on the attitudinal learning outcome can be explained by immersion experience. Immersion experience is defined as a deep cognitive and emotional involvement contributing to a strong identification with the protagonists of a game as well as with the game narrative (Georgiou & Kyza, 2017; Monaghan & Nicholson, 2017). In Escape Fake, the players experience from a first-person perspective the negative consequences of fake news published on the Internet. Consequently, the students in this study were emotionally involved leading to a process of rethinking regarding the trustworthiness of online information. This is in line with other researchers arguing that (escape) games can promote attitudinal change processes (Boyle et al., 2016; Veldkamp, Merx et al., 2021a).

Moreover, playing Escape Fake contributed to learners’ confidence in being able to detect fake news in the future. This result is in line with other studies showing that game-based learning environments promote confidence in one’s own abilities (Basol et al., 2020; Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2020). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that playing an (AR) escape game can advance this learning objective. The effect of Escape Fake on the confidence learning objective can be explained by the effective instructional strategies, according to CLT, applied in the game. These strategies supported students’ knowledge acquisition and information discernment ability resulting in higher confidence in one’s own abilities.

Additionally, this is the first study examining the effects of a playful fake news intervention assessing four learning objectives. However, learning to fight against fake news is complex (Barzilai & Chinn, 2020; Chinn et al., 2021); therefore, practitioners should not use the Escape Fake AR escape game as a stand-alone solution in their effort to prepare students for navigating the epistemic unfriendly online environments. As mentioned above, the game should be used as an additional educational resource in a longer-lasting instructional design on learning about fake news.

4.1 Limitations and Future Research

Although we examined the effect of an AR escape game on four learning objectives relevant in media literacy education on fighting fake news, further studies are necessary testing the effectiveness of the game on other learning outcomes; like the intention to share fake news with others (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2020). Additionally, we only assessed learning outcomes immediately after the intervention; thus, future research should conduct a study investigating possible long-term effects of the game; for example, like found in Maertens et al. (2021). To do so, researchers should assess the learning outcomes in follow-up tests; for instance, two or more weeks after using the game in the classroom.

Another limitation of the study is the emphasis on the role of knowledge and its application to stop the problematic spread of fake news. The issue of misinformation and disinformation is more complex and there are other factors to consider that are difficult to address through educational interventions. These include one’s own political views, personal convictions, and the sense of belonging to a group. Future studies could address this limitation by having multidisciplinary teams jointly develop and empirically test educational interventions (Kahan, 2013; Lazer et al., 2018). The factors mentioned could also be considered as possible influencing factors. For example, political views could be surveyed before playing in order to draw conclusions about their impact on the learning outcomes. In sum, results from such multidisciplinary studies can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of the game on learning about fake news.

Since this field study has shown that, in principle, learning happens when using the AR escape game Escape Fake, future research projects can examine how learning with the game might be even more effective. Therefore, researchers should work with control conditions modifying design elements of the game or other instructionally relevant aspects. For example, by using the value-subtracted research approach (Mayer, 2014), in the control condition Hannah Lee May supports the learners whereas in the experimental condition the players solve the puzzles without the help of the pedagogical agent. This research design can also be applied to other (AR) escape games developed by researchers and/or practitioners.

Another study, using the value-added research approach (Mayer, 2014, 2019), might investigate whether learning with Escape Fake (or other AR escape games) can be enhanced by adding effective learning strategies like summarizing or drawing (Fiorella & Mayer, 2016). For example, Pilegard and Mayer (2016) showed that combining an educational game with worksheets is more effective for learning then just playing the game.

As prior knowledge and prior abilities are important factors in learning with escape games (Buchner et al., 2022; Eukel et al., 2017), future research should also apply the learner-treatment interaction (LTI) research type to improve our understanding of how learner characteristics affect learning with escape games. This is especially important for AR-enriched learning environments, as LTI studies are lacking in the field of research on AR learning and instruction (Buchner & Kerres, 2023).

Further, future research should examine at what point of a learning design the use of Escape Fake works best. For example, Buchner et al. (2022) showed that providing learners with direct instruction before playing an escape game is more effective than providing direct instruction after playing. Furthermore, it would be interesting to examine if playing the Escape Fake game can serve as a motivational aid when used at the beginning of a longer-term fake news intervention study. It could be expected that playing the game raises students awareness for the problem of fake news and, therefore, contributes to higher engagement during the lessons on the topic. On the other hand, the escape game might also be used after a longer-lasting learning design on fake news to test if the design was effective. In this case, for instance, the multiple-choice quizzes integrated in the game serve as assessment of learning (Yang et al., 2021a).

