Abstract

Through a lens for engaged scholarship (Boyer in Journal of Public Service and Outreach, 1(1), 11–20, 1996) this multiple case study (Merriam, 1996) explores the potential of scholarly podcasts for public knowledge dissemination, highlighting the misalignment of university impact metrics with this medium. Our team collected qualitative and numerical data from six podcasters across our university system. We identify metrics for assessing scholarly podcast value, offer recommendations for institutional communication, and share our insights and challenges. Data analysis suggests that a Listen Score (Listen Notes, ND) and an increasing Podcast Success Index (Singh et al. JMIR Medical Education, 2(2), 1–10, 2016) may be consistent with a wider reach. Consistent production and promotion are key and infrastructure support for scholarly podcasters is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Context

Scholars have begun to imagine uses of podcasts for the dissemination of public knowledge. A recent scoping literature review (Persohn & Branson, in review) about scholarly podcasting for public research dissemination found that podcasts are an economical way for researchers to share discoveries and provide listeners with a free and flexible learning experience (Kidd, 2012; Lim & Swenson, 2021; Loeb et al., 2023; Naff, 2020). Podcasts connect experts across regions, creating a virtual community of practice (Yuan et al., 2022; Diebold et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2020; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Naff, 2020; Thoma et al., 2018), and educate the public about specific topics by linking to disciplinary experts (Lim & Swenson, 2021; Naff, 2020; Nwosu et al., 2017). Podcasting can strengthen communication throughout a profession (Dong et al., 2020; Fronek et al., 2016; Naff, 2020; Nwosu et al., 2017) and support research dissemination which maximizes the potential of research usage (Naff, 2020). Podcasts also can serve as an entry point into specialized research conversation (Lim & Swenson, 2021; Singer, 2019; Thoma et al., 2018). In short, podcasting is an efficient, unifying, accessible, and multimodal means of communicating with an interested community (Dong et al., 2020; Lim & Swenson, 2021; Naff, 2020).

The conversational nature of podcasting “helps to reduce the potential for overusing research jargon” (Naff, 2020, p. 7). Conversations offer a humanizing experience of research that translates specialized research language and communication structures into a narrative (Cox et al., 2023; Diebold et al., 2020). Those who are listening to podcasts have the voices of podcasters quite literally “in their heads” through the highly individualized experience of listening in their own personal spaces, often using headphones (Singer, 2019). This type of audio experience and narrative format promotes connectedness and engagement with research ideas differently than traditional academic publications.

Podcasting allows for scholars to share academic work with the broader community in an open access platform that reaches audiences beyond those of academic journals. Podcasts may also allow scholars more academic freedom to express themselves compared to traditional modes of research dissemination (Cook, 2023; Hennig, 2017). Despite the proliferation of podcasts, the reach and impact of scholarly podcasts have not been well-studied (Wade Morris, 2021). Funding through an internal Interdisciplinary Research Grant allowed our research team the opportunity to study the phenomenon of scholarly podcasting by convening podcasters across one institution of higher education to analyze the impetus for, experiences of, and potential for the perceived value of our podcasting efforts. Specifically, our research aims to (1) identify salient metrics to communicate the value of scholarly podcasts, (2) provide recommendations for communicating the value of scholarly podcasting to our institutions, and (3) assess and communicate the opportunities, barriers, and lessons learned from producing podcasts to other scholars who may be interested in taking up the practice.

A core value of public universities is service to the public (APLU, 2023). However, university metrics for assessing impact value traditional academic publications, and therefore limit opportunities to freely share research findings with the public. Scholars in public institutions have a responsibility to make their research available and approachable for a broad public audience (Boyer, 1996). Our individual and collective work points to an inherent tension between the stated goals of public institutions and the possible "deleterious [impacts on] one’s career, tenure possibilities, and status among colleagues" (Semingson, et al., 2017) for engaging in public scholarship like scholarly podcasting. Therefore, for scholarly podcasting efforts to be widely supported by academic institutions, we must know more about the value of this work and how value may be communicated to multiple stakeholders. Therefore, our study addresses two research questions:

-

1.

What salient metrics can be used to communicate the value of scholarly podcasts?

-

2.

What are the opportunities, challenges, and lessons learned from producing scholarly podcasts?

Review of the Literature

What is Scholarly Podcasting?

Drawing from Singh et al. (2016), we define ‘scholarly podcasting’ as podcasts produced by faculty and staff through scholarly institutions. Cook (2023) notes that “for many scholars podcasting is an insurgency against academic structures that curb creativity, inhibit personal and collective transformations, and promote self-interest over generosity" (p. 1). Podcasts have been used by scholars to disseminate research findings to the public and to provide professional development opportunities for practitioners (Mobasheri & Costello, 2021). Dissemination of research via podcasting becomes possible with the ubiquity of smartphones (Mobasheri & Costello, 2021) – therefore podcasts are an accessible medium for both practitioners and learners (Danford et al., 2022).

Scholarly podcasts provide a dialogue shift within the academy – allowing presenters to connect with a broader audience (Kinkaid et al., 2020; MacGregor & Cooper, 2020). This can create community, highlight scholarly contributions, and communicate research findings, while allowing listeners to feel hopeful and optimistic (DeMarco, 2022; Mobasheri & Costello, 2021). In this way, podcasts remove the paywall of traditionally constructed epistemologies developed in the ivory tower – making academic knowledge more accessible to the public (Figueroa, 2022; Singer, 2019). In addition, podcasts can also be used to humanize learning that contributes to inclusive environments for students (Hennig, 2017; Moore, 2022; Page et al., 2020) because podcasts are flexible, portable, and accessible via the internet (Moore, 2022). As an outcome, podcasts allow for academic knowledge to be more readily translated to the public sphere.

Podcasting as a Form of Scholarship

Scholars (see e.g., Cook, 2023; Cox et al., 2023; Peoples & Tilley, 2011; Singer, 2019; Husain et al., 2020; Kinkaid et al., 2020; DeMarco, 2022; Figueroa, 2022; Copeland & McGregor, 2021) have argued for podcasting to be viewed as a legitimate form of scholarship. Some scholars (see e.g., Cabrera et al., 2018; Johng et al., 2021; Husain et al., 2020) have even argued for the use of digital scholarship (such as podcasting and other forms of social media) as part of academic tenure and promotion. Other scholars (see e.g., Cox et al., 2023; Copeland & McGregor, 2021; Williams, 2007; McNall et al., 2009; Boyer, 1990) envision a paradigm shift in what is considered “legitimate” or “valid” knowledge production (such as peer-reviewed journal articles) within the academy. This would enable a holistic approach that considers alternative scholarly contributions (e.g., blogs, podcasts, and instructional videos) in tandem with traditional metrics (e.g., peer-reviewed journal citations) (Cabrera et al., 2018).

