Abstract

Digital technology is widely available in schools; however, results from international studies indicate that they are not effective toward students’ educational achievement. Teachers need to realise the potential of digital technology in their daily practises and use them well. However, teachers need training and guidelines to develop their expertise when using technology for teaching and learning. Failure to do so might result in students lacking the necessary coping skills for their future life in the information age. This literature review aimed to find out what factors affect primary teachers’ use of digital technology in their teaching practices, so as to suggest better training, which will eventually lead to a more guided and relevant use of technology in education. After applying the concept map to the data from the selected studies, four influencing factors were identified: teachers’ knowledge, attitudes and skills, which are also influenced by and influence the school culture. From these findings, recommendations on teacher training with technology and suggestions for further research are given.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The use of digital technology by teachers from early years in primary education makes learning a more familiar experience for students today. Using digital technology is also seen as the application of information and communication technology (ICT) by researchers and teachers in the field of education, where ICT is defined as “forms of technology that are used to transmit, process, store, create, display, share or exchange information by electronic means” (UNESCO 2007, p. 1). Consequently, teachers use digital resources to enhance learning by preparing lessons via powerpoint presentations and word document, or create communication channels for students and parents through social media and e-mails. Research has shown that teachers’ ability to use technology to plan and implement student-centred learning activities and effective communication with parents can enhance children’s learning (OECD 2010; Wake and Whittingham 2013; UNESCO 2011). Teachers’ use of digital technology is also recognized as important for children’s future employment and participation in society (European Parliament and the Council 2006; Leu et al. 2004; UNESCO 2011). However, although we are living in a technology-dominated society, the school might be the only place for some children to use digital technology since they have different family backgrounds and cultures (OECD 2010). Still, such technology savvy students must be appreciated and this requires new attitudes from the teachers such as to learn with and from the students, and further, to know how to facilitate learning with technology (UNESCO 2011; Wake and Whittingham 2013).

Nearly all teachers in europe use ICT to prepare lessons and in schools, its availability was for four out of five students (EU 2013). However, availability of digital technology and increased use by the teachers has not resulted in progress in relation to students’ educational achievement (OECD 2014). This shows that teachers need guided training on how to use digital technologies and take the right decisions especially when they change so quickly (Mishra and Koehler 2006). There are various differences among teachers, not only in their digital skills (Liang et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2011) and knowledge on ICT (Aesaert et al. 2013), but also on their attitudes towards the use of technology in their practise (Kim and Keller 2011; Lemon and Garvis 2016; Wake and Whittingham 2013; Wastiau et al. 2013).

2 Methodology

In this review, a synthesis of studies related to the use of digital technology was conducted to illustrate the factors affecting technology integration and to develop the definition of a digitally competent teacher. As of august 2016, the keywords “ICT”, “primary teacher” and “technology integration” were searched in three electronic databases: springer link, jstor and ebscohost since these are three of the most common academic databases (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/list_of_academic_databases_and_search_engines) which researchers use and were chosen to provide an over-view of the focus concerning teachers’ use of digital technology presented in this article. In total, the search generated 947 studies, the abstract, introduction and conclusion of each article were read. After eliminating duplicate studies, a total of 409 studies remained. The inclusion criteria for selecting the studies for this analysis were that (a) the subjects were pre-service or in-service teachers, (b) research included primary education, (c) it was an empirical research and (d) it was published in a peer-reviewed journal. After this procedure, 27 studies were selected as shown in Table 1, which served as the source of data for our analysis presented in this article.

2.1 Findings

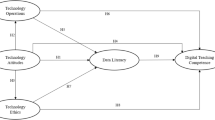

The review covered studies at primary school level, and included three methodologies; quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods. The percentage of quantitative studies was 40.8% where information was sourced from surveys. 37.0% were qualitative studies where data was collected from online communication, classroom observations, project based and inquiry learning activities, teachers’ reflections and evaluation on activities, interviews, one-to-one discussion meetings, focus groups and informal conversations. The mixed methods studies accounted for 22.2%. After reading the articles, a concept map was developed (Fig. 1) to categorize the factors which affect primary teachers’ use of digital technology.

A total of four main areas were identified including the school culture, teachers’ knowledge, attitude and skills. Descriptions of the results found in the studies, characteristics and classification are shown in Table 2.

