Abstract

Although the concept of Circular Economy (CE) has become popular in recent years, the transition towards a CE system requires a change in consumers’ behaviour. However, there is still limited knowledge of consumers’ efforts in CE initiatives. The present paper aims to analyse and compare consumers’ behaviour towards circular approaches and compare the results on items like generation and demographics. 495 answers were collected through a questionnaire from 3 countries (Albania, Poland, and Portugal). Data collected was analysed mainly through a Crosstabs analysis to identify associations or different behaviours regarding nationality, gender, generation, education, and place of residence. From the paper’s findings, we can emphasise that residents of EU countries seem to be more aware of the concept of circular economy. However, price is still a very important factor for EU residents when it comes to deciding on a greener purchase. Albanians (non-EU residents) tend to take a more linear approach when it comes to purchasing a new product regardless of its cost. Regarding the Digital Product Passport, a tool proposed by the European Commission through its Circular Economy Action Plan, non-EU residents have a better understanding of the concept. This tool seems to be more relevant for Millennials and Generation X. Generation Z, i.e., the tech generation, does not show an overwhelming propensity for technological options, such as online buying and digital technologies for a greener society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The concept of circular economy (CE) has gained significant attention in recent years as a potential solution to address the growing environmental and economic challenges faced by our society (Chen & Dagestani, 2023; Fatimah et al., 2023; Meili & Stucki, 2023). The European Green Deal (European Commission, 2019), which aims to make Europe climate-neutral by 2050, through objectives such as reducing waste, promoting resource efficiency, and fostering a sustainable economy has put the CE at the centre of its strategy. But are the institution’s efforts and rules towards CE being reflected in the concerns and behaviour of Europeans? A CE aims to create closed-loop systems where resources are kept in use for as long as possible, waste is minimized, and value is maximized. This requires companies to rethink their supply chains and business models but also raise customers’ awareness of this need to change the paradigm of consumption. In other words, it requires a broad alliance of stakeholders (Jabbour et al., 2019; Kirchherr et al., 2023). Along with the concept of CE, the concept of circular business models has gained significant attention in recent years because of its potential to address the growing environmental and economic challenges faced by our society (Bocken & Konietzko, 2022; Roci & Rashid, 2023). At the same time, they are an essential component of a CE, as they help to promote the reuse and recycling of products and materials, thereby reducing waste (Bocken et al., 2022) and generating new revenue streams for companies (Kanzari et al., 2022; Roci & Rashid, 2023). However, the successful implementation of circular business models requires commitment from both companies and consumers. As mentioned by Lazarevic and Valve, (2017) are consumers ready to change their role from consumers (owners) to users?.

Consumers might be passive recipients of goods and services in a linear economy, where products are designed to be used and then discarded, but in a CE they (we) may become active participants who contribute to the circular flow of resources by choosing sustainable products, extending the life of products, and returning products at the end of their life for reuse, repair, or recycling (Shevchenko et al., 2023). By purchasing products made from recycled materials, consumers can create a demand for recycled content, thereby increasing the demand for recycled materials and reducing the need for virgin materials (Stangherlin et al., 2023). Consumers can also choose durable and repairable products, which can extend the product's life and reduce waste (Gue et al., 2020). However, the repair culture depends on several stakeholders namely those normally identified as the triple helix stakeholders (industry (producers), Universities (all the educational system) and Government (namely local governments) (Korsunova et al., 2023). They may also choose to participate in sharing and collaborative consumption models, such as car-sharing and tool-sharing, which can reduce the need for individual ownership and promote the more efficient use of resources (Eckhardt et al., 2019; Lazarevic & Valve, 2017). The second-hand market can also be an option. If this market is quite popular for expensive goods, such as houses or cars, it can also work in less expensive products such as cloth (Persson & Hinton, 2023). But how committed are consumers to the CE? Considering the efforts developed by the European Commission at the environmental level are those citizens aware and committed to the issue? Along with other objectives, to be presented later on, it is aimed with this paper to explore the knowledge and behaviours of EU residents (from Poland and Portugal) and compare the results with a non-EU country (Albania). Considering consumers as end users and market drivers, it might be necessary to rethink not only business models and supply chains but also how to reshape consumer mindsets and behaviours (Stewart & Niero, 2018).

Although many companies have already been committed to adopting circular business models and implementing sustainable practices, the transition to a CE is not without challenges, such as changing consumer behaviour, product design, and supply chain management (Paparella et al., 2023; Shevchenko et al., 2023; Tunn et al., 2019). In this article, the focus is on consumer issues. Profitable circular business models may appear from the demand side. So, it is crucial to approach the demand-side perspective to define policies, strategies and actions that support the necessary shift towards a CE.

Understanding how consumers perceive and engage with circularity becomes crucial for the successful implementation of CE strategies (Patwa et al., 2021). Even recognizing the existence of studies in this field (to be developed in the next section) the gaps in understanding consumer behaviours and perceptions concerning circularity still exist because the identified studies target different issues under different environments. The need for development of studies in this area is identified by authors such as Bachmann and Jodlbauer, (2023), Cano et al. (2023) or (Kirchherr et al., 2023). Consumers cannot be considered passive buyers, on the contrary, they might be seen as co-creators, both in linear and circular business. For instance, Cano et al. (2023) studied the consumer perspective on sustainable business modes of e-marketplaces. They found out, that in general, younger, and more educated people are more engaged in digital businesses. The results suggest that the environmental dimension (against social and economic dimensions) is the one that has the most significant influence on the development of sustainable business models. However, consumers also point to factors such as price, timesaving, and diversity as the main reasons to use these platforms. So, we can ask if the environmental issue is a real concern for consumers. Regarding the acquisition of refurbished smartphones, Bigliardi et al. (2022) found that psychological factors, such as green perceived value and environmental knowledge, are the most powerful predictors of green purchase intention. On the other hand, the environmental concern seems not to influence consumer decisions.

The studies up to now mentioned reflect some green concerns from the consumer perspective, but other researchers, such as Zhong et al. (2022) suggest that some customers are not even committed to recycling practices, and others simply reject circular products (Stangherlin et al., 2023) or did not developed their greening preferences (Rizos et al., 2016).

The results from different studies pointing in different directions lead to the identification of a gap in consumer analysis in terms of circularity knowledge and decisions. This gap was also identified in other studies (Kutaula et al., 2022; Paparella et al., 2023; Shevchenko et al., 2023; Vidal-Ayuso et al., 2023) and led to the present research aiming at identifying consumer knowledge concerning CE concepts and some of their decisions regarding linear or circular behaviours. As argued by Vidal-Ayuso et al., (2023) consumers’ attitudes and knowledge are the most influential elements in the consumer’s buying decision-making process. Even with some studies aimed at consumers, their role is still an understudied topic (Shi et al., 2022; Stewart & Niero, 2018; Szilagyi et al., 2022). The literature essentially explores product lifespan from the perspective of product design or manufacturing practices, in the application of circular practices in the organizational and industrial sectors.

This research endeavours to analyse consumer knowledge and behaviours related to the CE. However, this can be considered preliminary research focusing on three countries, at different stages of their EU membership: Portugal (member since 1986), Poland (member since 2004) and Albania (a candidate country). It aims to identify different attitudes and knowledge about CE among these countries' residents. According to the results, further studies in terms of questions, respondents and new countries might be developed in order to get a clear understanding of consumers and their commitment to the CE as a tool to achieve the European Green Deal.

