Abstract

The theoretical link between endogenous cultural institutions (ECIs) and the regulation of natural resource access and use in sub-Saharan Africa is re-gaining its position in theory and practice. This is partly explained by growing resource use inefficiency, linked to predominantly exogenous, centralized institutions. The current situation has rekindled interest to understand what is left of ECIs that can support natural resource use and management in several natural resource contexts, including protected areas. To provide answers to these questions, in-depth studies with a geographic orientation are required. Put succinctly, a spaio-temporal evidence base of ECIs around protected areas is relevant in today’s dispensation. Such evidence is required for rich natural resource and culturally diverse settings such as Cameroon—having over 250 ethnic groups. This paper explores space time dynamics of ECIs around two of Cameroon’s protected areas—Santchou and Bakossi landscapes. Specifically we: (i) identified and categorized ECIs linked to protected area management, (ii) analyzed their spatio-temporal dynamics and discuss their implications for protected area management. The study is informed by key informant interviews (N = 22) and focus group discussions (N = 6). Using descriptive statistics, the key resources around these protected areas were categorized. Furthermore, narratives and thematic analysis constituted the key element of qualitative analysis. In addition, an analysis of the spatial distribution of ECIs was conducted. Based on our analysis, we derived the following conclusions: (1) Institutions that assume an endogenous cultural nature in some communities potentially exhibit an exogenous origin with a perennial nature; while some ECIs may assume ephemeral to intermittent nature, despite being culturally embedded in communities. (2) While present day ECIs regulate the use of natural resources around protected areas, they were not initially set up for this purpose. (3) Even within the same ethnic group, ECIs exhibit spatio-temporal variations. The results suggest the need for Cameroon’s on-going revision of the legal framework to emphasize context-specific elements of ECI which could leverage protected area management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Complex socio-ecological systems such as protected areas (PAs) require effective coordination and collaboration amongst overlapping spheres of governance (Manolache et al., 2018). Yet, such natural resource settings, have had their fair share of institutional arrangements which shape their use and management outcomes. While this holds true in several contexts, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) seemingly presents an important regional setting to understand this situation. SSA’s history of institutions span through pre-colonial (largely shaped by endogenous institutions), colonial, and post-colonial periods—largely dominated by exogenous, centralized institutions (Kimengsi & Balgah, 2017), and the so-called modern day institutions—driven by market and globalization forces. Institutions—defined as the humanly devised constraints that shape behavior and actions (protected area management in this case), continue to attract significant research interest (Kaimowitz & Angelsen, 1998; North, 1990). It will arguably continue to do so in the decades ahead (Kimengsi et al., 2021a, b; Osei-Tutu et al., 2014; Yeboah-Assiamah et al., 2019). Institutions could be viewed from several lenses: For instance, based on formality, formal institutions encompass written and codified laws, largely driven by national governments, while informal ones relate to unwritten or uncodified rules that are communicated through beliefs, customs and traditions, over generations (Osei-Tutu, 2017; Osei-Tutu et al., 2015; Yeboah-Assiamah et al., 2017). A more recent classification on the basis of timespan presents institutions as ephemeral,Footnote 1 very short-term arrangements made by resource management actors to minimize conflicts; partially enduring, arrangements that served as norms for a while but fizzle out as new actors take central stage (Kimengsi & Balgah, 2021; Kimengsi et al., 2021b); and enduring, where such institutions are codified (in the case of formal) and/or enforced beyond physical to include strong spiritual processes (Kimengsi & Balgah, 2017; Ostrom, 1990). The endogenous—exogenous dichotomy presents institutions introduced by the state and international agencies as exogenous in nature, while complex and embedded rules that are specific to communities and sometimes difficult to comprehend by external actors, are endogenous (Yeboah-Assiamah et al., 2017).

By and large, some institutions exert dominance over others in terms of their regulation of natural resource use and management. For instance, it has been widely held that exogenous, centralized institutions countervail endogenous, largely informal ones (Buchenrieder & Balgah, 2013). Our emphasis is on endogenous institutions, especially as it is argued that these forms of institutions are increasingly being rendered ineffective, transformed, or modified (Chabwela & Haller, 2010; Ensminger, 1997; Haller et al., 2018; Kimengsi et al., 2021a). We therefore seek to provide answers to the question, what is left of endogenous cultural institutions that can guarantee effective and efficient protected area (PA) management in countries of SSA? As a country in SSA, Cameroon presents a useful case study to understand the ‘health’ of culturally embedded (endogenous) institutions that define PA management. Cameroon hosts over 250 ethnic groups. The country’s ethnic fractionalizationFootnote 2 score (0.89) exceeds the SSA average of 0.71 (Fearon, 2003), making it a rich ‘laboratory’ to study and understand the spatio-temporal manifestations of the ‘last vestiges’Footnote 3 of endogenous cultural institutions. Furthermore, the country hosts more than 30 PAs spanning across different ecological zones which are characteristic of SSA. Bakossi and Santchou PAs are classical examples. While the former is found within the coastal socio-cultural setting of the country, the latter is located at a transition zone between the coastal setting and the humid montane (grassfield) setting. At the moment, knowledge on the categories of endogenous cultural institutions linked to the management of these PAs, and their spatio-temporal dynamics remain unknown. Put succinctly, while there are pointers to the fact that these institutions have witnessed changes, the extent to which such changes have occurred remains unknown. This mars progress towards the activation of endogenous cultural institutions. With the growing search for stable institutions around PAs, it is only germane to comparatively analyse the spatio-temporal dynamics and implications of ECIs, with a view to charting a way forward for the sustainable management of resources around both PAs. This paper therefore seeks to: (1) identify and categorize ECIs linked to PA management in Bakossi and Santchou, (2) analyze their spatio-temporal dynamics and (3) discuss their implications for PA management.

