Abstract

Ensuring equitable access to healthcare is important for universal health coverage (UHC). Using the enhanced two-step floating catchment area (E2SFCA) method, we found disparities in the spatial accessibility of outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities in the Philippines, particularly in the central and southern regions of the country. Municipalities with a higher proportion of older people had better spatial accessibility to outpatient care, while municipalities with a higher density of older people had better accessibility to inpatient care. Municipalities with high poverty rates had better accessibility to outpatient care but poorer accessibility to inpatient care. Addressing these disparities is essential for achieving UHC in the Philippines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Universal health coverage (UHC), whereby everyone can access high-quality and affordable healthcare regardless of who they are or where they live, is crucial for the well-being of society (World Health Organization et al., 2017). Spatial accessibility plays an important role in ensuring equitable access to healthcare. Spatial accessibility refers to the ease of access to healthcare, which has two key dimensions: availability (i.e., the number of available healthcare facilities, healthcare workers, or hospital beds), and accessibility (i.e., travel barriers such as distance or the time that people may face when trying to access healthcare facilities) (Guagliardo, 2004). Spatial accessibility to both outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities is essential for maintaining the health and improving the overall well-being of the population (Zhao et al., 2020). Better spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities enables the population to receive preventive care and aids management of chronic conditions, while better spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities increases the chance of early intervention and effective disease management.

Recently, there has been growing interest in the nationwide disparity in access to healthcare facilities, which is important for the planning and equitable distribution of healthcare for the general population (Wang, 2012; Zhao et al., 2020). However, empirical evidence from developing countries remains scarce. Previous studies conducted in Belgium (Dewulf et al., 2013), England (Bauer et al., 2018), Germany (Bauer et al., 2020), and Portugal (Lopes et al., 2019) revealed that spatial accessibility is higher in major urban areas and lower in suburban and rural areas. In Nepal, this pattern is even more pronounced in terms of inpatient healthcare facilities, including secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities (Cao et al., 2021). In South Korea, spatial accessibility is lower in rural, mountainous, and coastal areas than in metropolitan areas (Lee, 2022). The generally high spatial accessibility in urban areas is due to the greater concentration of healthcare facilities, healthcare workers, and transportation networks in urban areas than in rural areas (Cao et al., 2021; Dewulf et al., 2013). However, in the United States, spatial accessibility varies substantially depending on the type of healthcare provider. In urban areas, there is high spatial accessibility to internal-medicine physicians and specialists, while in rural areas spatial accessibility to family-medicine physicians and nurse practitioners is high (Naylor et al., 2019). In Australia, spatial accessibility to public hospitals is even higher in remote areas than in major cities, but accessibility to hospitals that provide inpatient care is much higher in the major urban areas (Song et al., 2018).

In addition to studies of rural–urban differences in spatial accessibility to healthcare facilities, it has been reported that demographic and socio-economic factors also play roles in access. In the United States, spatial accessibility to internal-medicine physicians and specialists is associated with the presence of medical schools, and higher levels of racial diversity and poverty (Naylor et al., 2019). In South Korea, a higher density of older people is associated with greater spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities and lower spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities.

The enhanced two-step floating catchment area (E2SFCA) method has been widely used to measure spatial accessibility. The E2SFCA has advantages over other methods because it considers both supply and demand, cross-boundary flows, and the distance-decay effect. The E2SFCA uses a special form of the supply–demand ratio called the spatial accessibility index (SPAI), which is easy to interpret and implement in a geographical information system (GIS). The SPAI is influenced by the supply volume, demand volume, and distance or travel time. Therefore, a larger healthcare supply, lower population demand, and lower geographic impedance result in higher SPAI values (Wan et al., 2012).

The Philippines is committed to achieving UHC and has thus enacted the Republic Act No. 11223, commonly known as the Universal Health Care Act, according to which everyone should have access to healthcare facilities regardless of their geographic location. However, few studies have assessed this commitment, especially in terms of spatial accessibility to healthcare facilities at the national scale. In the Philippines, there is an insufficient number of healthcare facilities and healthcare workers despite efforts by the government to support their construction, expansion, and modernization throughout the country. Although the Philippines still has a young population, the older population is growing rapidly. Projections indicate that the country will become an “ageing society” by 2032 and an “aged society” by 2069 (Reyes et al., 2019). Analyzing spatial accessibility to healthcare facilities is crucial to address disparities, allocate resources efficiently, and meet the evolving needs of an aging population, ensuring alignment with the goals of the Universal Health Care Act.

