Abstract

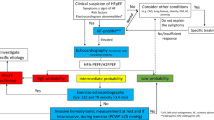

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a major and growing problem in the western hemisphere, affecting about 5 million patients in the United States. In daily practice patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) and significant angiographic coronary artery disease (CAD) are felt to have an ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICMP) and those without CAD or mild–moderate CAD out of proportion to the extent of LVSD are felt to have a non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (NICMP). Although invasive coronary angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of CAD, recent advances in non-invasive imaging have created multiple options for evaluating ICMP and NICMP. This review details the role of cardiac imaging in the diagnosis of ICMP and NICMP and outlines an algorithm of use of non-invasive tests in asymtomatic LVSD and symptomatic heart failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CA:

-

Coronary angiography

- CACS:

-

Coronary artery calcium score

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CCTA:

-

Coronary computed tomographic angiogram

- CHF:

-

Chronic heart failure

- CMR:

-

Cardiac magnetic resonance

- DE:

-

Delayed enhancement

- DCM:

-

Dilated cardiomyopathy

- EBCT:

-

Electron-beam computed tomography

- F18-FDG:

-

Fludeoxyglucose

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- ICMP:

-

Ischemic cardiomyopathy

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MSCT:

-

Multislice computed tomography

- N13-NH3 :

-

Nitrogen-13-Ammonia

- NICMP:

-

Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVSD:

-

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- RNV:

-

Resting radionuclide ventriculography

- RVEF:

-

Right ventricular ejection fraction

- SPECT:

-

Single-photon emission computed tomography

- SSS:

-

Summed stress score

- Tc-99m:

-

Technetium-99m

- WMA:

-

Wall motion abnormalities

References

Association AH (2003) American Heart Association Heart and Stroke Statistics, 2004 Update. [cited 2006 August 21]; Available from: http://www.americanheart.org

Hunt S (2005) ACC/AHA guideline update for CHF. JACC 46(6):e1–e82

Bart BA et al (1997) Clinical determinants of mortality in patients with angiographically diagnosed ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 30(4):1002–1008

Felker GM, Shaw LK, O’Connor CM (2002) A standardized definition of ischemic cardiomyopathy for use in clinical research. J Am Coll Cardiol 39(2):210–218

Gheorghiade M, Bonow RO (1998) Chronic heart failure in the United States: a manifestation of coronary artery disease. Circulation 97(3):282–289

Gheorghiade M et al (2006) Navigating the crossroads of coronary artery disease and heart failure. Circulation 114(11):1202–1213

Machac J et al (2006) Positron emission tomography myocardial perfusion and glucose metabolism imaging. J Nucl Cardiol 13(6):e121–e151

Elefteriades JA et al (1993) Coronary artery bypass grafting in severe left ventricular dysfunction: excellent survival with improved ejection fraction and functional state. J Am Coll Cardiol 22(5):1411–1417

Beanlands RS et al (2002) Positron emission tomography and recovery following revascularization (PARR-1): the importance of scar and the development of a prediction rule for the degree of recovery of left ventricular function. J Am Coll Cardiol 40(10):1735–1743

van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY et al (2010) Peripartum cardiomyopathy as a part of familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 121(20):2169–2175

Nieminen MS et al (2005) Executive summary of the guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of acute heart failure: the Task Force on Acute Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 26(4):384–416

Feigenbaum H, Armstrong W, Ryan T (2005) Feigenbaum’s echocardiography, 6th edn. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia

Schinkel A, Bax J, Boersma E (2002) Assessment of residual myocardial viability i nregions with chronic electrocardiographic Q-wave infarction. Am Heart J 144:865–869

Marwick TH, Narula J (2010) Contrast echocardiography: over-achievement in research, under-achievement in practice? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 3(2):224–225

Goldstein JA et al (1990) Determinants of hemodynamic compromise with severe right ventricular infarction. Circulation 82(2):359–368

Kinch JW, Ryan TJ (1994) Right ventricular infarction. N Engl J Med 330(17):1211–1217

Schuijf J, Shaw L, Wijns W (2005) Cardiac imaging in coronary artery disease: differing modalities. Heart 91:1110–1117

Sharp S, Sawada S, Segar D (1994) Dobutamine stress echocardiography: detection of coronary artery disease in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 24:934–939

Senior R, Janardhanan R, Jeetley P (2005) Myocardial contrast echocardiography for distinguishing ischemic from nonischemic first-onset acute heartfailure: insights into the mechanism of acute heart failure. Circulation 112:1587–1593

Lima R (2003) Incremental value of combined perfusion and function over perfusion alone by gated SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging for detection of severe 3 vessel coronary artery disease. JACC 42:64–70