Analytical framework

Institutional theory explains both individual and organizational actions. Emphasis in the field of institutional theory is on the analysis of how institutions evolve over space and time (Greif, 2006; Greif & Laitin, 2004; Greif & Mokyr, 2016). In North’s view of institutional change, he underlined the inertial attributes of informal (largely endogenous) institutions, over formal ones (North, 1990). The author further theorized the existence of alterations for institutions. This is linked to discontinuous change processes such as revolutions or conquests (North, 1990, p. 36). Drawing from North (1990), we conceptualize institutions following the endogenous (informal) and exogenous (formal) analytical lens. Although we consider endogenous institutions as informal institutions here, it must be noted that institutions (formal and informal) have different levels of endogeneity. For instance, culturally-embedded rules in a community are endogenous in nature, and considered as informal, while state-driven rules introduced in such communities assume an exogenous (formal) attribute. However, when state rules interact with international rules, the former could be viewed as endogenous, and the later as exogenous institutions –both having a formal attribute. Furthermore, our analysis draws from geographical studies (Gomes et al., 2020) to classify institutions as ephemeral, intermittent and perennial institutions. Drawing from these classifications, we place emphasis on the structural and process dimensions of endogenous cultural institutions (ECIs) to identify and categorize ECIs linked to PA management in Bakossi and Santchou. Considering the diversity that exists in ECIs, even within a single cultural setting, we found it imperative to appreciate the distribution and manifestations of ECIs over space and time. These insights are useful in determining where ECIs are active in each of the PAs, and the extent to which they potentially shape the management of both PAs. Also, at the time when Cameroon is in the process of revising her forest policy, this evidence is helpful in the framing of policies that are friendlier and rooted in the manifestations of ECIs in the target PAs.

Study area and research methods

The Bakossi and Santchou PAs constitute two of the over 30 PAs found in Cameroon. Communities around these PAs have distinct cultural traits, making them useful sites to uncover the last vestiges of endogenous cultural institutions. The Bakossi protected area is located in the South West Region, while the Santchou protected area is found in the West Region, all in Cameroon (Fig. 1). Located in the predominantly French speaking region of Cameron, the Santchou protected area is home to the Mbo of the sawa tribes (Mbeng and Buba, 2017). However, there is growing cultural mix especially from the Bamileke tribal groups of the West region and several groups from the South West Region. The Bakossi PA is located in the English speaking region of Cameroon, indicating that her communities came under the influence of the British rule (Geschiere, 1993). The Bakossi Landscape is an outcrop of the Bakossi Forest which was formed under British colonial rule (1956). This was created with the intention to regulate forest use activities around this zone (Wild, 2004). Covering a total surface area of 29,320 ha, this area hosts the predominantly Bakossi tribe (Ejedepang-Koge, 1986; Wild, 2004). While there are traces of other ethnic groups, it is important to remark that this PA relatively has cultural intactness, mirrored through their stringent local laws (Ejedepang-Koge, 1986). Based on the 2007 Census, the Bakossi tribe had a population of about 200,000, with that of the Bakossi protected area inclusive (Sone, 2016). Important economic activities carried out by the local population in this area include hunting, farming, the harvesting of NTFPs and small scale logging (Ebua et al., 2013).

The creation of the Santchou PAs in 1947 by the French was prompted by the need to promote natural reforestation, execute reforestation and protect the existing biodiversity. This laid the ground works for the area to be transformed from a forest reserve into a wildlife reserve in 1986, owing to it playing host to important variety and density of animal species especially the dwarf elephant (Loxodontapumilio). Formal management of the reserve shifted from the Ministry of Agriculture, the General Delegation of Tourism and most recently, the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife (MINFOF). The Santchou PA has over 2265 inhabitants within the PA (Fokeng & Meli, 2015) with an adjacent urban population of more than 20,000 persons (Estrella & Marta, 2014). The economy of Santchou is largely agrarian, involving the practice of peasant market oriented agriculture (Fokeng & Meli, 2015; Marcel & Ajonina, 2021) Both cases form a good base for understanding the history and evolution of endogenous cultural institutions.

While both are PAs, the Bakossi is categorized as a national park. It gained the status following Prime Ministerial Decree N° 2007/1459/PM of 28 November 2007. The management paradigm in this area centered on protection of the forest and biodiversity, the promotion of ecotourism and other livelihood opportunities. At the village level, village forest management committees which are the lowest organs of forest resource management are found. Santchou is categorized as a wildlife reserve, having unique flora and especially fauna. Both sites are managed by conservators and forestry officials. Based on a reconnaissance survey conducted in early July 2020, the authors were led to develop a list of communities exhibiting attributes of ECIs which could mirror the situation of each of the PA. For Bakossi, 9 villages were identified. Furthermore, 7 communities were identified for Santchou. We then proceeded to randomly select three in each study site for the surveys to be conducted (Table 1).