2.2 School Culture

Teachers’ knowledge, attitudes and skills were both influenced by and influenced the school culture, since there was a reciprocal relationship between the school culture and the teacher. A school culture empowering quality teacher training allowed primary teachers to work collaboratively, reflect on the process and share the new knowledge (Hsu and Kuan 2013; Tondeur et al. 2016). It was suggested that in primary schools such learning opportunities must be provided for the teachers (Getenet et al. 2016). Working on local projects with digital technology, contributed towards teachers’ training and innovation (Tondeur et al. 2016) especially when adequate resources were available and feedback was provided during workshops on lesson design and teacher instruction (Getenet et al. 2016).

Furthermore, the school culture effected the teachers’ attitudes towards technology integration (Apeanti 2016). When the teachers were respected and valued for their work, they were motivated to use technology more often (Tondeur et al. 2016). Findings indicated that for a supportive school culture in primary education, digitally competent leaders, technical help and encouragement were required to integrate technology (Kim and Keller 2011; Omwenga and Nyabero 2016; Tezci 2011). Hsu and kuan (2013) found that the amount of time allocated to training and the teachers’ perceived support from the school, were the two most influential factors to technology integration. Further, when teachers collaborated and shared their projects more ideas were developed (Tondeur et al. 2016).

2.3 Teachers’ Knowledge

In the category of teachers’ knowledge, various areas such as teachers’ knowledge on themselves, on the students and on technology itself were identified. Teachers’ knowledge was related to what, how and why technology was used.

Knowledge on how to integrate technology in the classroom was reported by various researchers (Gu et al. 2013; Mishra and Koehler 2006; Orlando and Attard 2016). It was not enough to provide primary teachers with new technological tools; they also needed to know how to use them and the strategies for teaching purpose to meet the various needs of the students. For example, during digital story telling students were given the opportunity to safely share their stories, when using different digital approaches to express themselves (Duveskog et al. 2012).

Gu et al. (2013) found that there were differences between how teachers and students used technology and how they perceived its importance. Consequently, this knowledge could help teachers prepare more motivating lessons with adequate resources, considering also the affordances of multimodal activity that could be beneficial in reaching the digitally native students (Lenters and Winters 2013; Wake and Whittingham 2013). Besides, the new generation of teachers are themselves the digital natives, and could better understand and communicate with these students (Orlando and Attard 2016).

Mishra and Koehler (2006) further illustrated the teachers’ knowledge on the use of technology for the teaching purpose, in the technological, pedagogical and content knowledge (TPACK) framework, where effective technology integration occurs at the intersection area, of teachers’ technology knowledge (TK), pedagogy knowledge (PK) and content knowledge (CK). TPACK was not about developing expertise in individual technologies, but rather a mind set to help teachers plan effective technology integration, within the areas of technology, pedagogy and content (Dalton 2012). Research differentiated between knowledge on traditional curricula and curricula with technology; the latter were more complex and varied, and allowed for innovation in the subject content presented in the classroom (Aesaert et al. 2013).

It was found that one of the important factors to integrate technology was the teachers’ readiness to use it, when novice teachers experienced higher readiness than veterans (Inan and Lowther 2010). However, the use of technology was not influenced by the teachers’ age but by the number of years in service, where teachers with less than five years teaching experience, used technology less than those with longer service (Gu et al. 2013).

2.4 Teachers’ Attitude

Teachers’ attitudes toward the use of digital technology, in primary education were found to be related to teachers’ confidence, beliefs and self-efficacy, and with a significant relation to school culture.

Studies indicated that initially elementary teachers did not feel confident when teaching with technology and that their self-efficacy beliefs improved with time, when they observed and worked with their colleagues (Al-awidi and Alghazo 2012; Wake and Whittingham 2013). Technology was looked upon as a tool to help teachers deliver a better lesson, but with experience, it was considered for the educational development of the students (Wake and Whittingham 2013). Further training preservice teachers with explicit instructions, fostered positive changes in their beliefs and behaviours towards technology integration (Rehmat and Bailey 2014). Research on pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs could give insight on their confidence to integrate technology and allow for better pre-service teacher training (Lemon and Garvis 2016) while on the other hand effective technology training could contribute towards developing teachers’ positive attitudes and perceptions (Apeanti 2016). It was noted that novice primary teachers experienced device conflict since they were still learning how to use technology in their teaching practice (Orlando and Attard 2016) which indicated that they were not experts in technology integration (Wake and Whittingham 2013).

