Abstract

In this work, we make a distinction between the differential geometric notion of an isometry relationship among two dimensional surfaces embedded in three-dimensional point space and the continuum mechanical notion of an isometric deformation of a two dimensional material surface. We illustrate the importance of separating the abstract theory of surfaces in differential geometry and their related differential geometric features from the physical notion of a material surface which is subject to a deformation from a given reference configuration. In differential geometry, while two surfaces may be isometric, the mapping between them that characterizes the isometry is simply a mapping between the points of the surfaces and not necessarily between corresponding material particles of a single deformed material surface.

We review two equivalent characterizations of a smooth isometric deformation of a flat material surface into a curved surface, and emphasize the requirement that the referential directrix and rulings, and their deformed counterparts, must provide a basis for establishing a complete curvilinear coordinate covering of the material surface in both the reference and deformed states. Because this covering requirement has been overlooked in recent publications concerning the isometric bending of ribbons, we illustrate its importance in properly defining the deformation of a ribbon in the two examples of a flat rectangular material strip that is isometrically deformed into either (i) a portion of a circular cylindrical surface, or (ii) a portion of a circular conical surface. We then show how the accurate calculation of the bending energy in these two examples is influenced by this oversight. In example (i), the curvature along the generators of the deformed surface, generally helical in form, is constant. In this special circumstance overlooking the covering requirement, as has been done in the literature by integrating the specific bending energy, dependent only on the curvature, over a domain on the supporting circular cylindrical surface equal in area, though not equal in geometric form, to that of the deformed ribbon, gives the correct bending energy result. In example (ii), the curvature along a generator of the cone is not constant and the calculation of the bending energy is, indeed, compromised by this oversight.

The historically important dimensional reductions that Sadowsky and Wunderlich introduced to study the bending energy and the equilibrium configurations of isometrically deformed rectangular strips have gained classical notoriety within the subject of elastic ribbons and Möbius bands. We show that the Sadowsky and Wunderlich functionals also overlook the covering requirement and that the exact bending energy is underestimated by these functionals, the Sadowsky functional being the lowest. We then show that the error in using these functionals can be great for a rectangular strip of given length \(\ell\) and width \(w\), depending on the form of the isometric deformation and the size of the half-length-to-width ratio \(w/2\ell\). The Sadowsky functional is meant to apply to strips for which \(w/2\ell\) is sufficiently small, in which case the covering requirement is of little consequence, and for such strips it yields an acceptable approximation of the actual bending energy. In such cases the Wunderlich functional shows only an incremental improvement over the Sadowsky calculation. While the Wunderlich functional is meant to apply accurately for all strips, without restricting the size of \(w/2\ell\), we show that in overlooking the covering requirement it greatly underestimates the actual bending energy for many isometrically deformed ribbons. In particular, we show relative errors between the exact, the Wunderlich, and the Sadowsky calculations of the bending energy as a function of \(w/2\ell\) for the case of a rectangular strip which is isometrically deformed into a portion of a right circular conical surface, and we observe that the error in approximating the exact bending energy by the Wunderlich functional for reasonable ratios \(w/2\ell\) is large and unacceptable. We then give an example of the isometric deformation of a rectangular strip whose Wunderlich functional predicts zero bending energy but for which the exact bending energy can be as large as one pleases.

Finally, contrary to suggestions in the literature, we argue that Kirchhoff rod theory does not generally apply to the study of the isometric deformation of a thin rectangular strip because for this class of problems the through thickness dimension of the strip is assumed to be infinitesimal as compared to its width \(w\). For Kirchhoff rod theory to apply, these dimensions must be comparable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In classical continuum mechanics, a body ℬ may be viewed, geometrically, as a compact three-dimensional Riemannian manifold endowed with a Riemannian metric. A configuration of a body makes an identification between each body element \(x\) belonging to ℬ and a point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in a subset \({\mathcal{R}}_{*}\) of three-dimensional Euclidean point space \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\). In this setting, \({\mathcal{R}}_{*}\) is called the reference configuration of the body. A (smooth) deformation of the ‘body’ from \({\mathcal{R}}_{*}\) to some other subset ℛ of \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\) is then a mapping \(\boldsymbol{x}\mapsto\boldsymbol{y}\), where \(\boldsymbol{y}\) denotes a generic element of ℛ. In this setting, ℛ is called the spatial (or deformed) configuration of the body. A deformation is isometric if lengths between all points in \({\mathcal{R}}_{*}\) and corresponding points in ℛ are preserved under the mapping. Because a body cannot generally be embedded in \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\), a three-dimensional Euclidean observer cannot discern its geometrical structure without recourse to special instruments.

An analogous level of clarity is absent from a significant portion of the literature concerned with ribbons and sheets conceived of as two-dimensional bodies, which we refer to as material surfaces. The difference between the abstract mathematical notion of a surface in two-dimensional Euclidean point space \(\mathbb{E}^{2}\) and its embedding into \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\) and the physical notion of the configuration of a material surface as viewed in \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\) appears to have gone unappreciated in much of the literature dealing with configurations of ribbons and sheets in \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\).

As an abstract mathematical entity, a material surface \({\mathcal{P}}\) may be considered, geometrically, to be a compact two-dimensional manifold endowed with a Riemannian metric. On this basis, an isometry between two distinct material surfaces can be defined and studied. A configuration of a material surface \({\mathcal{P}}\) rests on an identification between each element \(x\) of \({\mathcal{P}}\) and a point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in a subset \({\mathcal{D}}\) of \(\mathbb{E}^{2}\); \({\mathcal{D}}\) is called the reference configuration of the material surface. A (smooth) deformation of the ‘material surface’ from \({\mathcal{D}}\) to \({\mathcal{S}}\) is then a mapping \(\boldsymbol {x}\mapsto\boldsymbol{y}\), where \(\boldsymbol{y}\) is an element of \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\). In this setting, \({\mathcal{S}}\) is called the spatial (or deformed) configuration of the material surface. A deformation from \({\mathcal{D}}\) to \({\mathcal{S}}\) is isometric if the length of any curve of points in \({\mathcal{D}}\) is preserved under the mapping. This stands in contrast to the prevailing view in classical differential geometry, where two surfaces are said to be isometric if they have the same Gaussian curvature at corresponding points and, in particular, a curved surface that is isometric to a planar region must be developable.

What perhaps makes things confusing when considering material surfaces and three-dimensional bodies is that, because of the embedding property, the Riemannian manifold and configurations of a material surface can be discerned by a three-dimensional Euclidean observer. Unless special care is taken in defining an isometry between two surfaces and an isometric deformation of a material surface, the distinction may therefore be easily missed. In particular, the pitfall of misconstruing the notion (and condition) of conservation of Gaussian curvature as the constraint appropriate to characterizing an unstretchable (or inextensional) two-dimensional body must be avoided.

We explain below, by analogy and at a reasonably fundamental level, our understanding of why much of the literature on unstretchable material surfaces is marred by confusion surrounding the distinction between the isometric deformation of a material surface and the differential geometric idea of an isometry between two surfaces. Section 2 is devoted to background. Drawing on the work of Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1], we define precisely what we mean by a smooth isometric deformation of a flat material surface into a curved surface, provide two equivalent conditions that are necessary and sufficient that a deformation of a flat material surface to a curved surface is isometric, and highlight the roles of the geometric objects central to our description. Most crucial among these are the referential and spatial directrices and the referential rulings and the spatial generators, which together provide a basis for establishing meaningful correspondences between parametrizations of the material surface in its reference and deformed configurations. In Sect. 3, we study a class of mappings introduced by Dias and Audoly [2] and show that all such mappings are isometric in the sense defined in Sect. 2. In Sect. 4, we consider issues that arise in connection with parametrizations of the reference and deformed configurations of a material surface. These issues hinge on the importance of ensuring a surjective correspondence between material points and parameter pairs. Dias and Audoly [2] overlook this issue and we find that their approach yields a complete covering of the referential and deformed surfaces only in the simple degenerate case where the reference configuration of the material surface is rectangular and is deformed into a (not necessarily circular) right cylindrical ring. Moreover, we discover that the “edge functions” of Dias and Audoly [2] fail to cure this difficulty. In Sect. 5 we explore how calculations of bending energy may be affected by failing to ensure a surjective correspondence between material points and parameter pairs. To illustrate our point, we compute the bending energy for a rectangular material strip bent to conform to a portion of a right circular conical surface. We then compare that energy to the analogous energy obtained by evaluating Wunderlich’s [3, 4] dimensionally-reduced energy functional, proving that that functional is strictly bounded above by the bending energy. We also find that Wunderlich’s [3, 4] functional provides an accurate estimate of the bending energy only in the limit in which the half-width-to-length ratio of the strip is infinitesimal and that Sadowsky’s [5, 6] functional performs just as well as Wunderlich’s [3, 4] in that regime. This stems from the absence of a surjective correspondence between material points and parameters that is inherent to the parametric approach employed by Wunderlich [3, 4] and those who have emulated his work or utilized his functional. In Sect. 6, we consider the implications of a key assumption in the theory of Kirchhoff rods, namely the assumption that the cross sections of such a rod are rigid and, thus, in particular, cannot sustain in-plane deformations. Observing that the theory of Dias and Audoly [2] violates this assumption, we argue that their theory applies only to strip-like bodies that have widths comparable to their thicknesses and, thus, to Kirchhoff rods with infinitesimal cross sectional area or framed curves. Finally, in Sect. 7, we discuss and summarize our findings.

