Abstract

Early blight, caused by the fungus Alternaria solani, is a common foliar disease in potato. Quinone outside inhibitor (QoIs) fungicides have commonly been used against A. solani. To avoid or delay development of fungicide resistance it is recommended to alternate or combine fungicides with different modes of action. Therefore, we compared two different fungicide programs against early blight in field trials and studied within season changes in the pathogen population. An untreated control was compared with treatments using azoxystrobin alone and with a program involving difenoconazole followed by boscalid and pyraclostrobin combined. Isolates of A. solani were collected during the growing season and changes in the population structure was investigated. We also screened for the amino acid substitution in the cytochrome b gene and investigated changes in sensitivity to azoxystrobin. Treatment with azoxystrobin alone did not improve disease control in 2014 when the disease pressure was high. However, lower severity of the disease was observed after combined use of difenoconazole, boscalid and pyraclostrobin. The efficacy of both fungicide treatments were similar during the field trial in 2017. Two mitochondrial genotypes (GI and GII) were found among isolates, where all isolates, except two, were GII. All GII isolates had the F129 L substitution while the two GI isolates were wild type. Population structure analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) of amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP) data revealed within season changes in the A. solani populations in response to fungicide application. Isolates with the F129 L substitution had reduced sensitivity to azoxystrobin in vitro and their sensitivity tended to decrease with time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The genus Alternaria is found in a wide range of environments worldwide. One of the most economically important members of the genus is Alternaria solani (Ellis & G. Martin) L. R. Jones & Grout 1896, which causes early blight disease in potato and tomato. Due to heavy defoliation during epidemics, the disease can cause major yield losses (Shtienberg et al. 1990; Rotem 1994; Leiminger and Hausladen 2014). This fungus is also commonly found in commercial potato production fields in Sweden. Although early blight symptoms were found in fields every year, traditionally A. solani was considered to be of minor importance in Sweden. However, during recent years several reports have revealed increasing problems associated to early blight in Sweden, particularly in the south-eastern part of the country (Andersson and Wiik 2008; Edin and Andersson 2014). Personal communications with potato growers and advisors confirmed the increasing problems and Edin et al. (2019) confirmed in their study that A. solani is the causal agent of early blight in south-eastern Sweden.

Early blight in potato, and other diseases caused by Alternaria spp., have typically been controlled by repeated fungicide applications (Horsfield et al. 2010). One of the commonly used fungicide groups are the quinone outside inhibitors (QoIs). These fungicides have been widely used for many years due to their broad-spectrum protection, reduced environmental effects and excellent yield benefits (Bartlett et al. 2002). QoIs prevent electron transport in mitochondrial respiration by binding to the Qo site of the cytochrome b (cytb) complex, and thus, inhibit ATP synthesis (Bartlett et al. 2002). However, due to this specific mode of action, there is a high risk of the development of fungicide resistance as a result of evolution in the pathogen population. Indeed the development of fungicide resistance in pathogen populations has been well documented (Chin et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2003; Avila-Adame et al. 2003; Pasche et al. 2005; Leiminger et al. 2014).

A shift towards reduced fungicide sensitivity in A. solani was first observed in the USA (Pasche et al. 2004). Frequent applications of azoxystrobin led to mutations in the mitochondrial target gene, causing a substitution of an amino acid, in the cytochrome b protein. This substitution prevents fungicide binding and thus reduces sensitivity. Only the F129 L substitution has been found in A. solani, with either of the three-nucleotide mutations TTA, CTC and TTG at codon position 129. This leads to an amino acid substitution from phenylalanine (F) to leucine (L), which reduces the sensitivity but does not result in complete loss of field efficacy to QoIs (Pasche et al. 2005). Leiminger et al. (2014) reported, based on sequence analysis, that individuals within A. solani populations in Germany have two structurally different cytb genes (genotype I, GI, and genotype II, GII). The structure of GI consisting of five exons and four introns and the putative mutation site (F129 L) is located at the beginning of exon 2, wherein GII, intron 1 was missing, and putative F129 L substitution was located at the exon 2 as far as codon G131 (Leiminger et al. 2014). The F129 L substitution in their study was only found in GII isolates. However, in the recent studies, the F129 L substitution has been found in samples with the GI genotype, although at much lower frequencies (Edin et al. 2019). Several reports also indicate that application of QoIs no longer provides consistent efficacy against Alternaria-species (Pasche et al. 2005; Luo et al. 2007; Rosenzweig et al. 2008). In Sweden, QoIs first exhibited effective management of early blight and increased potato yields (Andersson and Wiik 2008). However, observations during the last few years show a reduced efficacy of QoI fungicides in the field, especially in the area around Kristianstad in the south-eastern part of Sweden (personal communication with growers and advisors). Moreover, high frequencies of GII containing the F129 L substitution have been identified among the isolates collected in this area (Odilbekov et al. 2016; Edin et al. 2019).