When considering the affordances, possibilities, constraints, and obstacles of scholarly podcasting, it is important to distinguish between podcasts as a way to disseminate scholarship and podcasting itself as scholarship. It may be productive to consider podcasts as a vehicle for disseminating scholarship similarly to an edited work, particularly when a podcast features the work of selected scholars (Paulson et al., 2024; Stahl, personal communication, 2021). However, when a podcast is utilized to distribute one’s own work, it may be viewed more closely to self-publishing. The concept for and format of a podcast may be distinguishing factors when attempting to categorize podcasts within existing structures of academic publishing. Relatedly, podcasts with a guest/host interview format (like all podcasts included in this multiple case study) may necessitate different considerations from podcasts featuring the voice of the host only, which may be more closely related to a blog. Further complexifying the ways in which the value of scholarly podcasts may be viewed in the academic world, our team is aware of incidences wherein our podcasts have been cited in traditional research publications (e.g., Smith, 2023; Young et al., 2022). Research that examines the affordances and constraints of the scholarly podcasting medium to support the conveyance of ideas to the public constitutes its own field for scholarly study.

Recently, scholarly podcasts have been accepted for submissions to peer-reviewed journals (such as The British Columbian Quarterly) (Copeland & McGregor, 2021). However, there is no standard peer-reviewed protocol nor sufficient regulation of podcasts (Danford et al., 2022). In fact, the lack of peer review structures is argued as an affordance of the podcasting medium, as it allows for increased academic freedom and faster publication times (Cook, 2023). Cook’s point brings us to consider to whom the value of scholarly podcasts must be conveyed. While Cook (2023) provides multiple intrinsic motivations for scholarly podcasting as a form of public scholarship, most scholars are required to demonstrate the impact of their work to peers and institutional leaders.

A holistic approach to tenure and promotion (Sandmann & Weerts, 2008) evaluates faculty through a combination of peer review, impact, and expertise (O’Meara, 2015). Thus, a more definitive metric is needed to assess and convey impact of an individual's research in practice, teaching practices, and policy documents within the academy (Moore et al., 2018). These metrics may be particularly critical for scholars whose job responsibilities align with more traditional notions of how research shall be published. As Taylor et al. (2023) state, “many faculty members have avoided public scholarship since it is not rewarded by current promotion and tenure processes” (n.p.). They cite Ream et al. (2019) as explaining that “many faculty members also resist producing public scholarship out of fear for their own personal safety or job security, given the unpredictability of their audience, including members of academia within their own institution" (as cited in Taylor et al., 2023, n.p.). Moore et al. (2018) contend "dissemination" should be added to the “three-legged stool” of academia (e.g., research, teaching, and service). Although scholars (see e.g., Danford et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2016) have identified metrics used to assess the success of scholarly podcasts, these metrics have not been widely accepted or adopted in academia. As one entry point to understanding the value of scholarly podcasts, we first looked to metrics of value and impact already established in academia.

Bibliometrics and Altmetrics

Bibliometrics is a traditional measurement used to systematically quantify and analyze written communication (Bornmann, 2017; Broadus, 1987). These include the h index, total number of scholarly articles, journal impact factor, total number of citations, recency of publication, and altmetrics (Kenna et al., 2017). The impact of contemporary scholarship (including, peer-reviewed journals, podcasts, and blogs) is now more easily quantifiable through the number of views, downloads, geographic location (via IP address), Altmetrics, Social Media Index, DOI, likes, shares, among other figures (Husain et al., 2020). The problem with digital scholarship is that it is typically not peer-reviewed, and therefore considered ‘less scholarly’ (Husain et al., 2020). It is important here that we again make a distinction in scholarly podcasting that we will return to throughout our discussion: there are multiple forms of scholarly podcasting from programs wherein scholars share their views and opinions (like a blog) to those that invite other scholars to talk about their most recently peer-reviewed published works. Podcast metrics may need to be considered based on the podcast’s overall content and purposes.

Altmetrics (also known as “alternative academic products”) quantify impact on alternative forms of scholarship (Cabrera et al., 2018, p. 137). Altmetrics measurements are indicative of how scholarly information is being circulated outside of the academic sphere by identifying web-based interactions (Levin et al., 2023) such as social media engagement on Twitter, email, websites, blogs, and wikis (DeMarco, 2022; Galligan & Dyas-Correia, 2013; García-Villar, 2021; Gilstrap et al., 2023). The purpose of altmetrics is to measure the impact of scholarly contributions on public audiences (Williams, 2017). The benefit of using altmetrics is that it can be used to assess impact of academic dissemination at a more expedient rate than traditional metrics (Galligan & Dyas-Correia, 2013; Williams, 2017). The limitation of altmetrics is that the data can be easy to manipulate (García-Villar, 2021). The most widely used are Plum X and Altmetric.com (García-Villar, 2021). Plum X provides categorical metrics on the total number of captures, mentions, citations, usage, as well as social media reach (including, likes and shares) (García-Villar, 2021). Altmetric.com metrics are calculated based on author attribution, journal volume, number of times mentioned, and the source of the locations mentioned (Elmore, 2018; García-Villar, 2021).

Podcast Success Index

Specific to podcasting, the Podcast Success Index (PSI) was first developed by Singh et al. (2016) as an alternative and specific method to quantitatively valuate the success of a podcast. In their literature review, Singh et al. (2016) found that success of a podcast is determined by the number of episodes produced in a given month, total number of downloads or plays, duration of the podcast’s existence, and user ratings. However, they ultimately excluded the total number of downloads/plays and user ratings from the PSI equation because these data are not publicly available. Danford et al. (2022) also argue that user ratings may not be a valid metric for success because they are oftentimes skewed or biased. Therefore, one limitation of the PSI is that it draws from just two variables, total number of episodes produced and total number of months the podcast has been in existence. Danford et al. (2022) highlight that, because of the limited factors that go into the PSI formula, the PSI calculation may not reflect the overall success of a podcast. Singh et al’s, (2016) PSI research is also limited due to its focus only on podcasts in the field of anesthesiology. Even in light of these limitations, Danford et al. (2022) likens the PSI to a journal impact factor. These author teams conclude (and our team concurs) that more research is needed to develop and substantiate a uniform measurement of impact for podcasts.