2 Preliminaries

Consider a material surface that is identified with an open, connected subset \({\mathcal{D}}\) of two-dimensional Euclidean point space \(\mathbb {E}^{2}\). Suppose that \({\mathcal{D}}\) is deformed isometrically into a surface \({\mathcal{S}}\) in three-dimensional point space \(\mathbb {E}^{3}\). Let \(\{\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1},\boldsymbol{\imath}_{2}\}\) be a fixed, positively oriented, orthonormal basis for the translation space \(\mathbb{V}^{2}\) of \(\mathbb{E}^{2}\) and define \(\boldsymbol {\imath}_{3}:=\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1}\times\boldsymbol{\imath}_{2}\) so that \(\{\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1},\boldsymbol{\imath}_{2},\boldsymbol {\imath}_{3}\}\) is a fixed, positively oriented, orthonormal basis for the translation space \(\mathbb{V}^{3}\) of \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\).

2.1 Deformations

Following Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1], \({\mathcal{D}}\) can be represented in terms of a referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) and a family of referential rulings that do not intersect in the interior of \({\mathcal{D}}\). Let \(\hat{\boldsymbol{x}}_{0}\) be an arclength parametrization of \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\). It is then useful to view \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) as a curve framed by a moving orthonormal triad \(\{ \boldsymbol{l}_{1},\boldsymbol{l}_{2},\boldsymbol{l}_{3}\}\) with elements

where a prime denotes differentiation with respect to arclength, and to express the orientation of a generic referential ruling by a unit vector field

where \(\nu\) measures the tangent of the angle between \(\boldsymbol {l}_{1}\) and the rulings. With the foregoing provisions, each point \(\boldsymbol{x}\in{\mathcal{D}}\subset\mathbb{E}^{2}\) can be expressed in terms of arclength \(\alpha\) along \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) and position \(\beta\) along the rulings through a relation \(\boldsymbol {x}=\hat{\boldsymbol{x}}(\alpha,\beta)\) with \(\hat{\boldsymbol{x}}\) of the formFootnote 1

The directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) is not necessarily a subset of \({\mathcal{D}}\). Indeed, for \((\alpha, \beta)\) to cover \({\mathcal {D}}\), \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) must generally contain segments that are disjoint from \({\mathcal{D}}\).Footnote 2 It is therefore overly restrictive to identify the referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) with a material curve in \({\mathcal{D}}\).

The surface \({\mathcal{S}}\) admits a representation analogous to that of the flat region \({\mathcal{D}}\). In particular, the spatial directrix \({\mathcal{C}}\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) is the image of the referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) and has arclength parametrization \(\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}_{0}\) satisfying

for some rotation field \(\boldsymbol{R}\). Additionally, the generators of \({\mathcal{S}}\) are determined simply by rotating the rulings of \({\mathcal{D}}\) under \(\boldsymbol{R}\), so that the generator \(\boldsymbol{a}\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) corresponding to a referential ruling with orientation \(\boldsymbol{b}\) is given by

In view of (2.4) and (2.5), the point \(\boldsymbol {y}\) on \({\mathcal{S}}\) corresponding to the point \(\boldsymbol{x}=\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}(\alpha,\beta)\) on \({\mathcal{D}}\) is determined by a relation \(\boldsymbol{y}=\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}(\alpha,\beta)\), with \(\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}\) being of the form

Since, as observed earlier, \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) must generally include segments that are disjoint from \({\mathcal{D}}\), a continuity argument leads to the conclusion that \({\mathcal{C}}\) must generally contain segments that are disjoint from \({\mathcal{S}}\).

Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1] emphasize that the mappings defined in (2.3) and (2.6) are not meaningful unless each pair \((\alpha,\beta)\) corresponds to a unique material point \(\boldsymbol {x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) and the underlying correspondence between such coordinate pairs and points provides a complete covering of \({\mathcal{D}}\). Granted that these requirements are met, there exist scalar-valued mappings \(\tilde{\alpha}\) and \(\tilde{\beta}\) defined on \({\mathcal {D}}\) and a mapping \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{x}}\) from \({\mathcal{D}}\) to itself such that

for each \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\). Moreover, \(\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}\) defined by

constitutes a deformation from \({\mathcal{D}}\) to \({\mathcal{S}}\).

Let \(\nabla\) denote the gradient with respect to position \(\boldsymbol {x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) and note that the dual basis vectors \(\boldsymbol{g}^{1}\) and \(\boldsymbol{g}^{2}\) are given by

Then, since

and

we see that a deformation \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{y}}\) from \({\mathcal{D}}\) to \({\mathcal{S}}\) defined through (2.3) and (2.6) in accord with (2.8) is isometric—in the sense that it preserves the length of any material curve in \({\mathcal{D}}\)—only if both of the following conditions hold:

-

There exist mappings \(\tilde{\alpha}\) and \(\tilde {\beta}\) such that each point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) and its image \(\boldsymbol{y}\) on \({\mathcal{S}}\) obey (2.7) and (2.8), where \(\hat{\boldsymbol{x}}\) and \(\hat {\boldsymbol{y}}\) are as defined in (2.3) and (2.6).

-

The partial derivatives of \(\hat{\boldsymbol{x}}\) and \(\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}\) defined in (2.3) and (2.6) satisfy

$$ \biggl|\dfrac { \partial \hat{\boldsymbol{y}}}{ \partial {\alpha } } \biggr|^{2}= \biggl|\dfrac { \partial \hat{\boldsymbol{x}}}{ \partial {\alpha } } \biggr|^{2}, \qquad \dfrac { \partial \hat{\boldsymbol{y}}}{ \partial {\alpha } } \cdot \dfrac { \partial \hat{\boldsymbol{y}}}{ \partial {\beta } } =\dfrac { \partial \hat{\boldsymbol{x}}}{ \partial {\alpha } } \cdot \dfrac { \partial \hat{\boldsymbol{x}}}{ \partial {\beta } } , \quad\text{and}\quad \biggl|\dfrac { \partial \hat{\boldsymbol{y}}}{ \partial {\beta } } \biggr|^{2}= \biggl|\dfrac { \partial \hat{\boldsymbol{x}}}{ \partial {\beta } } \biggr|^{2} $$(2.12)for each parameter pair \((\alpha,\beta)\) corresponding to a point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) or, equivalently, by (2.4)–(2.6), \(\boldsymbol{R}\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}\) satisfy

$$ \boldsymbol{R}^{\prime}\boldsymbol{b}=\boldsymbol{0}, $$(2.13)for each admissible choice of the only argument \(\alpha\) on which they depend.

For all remaining subsections of the present section, we assume that the first of the above bullet items holds and focus only on exploring the ramifications of the condition (2.13) necessary and sufficient to ensure that the second bullet item holds. Later, in Sect. 4, we consider the remaining bullet item.

2.2 Alternative Conditions for Isometry

Since \(\boldsymbol{R}^{\prime}\boldsymbol{b}=\boldsymbol{R}^{\prime }\boldsymbol{R}^{\top }\boldsymbol{R}\boldsymbol{b}=\boldsymbol {R}^{\prime}\boldsymbol{R}^{\top }\boldsymbol{a}\), it is convenient to introduce the axial vector

of the skew tensor \(\boldsymbol{R}^{\prime}\boldsymbol{R}^{\top }\) associated with the rotation \(\boldsymbol{R}\) and to express the isometry condition (2.13) in the equivalent alternative form

As an immediate consequence of (2.4), we see that \(\tilde {\boldsymbol{y}}\) defined by (2.8) is an isometric deformation if and only if \(\boldsymbol{p}\) and \(\boldsymbol{a}\) are collinear. Thus, \(\boldsymbol{p}\) must be tangent to \({\mathcal{S}}\). Moreover, since \(|\boldsymbol{a}|=|\boldsymbol{R}\boldsymbol {b}|=|\boldsymbol{b}|=1\), (2.13) holds if and only if \(\boldsymbol{p}\) satisfies \(\boldsymbol{p}=(\boldsymbol{a}\otimes \boldsymbol{a})\boldsymbol{p}\) and thus admits the representationFootnote 3

In accord with its definition (2.14) and representation (2.16), \(\boldsymbol{p}\) is the rate of rotation of the generators of \({\mathcal{S}}\) along the spatial directrix \({\mathcal{C}}\). Moreover, that rate has magnitude \(|\boldsymbol{p}|=p\).

Recalling the definition (2.14) of \(\boldsymbol{p}\), we may rewrite (2.13) as a tensorial ordinary-differential-equation

for \(\boldsymbol{R}\), where \(\boldsymbol{A}=\boldsymbol{a}\times\) is the skew tensor with axial vector the spatial generator \(\boldsymbol {a}\). To determine the isometric deformation \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{y}}\) from \({\mathcal{D}}\) to \({\mathcal{S}}\), it is therefore necessary to first solve (2.17) for the rotation tensor \(\boldsymbol{R}\) subject to an initial condition \(\boldsymbol{R}(0)=\boldsymbol{R}_{0}\), with \(\boldsymbol{R}_{0}\) being a given rotation. This is no easy task. Indeed, (2.17) cannot be solved for \(\boldsymbol{R}\) unless \(p\) and \(\boldsymbol{a}\) are given. Although it is known that a solution exists,Footnote 4 no general explicit closed-form solution is available. The alternative is to use approximation schemes such as the classical Magnus [7] expansion method. However, there may be issues related to the dimensions of \({\mathcal{D}}\) and additional conditions which do not enter into the problem statement of (2.17) that are necessary to assure that no self-intersection occurs. A general solution strategy that overcomes these obstacles does not yet exist. A complete explicit treatment of the particular example of the isometric deformation of a rectangular material strip onto a portion of a right circular conical surface is provided by Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1, Sect. 9].