Studies of the genetic structure of pathogen populations are important for disease management strategies and are important tools to aid our understanding of epidemiology and host-pathogen coevolution. Information from such studies reflects the potential for change in the pathogen population, such as the development of fungicide resistance (McDonald and Linde 2002; van der Waals et al. 2004). High genetic variation in the population of A. solani has been found in various studies using a variety of different molecular markers, such as isozyme analyses (Petrunak and Christ 1992), random amplified microsatellite (RAMS) (van der Waals et al. 2004), Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (Leiminger et al. 2013) and simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers (Meng et al. 2015).

Amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP, Vos et al. 1995) is a highly reproducible PCR-based method for DNA-fingerprinting, which can produce a large number of polymorphic loci. This method is a valuable technique for population variability studies, especially in species where sequence information is not available. AFLP has been successfully used to previously investigate the population variability in A. solani (Lourenco et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2012; Odilbekov et al. 2016).

To avoid or at least delay development of fungicide resistance in pathogen populations it is recommended to alternate or combine fungicides with different mode of action. This strategy is supposed to lower the selection pressure for fungicide resistant strains. The approval of fungicides depends on its efficacy to control the disease, durability of the effect, and various toxicological characteristics. Treatment strategies, i.e. how frequent and at what rate the fungicides can be applied, are then built on basis of above characteristics. Comparing different chemicals given at the same times would not be very relevant since that will never be done in practice. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the general genetic shifts in the A. solani population during the season as a response to two different practical fungicide application programs by using AFLP markers. Untreated plots were compared with plots treated with a QoI fungicide (azoxystrobin) only, or plots treated with combinations/alterations between a QoI (pyraclostrobin), a SDHI (boscalid) and a triazole fungicide (difenoconazole). Sampled isolates were also analysed by sequencing the gene encoding cytochrome b in order to identify changes in the frequency of any amino acid substitution relevant for QoI sensitivity. Furthermore, changes in sensitivity to azoxystrobin were investigated.

Materials & methods

Field trial and sample collection

The two field experiments in 2014 and 2017, respectively, were performed at Nymö, about 15 km east of Kristianstad. Tubers of starch potato cultivar Kuras were planted (April 26, 2014, and April 25, 2017) in a randomized complete block design with four blocks and each plot had five rows of 10 m length. Within each block, the different treatments were randomly distributed. An untreated control (UTR) was compared with two different fungicide treatment programs (Table 1). All plots were treated with recommended doses of Revus (two times) followed by Ranman Top against late blight at least every week and with an insecticide once. UTR had no further treatments. In addition to late blight fungicides in Treatment 1 (TR1), we applied Revus Top (in place of Revus in the untreated control) two times followed by Signum four times. In Treatment 2 (TR2), Amistar was applied twice, alongside the standard Revus or Ranman Top applications against late blight. All treatments were fulfilled according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. No inoculation was implemented but to ensure that the symptoms observed during assessment were due to infection of A. solani the field was evaluated by fungal isolation from typical early blight lesions. Disease severity was assessed by percent of infection, i.e. percent of remaining green leaf area that had necrotic spots was assessed visually according to the EPPO-scale (OEPP/EPPO 2004) four times in 2014 (July 30, August 9, August 19, September 2) and five times in 2017 (August 22, 29, September 4,10,17,). The relative area under the disease progress curve (rAUDPC) was calculated as a measurement of disease severity over the season. Leaflets with symptoms of early blight were collected four times in 2014 and two times in 2017 during the field trials (Table 2). From each plot, leaflet samples were randomly collected from the middle rows and the leaflets were placed in small paper bags and air-dried. Four leaflets per plot and collection event were used in the analyses. The three middle rows were harvested for yield measurements.

Fungus isolation

Small sections (3–4 mm2) from the margins of early blight lesions were cut out from the leaf samples and sterilized in 1% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min, followed by washing twice in sterile distilled water. The leaflet sections were placed on water agar containing the antibiotic chlortetracycline, (100 μg mL−1) and incubated for 3–4 days in darkness at room temperature to stimulate sporulation. A single conidium was picked up with a thin needle directly from the infected leaf tissue under a stereomicroscope and placed on new potato dextrose agar plate for germination. After germination and sporulation, sterile distilled water was added to the culture to allow detachment of spores and 50 μl of the resulting A. solani spore suspension was spread onto a new water agar plate and incubated until sporulation. A single conidium was again picked directly from the water agar plate with a tiny needle under a stereomicroscope and placed on new potato dextrose agar for germination. Morphological identification of A. solani isolates was performed based on Simmons (2007) and the identifications were also confirmed with PCR based methods (Pasche et al. 2005; Edin 2012). An A. solani isolate from our previous work (Odilbekov et al. 2016) was used as reference isolate. Moreover, all isolates were compared for one closely related species, Alternaria linariae¸formerly Alternaria tomatophila, using specific primers (Gannibal et al. 2014). In total, 143 isolates collected in 2014 and 86 isolates collected in 2017 were used in the present work.