Listen Score

Another metric used to quantify podcasting outcomes is the Listen Score. The Listen Score is available on the website ListenNotes.com as providing publicly available standardized quantitative scores to indicate the success or impact of a podcast. ListenNotes.com provides both a Listen Score and a global ranking among more than 3 million podcasts shared via RSS feed. According to ListenNotes.com, the proprietary Listen Score is "based on the 1st party data (e.g., activities on our website) and 3rd party data (e.g., media mentions, reviews, among others)" (ListenNotes, ND). It is considered “a relative metric” to assess the general popularity of a podcast. However, Listen Scores are only generated if the podcast ranks among the top 10% of podcasts produced globally among the more than 3.1 million podcasts that the site tracks. Listen Scores are updated monthly.

Conceptual Framework

Ernest Boyer’s (1996) definition and model of engaged scholarship serve as a framework to inform our thinking. Boyer’s (1996) model, laid out in one of his final and most influential works ‘The Scholarship of Engagement’, provides a theoretical map for scholars and experts to reconsider how they engage with the public. Boyer shares four interrelated dimensions of publicly-engaged scholarship: discovery or pursuit of new knowledge, integration or interdisciplinary connections, application of knowledge and “doing good” with that knowledge, and teaching or the communal act of sharing that knowledge. While Boyer’s ideas preceded the development of many of the digital platforms available to scholars today, conceptually, his ideas offer many possibilities in contemporary times. To this point, while Boyer uses the term engaged scholarship, other scholars use a variety of terms to name particular ways in which scholars may engage with a public audience. Public scholarship is an umbrella term for translating and communicating research for a non-academic audience, to advocate for or initiate change (Monk et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2023). Singer (2019) uses the term social scholarship, or the use of social media to engage in and expand the scholarship of discovery, integration, teaching, and application (Greenhow & Gleason, 2014), and addresses podcasting specifically as a form of social scholarship. Scholars and disciplinary experts are finding new ways of sharing knowledge and exchanging ideas in online public spaces, honoring Boyer’s intent of scholarship that reaches a wide audience, with the ultimate goal of “doing good” (Persohn & Branson, in review). We employ Boyer’s framework as a way to understand our scholarly podcasting as public scholarship. We see our podcasts as supporting our university to meet goals of broadly engaging the public in research and knowledge dissemination. In order to speak to those institutional goals, we must better understand the value of scholarly podcasting.

Data Sources and Research Methods

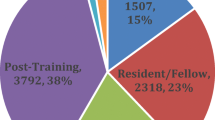

For this research, we employed a multiple case study approach (Merriam, 1996) as both the process of conducting a case study as well as the unit of study for the case itself. Each member of our transdisciplinary team is involved in a different podcast series with differing purposes, production logistics, and resources. Specifically, we draw upon a multiple case study approach (Merriam, 1996) to track and analyze our podcasts’ data. Each team member holds a different position at the University of South Florida (USF) and varying roles in scholarly podcasting. We are hosts, co-hosts, and/or producers of the podcasts known as Calling Earth, Classroom Caffeine, Faculty on Tap, Frontline Nursing, Inside USF, and Trailblazing Nursing. Although each podcast’s objectives differ (see Table 1), one overarching goal is to build community and discourse around specific topic areas (e.g., nursing, education, library sciences, and university communications).

Each of the six podcasts included in our study constitutes its own bounded case with unique objectives, structures, and procedures that drive the podcast content, production, and promotion. These podcasts have been established by faculty and staff within one university system across the last one to four years. The podcasts represent topics across natural sciences, social sciences, and university communications. Table 2 provides particularistic, descriptive, and heuristic features of each podcast or “case” included in our interdisciplinary multiple case study. Our research team was interested in “insight, discovery, and interpretation” (Merriam, 1996, p. 29) related to the phenomenon of podcasting by and through institutions of higher education pertaining to our research questions.

Utilizing Merriam’s framework for case study analysis afforded our team opportunities to move between qualitative and numerical “bits of data,” making sense of data through conversation and exploration of concepts related to the data as we collected it (Merriam, 1996, p. 178). Together, multiple cases in our study and team members from a variety of fields provided us opportunity to suggest generalizations about scholarly podcasting as well as contrasting ways to enhance and question those generalizations.

Data Collection

We developed a survey to collect monthly data related to the number of episodes published, total downloads, geographic reach, most popular episodes, number of subscribers, social media sharing practices, listener ratings and reviews received, top platform, website traffic (if applicable), and any known citations of the work. While we aimed to collect a wide range of information in order to make sense of our cases individually and collectively, we quickly learned not all members of the research team had easy access to every data point. These data proved most useful in evaluating each podcast across cases to better understand connections between and among the data points. We used these data to help us contextualize, support, and/or counter existing standardized measures of podcast success such as the PSI and Listen Scores in relation to the mission of each podcast.

Additionally, we collected qualitative survey data around opportunities and challenges of academic podcasting from each of our team members. These data stemmed from observations of our own experiences, anecdotal evidence from conversations in our collegial circles, and contextualizing experiences with our own podcasts. Specifically, we collected responses to questions about how we produce our podcasts, identify and connect with our target audience, promote our podcast, communicate the impact or success, definitions of impact or success, and support the longevity of our podcast. We compiled these observations and reflections for each podcast represented by our team, and then looked across cases to produce a synthesized list of considerations and suggestions for dissemination to other scholarly podcasters.

Limitations

One limitation of our data set is that, while we all hold different job titles and responsibilities, all podcasters on our research team are homed at one academic institution. While we represent campuses and entities across our entire university system, this fact may limit our potential for identifying opportunities and challenges that exist outside of our own environment. Through our data collection process, we also learned our various podcasting hosting sites did not all offer the same data points. Our results are based on the most complete and accurate data we were able to access. Another potential limitation of our interpretations is the scant published literature available to support interpretations of the PSI (Danford et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2016) and Listen Score.

