Abstract

The paper is focused on the spatial differentiation of the quality of life at a district level, drawing data from the World Value Survey Round 7 (2017–2022). Spatial quality of life research in the traditional sense is based on the premise that quality of life is experienced by the individual in a physical geographical space, and therefore the research focuses on the objective, spatial dimension of quality of life, measured using the objective indicators, usually from statistical sources. The novelty of the paper lies in the premise that a spatial investigation of the subjective dimension of quality of life is also possible, focusing on the question of where people are satisfied with their lives. The indicator of this dimension is a self-related evaluation, obtained using the face-to-face method or the internet. In the case of the World Value Survey 7, data collection was done using the Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) technique. The aim of the paper is to conceptualize the subjective dimension of quality of life, apply the concept using data from WVS 7 and to find out which of the selected variables—also contained in WVS 7—are predictors of quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Quality of life

Reply from the President of the Slovak Academy of Sciences to a question in a public debate at the beginning of the millennium: what will be the greatest scientific challenge in the first decades of the 21st century?

The quality of life term expresses a subjective assessment of satisfaction with life. In recent decades, interest in it has been growing significantly (WHO, 2014). Babinčák (2013) illustrates this with the occurrence of the key word "quality of life" in the EBSCO publication database, which increased threefold in 2010 compared to 2000, and tenfold compared to 1990.

Some scholars who are concerned with quality of life are trying to conceptualize it. This applies to "general" quality of life (Liu, 1975; Ferriss, 2004; Phillips, 2006; Rojas, 2014; Murgaš, 2016; Lesková & Uhal, 2020), to "health related quality of life" (hereinafter referred to as HRQoL), (Anderson and Burckhardt, 1999; Owczarek, 2010) as well as for partial quality of life focused on working life (Da Silva, 2009) or universal social responsibility (Shek & Hollister, 2017). One of the few generally accepted insights regarding the epistemology of quality of life is the recognition of its two constituent parts—the subjective and the objective. Some scientists distinguish between subjective and objective dimensions of quality of life (Boelhouwer and Noll, 2014; Murgaš, 2016), other scientists distinguish between subjective quality of life and objective quality of life (Sirgy, 2012; Macků et al., 2020). The paper outlines the concept of quality of life based on the priority of its subjective dimension. However, the importance of the objective dimension in the form of exact data usually monitored by statistical offices on amenities in the narrower sense or exact complex data, including socio-economic and environmental in the broader sense, is not questioned. The objective dimension of the quality of life is spatially oriented. Unlike philosophy and psychology, which deal with man "in general", geography deals with man in a specific physical space.

The data for examining the subjective dimension are taken from the World Value Survey Round Seven (hereinafter referred to as WVS 7), (Haerpfer et. al., 2022). The paper is focused on Slovakia, the quality of life is explored at the level of its districts (in Slovak districts), in the statistical terminology of LAU 1. The aim of the paper is to conceptualize the subjective dimension of quality of life, to apply the concept using data from WVS 7 at the level of Slovak districts, to investigate their spatial differentiation and also to find out which of the selected variables are predictors of quality of life.

Background

Subjective and objective dimensions, subjective and objective indicators.

In the paper, quality of life is understood holistically as one. It follows that there is no subjective and objective quality of life, only quality of life with a subjective and objective dimension. Each of the dimensions consists of domains as clusters of variables or individual variables, the most appropriate term for measuring quality of life is indicators (Babinčák, 2013). The Australian Center on Quality of Life (2017) at Deakin University defines quality of life in terms of two dimensions: "Quality of life is both objective and subjective. Each of these two dimensions comprises several domains which, together, define the total construct. Objective domains are measured through culturally relevant indices of objective wellbeing. Subjective domains are measured through questions of satisfaction."

The subjective dimension of quality of life is connected with subjective indicators, in HRQoL referred to as "self-reported" quality of life (Aza et al., 2021), the objective dimension with objective indicators (Cummins, 2000; Slavuj, 2012). The controversy about whether subjective or objective indicators are better for investigating quality of life belongs to the big issue of quality of life.

Geographical approach to the study of quality of life

The quality of life is examined from a geographical aspect, the key point of which is understanding the connection between human life and space. Physical space, with its differentiated conditions, affects the experience of human life. Quality of life therefore also has a spatial dimension (Petrovič & Murgaš, 2020; Churski and Perdał, 2022; Lesková and Ilavska 2023). According to Schwanen and Atkinson (2015), geographers play an important role in the approach to quality of life in public policy. Ira and Kollar (1994) pointed out that geographically, the quality of life research belongs to behavioral geography.