DNA extraction and identification of substitutions in cytochrome b

Single-spore isolates were grown in a liquid medium (10 g sucrose, 2 g yeast extract, 15 mM KH2PO4, 0.4 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 1.5 μM ZnSO4.7H2O, 1.8 μM FeCl3.6H2O, and 2.5 μM MnCl2. H2O) in 40 ml flasks under continuous agitation (60 rpm). After eight days of incubation at room temperature, the mycelium was washed twice with distilled water, freeze-dried and stored at −80 °C. Total genomic DNA was extracted using the Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Fermentas, Lithuania) according to manufacturer’s instruction and stored at −20 °C in 100 μL of ddH2O. DNA quality was checked by electrophoresis using 1% agarose gel visualised with ethidium bromide and the concentration was adjusted to 100 ng μl−1 using a Nanodrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc. DE, USA). Identification of substitutions in the gene encoding cytochrome b for the GI genotype was based on methods described by Edin (2012) and for identification of the GII genotype primers developed by Pasche et al. (2005) were used. DNA of all isolates, confirmed as A. solani, was amplified in a reaction volume of 50 μL. The PCR conditions were the same for DNA amplification of both genotypes except that the annealing temperature for GII was 54 °C (Edin et al. 2019). An American GII (US4) isolate was used as positive control for GII and a Swedish sequenced one for GI. The PCR amplification products were analysed using electrophoresis (1% agarose gel stained with Nancy-250 (Sigma-Aldrich, MO USA)). The PCR-products were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s manual and sequenced at Macrogen Inc. Europe, Amsterdam, NL.

In vitro sensitivity test

For sensitivity tests, five GI wild-type isolates from 2011 and five GII isolates from each treatment of the first (June 2, 2014) and last collection time (September 2, 2014) were evaluated. In addition, isolates from the last collection time points for all treatments between 2014 and 2017 were evaluated. Spores of A. solani were produced according to Odilbekov et al. (2014) and the spore suspension was adjusted to 2 × 104 conidia mL−1. In vitro sensitivity tests were performed as described by Leiminger et al. (2014) in duplicates. Briefly, the spore suspension (50 μl) of each isolate was spread onto the surface of water agar plates containing fungicides (Azoxystrobin, Sigma–Aldrich) at different concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 μg mL−1) and 100 mgL−1 salicylhydroxamic acid (SHAM). Petri dishes with water agar and SHAM were used as controls. The plates were incubated (continuous light for 5 h at 28 °C) and thereafter germination of 100 conidia was assessed. Fungicide sensitivity was measured as the concentration at which spore germination was inhibited by 50% relative to the untreated control (EC50 value) and was determined for each isolate.

AFLP analysis

DNA digestion (using enzymes MseI and EcoRI), ligation, pre-amplification and selective amplification were performed with the AFLP Microbial Fingerprinting Kit (Applied Biosystems, CA USA) based on a modified manufacturer’s protocol according to Vos et al. (1995). The primers used for selective amplification were E + AA/M + A, E + AC/M + C, E + AA/M + C, E + AA/M + G and E + AT/M + A, selected based on the degree of polymorphism (Lourenco et al. 2011). The amplified PCR products were analysed on ABI 3730 capillary DNA analysers (Applied Biosystems) at The University of Copenhagen, Denmark. Genemarker (Softgenetics®, PA, USA) software was used for visualizing and analyzing the data. All bands were scored manually considering both the gel image and the peak height using default settings with the recommended threshold intensity. Bands between 60 and 500 base pairs were scored as either present “1” or absent “0”. Only bands that could be scored clearly were included in the AFLP analysis.

Data analysis

AUDPC was calculated based on the following standard formula:

Where Yi is disease severity in percent at the ith observation, Xi is time (days) at the ith observation and n is the total number of observations. The relative AUDPC (rAUDPC) was calculated by dividing AUDPC by the total area during the assessment period, assuming 100% disease from the start. Minitab software (Version 17.1.0) was used for statistical calculations. Differences in percent of infection for plants in the field experiments as well as differences in fungicide sensitivity were investigated with ANOVA (PROC GLM). Comparisons of mean values were conducted using Tukey’s test. POPGENE version 1.32 was used to generate Nei’s gene diversity (H). NTSYSpc (version 2.2) statistical package was applied to perform Nei and Li (1979) similarity matrix and principal coordinate analysis. STRUCTURE software version 2.3.4 (Pritchard et al. 2000), STRUCTURE HARVESTER (Earl and vonHoldt 2012) and DISTRACT version 1.1 (Rosenberg 2004) were used to illustrate the population structure with colour fields. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was performed according to Excoffier et al. (2005) using Arlequin 3.0.

