Abstract

This paper aims to develop, through a literature analysis, a portrait of the functioning and practice of teacher thinking at government and university levels. Teacher thinking is defined as habits and strategies or the habit of thinking used to collect information, analyze, understand institution, reflect, solve problems, inform decisions, initiate action, and accumulate practical wisdom. Teachers develop the habit of accumulating practical wisdom to make good decisions for student learning. To cultivate thinking skills, governments can enact teacher professional standards and teacher education curricula. Field experience at the university level should also be designed to involve multiple teaching strategies and a coherent and consistent learning experience in different educational courses, which will help foster thinking habits to accumulate practical wisdom. Portfolio assessment, performance-based assessment, and teacher situational judgment tests can be used to assess teacher candidates’ thinking and cognition regarding teaching and learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In a society facing rapid technological development and an increasingly international economy, it is never clear how to prepare the young for future needs in a way that fosters their future well-being. Related to this endeavor, pre-service teacher education has to be designed to prepare teachers to adapt to the changing environment and to continually upgrade their teaching. The characteristics of the ideal teacher needed in future must be carefully considered. Ideal teachers have to control their own continued employability, professional knowledge and skills, and their ability to be developed as developability to undertake ongoing professional development to meet the future, yet unknown needs of their students. Thus, teachers have to commit themselves to continuous development of their teaching skills. The basis of developing a teacher’s employability and ability for development—may lie in the cultivation of teacher thinking.

According to Schön’s book The reflective practitioner (1983), the best professionals know more than they can articulate. To meet the challenges of their work, they depend less on formulas learnt at university than on the type of knowledge learnt in practice. This unarticulated knowledge is a manifestation of reflection-in-action as well as of a potential mechanism to be further cultivated in professionals. It is thus necessary to understand how reflection-in-action works in learning from practice and in the accumulation of teacher professional knowledge.

Another aspect of teacher thinking is the “implicit theories of teacher” proposed by Clark and Peterson (1986). The implicit theories operate from the assumption that a teacher’s cognitive and other behaviors are guided by their own personally held belief systems, values, and principles. Such theories, also known as teachers’ craft knowledge (Zeichner et al. 1987), implicit theory, or practical wisdom (Aristotle’s terms), describe a way of being concerned with one’s life and with the lives of others and all surroundings connected to one’s scope of practice. Practical wisdom is also called wisdom of practice by Shulman (2004), who proposes that a disposition or habit, which reveals the nature of the action while under deliberation, is the mode of bringing about the appropriation of that action. Whatever it is called, it roughly describes a type of individual knowledge that may not be articulated in words but ensconced in teachers’ beliefs or reflected in teachers’ behaviors. More specifically, Calderhead (1987) defines teacher thinking as the way in which knowledge is actively acquired and used by teachers and the circumstances affecting its acquisition and employment. An analysis of the terms mentioned about teacher thinking suggests that it refers to a process and the end result is practical wisdom.

In this paper, teacher thinking is the starting strategy or the habit of thinking for collecting information, reflecting, understanding, solving problems, making decisions, and accumulating practical wisdom. Because of the importance given to student learning and ensuring the quality for the future, teacher thinking has to be treated as a cornerstone for the cultivation of reflection, initiating action, and developing problem-solving skills in teachers. Teacher thinking is one of the key skills to develop during pre-service teacher education, along with professional teacher expert knowledge, as it enables teachers to perceive significant functions in their teaching work.

2 Views on teacher’s thinking

Clark and Lampert (1986) noted that teachers’ thinking affects how teachers absorb knowledge about the complexity of teaching, as well as their personal knowledge and methods of inquiry. First, an ideal teacher can make proper work decisions if they prioritize thinking. Teacher thinking is the foundation of teachers’ decision making, a crucial skill in a field with many competing requirements. A teacher’s work is centered on the clients, students, as well as other stakeholders, including parents, administrators, advisors, curriculum development agencies, and politicians, all of whom play a role in determining teachers’ work conditions. Teachers may encounter multiple conflicting expectations as well as those that conflict with their own beliefs (Shulman 2004).