In this exploratory work, our focus is on the customers’ side, aiming to understand how consumers, in a very simple way, conceptualise the CE, i.e., to analyse the concept of CE from the consumer’s perspective. This concern with the perspective of demand-side occurs because we believe, such as Shi et al. (2022), that consumption behaviour directly affects the product lifespan, and sustainability goals contingent on consumption cannot be accomplished without consumers’ involvement. Summing up, the purpose of this article is to understand how familiar, concerned and committed are consumers towards CE, and to look for different results according to the “segments” of consumers, such as gender, generation, nationality, or education.

For that, a questionnaire was developed and applied in the three previously mentioned countries: Albania, Poland, and Portugal. With the data collected, it was possible to identify some attitudes, knowledge, and circular practices as well as to compare them among countries, places of living, gender, generation, and education. Another goal is the identification of differences between EU countries Members (Poland and Portugal) and non-EU (in this case, Albania).

Therefore, the objectives of this paper are (1) To contribute to the literature by identifying factors that may influence consumers' perceived knowledge about CE; (2) To identify factors that may affect consumers’ behaviour towards CE. These objectives will be broken into different research questions (RQ) presented as follows:

(1) To contribute to the literature by identifying factors that may influence their perceived knowledge of CE.

Do the different variables under research influence the precepted knowledge about CE?

Do the different variables under research influence Digital Product Passport interest and knowledge?

(2) To identify factors that may influence consumers' behaviour toward CE.

Do the different variables under research influence second-hand purchases?

Does nationality influence linear or circular buying under different price levels?

What are the main reasons to buy second-hand products?

Where are customers acquiring second-hand products?

By answering these RQ we may also have an overview of consumer knowledge and behaviour by different segments, such as nationality, place of residence, gender, generation, and education. This overview may allow us to identify some managerial and practical implications regarding the establishment and development of circular business models, mainly focusing on the consumers’ perspective. Those results will be developed in the discussion and conclusion sections.

In essence, this study aims to bridge the divide in consumer analysis within the realm of CE concepts. By exploring the consumers’ role and understanding their attitudes, knowledge, and practices, this research aims to not only contribute to the existing literature but also offer practical implications for implementing and nurturing circular business models in today’s economic landscape.

To accomplish the paper’s goals, it will be structured as follows. Section 2 provides a brief overview of the CE and some related concepts highlighting the role given to consumers in the circularity mission. In this section, some relevance is given to the Digital Product Passport (DPP) because of the expected impact it might have on the demand and supply side. After the literature review, Sect. 3 focuses on the methodological approach. Then, Sect. 4 presents the main results, the data analysis, and the findings of this research work. The last section is dedicated to conclusions, research limitations, and directions for future work.

2 Literature review

Even being considered one of the current megatrends, sustainability has been reported for a long time as a real concern for mankind. In the book Limits to Growth (Meadows et al., 1972) the authors argued that the earth’s interlocking resources probably could not support the rates of economic and population growth, seen at that time, much beyond the year 2100.

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development published a report entitled «Our Common Future», or the «Brundtland Report». It developed guiding principles for sustainable development as it is generally understood today (United Nations, 1987). Over the years several books and papers have been mentioning topics such as sustainable development, sustainable development goals (United Nations, 2015), sustainability or CE. The conclusions are all aligned: The planet has no resources to support our continuous growth.

One of the strategies that have been promoted to save the planet is the development of CE practices both at the producer and consumer levels (Ambaye et al., 2023; Carissimi et al., 2023). “A circular economy is an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013). There are several different approaches to CE (Kirchherr et al., 2017, 2023). The one from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation is just one example, but in general, they are related to the design of products and their environmental impact (Sonego et al., 2022). In other words, CE might be defined as a combination of factors to reduce, reuse, and recycle activities and/or materials (Forastero, 2023). It might be important highlight that even focused on the products design and environmental impact (producers’ perspective) the combination of factors identified by Forastero, are also relevant from the consumer’s perspective. In fact, producers might have circular concerns when designing their products, but at the end they need to sell them. So, they need a target that are the potential buyers, or in other words, consumers. “Responsible consumer is a part of the "circle" and without such a consumer, it is impossible to bring into life the functional circular economy” (Maťová et al., 2019).

The concept and the implementation of CE imply a strong collaboration among many actors, governments, producers, retailers, and consumers (Korsunova et al., 2023; Reich et al., 2023). This multi-layer approach is presented in the Circular Economy Action Plan (EC, 2020), from the European Commission. This plan is just one of the tools for the larger goal which is the European Green Deal (European Commission, 2019), which aims to make Europe climate-neutral by 2050. To reach that goal several measures have been taken by the European Commission being one of the most relevant targeting recycling practices (De Pascale et al., 2023). The closed-loop systems where resources are kept in use for as long as possible require the engagement of several stakeholders, and consumers are relevant (Vidal-Ayuso et al., 2023).

The engagement with CE may arise from different factors, but information and knowledge are common words associated with consumer circular behaviour (Bigliardi et al., 2022; Vidal-Ayuso et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020). According to (Maťová et al., 2019) to get consumers acting consciously they must be aware of environmental issues. These authors analysed the consumer perspective to identify the responsible consumer in the context of CE. Based on the 6R framework (Jawahir & Bradley, 2016), framework that evolved to the 10R (Reike et al., 2018), they were able to find two groups of consumers the conventional consumers (those following the original R concepts—Reduce, Reuse and Recycle) and the conscious consumers, that expressed more environmentally friendly attitudes (Recover, Redesign, Remanufacturing through other Rs more consumer oriented Rethink/Reinvent, Replace/Rebuy). These results reinforce the division among consumers that not all of them are at the same level of awareness. While someare aware of the environmental impact of their consumption choices and are already demanding more sustainable products and services. others are not even committed to recycling practices (Zhong et al., 2022). The behaviour is also conditioned by geographical cultures and levels of development (Hu et al., 2022). This diversity is not new, even not being a single product analysis, one can say that the demand for circular products (and consequently the existence and development of circular business models) may just follow the classic product life cycle. The question is at which stage are we? Like marketing in a linear economy, the success of circular business models also depends on the ability of companies to effectively communicate the benefits of circularity to consumers.

Consumers’ knowledge and decisions on circularity encompass their awareness and understanding of the principles of a CE, as well as their choices and behaviours related to sustainable consumption, product lifecycles, and waste management (Korsunova et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020). This topic holds significant importance as it sheds light on the factors influencing consumers' adoption of circular practices and provides insights into strategies for promoting sustainable consumption patterns.