In a study conducted between two pre-service teachers’ cohorts in 2006 and 2012, barak (2014) found that teachers’ aptitudes towards the use of technology changed. In the first cohort, teachers depicted digital technologies as inefficient tools that weakened the teachers’ authority and brought about distractions in the classroom. On the other hand, the second teachers’ cohort indicated that digital technologies were beneficial to exploit teaching and learning experiences (Barak 2014). Consequently, in a recent study, primary school teachers showed great enthusiasm when using blogs to teach a foreign language (Al-Qallaf and Al-Mutairi 2016). It was observed that students were more motivated, worked independently and wrote longer sentences with fewer spelling and grammar mistakes (Al-Qallaf and Al-Mutairi 2016).

Generally, teachers’ attitudes and confidence in using technology did not depend only on its availability, as confident teachers exploited what technology was available for the benefits of the students (Wastiau et al. 2013). Teachers’ confidence and belief that technology was important for students’ learning were the main factors, which contributed towards technology integration, and also affected the students’ confidence to use it (Al-awidi and Alghazo 2012; Wastiau et al. 2013). However, Tezci (2011) concluded that having a computer and access to the internet were perceived by the teachers as influencing factors in enhancing the school culture towards technology integration.

2.5 Teachers’ Skills

Primary school teachers’ skills were mainly related to information management and visual literacy, to enhance their teaching practices. It was argued that teachers must consider multimodal activity for reading and writing activity (Wake and Whittingham 2013).

When using technology with fifth-grade students, teachers lacked the visual literacy (Wang et al. 2011) and the skill to choose the best information provided on the internet (Al-Qallaf and Al-Mutairi 2016). This was also evident after inquiring on sixth graders’ use of blogs, ms power point (ppt) and the internet; it was also found that students lacked the skills to assess information, take notes and synthesize the information (Al-qallaf and Al-mutairi 2016; Wang et al. 2011). Furthermore, in chile, Brun (2014) found that teachers only used a few digital resources mostly projectors and computers, where the ‘traditional’ teaching and learning methods were applied. Sun et al. (2014) stated that the way teachers interacted with the students, when giving instructions and asking questions with technology, influenced the students’ understanding of new concepts and encouraged more collaborative inquiry. It was suggested that in order to move away from the traditional ways of teaching and learning, teachers must apply inquiry activities, such as project based learning and problem based learning, which are more child-centred and constructivist in their approach (Tondeur et al. 2016).

The integration of technology challenged the teachers’ traditional methods of teaching and developed new skills such as applying the constructivist approach to teaching, learning, and orchestration, where the teacher fulfilled various roles and systematically organised different activities with technology, depending on students’ needs (Wake and Whittingham 2013). Nevertheless, teaching methods were noted to be evolving rather than in revolution with traditional teaching methods and depended on the type of digital technology being used (Orlando and Attard 2016). At primary level a distinction was noted between fixed and mobile technology, such as the interactive whiteboard (IWB) and ipads, where the former could be used with traditional ways of teaching, but the latter, due to their mobility required different classroom management and changes in teachers’ and students’ roles (Orlando and Attard 2016). Further, Anastasiades and Vitalaki (2011) found that teachers who daily-integrated digital technology in their practices found it easier to promote safety issues related to the internet by discussing the topic with the students.

3 Conclusion and Recommendations

Teachers found it difficult to adapt to new digital tools continuously, especially when previous lessons worked well, and to accept that some students might be more skilful in using a new digital technology than themselves (Morsink et al. 2010). Ultimately, it was found that preservice training in technology ensured better skilled teachers, with the right attitudes to develop digital technology in the school curriculum (Aesaert et al. 2013; Lemon and Garvis 2016).