Furthermore, a teacher’s classroom is a busy place. At any moment, teachers may have to manage multiple tasks—keeping the class working quietly, postponing or redirecting student’s requests for attention, and conducting particular activities in groups or as a class. Teachers may have to weigh the possible benefits of encouraging cooperative work (potentially greater student satisfaction) against the costs of more pre-lesson preparation, the risk of some students opting out and leaving others to do the work, and the additional demands on the teacher’s managerial skills. Thus, teacher preparation activities for the classroom have to be fast-paced. Furthermore, some serious decisions and difficult practices may look easy—in particular, moral/ethical or value-based decisions (Labaree 2000). Teachers have to apply their knowledge, especially their practical knowledge, to cope with the constant barrage of complex situations they find themselves confronted with.

Teacher thinking is used loosely to refer to various processes such as perception, reflection, problem solving, inquiring, and the manipulation of ideas (Calderhead 1987). In their work, teachers use a body of specialized knowledge on topics such as curriculum planning, teaching methods, subject matter, classroom management, and child behavior, together with other information gained through the experience of working with children in numerous contexts and with different materials. Scholars working in the field of teacher thinking have confirmed that teachers are constantly making decisions and drawing on a rich store of knowledge when they are engaged in planning and teaching (Wilson et al. 1987). Shulman (1975) considered teaching as clinical information and a cognitive process that includes perception, expectation, diagnostic judgment, prescription, and decision making. In order to make the right decisions, teachers need personal and professional knowledge of teaching and learning different topics. Teachers also obtain their personal and professional knowledge through the cognitive process of modifying their work to meet their students’ needs. These needs can only be discerned after interacting with students, giving them instruction, and experiencing the classroom dynamics (Ball and Forzani 2009).

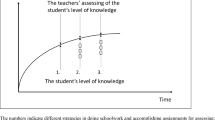

In classroom teaching, there is often little opportunity to reflect upon problems and to bring one’s knowledge to bear in the analysis and interpretation of classroom situations. Teachers must often react to situations immediately and intuitively. This raises the question of how to help teacher candidates to make the right decisions promptly. They must develop the habit of thinking early in their careers to foster their skills through regularly implementing practice and reflection. Through this process, teachers can develop more specialized knowledge and skills that can be applied to future situations.

The process of implementing the habit of thinking is accompanied by multiple thinking processes, not only about the initiation of the action itself but also about one’s existing practice. Teacher candidates are often inexperienced in self-criticism as well as in grasping constructive or imaginative ideas and in the implementation of those ideas. The responsibility of pre-service teacher education is to provide programs and mentors that address the role of teacher thinking and use methods of inquiry to study the conceptions, implicit theories, and judgment processes of teaching practice (Clark and Lampert 1986). This is especially important if teacher candidates come with incomplete and erroneous pre-conceptions about teaching and its complexities.

In summary, perspectives on teacher thinking in literature are as follows:

-

Teacher thinking has to produce action that changes or promotes students’ success and quality of life.

-

Teacher thinking is the starting point of the process for collecting, reflecting, reasoning, understanding, and accumulating practical wisdom.

-

The habit of teacher thinking ought to be a primary goal of pre-service teacher education.

-

The habit of teacher thinking is cultivated through practical experience and through deliberate application of theory to practice.

-

The habit of teacher thinking starts with guidance during pre-service teacher education and continues through in-service professional development.

-

Teacher thinking is a habit that a professional teacher must acquire.

If teaching necessarily involves uncertainty and managing dilemmas, then pre-service programs have to be designed to equip teachers with appropriate knowledge and wisdom to apply in any situation they may encounter.

3 Ways to cultivate teacher candidates’ thinking

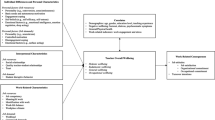

The ways to promote teacher candidates’ thinking can be divided into two levels: government and university levels.