In this study, we had three objectives. First, we investigated nationwide spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities in the Philippines at the municipal level. Second, we investigated geographic clusters of spatial accessibility to these facilities. Finally, we explored the factors associated with spatial accessibility. We used the E2SFCA method to determine the spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities because it provides a more precise estimation of spatial accessibility than traditional methods.

Methods and materials

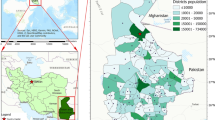

Study area

This nationwide study conducted in the Philippines took municipality/city as the unit of analysis. The Philippines is a country in Southeast Asia with a total land area of about 300,000 km2 and a population of approximately 100 million as of 2015. It is divided into 17 administrative regions, subdivided into 81 provinces, and further subdivided into 1,634 municipalities/cities, as of 2015. The Philippines has a healthcare system that consists of private and public healthcare facilities. Public healthcare facilities are largely financed through a tax-based budgeting system. The central government (Department of Health [DOH]) creates national health polices and regulates the healthcare system. It also manages and funds several tertiary and specialized hospitals at the national/regional level. Local governments (i.e., provinces and municipalities) manage and allocate funds for local public primary and secondary hospitals and health centers (i.e., facilities that provide preventive and promotive health services). Funding comes from various sources such as Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA), local and non-tax revenues, loans and grants, PhilHealth payments, and resources from the DOH, in cash or in kind. The private sector consists mainly of hospitals and clinics (i.e., facilities that provide consultations), which are unregulated, market-oriented, and focused on profits (Dayrit et al., 2018). Generally, private hospitals are better equipped than public hospitals. Access to healthcare facilities, whether public or private, depends on personal preferences, geographical location, and financial capacity, with no gatekeepers at the primary level of care. The number of public/private hospitals and health centers was 3,811 in 2016 (Dayrit et al., 2018), which increased to 4,368 in 2021 (DOH-KMITS, 2021). The total number of hospital beds increased from 79,444 in 2001 to 101,688 in 2016, but the number of beds per 100,000 population decreased from 110 in 2006, and to 100 in 2014 (The World Bank, n.d.). The private sector’s share of total hospital beds increased from 50.9% in 2011 to 53.4% in 2016 (Dayrit et al., 2018). The DOH regulates the establishment of new hospitals based on a set of established criteria.

Data and data sources

Four datasets were used in this study, including population data and location, healthcare facility information (e.g., hospitals and health centers), and municipal characteristics. To represent the population demand, the total population in each municipality was obtained from the 2020 Population Census in the Philippines provided by the Philippine Statistics Authority. The location of the population demand was represented by the population-weighted centroid of each municipality. This was calculated using 1-km grid population data in 2020 from the WorldPop Research Programme, which was obtained from the Living Atlas of the World by the Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI). The location (latitude/longitude) and number of beds of healthcare facilities in the Philippines in 2021 were provided by the Knowledge Management and Information Technology Service of the DOH. Data regarding the population density and the proportion of older people (defined as ≥ 60 years of age), land area, area type (rural or urban), income class, and municipality poverty incidence, were obtained from the Philippine Statistics Authority. The population density of older people and proportion of older people were computed based on the 2020 Census of Population and the official land area in square kilometers (https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-population-density-philippines-2020-census-population-and-housing-2020-cph). The area type and income class were from the Philippine Standard Geographic Codes (PSGC) database and masterlist as of fourth quarter of 2020 (https://psa.gov.ph/classification/psgc). The poverty incidence estimates were from the 2018 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates (https://psa.gov.ph/content/psa-releases-2018-municipal-and-city-level-poverty-estimates), and from the 2018 Updated Official Poverty Statistics for Highly Urbanized Cities (https://www.psa.gov.ph/content/updated-2015-and-2018-full-year-official-poverty-statistics). A map of the municipal boundaries of the Philippines in 2020 (in WGS84 datum) was downloaded from the Humanitarian Data Exchange of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (https://data.humdata.org/). As of 2020, the Philippines has 1,634 municipalities with a total population of 109,033,245. In total, 4,368 healthcare facilities distributed throughout the country were included in the study, of which 3,121 were health centers and 1,247 were hospitals, with 105,273 beds.