Consumers’ knowledge plays a fundamental role in driving behaviour change towards circularity (Korsunova et al., 2023; Paparella et al., 2023; Shevchenko et al., 2023). When informed about the benefits of CE, such as reduced resource depletion, minimized waste generation, and increased product longevity, they are more likely to make conscious decisions aligned with circular principles (European Environment Agency, 2022). Understanding consumers’ awareness and knowledge gaps surrounding circularity can help identify areas for targeted education and awareness campaigns to enhance consumer engagement. Knowledge is intrinsically connected with education, and several authors present a relation between CE practices engagement and education (Koval et al., 2023); (Chad, 2023). The research that considers education as a key element to induce circular attitudes and behaviours, argue that education is crucial no matter its level. Some argue that circular awareness should be taught from primary school onwards (Tiippana-Usvasalo et al., 2023), while others defend their importance and sometimes absence in secondary education (Haase et al., 2024). The university level is also frequently mentioned and is often a variable to pay attention to because it presents impacts in the individual (consumer) behaviours (Matei et al., 2023; Mendoza et al., 2019).

This brief overview supports the research question that aims to identify the factors that influence the knowledge that consumers assume to hold about the CE concept. To have consumers engaged with CE, they must be informed (or educated) about it. It also supports the relevance of the education variable.

Consumer decisions on circularity encompass a range of behaviours, including product selection, use, maintenance, and end-of-life disposal. Factors such as product labelling, information accessibility, affordability, convenience, and perceived value influence consumers’ choices (Korsunova et al., 2023). Additionally, cultural norms, social influence, and personal attitudes towards sustainability play a vital role in shaping consumer decisions regarding circularity.

According to Paparella et al. (2023), the transition towards a CE system requires a change in consumers’ behaviour. However, there is still limited knowledge of consumers’ efforts in CE initiatives. Arranz and Arroyabe (2023) argue that the engagement of consumers in CE is not yet clear due to cultural barriers or lack of consumer acceptance that create certain inertia that can hinder the policies of institutions. But there are some clues in terms of consumer behaviour that were already identified: Consumer effort (that may compromise the success of circular business initiatives) (Guyader et al., 2022; Paparella et al., 2023; Tunn et al., 2019) and intention-behaviour gap (when the walk does not match the talk) (Carrington et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2021; Shaw et al., 2016). In the literature, it is possible to find different approaches. Among many other reasons price (Grafström & Aasma, 2021; Wang et al., 2019), and institutional and cultural issues (Grafström & Aasma, 2021; Hu et al., 2022) are appointed as CE motivators. If price as in the linear economy is an important factor for consumer decision-making, will other factors influence it as well? Combining the issue of prices with other factors such as nationality (mostly to understand if there are differences between EU and non-EU residents, because of the strategies that the European Commission have been implementing, under the second paper objective, we aim to explore whether nationality may influence a linear or a circular purchase pattern.

Other approaches defend that consumers are changing their behaviour. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2013), “a new generation of customers seem prepared to prefer access over ownership. This can be seen in the increase of shared cars, machinery, and even articles of daily use. In a related vein, social networks have increased the levels of transparency and consumers’ ability to advocate responsible products and business practices. Circular business design is now poised to move from the sidelines and into the mainstream. The mushrooming of new and more circular business propositions—from biodegradable textiles to utility computing—confirms that momentum.”

These new generations, according to Drugdova & Musova, (2020) are generations Z and Y (the latter in our research are designed as Millennials). Other studies analysing the intentions of younger generations towards CE found that younger generations seem to be aware of this need (Lakatos et al., 2018), in some cases the results point a higher degree of openness in what concerns behavioural changes towards a more circular attitude (Kowalska et al., 2020; Mykkänen & Repo, 2021; Neves & Marques, 2022).

According to Shevchenko et al. (2023), the operationalization of CE strategies requires the involvement of the consumers, namely in the acquisition, use, and disposal of products and services. However, according to the same authors, the inclusion of sustainable and circular practices in consumers is complex and can be said to be still at an early stage. For instance, Korsunova et al. (2023) argue that in Finland, consumers tend to perceive their participation in CE primarily through recycling and buying second-hand products. In Germany, regarding the apparel industry Wiederhold and Martinez (2018) found that price, availability, knowledge, transparency, image, inertia, and consumption habits were the main barriers to the consumption of sustainable fashion. In China, a study about the purchase of remanufactured products (Wong & Zeng, 2015), showed that price overlaps with quality factors. Another study (Bigliardi et al., 2022) also tried to identify the reasons for buying refurbished products, in this case, smartphones. This study was performed among a sample of technologically educated consumers and it was found that the most relevant factors to decide for a green buy (refurbished smartphones) were psychological factors, such as green perceived value and environmental knowledge. In this case, neither price nor quality. With the same concerns about consumer behaviour, Sharma and Foropon (2019) presented a study that aims to examine green consumption in India through the lenses of customers’ environmental concerns vs. other drivers for green purchases, revealing the importance of product attributes in the decision-making process of green purchasers.

This brief literature overview leads us to reflect on the diversity of variables that might influence consumer decisions about green or circular purchases. Quite frequently people are adopting circular behaviours but not for the environmental reason, issues like price or quality are more relevant than the green concern. So, reaching circularity through consumers may require the adoption of different strategies according to factors such as products, geographical location, or education levels. Some authors, such as Shang et al. (2022) or Arranz and Arroyabe (2023) argue that circularity might be easily reached if supported by regulation. However, even in terms of regulation, there is no consensus, while some argue that regulation should target consumers’ demand for circular products (Arranz & Arroyabe, 2023), others argue in favour of regulation aiming at producers (Maher et al., 2023; Pazienza & De Lucia, 2020; Stahel, 2013) or even production and consumption together as the Circular Economy Action Plan (EC, 2020), or the European Union Directive 2019/904 on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment.Footnote 1 To better understand the role of consumer, along with an analysis of their self-perception about the concept of CE (the first objective of the present research), we will also explore their behaviour mostly in terms of second-hand purchases. Those products might be acquired from a consumer-to-consumer perspective and might be refurbished or remanufactured. They can also be purchased from profit or non-profit business models (Persson & Hinton, 2023). Independently from the type of acquisition of those products, under the second objective of this paper, three questions were formulated to better understand consumer behaviour concerning the second-hand market, allowing the products’ time-life extension.

In regard to second-hand shops, different studies point to different results. The location, culture and economic factors must be taken into consideration when analysing this market, that for some can be defined as circular, but for others is the best economic option. For instance, in a study about textile second-hand purchases in Sri Lanka, Geegamage et al. (2023) found that second-hand buyers presented reasons for those buying as price-consciousness, consciousness on emotional bonds, comfortability consciousness, quality and brand consciousness and social and environmental consciousness. In a different location, in this case in a European country (Germany) Wilts et al., (2021) found barriers such as uncertainties about the reliability of the buyer or the quality of the product hinder the transition into sustainable consumption contributing to resource conservation and climate change mitigation, as well as contributing to a more economic rational decision. Different options for second-hand markets like specialized stores or web platforms are getting available for consumers (Calaza et al., 2023; Virgens et al., 2023; Yeap et al., 2022) however, this market share is very low when compared with new products markets. Even being a long existent market (Meneghin, 2022) some authors still identify the second-hand market as an emerging trend (D’Adamo et al., 2022).

Along with the circularity trend, another is going on: digitalization. Both are reshaping business models and consumption of goods and services (Ghoreishi et al., 2022; Sehnem et al., 2021). Digitalization is enabling new forms of circularity, such as sharing, swapping, renting, and rating which are transforming traditional business models across various sectors, including manufacturing, retail, and services (Agnusdei et al., 2023; Piscicelli, 2023; Trevisan et al., 2023). The development of digital options may also increase, for instance, second-hand deals, by developing dedicated platforms (Charnley et al., 2022; Yeap et al., 2022). However, there is still a limited understanding of the factors that influence the adoption and implementation of digital circular business models in different contexts and the potential impact on business performance and sustainability (Roci & Rashid, 2023).