Results

Field experiments

Symptomatic leaflets were first identified at the beginning of June in 2014, and at the beginning of July in 2017. Alternaria solani was isolated at a low frequency from those lesions. Samples collected later during each field season were almost all verified as early blight lesions. The epidemic phase of the disease started at the end of July in 2014 when the percent of diseased leaf area increased heavily in UTR. In TR2 (azoxystrobin treatment) the infection was almost as high as in the UTR and was not significantly different from the control at the two last scoring dates. However, a significant (p < 0.01) lower disease rate was observed in TR2 at the second scoring date (Fig. 1a). In TR1 (difenoconazole + boscalid and pyraclostrobin), the rate of disease development was significantly lower (p < 0.01) than that of both the UTR and treatment TR2. In 2017, the epidemic phase of the disease started at the end of August, approximately one month later than in 2014 (Fig. 1b). The percentage of infection was significantly higher in the UTR than in the other two treatments (TR1 and TR2) (p < 0.01) at all three scoring dates. However, no difference was observed between TR1 and TR2 in 2017. Yield measurement results also revealed significant differences between the treatments in 2014 (Table 3, p < 0.01). TR1 gave a significantly higher yield compared to the UTR and TR 2. However, no significant differences in yield were found between the treatments in 2017.

Disease development curves (a - 2014 and B - 2017) in potato trials with different treatments against early blight. UTR = Untreated control. TR1 = treatment 1: Difenoconazole two times followed by four times boscalid and pyraclostrobin combined. TR2 = treatment 2: Azoxystrobin two times. Means followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukeys’s test. The arrows indicate the dates of different fungicides application

Substitution in cytochrome b and sensitivity test

Based on the cytb gene structure, two different genotypes (GI and GII) were found among the A. solani isolates (Table 2). In the samples collected in 2014, only two isolates were classified as GI while the other 141 isolates were classified as GII (where the F129 L substitution was present). All the isolates from 2017 were GII. All of the GII isolates had the TTA nucleotide substitution (F129 L), whereas the two GI isolates from 2014 had a wild type cytb gene. All tested isolates that contained the F129 L substitution had reduced sensitivity to azoxystrobin compared to wild-type isolates (Figs. 3 and 4). The means of EC50 - values, based on germination rates in in vitro test, varied between 0.15–1.4 μg mL−1 for the isolates with the F129 L substitution, whereas in wild-type isolates the EC50−-values varied between 0.01–0.12 μg mL−1. The difference between wild type and F129 L isolates was statistically significant (p < 0.01) according to Tukey test (Fig. 2). Sensitivity appeared to change over time within the pathogen population; isolates from the last collection time points for TR1 and TR2 (in both seasons) revealed a significant difference (p < 0.01) in sensitivity to azoxystrobin (Fig. 3) compared to other isolates. Isolates from 2017 with the F129 L substitution had even lower sensitivity to azoxystrobin than any of the previously identified isolates, as indicated by EC50 values of up to more than 3 μg mL−1.

Mean of EC50 values for wild type and F129 L substitution isolates of Alternaria solani from different treatments and collection times obtained from in vitro sensitivity tests of azoxystrobin. WT = wild type isolates were collected in 2011. Time 1: Isolates were collected in July 18/2014. Time 3: Isolates were collected in September 2/2014. UTR = untreated control, but treated against late blight. TR 1 = treatment 1: Difenoconazole two times followed by four times boscalid and pyraclostrobin combined. TR 2 = treatment 2: azoxystrobin two times. Means followed by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test

Mean of EC50 values for isolates of Alternaria solani from 2014 and 2017 possessing the F129 L substitution obtained from in vitro sensitivity tests of azoxystrobin. WT = wild type isolates were collected in 2011. UTR = Untreated control but treated against late blight. TR 1 = treatment 1: Difenoconazole two times followed by four times boscalid and pyraclostrobin combined. TR 2 = treatment 2: Azoxystrobin two times. (*2 sample t-test, p < 0.05)

Population structure

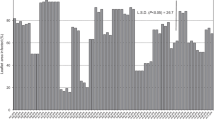

The mean gene diversity (H) among the isolates in all treatments was slightly higher in samples collected at the time points 1 and 2 (0.20 and 0.19 respectively) compared to those sampled at the time points 0 and 3 in 2014 (Fig. 4). In 2017, the gene diversity was higher among the isolates from the UTR 2017 compared to isolates from TR1 and Time 2 in TR2 (Fig. 4). Lower gene diversity was observed at Time 2 in comparison with Time 1 in TR1 and TR2.