This review of 27 articles is timely to highlight the importance of teachers’ professional development in the use of digital technology and how it can be sustainably developed during their school practices. As illustrated, teachers required not only the skill to use digital technology but also the right attitudes and the knowledge on how to apply these skills. It was revealed that the application of digital competence to primary school teacher’s professional development is in line with Ferrari (2013), where she indicated that for an effective use of digital technology, a citizen required digital competence (DC) which include the knowledge, the skills and the right attitude to use technology in five areas, namely to manage information, to communicate, to create content, for safety and to solve problems. Thus, like any other citizens, for effective use of technology, primary teachers need to apply such DC areas in their practices. These DC areas could be the indicators to measure the effective use of technology since analysing these areas could give evidence on how teachers are performing with technology. Table 3 illustrates the four factors affecting the teachers’ use of digital technology; the school culture, the teachers’ knowledge, attitudes and skills, which are cross-linked with the areas of DC.

Recommendations from the primary years’ teachers’ perspectives are discussed and suggested as guidelines for the teachers’ professional development in the sustainable use of digital technology in schools.

4 To Manage Information

When using digital technology, teachers need to know how to manage information. The right questions need to be asked and best sources of information searched, and then the data obtained is evaluated, synthesized and communicated to others (Leu et al. 2004). Teachers need to be able to teach their students how to search for information, which includes making use of various search engines and reading various articles, and then critically evaluate the results (Kinzer 2010). When teachers apply this strategy for information management in class, students learn how to think critically about information found on the internet. Research indicated that students lacked this skill (Wang et al. 2011) and it is the responsibility of the teacher to teach this area of DC. Knowing how to manage information will allow better life choices and safer social environment. In this digital environment, teacher training must consider multimodal ways of interacting with information since it had changed from print to multiple modes; including images, sound, video clips, text and kinaesthetic (Kress 2003; Lenters and Winters 2013; Wake and Whittingham 2013).

4.1 To Communicate

Studies indicated that the school culture was considered an important factor in technology integration, especially when the school management team offered encouragement and technical help to the teachers (Tondeur et al. 2016; Tezci 2011). When the teachers communicated and shared their teaching material, they felt confident and secure since their innovative approaches were accepted (Tondeur et al. 2016). Teachers felt their work was worthwhile when they were contributing to the local needs thus promoting a better school culture (Duveskog et al. 2012). Teachers should be encouraged to share their work to gain and give feedback and others can learn from their experiences. Various means can be used such as learning platforms, mobile phones and the internet.

In this review, various studies considered teachers’ communication and working together as a requirement for quality teacher training (Tondeur et al. 2016). Communicating with the students’ parents or guardians offers a great opportunity for teachers, to better design lessons tailored to students’ needs and activities initiated at school could be further discussed at home. This interest will foster more sharing between students’ different backgrounds and more inclusion especially where there is a language barrier. Teacher training in this DC area of communication could be useful since teachers can construct new knowledge, reflect on the process, give, and receive feedback. Through reflection, teachers could critically examine their work, understand new conceptions of constructivist teaching and learning, and accept new roles of teaching from an instructive to a more constructive approach (Brun (2014; Tondeur et al. 2016). In this environment, students can also provide feedback to their teachers and which is a learning opportunity (Wake and Whittingham 2013).

4.2 To Create New Content

Various studies mentioned the importance of creating and constructing new knowledge when using digital technology (Anastasiades and Vitalaki 2011; Sun et al. 2014). Further TPACK was considered a type of knowledge, which expert teachers applied when using technology, and involved the interplay of the three areas of technology, pedagogy and content knowledge. Developing teachers’ TPACK can result in creation and innovation in teaching and learning since technology changes how the teacher teaches and eventually the content as well (Mishra and Koehler 2006). Teacher training needs to acknowledge that content knowledge is always changing since information on the internet changes continuously and teachers need to adapt their pedagogical instruction. In this constructivist environment, the teacher is learning with students and develops the curriculum as she or he gains insight from the students (Duveskog et al. 2012; Tondeur et al. 2016). Teacher training on inquiry and pbl can be recommended for further teacher training in technology integration.

4.3 Safety

When using technology for teaching and learning, primary years’ teachers must be aware of legal frameworks to act ethically and responsibly. They can overcome concerns over internet safety when they are provided with the right information and given some ideas of how they can safely integrate technology (Anastasiades and Vitalaki 2011). The school management can filter unwanted websites, however if we want to protect the students from bad experiences on the internet, teachers must educate them. School management can organise talks with all those involved within the school community and make explicit the school’s ICT policies. Knowing these boundaries, everyone can use technology more confidently.