From the producers’ and political sides, some tools like the digital product passport (DPP) are being developed (King et al., 2023). This tool, in particular, is expected to provide a digital record of a product’s environmental and social impact, as well as information about the product’s composition, origin, repair and end-of-life options. It is also another strategy defined by the European Commission to foster circularity (EC, 2020). By providing consumers with this information, DPPs aim to contribute to a more informed consumer, particularly at the level of (1) Transparency (enabling consumers to make informed decisions about the products they buy by providing transparent information about the product’s environmental and social impact); (2) Accountability (hold companies accountable for the environmental and social impact of their products); (3) Traceability (provide information about the origin and journey of a product, including the materials used and the manufacturing process); (4) Information about the possibilities to extend product lifespan (provide information about repair and recycling options for a product, enabling consumers to extend the lifespan of the product and reduce waste). DPP can empower consumers to make more sustainable choices and hold companies accountable for their environmental and social impact. As argued by Ospital et al. (2023) the discussion about transparency is still in its infancy, but solutions such as DPP might be interesting both in the economic perspective, but also fostering trust between supplier and buyer even in the C2C market (second-hand markets). According to Munaro and Tavares (2021) passports (in their research, material passports) are a mechanism to influence consumer behaviour concerning sustainable purchasing and responsible ownership by making sustainability aspects of a product life cycle. Providing information about a product’s sustainability, origin, and end-of-life options can help consumers reduce their environmental footprint and contribute to a more sustainable future. The development of tools like DPP is sustained by the digitalization process that society is also facing (Walden et al., 2021).

It is however important to notice, that the European Union designation for the DPP is not yet a universal one. According to van Capelleveen et al. (2023) other designations such as product passport, material passport, resource passport, recycling passport, and cradle-to-cradle passport, among others, are adding some noise and dispersion toward a more precise communication of research ideas, findings, and discussions about such passport development.

Being a kind of data storage, DPP will allow actors across the supply chain to insert and extract relevant product data and information (Jensen et al., 2023), contributing to a more sustainable economy (Berger et al., 2023; Plociennik et al., 2022). As defended by Reich et al., (2023), “a product passport should provide the necessary information to all stakeholders along the product’s value chain to act more circularly.”

Considering that the implementation of DPP in several activity sectors seems to become a mandatory practice for European companies soon, some are already working on that. However, if it is presented as a tool to promote or influence consumer behaviour as argued by Munaro and Tavares (2021), the question that arises is if consumers are aware of that. Companies will be obliged to implement it, but will consumers use it as expected? Under the first objective of this paper related to consumers’ knowledge about CE, we will also try to validate how known is this concept among European and non-European residents (within the sample used for the present research).

Summing up the concepts approached along the literature review, Table 1 presents the main variables and topics linked with some of the references found in the literature that even claiming (sometimes) in different directions reinforce their relevance when analysing the CE context:

Finally, it is important to note that in terms of regulations and guidelines, the European Union has been an active institution aiming at the promotion of CE as a part of its major goal which is the Green Deal. For that, several documents under different statuses, such as directives, recommendations, and communications, have been released targeting different sectors and stakeholders.

3 Methodology

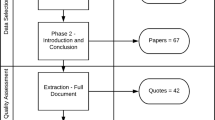

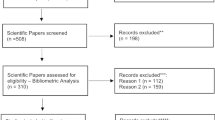

The purpose of this study was mainly to identify some behaviours and tendencies among consumers from three different countries towards to circular economy. It is a preliminary analysis that provides us with some insights about consumers behaviour. Those insights are expected to be used shortly to develop further research aiming to better understand the role of consumers in the circular economy and circular business models.

The current research was carried out using social media to spread the questionnaire. The objective was to reach individuals of different genders, ages, places of living and levels of education, to have a heterogeneous sample. During this period, a total of 495 answers were collected, (95 from Albania, 262 from Poland and 138 from Portugal). The choice of these countries was determined by the fact that Albania is a non-member state of the European Union, while Poland and Portugal represent the groups of the so-called New Union (accession of Poland to the EU in 2004) and the Older Union (accession of Portugal to the EU in 1986). Moreover, the economies of these countries show differences in terms of economic and social levels. This diversity may translate into different behaviours of consumers.

Taking into consideration some available information about CE, first it was realized that OECD performs from time to time a household survey (Environmental Policies and Individual Behaviour Change). The last survey was done in 2022 and published in 2023 (OECD, 2023), but none of the countries under survey in this article, were surveyed by the OECD. The lack of information about Albania, Poland and Portugal was one more reason for the development of the present research.

Currently, the data available about CE from the EU cover just two of the countries under research in this article, Poland and Portugal. Albania, not being an EU member (yet) do not have all the data to compare with EU members. However, as a cooperate country in what regards the green deal, some data is available, and it is interesting to notice that EU is working jointly with Albania to improve their CE.Footnote 2

From the Eurostat monitoring framework, it is possible to compare some data between Poland and Portugal (very few also with Albania through the European Environment Agency since Albania is considered a cooperating country) in relation to CE indicators related to consumption and consumers’ behaviour (Table 2).

According to the World Bank (2020) Albania has a low recycling rate of plastic waste at nearly 5% of the total amount of generated waste (166,000 kg in 2016), According to the same report, Albania needs to develop effective and efficient instruments in order to use less, reuse more, and recycle the rest. This can be addressed in many ways: through market-based measures for changing consumer and manufacturers behaviors and the materials they use, and for making recycling more economically attractive.

Albania is also an interesting case-study in terms of CE behaviours because “the 2020–2035 national strategy for integrated waste management aims to incorporate circular economy principles into the national waste management system. Still, about 30% of the population is not serviced by waste management infrastructure, encouraging waste disposal in landfills or old dumpsites. Waste is often dumped illegally in rivers or lakes—ultimately polluting Albania’s waterways and coast (World Bank, 2021).

Another comparative measure is the eco-innovation index among EU member states.Footnote 3 In 2022, among the 27 EU members, Portugal ranked the 15th position with an index of 106, while Poland ranked 26th with and index of 67. Poland’s poor ranking may be due to a number of factors, including financial barriers for entrepreneurs and consumers, a lack of awareness, and insufficient government spending on R&D activities. Even scoring better in this index, other studies (Colaço et al., 2022) place Portugal and Poland in the group of laggards when it comes to EU countries CE profiles. The other identified groups in the cited research were sustainable and optimizers. It means that there is still a way to walk (or run) in order to have all countries contributing to the Green Deal.

In regard to second-hand purchases, to our knowledge there is no valid statistical information on those countries. However, from the researcher’s knowledge about these countries, and some general readings, we can say that second-hand purchases are more frequent in Albania (mainly in rural areas) and Poland than in Portugal. Both in Albania and Poland flea markets and thrift stores are quite popular. In Portugal, second-hand purchases are more frequent trough online platforms. Those platforms are also getting popular in Poland.