Multiple Case Study Data and Analysis

Podcast Metrics

During our initial analysis, the research team members often cited downloads as a way of conveying the impact of a podcast. The number of downloads points to the number of times a podcast has been heard, as a potential indicator of the number of people a podcast has reached. Download data is not publicly accessible but easily accessed by a podcast’s producer, typically through the show’s hosting site. We collected this data for six consecutive months. Figure 1 provides a snapshot of the total number of downloads reached at the beginning, midpoint, and end of our data collection period. These data indicate that consistent production of podcasts leads to an increased rate of downloads. Classroom Caffeine and Inside USF, for example, are the only shows that have been actively produced for the entirety of our data collection. Calling Earth, Faculty on Tap, Frontline Nursing, and Trailblazing Nursing have plateaued in the total number of downloads garnered.

In addition to downloads, we collected data on the total number of countries and territories where each podcast has been downloaded (see Fig. 2). These metrics were important to our team members because geographic reach speaks to the global impact of our collective work. Similarly to downloads, we identified a potential relationship between increased geographic reach and consistent, active production for some podcasts. Classroom Caffeine, for example, consistently grew in the total number of countries and territories reached. The show’s target audience is teachers and others working in the field of education, a relatively large niche audience. The host also interviews guests from outside the U.S. which has helped the show’s reach on a global scale, as guests share their episode with their own circle of influence. Trailblazing Nursing continued to grow in geographic reach until production halted in early 2023. The total number of countries and territories reached plateaued when production halted. Inside USF, on the other hand, did not increase in geographic reach despite having consistent and active production. This may be due to the show’s narrow focus on university communications and niche target audience (much unlike Classroom Caffeine and Trailblazing Nursing). Therefore, geographic reach may be a less significant measure of success for niche podcasts.

Podcast Success Index

Since one goal of our research is to move beyond our team members’ typical or colloquial ways of assessing podcast success, we utilized quantitative instruments to measure podcast success. Table 3 shows the PSI for each podcast in our study calculated using Singh et al.’s (2016) logarithm (PSI = log [(episodes/month) √months active]) at the beginning, midpoint, and end of our data collection period.

Across our data, in addition to consistent production leading to a relatively high PSI (an anticipated outcome based on the PSI formula), we see a possible relationship between a higher PSI and greater number of downloads. The Huberman Lab (a popular neuroscience and wellness podcast hosted by Dr. Andrew Huberman of Stanford University’s School of Medicine) provides a comparison point to our PSI calculations in Table 3. We use this specific podcast as an example of success because it has been producing content for over three years and is hosted by a faculty member from a renowned institution. As of January 2024, the Huberman Lab podcast has garnered a PSI of 1.50 (PSI = log [(189/35) √35]). While we have no access to download data for the Huberman Lab podcast, we reason that with more than 500,000 subscribers to Dr. Huberman’s daily email newsletter as cited on the show’s website, the show would garner a large number of downloads for their weekly podcast release.

We reason that consistent production provides for automatic downloads from subscribers, therefore increasing the number of downloads for a podcast. So, while the PSI calculation does not include the number of downloads, there may be some inherent relationship between the number of episodes produced and the number of downloads a podcast garners. Downloads may also continue to grow if the podcast is still available to listeners, though our data suggests the rate of growth slows or becomes stagnant once a podcast is no longer in active production. Singh, et al. (2016) identify podcast downloads as a salient factor connected with the success of a podcast but exclude downloads from their calculation because these data are not publicly available. These comparative data lead us to question the overall validity of the PSI, particularly for podcasts that are either extremely popular or with very few episodes produced.

Singh et al. (2016) identify listener ratings as a potential indicator of podcast value. However, they note that listeners infrequently leave numerical ratings or qualitative reviews. In most cases, we were unable to access the full extent of data relating to the ratings and reviews of our respective shows. This was because some data was difficult to track, particularly ratings and reviews for shows where the host or producer did not have full access to the show’s data or when the most popular podcast hosting platform for a show changed from month-to-month. Small numbers of ratings appear to skew rating factors outside of the podcast content or production value. We find that qualitative listener reviews may support a more robust picture of podcast success and impact. But there are limits to these data, especially with a small sample of reviews because neutral parties do not typically leave ratings; it is either the best or the worst (Ghose & Ipeirotis, 2006). Due to the limitations of ratings and reviews, combined with the fact that these data are only publicly available through individual podcast platforms (e.g., Apple Podcasts, Spotify, etc.), Singh et al. (2016) did not include these data in their calculation. Therefore, these data may not always provide helpful contextual information to assess a podcast’s success.

Listen Score

We also identified the Listen Score as a standardized measure of podcast success. A ListenScore (ListenNotes, ND) is obtained from an online aggregator database and provides a publicly available score to indicate the success or impact of a podcast. Podcasts only register with a ListenScore if they are among the top 10% of all podcasts that are distributed through RSS feeds. Therefore, not every podcast will have a ListenScore.

Table 4 contains the Listen Scores retrieved during the last month of data collection and the Global Rank for our podcasts. Our data suggests consistent production over time and a broad target audience may increase the likelihood of obtaining a Listen Score. Over the course of our data collection period, the three podcasts with the highest PSIs have garnered a Listen Score. As an example for comparison purposes, the Huberman Lab podcast (mentioned previously in the discussion of the PSI) has a Listen Score of 82 and it is considered one of the top 0.01% of all podcasts. While Inside USF does not currently have a Listen Score, at one time it registered a score and a global rank. Presumably, growth of other podcasts in the top 10% has shifted Inside USF out of the range of a Listen Score and Global Rank. While Inside USF and Calling Earth have similar PSIs, we can account for their difference in Listen Scores because Calling Earth has been in existence for over four years, more than twice as long as Inside USF. Across our data collection period, Classroom Caffeine has consistently registered a Listen Score. Classroom Caffeine has been in consistent and active production for more than two and a half years.

In addition, we collected data on the top three most downloaded episodes each month to evaluate trends related to the popularity of episodes. Typically, this did not change from month to month. So, it was less important in our analysis.

Qualitative Survey Data

To answer our second research question, we gathered qualitative data through a monthly survey to enrich and contextualize our cases. Because our podcasts represent several fields within higher education, target different audiences, and operate under varying structures, it became important to understand more fully why some podcasts in our study continued to grow while momentum for others waned. Each member of the team involved in the production of a podcast completed a survey designed to capture details of the opportunities and challenges for each show. Specifically, the survey questions asked about:

-

the challenges, limitations, and opportunities around the concept of each show, the logistics of producing each show, and connecting with the target audience or promoting the podcast,

-

ways in which the producer communicates the show’s success and impact,

-

future goals for the podcast and resources needed to reach those goals,

-

advice for future podcasters, and

-

surprises in producing an academic podcast.