3.1 The government level

Governments can incorporate teacher thinking into their national teaching standards. In England, Teachers’ Standards were released to replace the standards for Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) and the Core Professional Standards established by the Training and Development Agency for Schools, and the Code of Conduct and Practice established by the General Teaching Council for England. These standards outline the profile of ideal teachers in England that clearly represents thoughtful teachers who have up-to-date knowledge and skills, and a capacity for self-criticism, and who can anticipate what students need for academic achievement and well-being (Department for Education 2013).

A statement by the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP), which is the unified accrediting body for educator preparation in the US, lists a requirement among its teacher education standards that educators must ensure teacher candidates can “develop a deep understanding of the critical concept and principles of their discipline and are able to use discipline-specific practices flexibly to advance the learning of all students toward attainment” (CAEP 2013, p. 2). This deep understanding relies on the quality of teachers’ thinking. In addition, the Teaching Professional Standards formulated and enacted by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CCTC) and California Department of Education (CDE) in 1997 are designed to be used by teachers to prompt reflection about student learning and teaching practice (CCTC and CDE 1997). According to the function of standards, the content of the standards is an extension of a national consensus of ideal teacher features used to guide the direction of teacher education (Ingvarson and Rowe 2008; Stephenson 1999; Sykes and Plastrik 1993). Once teacher thinking has been incorporated into these standards, the cultivation of teacher thinking has to be put into the practice of teacher education.

3.2 The university level

When the cultivation of teacher thinking is outlined as the goal of teacher education, teacher education programs can adopt an ecological perspective of teacher education and can combine courses, teaching, practice, schools, and relevant staff into a systemic whole, as proposed by Wideen et al. (1998). According to this holistic perspective, there is a need during the pre-service formal training to support both theoretical training and personal support to help candidates internalize their teaching beliefs and to avoid a reality shock (Clark and Lampert 1986; Zeichner et al. 1987). Thus, the teacher education program should include two major elements: educational foundation courses and field experience.

3.3 The educational foundation courses

Teaching involves not only methodology but also philosophical and theoretical understanding. Teachers with deeper understanding are empowered to make thoughtful, informed decisions about instructional strategies and ways to support students’ learning (CCTC and CDE 1997). This goes back to the previously discussed idea that teachers who have the wisdom to be accountable for pupils’ attainment, progress, and outcomes can reach this state. Schwab (1964) pointed out that educational knowledge forms comprise theoretical disciplines, being concerned with with learners; practical disciplines, being concerned with choices, decisions, and actions based on deliberate decision; and productive disciplines, being concerned with the learners. Shulman (1987) categorized teacher knowledge bases into seven categories: content knowledge; general pedagogical knowledge; curriculum knowledge; pedagogical content knowledge; knowledge of learners and their characteristics; knowledge of educational contexts and of educational ends, purposes, and values; and knowledge of their philosophical and historical grounds. Darling-Hammond (2006) also indicated that the framework for understanding teaching and learning comprises knowledge of learners and their development in social contexts, knowledge of subject matter and curriculum goals, and knowledge of teaching. In addition, Turner-Bisset (1999) asserted that the knowledge bases for teaching are substantive subject knowledge; syntactic subject knowledge; beliefs about the subject, curriculum knowledge, general pedagogical knowledge; knowledge/models of teaching; knowledge of learners; knowledge of self; knowledge of educational contexts; knowledge of educational ends; and pedagogical content knowledge.

A comparison and analysis of the categories of knowledge for teaching listed by Schwab (1964), Shulman (1987), Darling-Hammond (2006), and Turner-Bisset (1999) show that the knowledge bases for teaching consist of “knowing why,” “knowing how,” and “knowing what.” “Knowing why” provides a foundational knowledge base for a teacher candidate’s thinking. For example, they will understand that the “beyond teaching” phenomena refers to a mix of social stratification or unfair social class and will be able to draw the proper conclusions to help students. As Day (2002) argued, to maintain good teaching, teachers must regularly revisit and review their teaching in terms of balancing not only the “what” and the “how” of their practice but also the “why” in terms of their core moral purpose to behave professionally and wisely. This reveals that the knowledge of “knowing why” for teacher candidates is as an important source of insight into thinking behind the phenomenon.