2.3 Framing of the Spatial Directrix

The orthonormal triad \(\{\boldsymbol{e}_{1},\boldsymbol {e}_{2},\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\}\) with elements

provides a framing of the spatial directrix \({\mathcal{C}}\). From (2.1) and (2.18), we infer that \(\boldsymbol{e}_{1}\) is tangent to \({\mathcal{S}}\), \(\boldsymbol{e}_{2}\) is normal to \({\mathcal {S}}\), and \(\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\) is tangent to \({\mathcal{C}}\) and, thus, also to \({\mathcal{S}}\). Recalling that \(\{\boldsymbol {l}_{1},\boldsymbol{l}_{2},\boldsymbol{l}_{3}\}\) is also an orthonormal triad, we see from (2.18) that \(\boldsymbol{R}\) entering (2.18) admits the representation

Moreover, using (2.18) in the expression (2.5) for the generator \(\boldsymbol{a}\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) corresponding to the ruling \(\boldsymbol{b}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\) defined by (2.2), we find that

Recalling (2.16), we therefore arrive at a representation,

for the axial vector \(\boldsymbol{p}\) of the skew tensor \(\boldsymbol {R}^{\prime}\boldsymbol{R}^{\top }\) associated with the rotation \(\boldsymbol{R}\).

2.4 Darboux Vector of the Spatial Directrix

From the theory of framed curves (Bishop [8]), it is known that the variation of the triad \(\{\boldsymbol{e}_{1},\boldsymbol {e}_{2},\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\}\) along \({\mathcal{C}}\) is completely described, modulo a rigid transformation, by the differential equation

where \(\boldsymbol{\delta}\) is the Darboux vector of \({\mathcal{C}}\). The components \(\delta_{i}=\boldsymbol{\delta}\cdot\boldsymbol {e}_{i}\), \(i=1,2,3\), of \(\boldsymbol{\delta}\) relative to \(\{ \boldsymbol{e}_{1},\boldsymbol{e}_{2},\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\}\) can be found from (2.22) and are given by

Since \(\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\) is tangent to \({\mathcal{C}}\), its arclength derivative \(\boldsymbol{e}_{3}^{\prime}\) is the curvature vector of \({\mathcal{C}}\). While \(\delta_{1}\) and \(\delta_{2}\) measure the curvature of \({\mathcal{C}}\) about \(\boldsymbol{e}_{2}\) and \(\boldsymbol {e}_{1}\), respectively, \(\delta_{3}\) describes the precession of \(\{ \boldsymbol{e}_{1},\boldsymbol{e}_{2},\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\}\) about \(\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\).

Bearing in mind the relation (2.18) determining \(\{ \boldsymbol{e}_{1},\boldsymbol{e}_{2},\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\}\) in terms of the referential triad \(\{\boldsymbol{l}_{1},\boldsymbol {l}_{2},\boldsymbol{l}_{3}\}\) and the alternative version (2.15) of the isometry condition (2.13), we next consider how the restrictions (2.1) on \(\{\boldsymbol{l}_{1},\boldsymbol{l}_{2},\boldsymbol{l}_{3}\}\) influence the properties of the Darboux vector \(\boldsymbol{\delta}\) of \({\mathcal {C}}\). Toward this objective, we first define the scalar curvature \(k\) of the referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) in accord with

Differentiating (2.1) with respect to arclength, we then find that

Then, using the respective consequences

and

of (2.14) and (2.18) to simplify the condition that ensues upon differentiating (2.18) with respect to arclength, we arrive at a differential equation

which, when compared with (2.22), leads to the conclusion that the Darboux vector \(\boldsymbol{\delta}\) must be of the form

By (2.16), (2.20), and (2.29), the components of \(\boldsymbol{\delta}\) relative to \(\{\boldsymbol{e}_{1},\boldsymbol {e}_{2},\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\}\) can now be expressed as

Moreover, by (2.23), the curvature vector \(\hat{\boldsymbol {y}}_{0}^{\prime\prime}=\boldsymbol{e}_{3}^{\prime}\) of \({\mathcal {C}}\) takes the form

Since \(\{\boldsymbol{e}_{1},\boldsymbol{e}_{2},\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\}\) is orthonormal with \(\boldsymbol{e}_{2}\) being normal to \({\mathcal{S}}\) and \(\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\) being tangent to \({\mathcal{C}}\), we see from (2.30)1,2 and (2.31) that, as a curve in the surface \({\mathcal{S}}\), \({\mathcal{C}}\) has normal and geodesic curvatures

Lastly, from (2.30)3, we note that as \(\{\boldsymbol {e}_{1},\boldsymbol{e}_{2},\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\}\) traverses \({\mathcal {C}}\) it rotates about \(\boldsymbol{e}_{3}\) with “angular velocity” \(\delta_{3}={p\nu}/{\sqrt{1+\nu^{2}}}\).

Since \(k=k_{g}\) by (2.32)2, the representation (2.29) for the Darboux vector \(\boldsymbol{\delta}\) of \({\mathcal {C}}\) can be rewritten in the form \(\boldsymbol{p}+k_{g}\boldsymbol {e}_{2}\). We thus see that the basic isometry condition (2.13) is equivalent to the requirement that

Adapting calculations performed by Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1, Sect. 6] to the present setting, we find that the curvature tensor \(\boldsymbol{L}=-\text{grad}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\boldsymbol{e}_{2}\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) takes the explicit form

where \(\boldsymbol{a}^{\perp}\) is the unit vector field, orthogonal to \(\boldsymbol{a}\), defined by

Since \(\boldsymbol{a}\times\boldsymbol{a}^{\perp }=\boldsymbol{e}_{2}\), \(\{\boldsymbol{a},\boldsymbol {a}^{\perp},\boldsymbol{e}_{2}\}\) provides an orthonormal basis for \(\mathbb{V}^{3}\) on \({\mathcal{S}}\).

3 Interpretation of the Class of Mappings Considered by Dias and Audoly [2]

To describe a strip-like material surface in a planar reference configuration and in an associated deformed configuration obtained by bending, Dias and Audoly [2, equation (5)] introduce, in their notation, ruled parametrizations

and

where \(S\) measures arclength along the directrices parametrized by \(\boldsymbol{X}\) and \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(V\) determines position along the referential rulings and spatial generators that are respectively parallel to \(\boldsymbol{Q}\) and \(\boldsymbol{q}\).Footnote 5 The vector quantities \(\boldsymbol{Q}\) and \(\boldsymbol{q}\) are taken to be of the form

where \(\{\boldsymbol{D}_{1},\boldsymbol{D}_{2},\boldsymbol{D}_{3}\}\) and \(\{\boldsymbol{d}_{1},\boldsymbol{d}_{2},\boldsymbol{d}_{3}\}\) are moving orthonormal triads for the referential and spatial directrices, \(\boldsymbol{D}_{3}\) and \(\boldsymbol{d}_{3}\) satisfy the conditionsFootnote 6

which are familiar from the description of framed curves (and Kirchhoff rods), and \(\eta\) is the tangent of the shared angle between \(\boldsymbol{D}_{1}\) and \(\boldsymbol{Q}\) and between \(\boldsymbol {d}_{1}\) and \(\boldsymbol{q}\). Here, and in the remainder of this section, a superscripted prime is used to denote differentiation with respect to the arclength parameter \(S\). Since in differential geometry, the surfaces that are isometric to planar regions are the special ruled surfaces that are developable, and these surfaces are not necessarily isometric deformations of one another, and since the work of Dias and Audoly [2] is based on this differential geometric concept of isometry, further explanation of their work seems necessary.

Dias and Audoly [2] refer to \(S\) and \(V\) as “longitudinal” and “transverse” coordinates. From (3.4), \(S\) provides a one-to-one correspondence between points on the referential directrix, which Dias and Audoly [2] identify as a locus of material points,Footnote 7 and their images on the spatial directrix. An analogous statement does not, however, apply to \(V\). This raises a need to properly characterize the inescapably material points that lie on the edges of the material surface. To address this need, Dias and Audoly [2] introduce “edge functions” \(V_{\pm}(\eta,S)\) and in this regard state that “\(S\) varies in the interval \(0\le S\le L\), where \(L\) is the curvilinear length of the center-line,” and that “\(V\) varies in a domain \(V_{-}(\eta,S)\le V\le V_{+}(\eta,S)\)”, where “\(V_{\pm}(\eta,S)\) encode the relative positions of the edges of the material surface with respect to the center-line”.Footnote 8 However, they do not explain whether—or, if so, how—the ordered pairs \((S,V)\) correspond to material points.

Because Dias and Audoly [2] require that the directrices are loci of material points, their framework does not apply in situations where the directrices include segments that lie outside the boundaries of the referential and spatial manifestations of the material surface. For this reason, only under special circumstances would the corresponding collection

of all admissible combinations of \(S\) and \(V\) cover the material surface in either of its configurations. The ramifications of this lapse are addressed in Sect. 4.

From (3.3), we see that \(\{\boldsymbol{D}_{1},\boldsymbol {D}_{2},\boldsymbol{D}_{3}\}\) and \(\{\boldsymbol{d}_{1},\boldsymbol {d}_{2},\boldsymbol{d}_{3}\}\) are selected so that \(\boldsymbol{D}_{2}\) is normal to the plane occupied by the material surface in the reference configuration and that \(\boldsymbol{d}_{2}\) is normal to the tangent space of the spatial surface occupied by the material surface in the deformed configuration. This assumption leads to supplemental conditions of the formFootnote 9

While (3.6)1 expresses the requirement that the geodesic curvature of the spatial directrix must equal the curvature of the (flat) referential directrix, (3.6)2 expresses the additional requirement that, in the spatial configuration, the material surface can manifest only developable shapes.