The different contexts and the different indicators that we can find among these countries, combined with the different maturity levels in terms of EU membership, being Portugal a member from 1986, Poland since 2004, and Albania a candidate member led to the motivation to pursue the present research.

The behaviour and lifestyle of consumers play an important role in achieving sustainable development goals, including the CE goals. In order to minimize risks, education and actions to promote pro-environmental attitudes among consumers.

Assuming that CE is not a temporary change, but a long-term trend in support of sustainable development, it is necessary and urgent to take actions to raise awareness among market players (businesses and consumers). It is necessary to carry out research on consumer behaviour with regard to the propensity to choose green products and services. The consumer is particularly important in this regard, as he or she faces difficulties in determining demand, incorrect planning of purchases. There is a need for multi-sectoral research in value chains beyond waste management, the environment, as well as active education and increased consumer awareness for CE acceptance. This article aims to explore how familiar, concerned and committed are consumers towards to CE, and to look for different results according to the gender, generation, nationality, or education of consumers.

To realize the research, based on the stated objectives and on the literature review (summed up in Table 1), we can present a relation model that supported our research.

According to the model above the hypothesis to test are related to the impact that the first variables (age, gender, location and education) may have in the second group of variables (knowledge abit CE, second-hand purchases and knowledge and interest on the DPP tool). Along the research and according to the obtained results some other tests might be performed, in particular to try to identify different behaviours between EU and non-EU residents.

Regarding the age variable, the questionnaire was organized to identify the respondents’ generation where the following groups were distinguished:

-

Born from 1995 to 2012 (Generation Z)

-

Born from 1980 to 1994 (Millennials)

-

Born from 1965 to 1979 (Generation X)

-

Born before 1965 (Baby Boomers).

In terms of place of living the questionnaire asked to identify whether the respondent was living in a village, or the dimension of the city they were living in (from a small city, up to 20 thousand inhabitants, to a large one with more than 200 thousand inhabitants).

Considering education levels, the main options for respondents were primary, secondary, or different levels of higher education.

Aiming to identify differences regarding CE behaviours, and considering the type of data collected it was decided to support this research in a statistical technique used to examine the relationship between two categorical variables—he cross-tabulation analysis, that can be performed in the SPSS software (IBM® Software Statistics Version 28.0). It allows us to compare the distribution of one variable across the categories of another variable and determine if there is an association or dependency between them. By specifying the two variables of interest, it is possible to generate a cross-tabulation table that summarizes the counts, percentages, and other relevant statistics (Field, 2017; Pallant, 2020).

This is a frequent analysis in social sciences, market research, and other fields where categorical data analysis is important. It helps researchers understand the relationships and associations between variables, identify patterns, and test hypotheses about the interdependencies between categorical variables. To test the independence between variables while performing the crosstabs analysis, SPSS allows to request of a chi-square test. It is a statistical test to assess the association or independence between two categorical variables. It allows us to determine if the observed distribution of data in the contingency table significantly deviates from the expected distribution under the assumption of independence (Agresti, 2019). The hypotheses stated are the following:

H0

The Results of variable 1 do not depend on the results of variable 2 vs.

H1

The results of variable 1 depend on the results of variable 2.

To test the abovementioned hypotheses were used the Chi-square test, which allows us draw conclusions on the possible relationships between the variables under discussion. If the p-value is below the significance level (0.05 for a confidence level of 95%) it suggests evidence of a significant association between the variables. Conversely, if the p-value is not significant (> 0.05) it indicates that there is insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis of independence, implying that the variables are independent.

Strengthening the performed analysis, through the Chi-square test results that provide us with signals to independence rejection, another test, the Cramer’s V test offered by SPSS, assists us and it is requested in confirming this independence analysis. This test is a measure of association between two categorical variables. It provides information about the strength and direction of the relationship between the variables (Field, 2017; Sheskin, 2020). Cramer’s V test is a statistical measure that quantifies the strength of association between two categorical variables. It ranges from 0 to 1. A value close to 0 indicates a weak association, while a value close to 1 suggests a strong association. It is important to notice that this test is particularly useful when analysing larger contingency tables with variables having more than two categories. This information might be relevant because in this research several variables are composed of two categories. Even though it is a weakness, using this test will allow us to have a better understanding of the association levels identified in the research.

At this stage may also be relevant to mention the questionnaire used to collect data. The questionnaire included several questions as personal anonymized data, and different questions targeting the CE concepts and behaviours. The questions used to develop the present research are described in the next section. Along with the research question presented in the introduction, the support questions used are also listed. We consider that this approach will facilitate the interpretation and discussion of the results.

4 Results and discussion

As presented in the previous section the variables taken into consideration to search for causes for different behaviours towards circularity, were Location (Nationality and Domicile), Gender, Generation, and Education Level. Before starting with the results presentation let’s take a quick overview for these variables. Might be relevant to remind that in terms of literature review, these variables were already identified as relevant (with different results) in previous studies (see Table 1).

-

Nationality and Domicile: To analyse whether the country/place of residence may have an impact on circularity issues. This variable may also allow us to explore the possible differences between European Union/non-European countries).

-

Gender, Generation, and Education level: To analyse whether these variables may influence circularity knowledge and behaviours.

Considering the variables mentioned we started by testing their relationship with the precepted knowledge about the concept of CE. This might be presented as our first research question:

RQ1: Do the different variables under research influence the precepted knowledge about CE?

When asked to the respondents how familiar they were with this concept three options were given (1) I don’t know the concept; (2) I have an idea about it; (3) I know exactly what it is. Performing a crosstab analysis, the main results are summarized in Table 3.

The chi-square test (significance result = 0.001) allowed to confirm the independence rejection and identified the following tendency: In Albania were registered more answers than expected on the option “I don’t know the concept”, while in Poland and Portugal, the answers were lower than the statistically expected. Regarding the second option, “I have an idea” it registered the opposite results in all countries, Albania below the expected, while Poland and Portugal above. For the option “I know exactly what it is”, the counted answers were like the expected ones. However, it is important to notice that this variable association was not very strong. The Cramer’s V test presented a value of 0.136, which means a weak association. These results tendencies were also confirmed when testing EU versus non-EU countries. In this analysis, Cramer’s V test result was slightly higher (0.191) thus pointing to a weak association. Based on these results one can say that Polish and Portuguese respondents have a higher perception than Albanians, about the knowledge of CE meaning. These results may indicate that the efforts, through goals establishment and guidelines release, such as the European Green Deal, or the Circular Economy Action Plan, that have been established by the EU to promote a sustainable economy in the continent might be resulting.

By analysing the place of residence, in relation to the city dimension (urban, suburban, or rural areas), it was intended to explore whether the living place may affect the perceived knowledge of the respondents. However, the chi-square test indicated that the independence hypothesis should not be rejected (χ2 = 12.310, p-value = 0.138). This rejection was valid for the entire sample as well as for each country individually. This means that the country of residence may have an impact on the precepted knowledge about CE, but the living area (whether a village, a small or large city) does not influence the respondents’ knowledge, making us infer that CE policies might be designed at a national level.