“Knowing how” means teacher candidates can design practice teaching innovation or promote student progress by practising effective teaching methods. “Knowing what” means teacher candidates can devise methods to approach the subject according to students’ developmental level on the basis of the structure or framework of subject content knowledge and their beliefs about the subject. The separate functions of “knowing why,” “knowing how,” and “knowing what” can form the foundation of the teacher education curricula for meeting professional teaching standards. According to Hollins (2011), the qualities that support learning to teach include collaboration, coherence, continuity, and consistency. Therefore, teacher thinking should involve standards that focus on building the knowledge base for teaching through case studies, inquiry, and guided observations to develop habits of mind and new ways of thinking to develop the wisdom of practice (Grossman et al. 2009).

Depending on a program’s quality of collaboration, coherence, continuity, and consistency, the components of “knowing why,” “knowing what,” and “knowing how” in university courses can help to foster teacher candidates’ thinking as a habit of teaching life. Therefore, teacher educators shape the common-sense goal of training candidates to practice thinking ahead by utilizing teacher strategies or assessment methods such as case studies, observations, videotaping, discussions, and using reflection sheets in their teaching. Furthermore, once the goal of a teacher education program has been formulated, connections can be made between the courses in the program. For instance, in teaching the sociology of education, case studies or case analysis by individual reports or group projects can be used to present and examine social mobility. Teacher candidates have to identify the case’s problem and the driving factors, analyze the solution, and assume a possible solution as if the case actually took place. For example, if cultural capital is an influential factor for social mobility in a case study, then a similar case can be part of an assignment on teaching material and methods. In the latter, teacher candidates could be requested to design teaching materials for supply to those with insufficient cultural capital.

3.4 The field experience

The trend in teacher education programs is to build teaching practice from educational theory. Teaching practice is as important for teachers as clinical experience is for doctors. The trend of searching for a more holistic approach to train effective teachers has been labeled as the realistic pedagogy of teacher education by Korthagen (2004), the practice-focused curriculum for learning teaching by Ball and Forzani (2009), and the holistic practice-based approach by Hollins (2011). In the process of teaching practice, teacher candidates can construct their understanding of the substantive relationship between teaching and learning through discourse, reasoning, decisions, and actions taken in interpreting and translating learners’ experiences and responses in authentic situations (Hollins 2011). In authentic situations, teacher candidates can use thinking and reasoning skills to formulate problems and to generate hypotheses, which Shulman (2004) indicates as the key to medical diagnostic success, and to enlarge their knowledge base for teaching and accumulate personal knowledge or wisdom by internalizing their individual cognitive structure (Tamir 1991). Teacher candidates identify differences between problems and attempt to reduce them through thinking and extended deliberate practice to acquire and refine their cognitive skills. This process is what Ericsson (2002) called cognitive mediation, Hollins (2011) called epistemic practice, and Fenstermacher (1986) referred to as the epistemology of practice.

Deliberate practice, purposefully and critically rehearsing certain kinds of performance, is important to the development of expertise (Ericsson 2002). Under the epistemology of practice, teacher candidates can retain cognitive control over detailed aspects of their performance at the highest levels of teaching, as shown by the results of research on the experts’ deliberate practice by Ericsson (2002) and by Ericsson and Charness (1994). The process of thinking, such as collecting information, identifying problems, making hypotheses, is designed to help teacher candidates connect theory and practice in order to understand the context of effective teaching and to cultivate and upgrade their professional teaching ability.