Dias and Audoly [2] do not explicitly state how a ruling parallel to \(\boldsymbol{Q}\) must be rotated to obtain the corresponding generator \(\boldsymbol{q}\). However, an implicit feature of their description is that the spatial triad \(\{\boldsymbol{d}_{1},\boldsymbol {d}_{2},\boldsymbol{d}_{3}\}\) is obtained by transforming the referential triad \(\{\boldsymbol{D}_{1},\boldsymbol{D}_{2},\boldsymbol {D}_{3}\}\) by a counterpart rotation

of the rotation \(\boldsymbol{R}\) defined in (2.19). A particular consequence of this is that, analogous to the relation (2.5) between the referential rulings and spatial generators,

In view of (3.8), there is an unmistakable correspondence between (3.1)–(3.2) and (2.3)–(2.6). Indeed, (3.1)–(3.2) can be transformed into (2.3)–(2.6) by making the simple change of variablesFootnote 10

and introducing the identifications

from which it follows that

where \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\) is the Darboux vector entering (6)–(7*) of Dias and Audoly [2]. On this basis, we see that the developability constraints (3.6)1 and (3.6)2 that they impose are implied by (2.32)2 and (2.30)1,3, respectively. Moreover, from the identity

which arises from (7*), (10*), and (11*) of Dias and Audoly [2], we deduce that

Thus, with reference to (3.9)–(3.11), we infer that the condition (2.33) necessary and sufficient to ensure isometry of the deformation is satisfied. Granted that the conditions (3.4) and (3.6) apply, the mapping \(\boldsymbol {Y}\mapsto\boldsymbol{y}\) determined implicitly by (3.1) and (3.2) therefore satisfies the second of the bullet items entering the characterization of an isometric deformation provided in the final paragraph of Sect. 2.1.

A more direct alternative to the foregoing argument hinges on showing that \(\boldsymbol{\varTheta}^{\prime}\boldsymbol{Q}=\boldsymbol{0}\) or, equivalently, on demonstrating that the axial vector of the skew tensor \(\boldsymbol{\varTheta}^{\prime}\boldsymbol{\varTheta}^{\top }\) is collinear with \(\boldsymbol{q}\). Specifically, calculating \(\boldsymbol{\varTheta}^{\prime}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\varTheta}^{\top }\) from (3.7), using the orthonormality of the triads \(\{ \boldsymbol{D}_{1},\boldsymbol{D}_{2},\boldsymbol{D}_{3}\}\) and \(\{ \boldsymbol{d}_{1},\boldsymbol{d}_{2},\boldsymbol{d}_{3}\}\), the analog

of (2.22), and the constraints (3.6), we see that

from which we deduce that \(\text{ax}(\boldsymbol{\varTheta}^{\prime }\boldsymbol{\varTheta}^{\top })=\omega_{1}\boldsymbol{q}\), confirming thereby that, granted (3.4) and (3.6), the mapping \(\boldsymbol{Y}\mapsto\boldsymbol{y}\) determined by (3.1) and (3.2) constitutes an isometric deformation as defined by Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1] and recapitulated in Sect. 2.1 of the present paper.Footnote 11

4 Importance of the Correspondence Between Curvilinear Coordinate Pairs and Material Points

We next focus on the requirement that each coordinate pair \((\alpha ,\beta)\) corresponds to a unique material point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) and, moreover, that the underlying correspondence between coordinate pairs and points provides a complete covering of \({\mathcal{D}}\).Footnote 12 Together, these requirements ensure that the relationship between coordinate pairs and material points is surjective.

4.1 General Considerations

Although Dias and Audoly [2] do not mention this requirement, an appreciation of its importance is evident from their introduction of “edge functions” \(V_{\pm}(\eta,S)\). For the particular case in which the reference configuration of the material surface is a rectangular strip, Dias and Audoly [2] choose \(V_{\pm}(\eta,S)\) so that the collection of parameter pairs \((S,V)\) covers the region occupied by the material surface in its reference configuration, but that choice restricts the referential rulings to be perpendicular to the referential directrix, which they take to be midway between the long edges of the strip, and consequently limits the parametrizations (3.1) and (3.2) to describe only the bending of a rectangular material strip into a right circular cylindrical form. It does not, for instance, encompass the bending of a rectangular material strip into a helical ribbon coincident with a portion of a right cylindrical surface or into a conical ribbon coincident with a portion of a right circular conical surface, wherein the referential rulings must be inclined relative to the referential directrix (as discussed later in this section).

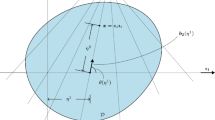

Returning to the general difficulty raised in the second paragraph of Sect. 3, because Dias and Audoly [2] stipulate that their longitudinal coordinate \(S\) satisfies \(0\le S\le L\), the measures that they introduce in connection with their edge functions \(V_{\pm}(\eta,S)\) rarely suffice to ensure that the collection (3.5) of \((S,V)\) pairs completely covers the planar region occupied by the material surface in the reference configuration and, thus, the curved surface it occupies in the spatial configuration. This difficulty is evident even in the first figure of their paper, a partial counterpart of which appears in our Fig. 1. For the particular directrices, rulings, and generators depicted in that image, two corners of the material surface in the reference configuration go uncovered by rulings and the same is true of the associated corners of the deformed material surface. No element \((S,V)\) of (3.5) can describe a material point in either of those corners. With reference to Fig. 1, this consequence of stipulating that the referential and spatial directrices are loci of material points,Footnote 13 can be rectified by extending the range of the transverse coordinate \(S\) beyond \(0\le S\le L\), resulting in directrices that include nonmaterial segments outside the boundaries of the material surface. Again making reference to Fig. 1, this must be accompanied by the introduction of corresponding rulings and generators that reach from the nonmaterial portions of the directrices into the previously uncovered portions of the material surface. It then remains to correctly delineate the range of \(V\) for the rulings and generators corresponding to each point, whether material or nonmaterial, on the directrices.

Schematic of (a) a planar material surface and (b) an isometric deformation of that material surface. (Inspired by Dias and Audoly [2, Fig. 1].) In the reference configuration, two corners of the material surface go unruled unless the referential directrix includes segments that are disjoint from the referential region occupied by the material surface. The corresponding corners of the surface identified with the material surface in its deformed configuration do not possess generators unless the spatial directrix includes corresponding segments that are disjoint from that surface. The segments of the directrices that lie on the material surface and, thus, consist of material points, are indicated in white, as are the rulings and generators needed to fully cover the material surface in the reference and deformed configurations. The segments of the directrices that are disjoint from the material surface and, thus, do not contain material points, are indicated in red. The rulings and generators that intersect those segments are red outside of the referential and spatial manifestations of the material surface and white inside those manifestations

4.2 Example: Isometric Deformation of a Rectangular Material Strip to a Helical Sector of a Cylindrical Surface

We consider the isometric deformation of a rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) onto a helical sector \({\mathcal{S}}\) of a right circular cylindrical surface \(\mathcal{Y}\) of radius \(r_{0}\). To simplify the discussion, we identify the spatial manifestation of \({\mathcal{D}}\) with \({\mathcal{S}}\) and refer to \({\mathcal{S}}\) as a ‘helical ribbon’.

Employing the definitions and notation introduced at the outset of Sect. 2, we identify the reference configuration of the strip with the planar region

where \(x_{1}\) and \(x_{2}\) serve as rectilinear coordinates for \(\mathbb {E}^{2}\) in the directions of \(\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\imath}_{2}\). Each ordered pair of \((x_{1},x_{2})\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) then corresponds to a unique material point \(\boldsymbol {x}=\boldsymbol{o}+x_{1}\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1}+x_{2}\boldsymbol {\imath}_{2}\), where \(\boldsymbol{o}\) denotes the point at the origin. Moreover, we rule \({\mathcal{D}}\) with a family of parallel straight lines inclined at an angle \(\theta_{0}\), satisfying

if measured counterclockwise from the \(\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1}\) direction, and take the referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) to be a closed subinterval of the line \(x_{2}=0\), as illustrated in Fig. 2. Aside from rulings that pass through the material points on the midline \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\cap{\mathcal{D}}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\), there exist rulings that are connected to nonmaterial points on the segments of \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) that lie on either side of \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\cap{\mathcal{D}}\). Without these nonmaterial segments of \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\), it is impossible to ensure that each coordinate pair \((\alpha,\beta)\) corresponds to a unique material point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) and, moreover, that the underlying correspondence between coordinate pairs and points covers \({\mathcal{D}}\) completely.

A rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) of length \(\ell\) and width \(w\) identified with the planar region \(\{(x_{1},x_{2}):0\le x_{1}\le\ell,-w/2\le x_{2}\le w/2\}\) and ruled by a family of parallel lines oriented at angle \(\theta_{0}\) satisfying \(0<\theta _{0}<\pi/2\) when measured clockwise from the line \(x_{2}=0\). The strip is completely covered by the collection \({\mathcal{P}}\) of \((\alpha ,\beta)\) coordinate pairs defined in (4.7). The curvilinear coordinates \((\alpha,\beta)\) of a material point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) with rectilinear coordinates \((x_{1},x_{2})\) are given by (4.4)

Following Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1, Sect. 7.1], an isometric deformation \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{y}}\) from \({\mathcal{D}}\) to \({\mathcal{S}}\) can be expressed as

where \(\tilde{\alpha}\) and \(\tilde{\beta}\) are given, for each \(\boldsymbol{x}=x_{i}\boldsymbol{\imath}_{i}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) and each \(\theta_{0}\) satisfying (4.2) by

and the parametrization \(\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}_{0}\) of the spatial directrix \({\mathcal{C}}\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) is defined according to

The spatial directrix \({\mathcal{C}}\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) is a helix of lead angle \(\pi/2-\theta_{0}\) and the generators of \({\mathcal{S}}\) are parallel to the axis of \(\mathcal{Y}\). Moreover, \({\mathcal{S}}\) is right-handed according to the direction of \(\boldsymbol{\imath}_{3}\). An image showing the shapes determined by using \(\tilde{\boldsymbol {y}}\) defined through (4.3)–(4.5), for \(\theta _{0}=\pi/6\) and \(\theta_{0}=\pi/3\), to isometrically deform a rectangular strip of length \(\ell=5r_{0}\) and width \(w=r_{0}/2\) onto a right circular cylindrical surface \(\mathcal{Y}\) of radius \(r_{0}\) appear in Fig. 3.