Data collection

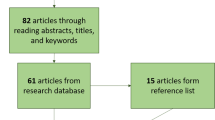

This research is a follow-up study on a previous research on institutional bricolage and forest use practices in Cameroon (see Kimengsi & Balgah, 2021) within the framework of the CAMFORST Project (for details, see: https://tu-dresden.de/forst/camforst). The previous study establishes the practice of bricoleurs as they draw from a range of formal and informal institutions to justify and navigate their forest use practices, but did not answer the question: what is left of protected area linked endogenous cultural institutions? This paved the way for another study with emphasis on clarifying what is left of endogenous cultural institutions. To generate data for this study, key informant interview (KII) and focus group discussion (FGD) guides were designed. The KII guide consisted of 12 questions which focused on the identification and categorization of ECIs linked to protected area management. Furthermore, the instruments emphasized on the determination of the diversity of ECIs within these settings, to enable the appreciation of their distribution and manifestations over space and time. It further captured questions linked to the policy implications of ECIs on PA management. A focus group discussion guide (N = 8) was equally prepared to capture questions linked to the characterization of endogenous cultural institutions, their nature (e.g. ephemeral, intermittent or perennial), the purpose for instituting ECIs and their activeness, from a spatio-temporal perspective. These instruments were used to conduct the KIIs and FGDs. Data collection ran from July to September 2020 involving a total of 22 KIIs; 12 in Bakossi and 10 in the Santchou PAs. Key informants involved traditional leaders, village elders, representatives of civil society, state forestry officials and forest resource users. Considering that the subject in question involved culturally-embedded institutions (ECIs), custodians of village traditions (e.g. traditional rulers and village elders) command extensive knowledge and experience on the working of ECIs in their respective communities. Furthermore, they could best identify the last vestiges of ECIs. State forestry officials function within the framework of formal institutions (state rules)—always in constant interaction with ECIs. It was therefore imperative to obtain information on some of the challenges linked to the co-existence of ECIs and formal rules, as well as to explore the extent to which both forms of institutions countervail each other. The civil society as a catalyzing agent (Haller et al., 2018; Kimengsi et al., 2019), facilitates the co-management of protected areas involving state and traditional authorities. They therefore provide a more unbiased view point on the situation of ECIs. Forest users’ views were sought, as they are directly implicated in rule (non)compliance in protected area resource use.

Participant observations and field visits were made by the researcher to collect relatively objective first-hand information on the state of endogenous cultural institutions and forest resource management. During this exercise, field notes were taken. A translator was hired to assist in data collection (in French) in the Santchou area. Besides field observations, 6 FGDs were carried out involving 3 in Santchou and 3 in Bakossi. The six FGDs involved 2 mixed groups, 1 female group 1 male group and 2 youth groups. A summary of the data collection methods is presented in Table 2. The interviews lasted between 40 and 60 min, while the FGDs lasted between 50 and 75 min. Emphasis during the data collection was on the resources of interest to communities around the protected areas, the identification and categorization of ECIs linked to the management of both protected areas, and on the spatio-temporal dynamics of protected area-linked ECIs. Prior experience in previous consultancy assignments and data collection phases informed the selection of relevant communities for data collection. The Lead author served as a consultant for WWF and partner Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) within the framework of the evaluation of rights based approaches, gender mainstreaming, negotiation and social mobilization in protected areas in Cameroon in 2016. Furthermore, between December 2018 and October 2019, he led a consultancy assignment to assess institutional barriers to women’s participation in natural resource decision-making around in selected protected areas—including the Bakossi protected area.Footnote 4 These assignments enabled the identification of relevant study sites to explore ECI change processes. Besides, previous empirical studies further informed the study sites selection: For instance, between December 2017 and January 2018, and from March to May 2020, data was obtained around the Bakossi and Santchou protected areas, on socially embedded customary rules that regulate forest use. This process further informed the selection of study sites (for details, please see Kimengsi & Balgah, 2021).

Field notes were used to record the interviews and FGDs. The points taken were further transcribed and coded before being summarized and presented in the results section. Besides narratives and thematic analysis, an analysis of the spatial distribution of ECIs was conducted. The analysis centred on the categorization of protected area resources and ECIs linked to their management, the spatio-temporal dynamics of protected area-linked ECIs, and on their implications for protected area management. Furthermore, in the analysis, we identified emerging themes/ patterns linked to the key questions the paper sought to address. In cases of ambiguity, the third author (who lives close to these communities) sought further clarification from our respondents. Descriptive statistics was performed to determine the key forest resources of interest to communities around the two protected areas. This provided useful insights on the forest resources that are prioritized by households around these PAs. Through descriptive analysis, we established the proportion of households that depend for instance, on firewood for household energy (especially cooking and heating). Since ECIs regulate access and use of these protected area resources, it was imperative to appreciate the resources that are implicated in the spatio-temporal changes of ECIs. For the analysis of the spatial distribution of ECIs, we generated data on the different ECIs linked to protected areas resource management through KIIs and FGDs. Furthermore, the KIIs and FGDs enabled us to select the active ECIs—the ‘last vestiges’ in both study sites. The discussions further aided in the identification of communities were such institutions are still strongly upheld. Maps were then used to depict the spatial dimension of these ECIs (Figs. 3 and 4).

Results

Key resources around PAs

The Santchou PA has numerous forest resources ranging from firewood, bush pepper and kolanuts. These resources vary in quantity or proportion with firewood being the most dominant forest resource (21.8%). It is the main source of energy for communities in and around the PA, as more than 95% of households depend on firewood for household energy (especially cooking and heating). Bush pepper is the second dominant forest resource in the PA (19.1%). Bush pepper serves as a major source of income. It is also used to prepare delicacies. Kola is the third dominant forest resource (18.2%) which is used to entertainment guests. It is also a source of income to the local population. Other forest resources include ngongo leaf, Njangsa and bush meat.

Similarly, the Bakossi protected area is also endowed with forest resources such as firewood, timber, bush pepper, Njangsa, and Ngongo leaf. Firewood is equally the dominant resource (19.1%). Timber species such as iroko, mahogany, Sappele and small leaves are significantly exploited (18.2%). Others include bush meat (8.2%) and Ngongo leaf (11.8%).

Identification and categorization of ECIs linked to protected area management

In the Santchou and Bakossi communities, different endogenous cultural institutions exist (Table 3) with different historical backgrounds. These institutions were adhered to with regards to the effective coordination and management of forest resources in and around both protected areas (PAs). With authority and rights bestowed on them by their subjects, they occupy a unique position in the management of forest resources and are seen as mediators between the local people and the state. Muakum is an ECI that embodies only the male population ranging from 19 years and above. It is the broadest in structure amongst other endogenous cultural institutions and it contributes vitally to the growth of communities in and around the Bakossi PA. For example, Muakum serves as peace making force to the local population. Ahon is the second influential institution in PA management. Just like Muakum, Ahon is a secret society with men. Members of this institution play the role of purification (against witchcraft), monitoring and obscuring the protected area from being over exploited and interfered by neighboring communities. Ahon is highly involved in the management of forest resources such as bush meat, timber and herbs.