4.4 To Solve Problems

Evaluating and problem solving in a digital environment requires the teacher to recognize the difficulties related to a problem and subsequently assess the information to solve the problem and share the conclusions with others (Leu et al. 2004). Several studies indicated how teachers could make use of various digital activities to encourage problem solving; some of the mentioned activities were computer simulations, scenarios, blogs and inquiry activities (Al-Qallaf and Al-Mutairi 2016; Morsink et al. 2010; Tondeur et al. 2016). Training in this area is beneficial since students are already familiar with simulations through digital games and this could encourage learning. Training preservice teachers to solve problems with technology ensured better skilled teachers with the right attitudes to develop the curriculum later on in their profession (Al-Awidi and Alghazo 2012; Kim and Keller 2011; Wake and Whittingham 2013).

Since technology is continuously evolving, training with new tools must continuously be provided and this is quite challenging for the teachers, as they need to continuously adapt their teaching to new digital tools. Several studies in this review highlighted that teachers need the knowledge, the skills and the right attitudes to use technology (Barak 2014; Morsink et al. 2010). Teachers need to have the disposition to experiment with new technologies to capture the interests of all the students in the class (Kinzer 2010). This will result in more inquiry and innovation in learning (Sun et al. 2014). As stated by Dalton (2012) the teacher must reflect on his or her own strengths and interests, activities that she or he is already comfortable with and then develop the lessons with the use of digital technology. This requires time and collaborative training and feedback and a supportive school culture.

References

*Aesaert, K., Vanderlinde, R., Tondeur, J., & van Braak, J. (2013). The content of educational technology curricula: a cross-curricular state of the art. Education Technology Research and Development,61(1), 131–151.

*Al-Awidi, H. M., & Alghazo, I. M. (2012). The effect of student teaching experience on preservice elementary teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for technology integration in the UAE. Educational Technology Research and Development,60(5), 923–941.

*Al-Qallaf, C. L., & Al-Mutairi, A. S. F. (2016). Digital literacy and digital content supports learning. Electronic Library,34(3), 522–547.

*Anastasiades, P. S., & Vitalaki, E. (2011). Promoting Internet safety in Greek primary schools: The teacher’s role. Journal of Educational Technology & Society,14(2), 71–80.

*Apeanti, W. O. (2016). Contributing factors to pre-service mathematics teachers’ e-readiness for ICT integration. International Journal of Research in Education and Science (IJRES),2(1), 223–238.

*Barak, M. (2014). Closing the gap between attitudes and perceptions about ICT-enhanced learning among pre-service STEM teachers. Journal of Science Education and Technology,23(1), 1–14.

*Brun, M. (2014). Learning to become a teacher in the 21st century: ICT integration in initial teacher education in Chile. Journal of Educational Technology & Society,17(3), 222–238.

Dalton, B. (2012). Multimodal composition and the common core standards. The Reading Teacher,66(4), 333–339.

*Duveskog, M., Tedre, M., Sedano, C. I., & Sutinen, E. (2012). Life planning by digital storytelling in a primary school in rural Tanzania. Journal of Educational Technology & Society,15(4), 225–237.

European Parliament and the Council. (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and the Council of 18th December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning. Official Journal of the European Union, L394/310.

European Union. (2013). Survey of schools: ICT in education. Benchmarking access, use and attitudes to technology in Europe’s schools. Belgium: European Union.

Ferrari, A. (2013). DIGCOMP: A framework for developing and understanding digital competence in Europe. Seville: Joint Research Centre.

*Getenet, S. T., Beswick, K., & Callingham, R. (2016). Professionalizing in-service teachers’ focus on technological pedagogical and content knowledge. Education and Information Technology,21(1), 19–34.

*Gu, X., Zhu, Y., & Guo, X. (2013). Meeting the “digital natives”: Understanding the acceptance of technology in classrooms. Journal of Educational Technology & Society,16(1), 392–402.

*Hsu, S., & Kuan, P. (2013). The impact of multilevel factors on technology integration: The case of Taiwanese grade 1–9 teachers and schools. Educational Technology Research and Development,61(1), 25–50.

