Abstract

The interest in greenwashing has grown in recent decades. However, comprehensive, and systematic research concentrating on the evolution of this phenomenon, specifically regarding its impacts on stakeholders, is still needed. The main purpose of this study is to provide an overview and synthesis of the existing body of knowledge on greenwashing, through a bibliometric study of articles published up to 2021, identifying the most relevant research in this field. Special attention is given to the latest articles that link greenwashing to stakeholders, identifying gaps and future research opportunities. A bibliometric analysis and literature review was performed on 310 documents obtained from the Web of Science database, using the VOSviewer software program. This article identifies the most influential aspects of greenwashing literature (authors, articles, journals, institutions, and keyword networks). The most recent articles on the effect of greenwashing on stakeholders were also analyzed, which made it possible to identify trends, gaps, and opportunities for future research. These topics include greenwashing impacts on branding, consumer attitudes and intentions, mainly on purchase behavior, B2B relationships and the definition of taxonomy for greenwashing, considering the different practices. This study offers a thorough analysis on the state-of-the-art, as well as a closer look at the impacts of greenwashing on various stakeholders, providing a list of suggestions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Society is growing more sensitive and concerned about the environmental practices adopted by firms (Musgrove et al., 2018). As environmental practices are appreciated by society (Torelli et al. 2020), firms face significant pressure to conform to stakeholder demands (Kim et al. 2017). So, as firms realize that their image, legitimacy and reputation are at stake, they may be tempted to exaggerate, mislead or embellish their external communications regarding their environmental actions (Kim et al. 2017) in order to create a favorable image (Chen et al. 2014). In this way, firms exhibit positive green communication or pretend to be environmentally friendly (De Jong et al. 2018; Delmas and Burbano 2011; Nguyen et al. 2019), but what the firm communicates may be different from its actual behavior (Gatti et al. 2021). Hence, when firms mislead or deceive society regarding their environmental practices or the environmental benefits of their product or service (Delmas and Burbano 2011), they engage in greenwashing. At the same time, consumers are increasingly aware and, consequently, more skeptical about the authenticity of corporate environmental claims (Lyon and Montgomery 2015).

The term “greenwash” has been the subject of interest among academics, mostly in the marketing field (Lee et al. 2018), with a focus on consumers or decision-making by the general public (Contreras-Pacheco et al. 2019; Nyilasy et al. 2014; Szabo and Webster 2021). Additionally, greenwashing literature studies have recognized the negative consequences of these practices, mostly on consumers (Chen and Chang 2013; Nyilasy et al. 2014). Thus, greenwashing has become a hot topic in the literature with an impressive growth in the last two decades, due to public interest regarding greenwashing activities (Gatti et al. 2021).

Recently, scholars have begun to summarize the research on greenwashing (de Freitas Netto et al., 2020; Gatti et al., 2019; Montero-Navarro et al., 2021; Saleem et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2020). These studies have focused on mapping and analyzing the academic production regarding greenwashing phenomenon (Andreoli et al. 2017), providing an evaluation and progress of the field’s trends, and synthesis of the results provided by previous studies (Gatti et al. 2019). Some authors even focus on articles directly associated with agriculture, food industry and food retail (Montero-Navarro et al. 2021). Others, investigate greenwashing main concepts and typologies (de Freitas Netto et al., 2020), while others focus on its causes, taxonomy and consequences (Yang et al. 2020). Despite presenting valuable insights on this topic, a thorough examination involving its effects on the stakeholders is still lacking (Gatti et al. 2021; Pizzetti et al. 2021). This research therefore attempts to provide a comprehensive overview of trends and the current position of the academic studies on greenwashing, focusing on its effects on stakeholders. To that purpose we consider stakeholders, shareholders, investors, consumers, customers, clients, employees, workers, partners, suppliers and competitors as the focus of the investigation, and how they might be affected by greenwashing actions, identifying research gaps and providing potential future research directions. For this purpose, the authors carried out a bibliometric analysis supported by VOSviewer, followed by a literature review of the articles obtained from Web of Science (WoS).

The results of this investigation are especially relevant considering the importance of greenwashing. This article is structured as follows: it describes the adopted methodology, followed by Sects. 3 and 4, where the results of the bibliometric analysis and literature review are presented. Section 5 exhibit identified gaps and provides future research directions. The last section offers the final considerations.

2 Methodology

2.1 Research methodology

To pursue an in-depth understanding of the state of the art of greenwashing literature, focusing on its effects on stakeholders, this study used a two-step methodology: first, the authors conducted a bibliometric analysis, which indicates the evolution of the research in the greenwashing field. Bibliometric analyses are quite useful for decoding or interpreting a wide set of data in a precise way, which allows making advances in a certain field in several ways (Donthu et al. 2021). Additionally, bibliometric mapping makes it possible to conduct a statistical evaluation of several connections across publications, providing a clear insight on the topic by visualization of the maps (van Eck and Waltman 2010). The second step consists of an overview of the current state of literature, by means of a literature review.

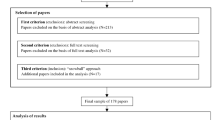

A systematic literature review is defined as the “means of identifying, evaluating and interpreting all the available research relevant to a particular research question, topic area, or phenomenon of interest” (Grant and Booth 2009). This type of approach allows a transparent and reproducible process of selection, analysis and reporting of previous research on a specific topic (Denyer and Tranfield 2009). The authors adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) approach. PRISMA is used to help authors improve their systematic reviews reporting (Page et al. 2021). PRISMA incorporates four sequential steps: identification, screening, eligibility, and study inclusion. This framework assures transparency in the selection and analysis of included studies and allows for other investigators to replicate this process (Booth et al. 2020).

2.2 Method

From the several databases available for query, the authors used WoS, because it is considered the most reliable, powerful and most trusted database in the world (Saleem et al. 2021), frequently used for bibliometric studies in management and organization fields. Nevertheless, the authors acknowledge that other studies might be indexed in other databases, and it is possible that some might have been left out of this analysis. The records, which were later used in the review, were identified on December 28, 2021, in WoS core collection, with a time frame including all years to date, with no limitations on document type, language, or citations databases.