Helical ribbons determined by using \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{y}}\) defined through (4.3)–(4.5), with \(\theta _{0}=\pi/6\) and \(\theta_{0}=\pi/3\), to isometrically deform a rectangular strip of length \(\ell=5r_{0}\) and width \(w=r_{0}/2\) onto a right circular cylinder \(\mathcal{Y}\) with axis parallel to \(\boldsymbol {\imath}_{3}\) and radius \(r_{0}\)

With reference to Fig. 2 and bearing in mind that, by (4.4)1, \(x_{1}=\alpha\) if \(x_{2}=0\), a trigonometric exercise shows that the referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) is given by

Consistent with the statements immediately after (4.2), the referential and spatial directrices must therefore include segments that extend beyond the edges of \({\mathcal{D}}\). Moreover, the collection of \((\alpha,\beta)\) coordinate pairs needed to describe each material point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) belonging to \({\mathcal{D}}\) can be expressed as

In the current notation and with an essential correction of their edge functions,Footnote 14 the specialization of (3.5) that Dias and Audoly [2] would consider has the form (Fig. 4)

In view of (4.4), the subset of the \((x_{1},x_{2})\)-plane covered by \(\bar{{\mathcal{P}}}\) is not \({\mathcal {D}}\) but rather

Hence, \(\bar{{\mathcal{P}}}\) fails to cover the triangular subregions

and

of \({\mathcal{D}}\). Additionally, \(\bar{{\mathcal{P}}}\) contains ordered pairs \((\alpha,\beta)\) that correspond to nonmaterial points in the triangular regions

and

both of which are disjoint from \({\mathcal{D}}\) but have areas equal to those of the missing regions (4.10) and (4.11) respectively, (Fig. 4). The collection of coordinate pairs in \(\bar{{\mathcal{P}}}\) is therefore not only insufficient to describe all material points in \({\mathcal{D}}\) but also includes spurious elements that are not needed to describe material points in \({\mathcal{D}}\).

The set \(\bar{{\mathcal{D}}}\) of \((x_{1},x_{2})\) pairs determined by all combinations of \((\alpha,\beta)\) pairs in the set \(\bar{{\mathcal{P}}}\) defined in (4.8). Material points in the triangular subregions of (4.10) and (4.11) of \({\mathcal{D}}\) are missing from \(\bar {{\mathcal{D}}}\); moreover, \(\bar{{\mathcal{D}}}\) contains spurious nonmaterial points belonging to triangular regions (4.12) and (4.13) disjoint from \({\mathcal{D}}\)

In the bending of a rectangular material strip into a helical ribbon, we therefore conclude that the parametric description of Dias and Audoly [2] fails to completely cover both the planar subset \({\mathcal{D}}\) of \(\mathbb{E}^{2}\) occupied by the strip in its reference configuration and the curved surface \({\mathcal{S}}\) in \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\) identified with the helical ribbon. Moreover, that description includes extraneous coordinate pairs that do not correspond to material points of \({\mathcal{D}}\). Although we have exposed these drawbacks in the context of a special example, we emphasize that, as discussed in the previous section, their generic nature is evident from Fig. 1 of Dias and Audoly [2].

4.3 Example: Isometric Deformation of a Rectangular Strip to a Sector of a Conical Surface

Now, let us consider the isometric deformation of a rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) of length \(\ell\) and width \(w\) to a ribbon coincident with a sector \({\mathcal{S}}\) of a right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\).Footnote 15 For convenience, we continue to employ the definitions and notation introduced at the outset of Sect. 2 and, as in our treatment of the isometric deformation of a rectangular material strip to a helical ribbon, we identify the reference configuration of \({\mathcal{D}}\) with the planar region

Additionally, we rule \({\mathcal{D}}\) with a family of straight lines that intersect at a point outside of \({\mathcal{D}}\) and take the referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) to be a closed subinterval of the line \(x_{2}=0\), as illustrated in Fig. 5. As with the bending of a rectangular material strip into a helical ribbon presented in Sect. 4.2, there exist not only rulings that pass through material points on the portion \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\cap{\mathcal{D}}\) of the referential midline \(\mathcal{C}_{0}\) that lies within \({\mathcal{D}}\) but also rulings that are connected to nonmaterial points belonging to segments of \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) that lie on either side of \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\cap{\mathcal{D}}\). Moreover, these nonmaterial segments of \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) are essential to ensure that each coordinate pair \((\alpha,\beta)\) corresponds to a unique material point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\) and that the underlying correspondence between coordinate pairs and points covers \({\mathcal{D}}\) completely. Emulating our treatment of the example considered in Sect. 4.2, we identify the spatial manifestation of the material surface with the subset \({\mathcal{S}}\) of \({\mathcal{K}}\) and refer to \({\mathcal{S}}\) as a ‘conical ribbon’ (see Fig. 6).

The rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) of length \(\ell \) and width \(w\) showing some members of the family of intersecting straight lines which become the lines of zero principal curvature of the subset \({\mathcal{S}}\) of a right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\). The corresponding referential rulings of \({\mathcal{D}}\) are the white segments of those lines. The referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) is indicated in red. The length of a generator of the portion of the right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\) that lies above the plane spanned by \(\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\imath}_{2}\) is denoted by \(\varLambda\). The curvilinear coordinates \((\alpha,\beta)=(\tilde{\alpha}(\boldsymbol{x}),\tilde {\beta}(\boldsymbol{x}))\) of the material point \(\boldsymbol{x}\in {\mathcal{D}}\) with rectilinear coordinates \((x_{1},x_{2})\) are given by (4.20)

The right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\) and the rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) shown attached at \(R\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1}\) and tangent to \({\mathcal{K}}\) along the generator defined by \(\boldsymbol{a}\). Each point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\) is translated by the constant vector \(R\boldsymbol {\imath}_{1}\) and the vector between the origin and that point is then rotated about the point \(R\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1}\) by the linear transformation \(\boldsymbol{Q}_{0}\) defined in (9.14) of Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1], the effect of which is to map the ruling of \({\mathcal{D}}\) parallel to \(\boldsymbol{b}(0)\) to the generator of \({\mathcal{S}}\) parallel to \(\boldsymbol{a}=\boldsymbol {Q}_{0}\boldsymbol{b}(0)\)

4.3.1 Characterization of the Conical Surface

We assume that \({\mathcal{K}}\) opens downward from \(H\boldsymbol{\imath}_{3}\) and intersects the \((x_{1},x_{2})\)-plane to form a circle of radius \(R\), in which case it has tip angle \(2\varphi\), with

and the generators of the portion of \({\mathcal{K}}\) that is situated above the \((x_{1},x_{2})\)-plane are of length

With reference to Fig. 5, we denote the angle between \(\boldsymbol{\imath}_{1}\) and the referential ruling, with orientation \(\boldsymbol{b}(0)\), that passes through the left-hand end point \((x_{1},x_{2})=(0,0)\) of the midline of \({\mathcal{D}}\) by \(\theta _{0}\) and without loss of generality require that

To ensure that for all lengths \(\ell> \varLambda\cos\theta_{0}\), \({\mathcal{S}}\) is wrapped smoothly onto \({\mathcal{K}}\) without intersecting with the tip of \({\mathcal{K}}\), we restrict the width \(w\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\) to satisfy the inequality \(w<2\varLambda\sin\theta _{0}\). To be definite in all subsequent calculations, we shall assume that \(\ell>\varLambda\cos\theta_{0}\) so that both of the following inequalities hold:

4.3.2 Characterization of the Deformation

Following Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1, Sect. 9.1], the isometric deformation \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{y}}\) that bends the rectangular strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) onto the right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\) in such a way that the left-hand endpoint of its midline lies on the circle of radius \(R\) along which \({\mathcal {K}}\) intersects the \((x_{1},x_{2})\)-plane, as depicted in Fig. 6 can be expressed as

where \(\tilde{\alpha}\) and \(\tilde{\beta}\) are given, for each \((x_{1},x_{2})\) in \((0,\ell)\times(-w/2,w/2)\) and each \(\theta_{0}\) satisfying (4.17), by

and the spatial directrix \({\mathcal{C}}\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) is parametrized by \(\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}_{0}\) defined according to

in which \(\theta(\alpha)\) satisfying

is the angle formed by the referential ruling with orientation \(\boldsymbol{b}(\alpha)\) and the orientation \(\boldsymbol{\imath }_{1}\) of the referential directrix and \(\omega\) is related linearly to \(\theta\) through

4.3.3 Coverage of the Strip by Curvilinear Coordinates

Referring to Fig. 5 and noticing that, by (4.20)1, \(x_{1}=\alpha\) if \(x_{2}=0\), we find on the basis of trigonometric exercises that the referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) is given by

where \(\alpha_{-}\) and \(\alpha_{+}\) are defined according to

and, consistent with the restrictions (4.18) on \(\ell\) and \(w\) and the observation that \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) must extend beyond \({\mathcal{D}}\), obey