Structure and gene diversity analysis of isolates of Alternaria solani from different years, fungicide treatments and collection times. UTR = Untreated control but treated against late blight. TR = Treatment 1: Difenoconazole two times followed by four times boscalid and pyraclostrobin combined. TR2 = Treatment 2: Azoxystrobin two times. Time 0: Isolates were collected before all the fungicide treatments in June 2/2014. Time 1: Isolates were collected in July 18/2014. Time 2: Isolates were collected in August 19/2014.Time 3: Isolates were collected in September 2/2014. Time 1*: Isolates were collected in August 14/2017. Time 2*: Isolates were collected in September 12/2017. h = Nei’s diversity index

The STRUCTURE analyses of isolates from the UTR in 2014 indicated the presence of two main clusters (Fig. 4). However, the predicted population structure of the isolates revealed partial membership to more than one population, and none of the isolates showed membership to only one population. Analysis of molecular variances (AMOVA; Table 4) revealed that in untreated plots, the highest percentage of between population variations occurred from Time 0 to Time 3 (23%, p < 0.01) as well from Time 0 to Time 1 (15%, p < 0.01). There was a lower percentage difference between population variation from Time 1 to Time 2 as well as from Time 2 to Time 3. The STRUCTURE analyses also showed two main clusters, which have partial membership to more than one population (Fig. 4, TR1, 2014). AMOVA analysis in TR1 revealed that the highest percent between population variation was from Time 0 to Time 3 (23%, p < 0.01) as well as from Time 0 to Time 1 (21%, p < 0.01), whilst a lower percentage between population variation was found from Time 1 to Time 2 and from Time 2 to Time 3 (Table 4). STRUCTURE analyses of TR2 (Fig. 4, TR2, 2014) displayed two main clusters. The predicted population structure for the isolates from TR2 indicated a change over time, whereas isolates from Time 3 displayed membership to only one population. The mean gene diversity among isolates from this treatment was also lower at Time 3 (0.09%) compared with the other treatments. AMOVA analysis indicated a higher percentage of variation between populations from Time 0 to Time 3 (56%, p < 0.00), from Time 1 to Time 3 (52%, p < 0.00) and from Time 2 to Time 3 (45%, p < 0.00) while among population variation between Time 0, 1 and 2 was much lower (Table 4).

The STRUCTURE analyses of isolates collected from the UTR in 2017 showed the presence of three main clusters (Figs. 4, 2017). However, only two main clusters were found in TR1 and TR2 (Fig. 4, TR1 and 2, 2017). In all treatments, the predicted structure also revealed partial membership to more than one population. The AMOVA analysis revealed that the highest percentage of between population variations occurred from Time 1 to Time 2 in TR1 (8.05%, p < 0.03, Table 5) and TR2 (8.15%, p < 0.02, Table 5). However, there was a lower percentage of population variation from Time 1 to Time 2 (4.25%, Table 5) in the UTR.

A comparison was made between the isolates that were collected in 2014 before all the fungicide treatments (Treatment 0) and the isolates from the last time point for all treatments (UTR and TR1 and 2) using principal component analysis (PCA). The first dimension explained 63% and the second dimension 7% of the variation, respectively. The PCA plot shows that isolates from Treatment 0 grouped together and that there was a shift along the second dimension in all treatments (Fig. 5a). All, except one, of the isolates from TR2 grouped together, which was different from the other treatments. We were not able to isolate A. solani from the field before the first fungicide treatment in 2017.

PCA of Alternaria solani isolates collected from different fungicide treatments at the last collection time (a - September 2, 2014, and b - September 12, 2017) TR0 = Treatment 0: Isolates were collected before all the fungicide treatment. UTR = Untreated control but treated against late blight. TR1 = treatment 1: Difenoconazole two times followed by four times boscalid and pyraclostrobin combined. TR2 = treatment 2: Azoxystrobin two times

Discussion

The population of A. solani in the investigated fields was dominated by isolates with the F129 L substitution and only two wild-type isolates were found among the investigated isolates from both years. Sensitivity tests revealed that isolates from 2014 possessing the F129 L substitution, were ten times less sensitive to azoxystrobin compared to the wild type (Fig. 2) and there was a shift to even lower sensitivity during the growing season in 2017 (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the field trials clearly showed that significant disease control was not obtained by using azoxystrobin only, indicating that the substitution may have a strong influence on Qol fungicide efficacy in field situations (Fig. 1). Combined use of difenoconazole, boscalid and pyraclostrobin had much higher efficacy in 2014 but not in 2017. The reason for that is probably the development of resistance also against boscalid (which is the active ingredient. in Signum). In 2017, we discovered mutations associated with fungicide resistance against boscalid that had not been detected in 2014 (unpublished data). The higher efficacy of azoxystrobin in 2017 compared to 2014 may be due to the lower infection pressure in 2017. Based on field trials, Pasche and Gudmestad (2008) suggested that application of QoI fungicides against populations of A. solani dominated by the F129 L substitution would not provide enhanced disease control in comparison with standard protectant fungicides. The occurrence of the F129 L substitution among isolates in the field is likely to be a result of repeated fungicide application regimes with QoIs performed by the grower during the previous crop rotations. Repeated exposure of the pathogen population to this single fungicide creates a strong selection pressure, allowing individuals with the substitution a fitness benefit for survival (Pasche et al. 2004; Rosenzweig et al. 2008). As shown in the USA, within a few years of intensive Qol fungicide applications (up to six applications per season), early blight disease control was severely affected. Once the substitution arose in the population there was strong selection pressure for its persistence and thus Qols were quickly rendered ineffective against A. solani. Indeed, one study reported a 10–12 fold shift in sensitivity to azoxystrobin (Pasche et al. 2005). Reduced sensitivity to azoxystrobin was also revealed in Germany, where up to three applications per season were allowed, but to a lower degree compared to the situation in the USA (Leiminger et al. 2014).