While psychologists study how quality of life arises and what improves or erodes it, geographers study where quality of life values are low, medium and high. Because geography examines real physical space, the term "where" always refers to a given spatial unit, which may be the size of a city, region, or state. The geographical approach to the quality of life has been associated with the differentiation of objective indicators since the 1970s, when the Physical Quality of Life Index was created with the aim of measuring the quality of life with non-economic social indicators (Estes, 2014). This approach can be expressed as a search for an answer to the question: where are the good conditions for life? The ambition of the authors is to demonstrate that it is also possible to investigate a subjective indicator geographically, i.e. to answer the question where are people satisfied?

Investigating the quality of life is not determined by the objective geographical environment but by the subjective perception of this environment by the individual (Ira, 2017). According to Schwanen and Atkinson (2015), geographers play an important role in the approach to quality of life in public policy. Walmsley and Lewis (1993) rank quality of life as one of the most important areas of behavioural geographic research.

Quality of life

Quality of life is currently one of the most popular concepts. In the human, social and health sciences, quality of life is one of the most prominent issues (Faka, 2020), and interest in it is also expressed in public debates. This position is due to a combination of scientific and political interest and popularity in public discourse. Its occurrence, together with the occurrence of some selected terms, in science measured in the Web of Science database and in public space measured in Google in May 2023 is shown in Table 1.

The conceptualization of the quality of life, including its definition, is necessary due to the absence of its generally accepted definition and conceptual multiplicity, which has an impact on the theoretical level on the epistemology of the quality of life and on the practical level on the validity of data provided by leaders in public policy (Carlquist et al., 2016). Petrovič and Maturkanič (2022) state: "Quality of life is one of the concepts with which contemporary late modern society wants to grasp and express the socio-economic complexity of the period in which we live". Boelhouwer and Noll (2014) define "Quality of life is a normative conceptualization of the good life and society which—depending on its different notions—covers objective and/or subjective components".

“Quality of life is a new name for an old notion. It is a subjective name for the “well-being” of people and environment in which they live. For any individual, quality of life expresses that sets of "wants" which after being supplied, when taken together, makes the individual happy or satisfied. However, human wants rarely reach a state of complete satisfaction, except possibly for a very short time: as one want is satisfied, another pops up to take its place. As a result, the concept quality of life varies not only from person to person, but also from place to place and from time to time” (Liu, 1975: 1). Despite thousands of papers focused on the quality of life published after 1975, the quoted words do not lose any of their validity. It can be deduced from this that the essence of human beings does not change over time. The “gold standard of quality of life” was built on the same principle. "The essence of the gold standard of quality of life are quantifiable manifestations of the age-old archetypal human desire common to all people in human history: the desire to live long in health, in family, surrounded by children and later grandchildren; to be educated; to have a meaningful job which is fulfilling; and to be considered a good person and to have a good reputation, respectively" (Murgaš and Klobučník, 2016: 555).

As already mentioned, the quality of life consists of a subjective and an objective dimension, both of which are made up of domains or indicators. There is no consensus on which domains make up both dimensions, and naturally not even on the question of which indicators. Macků et al. (2021) provide an overview of domain occurrences for the years 1972–2018. The most frequent domains were Economic strength and material security, Health, Education, Environmental condition and Social environment.

Some authors consider quality of life, well-being and happiness as interchangeable synonyms (Tubergen et al., 2018), while others believe that quality of life is not interchangeable with well-being and happiness (Sirgy, 2012). Other authors consider quality of life and happiness as a component of well-being (Ruggeri et al., 2020). The paper is based on the belief that well-being and happiness are semantically different phenomena related to the quality of life, but they are not its synonyms (Carlquist et al., 2016).

Conceptualization of quality of life

The conceptualization of quality of life is based on the knowledge that it is holistic, it consists of two dimensions—subjective and objective, of which the subjective dimension is more important. The expression of subjective satisfaction is well-being, the expression of dissatisfaction is ill-being. The state when an individual does not evaluate satisfaction as well-being or ill-being is "neither well-being nor ill-being". Well-being and ill-being are therefore part of the quality of life. No one lives their life in a vacuum, everyone lives their life in a specific physical space. Evaluation of objective satisfaction is an evaluation of the qualities of a place in terms of objective conditions for experiencing a good life.

In the conceptualization of quality of life, it is necessary to state what quality of life is not:

-

Quality of life cannot be measured because it is a concept. What can be measured are its indicators.

-

Quality of life is not standard of living, income or prosperity.

-

Some authors identify quality of life with HRQoL (Owczarek, 2010). Health is an important partial domain of quality of life, but it is not synonymous with quality of life.