Schinkel A (2003) Incremental value of technecium-99m tetrofosmin myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac events. Am J Cardiol 91:408–411

Elhendy A et al (2003) Prognostic significance of fixed perfusion abnormalities on stress technetium-99m sestamibi single-photon emission computed tomography in patients without known coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 92(10):1165–1170

Eichhorn E, Kosinski E, Lewis S (1988) Usefulness of dypyridamole-thallium-201 perfusion scanning for distinguishing ischemic from nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 62:945–951

Danias P, Ahlberg A, Clark B (1998) Combined assessment of myocardial perfusion and left ventricular function with exercise technetium-99m sestamibi gated single-photon emission computed tomography can differentiate between ischemic and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 82:1253–1258

Tian Y et al (2000) Radionuclide techniques for evaluating dilated cardiomyopathy and ischemic cardiomyopathy. Chin Med J 113(5):392–395

Bulkley B (1977) Thallium 201 imaging and gated cardiac blood pool scans in patients with ischemic and idiopathic congestive cardiomyopathy. A clinical and pathologic study. Circulation 55:753–760

Dunn RF et al (1982) Comparison of thallium-201 scanning in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and severe coronary artery disease. Circulation 66(4):804–810

Glamann D et al (1992) Utility of various radionuclide techniques for distinguishing ischemic from non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Arch Intern Med 152(4):769–772

Greenberg J et al (1985) Value and limitations of radionuclide angiography in determining the cause of reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: comparison of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 55(5):541–544

Juilliere Y et al (1993) Radionuclide assessment of regional differences in left ventricular wall motion and myocardial perfusion in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 14(9):1163–1169

Bengel F, Higuchi T, Javadi M (2009) Cardiac positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 54:1–15

Schinkel A, Bax J, Poldermans D (2007) Hibernating myocardium: diagnosis and patient outcomes. Curr Probl Cardiol 32:375–410

Eisenberg J, Sobel B, Geltman E (1987) Differentiation of ischemic from nonischemic cardiomyopathy with positron emission tomography. Am J Cardiol 59:1410–1414

Geltman E (1991) Metabolic imaging of patients with cardiomyopathy. Circulation 84:1265–1272

Slart RHJA et al (2005) Comparison of 99mTc-sestamibi/18FDG DISA SPECT with PET for the detection of viability in patients with coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction. Eur J Nuc Med Mol Imaging 32(8):972–979

Slart RHJA et al (2006) Prediction of functional recovery after revascularization in patients with chronic ischaemic left ventricular dysfunction: head-to-head comparison between 99mTc-sestamibi/18F-FDG DISA SPECT and 13N-ammonia/18F-FDG PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 33(6):716–723

Mody F, Brunken R, Stevenson L (1991) Differentiating cardiomyopathy of coronary artery disease from nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy utilizing positron emmission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 17:373–383

Berry J, Hoffman J, Steenbergen C (1993) Human pathologic correlation with PET in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Nucl Med 34:39–47

Dorbala S et al (2009) Incremental prognostic value of gated Rb-82 positron emission tomography myocardial perfusion imaging over clinical variables and rest LVEF. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2(7):846–854

Leber AW et al (2005) Quantification of obstructive and nonobstructive coronary lesions by 64-slice computed tomography: a comparative study with quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol 46(1):147–154

Raff GL et al (2005) Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive coronary angiography using 64-slice spiral computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 46(3):552–557

Stein PD et al (2008) 64-slice CT for diagnosis of coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Am J Med 121(8):715–725

Araoz PA et al (2010) Dual-source computed tomographic temporal resolution provides higher image quality than 64-detector temporal resolution at low heart rates. J Comput Assist Tomogr 34(1):64–69

Achenbach S et al (2003) Tomographic coronary angiography by EBCT and MDCT. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 46(2):185–195

Achenbach S (2006) Computed tomography coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 48(10):1919–1928

O’Rourke RA et al (2000) American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Expert Consensus Document on electron-beam computed tomography for the diagnosis and prognosis of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 36(1):326–340

Gottlieb I et al (2010) The absence of coronary calcification does not exclude obstructive coronary artery disease or the need for revascularization in patients referred for conventional coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 55(7):627–634

Budoff MJ et al (1998) Usefulness of electron beam computed tomography scanning for distinguishing ischemic from nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 32(5):1173–1178

Andreini D et al (2007) Diagnostic accuracy of multidetector computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 49(20):2044–2050

Cornily JC et al (2007) Accuracy of 16-detector multislice spiral computed tomography in the initial evaluation of dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Radiol 61(1):84–90

Andreini D et al (2009) Sixty-four-slice multidetector computed tomography: an accurate imaging modality for the evaluation of coronary arteries in dilated cardiomyopathy of unknown etiology. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2(3):199–205