Data analysis

The analysis was conducted in three parts.

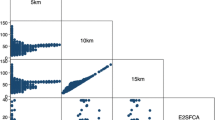

Estimating spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities in municipalities

The spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities for each municipality was proxied by the number of healthcare facilities, while the spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities was proxied by the number of hospital beds. The spatial accessibility to both outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities was calculated using the E2SFCA method in two steps. In the first step, the supply–demand ratio (Rj) was calculated for all municipal centroids (i) within the catchment area (d0) of each healthcare facility (j), as shown in Eq. 1:

Sj represents the supply (i.e., the number of healthcare facilities or number of beds at each healthcare facility (j)), and Pi represents the total population weighted by the function Wij,, which was calculated using Eqs. 2 and 3. Based on a commonly used threshold time (Bauer & Groneberg, 2016; Luo & Qi, 2009; Luo & Wang, 2003; Shah et al., 2020), a catchment area of 15 km was used for determining spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities and a catchment area of 30 km was used for determining spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities, which corresponded to 15- and 30-min travel times by car, respectively. A smaller catchment area was used to measure the accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities under the assumption that these facilities should be located close to the population for ease of access, while a larger catchment area was used to assess the accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities, considering that people may seek inpatient care or specialized treatments at hospitals located further away. In terms of travel impedance, the Euclidean distance in kilometers was used to measure the distance (dij) between the municipal centroid (i) and each outpatient and inpatient healthcare facility (j).

Function used for estimating the distance decay (Wij_hcf) of outpatient healthcare facilities

Function used for estimating the distance decay (Wij_hosp) of inpatient healthcare facilities

In the second step, for each municipal centroid (i), the SPAI was calculated by summing the Rj values obtained in step 1 for each healthcare facility (j) within the catchment area (d0) of the municipal centroid using Eq. 4:

The SPAI was then normalized using the average SPAI of all municipalities to obtain the spatial accessibility ratio (SPAR). A SPAR > 1 indicated better accessibility than the national average, while a SPAR < 1 indicated poorer accessibility than the national average.

Identifying geographic clusters of high/low spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities

Geographic clusters were identified using optimized outlier analysis (ESRI, n.d.). The tool first determined the optimal distance for defining the neighbors that will produce optimal cluster and outlier analysis results. Using this optimal distance, a spatial weight matrix was created to show the strength of the spatial relationship between a pair of municipalities i and j. Next, the local Moran’s I statistic was calculated for each municipality by comparing its spatial accessibility value with that of its neighboring municipalities. By examining this relationship, four types of geographical clusters were identified: clusters of municipalities with high spatial accessibility (hotspots, or high-high), clusters of municipalities with low spatial accessibility (coldspots, or low-low), clusters of municipalities with high spatial accessibility surrounded by municipalities with low accessibility (high–low), and clusters of municipalities with low spatial accessibility surrounded by municipalities with high accessibility (low–high) (Anselin, 2020).

Determinants of spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities

The association of spatial accessibility with municipal characteristics was investigated using a least squares regression analysis. The municipal characteristics considered were the population density of older people, proportion of older people, rural–urban classification, municipal income class, poverty incidence, and major island groups. Rural–urban classification is based on the Republic Act No. 9009, which classifies a municipality as “urban” if it has a locally generated average income of at least PHP 100M, a contiguous territory of at least 100 km2, and population of at least 150,000 (The LawPhil Project, 2001). The municipal income class is the classification of municipalities and cities into classes based on their average annual income determined according to Department of Finance (DOF) Department Order No. 23–08, July 29, 2008 (Department of Finance, n.d.). The city income classification used data as of June 2018, while 2016 for municipality income classification. The City and Municipality Income classes were reclassified into 12 categories (See Appendix). Poverty incidence was estimated as the ratio of the number of individuals with per capita annual income/expenditure less than the per capita poverty threshold to the total number of individuals within a municipality/city (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2019). Municipalities were classified into three major island groups: Luzon (north), Visayas (central), and Mindanao (south).