Regarding the measurement of learning outcomes, in a future study an extension of the information discernment ability test is recommendable. For example, more and/or more difficult simulated social media postings can be used. Further, researchers could vary the design features of fake news applied to the postings. For example, it is possible that emotionalizing content is harder to differentiate than content that is more neutral.

Also, the knowledge acquisition test could be extended in future research projects.

Additionally, future studies should investigate the effectiveness of the game with a larger sample and should test the game with other school student populations. These methodological limitations require careful interpretation of the results without making claims of generalization.

A limitation for educational practice is the size of the markers. In a traditional classroom, using the DIN A4-sized images developed by Paraschivoiu et al. (2021) is difficult because students will have little space to move and to inspect the simulated rooms. Hence, future studies could develop solutions making it easier for teachers to use the game in the classroom, and easier for students to use the game at home, for example, in times of distance learning or as part of a blended learning scenario.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we provide evidence for the effectiveness of Escape Fake, an AR escape game, developed to be used in media literacy education. The game positively affects four learning outcomes: acquiring knowledge about fake news, fostering the ability to discern information, promoting a more critical attitude toward the trustworthiness of online information, and increasing confidence to recognize fake news in the future.

All materials needed to use Escape Fake in the classroom, e.g., marker images and the corresponding application, are available for free, making the game a valuable and accessible educational resource to prepare students to navigate the complex digital world.

Furthermore, since the game is also available in English, this study can be replicated by other researchers and the effectiveness of the game can be tested in other contexts and with different populations.

Future research is necessary to understand, how the AR escape game Escape Fake can be integrated in longer-lasting learning designs and how learning with the game can become even more effective.

Data Availability

Data used in this study is available online via https://osf.io/yagnr/

References

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social Media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Apuke, O. D., Omar, B., & Asude Tunca, E. (2022). Literacy concepts as an Intervention Strategy for Improving Fake News Knowledge, detection skills, and curtailing the tendency to share fake news in Nigeria. Child & Youth Services, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2021.2024758

Azuma, R., Baillot, Y., Behringer, R., Feiner, S., Julier, S., & MacIntyre, B. (2001). Recent advances in augmented reality. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 21(6), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1109/38.963459

Baron, R. J. (2019). Digital Literacy. In R. Hobbs & P. Mihailidis (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Media Literacy (1st ed.). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118978238

Barzilai, S., & Chinn, C. A. (2020). A review of educational responses to the post-truth condition: Four lenses on post-truth problems. Educational Psychologist, 55(3), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2020.1786388

Basol, M., Roozenbeek, J., & Van der Linden, S. (2020). Good News about Bad News: Gamified Inoculation boosts confidence and cognitive immunity against fake news. Journal of Cognition, 3(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.5334/joc.91

Bassford, M. L., Crisp, A., O’Sullivan, A., Bacon, J., & Fowler, M. (2016). CrashEd – a live immersive, learning experience embedding STEM subjects in a realistic, interactive crime scene. Research in Learning Technology, 24(1), 30089. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v24.30089

Borrego, C., Fernández, C., Blanes, I., & Robles, S. (2017). Room escape at class: Escape games activities to facilitate the motivation and learning in computer science. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 7(2), 162. https://doi.org/10.3926/jotse.247

Boyle, E. A., Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Gray, G., Earp, J., Ott, M., Lim, T., Ninaus, M., Ribeiro, C., & Pereira, J. (2016). An update to the systematic literature review of empirical evidence of the impacts and outcomes of computer games and serious games. Computers & Education, 94, 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.003

Buchner, J., & Höfler, E. (2024). Can pre-service teachers learn about fake news by playing an augmented realityescape game? Contemporary Educational Technology, 16(2), ep504. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/14335

Buchner, J., & Kerres, M. (2023). Media comparison studies dominate comparative research on augmented realityin education. Computers & Education, 195, 104711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104711

Buchner, J., Rüter, M., & Kerres, M. (2022). Learning with a digital escape room game: Before or after instruction? Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 17(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-022-00187-x