-

Quality of life is not an economic category and therefore cannot increase or decrease. It can be improving or eroding.

-

Quality of life is not happiness, well-being or ill-being. These phenomena are part of quality of life (Table 4).

The key point in conceptualizing quality of life is the individual and his or her subjective, cognitive-emotional assessment of satisfaction with his or her own life according to the idea that each of us has about the goodness of life. Opinions that the subjective assessment of life satisfaction should be rejected because of its subjectivity, and therefore inaccuracy, and therefore the only correct measurement of the quality of life is the measurement of objective indicators have features of social engineering are unacceptable. On the contrary, improving the quality of life—subjective in the form of psychological interventions and objective in the form of improving the quality of material and non-material amenities can only be achieved on the basis of knowledge of the level of quality of life, subjectively assessed by individuals (Carlquist et al., 2016).

Petrovič and Murgaš (2020a) expressed the conceptualization of quality of life with a model. The model is simplified in the form of Table 2 Modeling in the study of quality of life has a tradition, the "Having, Loving, Being" models (Alardt, 1993) or the Raphael et al. (1996) "Being, Belonging, Becoming" model are notorious. Veenhoven (2000, 2009) also uses graphic form to illustrate his conceptualizations of quality of life and well-being.

Examples of indicators for selected domains are shown in Table 3 for better clarity.

The only synonym for quality of life is satisfaction with life, because when we ask an individual what his or her quality of life is, we ask how satisfied he or she is with his or her life. Higher than average satisfaction, called well-being (lower than average satisfaction is ill-being) prevails in developed countries. Murgaš and Petrovič (2022) present the structure of ill-being and well-being on the Cantril scale in Table 4.

The essence of the quality of life concept is the following premises:

-

quality of life is a subjective cognitive and emotional evaluation of satisfaction with one's life according to the idea of a good life that each individual has.

-

quality of life is one. They are not "four qualities of life" (Veenhoven, 2000) in the sense of separate types of quality of life, as the "four qualities of life" term implies. An individual has a social life, family life, work life, sexual life, religious life, spends free time and is active in the community. These seven forms of life and others can be examined separately, but the examination of the quality of family life or the quality of spending free time is not the examination of the quality of life, only a part of it.

-

the quality of life is holistic, it consists of two dimensions—subjective and objective, of which the subjective dimension is more important.

-

the expression of subjective satisfaction is well-being, the expression of dissatisfaction is ill-being. The state when an individual does not evaluate satisfaction as well-being or ill-being is "neither well-being nor ill-being". Well-being and ill-being are therefore part of the quality of life.

-

the evaluation of objective satisfaction is the quality of the place.

Methodology

Data

The paper is based on data for Slovakia from the World Value Survey Wave 7 (Haerpfer et al., 2022). The survey focuses on capturing beliefs, values and motivations of people around the world in the topics as economic development, democratization, religion, gender equality, social capital, and subjective well-being. Thanks to this broad scope, it is also a suitable data source for research on quality of life, which is identified with the responses of individuals involved in the survey to question Q 49. The description of the survey is detailed in the World Value Survey (2022a), Technical Report, Slovakia, 2022.

The participants of the survey were 1200 inhabitants of Slovakia over the age of 18. According to (Haerpfer et al., 2022), samples are representative of all people aged 18 and above residing within private households in each country, regardless of their nationality, citizenship or language. Information about respondents is fully anonymised. The data was collected in Slovakia in January and February 2022. Data collection was carried out using the computer-assisted personal interviewing technique (CAPI). The complete questionnaire contains a total of 290 questions and their partial variants. For the purposes of our research in the context of quality of life, only some of them were selected, which are listed in Appendix A and Table 8 in the appendix of the paper.

Research design

After downloading the data for the whole of Slovakia, only responses to selected relevant questions were first filtered. Unfortunately, these are expressed by non-uniform response scales. This inappropriate design complicates uniform data processing and subsequent interpretation. For a simpler and more comparable interpretation of the individual questions, it was decided to recode the individual responses so that they are approximately comparable to the main scale in the range of 1–10, which is set for the Q49 key question. At the same time, the logic of higher value = more positive response was followed in the recoding.

Responses to Q49, Q50, Q164, Q288 questions have not been modified in any way as they are on a targeted scale of 1–10. Inconclusive responses of the type I don’t know/No answer/Not asked/Missing, unknown were omitted from the analysis.