Similar to other authors’ approaches (de Freitas Netto et al., 2020; Gatti et al., 2019), and in order to assess the true dimension of literature citing the term greenwashing, we used the term “greenwash*” in a Topic search, returning 508 articles. In other words, we used Boolean Proximity search, to help us find specific words that are near greenwashing (i.e., greenwashing, greenwash, greenwashed, greenwashes). As the asterisk represents any number of characters, the search will encompass all these words. To narrow our research and focus on our objectives, we subsequently limited the number of documents based on the selection of document type, citation databases, data rage, language, and categories. Exclusion criteria and selection process are described in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (see Fig. 1). We excluded 198 documents during the screening process, leaving 310 articles to track trends in the usage of greenwashing in the academic literature.

The authors used information obtained from WoS to deliver productivity measures about the research field, considering the historical evolution of the publications, the most influential articles, the main journals where they were published and the most prolific authors. This investigation also includes a bibliometric mapping approach using the VOSviewer software to analyze what the patterns and hot topics are in the field of greenwashing. VOSviewer makes it possible to create and visualize maps, taking into account the co-citations of author or journal; bibliometric networks based on citation, co-citation, co-authorship, bibliographic coupling, amongst others (Moya-Clemente et al. 2021). It is quite useful for displaying large bibliometric maps in an easy-to-interpret way (van Eck and Waltman 2010).

To establish a connection between greenwashing and its impact on different stakeholders, and to maintain the accuracy of our study, we executed supplementary filtering processes (Dangelico and Vocalelli 2017; Pizzi et al. 2020). Initially, we utilized keyword combinations to exclude articles that might address topics unrelated to the effects of greenwashing on stakeholders (Drejerska et al. 2023). We only considered articles that contained the combination of both the term “greenwash*” and stakeholder, shareholder, investor, consumer, customer, client, employee, worker, partner, supplier or competitor. In this process we excluded 112 documents. Second, although the selected terms (e.g., greenwash* and stakeholder*) were mentioned in the title and/or keyword, and/or abstract of the article, there is always the risk that this is not the central focus of the paper. Thus, using a double-check process, we manually reviewed all keywords, titles, and abstracts of the articles, and, when needed, the entire content of each paper included in the data base, excluding 159 documents that were not relevant to our subject of investigation. 39 articles fully met the review protocol, as presented in Fig. 1, and were used in the literature review.

To gain insight into potential avenues for future research, it is imperative to understand the latest research trends Thus, we employed a methodology recommended by Oliveira et al. (2019) to analyze recent articles and papers published by the most cited authors. This involved scrutinizing the most recurring topics and determining the frequency with which they were directly or indirectly addressed in the literature. By conducting such an analysis, we can reveal gaps and trends that have yet to be explored (de Oliveira et al. 2019; Tallon et al. 2019).

To investigate these trends and gaps, we adopted a similar approach to Juliani and Oliveira (2016) who utilized literature from the previous three years. Accordingly, we limited our analysis to the most recent publications (i.e., the period from 2019 to 2021) to uncover research gaps and potential avenues for further investigation (Kraus et al. 2020). This examination of highly cited and recent literature will provide robust insights into fruitful directions for future research. The number of citations was also considered, as only the ones that were cited at least one time were included. Therefore, limiting our analysis of referenced documents to the most prominent articles (Frerichs and Teichert 2023). This final step resulted in 24 articles.

In summary, the first and most extensive dataset consisted of 310 articles, and it underwent bibliometric analysis to identify the most relevant research in the field of greenwashing. The second dataset, comprising 39 articles, was utilized in the literature review to explore the influence of greenwashing on stakeholders, as per the objectives of this investigation. Finally, the third dataset, encompassing 24 articles, was used to identify research gaps and future investigation opportunities. The outcomes obtained during each stage of the systematic review process are illustrated in Fig. 1.

* The research began with the usage of the term “greenwash*” (i.e., greenwashing, greenwash, greenwashed, greenwashes) in a Topic (title, abstract, author keywords, and Keywords Plus) search.

** Exclusion based on the selection of document type, citation databases, data rage, language, and categories:

-

Document type: Article.

-

Citation databases: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, ESCI.

-

Data range: all years to 2021.

-

Language: English.

-

Categories: (count > 10): Business (101), Environmental Studies (98), Management (68), Environmental Sciences (65), Green Sustainable Science Technology (60), Ethics (26), Communication (25), Economics (25), Business Finance (23) Engineering Environmental (22), Hospitality Leisure Sport Tourism (18) and Political Science (11).

*** Exclusion based on:

Reason 1 – Additional filtering keywords: Articles that did not included both keywords: Greenwashing and several stakeholders: TS=(greenwash*) AND (((((((((((TS=(stakeholder*)) OR TS=(shareholder*)) OR TS=(investor*))) OR TS=(consumer*)) OR TS=(customer*)) OR TS=(client*)) OR TS=(employee*)) OR TS=(worker*)) OR TS=(partner*)) OR TS=(supplier*)) OR TS=(competitor*)

Reason 2 – Relevance to the study based on the reading of keywords, titles, abstracts, and entire document, if necessary.

**** Exclusion based on:

Reason 3 – Features less than 1 (one) citation.

Reason 4 – Exclusion based on year of publication (before 2019).

Adapted from: Page et al. (2020)

3 Results and discussion

The following analysis comprises the 310 articles related to greenwashing that were published up to 2021. These records can be found in 171 different journals, written by 739 different authors, affiliated with 442 institutions, based in 56 different countries and the articles had 8,308 citations (7,332 without self-citation).

3.1 Analysis of the overall growth trend

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of greenwashing publications and annual citations. The first article was reported in 2000, in Environmental & Resource Economics Journal, with the title “Green business and blue angels – A model of voluntary overcompliance with asymmetric information”, written by Kirchhoff (2000). The number of studies was limited, however, since 2011 and largely since 2017, there is a significant increase in studies. It is possible to identify three stages in greenwashing literature (2000–2010; 2011–2016 and 2017–2021). In fact, 69% of the total publications occurred in the last 5 years (i.e., 2017–2021), which reflects the increasing interest in greenwashing studies. This interest may be related to the growing awareness of environmental issues and social practices embraced by corporations (Musgrove et al., 2018).