Considering the perception of the respondents about their knowledge of the concept of CE, but searching for a gender tendency, the independence hypothesis was rejected. Once again, this rejection does not mean a strong association. From the Cramer’s V test, the association point out to a weak one (Cramer V test = 0.138). Anyway, considering that some association exists, in this case, it was identified that male hold a better self-perception of the meaning of the concept, than female. Currently, we cannot find a possible justification for these differences. The association is weak, but it might be interesting to check if the gender also presents different behaviours (to be tested ahead).

The hypothesis that follows considers the differences among generations, where the results point to not rejecting the independence hypothesis. So, we can say, that the CE concept perception is not much frequent in one or another generation.

To finalize the analysis, it was tested the presence of any relation or dependence between CE knowledge perception and education levels. In the first attempt, the results did not present statistical validity. However, neglecting the specific levels or categories of higher education (BSc, MSc and PhD) thus, considering all to a single category just as higher education, the dataset will be divided in 3 sections (Primary, Secondary and Higher Education). Considering this new scenario, it was possible to reject the independence hypothesis and verify that the level of education affects an understanding of the CE concept. The tendency is that the higher the level of education the better the perception of CE can be. Once again, according to Cramer’s V test, the identified association is weak (0.181).

As main conclusions from the first research question we can present:

-

In general, EU residents (in this case from Poland and Portugal) are more aware of the CE concept;

-

The patterns identification among countries was not observed when it comes to place of living;

-

Males had a better self-perception of CE knowledge compared to females.

-

Higher education levels were associated with a better understanding of the CE concept.

Not all the conclusions drawn allow a clear connection with previous studies, mostly because those previous studies point in different directions. Regarding location differences, we can say, that those differences might be related to institutional and cultural issues as identified by Grafström and Aasma (2021) and Hu et al. (2022). On gender issues, our research found that male have a better self-perception of the CE concept, and the result is aligned with (Edoria et al., 2023) research, that identified men as holding more environmental awareness than women, but the difference was not significant. (Mykkänen & Repo, 2021) also identified gender differences in regard to circular behaviours (in favour of male) but gender was identified as a weak predictor. A similar result, were gender had no moderate effect was also identified by (Kutaula et al., 2022). Gender does not seem to be a relevant variable on the CE knowledge, and from the literature review also on consumers’ behaviour.

After analysing the CE concept, the questionnaire tried to identify some behaviours towards CE and to verify whether the abovementioned variables might have any influence on such behaviours, by presenting the question as the following: “Have you ever bought or intended to buy second-hand products?”.

RQ2: Do the different variables under research influence second-hand purchases?

This information might be relevant for further research, namely, to explore new circular business models. Second-hand products might be part of the 10R framework of CE (Reike et al., 2018, 2022) in the second level of this framework—Consumption (includes activities/behaviours of Reuse, Repair, Refurbish, Remanufacture and Repurpose). Table 4 summarizes the relevant statistical results for the analysis.

Firstly, it is relevant to mention that 86% of respondents answered positively regarding the acquisition of second-hand products (these questions excluded high-value products such as cars or houses). Considering a country analysis, the positive answer to second-hand acquisition was 80% in Albania, 93.5% in Poland, and 73.1% in Portugal. These figures may not seem in accordance with some references found in the literature (D’Adamo et al., 2022; Wilts et al., 2021) who claim low market shares for these transitions. However, it is important to notice, that the question was not about the percentage of purchases, but just if the respondents were buying second-hand products. The figures just allow us to conclude, that second-hand shops are known and used by the respondents, but we can’t infer about the level of purchases done in comparison to new products.

Testing the tendency or intention to buy second-hand products and linking it with nationality, the independence hypothesis was rejected. The association identified here, even low, is a bit higher than in the previous analysis (Cramer V test = 0.231). With the association information, we could explore a bit further the results and confirm statistically that in Albania and Portugal, people are buying fewer second-hand products than in Poland. Going a bit further it was realized that the most frequent answers (reasons to buy second hand products) from Polish respondents were lower price and ecological reasons. This result suggests both an economic but also environmental concerns from Polish respondents. It also suggests that we cannot talk about the existence of a difference between EU and non-EU countries. In this analysis, the independence hypothesis was not rejected to the same confidence level. Proceeding with a similar test, but now considering the domicile, it was possible to reject the independence hypothesis, but the results are not clear. Just in smaller cities (up to 20.000 inhabitants) people are buying fewer second-hand products than expected. Performing the same test for each country individually, the independence hypothesis is rejected just for Portugal. There the tendency is the same: only in smaller cities people are not so committed to buying second-hand products. We might say, that even with a low level of association in the Portuguese sample (Cramer’s V = 0.280), the Portuguese sample may be influencing the general results.

Regarding gender and generation, the independence hypothesis was also rejected. The tendencies identified were that female are buying more second-hand products than male. This behaviour either is not aligned with the results from RQ1, where male presented a higher self-perception of the CE concepts, or second-hand purchases are not related to circular behaviours. Like men, baby boomers, generation X and Millennials are not as enthusiastic about second-hand products as generation Z. This might mean that the new generation of consumers is more open-minded in what comes to not buying new products. With this behaviour, this generation might be contributing to a less linear economy providing for the products’ life extension. Regarding the levels of association tested by Cramer’s V, the low level of association is kept for both variables. Generation presents a better (even low) association result (Cramer’s V = 0.227). It might be interesting to remind here, that V Cramer’s is used just to give us an idea about the association level, but this test is more useful when the variables have more than 2 categories. In some cases, as generation, one of the variables has just 2 categories. In gender, both variables have 2 categories. So, up to now, and for the following tests, it is important to notice, that the focus is most on the chi-square test, rather than in the Cramer’s V.

Considering education, it was not possible to reject the independence hypothesis. Summing up, one can say, that Polish people are the ones that are most committed to second-hand purchases both for economic and environmental reasons. However, the economic motivation took the first place to justify second hand purchases.

In terms of places of residence, the results indicate that smaller cities in Portugal are influencing the results since people living there are not so committed to second-hand purchases. The justification might be the social element, since, in smaller communities people know each other and the social element of using or buying something discarded from someone in the community might be seen as a poverty signal, and not as a circular behaviour. Later, the analysis was focused on the CE self-perception in Portugal, where it was found, that just in small cities the count results for those that claim to know the concept of CE, were lower than the expected ones. So, even lacking further confirmation, it is possible to reinforce one conclusion from several authors (Bigliardi et al., 2022; Maťová et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020) among others already mentioned in this paper: knowledge or lack of it (about CE) influences people’s behaviour regarding circular or linear practices. Thus, Portuguese residents in smaller cities, may not be committed to second-hand purchases, because they are less aware of circular practices. Anyway, it should be reminded, that the test to find differences among the places of residence both at the entire sample as well as by country was not explored since the independence hypothesis was not rejected.

From this research question the main conclusions can be summarised as follows:

-

Albania (non-EU member) had fewer positive responses to second-hand purchases than Poland and Portugal;

-

The city dimension did not significantly influence second-hand purchases, however, there are some insights pointing to more active market in rural areas;

-

Females and generation Z are more inclined towards second-hand purchases;

-

On the opposite to the knowledge results, no significant impact from education was identified on second-hand purchases.