Ghostine S et al (2008) Non-invasive diagnosis of ischaemic heart failure using 64-slice computed tomography. Eur Heart J 29(17):2133–2140

le Polain de Waroux JB et al (2008) Combined coronary and late-enhanced multidetector-computed tomography for delineation of the etiology of left ventricular dysfunction: comparison with coronary angiography and contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J 29(20):2544–2551

Lima JA, Hare J (2007) Visualizing the coronaries in patients presenting with heart failure of unknown etiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 49(20):2051–2052

Blankstein R, Di Carli MF (2010) Integration of coronary anatomy and myocardial perfusion imaging. Nat Rev Cardiol 7(4):226–236

Hendel RC et al (2006) ACCF/ACR/SCCT/SCMR/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SIR 2006 appropriateness criteria for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group, American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Interventional Radiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 48(7):1475–1497

Yan AT et al (2006) Characterization of the peri-infarct zone by contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is a powerful predictor of post-myocardial infarction mortality. Circulation 114(1):32–39

Walsh TF, Hundley WG (2007) Assessment of ventricular function with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Cardiol Clin 25(1):15–33. v

Bellenger NG et al (2000) Reduction in sample size for studies of remodeling in heart failure by the use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2(4):271–278

Karamitsos TD et al (2009) The role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 54(15):1407–1424

Paelinck BP et al (2002) Assessment of diastolic function by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am Heart J 144(2):198–205

Ennis DB et al (2003) Assessment of regional systolic and diastolic dysfunction in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using MR tagging. Magn Reson Med 50(3):638–642

Klem I et al (2006) Improved detection of coronary artery disease by stress perfusion cardiovascular magnetic resonance with the use of delayed enhancement infarction imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 47(8):1630–1638

Nandalur KR et al (2007) Diagnostic performance of stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 50(14):1343–1353

Lee DC, Johnson NP (2009) Quantification of absolute myocardial blood flow by magnetic resonance perfusion imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2(6):761–770

Manning WJ (2006) Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Cardiol 29(9 Suppl 1):I34–I48

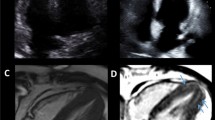

Soriano CJ et al (2005) Noninvasive diagnosis of coronary artery disease in patients with heart failure and systolic dysfunction of uncertain etiology, using late gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 45(5):743–748

Casolo G et al (2006) Identification of the ischemic etiology of heart failure by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging: diagnostic accuracy of late gadolinium enhancement. Am Heart J 151(1):101–108

Kim RJ et al (2000) The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. N Engl J Med 343(20):1445–1453

Selvanayagam JB et al (2004) Value of delayed-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in predicting myocardial viability after surgical revascularization. Circulation 110(12):1535–1541

Wagner A et al (2003) Contrast-enhanced MRI and routine single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) perfusion imaging for detection of subendocardial myocardial infarcts: an imaging study. Lancet 361(9355):374–379

Senthilkumar A et al (2009) Identifying the etiology: a systematic approach using delayed-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Heart Fail Clin 5(3):349–367 vi

McCrohon JA et al (2003) Differentiation of heart failure related to dilated cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease using gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation 108(1):54–59

Valle-Munoz A et al (2009) Late gadolinium enhancement-cardiovascular magnetic resonance identifies coronary artery disease as the aetiology of left ventricular dysfunction in acute new-onset congestive heart failure. Eur J Echocardiogr 10(8):968–974

Levine GN et al (2007) Safety of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiovascular devices: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Committee on Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiac Catheterization, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Circulation 116(24):2878–2891

Kanal E et al (2007) ACR guidance document for safe MR practices: 2007. AJR Am J Roentgenol 188(6):1447–1474

Thomsen HS (2009) Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: history and epidemiology. Radiol Clin North Am 47(5):827–831 vi

Weinreb JC, Abu-Alfa AK (2009) Gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: why did it happen and what have we learned? J Magn Reson Imaging 30(6):1236–1239

Zipes (2007) Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 8 edn. In: Saunders (ed)

Conflict of interest

Dr Ananthasubramaniam receives research grants from GE Healthcare, Molecular Insight Pharmaceuticals, Astellas Pharma Global Inc, American Society of Echocardiography and serves on the speakers bureau for Astellas Pharma Global Inc, Lantheus Medical Imaging and is a consultant with Lantheus Medical Imaging. Drs Dhar and Cavalcante have no disclosures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Drs Dhar and Cavalcante contributed equally to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ananthasubramaniam, K., Dhar, R. & Cavalcante, J.L. Role of multimodality imaging in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Rev 16, 351–367 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-010-9218-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-010-9218-y