During pre-service teacher education in Taiwan, the teaching practicum is a good opportunity to put teacher candidates’ thought processes to deliberate practice in teaching situations. Teacher candidates go on their teaching practicum during their senior year of university. Requirements involve a week to a month in a teaching setting, minimum teaching of approximately 20 min, or teaching a class at secondary school, depending on what the professor has arranged for the teacher candidate. Some professors arrange tours to different schools in Taiwan. The teaching practicum component ranges between 40 and 260 h for teacher candidates. This intensive practicum is another opportunity to put thinking into practice. Due to the regulation of the Teacher Education Act in Taiwan, teacher candidates obtain their teacher qualification after taking a half-year practicum involving day-long teaching practice in school. Teacher candidates must experience four parts of school life: teaching practice, classroom affairs, administrative affairs, and professional development. Teacher candidates have to spend at least 960 h in school during their field exposure. This includes the hours of the actual practicum posting but is calculated totalling up the entire amount of hours spent in schools. In school, teacher candidates are guided by cooperative teachers who assist them in getting acquainted with school life, such as how to design coursework, arrange learning activities, prepare teaching materials, address students’ personal affairs, and communicate with parents by observing how these cooperative teachers do it.

4 Assessment methods for teacher thinking

Teacher thinking is among the professional standards that directs the content and implementation of teacher education courses. Thus, the way to find evidence of teacher candidate performance is as important as curriculum design. Authentic assessment can be used to assess teacher candidates’ thinking. As Darling-Hammond (1994), Linn et al. (1991), and Tellez (1996) indicated, authentic assessment or performance assessment involves real-world tasks and evaluations that emerge from context-sensitive understandings of pedagogical and personal principles underpinning the work of teaching. Such understanding must reflect criteria important for actual performance in a field of work. Methods of authentic assessment include portfolio and performance-based assessment that can be used in university courses or in the teaching practicum during pre-service and induction phases of the teacher education program. Teacher Situational Judgment Tests (TSJT) is another test for evaluating teacher candidates’ thinking, including reasoning, understanding, and decision-making abilities.

4.1 Portfolio assessment

The best-known portfolio assessment method is the Stanford Teacher Assessment Project (STAP), which was developed at Stanford University for use by the National Board of Professional Teaching Standards (Brookhart and Loadman 1995; Darling-Hammond 2001; Haertel 1987, 1991; Ingvarson and Rowe 2008; Tellez 1996). According to Shulman’s idea of teacher assessment (1988), STAP is a combination of methods, portfolios, direct observations, and better assessment measures that help develop a theoretical formulation around the centrality of content-specific pedagogy and the type of teacher understanding in pedagogical content knowledge. The portfolio is a tool for assessing a teacher or teacher candidate’s reflections on the richness and complexity of teaching and learning over time and allows examination of decisions that shape a teacher’s actions (Wolf 1991). It also benefits teacher candidates’ contextual sensitivity to teaching (Tellez 1996). A challenge of the portfolio collation is to ensure that teacher artifacts should not only be based on performance assessment criteria. These are useless for teachers’ professional development and are a waste of time for both the teachers who prepare them as it generates a lot of paperwork and for those who review them (Bird 1990). Instead, teacher candidates should have the opportunity for meaningful dialog and debate about education, teaching, and learning (Delandshere and Arens 2003). On the basis of the result of Wade and Yarbrough’s research recommendations (1996), portfolios used in teacher education programs should focus on teacher candidates’ initial understanding of the process and its purpose, encourage teacher candidates’ ownership and individual expression, provide some structural components to balance the open-ended nature of their contents, and involve an evaluation of the portfolio process and teacher candidates’ responses.