After analysing consumers’ behaviour towards second-hand products, another question about purchasing new products was raised. Through such analysis we tried to identify whether price was an influencing factor on the linear or CE behaviour, asking the respondents under different price scenarios if they used to buy impulsively a new product or to avoid such a purchase. This takes us to the next research question.

RQ3: Does nationality influence linear or circular buying under different price levels?

The price levels were defined as follows: (1) Product up to 25€; (2) Products with a cost between 25€ and 100€; (3) Product above 100€. The descriptive results are presented in the Table 5.

Interesting to notice, that only in Portugal the avoid buying tendency is increasing as the product price increases. In Albania, people, tend to buy new products no matter the price. A possible explanation for this result might come from the high degree of informal economy on new products. At the same time, younger consumers, looking to follow the latest market trends, are looking for new products in a formal or informal economy, as they have the financial support of their families. In Poland, it was found that people avoid buying new products when they are cheaper or more expensive. Middle-range price products are in general bought new by Polish respondents. Considering that the Polish results are based in a significative number of answers from a younger population, and once again, this segment tries to follow the market (and marketing) trends, the justification may arise from a social perspective: choosing mid-range price products to buy new is a compromise between quality and price. Cheaper products are not so trendy, and more expensive products present the price constraint. The results found, are an interesting issue to explore in future research.

Performing the chi-square test it was verified that the independence hypothesis between nationality and buying decision can be rejected for all price categories as can be seen in Table 6.

The results can be summed up as follows:

-

Price influenced buying decisions differently across nationalities;

-

Portuguese respondents tended to avoid impulsive purchases in all price ranges;

-

Polish respondents tended to avoid a linear approach for middle-range products, being more circular for higher-priced items but also for low-price items;

-

Albanians displayed a linear approach across all price ranges;

-

EU countries present a more circular approach.

Even lacking further research this linear behaviour might be due to the fact that Albania is yet a non-EU country, where such approaches towards CE are only part of separate individual behaviour and not as a national policy. Bearing in mind lack of CE knowledge and perception previously identified, together with the existence of an informal economy we can say that the lack of information and policies aiming CE, might be two potential justifications for the Albanian linear consumption approach. An important input for future research is related with categories of products. In the literature it was possible to find oriented research for items such textile, or electronic devices. A moderator question checking if the items categories influence the new or second-hand purchase must be considered in future research.

Having these results in mind, we proceeded to the next analysis, which is related to the reasons that make people buy second-hand products. This question allowed the respondent to choose different options such as price, quality, brand, design, features, others’ opinions and ethical or environmental reasons. For each of these possible answers the respondents could choose the following options: “Definitively”, “Probably yes”, “Rather no”, “No”, or “I have no opinion”.

RQ4: What are the main reasons to buy second-hand products?

Considering the type of data that was collected the results were analysed in an aggregated percentual basis, rather than with crosstabs analysis. To simplify this analysis just the most relevant answer (Definitively) was considered. The results are presented in Table 7.

Price was one of the main reasons to buy second-hand products, but in the first place as a decision motivator, we got “Quality” with 63.6% of answers (multiple choices were allowed for line and column options). Ethical and environmental issues scored more answers in the “Probably Yes” (35.6%) option, along with Brand (38%), Design (38.8%) and Features (39%). Interesting to notice that the score of ethical and environmental issues was the lowest among the options presented as reasons to buy second-hand products (Table 8).

Comparing the results on EU and non-EU countries, it is interesting to notice that the most frequent answer (in the Definitively option) in EU countries was “Price” followed by “Quality”. In Albania (non-EU) the most frequent answers were “Quality” with 67.2% and “Features”. The “Price” option scored 45,3% in fourth place, after the “Brand”. Regarding “ethical and environmental issues” in both regions the highest score was obtained in the “Probably yes” option. In EU countries the score was 33.5% while in Albania was 44.2%. Combining the results from the options “Definitively” and “Probably yes” the non-EU region takes the lead with a sum of 68.4% against 59.8% in the EU countries under analysis.

Even with a clear answer to this question, putting quality and price as the most significative motives makes it difficult to reach a conclusion. In the same questionnaire, there was another question asking to identify the most relevant factors to decide on a second-hand purchase. Not surprisingly, “Lower Price” was the most frequent answer (41.8%), but in second place we got “Ecological and Sustainable Attitude” with a score of 37.4%. This time, “Quality” scored in 4th place with just 6.5% after “Increased Availability” with 8.1%. Analysing EU and non-EU countries the results are, let’s say, curious. For EU countries “lower price” scored 50.2% followed by “ecological reasons” with 46.3%. In non-EU countries, the best score was for “increased availability” (35.8%) followed by “quality” (31.6%). After these options the best score was for the option “no opinion” and only after this one we got “lower price” with 6.3%. The option “ecological and sustainable attitude” didn’t get any votes.

This might mean that price is a real concern, mostly in EU countries since the answer is in line with the previous one, but circularity issues only are appointed as relevant when directly asked. Considering the results comparing EU and non-EU countries, it was interesting to notice a completely different behaviour. While EU respondents are mainly worried about price and ecological reasons, the non-EU residents seem not to be worried about any of those issues. These results may also lead us to conclude that in a direct question the most socially valid response comes from EU residents while in a not-so-direct question, like the previous analysis, this concern does not appear as a main reason for second-hand purchases.

In the literature review, some studies pointed to different results in terms of motivation for a circular approach (Bigliardi et al., 2022; Cano et al., 2023). These results show that even in the same questionnaire, people are giving different answers to similar questions. It also might suggest that even those that present a more circular approach, still do not do it for sustainability motives. Even seeming to be a “dark side” of consumption these results are still interesting. They may open clues to producers and sellers in terms of marketing strategies. Even advertising for circular products, other features like quality or price, are still very relevant issues for consumers.

Another issue that might be important to define a circular business model and to think about selling strategies is related to the marketplace.

RQ5: Where are customers acquiring second-hand products?

In a descriptive analysis, it was possible to find that most second-hand purchases are done through the web (websites or apps) 46%. Then the most frequent answer was second-hand shops with 28%, and the option other was the third most chosen with 20%. Interesting to notice that nobody chose the options “open markets” and “regular shops with second-hand offers” since those two were also options available in the questionnaire. Performing a chi-square independence test between nationality and purchase place, it was possible to reject the independence hypothesis. From the results, it was also possible to identify a tendency to buy online in Poland and Portugal while in Albania, respondents tended to answer the “other” option. This option was the most frequent one among Albanian respondents. The "other" result can be explained by the fact that in Albania the most popular online shopping apps and websites are national such as aladin or buzi store, and not the international ones listed in the questionnaire. In terms of international platforms, the most frequent in Albania is eBay, that was not included in the questionnaire option list. The Cramer’s V test points to an association level of 0.4, which corroborates the differences registered among countries. As expected, the same results were also confirmed in the comparison of EU versus non-EU countries. Doing the independence test considering domicile, we got independence rejection. However, even noticing that smaller cities and villages prefer to buy from the web, in the largest cities the tendency was to buy in “Other” places. Exploring a bit further, it was possible to validate that most of the respondents who live in a large city (over 200 thousand) are Albanian. So, this domicile tendency is affected by nationality. This immediately points to the need to develop further research regarding the domicile impact on circularity.