3.2 Publications by country

Among the top 10 countries, the USA is clearly the most productive country, with 87 articles and 3870 citations. England and the People’s Rep. of China follow with 37 and 28 articles, respectively. Most of the studies are conducted in developed economies, with the exception of the People’s Rep. China (see Table 1). Thus, it seems that investigations in developing countries are scarce (Jog and Singhal 2020).

Some of the documents were published in co-authorship with other countries. The clusters of these co-authorship can be seen in Fig. 3.

In Fig. 3, the higher the circle is, the greater the number of articles published in that country. The node representing USA has a significant position in the network, corroborating the fact that it is the most productive country. Additionally, the collaborations between scholars in two countries are measured by the distance between circles. Thus, there are 5 main clusters of co-authorship between countries. The first cluster (red) includes Denmark, France, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland. The second (Green) Brazil, Canada, England, New Zealand, and Poland; the third (Blue) – Belgium, Italy Netherlands, and Spain; the fourth (yellow) – Australia, the People’s Republic of China and USA, and the fifth (purple) – Austria, Germany and Turkey.

3.3 Publications by institutions

As depicted in Table 2, University of Michigan and St. Anna School of Advanced Studies are the most productive organizations, with 6 and 5 publications, respectively.

3.4 Publications by author

Out of the 739 authors, 48 of them were cited more than 100 times and 17 authors had been cited more than 200 times. The most prolific authors in greenwashing literature are highlighted in Table 3, which considers the contribution as an author or co-author. Thomas P. Lyon achieved 854 citations with 5 published articles, while Xavier Font, with the same number of published articles, achieved 360. It is important to note that WS Laufer, with only one article, regarding Greenwashing, received a total of 503 citations.

3.5 Publications by journal

Out of the 171 sources, 33 journals had more than 50 citations and only 16 journals had more than 100 citations. The top ten, with more articles in the greenwashing literature, are highlighted in Table 4.

While the 310 articles were published in over 171 sources, most appear in a few key journals. 34% of all identified articles were published in the top 10 journals. About 77% of these cited articles were published in the top 4 journals. Therefore, they are of special importance in greenwashing research.

Sustainability is the most influential research journal, with 25 publications on Greenwashing. However, Journal of Business Ethics, with only 22 publications, received a total of 2104 citations. It is interesting to note that Organizations & Environment, with four articles, achieved 222 citations.

3.6 Mostcited articles

A view of the 10 mostoften referenced publications provides a first glimpse of important topics in greenwashing research. Table 5 summarizes the scientific publications cited most often.

These articles include overviews on reporting (Font et al. 2012; Hahn and Lülfs 2014; Laufer 2003; Mahoney et al. 2013), financial performance (Wu and Shen 2013), audit (Lyon and Maxwell 2011), Corporate Social Responsibility in the banking industry: Motives and financial performance, and on communication (Lyon and Montgomery 2015; Parguel et al. 2011). Other articles focus on greenwashing drivers (Delmas and Burbano 2011) and greenwashing effects on customers.

3.7 Keywords analysis

Our research indicates that of the 1670 different keywords, 99 had a minimum number of 5 occurrences. Considering that some authors use different words to express an analogous concept, we screened all keywords that identify similarities and replace them with a single keyword (Dabić et al. 2020).

The analysis of keywords exposes hotspots and trends in the research topics that are crucial for understanding advances in the field. The aim of this analysis is to recognize the most popular research topics and find what the trends are in keywords over time through the overlay visualization provided by VOSviewer. The authors used the “full counting” method, keeping only the keywords that appeared, at least, ten times (40 keywords). The 3 most relevant terms were found: greenwashing, corporate social responsibility, and management, resulting in the same number of clusters. Based on these three categories, the connection between the keywords can be examined.

Figure 4 displays 3 clusters, whose definition is based on the items that complement them, as shown in Table 6 .

Cluster 1 (red) is related to greenwashing outcomes. It includes terms like sustainability, impact, perception, attitudes, consumer, consumption, purchase intention, trust, and word of mouth. The relevance of stakeholder perceptions, and consequent attitudes towards corporate greenwashing practices, may have been one of the main concerns that led scholars to focus on this topic. The second cluster (green) encompasses the firms’ progress and success by adopting Corporate Socially Responsible practices. This cluster is composed of keywords related to performance, legitimacy, disclosure, and sustainable development. The existence of this cluster reflects the possibility that true, ethic and real socially responsible corporate behaviors can improve firms’ performance and development. The third cluster (blue) is related to pervasions in the firms. It comprises terms such as management, governance, risk, climate change and pollution.

Below, the overlay visualization (Fig. 5) demonstrates the trends in keyword changes over time. In Fig. 5, the blue part corresponds to older investigations while the yellow part corresponds to more recent investigations. The figure uncovers some hotspots that were created in the field recently, including “perception” (18 times in 2019), purchase intention (11 times in 2020), skepticism (12 times in 2019), word-of-mouth (13 times in 2020), antecedents (11 times in 2020) and trust (27 times in 2019) in the red cluster, and governance (19 times in 2019) in the blue one. Therefore, it appears that there is a transition from studies related to the firms’ legitimacy, innovation, and development, to the effects of corporate greenwashing, namely in the perceptions of this practice, skepticism, purchase intention, trust, and word of mouth.

4 Greenwashing and its effects on stakeholders

A detailed examination involving greenwashing and its effects on stakeholders is needed (Gatti et al. 2021; Pizzetti et al. 2021). Therefore, the authors considered 39 articles that related both terms and performed a literature review.