Others include traditional councils such as Mbumauku and Mboumagie, which enforces sanctions to resource users around the Bakossi PA. Similarly, Abashi is found in communities in and around the Santchou PA except in Mogot. It is an influential structure in the Santchou PA which plays multiple roles in forest resource management. Abashi originated in Mamfe and was introduced and transplanted in communities in and around the Santchou protected area in 1990s. Furthermore, Afon is the second highest endogenous institutional structure this area.

Just like Abashi, Afon is also a secret society which is lodged in the protected area (forest) which serves as an ancestral home to the migrating population of these communities. Its role is linked to the conservation and regeneration of the forest and it resources. This is done by placing restrictions over the random exploitation of forest resources through beliefs and sanctions in the different communities. It manages forest resources such as timber, animals, and almost all products in the PA. It is found in almost all communities in and around the Santchou PA.

Spatio-temporal dynamics of ECIs

Endogenous cultural institutions are not uniformly distributed in and around the Bakossi and Santchou PAs. In terms of the number of active institutions, some communities have two or more institutions active institutions, while others are characterized by sparsely spotted institutions (Fig. 3).

Despite their differences in structures, most of these ECI structures have undergone a series of changes. In the past, these institutional structures were broad and embodied several stakeholders or members. Presently, they are getting less effective, as respondents perceive a reduction in membership by about 40%; some have diverted to other religion such as Christianity and Muslim. For example, it was an obligation for every young man to be initiated into Muakum in the Bakossi PA in the past. Today, most youths consider it old and outdated and have refused to belong to this society. In the Santchou protected area, different ECIs play diverse roles in forest resource management. Temporal changes in ECIs are viewed from three phases: Prior to 1960, the management of the Bakossi protected area was shaped by the British indirect rule system; this implied that ECIs were valorized, as the British ruled mainly through their traditional institutions. However, in Santchou, the French direct rule prevailed—suggesting that the significant transformation of ECIs began during this period. However, in both sites, the practice of restricting women, children and youths from entering PAs (especially evil forests) was upheld. The sanctions ranged from material fines to ostracism and banishment. However, changes linked to the advancement of more formal, state rules led to conflicts and the progressive decline of ECIs between 1960 and 1990. While sanctions existed, they were not as effective as in the period prior to 1960. This was followed by a reduction in the number of ECI structures. After the 1990s, the spread of Christianity and other forces of globalization contributed to lessen the efficacy of these ECIs, albeit at varying proportions. For instance, some of these ECIs are active in some villages more than others (Fig. 3 and 4). For instance, the belief that pregnant women should not consume snakes, rat moles and pangolins is sparingly adhered to in some villages in the Santchou protected area.

From Fig. 4, ECIs are not equally distributed in the Santchou PAs. Some communities have numerous active institutions while others barely have a few. The spatial distribution of endogenous cultural institutions in this PA is highly attributed to variations in the level of enforcement. In communities where these institutions are less respected by their subjects, there are fewer institutions as compared to areas where these institutions are highly respected. Some communities transplanted very effective institutions from other areas with heavy sums of money and the performance of traditional rights, while others lack the opportunity to transplant these institutions such as Abashi, making institutions not to be uniformly distributed. The most influential, functioning and effective endogenous cultural institutions in communities in and around the Bakossi and the Santchou protected areas are Muakum and Abashi. It has been observed that most endogenous institutions such as Muakum, Ahon, Ndie (secret societies) and many others in the Bakossi PAs are very effective in the management of forest resources such as timber, bush animals and herbs. The degree of effectiveness of these institutions is attributed to the multiple rules (e.g. beliefs, sanctions, customs, and taboos) which help instill fear and prevent the random exploitation of forest resources in and around the PA. Notwithstanding, some endogenous cultural institutions such as Ngonie, Ewang and Muadelike are less effective in forest resource management as they have limited rules or processes enforcing them. Others such as Nzockton and Muawang are virtually dormant. The continuous interference and interception of endogenous cultural institutions in forest resource management by the state has prompted these endogenous cultural institutions to become less effective and some dormant in the management of forest resources in and around this protected area.

Implications for protected area management

During the period before 1960, the Bakossi forest was managed and controlled by the local or indogenous people through the application of rules or processes. The rules included; sanctions, beliefs, taboos, and customs which helped in reinforcing the different endogenous institutions to firmly manage the forest and it resources. For example, during the 1960s, it was believed that women, children and youths were not allowed to enter into the PA (especially evil forests) as this was considered to be the abode for deities (gods). Again, during the 1960s, defaulters of rules were sanctioned with fines using items such as a fowl and a 5L of palm wine depending on the nature of crime. Others were ex-communicated or banished. These rules were enforced by institutions such as Muakum and Ahon. In Santchou, beliefs such as the fact that pregnant women were not allowed to eat certain animals in the forest such as snakes, rat moles and pangolins were enforced; it was believed that these animals contribute to birth complications. There was equally a strong belief in totems, while taboos (e.g. the prohibition of tree cutting around deities) were firm and highly respected.