4.2 Performance-based assessment (PBA)

A recent research example of performance-based assessment (PBA) was developed by CCTC for assessing readiness for California’s Teaching Performance Expectation (CTPE), during pre-service teacher education following the Standards for the Teaching Profession (Hafner and Maxie 2006). The Performance Assessment of California Teachers (PACT), one of the three accepted programs by the California government, is designed around teaching events (TEs) that reflect teacher candidates’ planning, instruction, assessment, and reflection abilities in subject-specific areas, embedded signature assessment (ESA) that involves demonstrating teacher candidates’ ability to use research methods to collect information on course topics in the context of teaching and learning, and content area tasks (CATs) that display teacher candidates’ abilities to appropriately teach and assess student learning in various content areas (only for multiple subject candidates; College of Education and Teacher Education Program 2008/2009). The PACT focuses on two assessment strategies, while the TEs allow a global assessment of teaching knowledge and skills during student teaching in order to measure and promote candidates’ abilities to integrate their knowledge of content, students, and instructional context in making teaching decisions and stimulating teacher reflection on practice. The ESA is thus a formative assessment in the development of teacher candidates, providing useful feedback to teacher candidates and teacher educators (Pecheone and Chung 2006). The TEs and ESA provide candidates important opportunities for mentoring and self-reflection.

As previously mentioned, teacher candidates can experience actual school life through field study, teaching practicum courses, and, for example in Taiwan, the education practicum. Although teacher candidates have many opportunities to practice their skills, teacher candidates without any guidance can become frustrated by their errors as well as be confronted by a reality shock. Cooperative teachers and university professors as supervisors are needed to help teacher candidates learn how to teach. PBA using tasks modified from the PACT also provide teacher candidates with some independent guidance and with some support from cooperative teachers and supervisors. PBA was designed to correspond to the four parts of the teaching practicum (teaching practice, class affairs practice, administrative affairs practice, and professional development). First, PBA creates steps to follow such as learning modes, observation, planning, action, and reflection. Second, several issues or questions are raised to make teacher candidates notice key points about complex classroom situations. Third, these key points of awareness are also reviewed by standards for teacher education in the induction stages in Taiwan. PBA helps teacher candidates know what types of situations contain key practices to reflect upon and why. This reflection leads to the accumulation of practice and experience and the formation of implicit knowledge or practical wisdom.

4.3 Teacher situational judgment tests (TSJT)

Another approach to assessing teacher thinking, the TSJT, compensates for the shortcoming of traditional written exams for awarding teaching licenses. The TSJT, modified from the Situational Judgment Test (SJT), assesses teacher candidates’ thinking abilities and judgment performance. SJT is a measuring method and a tool for selecting employees based on tacit knowledge or practical know-how that usually not explicitly expressed or stated and that cannot be acquired through direct instruction. The purpose of the SJT is to identify individuals whose tacit knowledge indicates the potential for successful performance. Several research results (Chan and Schmitt 2002; McDaniel et al. 2007, 2001; O’Connell et al. 2007) suggested that the SJT is a cognitive ability test and a good and valid predictor of job performance. It typically presents applicants with task stimuli that mimic an actual job situation and elicit responses, which are interpreted as direct indicators of the how the applicant would handle the task if it were actually to occur in the workplace. Huang et al. (2013) identified five dimensions of teachers’ work in school in the TSJT: teaching, classroom management, learning counseling, relationships with teachers in school, and relationships with parents. Each dimension is related to the experts’ experience with construct validity. After the test, teacher candidates can identify their strengths and weaknesses in these five dimensions. This allows them to pay more attention to their weaker areas, and strengthen their skills independently during their pre-service teacher education or their teaching practicum.

5 Conclusion

As discussed in this paper, teacher thinking is a habit and a strategic process for collecting information, reflecting, understanding, solving problems, making decisions, initiating action, and accumulating practical wisdom. The habit of teacher thinking can be cultivated during pre-service teacher education and be continued during the induction phase and during in-service teacher education. To cultivate a thinking ability in teachers, governments can enact teacher professional standards that direct the process of teacher education. At the university level, “knowing why,” “knowing what,” and “knowing how” can be consistently and continuously incorporated into the teacher education curriculum and field experience through multiple teaching strategies for fostering habits of thinking and accumulating wisdom of practice. Furthermore, portfolio, the PBA, and the TSJT can be used not only to assess teacher candidates’ actual performance in teaching and learning but also to assess their thinking process and promote their knowledge of practice. From the policy formulation practice, teachers should have opportunities to think and reflect, and that this should become a habit so that they can accumulate practical wisdom. When teachers possess practical wisdom, they can make the right decisions to ensure better student learning outcomes and, consequently, a better future quality of life.