Chinn, C. A., Barzilai, S., & Duncan, R. G. (2021). Education for a Post-truth World: New directions for Research and Practice. Educational Researcher, 50(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20940683

Choi, D., An, J., Shah, C., & Singh, V. (2017). Examining information search behaviors in small physical space: An escape room study. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 54, 640–641. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2017.14505401098

Choi, D., Shah, C., & Singh, V. (2020). Investigating information seeking in physical and online environments with escape room and web search. Journal of Information Science, 016555152097228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551520972285

Clauson, A., Hahn, L., Frame, T., Hagan, A., Bynum, L. A., Thompson, M. E., & Kiningham, K. (2019). An innovative escape room activity to assess student readiness for advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs). Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 11(7), 723–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2019.03.011

Cooke, N. A. (2017). Posttruth, Truthiness, and alternative facts: Information behavior and critical information consumption for a New Age. The Library Quarterly, 87(3), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1086/692298

Cotner, S., Smith, K. M., Simpson, L., Burgess, D. S., & Cain, J. (2018). Incorporating an escape room Game Design in Infectious diseases instruction. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 5(suppl_1), S401–S401. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofy210.1145

Estudante, A., & Dietrich, N. (2020). Using augmented reality to stimulate students and diffuse escape game activities to larger audiences. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(5), 1368–1374. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00933

Eukel, H. N., Frenzel, J. E., & Cernusca, D. (2017). Educational Gaming for Pharmacy students – design and evaluation of a diabetes-themed escape room. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 81(7), 6265. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe8176265

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). Eight ways to promote Generative Learning. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 717–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9348-9

Fotaris, P., & Mastoras, T. (2019). Escape rooms for learning: A systematic review. Proceedings of the European Conference on Games-Based Learning, 235, 243. https://doi.org/10.34190/GBL.19.179

Franco, P. F., & DeLuca, D. A. (2019). Learning through action: Creating and implementing a strategy game to Foster innovative thinking in Higher Education. Simulation & Gaming, 50(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878118820892

Georgiou, Y., & Kyza, E. A. (2017). The development and validation of the ARI questionnaire: An instrument for measuring immersion in location-based augmented reality settings. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 98, 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2016.09.014

Georgiou, Y., & Kyza, E. A. (2018). Relations between student motivation, immersion and learning outcomes in location-based augmented reality settings. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.011

Glaser, N., & Moore, S. (2023). Redefining Immersive Technology Research: Beyond media comparisons to holistic learning approaches. Digital Psychology, 4(1S), 4–8. https://doi.org/10.24989/dp.v4i1S.2272

handysektor.de (2017). Fakt oder Fake: Das Handysektor Fake News Quiz. https://www.handysektor.de/artikel/fakt-oder-fake-das-handysektor-fake-news-quiz/

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis over 800 Meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Hermanns, M., Deal, B., Campbell, A. M., Hillhouse, S., Opella, J. B., Faigle, C., & Campbell, I. V., R. H (2017). Using an escape room toolbox approach to enhance pharmacology education. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 8(4), 89. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v8n4p89

Honebein, P. C., & Reigeluth, C. M. (2021). To prove or improve, that is the question: The resurgence of comparative, confounded research between 2010 and 2019. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(2), 465–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09988-1

Hou, H. T., & Li, M. C. (2014). Evaluating multiple aspects of a digital educational problem-solving-based adventure game. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.052

Illinois University Library (2020). Reverse Image Searching. https://guides.library.illinois.edu/c.php?g=347668&p=2344601

Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2021). Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other Literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869406

Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(4).

Kahne, J., & Bowyer, B. (2017). Educating for democracy in a partisan age: Confronting the challenges of motivated reasoning and misinformation. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216679817

Kalyuga, S., Ayres, P., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 23–31.

Khan, M. L., & Idris, I. K. (2019). Recognise misinformation and verify before sharing: A reasoned action and information literacy perspective. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(12), 1194–1212. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1578828

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal Guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

Klamma, R., Sous, D., Hensen, B., & Koren, I. (2020). Educational Escape Games for Mixed Reality. In C. Alario-Hoyos, M. J. Rodríguez-Triana, M. Scheffel, I. Arnedillo-Sánchez, & S. M. Dennerlein (Eds.), Addressing Global Challenges and Quality Education (Vol. 12315, pp. 437–442). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57717-9_41

Krüger, J. M., Buchholz, A., & Bodemer, D. (2019). Augmented Reality in Education: Three Unique Characteristics from a User’s Perspective. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computers in Education, 11.