Between 1960 and 1990, the different management rules such as sanctions, taboos, beliefs, and customs reinforcing ECIs witnessed some changes. Due to population increase and the demand for agricultural space, women and children were forced to enter, cultivate and harvest forest resources in and around PAs. This introduced some level of tolerance with regards to the enforcement of endogenous cultural institutions. Sanctions were reinforced and fines gradually changed from fowl and 5littres of palm wine to crates of beer and a pig. In Santchou, endogenous cultural institutions witnessed slight changes in institutional structures and in the domains of management rules: In the past i.e. before 1960, the number of endogenous institutional structures were fewer than the present number of institutional structures. In the past, the communities did not have Abashi as an institution. It was in the 1990s that this institution was transplanted from Mamfe to communities in and around the Santchou PA. These institutional structures are constantly being modified.

In Bakossi, some of the endogenous cultural institutions became less effective in forest resource management in and around the PA. For instance, in the past, it was a taboo for women and children entering or harvesting any forest product or resource in reserved areas in PA especially around areas where deities (gods) were kept. This is hardly respected today. Also, the arrival and establishment of new religious believes such as Christianity and Islam has prompted changes of believes in and around the PA with implications on the land cover of the PA negatively. In the past, it was believed in and around the PA that men were superior to women. Therefore, it was a taboo to see women carrying out certain activities like hunting, trapping or go for any activities in the forest reserve. Endogenous cultural institutions are currently being pressurized by multiple forces including population growth, migration, and changes in income, among others. In Santchou these changes are a result of socio-political and economic drivers such as population increase, government intervention, increase in migrants and religion. The rate of changes witnessed between 1990 to 2020 have left a remarkable and pronounced imprint on the land cover of the PA. The domain changes of management rules include sanctions, beliefs, taboos and customs. Over time, the belief that pregnant women should not eat certain animals in the protected area such as snakes, rat moles and pangolins became less adhered to.

A respondent narrated as such:

in the past, traditional days such as country Sundays (Nkwauh) were highly respected and no one was permitted to enter the protected area for any activity in or out of his or her community or village. It was a taboo to go out on Nkwauh into the protected area.

This was corroborated by another respondent who mentioned that:

if anyone goes into the protected area on traditional days, something uncertain may happen to the person. This prevented people from going or carrying out activities in and around the protected area on traditional days.

Such beliefs still exist till date, although the degree to which it is respected is not the same as compared to the past. For example, people in and around the protected area were not permitted to leave their community to other communities for any activity on traditional days. Today, it is no longer the same as they sometimes move out today. In the past, there was a strong belief in totems by the local population; it was held that totems were made visible to almost everyone in and around the different communities. One of the respondents recounted that the forceful declaration of Santchou as a protected area by the state, angered the population. This has prevented them from exercising their totemic powers. From Table 5, it is observed that ECIs in Bakossi and Santchou have undergone a series of changes with some modified, others completely changed, and some newly created, while others have been abandoned. This is seen in the case of Bakossi and Santchou as changes in management rules differs (Table 5).

Information on Table 6 shows that different drivers are responsible for endogenous cultural institutional change in and around the different protected areas. These drivers vary per institution even though some institutions are driven by similar forces. It was a taboo for men, children, and women to practice any form of activity around the abode of deities in the past but presently, agricultural activities are practiced around these areas. This is attributed to population increase and in-migration. Changes in endogenous institutions and in the management rules governing forest resources in the Bakossi protected area has made the protected area vulnerable to high rates of exploitation and degradation of resources such as timber, firewood, medicinal plants and bush animals.

Discussion

Institutional change in complex socio-ecological systems continue to shape the behavior of appropriators (resource users). While some institutions remain intact, others have been largely transformed and/or abandoned. This makes it difficult to ascertain what is left of institutions—endogenous cultural institutions. Taking the case of two culturally distinct protected areas, this paper sought to (1) identify and categorize ECIs linked to protected area management in Bakossi and Santchou, (2) analyze their spatio-temporal dynamics and (3) discuss their implications for protected area management.

Regarding the identification and categorization of ECIs, the results indicate that in both study sites, male-dominated institutions exist, with a largely perennial nature. In parts of West Africa, studies showed that endogenous cultural institutions are largely male dominated (Osei-Tutu et al., 2014; Yeboah-Assiamah et al., 2019). The perennial attribute of endogenous cultural institutions does not necessarily imply effectiveness. For instance, some of the rules regarding the non-consumption of certain animals by pregnant women are perennial, though largely ineffective in terms of adherence. The former situation is linked to the increase in medical facilities and the growing signals of Christianity. These two forces have reshaped the belief of women who today increasingly consume some of the forbidden animals. This confirms the assertion by Kimengsi et al., (2021a, b, c) that we now have ‘old wines in new wineskins’ in terms of the institutional architecture of certain parts of Africa. Furthermore, with the presence of improved access to health services, even birth complications which were attributed to the consumption of such animals are now taken care of by the health institutions. Socio-demographic factors, including religion and modernization have shaped institutional compliance in many parts of SSA (Hersi & Kangalawe, 2016), including Ethiopia (Tesfaye et al., 2012) and Burkina Faso (Coulibaly-Lingani et al., 2009).

In addition to the above belief, the practice of totems which was community-wide is still perennial, but it has been reduced to household/individual levels. Although some institutions have a perennial status, they are actually a product of institutional transfer and transplant. For instance, the Abashi does not originate from the Santchou area. This institution was transplanted from Manyu Division in the South West Region (English speaking part of Cameroon) into Santchou. While the main reason for this transplant was not to regulate forest use, this highly feared institution which is less than four decades old in Santchou has installed itself as one of the key ECIs around the Santchou Protected area. Therefore, despite its seemingly endogenous and perennial nature today, it could be viewed as exogenous (albeit informal), based on its origin. This justifies earlier claims that institutions that existed in former British Cameroons (Mamfe being part) were more robust and perennial in nature, than those in other areas (Kimengsi & Balgah, 2021). The breakdown of ECIs (informal institutions) has been largely attributed to the importation and transplant of exogenous formal ones. This creates sub-optimal outcomes, as indicated in the literature on institutional bricolage in diverse parts of Asia (Haapal & White 2018; Steenbergen & Warren 2018), Africa (Cleaver, 2012; Friman, 2020; Kimengsi & Balgah, 2021; Sakketa, 2018) and Latin America (Faggin & Behagel 2018; Gebara 2019).