Software

ArcGIS Pro 3.2.1 was used to compute the population-weighted municipal centroid and conduct the optimized outlier analysis. The same software was also used to visualize all maps. For the computation of spatial accessibility indices, the “Accessibility” R package was used (Pereira and Herszenhut 2022). All other analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.2.3).

Results

Spatial accessibility

The SPAI was 0.5 (SD = 0.47) for outpatient healthcare facilities, indicating that there was less than one outpatient healthcare facility per 10,000 population. The SPAI was 6.3 (SD = 6.16) for inpatient care facilities, indicating that there were approximately six hospital beds per 10,000 population on average.

Figure 1 shows the map of SPAR to outpatient healthcare facilities in municipalities in the Philippines. Municipalities in the northwestern regions tended to have better spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities, while municipalities in central and southern regions had poorer and heterogeneous spatial accessibility, with remote areas having poor or even no spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities.

Figure 2 shows a map of the SPAR for inpatient healthcare facilities. Metropolitan areas (i.e., Metro Manila, Metro Cebu, and Metro Davao) and major cities across the country and their surrounding municipalities had better spatial accessibility. Municipalities with no spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities were scattered across the country, and were mostly on small islands or in remote areas.

Geographic clusters of spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities

Figure 3 shows the geographic clusters of spatial accessibility (SPAR) for outpatient healthcare facilities. Significant coldspots of municipalities were identified in northern, central, and southern regions. Within these coldspots, there were pockets of municipalities with high–low clusters. Hotspots were found in northwestern parts of the Philippines. These hotspots were bordered to the east by low–high cluster municipalities.

Figure 4 shows the geographic clusters of spatial accessibility (SPAR) for inpatient healthcare facilities. Coldspots were located in the central regions and their neighboring areas in the southern regions. Most of the cities within the coldspots formed pockets of high–low clusters. Hotspots were located in the northernmost and west-southernmost regions of the Philippines. Municipalities with low–high clusters were mostly located in coastal areas surrounding the hotspot municipalities.

Determinants of spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities

Table 1 shows the results of the least squares regression analysis between municipal characteristics and spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities in the Philippines. Municipalities with a higher proportion of older people, lower municipal income class, and higher poverty incidence were associated with higher spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities. Compared to Luzon, municipalities in Visayas and Mindanao were associated with poorer spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities. In terms of inpatient healthcare facilities, municipalities with a higher-density of older people were aassociated with higher spatial accessibility, while municipalities with a higher incidence of poverty were associated with poorer spatial accessibility. Compared to Luzon, municipalities in Mindanao were associated with higher spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities. Rural municipalities were associated with poorer spatial accessibility to both outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities.

Discussion

This study investigated spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities in municipalities in the Philippines and associated factors. There were two key findings. First, there was an apparent geographic divide in spatial accessibility to both outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities: municipalities with the poorest spatial accessibility were located in the central and southern regions of the Philippines, while the municipalities with better spatial accessibility were located in the northern region. Second, municipalities with a higher proportion of older people, lower income class, and higher poverty incidence had better spatial accessibility to outpatient care, while municipalities with dense older populations had better accessibility to inpatient care. Rural municipalities had poorer spatial accessibility to both inpatient and outpatient healthcare facilities.

Comparison with previous studies

Disparities in the spatial accessibility of outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities were apparent across municipalities. Rural and mountainous areas in the northern Philippines had higher spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities compared to urban areas. This finding differed from those in other countries, such as England (Bauer et al., 2018) and Belgium (Dewulf et al., 2013), where urban areas have higher accessibility to primary care physicians. In contrast, the disparities in spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities were more pronounced across the rural–urban continuum, with major cities having better accessibility, surrounding municipalities having fair accessibility, and remote areas having poor or no accessibility. Similar patterns have been observed in Germany for inpatient care (Bauer et al., 2020) and in Nepal for higher-level hospitals (Cao et al., 2021).