Greenwashing is multifaceted in nature (de Freitas Netto et al., 2020), as it can occur at the corporate level (i.e., be misleading or deceptive in regard to the environmental practices of an organization) or at the product/service level (i.e., be misleading or deceptive in regard to the environmental benefits of a product or service) (Delmas and Burbano 2011). These practices can be categorized as claim greenwashing and executional greenwashing (de Freitas Netto et al., 2020). The former encompasses textual arguments that list ecological benefits of a product/service to create a deceptive environmental claim. The second refers to natureevoking elements, such as images using colors, sounds, or natural landscapes that might create false perceptions of the firm’s greenness (Parguel et al. 2015).

Despite previous studies that substantiate its negative outcomes, greenwashing consequences have not been conveniently addressed, and need to be further explored (Yang et al. 2020).

4.1 Theoretical approaches

Several theoretical approaches have been used, but scholars have traditionally linked greenwashing with its effect on stakeholders, based on five theories: the attribution theory (Chen et al. 2019; Farooq and Wicaksono 2021; Kahraman and Kazançoğlu 2019; Pizzetti et al. 2021; Szabo and Webster 2021), the attitude-behaviour-context (ABC) theory (Wang et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2018), theory of reasoned action (Bulut et al. 2021; Nguyen et al. 2021), the cognition-affect-behavior (C-A-B) paradigm (Nguyen et al. 2019; Rahman et al. 2015), and the affect–reason–involvement (ARI) model (Schmuck et al. 2018; Urbański and Ul Haque 2020). The attribution theory is the most widely used theoretical approach, with scholars arguing that immoral and irresponsible behaviors by firms, such as pursuing greenwashing, have several detrimental effects. For example, a lower intention to invest (Szabo and Webster 2021); a negative effect on consumer green trust (Chen et al. 2019), perceived risk, skepticism, and purchasing intention (Kahraman and Kazançoğlu 2019). Moreover, perceived greenwashing can have damaging results for organizations, in regard to consumers’ product and environmental perceptions, and happiness and website interactions as well (Szabo and Webster 2021).

4.2 Instruments

While examining previous studies, it was clear that they are essentially quantitatively based on surveys (Ahmad and Zhang 2020; Akturan 2018; Bulut et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2019, 2020; Chen and Chang 2013; De Jong et al. 2018; Guerreiro and Pacheco 2021; Hameed et al. 2021; Jog and Singhal 2020; Junior et al. 2019; Majláth 2017; Nguyen et al. 2019, 2021; Schmuck et al. 2018; Tahir et al. 2020; Testa et al. 2020; Urbański and Ul Haque 2020). This methodology may be justified by the high cost of conducting field experiments (Ferrón-Vílchez et al. 2021). There are, however, a few studies that used experiments (De Jong et al. 2018; Ferrón-Vílchez et al. 2021; Gatti et al. 2021; Guyader et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2018; Parguel et al. 2015; Pizzetti et al. 2021; Schmuck et al. 2018; Torelli et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020) and mix-method approaches (Szabo and Webster 2021).

4.3 Stakeholders

Several authors used samples of students in their research (Bulut et al. 2021; Ferrón-Vílchez et al. 2021; Guyader et al. 2017; Majláth 2017; Torelli et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). This choice might perhaps occur due to the lack of cooperation (by managers, for instance), and to the fact that students are also consumers or potential investors and are an “easy access” stakeholder for scholars. Employees of green organizations and consulting firms (Szabo and Webster 2021) and employees (low and mid-level management) (Tahir et al. 2020) were also investigated, as well as investors (Gatti et al. 2021; Pizzetti et al. 2021). Most of the analyzed studies, however, considered consumers (Ahmad and Zhang 2020; Chen et al. 2019, 2020; Chen and Chang 2013; De Jong et al. 2020; Guerreiro and Pacheco 2021; Hameed et al. 2021; Jog and Singhal 2020; Junior et al. 2019; Nguyen et al. 2019, 2021; Parguel et al. 2015; Rahman et al. 2015; Testa et al. 2020; Urbański and Ul Haque 2020). This means other relevant stakeholders have been neglected in the literature (Gatti et al. 2021; Szabo and Webster 2021).

4.4 Effects of greenwashing

Latest research on the effects of greenwashing on stakeholders suggests that these practices have detrimental effects on consumers, brands, and organizations. However, different forms/levels of greenwashing may have different effects on the stakeholders’ perceptions, and on their reactions towards environmental scandals (Torelli et al. 2020).

Studies have consistently showed that perceived greenwashing practices negatively affect consumers, whether directly or indirectly. For instance, greenwashing seems to influence consumer purchase intentions and behavior (Ahmad and Zhang 2020; Akturan 2018; Bulut et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2020; Guerreiro and Pacheco 2021; Guyader et al. 2017; Hameed et al. 2021; Jog and Singhal 2020; Junior et al. 2019; Kahraman and Kazançoğlu 2019; Nguyen et al. 2019; Urbański and Ul Haque 2020; Wang et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2018). In contrast, Urbański and Ul Haque found statistical evidence in their study that suggests that purchase intention is not affected by greenwashing (2020). Additionally, greenwashing inhibits consumers from making informed purchase decisions (Wu et al. 2020), as it increases consumers’ confusion (Chen and Chang 2013) and diminishes their willingness to pay for greenwashed products (Lee et al. 2018). These actions also influence negatively consumers’ evaluation of ads (Majláth 2017) and affect brand’s ecological image and brand attitude (Parguel et al. 2015). Consumer perceptions of risk (Chen and Chang 2013), skepticism (Kahraman and Kazançoğlu 2019; Nguyen et al. 2019), green trust (Chen and Chang 2013; Guerreiro and Pacheco 2021), green WOM (Guerreiro and Pacheco 2021; Nguyen et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2018), are also impacted by greenwashing.

Studies have also highlighted the negative influence of greenwashing on brands. Green brand associations, brand credibility, green brand equity (Akturan 2018), green brand image, green brand loyalty (Chen et al. 2020; Hameed et al. 2021), green brand love (Hameed et al. 2021), customer brand engagement (Guerreiro and Pacheco 2021) are also affected by greenwashing. Increased greenwashing deteriorates the company’s green brand as well (Pimonenko et al. 2020).