Institutional change can assume diverse patterns: Going by the endogenous—exogenous analytical lens, it is plausible to draw from our case that endogenous cultural institutions might actually have an exogenous undertone which must not be swept under the carpet. This finding provides new insights with regards to the fact that exogenous institutions could actually, with time, assume an endogenous character. However, conditions under which such transformations occur, especially in the spectrum of informal institutional arrangements need to be further clarified. This position is shared by Yeboah-Assiamah et al. (2017) who argued that both informal (endogenous) and formal (exogenous) institutions do not only catalyze resource governance, but are mutually reinforcing. It however deviates from the mainstream literature which holds that most of the endogenous cultural institutions have been weakened, broken down and/or transformed, largely by formal (exogenous) institutions (Chabwela & Haller, 2010; Buchenrieder & Balgah, 2013; Ensminger, 1997; Haller et al., 2018; Kimengsi & Balgah, 2021). What such positions fail to capture has to do with the exogenous nature of informal institutions—the case of Abashi in Santchou—which bears eloquent testimony of an exogenous informal institutions, now culturally embedded in Santchou—assuming an ECI attribute. It could equally be deduced that the most influential ECIs do not necessarily originate from the community. For instance, the most influential, functioning and effective endogenous cultural institution for communities around the Santchou protected area is Abashi. However, this institution was only borrowed from Manyu Division and transplanted into the community less than four decades ago. Today, based on its influence, it has the attribute of a perennial institution. On the contrary, historically embedded institutions such as Ngonie, Ewang and Muadelike generally exhibit ephemeral and intermittent characteristics, suggesting the claim that endogenous cultural institutions have been transformed and/or weakened in several parts of SSA (Ensminger, 1997; Haller et al., 2018). The finding is in contrast with those of Haller (2001) who linked the perennial nature of endogenous cultural institutions to the envisaged benefits derived from them by those who enforced these rules.

It was further observed in both protected areas that, although some of these institutions regulated the use of resources around protected areas, they were not initially set up for this purpose. For instance, the Mbumauku and Mboumagie focused on dispute settlement—including non-protected area linked disputes. However, with the potentials exhibited by these ECIs, it is plausible to infer that such institutions have the potential to be canalized to support present day protected area management, at a time when exogenous, centralized systems have proved to be inefficient. To Rahman et al. (2017), the management of natural resources for sustainability remains elusive if institutions do not directly address existing inter-institutional gaps between several institutions. This position does not seem tenable in the current study, as institutions which were crafted for other purposes, ended up effectively regulating resource use around protected areas.

Even within the same ethnic group, a relatively non-uniform pattern of distribution exists for ECIs. This could be linked to the differential effects of forces such as religion, migration and modernization. Although these are acknowledged stressors of ECI systems (Coulibaly-Lingani et al., 2009; Hersi & Kangalawe, 2016; Tesfaye et al., 2012), the extent to which each of these factors account for the non-uniform patterns in the distribution of active institutions remains a subject for further empirical investigation. Furthermore, most of these ECI structures have undergone a series of changes in terms of the membership and growing ineffectiveness. The latter is attributed to several forces, including the growing influence of Christianity and Islam. Due to the changing nature of institutions, sanctions have metamorphosed in several ways: for instance, in Bakossi, defaulters were sanctioned with fines using items such as a fowl and 5 L of palm wine depending on the nature of the crime, while others were ex-communicated or banished. In Santchou, beliefs such as the fact that pregnant women were not allowed to eat certain animals were still effective. These rules were believed to be spiritually-enforced, as women bled to death during child bearing. However, due to the increased access to medical facilities, such birth complications have been minimized. Over time, this belief has become relatively less effective. Kimengsi and Balgah (2021) reported that these changes are not only attributed to population increase, but are a subject of a ‘colonial hangover’. The authors argued that communities that were formerly shaped by British indirect rule, could still boast of some relatively intact endogenous cultural institutions, as opposed to those in former French parts, where the direct rule effect seemed to have weakened embedded structures. These account for the lukewarm attitude with regards to the respect of certain customs and beliefs on the one hand, and in the limited enforcement of sanctions. The current lethargy results in a more bricolaged institutional arrangement, as actors draw from diverse endogenous and exogenous provisions to navigate the resource access and use process around protected areas. This has been reported in several contexts across SSA (Cleaver, 2012; de Koning & Cleaver, 2012; Friman, 2020; Ingram et al., 2015; Sakketa, 2018).

Some of the key drivers linked to ECI change, as culled from the KIIs and FGDs include population growth, migration, religious influence, political transition and education, among others. In these, it could be summarized that institutional change is shaped by an interplay of resource use and management actors (Beunen & Patterson, 2019). While these forces seem tenable, a more quantitative study to ascertain to the extent to which each of these factors contribute to institutional change is required.