References

Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(5), 497–511.

Bird, T. (1990). The schoolteacher’s portfolio: An essay on possibilities. In J. Millman & L. Darling-Hammond (Eds.), The new handbook of teacher evaluation (pp. 216–228). Newbury Park, CA: Corwin.

Brookhart, S. M., & Loadman, W. E. (1995). Perspectives on teacher-assessment goals and their associated methods. In S. W. Soled (Ed.), Assessment, testing, and evaluation in teacher education (pp. 9–39). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Calderhead, J. (1987). Introduction. In J. Calderhead (Ed.), Exploring teachers’ thinking (pp. 1–19). London, UK: Cassell.

California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CCTC) & California Department of Education (CDE) (1997). California standards for the teaching profession. Scaramento, CA: Author. http://www.ctc.ca.gov.

Chan, D., & Schmitt, N. (2002). Situational judgment and job performance. Human Performance, 15(3), 233–254.

Clark, C., & Lampert, M. (1986). The study of teacher thinking: Implications for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 37(5), 27–31.

Clark, C. M., & Peterson, P. L. (1986). Teachers’ thought processes. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on reaching (3rd ed., pp. 255–296). New York, NY: Macmillan.

College of Education & Teacher Education Program. (2008/2009). Candidate handbook for the performance assessment for California teachers (PACT). College of Education. Retrieved from http://edweb.csus.edu/pact/assets/pact_handbook.pdf.

Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP). (2013). CAEP accreditation standards. Retrieved from http://caepnet.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/final_board_approved1.pdf.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1994). Performance-based assessment and educational equity. Harvard Educational Review, 64(1), 5–30.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2001). Teacher testing and the improvement of practice. Teaching Education, 12(1), 1–24.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 300–314.

Day, C. (2002). Developing teachers: The challenges of lifelong learning. Landon, UK: Routledge.

Delandshere, G., & Arens, S. A. (2003). Examining the quality of the evidence in preservice teacher portfolios. Journal of Teacher Education, 54(1), 57–73.

Department for Education (DfE). (2013). Teachers’ standards: Statutory guidance for school leaders, school staff and governing bodies. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/283198/Teachers__Standards.pdf.

Ericsson, K. A. (2002). Attaining excellence through deliberate practice: Insights from study of expert performance. In M. Ferrari (Ed.), The pursuit of excellence in education (pp. 21–55). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ericsson, K. A., & Charness, N. (1994). Expert performance: Its structure and acquisition. American Psychologist, 49(8), 725–747.

Fenstermacher, G. D. (1986). Philosophy of research on teaching: Three aspects. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 37–49). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Grossman, P., Compton, C., Igra, D., Ronfeldt, M., Shahan, E., & Williamson, P. (2009). Teaching practice: A cross-professional perspective. Teachers College Record, 111(9), 2055–2100. Retrieved from http://www.tcrecord.org/content.asp?contentid=15018.

Haertel, E. H. (1987). Toward a national board of teaching standards: The Stanford Teacher Assessment Project. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 6(1), 23–24.

Haertel, E. H. (1991). New forms of teacher assessment. Review of Research in Education, 17, 3–29.

Hafner, A. L., & Maxie, A. (2006). Looking at answers about reform: Findings from the SB2042 implementation study. Issues in Teacher Education, 15(1), 85–102.

Hollins, E. R. (2011). Teacher preparation for quality teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(4), 395–407.

Huang, J.-L., Chao, Z.-Y., & Sung, Y.-T. (2013). The theory and practice of construction for teacher situational judgment tests. In C.-J. Wu & J.-L. Huang (Eds.), Teacher education in i-cloud era (pp. 97–124). Taipei: Teacher Education Association. (in Chinese).