Considering the purchase place in relation to other variables, the independence hypothesis was rejected for the gender variable. Men are more oriented to buy from the web, while women prefer to acquire those products from second-hand shops. The Cramer’s V presented a low level of association (0.210) but once again we are analysing a variable (gender) with just two categories. This low association are also aligned with the literature that mostly associates gender as a weak moderator in terms of CE.

Regarding generation once again was possible to identify some tendencies validated by the independence rejection through the chi-square test. Cramer’s V points to a low association level (0.203). Baby Boomers are not comfortable using the web to buy second-hand products, and surprisingly generation Z seem to be the generation that prefers to buy from second-hand shops. Even with a significant percentage of generation Z individuals buying through the web (45.7%) there are still 35.5% of these individuals that prefer second-hand shops. This clarification is important to keep in mind that even with the identified tendency that generation Z is the one that prefers second-hand shops, in fact, is true when comparing it with other generations. However, most of these individuals are still buying through the web, not with an overwhelming result as could be expected, but still, they are connected through the web.

Regarding education, independence was also rejected, but the results did not allow the identification of a clear tendency. People with primary school are choosing more frequently to buy from second-hand shops, while others with secondary school and university levels prefer to buy through the web. However, it was also noticed that people holding at least a bachelor’s level also tend to choose the option “other”. Considering that no more information was gathered, it is difficult to identify what this “other” option means.

From the marketplaces more frequent to second-hand purchases we can conclude that:

-

Web platforms or mobile applications were the most common source (46%)—The digitalization in favour of CE (Charnley et al., 2022; Yeap et al., 2022).

-

Second-hand shops scored 28%;

-

National differences were observed, with Poland and Portugal favouring online purchases;

-

Males prefer to buy from the web, while females favour second-hand shops.

To finalize the respondents were also questioned about the DPP. To the question “Would you like to have access to a QR-code associated with products? (with information about materials used, recycling options, maintenance suggestions, repair shops, and end-of-life procedures)” the answer was clear, 62% of the respondents would like to get this feature associated to products. It is important to mention that this question was referring to products in general and not to second-hand products.

RQ6: Do the different variables under research influence DPP options and knowledge?

The independence tests allowed us to conclude that Polish respondents are the ones who show less interest in a digital label containing the mentioned information. There are several possible reasons why Polish consumers may not show much interest in the digital product passport. (1) Low awareness: This may be due to a lack of awareness among Polish consumers about the existence of a digital product passport. If they do not have access to information about it or have not been properly informed, then they may simply not know that such an option exists. In fact, the European Commission is not actively promoting it, but this is a concept introduced with the new Circular Economy Action Plan. (2) No access: Some consumers may not have access to the appropriate technologies or tools to check the digital passport of a product. This may include the lack of smartphones or mobile apps that allow access to this information. This may lead to refusing a tool like DPP. (3) No need: If consumers feel that a DPP does not add value to their shopping experience or influence their purchasing decisions, they may not feel the need to use this option. (4) Distrust of technology: Some consumers may be wary of technology and fear that DPP may violate their privacy or be vulnerable to hacking. Lack of trust in modern technological solutions can stop people from using them. (5) Lack of standards and regulations: The lack of clear standards and regulations for digital product passports can leave consumers unaware of what to expect or unsure if this information is reliable. Currently, standards and regulations about DPP are not available. (6) Traditional methods of product checking: Polish consumers may be accustomed to traditional methods of checking products, such as reading labels on the packaging or using reviews of other consumers. They may consider these methods sufficient and see no need for digital product passports. It is worth emphasizing that gradually growing awareness, consumer education and developing technologies can change this situation.

Getting back to the general results, in terms of domicile, gender, and education it was not possible to take any conclusion, because the results from the crosstabs analysis did not meet the statistical requirements. For the variables over 20% of the cells presented a value below 5. When this happens the validity of the chi-square test may be compromised (Agresti, 2019).

Generation independence was rejected by the chi-square test, but again with a low value from the Cramer’s V test (0.172). Generation X and Millennials were the generations that showed more interest in this label. According to the literature having the Millennials as a generation with an interest in digital tools was expected, however, it was expected that generation Z (younger) would show more interest than generation X.

To the question are you familiar with the DPP only 32.5% assumed to know the concept. Concerning the knowledge of DPP versus nationality, independence was not rejected. However, it could be rejected for the comparison between EU and non-EU countries, and in this case, it was interesting to notice that Albanian citizens seem to be more familiar with this concept than EU citizens (Polish and Portuguese). However, in a two-by-two categories analysis, Cramer’s V test presented a score of 0.128. Regarding the positive results on the Albanian side, this was a surprising result. In Albania, the DPP concept is not spread, and we believe that a few people know the real meaning of it. Considering the results obtained, and bearing in mind that the questionnaire did not explain the DPP concept, since the questionnaire only had one question to check whether respondents were familiar with the DPP concept, we fear that the question or the concept of DPP may have been misinterpreted. Perhaps the concept was associated with the coding label of the product, not with the tracking information and origin of the products used in the CE economy. Unfortunately, the questionnaire does not provide us with more detailed information, but it opens another research possibility which is the exploration of DPP reception from the consumer side.

In terms of domicile, gender, and generation independence was not rejected. Regarding education, the independence hypothesis was rejected. Even with a low result for Cramer’s V test (0.161), respondents with a higher education degree are more familiar with the DPP concept.

Summing up the results related to DPP we can list as more relevant the following:

-

Only 32.5% claimed to be familiar with the DPP concept

-

Polish respondents showed less interest in DPP;

-

Generation X and Millennials presented more interest in the tool;

-

Surprisingly, Albanians seemed more familiar with DPP compared to EU respondents.

As a general conclusion from the results, and presenting it as a bridge to the next section we can highlight the following:

-

Nationality played a significant role in perceived CE knowledge, second-hand purchases, and attitudes towards DPP;

-

Gender and generation differences were observed in second-hand purchases

-

Education impacted perceived CE knowledge but not second-hand purchases;

-

Price influenced buying decisions differently across nationalities.

5 Conclusion

The present section aims to summarize the main conclusions from the research developed in Albania, Poland and Portugal, aiming at identifying consumers’ knowledge and behaviours towards CE. The most relevant ones were highlighted in the previous section, so we intend to enrich this section by identifying some study limitations and future research.

From the literature review it was possible to identify different research focusing on single fields of industry or individual consumer products, such as textiles, smartphones, however, we consider that further knowledge is necessary when it comes to basic consumer perspectives that affect the CE as a whole. For that reason, this study was developed, however, it is important to note that this research is a preliminary step to better understand consumers’ perspectives on CE. This will also lead to a questionnaire refinement in order to get a deeper perspective on some topics. Immediately, we can point out that further research will be necessary to deepen both the approached topics as well as the number of answers obtained.

The results obtained from 495 valid questionnaires allow us to draw some conclusions and identify some topics that require further research. The analysis of the variables nationality, gender, generation, education level, and domicile provided valuable insights into the perception and behaviours related to circularity. Before summing it up, it is important to notice that some associations were identified, but in general, the association level was not very strong. This weak association might be pointed as a limitation but opened future research possibilities. Even with a weak association some differences and trends could be identified. In general, we can say that nationality, gender, generation and education may impact different ways on consumers’ circular behaviour.