Greenwashing also presents undesired outcomes for firms. Higher levels of greenwashing lead to a decrease in intention to invest, and a higher level of blame attribution (Pizzetti et al. 2021). Furthermore, Gatti et al. (2021) demonstrated that investors are less prone to invest in companies that practice greenwashing, than in firms that exhibit corporate misbehavior unrelated to misleading communication. Additionally, studies suggest that when greenwashing activities grow, managers are less willing to collaborate with the greenwasher (Ferrón-Vílchez et al. 2021).

Research also showed that greenwashing has a spillover effect, meaning that greenwashing practices of one brand negatively affect consumers’ intention to purchase other brands in the same industry (H. Wang et al. 2020). Consumers make an overall judgement on other firms, even if they produce genuine natural products (Kahraman and Kazançoğlu 2019).

Considering all the negative outcomes derived from greenwashing practices, some authors set out to investigate what the consequences of restraining greenwashing might be. These authors defend that even if greenwashing were regulated, the cost associated with CSR practices or the environmental subject is not very important to firms, so it may not lead them to act green. In contrast, if greenwashing practices were allowed, it might incentivize firms to behave in a genuinely green manner. Even so, perceived corporate greenwashing can have harmful consequences for organizations, in relation to their consumers’ product and environmental perceptions (Szabo and Webster 2021). Greenwashing poses a major threat and does not offer a true competitive advantage (De Jong et al. 2018), as corporate greenwashing can have negative effects on corporate financial performance (Testa et al. 2018) and their green brand (Pimonenko et al. 2020). Hence, only genuine green conduct will have the desired positive effects (De Jong et al. 2020) on the various stakeholders.

5 Future research directions

Understanding which the latest trends of research are, on greenwashing and its effect on stakeholders, sheds light on future research directions. For that purpose, we have considered 24 articles that had been published in the last three years (2019–2021) (see Table 7), uncovering gaps and suggestions for future research.

From the articles reviewed, four thematic lines were identified that present research opportunities. The first investigation opportunity comprises greenwashing impacts on brands and how they are perceived. Thus, future research could discuss the differences of greenwashing and its effect on green brand image (Chen et al. 2020), namely, on the trust in an ecolabel as well as its perceived self-efficacy (Testa et al. 2020). Briefly, the connection between greenwashing and green brand should be better understood (Pimonenko et al. 2020).

The second opportunity is related to consumer attitudes towards corporate greenwashing, mainly on their purchase intention. Scholars suggest the inclusion of three aspects in future studies: consumers’ individual characteristics, product, and business-related aspects. Individual aspects such as consumer trust (Hameed et al. 2021), cognitive ability (Wang et al. 2020), environmental consciousness level (Chen et al. 2019), environmental knowledge, price sensitivity, income and online experiences (Ahmad and Zhang 2020) deserve to be included in the studies of greenwashing effect on consumer green purchase intention. However, consumers’ different perceptions of greenwashing might have a different importance/effect on green purchasing behavior (Wang et al. 2020). Product-associated variables are often referred to as a relevant aspect to delve into the greenwashing literature and its effects on consumer attitudes and intentions. Within the scope of the greenwashing effect on consumer purchase intention, a comparison between regular products and green ones is often recommended (Chen et al. 2020; Hameed et al. 2021). These differences could include product attributes such as price, quality, accessibility (Guerreiro and Pacheco 2021), labels or packaging (Testa et al. 2020). Additionally, consumer green purchase intention studies might be applied in a broader range of product categories (Akturan 2018; Nguyen et al. 2019, 2021), such as high-involvement products (Schmuck et al. 2018); electronics, fast food (Topal et al. 2020) or beverages (Jog and Singhal 2020). Bulut et al. suggested an investigation of post-millennials’ green purchasing tendencies, exploring why and what the preferences of product categories of these specific stakeholders are (Bulut et al. 2021). Finally, business aspects such the company (De Jong et al. 2018) or even company’s sectors (Kahraman and Kazançoğlu 2019), the trademark (Nguyen et al. 2021), company brands, ownership type (Nguyen et al. 2019), could also be related to consumer reactions to the greenwashing phenomenon. Thus, future investigations can take these aspects into account.

The third opportunity refers to B2B relationships, which have seldom been investigated. Several studies have assessed the perception of consumers relating to corporate greenwashing practices, neglecting the points of view of other stakeholders. Thus, using other categories of stakeholders besides consumers (Torelli et al. 2020), such as employees, organizational customers, suppliers or B2B relationships could be investigated (Gatti et al. 2021; Pizzetti et al. 2021). In this way, future studies may seek to understand the perception of other stakeholders involved, directly or indirectly, in greenwashing practices, providing a broader approach to environmental irresponsible/immoral practices.

The last opportunity for future research consists of defining a taxonomy in greenwashing to set the different practices. The different levels of greenwashing practices require the development and validation of new scales, as their impacts might differ depending on the perceived severity of the action (Torelli et al. 2020). Future research could discuss the differences of greenwashing activities (Chen et al. 2020) and develop an adequate measurement of these practices (Zhang et al. 2018), by adding other levels of misleading environmental communication, factors, types or concepts of greenwashing proposed by previous authors (Pizzetti et al. 2021; Torelli et al. 2020). This aspect presents a fertile field in sustainability and marketing research, as the refinement of the actual classification levels of greenwashing will enrich and more comprehensively express the multidimensional character of greenwashing.

Most of the authors also suggest other methodologies/instruments (Chen et al. 2020; Topal et al. 2020), with other respondents (Gatti et al. 2021; Tahir et al. 2020), different scales (Urbański and Ul Haque 2020) and the collection of longitudinal data (Chen et al. 2020; Hameed et al. 2021; Tahir et al. 2020). The replication of the author’s proposed model in other countries is also frequent (Bulut et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2020; Hameed et al. 2021). The researched literature allowed us to identify themes that are in evidence, with accentuated growth, representing research contexts and potential fields to be developed.

6 Final considerations

There are past studies, bibliometric analyses, and systematic reviews regarding greenwashing. However, they did not provide a detailed analysis of the impact of these practices on stakeholders. This study originally provides a closer look of these aspects, expanding the scientific knowledge of the subject.