The following section represents a summary of reports provided by the hosts and/or producers of our case podcasts. While all hosts/producers focused on continuous quality improvement of the production or dissemination of their work, each offered unique reflections on their opportunities and challenges.

Opportunities and Challenges for Each Scholarly Podcast

Calling Earth

The primary challenges for Calling Earth are related to issues with logistics and production. The podcast began by focusing on interviews with faculty in the Geosciences, a potential guest list that is largely exhausted. Next steps include expanding to related fields, such as Marine Science and other departments. This will allow for assistance in moving the focus from just one academic area to a broader but still cohesive field for interview subjects. Another significant challenge is working alone on the podcast. The host plans to gain more self-sufficiency with the editing and production process. The host is also looking to identify new project collaborators to support concept development. One additional challenge has been how and where to market the show on social media. For the future, the host plans to implement social media and/or website strategies to reach a broader audience and is seeking marketing support.

Classroom Caffeine

The primary challenge for Classroom Caffeine has been the lack of formal training in social media marketing in tandem with the amount of time necessary to produce the podcast (such as planning, recording, and producing each episode, and managing the podcast’s website). Producing the podcast has provided the host unanticipated opportunities to expand her professional network by connecting with other scholars across the U.S. and around the world. The show has garnered interest from other scholars requesting to be a guest on the show, providing opportunities to build new connections. Although editing the show oneself can be time consuming, this has allowed the host to control the “feel” of the show. Because of the workload, the host now produces one episode a month rather than once every two weeks for the current season, which will potentially have a negative impact on the PSI and Listen Score. To improve the podcast’s reach, the host has enlisted a research assistant to develop digital marketing for social media. This helped increase the podcast’s downloads and website hits. For the future, the host will employ a student from Marketing to further develop promotional strategies.

Faculty on Tap

The primary challenge for Faculty on Tap has been largely due to logistical limitations and personnel changes. Originally, the podcast was to collaborate with the Brewing Arts program at our university to host the podcast at local breweries. Restrictions with the COVID-19 pandemic in tandem with the amount of time it takes to create the podcast have decreased production activity. With pandemic restrictions lifted, the hosts plan to record in local breweries using small portable technology. The show has also experienced technical issues with production and support due to staff turnover. This has forced the other hosts to learn how to mix audio for the podcast. The Faculty on Tap team has identified a way to broaden the scope of the show by highlighting faculty across all three university campuses. Although adopting the strategy of featuring faculty across campuses would entail altering the original purpose of the podcast, it would allow the show to reach a broader audience.

Frontline Nursing

The primary challenge for Frontline Nursing has been the workload associated with the production of each episode and redefining the podcast’s objective. Regular podcast production took much more time and effort than anticipated by the host/producer. The original objective of the podcast was to promote knowledge and skills for nurses to stay safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. As we move toward a post-pandemic era, the podcast’s objective will need to be redefined. The host plans to reestablish a steady production timeline and focus on reward, recognition, and renewal activities for nurses.

Inside USF

The primary challenges for Inside USF are due to changes in the show’s concept, a limited potential audience, and shifts in the production schedule. The show’s concept originally featured guests from a variety of positions and rankings in the university community. In the second season, the focus has shifted to leaders within the university. The number of listeners decreased by nearly half from season one to two. To address this issue, the host hopes to return to the original concept of the podcast, which was to enhance communication and build internal brand champions among faculty and staff. By broadening the topics and guests on the show, the host aims to promote the university to the public. The podcast has also experienced changes with logistics of recording the show, moving from contracted services with the campus radio station for production in the first season to acquiring their own equipment to produce the show in its second season. Working with the radio station created significant limitations for scheduling because of the station's other programming obligations. This shift has eliminated scheduling constraints and reduced unnecessary costs.

Trailblazing Nursing

The primary challenge for Trailblazing Nursing has been finding guests to interview. This is largely due to the show's sole focus on nursing experts, and therefore excludes other disciplines within health care. Because of this, the producer plans to attract new listeners by creating podcast episodes or seasons based on themes and concepts (such as female empowerment). The themes and concepts will transcend the nursing discipline and create valuable discussions that offer professional development to nurses. With the investment in new recording equipment, the producer has been able to improve the sound quality and reach of the show.

Cross-Case Analysis

We found that the presence of a Listen Score and a relatively high or comparatively increasing PSI value may be consistent with an increased rate of the total number of downloads, and in some cases, a greater geographic reach. Although there is relational evidence, these metrics must be considered with caution. Calling Earth, for example, has a Listen Score but is currently idle. This podcast, however, has produced episodes for over three years, which may be a longer lifespan than many podcasts experience. While there is no definitive average life of a podcast, there is evidence that scientific podcasts typically do not last beyond two years (DeMarco, 2022). Additionally, a podcast that is still producing but moves to a longer production timeline, would see a decrease in the PSI, even though the show may still be gaining listeners and reaching a broader audience.

In looking across the input from our team members, we note that not having enough time and working alone most often hindered consistent podcast production. Some of us lost team members and/or co-hosts due to turnover or competing job responsibilities. Others found difficulty clarifying objectives of our podcasts, particularly if the podcast was founded in response to a specific challenge (such as in the case for Frontline Nursing). Additionally, no one on our research team received formal training in skills to edit and mix audio. We conclude that no formal training in podcast production has slowed our ability to produce consistent content. Inside USF, for example, is supported by University Communications and Marketing at our university. This partnership essentially allows the host to prioritize consistency of the show’s production.

Another layer of challenges existed when a few podcasters struggled to reach a target population of listeners. In some cases, podcasters who showcased niche topics or catered to specific audiences have found it challenging to grow their listener base. A few members of our research team had issues with identifying new guests to interview or new lines of inquiry to pursue. In addition to the time it takes to record, edit, and set an episode for release, planning ahead to maintain momentum and promoting the show to new audiences are all steps that take sustained time and effort. As one case example of how these factors of success may impact each other, Classroom Caffeine has been successful in reaching a broad global audience due to support from research assistants through internal grant funding. Research assistant support has provided the human capital necessary to create and maintain an active social media and website presence for the show. This show also uses remote technology to conduct interviews (e.g., Zoom calls), which has allowed the host greater access to guests living in other global regions. Featuring international guests has also provided exposure to international listeners for the show.