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

Leiner, D. J. (2019). SoSci Survey (Version 3.1.06 [Computer software] [Computer software]. https://www.soscisurvey.de

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the Post-truth era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Ecker, U., Albarracín, D., Amazeen, M. A., Kendeou, P., Lombardi, D., Newman, E. J., Pennycook, G., Porter, E., Rand, D. G., Rapp, D. N., Reifler, J., Roozenbeek, J., Schmid, P., Seifert, C. M., Sinatra, G. M., Swire-Thompson, B., van der Linden, S., & Zaragoza, M. S. (2020). The Debunking Handbook 2020 [dataset]. https://doi.org/10.17910/B7.1182

Lopez-Pernas, S., Gordillo, A., Barra, E., & Quemada, J. (2019). Analyzing learning effectiveness and students’ perceptions of an Educational escape room in a Programming Course in Higher Education. Ieee Access : Practical Innovations, Open Solutions, 7, 184221–184234. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2960312

Maertens, R., Roozenbeek, J., Basol, M., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Long-term effectiveness of inoculation against misinformation: Three longitudinal experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 27(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000315

Makri, A., Vlachopoulos, D., & Martina, R. A. (2021). Digital Escape Rooms as Innovative Pedagogical Tools in Education: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(8), 4587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084587

Mayer, R. E. (2014). Computer games for Learning. An evidence-based Approach. MIT Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2019). Computer games in Education. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102744

Monaghan, S. R., & Nicholson, S. (2017). Bringing escape room concepts to Pathophysiology Case studies. HAPS Educator, 21(2), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.21692/haps.2017.015

Mulders, M. (2023). Confounding in Educational Research: An overview of Research Approaches investigating virtual and augmented reality. Digital Psychology, 4(1S), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.24989/dp.v4i1S.2227

Nee, R. C. (2019). Youthquakes in a post-truth era: Exploring Social Media News Use and Information Verification actions among global teens and young adults. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 74(2), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695818825215

Neumann, K. L., Alvarado-Albertorio, F., & Ramírez-Salgado, A. (2020). Online approaches for implementing a digital escape room with Preservice teachers. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 415–424.

Nicholson, S. (2015). Peeking behind the locked door: A survey of escape room facilitieshttp://scottnicholson.com/pubs/erfacwhite.pdf

Nicholson, S. (2018). Creating engaging escape rooms for the Classroom. Childhood Education, 94(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2018.1420363

Ouariachi, T., & Wim, E. J. L. (2020). Escape rooms as tools for climate change education: An exploration of initiatives. Environmental Education Research, 26(8), 1193–1206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1753659

Paas, F., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2020). Cognitive-load theory: Methods to manage Working Memory load in the learning of Complex tasks. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(4), 394–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420922183

Paraschivoiu, I., Buchner, J., Praxmarer, R., & Layer-Wagner, T. (2021). Escape the Fake: Development and Evaluation of an Augmented Reality Escape Room Game for Fighting Fake News. Extended Abstracts of the 2021 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 320–325. https://doi.org/10.1145/3450337.3483454

Pilegard, C., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). Improving academic learning from computer-based narrative games. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 44–45, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.12.002

Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., & Kinzer, C. K. (2015). Foundations of game-based learning. Educational Psychologist, 50(4), 258–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2015.1122533

Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., Mayer, R. E., & Kinzer, C. K. (2020). Theoretical foundations of Game-Based and playful learning. In J. L. Plass, R. E. Mayer, & B. D. Homer (Eds.), Handbook of game-based learning (pp. 3–24). MIT Press.

Polycular (2020). Escape Fake – Fight Fake News with a Game. https://escapefake.org/.