In order to be able to evaluate the quality of life also in a geographical context, the input data of the individual responses of the respondents were reclassified according to their affiliation to the district in the form of one data representing the point estimate of the average answer to the question in the given district. The weighted average value was chosen as an aggregation indicator, since the average can be considered the best point estimate of the population parameters. Weighting was used in order to follow the original methodology of the survey authors, who always report the results constructed over the weighted data according to the Codebook Variables publication: "This weight is aimed at adjusting some sociodemographic characteristics in the sample population to the distribution of the target population. It has been computed using the marginal distribution of Age, Sex, Education and Region" (World Value Survey, 2022b). The geographic information in the source data is a code indicating the respondent's city of residence, including geographic coordinates. In a GIS environment, this information was converted to district affiliation using the Spatial Join tool. Calculated point estimates for selected questions were linked to spatial data for subsequent visualization options. Spatial data of administrative boundaries of Slovak districts were obtained from the Slovak Geoportal (online). The districts representing the internal division of the largest Slovak cities were merged into one (Bratislava, Košice). Spatial visualization was solved using the choropleth maps method.

Some of the selected questions describe a common latent variable, specifically Q58–Q63 questions describe the level of trust in different groups of people; selected Q164, Q171 and Q172 questions are focused on religiosity. To simplify the processed responses, these two groups of similar questions were aggregated into new sub-indices, i.e., the level of trust in different groups of people (QT) and the level of religiosity (QR). Aggregation took place using the sum of the average values of the responses to individual questions and their reclassification on the required scale of 1–10. This question could be replaced by question number Q57 in the case of trust towards different groups of people—"Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?". Due to the inappropriately designed answer scale (only two options: Most people can be trusted/Need to be very careful), the answer does not offer enough variability, and it can be very distorted. Therefore, it was decided to use the index compiled from Q58–Q63 questions.

Correlation and regression analysis was used to answer the partial aim in the form of a question, which of the monitored answers are related to the overall quality of life, or can be its predictors. While correlation describes a mutual linear dependence between two variables, regression analysis also tries to evaluate the expected causality, i.e. to mark some of the variables as cause and consequence. Although in the social sciences it is often very difficult to determine which of the phenomena is the cause and which is the consequence, for the needs of regression modelling a model was established where the overall quality of life is understood as the result of selected evaluated questions.

Measurement

The normal distribution of the response data to each question, as a prerequisite for choosing the correlation coefficient, was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test (Shapiro & Wilk, 1965). This tool tests the null hypothesis that the random sample comes from a normal distribution against the alternative hypothesis that the random sample is significantly different from the normal distribution. Subsequently, Pearson's correlation coefficient, which helps to measure how strong the linear relationship between two variables is, was used to express mutual correlations. Its value ranges from − 1 to 1, with 0 indicating no linear correlation, -1 indicating perfect negative linear correlation, and 1 indicating perfect positive linear correlation. The statistical significance of the detected correlations was further verified using the Pearson rank correlation test (Hollander et al., 2015).

While the correlation allows only the assessment of the degree of mutual linear ability, linear regression with quantitative predictors was used to evaluate the impact of individual predictors on overall quality of life. The general model represents e.g. James et al (2014):

where \(Y\) is the dependent variable, \({\beta }_{0}\) is the intercept, \({X}_{1}\dots {X}_{p}\) represent predictor matrices, \({\beta }_{1}\dots {\beta }_{p}\) are their coefficients, and \(\varepsilon\) is the vector of random errors. Only significant predictors were selected from all input questions—first the multicollinearity of the model was evaluated according to the VIF score (James et al 2014), then the optimal model was searched for by selecting only significant predictors.

Results

In the first step, the data was analysed for the whole of Slovakia using basic descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation), with the aim of finding out whether there are differences in the quality of life indicator in different classifications according to the categories of gender, age, place, education and self-assessment of health. The results are shown in Table 5.

It can be interpreted as meaning that quality of life values were good during the monitored period, even in the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. All categories of descriptive statistics have a value higher than 5.51 and therefore belong to the category of well-being, i.e. above average quality of life, according to Table 4.

The distribution of responses to each question is shown in Fig. 1, which shows the relative representation of each value of the reclassified responses. Although each question has a different number of possible answers, a unified visualization using a percentage stacked bar chart enables their mutual comparison. Positive answers predominate in most questions, except for Q57, Q61, Q62, Q63 (focused on trust in people) and Q171 questions. The representation of invalid responses is very low overall, with the highest representation (6.6%) for Q63 question.