Discussion

In this study, we set out to learn what salient metrics may be useful in communicating the value of scholarly podcasts and to identify opportunities, challenges, and lessons learned from members of our research team’s experiences producing scholarly podcasts.

Our findings suggest that PSI values and Listen Scores must be evaluated with contextual factors related to the show’s production. While the PSI may be helpful in measuring the success of a podcast, it may be less effective as a means of communicating podcast success because the PSI is not widely known or understood. Additionally, we would caution the use of the PSI for measuring or communicating the success of shows no longer in active production or those that are extremely popular, such as The Huberman Lab podcast. An area for future research with the PSI might calculate PSIs for a wide range of podcasts to determine whether the index is a valid measure for shows at extreme ends of the rankings distribution. A Listen Score will only be applicable for podcasts within the top 10% of all podcasts globally. Listen Scores are based on an unknown proprietary calculation. Therefore, a Listen Score may not be available for all scholarly podcasters looking to measure or communicate the value of their work.

While a relatively high PSI and/or the availability of a ListenScore should communicate a level of success and impact for the podcast, any successes are likely to carry different weight for the podcast producer. For podcast producers and hosts, an individual’s specific job responsibilities as well as institutional views on what tangible outputs are important to the job are likely to influence how these metrics are perceived by peers and leaders. The priorities embedded in one’s job description as well the mission of the podcast are likely to influence what factors of success are most valued. With Boyer’s (1996) call to action for academic institutions highlighting the critical nature of communicating research to the public for the ultimate purposes of research utilization, our diverse team of both university faculty and staff is left wondering whose job it is to do the work of public scholarship. While our study indicates there may be ways to more universally measure and communicate podcast success, how might those values be perceived differently in light of different job responsibilities? Based on our own experiences, we reason that perceived value is partially in the way one is able to tie podcasting into the narratives of their unique job responsibilities. When scholarly podcasting can be more closely associated with one’s goals and overall trajectory, those in supervisory positions of power may have a higher perception of the value of podcasting work. In our experiences, we find that when research around scholarly podcasting and public knowledge dissemination is aligned with one’s research focus, podcasting work may be perceived as having greater value to institutional stakeholders.

One less concrete outcome of scholarly podcasting is that the practice can be used to build social networks within one’s own discipline and by connecting to the public as well as the university community. For example, if a podcast host interviews experts in their field of focus for the show, new professional connections can be made and new listeners may tune in based on the guest’s notoriety and networks. These connections may promote the work associated with the host’s institution. While professional connections may be challenging to measure, this type of networking across our fields may help to meet institutional goals related to the development of a more universal knowledge economy.

Some cases in our study found difficulty with promoting our shows through social media, from identifying appropriate platforms for target audiences to creating suitable promotional tactics and content for podcasts. Social media provides a way for scholars to engage listeners with their podcast (Copeland & McGregor, 2021). Social media promotion and digital marketing, however, can be a fulltime job, requiring expertise and extensive training. Our findings suggest the lack of formal training in how to engage with the public has further challenged members of this research team in reaching a broader audience. Promoting a podcast becomes more feasible when knowledge dissemination and/or public communication is a part of a podcasters’ job responsibilities (e.g., Classroom Caffeine, Inside USF). One additional way to gain listeners is to embed podcast episodes in courses preparing individuals to enter professions, such as courses for college credit (e.g., Classroom Caffeine). Embedding podcasts as course content requires professional networking in addition to holding content relevant to course topics. In short, we found promotion may connect a podcast with listeners across broad geographic areas, increasing both the number of downloads and reach. Much of the success of a podcast is dependent upon the show's objectives, purposes, format, production value, promotional techniques, the presence of a website, and the overall strategic investment and expertise of the producing individual or team to sustain this work.

Taken together, our quantitative and observational findings suggest that consistent and active production and promotion is necessary to reach a broader audience. Our podcasts are intended to provide discipline-specific audiences with information from experts in an accessible format by engaging new listeners with the content and retaining the current audience. To make this possible, we argue that scholars will need infrastructure to do this work, specifically in the form of recording space/equipment, production support, and/or promotional support. Producing a podcast also requires financial support for logistical matters (e.g., recording hardware, editing software, a podcast hosting platform, a website host platform, web domain, and other technologies). Of course, this type of monetary investment in equipment and software or subscription services is necessary up front and on an ongoing basis. Ongoing time and attention commitments are also necessary to see a podcast program thrive. Our study found that having open-ended research questions, topics, and objectives, in tandem with consistent digital marketing may be associated with having an increased rate of downloads. Human capital is also required to do the work of program planning, recording, production, and promotion. Even when one’s job responsibilities include dissemination of scholarly ideas, this work is only possible long term with the help of a supportive team.

Our research study demonstrates that inconsistent financial and personnel support ultimately hindered the production of podcasts. It is challenging to sustain energy and focus when scholarly podcasting is on the periphery of a person's responsibilities. Recent literature suggests that institutional support is needed to improve the longevity of a scholarly podcast (Cook, 2023; Cox et al., 2023). Sources of funding may include grants, philanthropic donations, and newer models of financial support from listeners such as subscriptions and “tip jar” approaches to sustainability for production. We encourage innovation in identifying funding streams, while ensuring the altruistic nature of scholarly podcasting is taken into consideration. Obtaining external funding for podcast production and/or research on the work of a scholarly podcast may be a boon for how the work is viewed by institutions.

Valid and reliable methods of valuating scholarly podcast production are useful for consideration in the academic promotion and tenure processes. While the PSI and Listen Score may be utilized in review materials, in our experience, peer evaluators and academic leaders tend to be most interested in the number of downloads for a podcast. The high number of downloads (particularly compared with the numbers associated with traditional publications) combined with broad geographic reach may be highlighted as a pride point in success metrics. Scholars have argued for a need to institutionalize and legitimize podcasting as a scholarly mode of dissemination (Copeland & McGregor, 2021). McGregor and colleagues have made significant progress in this area by establishing the Amplify Podcast Network through Wilfred Laurier University Press and creating a process for peer reviewing podcast content. The issue of peer review for podcasts is taken up more fully in the recent book by Beckstead, Cook, and McGregor titled Podcast or Perish: Peer Review and Knowledge Creation for the 21st Century (2024).

In our experience at an AAU institution, our podcasts were viewed as positive and legitimate scholarly endeavors. Consistent with Paulson et al. (2024) arguments, we emphasize that we do not see scholarly podcasts as equivalent to or a replacement for peer-reviewed journal publications. In fact, part of the value of podcasts is in their differences from peer-reviewed journal publications (e.g., audio format, easy to access, conversational in nature, fast publication, etc.). As indicated here, the conversations about issues surrounding peer review and social scholarship are still in their early stages.