According to the present study, all GII isolates collected from this field had the F129 L substitution, while wild-type was only found in the two GI isolates (Table 2). These results are in accordance with our previous study where the amino acid substitution was found only in GII isolates (Odilbekov et al. 2016). Similar results were also obtained in Germany, where the F129 L substitution was identified only in genotype II (Leiminger et al. 2014). In our previous study (Odilbekov et al. 2016) we found high frequencies of isolates with the F129 L substitutions in the area around Kristianstad in 2011, while in another area, around Kalmar, the F129 L substitution was not found. Both of the areas are located in the south-eastern part of Sweden, where the earliest analysed isolate with F129 L was collected in 2009 (Edin et al. 2019). An original objective was to also study changes in the frequency of isolates with the F129 L mutation. We expected that the field in Nymö (Kristianstad area) would have a low frequency of isolates with F129 L substitution when this experiment started. However, all GII isolates in the starting population carried the F129 L substitution and therefore it was not possible to investigate the effects of fungicide programs on within-season changes in F129 L frequency in the A. solani population. Interestingly, the sensitivity to azoxystrobin appeared to be significantly lower in isolates from 2017 compared to 2014. EC50-values in isolates with the F129 L substitution were about ten times higher than for wildtype isolates in 2014 but in 2017 isolates with up to 40 times higher EC50-value were found. Besides F129 L no other mutations in the cytochrome b gene associated with azoxystrobin resistance are known in A. solani. Therefore, one might speculate if also metabolic resistance mechanisms could have evolved in the pathogen besides the target site resistance.

As well as quantifying fungicide resistance, this work also aimed to investigate general genetic changes in the A. solani population during a cropping season in response to different fungicide programs. Structure analysis and PCA results (Figs. 4 and 5) based on our AFLP data confirmed the presence of mainly two groups of isolates. The average gene diversity (H) from the current field experiments was 0.17, which is lower to the overall H value (0.19) in the previous study (Odilbekov et al. 2016). Also, in both studies, a high percentage of the variation was observed within populations (Tables 4 and 5). Probably the movement of the host material (tubers) between the fields, may have contributed to the variability among isolates (Weir et al. 1998). However, tuber infection has been very rarely observed in Sweden and the primary mode of dispersal may be spore transport in the soil during tillage, planting and covering of the potatoes.

Interestingly, in 2014, isolates from TR2 (azoxystrobin application) showed a different pattern, particularly at the end of the season in comparison to the UTR and TR1 (Fig. 5, TR2, 2014). The result indicated that application of azoxystrobin alone against A. solani in the field could result in population changes within a season. However, in 2017 azoxystrobin alone (TR2) did not affect the population more than the other fungicide treatment (TR1). In 2017 the disease epidemic started much later and high infection rates were first obtained when the crop started to senesce. Thus, the infection pressure was much lower in 2017 than in 2014. The presence of genotypes resistant to boscalid in 2017 may have also affected selection processes in the population (unpublished results). Still, both fungicide treatments appeared to cause changes in the A. solani population within the season compared to the untreated control. In 2017, it was only one month between the first and the second sampling and apparently the population structure can be affected in that short time. Studies of population changes as a response to treatment strategies, therefore, merit further studies.

There is very little known about how far air-borne conidia of A. solani can spread within and between fields. The source of inoculum in the experimental field could be spores from plant debris in the soil from the previous years in the same or nearby fields. In this experiment, all plots that were treated with different fungicides were close to each other and a vast spread of spores between plots would result in an evenly distributed population. However, the results indicated that population changes happened especially at the end of the season in response to different fungicide treatments. This may indicate that the main dispersal of spores is very local. There appeared to be a change in the population over time in all treatments (Fig. 5). That may be due to selection for isolates adapted for plant infection during the cropping season, but the selection during winter for saprophytic growth on plant debris may be even more important.

Fungi are always under adverse conditions where different factors are constantly changing their environments (Rotem 1994). Environmental conditions and agricultural practices are probably important factors leading to the selection of particular mutated isolates. For example, four mutation events were visualised in a study of European sub-populations of Zymoseptoria tritici, which had occurred due to QoI fungicide application, disproving the hypothesis that a single mutant haplotype appeared and spread across other regions (Torriani et al. 2009). Natural mutations may occur more frequently in asexually reproducing isolates than in sexually reproducing ones (Rogers 2007). Moreover, because of that, large numbers of spores are produced during different times within a growing season and thereby many opportunities for genetic mutation occur (Weber and Halterman 2012).