Subsequently, individual questions were aggregated at the district level. All 1,200 individual responses (excluding non-valid results, which vary by question, see Fig. 1) were assigned to 50 districts out of a total of 72. The absence of responses in some districts thus created a spatial discontinuity. The number of responses in each district is variable and depends on the total population in the district—only 10 respondents were interviewed in the smallest districts (e.g. Senica), 100 respondents in the largest districts (Bratislava). For further processing, Q58–Q63 questions were aggregated into a level of trust in different groups of people (QT), Q164, Q171 and Q172 questions were further expressed as a level of religiosity (QR), as described in the Research Design chapter. The results at the aggregate level of the districts are supplemented with a boxplot visualization to show the variability of the answers to individual questions (Fig. 2). The most positive point evaluation is observed for question Q49 focusing on the overall quality of life. On the contrary, the average lowest rating was recorded for the degree of religiosity (QR), but this indicator also shows the most significant variability.

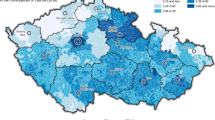

The main research question aims to investigate the quality of life in Slovak districts with the aim of revealing the spatial variability of the phenomenon. The determined values for the available districts are spatially visualized in Fig. 3. The logic of dividing the subjective quality of life scale into ill-being, neither ill-being nor well-being (in the map labelled as 'neutral') and well-being was used for the colour scale in the map.

The districts with the highest and lowest quality of life values are in Table 6.

Geographically, the quality of life values found in the selected districts can be interpreted as follows:

-

The quality of life in the surveyed districts is good, with an average quality of life value of 6.83 on a scale of 0–10, the district with the highest quality of life has a value of 8.88 and the district with the lowest quality of life has a value of 5.31.

-

In none of the evaluated districts was the value classified according to Table 4 as ill-being, ie. below average quality of life.

-

Due to the unavailability of information in some districts, the spatial distribution cannot be assessed continuously, using appropriate quantitative methods of spatial statistics. It can be concluded from the observed available data that the quality of life in the districts does not form clusters but is arranged in a mosaic. The regularity follows from Fig. 3 and only in the form of strips of districts with values of 6.5–7.5 from Považská Bystrica to Bratislava, from Bratislava to Nové Zámky and in the triangle of districts Kežmarok–Brezno–Gelnica in the east of Slovakia.

-

The districts in the east of Slovakia have the highest quality of life, two-thirds of the ten districts with the highest quality of life are in the regions of Košice and Prešov.

-

Districts with the lowest quality of life compared to the previous group are spatially differentiated differently. The districts belong to six of the eight Slovak regions. Six of the ten districts are located in the south of western, central and eastern Slovakia. It corresponds to the knowledge that the south of central and eastern Slovakia is socio-economically less developed compared to other parts of the country.

Correlation and regression analysis

The normality of data distribution was demonstrated using Shapiro test at α = 0.05 level of significance in all 7 selected questions. The relationship between the selected survey questions was examined in the next analytical step. Some questions were combined into a common index to describe the common latent variable "trust" and "religiosity" as already explained in the Research Design chapter. Therefore 7 variables entered the correlation analysis. The result of the correlations is arranged in a correlation matrix showing the values of Pearson's correlation coefficient and the resolution of whether the correlation was marked as significant using a statistical test, again at a significance level of α = 0.05 (Fig. 4).

The results show a number of significant correlations. The numerical value can be converted into a verbal description according to the classification proposed for the social sciences by De Vaus (2002): a strong positive correlation is expressed between Q49 and Q50 questions. A significant but negative correlation is observed in the Q50 and Q288 pair. A medium degree of correlation has a large representation, e.g. between questions Q47 and Q49, Q47 and Q131 or QT and QR.

The key question for this study is Q49 question, focusing on the overall quality of life. In the correlation matrix, we observe its significant relationship only to Q47, Q50 and Q131 questions. Since the correlation only describes the degree of mutual linear dependence, from a statistical point of view it is not the most suitable tool for answering the partial research question, which of the other researched topics can be a predictor of the quality of life. At the same time, the regression model can reveal other links between the dependent variable and other predictors, as it considers the relationships of several variables. Therefore, a regression model was also compiled, which determines the quality of life as a dependent variable, and other monitored questions as its predictors. Three significant variables at the significance level α = 0.05, namely Q47, Q50 and QT questions were identified in the model. The final model was compiled from them, the parameters of which are presented in Table 7.

The total predictive ability expressed by the adjusted index of determination (R2) reaches a value of 0.625, the selected predictors can therefore describe 62.5% of the variability of the observed quality of life. All predictors have a positive effect on the quality of life (as already identified in the correlation matrix). As a result of unification to the same 0–10 scale, we can interpret the regression coefficients as follows: if the level of subjective state of health (Q47) increases by 1, satisfaction with life (Q49) increases by 0.311 on average. If the level of satisfaction with financial situation (Q50) increases by 1, satisfaction with life (Q49) increases by 0.553 on average. If the level of trust to other persons (QT) increases by 1, satisfaction with life (Q49) increases by 0.273 on average. Satisfaction with financial situation is the most significant predictor of quality of life according to data aggregated by district and subsequently analysed using a regression model. Spatial visualization of significant predictors is shown in Fig. 5.