This study also identified differences in spatial accessibility between outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities, as also seen in Australia and the United States. In Australia, accessibility to public hospitals is higher in remote areas than in major urban areas for outpatient care, while accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities is higher in major urban areas than in rural areas (Song et al., 2018). In the US, accessibility to family medicine physicians and nurse practitioners is higher in rural areas, while accessibility to specialists is higher in urban areas (Naylor et al., 2019).

In terms of geographic clusters of spatial accessibility, major cities and metropolitan areas in the Philippines were identified as hotspots with higher spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities than other areas. Similar hotspot patterns were observed in Germany (Bauer et al., 2020) and South Korea (Lee, 2022), in which metropolitan areas had higher spatial accessibility to hospitals and clinics.

The findings of our least squares regression analysis showed that the spatial accessibility of the municipalities to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities was associated with socio-economic and demographic indicators. In South Korea, areas with a high-density of older people were associated with better spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities and lower spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities (Lee, 2022). In Zheijiang, China, and southwestern Ontario, Canada, municipalities with a higher proportion of older people have been reported to show poorer spatial accessibility (Jin et al., 2015; Shah et al., 2020), with older residents being more prevalent in rural areas where healthcare facilities are generally limited. In the Philippines, municipalities with a higher proportion of older people had better spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities, while municipalities with high density of older people had lower spatial accessibility to inpatient health care facilities.

There are associations of poverty incidence and the income of municipalities with accessibility to healthcare facilities. In agreement with previous studies (Ab Hamid et al., 2023; Bauer et al., 2020; McCrum et al., 2021; Naylor et al., 2019), we found that municipalities with a higher proportion of poor individuals were associated with poorer spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities, while municipalities with higher proportion of poor individuals and lower incomes were associated with better spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities. This implies that the allocation of public spending to healthcare facilities needs to be carefully balanced to achieve equitable access across different types of healthcare services.

Geographic divide in spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities

A divide between north and central–south regions was evident in this study, with better spatial accessibility in northern regions. This geographic divide can be attributed to several factors, including economic development, archipelagic geography, and security issues (i.e., insurgency). The northern region is more economically developed, with better access to healthcare facilities. This is because there is a higher concentration of both private and public healthcare facilities in this area, especially in Metro Manila and nearby municipalities, which accounts for at least 60% of the country's healthcare facilities and hospital beds (Dayrit et al., 2018; Naria-Maritana et al., 2021). In contrast, the central region, which consists of numerous islands, faces challenges due to its archipelagic geography. Economic development is concentrated on the larger islands, and poor transportation links between these islands make delivering healthcare services logistically and financially challenging. As a result, the central region has fewer health centers, public and private hospitals, and hospital beds compared to other regions (Dayrit et al., 2018). The southern region is the least economically developed due to a history of insurgency. Municipalities affected by conflict in this region tend to be among the poorest in the Philippines, lacking essential infrastructure, access to services like transportation and healthcare, and private sector investment.

Spatial accessibility to outpatient versus inpatient healthcare facilities

Spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities was relatively more equitable, favoring poor and older populations, as well as poor municipalities. Conversely, spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities tended to favor areas with a high-density of older people, non-poor population, and urban setting. This could be attributed to several factors related to the Philippine healthcare system, such as its prioritization of primary healthcare (PHC), healthcare governance, financing structure, and the roles in healthcare delivery of the public and private sectors, as well as PhilHealth.

Since 1979, the development of PHC has been the main approach of the Philippine government to ensure the health and well-being of its citizens. This approach involves designing, developing, and implementing health programs at the community level, with the DOH as the main manager and implementer. Primary care facilities (e.g., rural health centers and village health stations) were established to bring healthcare services closer to the people. However, in 1991 the responsibility for PHC administration was shifted from the DOH to local government units (LGUs) (Bautista, 2001; Lagrada-Rombaua et al., 2021; Naria-Maritana et al., 2021), which resulted in disparities in the access to and quality of healthcare services across the country due to the varying capacities of LGUs. Moreover, the financing of healthcare became inadequate and fragmented after the 1991 devolution, affecting the provision of different types of healthcare services. LGUs rely on various revenue sources, but disparities exist in funding, with municipalities primarily relying on internal revenue allotment (IRA), while cities can generate local funds through business or property tax in addition to IRA. Therefore, LGUs with limited revenue streams, particularly those situated in remote or island areas, may be lacking the funds necessary to establish and maintain healthcare facilities without financial assistance through loans or grants from the central government. Even in cities with higher revenues, funding may still be insufficient to establish and maintain hospital services (Dayrit et al., 2018; Lagrada-Rombaua et al., 2021). As a result, cities have tended to establish outpatient healthcare facilities, which have lower costs than inpatient healthcare facilities.