We next determine the collection of \((\alpha,\beta)\) coordinate pairs that belong to each edge of \({\mathcal{D}}\). For clarity, we label those edges as follows:

Focusing first on \({\mathcal{L}}_{0}\) and \({\mathcal{L}}_{\ell}\), we see from (4.20) that the values of the \(\alpha\) coordinate at the material points \((x_{1},x_{2})=(0,-w/2)\) and \((x_{1},x_{2})=(\ell ,-w/2)\) at the lower left and lower right corners of \({\mathcal{D}}\) are

respectively. Applying the restrictions (4.18) on \(\ell \) and \(w\) to (4.28), we see further that \(\alpha_{0}\) and \(\alpha_{\ell}\) must be such that

Since the values of the \(\alpha\) coordinate at the material points \((x_{1},x_{2})=(0,w/2)\) and \((x_{1},x_{2})=(\ell,w/2)\) at the upper left and right corners of \({\mathcal{D}}\) are \(\alpha_{-}\) and \(\alpha _{+}\), respectively, we thus conclude from (4.20) that \({\mathcal {L}}_{0}\) and \({\mathcal{L}}_{\ell}\) can be described as

and

where \(\beta_{0}\) and \(\beta_{\ell}\) are defined according to

with \(\rho\) given by

From (4.20), we next see that \({\mathcal{L}}_{\pm}\) can be described as

where \(\beta_{\pm}\) are defined by

Each referential ruling connects two edges of \({\mathcal{D}}\) and lies on a straight line defined by a point \((\alpha,0)\), with \(\alpha _{-}\le\alpha<\alpha_{+}\), on the referential directrix and the nonmaterial point \((x_{1},x_{2})=(\varLambda\cos\theta_{0},\varLambda\sin \theta_{0})\) corresponding to the apex of the right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\). The point \((\alpha,0)\) is material if \(0\le \alpha\le\ell\) and nonmaterial if \(\alpha_{-}\le\alpha<0\) or \(\ell<\alpha\le\alpha_{+}\). The referential rulings

and

connect the lower left and right corners \((x_{1},x_{2})=(0,-w/2)\) and \((x_{1},x_{2})=(\ell,-w/2)\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\) to the upper edge \({\mathcal{L}}_{+}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\) and naturally decomposes \({\mathcal{D}}\) into a union of three subregions, each distinguished by the features of its rulings, as depicted in Fig. 7. This decomposition consists of:Footnote 16

-

A trapezoid within which all rulings extend from the lower edge \({\mathcal{L}}_{-}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\) and the upper edge \({\mathcal{L}}_{+}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\). This subregion of \({\mathcal {D}}\) consists of all coordinate pairs \((\alpha,\beta)\) belonging to

$$ {\mathcal{T}}_{c}=\bigl\{ (\alpha,\beta):\alpha_{0}\le \alpha\le\alpha _{\ell},\beta_{-}(\alpha)\le\beta\le \beta_{+}(\alpha)\bigr\} . $$(4.38) -

A triangle within which all rulings extend from the left edge \({\mathcal{L}}_{0}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\) and the upper edge \({\mathcal{L}}_{+}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\). This subregion of \({\mathcal {D}}\) consists of all coordinate pairs \((\alpha,\beta)\) belonging to

$$ {\mathcal{T}}_{0}=\bigl\{ (\alpha,\beta):\alpha_{-}\le \alpha\le\alpha _{0},\beta_{0}(\alpha)\le\beta\le \beta_{+}(\alpha)\bigr\} . $$(4.39) -

A triangle within which all rulings extend from the right edge \({\mathcal{L}}_{\ell}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\) and the upper edge \({\mathcal{L}}_{+}\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\). This subregion of \({\mathcal{D}}\) consists of all coordinate pairs \((\alpha,\beta)\) belonging to

$$ {\mathcal{T}}_{\ell}=\bigl\{ (\alpha,\beta):\alpha_{\ell}\le \alpha\le \alpha_{+},\beta_{\ell}(\alpha)\le\beta\le \beta_{+}(\alpha)\bigr\} . $$(4.40)

Decomposition of the rectangular material strip \({\mathcal {D}}\) of length \(\ell\) and width \(w\) into a trapezoidal subregion and two triangular subregions. The strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) is completely covered by the collection of \((\alpha,\beta)\) coordinate pairs in the union \({\mathcal{T}}_{0}\cup{\mathcal{T}}_{c}\cup{\mathcal{T}}_{\ell }\) of the sets defined in (4.38)–(4.40). The values \(\alpha_{0}\) and \(\alpha_{\ell}\) of \(\alpha\) that determine the inclinations of the rulings that emanate from the lower left and lower right corners of \({\mathcal{D}}\) appear in (4.28)

4.3.4 Incomplete Coverage of the Strip by Curvilinear Coordinates

In the current notation and with a necessary correction of their edge functions, the specialization of (3.5) that Dias and Audoly [2] would consider has the form

We immediately see that all pairs \((\alpha,\beta)\) in the subsets

and

of \({\mathcal{T}}_{0}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}_{\ell}\) are absent from \({\mathcal{A}}\); hence, \({\mathcal{A}}\) fails to cover the triangular subregions

and

of \({\mathcal{D}}\), as illustrated in Fig. 8. Additionally, since for each choice of \(\alpha_{*}\) satisfying \(0\le \alpha_{*}<\alpha_{-}\) or \(\alpha_{+}<\alpha_{*}\le\ell\), the ruling

extends beyond the boundary of \({\mathcal{D}}\), \({\mathcal{A}}\) contains ordered pairs \((\alpha,\beta)\) that correspond to spurious nonmaterial points in the triangular regions

and

both of which are disjoint from \({\mathcal{D}}\), as illustrated in Fig. 8. Importantly, the areas of the spurious regions (4.47) and (4.48) are the same as those of the missing subregions (4.44) and (4.45), respectively.

Covering of the \((x_{1},x_{2})\)-plane provided by the set \({\mathcal{A}}\) of \((\alpha,\beta)\) pairs defined in (4.41). In addition to missing all material points belonging to the triangular subregions (4.44) and (4.45) of \({\mathcal{D}}\), \({\mathcal{A}}\) contains pairs \((\alpha,\beta)\) that correspond to spurious nonmaterial points in the triangular regions (4.47) and (4.48) disjoint from \({\mathcal{D}}\)

5 Bending Energies

In a tradition that traces back at least to Sadowsky’s [5, 6] formulation of a variational problem for determining the equilibrated shape of a Möbius band in the absence of external loading, it is common to take the bending energy \(E\) stored in bending an unstretchable material surface with planar rectangular reference shape \({\mathcal{D}}\) in \(\mathbb{E}^{2}\) into a curved surface \({\mathcal {S}}\) in \(\mathbb{E}^{3}\) to be given by

where \(\mu>0\) is the bending modulus of the material surface and \(H\) and \(\text{d}a\) denote the mean curvature and area element of \({\mathcal {S}}\). In (5.1), \(E\) is evaluated in the deformed configuration of the material surface. Alternatively, it is possible to parametrize \(E\) using the rectilinear or curvilinear coordinates of the material points of \({\mathcal{D}}\). For the second of these options, it is however essential to ensure that the limits of integration are determined consistent with the need to ensure that the curvilinear coordinates completely cover \({\mathcal{D}}\)!

To illustrate the importance of the foregoing statement, we next consider three particular examples involving isometric deformations of rectangular material strips.

5.1 Example 1: Bending Energy of a Rectangular Strip Isometrically Deformed to a Ribbon Coincident with a Sector of a Conical Surface

In this first example, we consider the calculation of the stored energy for a rectangular strip that is isometrically deformed into a portion of a right circular conical surface and compare this calculation to those predicted by the related Sadowsky and Wunderlicht functionals.

5.1.1 Rectilinear Parametrization of the Bending Energy

Since the deformation \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{y}}\) defined by (4.19) is isometric, the mean curvature \(H\) of the conical ribbon \({\mathcal{S}}\) is equal to one half the nonvanishing principal curvature of \({\mathcal {S}}\). Moreover, the area element \(\text{d}a(\boldsymbol{y})\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) obeys \(\text{d}a(\boldsymbol{y})=\text{d}a(\boldsymbol {x})=\text{d}x_{1}\text{d}x_{2}\). Using (9.59) of Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1], which gives the nonvanishing principal curvature of \({\mathcal{S}}\) as a function of the rectilinear coordinates \((x_{1},x_{2})\) of the material points in \({\mathcal{D}}\), we thus find that the bending energy \(E\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) obtained by specializing (5.1) to the deformation \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{y}}\) defined by (4.19)–(4.23) can be expressed as

Evaluating the innermost integral in (5.2), which is elementary for each \(x_{2}\) in \((-w/2,w/2)\), introducing the change of variables

and defining

we see that

The integral (5.5) is not elementary but can be expressed in terms of the inverse tangent integral \(\text{Ti}_{2}\), as defined by (Lewin [10, Chap. II])

Specifically, using (5.6) and recalling the definitions (5.4) of \(u_{\pm}\) and \(a\), we arrive at the representation

Using the definitions (4.25) of \(\alpha_{\pm}\) and (4.28) of \(\alpha_{0}\) and \(\alpha_{\ell}\) in (5.4), we see that (5.2) takes the alternative form

Modulo the scale factor \(\mu \cot ^{2}\varphi /2\) determined by the bending modulus \(\mu\) of the material surface and the opening angle \(2\varphi \) of the right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\), the bending energy \(E\) stored in isometrically deforming a rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) of length \(\ell\) and width \(w\) into a ribbon \({\mathcal{S}}\) on \({\mathcal{K}}\) is therefore completely determined by the angles of the lines formed by the four corners of \({\mathcal {D}}\) and the point \((x_{1},x_{2})=(\varLambda\cos\theta_{0},\varLambda \sin\theta_{0})\) corresponding to the apex of the right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\). The alternative representation (5.8) for \(E\) can also be derived directly from (5.7) on the basis of (4.25), (4.28), the periodicity of the cotangent, and the observation that \(\text{Ti}_{2}\) is an odd function of its argument.