Discussion

The aim of the paper is formulated as conceptualization of the subjective dimension of quality of life, application of the concept using data from WVS 7 at the level of the districts of Slovakia, examination of their spatial differentiation and also to find out which of the selected variables are predictors of quality of life. Focusing on the question of where people are satisfied/dissatisfied with the quality of life is the focus of the objective dimension in the form of research where the objective conditions for experiencing a good life are transferred to the objective dimension. The paper thereby contributes to the development of the epistemology of quality of life.

Input data from the World Value Survey is a key element of the entire presented study. Although on a national scale the data meets the established quota selection, when moving to the regional level defined by the administrative boundaries of the districts, we encounter data limits in terms of the number of observations in individual administrative units. It is necessary to proceed with caution when generalizing the results to the total population in units with a small sample size, because the representativeness of the random sample may be impaired. The findings must be interpreted with the knowledge that the representativeness of the data may be compromised and that the opinions and attitudes of a few respondents may not reliably reflect the opinions and attitudes of the entire population. Therefore, it is advisable to interpret and extrapolate findings from such regions with caution. The limitation related to the number of responses in lower administrative units is also significantly reflected in the geographical aspect of the presented study. The discontinuity caused by not including some districts in the survey does not allow a complete spatial view of the investigated issue, and also prevents the use of some quantitative analyses suitable for working with spatial data. Spatial autocorrelation analysis is an example that allows identifying significant spatial clusters of high and low values, i.e. core areas of high/low quality of life. Missing localities also limit the identification of spatial trends in the distribution of quality of life, which would contribute to a deeper understanding of regional disparities in quality of life in Slovakia. In general, the problem of missing values could be solved e.g. by one of the imputation methods. However, the authors do not want to go for this solution as it would significantly increase the uncertainty of the results.

Quantification of vague phenomena from the field of sociological research represents another challenge in the presented study. In the topic of quality of life, due to the natural complexity and interdependencies, it is very difficult to determine which of the monitored phenomena is the cause and which is the consequence. In certain cases, the distinction between cause and effect becomes undefinable, which makes it difficult to establish a clear direction in relationships. This ambiguity makes the process of accurate measurement and analysis of social phenomena very challenging. However, for exact research, it is necessary to grasp these vague relationships in some way, as was also solved in the fulfilment of the partial aim of this study, looking for predictors of quality of life. We are aware that the presented regression model captures only one point of view to express causal relationships, with the absence of their clear evidence. Nevertheless, trying to grasp these relationships is essential for understanding the behaviour of the phenomenon under study and its interaction with other potentially related topics. The solution is to involve Slovakia in future rounds of the World Values Survey and thus obtain data for a longer period of time, which will significantly reduce the element of randomness not only in the study of geographical differentiation of quality of life, but also in other papers based on the World Value Survey outputs. However, this is the role of Slovak decision-making authorities.

Despite these limitations, the paper provides a basic understanding of the geographical differentiation of the quality of life in the districts of Slovakia, as described in the Results section. Two urban districts of Bratislava and Košice, the largest Slovak cities, were included in the measurement of WVS 7. Districts with regional headquarters and districts in Slovak conditions with large cities were also included. It is a realistic assumption that the geographical differentiation of the quality of life would not change significantly even in the case of data obtained from all districts of Slovakia.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to conceptualize the subjective dimension of quality of life and, using this concept, to evaluate the quality of life across Slovak districts using data from the WVS 7 survey. The results show that none of the evaluated districts showed below-average quality of life, referred to as ill-being, so the subjective perceptions of Slovak residents are positive. However, the identification of clear geographic patterns was limited due to missing data and the resulting spatial discontinuity.

Examination of the relationships between quality of life and its selected predictors using a regression model revealed only a limited number of relevant predictors. Self-reported state of health (Q47), satisfaction with financial situation (Q50), and the level of trust in different groups of people (artificially constructed question marked as QT) were identified as significant factors affecting the quality of life.