Policy implications

These findings have policy implications. First, there is a need to prioritize healthcare infrastructure development in areas lacking spatial accessibility, particularly in "coldspots." The establishment of new healthcare facilities should also focus on areas with significant older and poor populations, particularly in the rural and remote regions of Visayas and Mindanao. Second, it is essential to strengthen and expand healthcare facilities in underserved areas, especially those identified as "coldspots" for inpatient care. Rather than focusing solely on outpatient care, it is necessary to consider upgrading facilities to provide inpatient care, with priority given to expanding their bed capacity. Third, data-informed decision-making should be emphasized by conducting comprehensive analyses of the supply and demand of healthcare facilities, and the determinants of healthcare access. Finally, it is essential to establish standardized and transparent health resource allocation strategies that consider factors such as population size, age, sex profile, and socio-economic factors. This is important given the increased financial autonomy at the local government level and planned financial integration at the provincial level. Uniform resource allocation frameworks ensure fairness, efficient resource use, improved health outcomes, and a responsive healthcare system for all segments of society.

Limitations

This study had several limitations that need to be addressed in future studies. First, the measurement of impedance between supply and demand locations was based on a straight-line distance instead of road-network distance or travel time. However, previous studies (Apparicio et al., 2017; Bihin et al., 2022) have shown a strong correlation between Euclidean distance and network distance, implying that Euclidean distance can serve as suitable alternative when network distance or travel time calculations are complex. Second, the choice of catchment size and distance decay function in this study was arbitrary, although it was aligned with previous studies. A larger catchment size for rural areas should be considered because distance plays a more significant role in healthcare-facility choice for rural residents (Dewulf et al., 2013). Third, different types of hospitals were treated as the same in this study, despite variations in the quality and level of services they provide. In the Philippines, there is a hierarchical healthcare system with varying capacities across health centers and hospitals, including different levels of health services (primary, secondary, tertiary). These facilities all have outpatient departments accessible without gatekeeping. Hospitals are classified by the scope of service (general or specialty), and general hospitals are categorized into three levels based on their functional capacity (Levels 1–3). While patients can access different types of hospitals directly, ignoring their functional capacity may mask healthcare access disparities.

Conclusions

This study investigated the spatial accessibility to outpatient and inpatient healthcare facilities in the Philippines at the municipal level using the E2SFCA method and explored the municipal characteristics associated with spatial accessibility. The findings revealed that the central and southern regions of the Philippines are underserved. Furthermore, municipalities with a higher proportion of older people, poorer municipal income, and higher poverty incidence were associated with better spatial accessibility to outpatient healthcare facilities, while municipalities with a higher density of older people were associated with better spatial accessibility to inpatient healthcare facilities. Rural areas were associated with poorer spatial accessibility to both inpatient and outpatient healthcare facilities. It is necessary for the Philippine government to prioritize healthcare infrastructure development and strengthen existing facilities in underserved areas, especially in rural and remote regions, through data-informed decision-making and standardized resource-allocation strategies.

Data availability

The census of population data that support the findings of this study are available from the official statistics portal (https://psa.gov.ph/content/census-population-and-housing-report) of the Philippine Statistics Authority.

References

Ab Hamid, J., Juni, M. H., Abdul Manaf, R., Syed Ismail, S. N., & Lim, P. Y. (2023). Spatial Accessibility of Primary Care in the Dual Public–Private Health System in Rural Areas, Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043147

Anselin, L. (2020). Local Spatial Autocorrelation. https://geodacenter.github.io/workbook/6a_local_auto/lab6a.html#clusters-and-spatial-outliers

Apparicio, P., Gelb, J., Dubé, A. S., Kingham, S., Gauvin, L., & Robitaille, É. (2017). The approaches to measuring the potential spatial access to urban health services revisited: Distance types and aggregation-error issues. International Journal of Health Geographics, 16(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-017-0105-9