This investigation provides information on the state of the art, recognizing trends, gaps, and future research opportunities, thus, contributing to the existing body of knowledge. Through the bibliometric analysis of the relevant articles focusing on greenwashing, published up to 2021, and a narrower literature on the articles that investigate the effects of greenwashing on stakeholders, published in the last three years, it presents 3 major contributions: First, it is possible to see the evolution of greenwashing literature. The increase of published articles over the years indicates how relevant and novel this research topic is for the academia and for managers, which also demonstrates the potential to deepen the subject in other fields. Besides, the trends, most prolific authors, articles, and journals were identified. As a result, it is possible to acknowledge the leading journals that are specialized in greenwashing studies, the countries, the authors, and articles that contribute most to greenwashing literature and knowledge dissemination. It is also possible to realize that there is a recent investigation trend on greenwashing outcomes, that is in the perceptions of this practice, skepticism, purchase intention, trust, and word of mouth. In addition, the use of VOSviewer software enabled the presentation of a network of co-occurrences of keywords through maps, which made it possible to identify hotspots and trends in the research topics that are crucial for understanding advances in the field, and, thus, providing topics that can be further explored. In turn, the literature review, covering articles that relate greenwashing to stakeholders, allowed to identify that attribution theory is the most used theoretical approach, and that previous investigations are largely based on surveys. Even if stakeholders, in general, are the focus of this investigation, we always end up on customers: as most articles investigate greenwashing from the consumers’ point of view. Students are also often used as a proxy for these external stakeholders. All the same, employees and investors are also scrutinized. Nevertheless, relevant stakeholders have been neglected in the literature (Gatti et al. 2021; Szabo and Webster 2021), which can be the reason why there are several calls on this aspect (Gatti et al. 2021; Pizzetti et al. 2021; Torelli et al. 2020). Moreover, past literature on the effects of greenwashing on stakeholders indicates that these practices have several damaging effects on consumers, brands, and organizations. Finally, by analyzing the latest research, this investigation was able to identity gaps that can be used in future investigations. Thus, several branches of investigation emerge. Future research might deepen the studies regarding greenwashing impacts on branding, on consumer purchase intentions and attitudes, on other stakeholders and B2B relationships and finally on delineating a taxonomy in greenwashing to set the difference on the different practices. Hence, the most relevant contribution of this study is the identification and analysis of the past, present and future areas to research. Above all, the results of this study make it clear that misleading claims regarding environmental practices inflict harm on stakeholders. Thus, it raises awareness of the damaging effects, which might help to reduce the frequency of these acts.

6.1 Limitations

This study, as all other bibliometric analysis and literature reviews, is subject to several limitations. First, the articles were downloaded on a specific date from a single database. Despite WoS being the most reliable data source (Saleem et al. 2021), the authors acknowledge that additional relevant papers might be indexed in other databases, thus, there is the possibility that some might have been missing in this analysis. Therefore, other databases (i.e., Scopus) could be consulted to help avoid eventual data bias and to better understand greenwashing research. Additionally, despite the concern to include all possible key terms to search the articles for the study, it is possible that some terms related to stakeholders might be missing. Second, the authors decided to analyze only articles and disregard other works such as book chapters, proceedings papers, early access, editorial materials, etc. However, the chosen articles, published in journals, represent qualified knowledge as they are peer-reviewed. Third, the literature review was based on the number of citations and the last three years, regardless of the actual quality of the document. However, the number of citations is more significant than the number of articles, because it is a better approach to the author’s impact and influence (Podsakoff et al. 2008). Finally, other analysis techniques can be used to obtain more comprehensive results.

Data Availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Ahmad W, Zhang Q (2020) Green purchase intention: Effects of electronic service quality and customer green psychology. J Clean Prod 267:122053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122053

Akturan U (2018) How does greenwashing affect green branding equity and purchase intention? An empirical research. Mark Intell Plann 36(7):809–824. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-12-2017-0339

Andreoli TP, Crespo A, Minciotti S (2017) What has been (short) written about greeenwashing: a bibliometric research and a critical analysis of the articles found regarding this theme. Revista de Gestao Social e Ambiental 11(2):54–72. https://doi.org/10.24857/rgsa.v11i2.1294

Booth P, Chaperon SA, Kennell JS, Morrison AM (2020) Entrepreneurship in island contexts: A systematic review of the tourism and hospitality literature. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85(November 2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102438

Bulut C, Nazli M, Aydin E, Haque AU (2021) The effect of environmental concern on conscious green consumption of post-millennials: the moderating role of greenwashing perceptions. Young Consumers 22(2):306–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-10-2020-1241

Chen H, Bernard S, Rahman I (2019) Greenwashing in hotels: a structural model of trust and behavioral intentions. J Clean Prod 206:326–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.168

Chen Y-S, Chang C-H (2013) Greenwash and Green Trust: the Mediation Effects of Green Consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J Bus Ethics 114(3):489–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1360-0

Chen Y-S, Huang A-F, Wang T-Y, Chen Y-R (2020) Greenwash and green purchase behaviour: the mediation of green brand image and green brand loyalty. Total Qual Manage Bus Excellence 31(1–2):194–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2018.1426450

Chen YS, Lin CL, Chang CH (2014) The influence of greenwash on green word-of-mouth (green WOM): the mediation effects of green perceived quality and green satisfaction. Qual Quantity 48(5):2411–2425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-013-9898-1

Contreras-Pacheco OE, Talero-Sarmiento LH, Camacho-Pinto JC (2019) Effects of corporate social responsibility on employee organizational identification: authenticity or fallacy. Contaduría y Administración 64(4):1–22. https://doi.org/10.22201/fca.24488410e.2018.1631

Dabić M, Maley J, Dana LP, Novak I, Pellegrini MM, Caputo A (2020) Pathways of SME internationalization: a bibliometric and systematic review. Small Bus Econ 55(3):705–725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00181-6