5.1.2 Curvilinear Parametrization of the Bending Energy

Using (9.58) of Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1], which gives the nonvanishing principal curvature of \({\mathcal{S}}\), we obtain the mean curvature of \({\mathcal{S}}\) as a function \(\hat{H}\) of the curvilinear coordinates \((\alpha,\beta)\) of the form

where \(\rho\) is defined as in (4.33). Additionally, referring to (9.59) of Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1], the Jacobian \(\hat{\jmath }\) of the transformation underlying the correspondence between material points in \({\mathcal{D}}\) and curvilinear coorindates \((\alpha,\beta )\) is given by

Taking advantage of the decomposition of \({\mathcal{D}}\) into a trapezoidal subregion and two triangular subregions described in Sect. 4.3.3 and invoking the definitions (4.38), (4.39), and (4.40) of the corresponding collections \({\mathcal{T}}_{c}\), \({\mathcal{T}}_{0}\), and \({\mathcal{T}}_{\ell}\) of coordinate pairs \((\alpha,\beta)\), we see that the bending energy \(E\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) can also be expressed as

where \(\alpha_{\pm}\), \(\alpha_{0}\), \(\alpha_{\ell}\), \(\beta_{0}\), \(\beta_{\ell}\), and \(\beta_{\pm}\) are defined by (4.25), (4.28)1, (4.28)2, (4.32)1, (4.32)2, and (4.35), respectively. Each of the innermost integrals in (5.11) can be evaluated in closed form and identities connecting the integrals over \(\alpha\) that remain can be expressed in terms of the dilogarithm \(\text{Li}_{2}\) (Lewin [10, Chap. I]). A well-established identity (Lewin [10, equation (2.3)]) connecting \(\text{Li}_{2}\) to the inverse tangent integral \(\text{Ti}_{2}\) can then be used to recover (5.7) or, equivalently, (5.8) from (5.11).

5.1.3 Wunderlich’s Functional

Wunderlich’s [3, 4] functional is a dimensionally reduced version of the bending energy \(E\) defined in (5.1), with its domain of integration being the midline of the spatial manifestation \({\mathcal{S}}\) of the material surface. We next specialize that functional to the problem of isometrically deforming the rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) to the conical ribbon \({\mathcal{S}}\) and compare the resulting expression with the bending energy \(E\) of \({\mathcal{S}}\) in either the form (5.7) determined by the rectilinear parametrization or its equivalent alternative form (5.11) determined by the curvilinear parametrization.

With reference to the material in the first two paragraphs on page 279 of Wunderlich’s [3] original paper, we gather identifications of the form

where \(\kappa\) and \(\tau\) denote the curvature and torsion of \({\mathcal{C}}\). In particular, from (4.21), we see that \(\kappa^{2}\) takes the form

with \(\rho\) as defined in (4.33). Moreover, from (9.52)2 of Chen, Fosdick and Fried [1], the relation (4.22) defining the angle \(\theta\) between the referential rulings and the referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\), and (4.33), we see that

Multiplying (6) of Wunderlich [3, 4] by a factor of \(\mu/2\) to ensure a meaningful comparison to \(E\) and invoking (5.12)–(5.29), we thus find that, for the conical ribbon \({\mathcal{S}}\), Wunderlich’s [3, 4] functional specializes toFootnote 17

Recalling the definition (4.33) of \(\rho\), we notice that the remaining integral in (5.15) is elementary and, since \(\arctan (\cot\theta_{0})=\pi/2-\theta_{0}\) for \(0<\theta<\pi\), we arrive at the closed-form representation

Since (5.16) is predicated upon integrating over the collection of \((\alpha,\beta)\) coordinate pairs that belong to \({\mathcal{A}}\) instead of the union \({\mathcal{T}}_{-}\cup{\mathcal {T}}_{c}\cup{\mathcal{T}}_{+}\) that ensures complete coverage of \({\mathcal{D}}\), we anticipate that \(E_{\text{W}}\) will underestimate the correct bending energy, as we will see in Sect. 5.1.5.

5.1.4 Sadowsky’s Functional

Prior to Wunderlich [3, 4], Sadowsky’s [5, 6] derived a dimensional reduced version of the general bending energy \(E\) defined in (5.1) under the assumption, \(w\ll\ell\), that the width of the rectangular material strip is negligible in comparison to its length. Using (5.12)4 and (5.13), the Sadowsky [5, 6] functional takes the form

where, to facilitate comparisons with \(E\) and \(E_{ \text{W}}\), we have again introduced a factor of \(\mu/2\). Following steps analogous to those leading from (5.15) to (5.16), we find that, for the problem of isometrically deforming the rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) to the conical ribbon \({\mathcal{S}}\), Sadowsky’s [5, 6] functional takes the form

Granted that \(\varLambda\) is of the same order as \(\ell\), (5.18) can also be obtained as the leading-order term in the Taylor expansion, about \(w/2\ell=0\), of either the rectilinear parametrization (5.2) of \(E\) or the closed-form expression (5.16) for \(E_{\text{W}}\).

Like Wunderlich’s [3, 4] functional (5.15), Sadowsky’s [5, 6] functional (5.17) involves integrating only over the material portion of the spatial directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\), namely the midline of \({\mathcal{S}}\). However, granted that \(w\ll\ell\), the portions of the directrices that extend beyond the strip and its image are of negliglible length. In this sense, the range of integration in (5.17) is consistent with the hypothesis \(w\ll\ell\). An analogous statement does not apply to Wunderlich’s [3, 4] functional, which is meant to provide an accurate approximation for the bending energy in situations where \(w\) need not be infinitesimal small in comparison to \(\ell\). We anticipate that, for \(w\ll\ell\), the error incurred by using Sadowsky’s [5, 6] functional should be comparable to that incurred by using Wunderlich’s [3, 4] functional. Granted that these observations are accurate, Wunderlich’s [3, 4] functional would appear to be of negligible utility. For \(w\ll\ell\), Sadowsky’s [5, 6] functional should suffice and otherwise—the error associated with failing to completely cover \({\mathcal{D}}\)—neither of the functionals in question is generally fit to provide a good approximation to the bending energy.Footnote 18

5.1.5 Bounds on the Wunderlich and Sadowsky Functionals

We now demonstrate that \(E_{\text{W}}\) and \(E_{\text{S}}\) given by (5.16) and (5.18) obey the bounds

with \(E\) being the bending energy defined in (5.2) or, equivalently, (5.11). The upper bounds on \(E_{ \text{S}}\) and \(E_{\text{W}}\) in (5.19) are consistent with intuitive expectations. It seems plausible that a finite contribution to \(E_{\text{W}}\) is lost passing from \(E_{\text{W}}\) to \(E_{\text{S}}\) under the assumption that \(w\ll\ell \), in which case the bound \(E_{\text{S}}< E_{\text{W}}\) should follow. The rationale in support of the bound \(E_{\text{W}}< E\) hinges on the observation that \(E_{\text{W}}\) involves integration not over the entire referential directrix \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) but, rather, integration only over the portion of \({\mathcal{C}}_{0}\) that coincides with the midline of \({\mathcal{D}}\). More precisely, \(E_{\text{W}}\) results from integrating over a collection \({\mathcal{A}}\) of \((\alpha,\beta)\) coordinate pairs that fails to completely cover \({\mathcal{D}}\) while the triangular corners of \({\mathcal{D}}\) that \({\mathcal{A}}\) fails to cover are above the referential directrix and the spurious triangular regions outside of \({\mathcal{D}}\) that \({\mathcal{A}}\) covers instead are below the referential directrix (Fig. 9). Since the areas of the missing and spurious triangular regions are identical and the curvature of the conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\) on any generator increases monotonically as \(\beta\) increases, we anticipate that \(E_{\text{W}}\) should underestimate \(E\).

Covering of the coordinate pairs \((\alpha, \beta)\) on \({\mathcal{S}}\) which represent the collection \({\mathcal{A}}\) defined in (4.41). Triangular-like regions of \({\mathcal{S}}\) above the midline of \({\mathcal{S}}\) are not covered and triangular-like regions on \({\mathcal{K}}\) below the midline of \({\mathcal{S}}\), not part of \({\mathcal{S}}\), are covered. The areas of these regions are equal, but their associated bending energies are not

The lower and upper bounds \(0< E_{\text{S}}\) and \(E_{\text{S}}< E_{\text{W}}\) on \(E_{\text{S}}\) follow directly from the consequences

and

of the inequalities \(0<\theta_{0}<\pi/2\), \(\ell>\varLambda\cos\theta _{0}\), and \(w<2\varLambda\sin\theta_{0}\), recorded in (4.17), (4.18)1, and (4.18)2.

Toward verifying the strict upper bound \(E_{\text{W}}< E\), it is first convenient to express \(E_{\text{W}}\) as an iterated integral over \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\). Since, by the definitions (4.33) and (4.35) of \(\rho\) and \(\beta _{\pm}\),

we consequently see that

and, thus, notice from (5.15) that \(E_{\text{W}}\) can also be expressed as a double integral:

Comparing (5.24) to the curvilinear parametrization (5.11) of \(E\), we recognize that \(E_{\text{W}}\) and each of the terms on the right-hand side of (5.11) share the same essential structure. Moreover, \(E_{\text{W}}\) differs from the middle term on the right-hand side of (5.11) only by the limits of integration of the outermost integral.