It is important to note that research on the findings of this study, and quality of life research in general, are limited by the availability and granularity of samples. The need for high quality and detailed data becomes evident especially in the geographic assessment of the subjective dimension of quality of life. Future research should focus on developing and conducting surveys that capture a wider range of variables and include larger sample sizes to ensure reliable and representative results. Further research on quality of life, focusing primarily on source data and their proper grasp by quantitative methods, is a necessary way to strengthen our understanding of the complex phenomenon of quality of life and can contribute to the development of targeted strategies and policies that improve the overall quality of life not only in Slovak districts.

References

Allardt, E. (1993). Having, loving, being: An alternative to the Swedish model of welfare research. In M. C. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life. Clarendon Press.

Anderson, K. L., & Burckhardt, C. S. (1999). Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life as an outcome variable for health care intervention and research. Journal of Advances Nursing, 29(2), 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00889.x

Australian Centre on Quality of Life. (2017). What is quality of life? Geelong, Victoria: Deakin University. Online. Retrieved 19 May 202 from https://www.acqol.com.au/about

Aza, A., Verdugo, M. Á., Orgaz, M. B., Amor, A. M., & Fernández, M. (2021). Predictive factors of self-reported quality of life in acquired brain injury: One-year follow-up. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030927

Babinčák, P. (2013). Measurement of quality of life: Overview studies analysis in selected data-bases. ČEskoslovenská Psychologie., 57(4), 358–371.

Boelhouwer, J., & Noll, H. H. (2014). Objective quality of life. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being Research. Springer.

Carlquist, E., Ulleberg, P., Delle Fave, A., Nafstad, H. E., & Blakar, R. M. (2016). Everyday understandings of happiness, good life, and satisfaction: Three different facets of well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 12, 481–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-016-9472-9

Churski, P., & Perdał, R. (2022). Geographical differences in the quality of life in Poland: Challenges of regional policy. Social Indicators Research, 164, 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02829-x

Cummins, R. A. (2000). Objective and subjective quality of life: An interactive model. Social Indicators Research, 52(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007027822521

Da Silva, M. (2009). Quality of work life. Concepts and relations with organizational performance. VDM.

De Vaus, D. (2002). Analyzing social science data. SAGE.

Estes, R. J. (2014). Physical quality of life index (PQLI). In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer.

Faka, A. (2020). Assessing quality of life inequalities. A geographical approach. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(10), 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9100600

Ferriss, A. L. (2004). The quality of life concept in sociology. The American Sociologist, 35(3), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-004-1016-3

Geoportál (online), Online. Retrieved June 4 2023 from https://www.geoportal.sk/en/zbgis/download/

Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E., & Puranen, B. (Eds.). (2022). World Values Survey: Round seven—country-pooled datafile. Madrid, Spain & Vienna. JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat.

Hollander, M., Wolfe, D. A., & Chicken, E. (2015). Nonparametric statistical methods. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119196037

Ira, V. (2017). Man and his activities in time and space. In F. Križan, K. Bilková, & P. Barlík (Eds.), Retail trade and the specifics of time-space behavior of consumers (pp. 3–18). Comenius University.

Ira, V., & Kollár, D. (1994). Behavioural-geographical aspects of environmental quality. GeoJournal, 32, 221–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01122112

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2014). An introduction to statistical learning. Springer.

Leskova, L., & Ilavska, L. H. (2023). Peer mediation as a means of eliminating conflict in the school environment. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 14(1), 161–184.

Lesková, L., & Uhal, M. (2020). The effects of Covid-19 on the Labor market and gender segregation with regard to helping professionals working in the field of Social services. Acta Missiologica, 14(2), 182–197.

Liu, B. (1975). Quality of life: Concept, measure and results. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 34(1), 1–13.

Macků, K., Caha, J., Pászto, V., & Tuček, P. (2020). Subjective or objective? How objective measures relate to subjective life satisfaction in Europe. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(5), 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9050320

Macků, K., Voženílek, V., & Pászto, V. (2021). Linking the quality of life index and the typology of European administrative units. International Development, 34(1), 145–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3586

Murgaš, F. (2016). Geographical conceptualization of quality of life. Ekológia (bratislava), 35(4), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1515/eko-2016-0025

Murgaš, F., & Klobučník, M. (2016). Does the quality of a place affect well-being? Ekológia (bratislava), 35(3), 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1515/eko-2016-0018

Murgaš, F., & Petrovič, F. (2022). Geography of well-being: Czech experience. Geographical Journal, 74(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.31577/geogrcas.2022.74.2.09

Owczarek, K. (2010). The concept of quality of life. Acta Neuropsychologica, 8(3), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203993590-12

Petrovič, F., & Maturkanič, P. (2022). Urban-rural dichotomy of quality of life. Sustainability, 2022(14), 8658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148658

Petrovič, F., & Murgaš, F. (2020a). Linking sustainability and happiness. What kind of happiness? GeoScape, 14(1), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.2478/geosc-2020-0007

Petrovič, F., & Murgaš, F. (2020b). Holistic and sustainable quality of life. Conceptualisation and application. Folia Geographica, 62(1), 77–94.