Ingvarson, L., & Rowe, K. (2008). Conceptualising and evaluating teacher quality: Substantive and methodological issues. Australian Journal of Education, 52(1), 5–35.

Korthagen, F. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: Towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(1), 77–97.

Labaree, D. F. (2000). On the nature of teaching and teacher education: Difficult practices that look easy. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 228–233.

Linn, R. L., Baker, E. L., & Dunbar, S. B. (1991). Complex, performance-based assessment: Expectations and validation criteria. Educational Researcher, 20(8), 15–21.

McDaniel, M. A., Hartman, N. S., Whetzel, D. L., & Grubb, W. L, I. I. I. (2007). Situational judgment tests, response instructions, and validity: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 60(1), 63–91.

McDaniel, M. A., Morgeson, F. P., Finnegan, E. B., Campion, M. A., & Braverman, E. P. (2001). Use of situational judgment tests to predict job performance: A clarification of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4), 730–740.

O’Connell, M. S., Hartman, N. S., McDaniel, M. A., Grubb, W. L, I. I. I., & Lawrence, A. (2007). Incremental validity of situational judgment tests for task and contextual job performance. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 15(1), 19–29.

Pecheone, R. L., & Chung, R. R. (2006). Evidence in teacher education: The performance assessment for California teacher (PACT). Journal of Teacher Education, 57(1), 22–36.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Schwab, J. J. (1964). Structure of the disciplines: Meanings and significances. In G. W. Ford & L. Pugno (Eds.), The structure of knowledge and the curriculum (pp. 1–30). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Shulman, L. S. (1975). Teaching as clinical information processing. In N. L. Gage (Ed.), NIE Conference on studies in teaching (Panel 6) (p. 49). Washington, DC: National Institute of Education, Singapore.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–21.

Shulman, L. S. (1988). A union of insufficiencies: Strategies for teacher assessment in a period of education reform. Educational Leadership, 46(3), 36–41.

Shulman, L. S. (2004). The wisdom of practice: Managing complexity in medicine and teaching. In S. M. Wilson (Ed.), The wisdom of practice: Essays on teaching, learning, and learning to teach (pp. 251–271). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Stephenson, J. (1999). Evaluation of teacher education in England and Wales. TNTEE Publications, 2(2), 191–201. Retrieved from http://tntee.umu.se/publications/v2n2/pdf/20England2.pdf.

Sykes, G., & Plastrik, P. (1993). Standard setting as educational reform: Trends and issues paper No. 8. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Teacher Education and American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education.

Tamir, P. (1991). Professional and personal knowledge of teachers and teacher educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 7(3), 263–268.

Tellez, K. (1996). Authentic assessment. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 704–721). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Turner-Bisset, R. (1999). The knowledge bases of the expert teacher. British Educational Research Journal, 25(1), 39–55.

Wade, R. C., & Yarbrough, D. B. (1996). Portfolios: A tool for reflective thinking in teacher education? Teaching and Teacher Education, 12(1), 63–79.

Wideen, M., Mayer-Smith, J., & Moon, B. (1998). A critical analysis of the research on learning to teach: Making the case for an ecological perspective on inquiry. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 130–178.

Wilson, S. M., Shulman, L. S., & Richert, E. R. (1987). “150 different ways” of knowing: Representations of knowledge in teaching. In J. Calderhead (Ed.), Exploring teachers’ thinking (pp. 104–124). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Wolf, K. (1991). The schoolteacher’s portfolio: Issues in design, implementation, and evaluation. Phi Delta Kappan, 73(2), 129–136.

Zeichner, K. M., Tabachnick, B. R., & Densmore, K. (1987). Individual, institutional, and cultural influences on the development of teachers’ craft knowledge. In J. Calderhead (Ed.), Exploring teachers’ thinking (pp. 21–59). London, UK: Cassell.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, JL. Cultivating teacher thinking: ideas and practice. Educ Res Policy Prac 14, 247–257 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-015-9184-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-015-9184-1