Bauer, J., & Groneberg, D. A. (2016). Measuring spatial accessibility of health care providers-introduction of a variable distance decay function within the floating catchment area (FCA) method. PLoS ONE, 11(7), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159148

Bauer, J., Müller, R., Brüggmann, D., & Groneberg, D. A. (2018). Spatial Accessibility of Primary Care in England: A Cross-Sectional Study Using a Floating Catchment Area Method. Health Services Research, 53(3), 1957–1978. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12731

Bauer, J., Klingelhöfer, D., Maier, W., Schwettmann, L., & Groneberg, D. A. (2020). Spatial accessibility of general inpatient care in Germany: An analysis of surgery, internal medicine and neurology. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76212-0

Bautista, V. A. (2001). Challenges to sustaining primary health care in the Philippines. Public Policy, 5(2), 89–127. Retrieved August 7, 2023, from https://cids.up.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Challenges-to-Sustaining-Primary-Healthcare-in-the-Philippines-vol.5-no.2-July-Dec-2001-5.pdf

Bihin, J., De Longueville, F., & Linard, C. (2022). Spatial accessibility to health facilities in Sub-Saharan Africa: Comparing existing models with survey-based perceived accessibility. International Journal of Health Geographics, 21(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-022-00318-z

Cao, W. R., Shakya, P., Karmacharya, B., Xu, D. R., Hao, Y. T., & Lai, Y. S. (2021). Equity of geographical access to public health facilities in Nepal. BMJ Global Health, 6(10), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006786

Dayrit, M., Lagrada, L., Picazo, O., Pons, M., & Villaverde, M. (2018). Philippines health system review 2018. Health Systems in Transition, 8(2), 1164. Retrieved August 4, 2023, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep28462.1

Department of Finance. (n.d.). LGU Income Class. Retrieved November 13, 2023, from https://blgf.gov.ph/lgu-income-class/

Dewulf, B., Neutens, T., De Weerdt, Y., & Van de Weghe, N. (2013). Accessibility to primary health care in Belgium: An evalution of policies awarding financial assistance in shortage areas. BMC Family Practice, 14(122), 1471–2296.

DOH-KMITS. (2021). List of Medical Facilities in the Philippines.

ESRI. (n.d.). Optimized Outlier Analysis (Spatial Statistics). Retrieved January 9, 2023, from https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/optimizedoutlieranalysis.htm

Guagliardo, M. F. (2004). Spatial accessibility of primary care: Concepts, methods and challenges. International Journal of Health Geographics, 3, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-3-3

Jin, C., Cheng, J., Lu, Y., Huang, Z., & Cao, F. (2015). Spatial inequity in access to healthcare facilities at a county level in a developing country: A case study of Deqing County, Zhejiang, China. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0195-6

Lagrada-Rombaua, L., Encluna, J., & Gloria, E. (2021). Financing Primary Health Care in the Philippines. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/media/59796

Lee, S. (2022). Spatial and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Accessibility to Healthcare Services in South Korea. Healthcare (Switzerland), 10(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10102049

Lopes, H. S., Ribeiro, V., & Remoaldo, P. C. (2019). Spatial Accessibility and Social Inclusion: The Impact of Portugal’s Last Health Reform. GeoHealth, 3(11), 356–368. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GH000165

Luo, W., & Qi, Y. (2009). An enhanced two-step floating catchment area (E2SFCA) method for measuring spatial accessibility to primary care physicians. Health & Place, 15(4), 1100–1107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.06.002

Luo, W., & Wang, F. (2003). Measures of Spatial Accessibility to Health Care in a GIS Environment: Synthesis and a Case Study in the Chicago Region. Environment and Planning b: Planning and Design, 30(6), 865–884. https://doi.org/10.1068/b29120

McCrum, M. L., Wan, N., Lizotte, S. L., Han, J., Varghese, T., & Nirula, R. (2021). Use of the spatial access ratio to measure geospatial access to emergency general surgery services in California. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 90(5), 853–860. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000003087