Conclusion

Scholarly podcasts are designed to provide discipline-specific audiences with information from experts in an accessible format. This study utilized a multiple case study approach to evaluate multiple sources of data from producers and hosts of six scholarly podcasts originating from one higher education institution to contribute to the literature base. Given the proliferation of scholarly podcasts and podcasts in general, our research team wanted to better understand how we might communicate the value of scholarly podcasting to colleagues and university leaders. We aimed to compile and synthesize opportunities and challenges related to scholarly podcasting experienced by each of us so we may support others who are interested in communicating with broad audiences through podcasting. Our team found that podcast downloads and geographic reach are two measures of a podcast’s value that are widely understood. We also found that the standardized measures of the PSI (Singh et al., 2016) and the Listen Score may offer some utility in communicating quantitative metrics, when considered with additional contextualizing factors. Similarly, to recent scholarship (see e.g., Harrison & Loring, 2023), we found that limited time and attention created some of the most impactful challenges for members of our team with regard to continuous production of scholarly podcasts. As the host of Classroom Caffeine often says, starting a scholarly podcast is the easy part; sustaining it is the challenge. Podcasting takes dedicated time, energy, and money. It can be very challenging to go it alone; a team approach is best for impact and sustainability.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, L. Persohn. Some data are publicly available, while other data are only available to podcast producers through their podcast hosting platform.

References

About Us. Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities (APLU). (2023, October 27). https://www.aplu.org/about-us/

Beckstead, L., Cook, I. M., & McGregor, H. (2024). Podcast or perish: Peer review and knowledge creation for the 21st century. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501385179.

Bornmann, L. (2017). Measuring impact in research evaluations: A thorough discussion of methods for, effects of and problems with impact measurements. Higher Education, 73, 775–787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-9995-x

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Boyer, E. (1996). The scholarship of engagement. Journal of Public Service and Outreach, 1(1), 11–20.

Broadus, R. N. (1987). Toward a definition of “bibliometrics.” Scientometrics, 12(5), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02016680

Cabrera, D., Roy, D., & Chisolm, M. S. (2018). Social media scholarship and alternative metrics for academic promotion and tenure. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 15(1), 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2017.09.012

Cook, I. M. (2023). Scholarly podcasting: Why, what, how? Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003006596

Copeland, S., and H., McGregor. (2021). A guide to academic podcasting. Amplify Podcast Network. https://scholars.wlu.ca/books/2

Cox, M., Harrison, H. L., Partelow, S., Curtis, S., Elser, S. R., Hammond Wagner, C., Hobbins, R., Barnes, C., Campbell, L., Cappelatt, L., De Sousa, E., Fowler, J., Larson, E., Libertson, F., Lobo, R., Loring, P., Matsler, M., Merrie, A., Moody, E., ... & Whittaker, B. (2023). How academic podcasting can change academia and its relationship with society: A conversation and guide. Frontiers in Communication, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1090112.

Danford, N. C., Bixby, E. C., & Levine, W. N. (2022). Current status of podcasts in orthopaedic surgery practice and education. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 30(4), 141–147. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00856

DeMarco, C. (2022). Hear here! The case for podcasting in research. Journal of Research Administration, 53(1), 30–61.

Diebold, J., Sperilich, M., Heagle, E., Marris, W., & Green, S. (2020). Trauma talks: Exploring personal narratives of trauma-informed care through podcasting. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2020.1820425

Dong, J., Khalid, M., Murdock, M., Dida, J., Sample, S., Trotter, B., & Chan, T. M. (2020). MacEmerg Podcast: A Novel Initiative to Connect a Distributed Community of Practice. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10550

Elmore, S. A. (2018). The Altmetric attention score: What does it mean and why should I care? Toxicologic Pathology, 46(3), 252–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192623318758294

Figueroa, M. (2022). Podcasting past the paywall: How diverse media allows more equitable participation in linguistic science. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 42, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190521000118

Fronek, P., Boddy, J., Chenoweth, L., & Clark, J. (2016). A report on the use of open access podcasting in the promotion of social work. Australian Social Work, 69(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2014.991338

Galligan, F., & Dyas-Correia, S. (2013). Altmetrics: Rethinking the way we measure. Serials Review, 39(1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.serrev.2013.01.003

García-Villar, C. (2021). A critical review on altmetrics: Can we measure the social impact factor? Insights into Imaging, 12(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-021-01033-2

Ghose, A., & Ipeirotis, P. (2006). Designing ranking systems for consumer reviews: The impact of review subjectivity on product sales and review quality. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual Workshop on Information Technology and Systems, (pp. 303–310).

Gilstrap, D. L., Whitver, S. M., Scalfani, V. F., & Bray, N. J. (2023). Citation metrics and Boyer’s model of scholarship: How do bibliometrics and altmetrics respond to research impact? Innovative Higher Education, 48(4), 679–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09648-7

Greenhow, C., & Gleason, B. (2014). Social scholarship: Reconsidering scholarly practices in the age of social media. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(3), 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12150

Harrison, H. L., & Loring, P. A. (2023). PubCasts: Putting voice in scholarly work and science communication. Science Communication, 45(4), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470231186397

Hennig, N. (2017). Podcast literacy: Educational, accessible, and diverse podcasts for library users. Library Technology Reports, 53(2), 30–38. Huberman lab. Huberman Lab. (n.d.). https://www.hubermanlab.com/

Husain, A., Repanshek, Z., Singh, M., Ankel, F., Beck-Esmay, J., Cabrera, D., Chan, T.M., Cooney, R., Gisondi, M., Gottlieb, M., Khadpe, J., Repanshek, J., Mason, J., Papanagnou, D., Riddell, J., Trueger, N.S., Zaver, F., & Brumfield, E. (2020). Consensus guidelines for digital scholarship in academic promotion. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 21(4), 883. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.4.46441

Johng, S., Mishori, R., & Korostyshevskiy, V. (2021). Social media, digital scholarship, and academic promotion in US medical schools. Family Medicine, 53(3), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.22454/fammed.2021.146684

Kenna, H., Swanson, A. N., & Roberts, L. W. (2017). Evidence-based metrics and other multidimensional considerations in promotion or tenure evaluations in academic psychiatry. Academic Psychiatry, 41(4), 467–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0741-1