*Inan, F., & Lowther, D. (2010). Factors affecting technology integration in K-12 classrooms: A path model. Educational Technology Research and Development,58(2), 137–154.

*Kim, C., & Keller, J. (2011). Towards technology integration: The impact of motivational and volitional email messages. Educational Technology Research and Development,59(1), 91–111.

Kinzer, Ch. K. (2010). Considering literacy and policy in the context of digital environments. Language Arts, 88(1), 51–61.

Kress, C. (2003). Literacy in the New Media Age. London: Routledge.

*Lemon, N., & Garvis, S. (2016). Pre-service teacher self-efficacy in digital technology. Teachers and Teaching,22(3), 387–408.

*Lenters, K., & Winters, K. (2013). Fracturing writing spaces: Multimodal storytelling ignites process writing. The Reading Teacher,67(3), 227–237.

Leu, D. J., Jr., Kinzer, C. K., Coiro, J. L., & Cammack, D. W. (2004). Towards a theory of new literacies emerging from the Internet and other information and communication technologies. In R. B. Ruddell & N. J. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (5th ed., pp. 1570–1611). Newark, NJ: International Reading Association.

*Liang, L., Ebenezer, J., & Yost, D. (2010). Characteristics of pre-service teachers’ online discourse: The study of local streams. Journal of Science Education and Technology,19(1), 69–79.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record,108(6), 1017–1054.

*Morsink, P., Hagerman, M. S., Heintz, A., Boyer, D. M., Harris, B., Kereluik, K., et al. (2010). Professional development to support TPACK technology integration: The initial learning trajectories of thirteen fifth- and sixth-grade educators. The Journal of Education,191(2), 3–16.

OECD. (2010). Are the new millennium learners making the grade? Technology use and educational performance in PISA. Derby: Centre for Educational Research and Innovation.

OECD. (2014). PISA 2012 results in focus. What 15-year-olds know and what they can do with what they know. OECD: Paris.

*Omwenga, E., Nyabero, C., & Okioma. (2016). Assessing the influence of the PTTC Principal’s competency in ICT on the teachers’ integration of ICT in teaching Science in PTTCs in Nyanza Region, Kenya. 6(35).

*Orlando, J., & Attard, C. (2016). Digital natives come of age: the reality of today’s early career teachers using mobile devices to teach mathematics. Mathematics Education Research Journal,28(1), 107–121.

*Rehmat, A., & Bailey, J. (2014). Technology integration in a science classroom: Preservice teachers’ perceptions. Journal of Science Education and Technology,23(6), 744–755.

*Sun, D., Looi, C., & Xie, W. (2014). Collaborative inquiry with a web-based science learning environment: When teachers enact it differently. Journal of Educational Technology & Society,17(4), 390–403.

*Tezci, E. (2011). Turkish primary school teachers’ perceptions of school culture regarding ICT integration. Educational Technology Research and Development,59(3), 429–443.

*Tondeur, J., Forkosh-Baruch, A., Prestridge, S., Albion, P., & Edirisinghe, S. (2016). Responding to challenges in teacher professional development for ICT integration in education. Educational Technology & Society,19(3), 110–120.

UNESCO. (2007). The UNESCO ICT in Education Programme. Bangkok: UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2011). UNESCO ICT Competency Framework for Teachers. Paris: UNESCO.

*Wachira, P., & Keengwe, J. (2010). Technology integration barriers: Urban school mathematics teachers’ perspectives. Journal of Science Education and Technology,20(1), 17–25.

*Wake, D., & Whittingham, J. (2013). Teacher candidates’ perceptions of technology supported literacy practices. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education,13(3), 175–206.

*Wang, C., Ke, Y., Wu, J., & Hsu, W. (2011). Collaborative action research on technology integration for science learning. Journal of Science Education and Technology,21(1), 125–132.

*Wastiau, P., Blamire, R., Kearney, C., Quittre, V., Van de Gaer, E., & Monseur, C. (2013). The use of ICT in education: A survey of schools in Europe. European Journal of Education,48(1), 11–27.

References marked with an asterisk (*) indicate the articles used in the review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Spiteri, M., Chang Rundgren, SN. Literature Review on the Factors Affecting Primary Teachers’ Use of Digital Technology. Tech Know Learn 25, 115–128 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-018-9376-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-018-9376-x