QoI fungicides take a significant place in disease management on different crops in many countries (Bartlett et al. 2002). In Sweden, the substitution F129 L, associated with resistance to QoI fungicides, is present in most potato growing regions (Edin et al. 2019). However, based on studies that were performed in the USA and Europe (Pasche and Gudmestad 2008; Leiminger et al. 2014; Edin et al. 2019), we believe that selection in the A. solani population will continue to rapidly emerge if the intensive applications of QoI fungicides are also continued.

In conclusion, we found that fungicides affect the population structure of A. solani within a cropping season. We also found that the sensitivity to azoxystrobin of A. solani isolates harbouring F129 L tended to increase with time. Thus, control strategies against A. solani on potato should be adjusted to decrease the selection pressure for decreased sensitivity to fungicides. The main measures are to reduce the number of sprays and by using mixtures or alternate fungicides with different modes of action (www.frac.info) that could preserve and prolong the efficacy of fungicides. There is also a need to develop alternative means of disease control that can be integrated into disease management programs and decrease the dependence on fungicides.

References

Andersson, B., & Wiik, L. (2008). Betydelsen av torrfläcksjuka (Alternaria ssp.) på potatis. Slutrapport av SLF 0455031.

Avila-Adame, C., Olaya, G., & Koller, W. (2003). Characterization of Colletotrichum graminicola isolates resistant to strobilurin-related QoI fungicides. Plant Disease, 87(12), 1426–1432.

Bartlett, D. W., Clough, J. M., Godwin, J. R., Hall, A. A., Hamer, M., & Parr-Dobrzanski, B. (2002). The strobilurin fungicides. Pest Management Science, 58(7), 649–662.

Chin, K. M., Chavaillaz, D., Kaesbohrer, M., Staub, T., & Felsenstein, F. G. (2001). Characterizing resistance risk of Erysiphe graminis f.sp tritici to strobilurins. Crop Protection, 20(2), 87–96.

Earl, D. A., & vonHoldt, B. M. (2012). Structure harvester: A website and program for visualizing structure output and implementing the Evanno method. Conservation Genetics Resources, 4(2), 359–361.

Edin, E. (2012). Species specific primers for identification of Alternaria solani, in combination with analysis of the F129L substitution associates with loss of sensitivity toward strobilurins. Crop Protection, 38, 72–73.

Edin, E., & Andersson, B. (2014). The early blight situation in Sweden - species abundance and strobilurin sensitivity. In H. Schepers (Ed.), PPO special report no 16 (pp. 83–84). The Netherlands: Lelystad.

Edin, E., Liljeroth, E., & Andersson, B. (2019). Long term field sampling in Sweden reveals a shift in occurrence of cytochrome b genotype and amino acid substitution F129L in Alternaria solani, together with a high incidence of the G143A substitution in Alternaria alternata. European Journal of Plant Pathology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-019-01798-9.

Excoffier, L., Laval, G., & Schneider, S. (2005). Arlequin (version 3.0): An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evolutionary Bioinformatics, 1, 47–50.

Gannibal, P. B., Orina, A. S., Mironenko, N. V., & Levitin, M. M. (2014). Differentiation of the closely related species, Alternaria solani and A-tomatophila, by molecular and morphological features and aggressiveness. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 139(3), 609–623.

Horsfield, A., Wicks, T., Davies, K., Wilson, D., & Paton, S. (2010). Effect of fungicide use strategies on the control of early blight (Alternaria solani) and potato yield. Australasian Plant Pathology, 39(4), 368–375.

Kim, Y. S., Dixon, E. W., Vincelli, P., & Farman, M. L. (2003). Field resistance to strobilurin (Q(o)I) fungicides in Pyricularia grisea caused by mutations in the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. Phytopathology, 93(7), 891–900.

Leiminger, J. H., & Hausladen, H. (2014). Investigations on disease development and yield loss of early blight in potato cultivars of different maturity groups. Gesunde Pflanzen, 66(1), 29–36.

Leiminger, J. H., Auinger, H. J., Wenig, M., Bahnweg, G., & Hausladen, H. (2013). Genetic variability among Alternaria solani isolates from potatoes in southern Germany based on RAPD-profiles. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 120(4), 164–172.

Leiminger, J. H., Adolf, B., & Hausladen, H. (2014). Occurrence of the F129L mutation in Alternaria solani populations in Germany in response to QoI application, and its effect on sensitivity. Plant Pathology, 63(3), 640–650.

Lourenco, V., Rodrigues, T., Campos, A. M. D., Braganca, C. A. D., Scheuermann, K. K., Reis, A., et al. (2011). Genetic structure of the population of Alternaria solani in Brazil. Journal of Phytopathology, 159(4), 233–240.

Luo, Y., Ma, Z. H., Reyes, H. C., Morgan, D. P., & Michailides, T. J. (2007). Using real-time PCR to survey frequency of azoxystrobin-resistant allele G143A in Alternaria populations from almond and pistachio orchards in California. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 88(3), 328–336.

McDonald, B. A., & Linde, C. (2002). Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 40, 349–379.