Conclusion

While endogenous cultural institutions (ECIs) have been subjected to significant breakdown/transformation, there is growing interest to analyse what is left—the ‘last vestiges’ of endogenous cultural institutions. This paper sought to provide empirical evidence from Cameroon—one of the most culturally diverse countries in SSA. Based on the empirical evidence derived, it is plausible to conclude as follows: Firstly, institutions that assume an endogenous cultural nature in some communities could potentially have an exogenous origin with a perennial nature. This suggests the need to carefully examine the source of ECIs in many parts of SSA. In a related dimension, some ECIs may assume ephemeral to intermittent nature, despite being culturally embedded in communities. Secondly, while present day ECIs regulate the use of natural resources around protected areas, they were not initially set up for this purpose. Thirdly, even within the same ethnic group, ECIs exhibit spatio-temporal variations in terms of their effectiveness. Although mapping such variations is the first step, further evidence (probably adopting complementary methods) on the differential forces which produce these variations are required. From a theoretical standpoint, the paper provides revealing insights on the exogenous nature of endogenous institutions, as well as on the perennial but ineffective nature of institutions. This contradicts previous institutional theoretical positions (e.g. Ostrom, 1990’s ‘enduring institutions’), as not all enduring institutions are effective. Furthermore, considering the call to leverage endogenous cultural institutions, the framing of Cameroon’s future forest policies demand the provision of answers to the following dilemmas: (1) what is the nature of Cameroon’s diverse endogenous cultural institutions—are they more exogenously or endogenously rooted? Do they exhibit attributes of ephemeral, intermittent or perennial institutions? Were such institutions designed with the intention to regulate forest resource use and management and/or could they potentially be adapted to do so? These questions, including a clear understanding of the differential levels of effectiveness and the determinants thereof, are required to effectively inform Cameroon’s forest policy revision. This article provides a useful scientific contribution to institutional change theory, by providing empirical evidence on the transformation of exogenously-sourced institutions into more endogenous and perennial ones. Furthermore, it provides new insights on the fact that transplanted institutions could become perennial.

Notes

The terms ephemeral, intermittent and perennial, are borrowed from the geographic classification of streams (Gomes et al., 2020). Ephemeral refers to short term stream movements (institutional arrangements), intermittent is analogous to medium term/seasonal streams (medium-term institutional arrangements), and perennial relates to streams that flow all through – analogous to more long-term, enduring institutions.

Ethnic fractionalization measures diversity as a steadily increasing function of the number of cultural groups in a country. Fractionalization indices range from 0 (when all individuals are members of the same cultural group) to 1 (when each individual belongs to his or her own group) (Drazanova, 2020).

Drawing from literature which holds that endogenous cultural institutions in SSA have been significantly broken down, transformed, and/or eroded by several forces ((Chabwela & Haller, 2010; Ensminger, 1997; Haller et al., 2018; Kimengsi & Balgah, 2021), we consider the remnants as the last vestiges.

References

ADB (African Development Bank). (2009). Cameroon, Diagnostic study for the modernisation of land and surveys sector. Yaounde Cameroon: Country Regional Department Centre.

Beunen, R., & Patterson, J. J. (2019). Analysing institutional change in environmental governance: Exploring the concept of ‘institutional work.’ Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(1), 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2016.1257423.

Chabwela, H. N., & Haller, T. (2010). Governance issues, potentials and failures of participative collective action in the Kafue Flats, Zambia. International Journal of the Commons, 4(2), 621–642. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.189.

Cleaver, F. (2012). Development through bricolage: Rethinking institutions for natural resource management. Routledge.

Coulibaly-Lingani, P., Tigabu, M., Savadogo, P., Oden, P.-C., & Ouadba, J.-M. (2009). Determinants of access to forest products in southern Burkina Faso. Forest Policy and Economics, 11(7), 516–524.

de Koning, J., & Cleaver, F. (2012). Institutional bricolage in community forestry: An agenda for future research. In B. J. M. Arts, S. van Bommel, M. A. F. Ros-Tonen, & G. M. Verschoor (Eds.), Forest people interfaces; Understanding community forestry and biocultural diversity (pp. 277–290). Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Drazanova, L. (2020). Introducing the historical index of ethnic fractionalization (HIEF) dataset: Accounting for longitudinal changes in ethnic diversity. Journal of Open Humanities Data, 6(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5334/johd.16.

Ensminger, J. (1997). Changing property rights: Reconciling formal and informal rights to land in Africa. In Drobak, J. N., & N. J. V. C (eds.) The frontiers of the new institutional economics (pp. 165–196). San Diego: Academic Press.

Estrella, G., & Marta, R. (2014). The use of visual methods for diagnosis and social intervention through a study of two towns in Spain and Cameroon. Portularia. Revista De Trabajo Social, 14, 3–14.

Ebua, V., Tamungang, S., Angwafo, T. E., & Fonkwo, S. (2013). Impact of livelihood improvement on the conservation of large mammals in the Bakossi landscape, South West Cameroon. Greener Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 3, 033–038. https://doi.org/10.15580/GJAS.2013.1.102712164

Faggin, J. M., & Behagel, J. H. (2018). Institutional bricolage of Sustainable Forest Management implementation in rural settlements in Caatinga biome, Brazil. International Journal of the Commons, 12(2), 275–299.

Fearon, J. D. (2003). Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 195–222.

Fokeng, M. R., & Meli, V. (2015). Modelling drivers of forest cover change in the Santchou Wildlife Reserve, West Cameroon using remote sensing and land use dynamic degree indexes. Canadian Journal of Tropical Geography Revue Canadienne De Géographie Tropicale, 2(2), 29–42.

Friman, J. (2020). Gendered woodcutting practices and institutional bricolage processes—the case of woodcutting permits in Burkina Faso. Forest Policy and Economics, 111, 102045.

Gebara, M. F. (2019). Understanding institutional bricolage: what drives behavior change towards sustainable land use in the Eastern Amazon? International Journal of the Commons, 13(1), 637–659.

Greif, A., & Mokyr, J. (2016). Cognitive rules, institutions, and economic growth: Douglass north and beyond. Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(1), 25–52.

Greif, A. (2006). Institutions and the path to the modern economy: Lessons from medieval trade. Cambridge University Press.

Greif, A., & Laitin, D. D. (2004). A theory of endogenous institutional change. American Political Science Review, 98(4), 633–652.