Phillips, D. (2006). Quality of life. Concept, policy and practice. Routledge.

Raphael, D., Rukholm, E., Brown, I., Hill-Bailey, P., & Donato, E. (1996). The quality of life profile—Adolescent version: Background, description, and initial validation. Journal of Adolescent Health, 19(5), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00080-8

Rojas, M. (2014). Quality of life, conceptualization. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 5360–5363). Springer.

Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á., et al. (2020). Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Quality Life Outcomes, 18, 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

Schwanen, T., & Atkinson, S. (2015). Geographies of wellbeing: An introduction. The Geographical Journal, 181(2), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12132

Shek, D. T. L., & Hollister, R. M. (2017). University social responsibility and quality of life: A global survey of concepts and experiences. Springer.

Sirgy, J. (2012). The psychology of quality of life. Hedonic well-being, life satisfaction, and eudaimonia. Springer.

Slavuj, L. (2012). Objective and subjective indicators in the research of the quality of life concept. Geoadria. https://doi.org/10.15291/geoadria.238

van Tubergen, A., Gulpen, A., Landewé, R., & Boonen, A. (2018). Are globals for health, well-being and quality of life interchangeable? A mixed methods study in ankylosing spondylitis patients and controls. Rheumatology, 57(9), 1555–1562. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key129

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(1), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010072010360

Veenhoven, R. (2009). Well-being in nations and well-being of nations. Social Indicators Research, 91, 5–21.

Walmsley, D. J., & Lewis, G. J. (1993). People and the environment: Behavioural approach in human geography. Longman.

World Health Organization and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (2014). Social determinants of mental health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2014. Online. Retrieved from May 19 2023 from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112828/9789241506809_eng.pdf

World Value Survey (2022a). Technical Report, Slovakia, 2022. Online. https://www.F00012240-WVS7_Survey_technical_report_Slovakia_2022(4).pdf. Accessed 27 Apr 2023

World Value Survey (2022b). World Values Survey Wave 7 (2017–2022). Variables Report. Online. from https://www.F00011055-WVS_7_Codebook_Variables_report. Accessed 10 June 2023

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic in cooperation with Centre for Scientific and Technical Information of the Slovak Republic. This paper was prepared with support from the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Science—grant number VEGA 1/0706/20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interest to disclose.

Human and animals rights

This chapter does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Description of the selected survey questions (Table

8).

Health

Q47. All in all, how would you describe your state of health these days? Would you say it is…: (Code one answer): 1 2 3 4 5

"trust".

Quality of life

Q49. All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days? Using this card on which 1 means you are "completely dissatisfied" and 10 means you are "completely satisfied" where would you put your satisfaction with your life as a whole? (Code one number): 1–10

Finances

Q50. How satisfied are you with the financial situation of your household? If '1' means you are completely dissatisfied on this scale, and '10' means you are completely satisfied, where would you put your satisfaction with your household's financial situation? (code one number): 1–10

Income group

Q288. On this card is an income scale on which 1 indicates the lowest income group and 10 the highest income group in your country. We would like to know in what group your household is. Please, specify the appropriate number, counting all wages, salaries, pensions and other incomes that come in. (Code one number): 1–10.

Trust

Q57. Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people? (Code one answer): 1–2

I would like to ask you how much you trust people from various groups. Could you tell me for each whether you trust people from this group completely, somewhat, not very much or not at all? (Read out and code one answer for each):

-

Q58 Your family 1 2 3 4

-

Q59 Your neighbourhood 1 2 3 4

-

Q60 People you know personally 1 2 3 4

-

Q61 People you meet for the first time 1 2 3 4

-

Q62 People of another religion 1 2 3 4

-

Q63 People of another nationality

Religiosity

Q164. How important is God in your life? Please use this scale to indicate. 10 means "very important" and 1 means "not at all important." (Code one number): 1–10

Q171. Apart from weddings and funerals, about how often do you attend religious services these days? (Code one answer): 1–7

Q172. Apart from weddings and funerals, about how often do you pray? (Code one answer): 1–8

Sense of security

Q131. Could you tell me how secure do you feel these days? 1–4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murgaš, F., Macků, K., Grežo, H. et al. The concept of quality of life and its application using the World Value Survey Wave 7: Slovak experience. GeoJournal 88, 6285–6302 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-023-10969-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-023-10969-5