Naria-Maritana, M. J. N., Borlongan, G. R., Zarsuelo, M. A. M., Buan, A. K. G., Nuestro, F. K. A., Dela Rosa, J. A., Silva, M. E. C., Mendoza, M. A. F., & Estacio, L. R. (2021). Addressing primary care inequities in underserved areas of the Philippines: A review. Acta Medica Philippina, 54(6), 722–733. https://doi.org/10.47895/AMP.V54I6.2578

Naylor, K. B., Tootoo, J., Yakusheva, O., Shipman, S. A., Bynum, J. P. W., & Davis, M. A. (2019). Geographic variation in spatial accessibility of U.S. healthcare providers. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215016

Pereira, R., Herszenhut, D., & Institute for Applied Economic Research. (2022). Acccessibility: Transport Accessibility Measures (1.0.1). Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/accessibility/index.html

Philippine Statistics Authority. (2019). Technical Notes on the Generation of 2015 Small Area Estimates of Poverty. 632, 1–9. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://psa.gov.ph/system/files/phdsd/TechnicalNoteson2015SAE.pdf

Reyes, C. M., Arboneda, A. A., & Asis, R. D. (2019). Silver linings for the elderly in the Philippines: Policies and programs for senior citizens. PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2019–09. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/211083/1/1678591343.pdf

Shah, T. I., Clark, A. F., Seabrook, J. A., Sibbald, S., & Gilliland, J. A. (2020). Geographic accessibility to primary care providers: Comparing rural and urban areas in Southwestern Ontario. Canadian Geographer, 64(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12557

Song, Y., Tan, Y., Song, Y., Wu, P., Cheng, J. C. P., Kim, M. J., & Wang, X. (2018). Spatial and temporal variations of spatial population accessibility to public hospitals: A case study of rural–urban comparison. Giscience and Remote Sensing, 55(5), 718–744. https://doi.org/10.1080/15481603.2018.1446713

The LawPhil Project. (2001). Republic Act No. 9009. In The LawPhil Project (Issue c, pp. 1–712). https://lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2001/ra_9009_2001.html

The World Bank. (n.d.). Hospital beds (Per 1,000 people -Philippines). Retrieved May 13, 2023, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=PH

Wan, N., Zhan, F. B., Zou, B., & Chow, E. (2012). A relative spatial access assessment approach for analyzing potential spatial access to colorectal cancer services in Texas. Applied Geography, 32(2), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.05.001

Wang, F. (2012). Measurement, Optimization, and Impact of Health Care Accessibility: A Methodological Review. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102(5), 1104–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2012.657146

World Health Organization, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, & The World Bank. (2017). Tracking Universal Health Coverage : 2017 Global Monitoring Report. Retrieved May 13, 2023, from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/640121513095868125/pdf/122029-WP-REVISED-PUBLIC.pdf

Zhao, P., Li, S., & Liu, D. (2020). Unequable spatial accessibility to hospitals in developing megacities: New evidence from Beijing. Health and Place, 65(February), 102406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102406

Acknowledgements

This research was the result of the joint research with CSIS, the University of Tokyo (No. 1230). This research was financially supported by JSPS Kakenhi 19H05735, and by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by The University of Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception. Data preparation and analysis were performed by Novee Lor Leyso. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Novee Lor Leyso and Masahiro Umezaki reviewed and edited previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1 Income class recoding for cities and municipalities based on average annual income

Appendix 1 Income class recoding for cities and municipalities based on average annual income

Cities Income Class: | Average Annual Income | Coded as |

|---|---|---|

1st | P 400 M or more | 1 |

2nd | P 320 M or more but less than P 400 M | 2 |

3rd | P 240 M or more but less than P 320 M | 3 |

4th | P 160 M or more but less than P 240 M | 4 |

5th | P 80 M or more but less than P 160 M | 5 |

6th | Below P 80 M | 6 |

Municipalities Income Class: | Average Annual Income | |

1st | P 55 M or more | 7 |

2nd | P 45 M or more but less than P 55 M | 8 |

3rd | P 35 M or more but less than P 45 M | 9 |

4th | P 25 M or more but less than P 35 M | 10 |

5th | P 15 M or more but less than P 25 M | 11 |

6th | Below P 15 M | 12 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leyso, N.L., Umezaki, M. Spatial inequality in the accessibility of healthcare services in the Philippines. GeoJournal 89, 120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-024-11098-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-024-11098-3