Kidd, W. (2012). Utilising podcasts for learning and teaching: A review and ways forward for e-Learning cultures. Management in Education, 26(2), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020612438031

Kinkaid, E., Emard, K., & Senanayake, N. (2020). The podcast-as- method?: Critical reflections on using podcasts to produce geographic knowledge. Geographical Review, 110(1–2), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12354

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Levin, G., Harrison, R., Meyer, R., & Ramirez, P. T. (2023). Impact of podcasting on novel and conventional measures of academic impact. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer, 33, 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2022-004114

Lim, M., & Swenson, R. (2021). Talking plants: Examining the role of podcasts in communicating plant pathology knowledge. Journal of Applied Communications, 105(2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.2366

Listen Notes. (n.d.). Listen score: How popular a podcast is? Retrieved May 11, 2023, from https://www.listennotes.com/listen-score/

Loeb, S., Sanchez Nolasco, T., Siu, K., Byrne, N., & Giri, V. N. (2023). Usefulness of podcasts to provide public education on prostate cancer genetics. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases, 26, 772–777. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-023-00648-4

MacGregor, S., & Cooper, A. (2020). Blending research, journalism, and community expertise: A case study of coproduction in research communication. Science Communication, 42(3), 340–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547020927032

Merriam, S. B. (1996). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

McNall, M., Reed, C. S., Brown, R., & Allen, A. (2009). Brokering community–university engagement. Innovative Higher Education, 33(5), 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-008-9086-8

Mobasheri, A., & Costello, K. E. (2021). Podcasting: An innovative tool for enhanced osteoarthritis education and research dissemination. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage Open, 3(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2020.100130

Monk, J. K., Bordere, T. C., & Benson, J. J. (2021). Emerging ideas. Advancing family science through public scholarship: Fostering community relationships and engaging in broader impacts. Family Relations, 70(5), 1612–1625. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12545

Moore, T. (2022). Pedagogy, podcasts, and politics: What role does podcasting have in planning education? Journal of Planning Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X221106327

Moore, J. B., Maddock, J. E., & Brownson, R. C. (2018). The role of dissemination in promotion and tenure for public health. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 24(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000691

Naff, D. B. (2020). Podcasting as a dissemination method for a researcher-practitioner partnership. International Journal of Education Policy & Leadership, 16(13), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.22230/ijepl.2020v16n13a923

Nwosu, A. C., Monnery, D., Reid, V. L., & Chapman, L. (2017). Use of podcast technology to facilitate education, communication and dissemination in palliative care: The development of the AmiPal podcast. Bmj Supportive & Palliative Care, 7(2), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001140

O’Meara, K. (2015). How ‘Scholarship Reconsidered’ disrupted the promotion and tenure system. In T. Ream’s (Ed.), Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. John Wiley & Sons.

Page, L., Hullett, E. M., & Boysen, S. (2020). Are you a robot? Revitalizing online learning and discussion boards for today’s modern learner. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 68(2), 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2020.1745048

Paulson, A. E., Clement, R. C., Holt, J. B., Sanders, J. S., & Louer, C. R., Jr. (2024). Orthopaedic surgery subspecialty podcast effectively disseminates peer-reviewed articles relative to traditional online publishing. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 44(3). https://journals.lww.com/pedorthopaedics/fulltext/2024/03000/orthopaedic_surgery_subspecialty_podcast.25.aspx

Peoples, B., & Tilley, C. (2011). Podcasts as an emerging information resource. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 18(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2010.550529

Persohn, L. & Branson, S.M. (in review). Scholarly podcasting for research dissemination: A scoping review.

Ream, T. C., Devers, C. J., Pattengale, J., & Drummy, E. (2019). The promise and peril of the public intellectual. In M. Paulsen & L. Perna (Eds.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03457-3_6

Sandmann, L. R., & Weerts, D. J. (2008). Reshaping institutional boundaries to accommodate an engagement agenda. Innovative Higher Education, 33, 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-008-9077-9

Semingson, P., O’Byrne, I., Alberto Mora, R., & Kist, W. (2017). Social scholarship and the networked scholar: Researching, reading, and writing the web. Educational Media International, 54(4), 360–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2017.1391525

Singer, J. B. (2019). Podcasting as social scholarship: A tool to increase the public impact of scholarship and research. JOurnal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 10(4), 571–590. https://doi.org/10.1086/706600

Singh, D., Alam, F., & Matava, C. (2016). A critical analysis of anesthesiology podcasts: Identifying determinants of success. JMIR Medical Education, 2(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2196/mededu.5950

Smith, P. (2023). Black immigrant literacies: Intersections of race, language, and culture in the classroom. Teachers College Press.

Taylor, Z. W., Taylor, M. Y., & Childs, J. (2023). “A broader audience to affect change?”: How education faculty conceptualize “audience” when producing public scholarship. Innovative Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09687-0

Thoma, B., Murray, H., Huang, S.Y.M., Milne, W.K., Martin, L.J., Bond, C.M., Mohindra, R., Chin, A., Yeh, C. H., Sanderson, W. B., & Chan, T.M. (2018). The impact of social media promotion with infographics and podcasts on research dissemination and readership. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 20(2), 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2017.394

Wade Morris, J. (2021). Infrastructures of discovery: Examining podcast ratings and rankings. Cultural Studies, 35(4–5), 728–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2021.1895246

Williams, P. J. (2007). Valid knowledge: The economy and the academy. Higher Education, 54(4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9051-y

Williams, A. E. (2017). Altmetrics: An overview and evaluation. Online Information Review, 41(3), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-10-2016-0294

Young, C., Paige, D., & Rasinski, T. V. (2022). Artfully teaching the science of reading. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003218609

Yuan, S., Kanthawala, S., & Ott-Fulmore, T. (2022). “Listening” to science: Science podcasters’ view and practice in strategic science communication. Science Communication, 44(2), 200–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470211065068

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by an Interdisciplinary Research Grant by the University of South Florida Sarasota Manatee campus Office of Research.

We would like to thank Reviewers for their time and effort to review the manuscript. We sincerely appreciate your valuable comments and suggestions, which helped us in improving the quality of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declarations

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Persohn, L., Letourneau, R., Abell-Selby, E. et al. Podcasting for Public Knowledge: A Multiple Case Study of Scholarly Podcasts at One University. Innov High Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-024-09704-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-024-09704-w