Meng, J., Zhu, W., He, M., Wu, E., Yang, L., Shang, L., et al. (2015). High genotype diversity and lack of isolation by distance in the Alternaria solani populations from China. Plant Pathology, 64(2), 434–441.

Nei, M., & Li, W. H. (1979). Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 76(10), 5269–5273.

Odilbekov, F., Carlson-Nilsson, U., & Liljeroth, E. (2014). Phenotyping early blight resistance in potato cultivars and breeding clones. Euphytica, 1–11.

Odilbekov, F., Edin, E., Garkava-Gustavsson, L., Hovmalm, H. P., & Liljeroth, E. (2016). Genetic diversity and occurrence of the F129L substitutions among isolates of Alternaria solani in South-Eastern Sweden. Hereditas, 153(1), 1–10.

OEPP/EPPO. (2004). EPPO standards. efficacy evaluation of plant protection products. In Fungicides & bactericides, vol. 2. Paris: European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization.

Pasche, J. S., & Gudmestad, N. C. (2008). Prevalence, competitive fitness and impact of the F129L mutation in Alternaria solani from the United States. Crop Protection, 27(3–5), 427–435.

Pasche, J. S., Wharam, C. M., & Gudmestad, N. C. (2004). Shift in sensitivity of Alternaria solani in response to Q(o) I fungicides. Plant Disease, 88(2), 181–187.

Pasche, J. S., Piche, L. M., & Gudmestad, N. C. (2005). Effect of the F129L mutation in Alternaria solani on fungicides affecting mitochondrial respiration. Plant Disease, 89(3), 269–278.

Petrunak, D. M., & Christ, B. J. (1992). Isozyme variability in Alternaria solani and A. alternata. Phytopathology, 82(11), 1343–1347.

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M., & Donnelly, P. (2000). Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics, 155(2), 945–959.

Rogers, P. M. (2007). Diversity and biology among isolate of Alternaria dauci collected from commercial carrot fields. http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/228656933.html.

Rosenberg, N. A. (2004). Distruct: A program for the graphical display of population structure. Molecular Ecology Notes, 4(1), 137–138.

Rosenzweig, N., Atallah, Z. K., Olaya, G., & Stevenson, W. R. (2008). Evaluation of QoI fungicide application strategies for managing fungicide resistance and potato early blight epidemics in Wisconsin. Plant Disease, 92(4), 561–568.

Rotem, J. (1994). The genus Alternaria: Biology, epidemiology, and pathogenicity, 1st ed (pp. 48–203). St. Paul: The American Phtyopathological Society.

Shtienberg, D., Bergeron, S. N., Nicholson, A. G., Fry, W. E., & Ewing, E. E. (1990). Development and evaluation of a general-model for yield loss assessment in potatoes. Phytopathology, 80(5), 466–472.

Simmons, E. G. (2007). Alternaria: An identification manual. CBS Fungal Biodiversity Centre.

Torriani, S. F. F., Brunner, P. C., McDonald, B. A., & Sierotzki, H. (2009). QoI resistance emerged independently at least 4 times in European populations of Mycosphaerella graminicola. Pest Management Science, 65(2), 155–162.

van der Waals, J. E., Korsten, L., & Slippers, B. (2004). Genetic diversity among Alternaria solani isolates from potatoes in South Africa. Plant Disease, 88(9), 959–964.

Vos, P., Hogers, R., Bleeker, M., Reijans, M., Vandelee, T., Hornes, M., et al. (1995). AFLP - a new technique for DNA-fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Research, 23(21), 4407–4414.

Weber, B., & Halterman, D. A. (2012). Analysis of genetic and pathogenic variation of Alternaria solani from a potato production region. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 134(4), 847–858.

Weir, T. L., Huff, D. R., Christ, B. J., & Romaine, C. P. (1998). RAPD-PCR analysis of genetic variation among isolates of Alternaria solani and Alternaria alternata from potato and tomato. Mycologia, 90(5), 813–821.

Zhang, F., Yang, Z., Zhu, J., Zhang, H., & Wei, W. (2012). Population structure of Alternaria solani on potato in Hebei Province. Mycosystema, 31(1), 40–49.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. The study was financed by The Swedish Farmers’ Foundation for Agricultural Research and The Swedish Board of Agriculture. LGB also acknowledges funding from the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (Future Research Leaders Program FFL5) and Swedish Research Council Formas, (Grant: 2015-00430). The Rural Economy and Agricultural Societies, Sweden is acknowledged for the performance of field experiments. We thank Åsa Lankinen for valuable comments on the manuscript. We also are grateful to Mia Mogren at Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Alnarp for laboratory assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors are declaring that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal studies

The research did not have human participants or animals involved.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Odilbekov, F., Edin, E., Mostafanezhad, H. et al. Within-season changes in Alternaria solani populations in potato in response to fungicide application strategies. Eur J Plant Pathol 155, 953–965 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-019-01826-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-019-01826-8