To simplify the study of the difference \(E-E_{\text{W}}\), it is convenient to introduce \(U\) defined by

Thus, using (5.25) in (5.11) and (5.24), we obtain succinct expressions,

and

for the bending energy and the Wunderlich [3, 4] functional of the ribbon \({\mathcal{S}}\) obtained by isometrically deforming the rectangular strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) to conform to the right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\). Referring to the definitions (4.38), (4.39), and (4.40) of \({\mathcal{T}}_{c}\), \({\mathcal{T}}_{0}\), and \({\mathcal{T}}_{\ell}\), we find that the difference \(E-E_{\text{W}}\) can be expressed as

To make further progress, we employ changes of variables that convert each integral contributing to the second expression for \(E-E_{\text{W}}\) in (5.28) to an integral over the rectilinear coordinates \((x_{1},x_{2})\). Toward this, we first introduce \(\bar{U}\), \(\hat{U}\), and \(\check{U}\) defined by

and

Next, recalling the relations (4.20) determining the curvilinear coordinates \((\alpha,\beta)\) corresponding to the rectilinear coordinates \((x_{1},x_{2})\) of each material point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in \({\mathcal{D}}\), we write, with a slight abuse of notation,

With the change of variables \((\alpha,\beta)\to(\tilde{\alpha }(x_{1},x_{2}),\tilde{\beta}(x_{1},x_{2}))\), the first and third terms in the ultimate expression for \(E-E_{\text{W}}\) on the right-hand side of (5.28) transform to

and

where \(\ell_{-}\) and \(\zeta\) are defined by

Similarly, with the change of variables \((\alpha,\beta)\to(\tilde {\alpha}(-x_{1},-x_{2}),\tilde{\beta}(-x_{1},-x_{2}))\), the second term in the ultimate expression for \(E-E_{\text{W}}\) on the right-hand side of (5.28) transforms to

while, with the change of variables \((\alpha,\beta)\to(\tilde{\alpha }(2\ell-x_{1},-x_{2}),\tilde{\beta}(2\ell-x_{1},-x_{2}))\), the final term in the ultimate expression for \(E-E_{\text{W}}\) on right-hand side of (5.28) transforms to

Next, since, by (4.18)2, \(x_{1}\tan\theta_{0}\le w/2\) if \(0< x_{2}< w\cot\theta_{0}/2\) and

for any choice of \((x_{1},x_{2})\) in the region of integration of \(\hat {U}(0,w\cot\theta_{0}/2;x_{1}\tan\theta_{0},w/2)\) and \(\bar {U}(0,w\cot\theta_{0}/2;x_{1}\tan\theta_{0},w/2)\), we find that

Similarly, since, by (4.18), \(\zeta(x_{1})\le w/2\) for \(\ell_{-}< x_{1}<\ell\) and

for any choice of \((x_{1},x_{2})\) in the region of integration for \(\check{U}(\ell_{-},\ell;\zeta(x_{1}),w/2)\) and \(\bar{U}(\ell _{-},\ell;\zeta(x_{1}),w/2)\), we find that

Finally, using (5.39) and (5.41), we conclude that the second inequality, namely \(E_{\text{W}}< E\), in (5.19) holds.

Our analysis demonstrates that Wunderlich’s [3, 4] functional \(E_{\text{W}}\) underestimates the bending energy \(E\) of a conical ribbon \({\mathcal{S}}\) obtained by applying the isometric deformation \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{y}}\) defined in (4.19) to the rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) for all admissible choices of the length and width, \(\ell\) and \(w\), of \({\mathcal{D}}\), the angle \(\theta_{0}\) determining the inclination of the referential ruling that emanates from the left-hand endpoint of the midline of the strip, and the length \(\varLambda\) of the generator of the portion of the right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\) that lies above the \((x_{1},x_{2})\)-plane. Additionally, Sadowsky’s [5, 6] functional underestimates Wunderlich’s [3, 4] functional in an analogous fashion.

5.1.6 Illustrative Comparisons

To highlight the implications of the bounds established in Sect. 5.1.5, we restrict attention to situations where the isometric deformation of \({\mathcal{D}}\) to \({\mathcal{S}}\) is such that the distance \(\varLambda\) between the left-hand endpoint \((x_{1},x_{2})=(0,0)\) of the midline of \({\mathcal{S}}\) and the apex \((x_{1},x_{2})=(\varLambda\cos\theta_{0},\varLambda\sin\theta_{0})\) of \({\mathcal{K}}\) is comparable to the length \(\ell\) of \({\mathcal{D}}\), so that

Granted this provision, we first determine how \(E\) and \(E_{\text{S}}\) behave for \(w\ll\ell\) and \(w\to 2\varLambda\sin\theta_{0}\) corresponding, respectively, to situations in which the width of \({\mathcal{D}}\) is significantly smaller than its length \(\ell\) and in which the width of \({\mathcal{D}}\) approaches the maximum value dictated by (4.18)2, in which case a point on the upper edge of \({\mathcal{S}}\) closely approaches the apex of \({\mathcal{K}}\).

Treating \(E\) and \(E_{\text{W}}\) as functions of \(w/2\ell\), we compute their Taylor expansions about \(w/2\ell=0\). Truncating these expansions at \(O((w/2\ell)^{5})\) and invoking the expression (5.18) for \(E_{\text{S}}\), we obtain

and

with \(f\) and \(g\) defined according to

and

Eliminating \(E_{\text{S}}\) between (5.43) and (5.44), we also see that

We therefore infer from (5.43), (5.44), and (5.47) that, for \(w\ll\ell\), each of the differences \(E-E_{\text{W}}\), \(E-E_{\text{S}}\), and \(E_{\text{W}}-E_{\text{S}}\) increases with the cube of \(w/2\ell\). Although the expansions of \(E\) and \(E_{\text{W}}\) about \(w/2\ell=0\) have the same leading-order term—the Sadowsky [5, 6] functional \(E_{\text{S}}\), we also see from (5.47) that the coefficients of the cubic terms in those expansions differ. We may use trigonometric identities in conjunction with the restrictions (4.17) and (4.18)1 on \(\theta _{0}\) and \(\ell/\varLambda\) to show that the coefficient \(f(\ell/\varLambda,\theta_{0})\) defined in (5.45) is positive and thus, with reference to (5.47), confirm that, consistent with the bound \(E_{\text{W}}< E\) established in Sect. 5.1.5, \(E>E_{\text{W}}\) for \(w\ll\ell\).

Next, to obtain information about the behavior of \(E\) as \(w\to2\varLambda \sin\theta_{0}\), we apply the asymptotic relation (Lewin [10, equation (2.6)])

to (5.7) and thereby deduce that

Specializing the expression (5.16) for \(E_{ \text{W}}\) to incorporate the assumption (5.42) and recalling, from (4.17) and (4.18)1, that \(0<\theta_{0}<\pi/2\) and \(\varLambda\cos \theta_{0}<\ell\), we see that

and thus that \(E\) and \(E_{\text{W}}\) exhibit identical divergent behavior as \(w\to2\ell\sin\theta_{0}\). However, consistent with the bound \(E_{\text{W}}< E\) established in Sect. 5.1.5, \(E_{\text{W}}\) underestimates \(E\) even for values of \(w\) less than but approaching \(2\varLambda\sin\theta_{0}\). Since Sadowsky’s [5, 6] functional is meaningful only for \(w\ll\ell\), it would be unreasonable to expect that \(E_{\text{S}}\) would share the behavior of \(E\) and \(E_{\text{W}}\) on passing to the limit \(w\to2\ell\sin\theta_{0}\). Indeed, the value of \(E_{\text{S}}\) as \(w\to2\ell\sin\theta_{0}\) is finite.

For illustrative purposes, we hereafter confine attention to the particular situation in which the generators of the portion of the right circular conical surface \({\mathcal{K}}\) that lie above the plane spanned by \(\boldsymbol{\imath}_{i}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\imath}_{2}\) and the rectangular material strip \({\mathcal{D}}\) are of equal length, so that

Granted that (5.51) holds and recalling again from (4.17) that \(0<\theta_{0}<\pi/2\), we notice that the restrictions (4.18) involving \(\ell\), \(w\), and \(\varLambda \) simplify to a single requirement:

Using (5.51) in the expressions (5.7) and (5.16) for \(E\) and \(E_{\text{W}}\), we thus have that

Similarly, using (5.51) in the expressions (5.16) and (5.18) for \(E_{\text{W}}\) and \(E_{\text{S}}\) while bearing in mind that \(\arctan (\cot\theta_{0})=\theta_{0}/2\) for \(0<\theta_{0}<\pi\), we have that

Taking note of the asymptotic expression (5.47) for the small \(w/2\ell\) behavior of \(2(E-E_{\text{W}})/\mu \cot ^{2}\varphi \) and its precursor (5.44) for \(2(E_{\text{W}}-E_{\text{S}})/\mu \cot ^{2}\varphi \), we consider the dimensionless measures

of the differences (5.53) and (5.54), where, by (5.45) and (5.46),

Since \(E>E_{\text{W}}>E_{\text{S}}\), \(I\) and \(J\) respectively represent scaled measures of the absolute errors incurred in approximating \(E\) by \(E_{ \text{W}}\) and \(E_{\text{W}}\) by \(E_{\text{S}}\).