Gomes, P. I. A., Wai, O. W. H., & Dehini, G. K. (2020). Vegetation dynamics of ephemeral and perennial streams in mountainous headwater catchments. Journal of Mountain Science, 17, 1684–1695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-017-4640-4

Haller, T., Belsky, J. M., & Rist, S. (2018). The constitutionality approach: Conditions, opportunities, and challenges for bottom-up institution building. Human Ecology, 46(1), 1–2.

Haller, T. (2001). Rules which pay are going to stay: Indigenous institutions, sustainable resource use and land tenure among the Ouldeme and Platha, Mandara Mountains, Northern Cameroon. Bulletin de l'APAD, last visited: 29.01.2018 (available at: http://journals.openedition.org/apad/148).

Hersi, N. A., & Kangalawe, R. Y. (2016). Implication of participatory forest management on Duru-Haitemba and Ufiome Forest reserves and community livelihoods. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment, 8(8), 115–128.

Ingram, V., Ros-Tonen, M. A. F., & Dietz, T. (2015). A fine mess: Bricolaged forest governance in Cameroon. International Journal of the Commons, 9(1), 1–24.

Kaimowitz, D., & Angelsen, A. (1998). Economic models of tropical deforestation—a review. Center for International Forestry Research, Indonesia, 979–8764–17–X.

Kimengsi, J. N., & Balgah, R. A. (2017). Repositioning local institutions in natural resource management: Perspectives from Sub-Saharan Africa. Schmollers Jahrbuch Journal of Contextual Economics, 137(2017), 115–138.

Kimengsi, J. N., & Balgah, S. N. (2021). Colonial hangover and institutional bricolage processes in forest use practices in Cameroon. Forest Policy and Economics, 125, 102406.

Kimengsi, J. N., & Bhusal, P. (2021). Community forestry governance: Lessons for Cameroon from Nepal? Society and Natural Resources, forthcoming.

Kimengsi, J. N., Buchenrieder, G., Pretzsch, J., Balgah, R. A., Mallick, B., Haller, T., Huq, S. (2021a). Institutional jelling in socio-ecological systems: Towards a novel theoretical construct? Unpublished Manuscript

Kimengsi, J. N., Owusu, R., Djenontin, S. N. I., Pretzsch, J., Giessen, L., Buchenrieder, G., Pouliot, M., & Acosta, N. A. (2021b). What do we (not) know on institutions and forest management in sub-Saharan Africa? A sub-regional comparative review. Land use policy (Under review).

Kimengsi, J. N., Giessen, L., & Pretzsch, J. (2021c). Old wine into new wineskins? Forest-linked institutional change and policy implications in Cameroon, International Forest Policy Meeting (IFPM3). 17–18 March 2021, University Freiburg (Germany). https://ifpm3.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Kimengsi_Jude_Ndzifon-1-1.pdf

Kimengsi, J. N., Aung, P. S., Pretzsch, J., Haller, T., & Auch, E. (2019). Constitutionality and the co-management of protected areas: Reflections from Cameroon and Myanmar. International Journal of the Commons, 13(2), 1003–1020.

Manolache, S., Nita, A., Ciocanea, C. M., Popescu, V. D., & Rozylowicz, L. (2018). Power, influence and structure in Natura 2000 governance networks. A Comparative Analysis of Two Protected Areas in Romania, Journal of Environmental Management, 212(2018), 54–64.

Marcel, E. P. G., & Ajonina, U. P. (2021). Determinants of failures of local agricultural firms in Cameroon: The case of SODERIM, UGICAES and UGIRILCOPAM in the Mbo Plain (Cameroon). International Journal of Business and Economics Research. Special Issue: Microfinance and Local Development., 10(2), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijber.20211002.13

North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

Osei-Tutu, P. (2017). Taboos as informal institutions of local resource management in Ghana: Why they are complied with or not. Forest Policy and Economics, 85, 114–123.

Osei-Tutu, P., Pregernig, M., & Pokorny, B. (2014). Legitimacy of informal institutions in contemporary local forest management: Insights from Ghana. Biodiversity and Conservation, 23(14), 3587–3605.

Osei-Tutu, P., Pregernig, M., & Pokorny, B. (2015). Interactions between formal and informal institutions in community, private and state forest contexts in Ghana. Forest Policy and Economics, 54, 26–35.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Rahman, H., Ville, A., Song, A., Po, J., Berthet, E., Brammer, J., & Hickey, G. (2017). A framework for analyzing institutional gaps in natural resource governance. International Journal of the Commons, 11(2), 823–853.

Sakketa, T. G. (2018). Institutional bricolage as a new perspective to analyse institutions of communal irrigation: Implications towards meeting the water needs of the poor communities. World Development Perspectives, 9, 1–11.

Sone, E. M. (2016). Language and gender interaction in Bakossi proverbial discourse. California Linguistic Notes, 40(1), 40–50.

Tesfaye, Y., Roos, A., Campbell, B. J., & Bohlin, F. (2012). Factors associated with the performance of user groups in a participatory forest management around Dodola forest in the Bale mountains, Southern Ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies, 48(11), 1665–1682.

Yeboah-Assiamah, E., Muller, K., & Domfeh, K. A. (2017). Institutional assessment in natural resource governance: A conceptual overview. Forest Policy and Economics, 74, 1–12.

Yeboah-Assiamah, E., Muller, K., & Domfeh, K. A. (2019). Two sides of the same coin: Formal and informal institutional synergy in a case study of wildlife governance in Ghana. Society & Natural Resources, 32(12), 1364–1382.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Grant ID: F-010300-541-000-1170701.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. This research did not experiment with humans or animals. Prior informed consent of respondents was sought before the data collection process.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kimengsi, J.N., Abam, C.E. & Forje, G.W. Spatio-temporal analysis of the ‘last vestiges’ of endogenous cultural institutions: implications for Cameroon’s protected areas. GeoJournal 87, 4617–4634 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10517-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10517-z