Pun, R. (2017). Hacking the Research Library: Wikipedia, Trump, and Information Literacy in the escape room at Fresno State. The Library Quarterly, 87(4), 330–336. https://doi.org/10.1086/693489

Queiruga-Dios, A., Santos Sánchez, M. J., Queiruga Dios, M., Gayoso Martínez, V., & Hernández Encinas, A. (2020). A virus infected your laptop. Let’s play an escape game. Mathematics, 8(2), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8020166

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2019a). Fake news game confers psychological resistance against online misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0279-9

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2019b). The fake news game: Actively inoculating against the risk of misinformation. Journal of Risk Research, 22(5), 570–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2018.1443491

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2020). Breaking Harmony Square: A game that inoculates against political misinformation. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-47

Scheibenzuber, C., Hofer, S., & Nistor, N. (2021). Designing for fake news literacy training: A problem-based undergraduate online-course. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106796

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J., & Paas, F. G. W. C. (2019). Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 years later. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 261–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09465-5

Traberg, C. S., Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2022). Psychological inoculation against misinformation: Current evidence and future directions. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 700(1), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162221087936

Tricot, A., & Sweller, J. (2014). Domain-specific knowledge and why Teaching generic skills does not work. Educational Psychology Review, 26(2), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9243-1

van der Linden, S. (2022). Misinformation: Susceptibility, spread, and interventions to immunize the public. Nature Medicine, 28(3), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01713-6

Veldkamp, A., Daemen, J., Teekens, S., Koelewijn, S., Knippels, M. P. J., & Joolingen, W. R. (2020a). Escape boxes: Bringing escape room experience into the classroom. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(4), 1220–1239. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12935

Veldkamp, A., van de Grint, L., Knippels, M. C. P. J., & van Joolingen, W. R. (2020b). Escape education: A systematic review on escape rooms in education. Educational Research Review, 31, 100364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100364

Veldkamp, A., Merx, S., & van Winden, J. (2021a). Educational escape rooms: Challenges in aligning game and education. Well Played a Journal on Video Games Value and Meaning, 109–135.

Veldkamp, A., Knippels, M. C. P. J., & van Joolingen, W. R. (2021b). Beyond the early adopters: Escape rooms in Science Education. Frontiers in Education, 6, 622860. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.622860

von Kotzebue, L., Zumbach, J., & Brandlmayr, A. (2022). Digital Escape Rooms as game-based learning environments: A study in Sex Education. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 6(2), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti6020008

Vraga, E. K., & Tully, M. (2021). News literacy, social media behaviors, and skepticism toward information on social media. Information Communication & Society, 24(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1637445

Wang, F., Li, W., & Zhao, T. (2021). Multimedia Learning with Animated Pedagogical Agents. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (3rd ed., pp. 450–460). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108894333.047

Westera, W. (2019). Why and how Serious games can become Far more effective: Accommodating Productive Learning experiences, Learner Motivation and the monitoring of learning gains. Educational Technology & Society, 22(1), 59–69.

Wild, F., Marshall, L., Bernard, J., White, E., & Twycross, J. (2021). UNBODY: A Poetry escape room in augmented reality. Information, 12(8), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12080295

World Health Organization (2020, May 11). How fake news about coronavirus became a second pandemic. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01409-2

Yang, C., Luo, L., Vadillo, M. A., Yu, R., & Shanks, D. R. (2021a). Testing (quizzing) boosts classroom learning: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(4), 399–435. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000309

Yang, S., Lee, J. W., Kim, H. J., Kang, M., Chong, E., & Kim, E. (2021b). Can an online educational game contribute to developing information literate citizens? Computers & Education, 161, 104057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104057

Zarocostas, J. (2020). How to fight an infodemic. The Lancet, 395(10225), 676. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Kerres and Prof. Dr. Jörg Zumbach for their support in planning and conducting this research project. Furthermore, I would like to thank Marc Lachmann and the dedicated colleagues who used the game in their teaching.

Funding

Open access funding provided by St.Gallen University of Teacher Education

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Participation in the study was approved by the school and was voluntary. Non-participation would not have had any negative consequences for the students. All students signed an informed consent form. Students were given a code that ensured anonymization of all data collected.

Conflict of Interest

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This research work was part of the authors’ doctoral thesis.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This study was conducted when the author was employed at the University of Duisburg-Essen, Learning Lab. Universitätstraße 2. 45,141 Essen, Germany.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buchner, J. Playing an Augmented Reality Escape Game Promotes Learning About Fake News. Tech Know Learn (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-024-09749-y

Accepted:

Published:

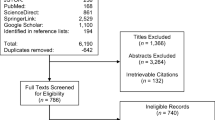

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-024-09749-y