Dangelico RM, Vocalelli D (2017) “Green Marketing”: an analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. J Clean Prod 165:1263–1279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.184

de Netto F, Sobral SV, Ribeiro MFF, A. R. B., Soares GR (2020) da L. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: a systematic review. Environmental Sciences Europe, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-0300-3

De Jong MDT, Harkink KM, Barth S (2018) Making Green Stuff? Effects of Corporate Greenwashing on Consumers. J Bus Tech Communication 32(1):77–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651917729863

De Jong MDT, Huluba G, Beldad AD (2020) Different shades of Greenwashing: consumers’ reactions to environmental lies, Half-Lies, and Organizations taking credit for following legal obligations. J Bus Tech Communication 34(1):38–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651919874105

de Oliveira OJ, da Silva FF, Juliani F, Barbosa LCFM, Nunhes TV (2019) Bibliometric Method for Mapping the State-of-the-Art and Identifying Research Gaps and Trends in Literature: An Essential Instrument to Support the Development of Scientific Projects. In IntechOpen

Delmas MA, Burbano VC (2011) The drivers of greenwashing. Calif Manag Rev 54(1):64–87. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64

Denyer D, Tranfield D (2009) Producing a systematic review. In: Buchanan DA, Bryman A (eds) The SAGE handbook of Organizational Research Methods. Sage Publications Ltd., pp 671–689

Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM (2021) How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res 133(May):285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

Drejerska N, Chrzanowska M, Wysoczański J (2023) Cash transfers and female labor supply — how public policy matters ? A bibliometric analysis of research patterns. Quality & Quantity, 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01609-0

Farooq Y, Wicaksono H (2021) Advancing on the analysis of causes and consequences of green skepticism. J Clean Prod 320(February):128927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128927

Ferrón-Vílchez V, Valero-Gil J, Suárez-Perales I (2021) How does greenwashing influence managers’ decision-making? An experimental approach under stakeholder view. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 28(2):860–880. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2095

Font X, Walmsley A, Cogotti S, McCombes L, Häusler N (2012) Corporate social responsibility: the disclosure-performance gap. Tour Manag 33(6):1544–1553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.012

Frerichs IM, Teichert T (2023) Research streams in corporate social responsibility literature: a bibliometric analysis. Manage Rev Q 73:231–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-021-00237-6

Gatti L, Pizzetti M, Seele P (2021) Green lies and their effect on intention to invest. J Bus Res 127:228–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.028

Gatti L, Seele P, Rademacher L (2019) Grey zone in – greenwash out. A review of greenwashing research and implications for the voluntary-mandatory transition of CSR. Int J Corp Social Responsib 4(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-019-0044-9

Grant MJ, Booth A (2009) A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J 26(2):91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Guerreiro J, Pacheco M (2021) How green trust, consumer brand engagement and green word-of-mouth mediate purchasing intentions. Sustainability 13(14):1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147877

Guyader H, Ottosson M, Witell L (2017) You can’t buy what you can’t see: retailer practices to increase the green premium. J Retailing Consumer Serv 34:319–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.07.008

Hahn R, Lülfs R (2014) Legitimizing negative aspects in GRI-Oriented sustainability reporting: a qualitative analysis of Corporate Disclosure Strategies. J Bus Ethics 123(3):401–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1801-4

Hameed I, Hyder Z, Imran M, Shafiq K (2021) Greenwash and green purchase behavior: an environmentally sustainable perspective. Environ Dev Sustain 23:13113–13134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01202-1

Jog D, Singhal D (2020) Greenwashing understanding among indian consumers and its impact on their green consumption. Global Bus Rev 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920962933

Juliani F, Oliveira OJ, De (2016) International Journal of Information Management State of research on public service management: identifying scientific gaps from a bibliometric study. Int J Inf Manag 36(6):1033–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.07.003

Junior SB, Martínez MP, Correa CM, Moura-Leite RC, da Silva D (2019) Greenwashing effect, attitudes, and beliefs in green consumption. RAUSP Manage J 54(2):226–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-08-2018-0070

Kahraman A, Kazançoğlu İ (2019) Understanding consumers’ purchase intentions toward natural-claimed products: a qualitative research in personal care products. Bus Strategy Environ 28(6):1218–1233. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2312

Kim J, Fairclough S, Dibrell C (2017) Attention, Action, and Greenwash in Family-Influenced Firms? Evidence from Polluting Industries. Organ Environ 30(4):304–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026616673410

Kirchhoff S (2000) Green business and blue angels: a model of voluntary overcompliance with asymmetric information. Environ Resource Econ 15(4):403–420. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008303614250

Kraus S, Breier M, Dasí-Rodríguez S (2020) The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int Entrepreneurship Manage J 16(3):1023–1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00635-4

Laufer WS (2003) Social accountability and corporate Greenwashing. J Bus Ethics 43(3):253–261. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022962719299

Lee HCB, Cruz JM, Shankar R (2018) Corporate social responsibility (CSR) issues in Supply Chain Competition: should Greenwashing be regulated? Decis Sci 49(6):1088–1115. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12307

Lee J, Bhatt S, Suri R (2018) When consumers penalize not so green products. Psychol Mark 35(1):36–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21069

Lyon TP, Maxwell JW (2011) Greenwash: corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J Econ Manage Strategy 20(1):3–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2010.00282.x

Lyon TP, Montgomery AW (2015) The Means and End of Greenwash. Organ Environ 28(2):223–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026615575332

Mahoney LS, Thorne L, Cecil L, LaGore W (2013) A research note on standalone corporate social responsibility reports: signaling or greenwashing? Crit Perspect Acc 24(4–5):350–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2012.09.008

Majláth M (2017) The Effect of Greenwashing Information on ad evaluation. Eur J Sustainable Dev 6(3):92–104. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2017.v6n3p92

Montero-Navarro A, González-Torres T, Rodríguez-Sánchez JL, Gallego-Losada R (2021) A bibliometric analysis of greenwashing research: a closer look at agriculture, food industry and food retail. Br Food J 123(13):547–560. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-06-2021-0708

Moya-Clemente I, Ribes-Giner G, Chaves-Vargas JC (2021) Sustainable entrepreneurship: an approach from bibliometric analysis. J Bus Econ Manage 22(2):297–319. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2021.13934

Musgrove C (Casey), Choi F, P., Chris Cox K (eds) (2018) Consumer Perceptions of Green Marketing Claims: An Examination of the Relationships with Type of Claim and Corporate Credibility. Services Marketing Quarterly, 39(4), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332969.2018.1514794

Nguyen TTH, Nguyen KO, Cao TK, Le VA (2021) The impact of corporate Greenwashing Behavior on Consumers’ purchase intentions of Green Electronic Devices: an empirical study in Vietnam. J Asian Finance Econ Bus 8(8):229–240. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no8.0229

Nguyen TTH, Yang Z, Nguyen N, Johnson LW, Cao TK (2019) Greenwash and green purchase intention: the mediating role of green skepticism. Sustain (Switzerland) 11(9):1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092653

Nyilasy G, Gangadharbatla H, Paladino A (2014) Perceived Greenwashing: the interactive Effects of Green Advertising and Corporate Environmental performance on consumer reactions. J Bus Ethics 125(4):693–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1944-3

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, Mcdonald S, …, Mckenzie JE (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ 372(160). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Parguel B, Benoît-Moreau F, Larceneux F (2011) How sustainability ratings might deter ‘Greenwashing’: a closer look at ethical corporate communication. J Bus Ethics 102(1):15–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0901-2

Parguel B, Benoit-Moreau F, Russell CA (2015) Can evoking nature in advertising mislead consumers? The power of ‘executional greenwashing. ’ Int J Advertising 34(1):107–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2014.996116

Pimonenko T, Bilan Y, Horák J, Starchenko L, Gajda W (2020) Green brand of companies and greenwashing under sustainable development goals. Sustain (Switzerland) 12(4):1–15

Pizzetti M, Gatti L, Seele P (2021) Firms talk, suppliers walk: analyzing the locus of Greenwashing in the blame game and introducing ‘Vicarious greenwashing’. J Bus Ethics 170(1):21–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04406-2

Pizzi S, Caputo A, Corvino A, Venturelli A (2020) Management research and the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs): a bibliometric investigation and systematic review. J Clean Prod 276:124033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124033

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP, Bachrach DG (2008) Scholarly influence in the field of management: a bibliometric analysis of the determinants of University and author impact in the management literature in the past quarter century. J Manag 34(4):641–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308319533

Rahman I, Park J, Chi CGQ (2015) Consequences of “greenwashing”: consumers’ reactions to hotels’ green initiatives. Int J Contemp Hospitality Manage 27(6):1054–1081. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2014-0202

Saleem F, Khattak A, Ur Rehman S, Ashiq M (2021) Bibliometric analysis of Green Marketing Research from 1977 to 2020. Publications 9(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9010001

Schmuck D, Matthes J, Naderer B (2018) Misleading consumers with Green Advertising? An affect–reason–involvement account of Greenwashing Effects in Environmental Advertising. J Advertising 47(2):127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2018.1452652

Szabo S, Webster J (2021) Perceived Greenwashing: the Effects of Green Marketing on Environmental and product perceptions. J Bus Ethics 171(4):719–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04461-0

Tahir R, Athar MR, Afzal A (2020) The impact of greenwashing practices on green employee behaviour: mediating role of employee value orientation and green psychological climate. Cogent Bus Manage 7(1):1781996. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1781996

Tallon PP, Queiroz M, Coltman T, Sharma R (2019) Information Technology and the search for Organizational agility: a systematic review with Future Research possibilities. J Strategic Inform Syst 28(2):218–237

Testa F, Iovino R, Iraldo F (2020) The circular economy and consumer behaviour: the mediating role of information seeking in buying circular packaging. Bus Strategy Environ 29(8):3435–3448

Testa F, Miroshnychenko I, Barontini R, Frey M (2018) Does it pay to be a greenwasher or a brownwasher? Bus Strategy Environ 27(7):1104–1116. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2058

Topal İ, Nart S, Akar C, Erkollar A (2020) The effect of greenwashing on online consumer engagement: a comparative study in France, Germany, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. Bus Strategy Environ 29(2):465–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2380

Torelli R, Balluchi F, Lazzini A (2020) Greenwashing and environmental communication: Effects on stakeholders’ perceptions. Bus Strategy Environ 29(2):407–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2373

Urbański M, Ul Haque A (2020) Are you environmentally conscious enough to differentiate between greenwashed and sustainable items? A global consumers perspective. Sustain (Switzerland) 12(5):1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051786

van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2010) Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84(2):523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Wang D, Walker T, Barabanov S (2020) A psychological approach to regaining consumer trust after greenwashing: the case of chinese green consumers. J Consumer Mark 37(6):593–603

Wang H, Ma B, Bai R (2020) The spillover effect of greenwashing behaviours: an experimental approach. Mark Intell Plann 38(3):283–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-01-2019-0006

Wu M-W, Shen C-H (2013) Corporate social responsibility in the banking industry: motives and financial performance. J Bank Finance 37(9):3529–3547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.04.023

Wu Y, Zhang K, Xie J (2020) Bad Greenwashing, Good Greenwashing: corporate social responsibility and information transparency. Manage Sci 66(7):3095–3112. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2019.3340

Yang Z, Nguyen TTH, Nguyen HN, Nguyen TTN, Cao TT (2020) Greenwashing behaviours: causes, taxonomy and consequences based on a systematic literature review. J Bus Econ Manage 21(5):1486–1507. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2020.13225

Zhang L, Li D, Cao C, Huang S (2018) The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: the mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern. J Clean Prod 187:740–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.201

Funding

This work has received national funding support from the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., Project UI/BD/150962/2021, Project UIDB/05037/2020, and Project UIDB/04928/2020.

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection analysis and first draft were performed by CS. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and contributed to its final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Santos, C., Coelho, A. & Marques, A. A systematic literature review on greenwashing and its relationship to stakeholders: state of art and future research agenda. Manag Rev Q (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00337-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00337-5