Abstract

This paper presents the results of a systematic scoping literature review of higher education mathematics and statistics support (MSS) evaluation focusing on its impact on students. MSS is defined as any additional organised mathematical and/or statistical aid offered to higher education students outside of their regular programme of teaching by parties within the students’ institution specifically assigned to give mathematical and/or statistical support. The objective of this review is to establish how MSS researchers investigate the effect of MSS on students and what that impact is. Based on a predefined protocol, five databases, the proceedings of eight conferences, two previous MSS literature reviews’ reference lists, and six mathematics education or MSS networks’ websites and reports were searched for publications in English since 2000. A two-round screening process resulted in 148 publications being included in the review which featured research from 12 countries. Ten formats of MSS, seven data sources (e.g., surveys), and 14 types of data (e.g., institution attainment, usage data) were identified with a range of analysis methods. Potential biases in MSS research were also considered. The synthesised results and discussion of this review include the mostly positive impact of MSS, issues in MSS evaluation research thus far, and rich opportunities for collaboration. The role MSS has and can play in mathematics education research is highlighted, looking towards the future of MSS evaluation research. Future directions suggested include more targeted systematic reviews, rigorous study design development, and greater cross-disciplinary and international collaboration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Mathematics and statistics support (MSS) is the provision of aid in mathematics, statistics, numeracy, and wider quantitative skills in higher education. It was predominantly created in response to what is referred to as the “mathematics problem” (Hawkes & Savage, 2000; Lawson et al., 2020). A large part of the mathematics problem is the more widely studied secondary-tertiary transition issue (Di Martino et al., 2023; Gueudet, 2008; Hochmuth et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2015) where students struggle to adjust to the new norms of higher education mathematics and, in particular, are underprepared to succeed. It also includes the issue of graduates being unprepared for the mathematical demands of the modern workplace. MSS seeks to support students underprepared for, and struggling with, the demand of higher education mathematics via provision of tutoring and mathematical resources. A common format of MSS is the Mathematics Support Centre (MSC), also known as tutoring or learning centres. Lawson and colleagues defined MSCs as facilities “offered to students (not necessarily of mathematics) which is in addition to their regular programme of teaching through lectures, tutorials, seminars, problems classes, personal tutorials, etc.” (2003, p. 9). A broader definition of MSS includes MSCs and mathematical support provided by MSS provisions which are not necessarily held within the academic year (e.g., bridging courses) or based in a physical centre (e.g., videos, interactive applets, and worksheets). Teaching staff also provide support in and outside of scheduled class time; for example, Alcock and colleagues’ e-proofs (Alcock et al., 2015). The definition of MSS used in this paper is any additional organised mathematical and/or statistical aid offered to higher education students, outside of their regular programme of teaching, by parties within the students’ institution specifically assigned to give mathematical and/or statistical support.

A large part of existing MSS research details evaluation, in particular, the impact that MSS has on the students who use it. Comprehensive reviews of various aspects of MSS in higher education appear in Matthews et al. (2013) and Lawson et al. (2020). Matthews et al. (2013) focus on the evaluation and impact of MSS and provide a summary of 56 evaluation studies using predominantly qualitative analysis methods. Lawson et al. (2020) summarise 115 MSS articles in the period 2000–2019 under the headings of users/nonusers, those who work in MSS, and evaluation. Building on Matthews et al. (2013), their evaluation section includes studies from 2013 to 2019. Both reviews highlight the move away from the necessary evaluation conducted by MSS provisions to secure funding to the optimisation of, and difficulties in, MSS evaluation, in addition to studies of both large and small scale indicating the value of MSS. The studies included in these reviews present results such as positive impact on student retention (e.g., O'Sullivan et al., 2014), student confidence (e.g., Dzator & Dzator, 2020), and academic performance (e.g., Jacob & Ní Fhloinn, 2018). This does not mean every MSS provision provides these benefits or indeed sets out to achieve these aims. Formats of MSS across institutions and countries can vary significantly from physical drop-in, appointments, and workshops to bridging courses, asynchronous online resources, and synchronous support via video conferencing — particularly prevalent in the years of pandemic-impacted learning. Research and evaluation methodologies are dependent on how MSS provisions operate, the data gathered by MSS provisions, and what further data can be accessed (Matthews et al., 2013). The broad nature of MSS formats and evaluation methodologies prompted this systematic scoping review to establish how MSS is evaluated, the first review of its kind.

Previous literature reviews (Lawson et al., 2020; Matthews et al., 2013) were UK based with some Irish, Australian, and German (only in Lawson et al., 2020) research also featured. However, MSS is now well established in higher education institutions (HEIs) in the USA (Bhaird and Thomas 2022; Mills et al., 2022), UK (Ahmed et al., 2018; Grove et al., 2019), Ireland (Cronin et al., 2016), Australia (MacGillivray, 2009), Canada (Weatherby et al., 2018), and Germany (Liebendörfer et al., 2017; Schürmann et al., 2021), among other countries. Mills et al. (2022), in their survey of 75 mathematics tutoring centre directors in the USA, found 93.33% of respondents were performing evaluation of their centre; however, they note that published evaluation research in the USA has been sparse. Similarly, Weatherby et al. (2018) found that 88% of 62 English-speaking Canadian universities with mathematics departments had MSS provisions. However, they only reference two Canadian publications that include MSS (Dietsche, 2012; Faridhan et al., 2013). By using the broader definition of MSS outlined earlier and the systematic nature of a scoping review (Tricco et al., 2018), this paper will provide a more detailed picture of MSS evaluation studies published in English worldwide.

Systematic reviews are a defined research approach that provide the strongest evidence according to the hierarchy of evidence pyramid (NSW Government, 2020). This evidence is gathered via a formal process of identifying published empirical studies that fit pre-specified eligibility criteria defined to answer specific research questions. In particular, they feature an explicit, reproducible, predetermined methodology, assessment of the validity of the findings by considering risk of bias, and a synthesis and/or meta-analysis of the results of included studies (Lasserson et al., 2022). There exist different types of systematic reviews; these include systematic (literature) reviews, scoping reviews, rapid reviews, narrative reviews, meta-analysis, and umbrella reviews. The type of systematic review depends on the research question(s) and the nature of the studies to be synthesized. As systematic review results depend on the level of primary studies available, scoping reviews are the appropriate next step in MSS research to establish and summarise the level of research already conducted, building on the two previous literature reviews (Lawson et al., 2020; Matthews et al., 2013). Scoping reviews may examine the extent (that is, size), range (variety), and nature (characteristics) of the evidence on a topic or question, determine the value of undertaking a systematic review, summarise findings from a body of knowledge that is heterogeneous in methods or discipline, or identify gaps in the literature to aid the planning and commissioning of future research (Tricco et al., 2018, p. 1).

This paper presents a scoping review of MSS evaluation literature, meaning broad research questions and inclusion criteria will be used to find and examine relevant studies with a reproducible methodology. This scoping review will explore what data MSS provisions are gathering, how they are analysing that data, and how they use the results of that analysis, with a particular focus on the impact of MSS on students, both users and nonusers. The review aims to use this information to identify areas of future MSS research. The four objectives listed in the review’s protocol (Mullen et al., 2022a) align with the four research questions below, all focused on how MSS is evaluated:

-

(1)

When, where, and how are MSS evaluation studies published?

-

(2)

What are the different formats of MSS evaluated in these studies?

-

(3)

How and what data are collected for MSS evaluation, and is there potential for bias?

-

(4)

What are the analysis methods used in MSS evaluation, and what results have been found?

Sections 2 and 3, detailing the method and results follow, before a concluding discussion about future directions for MSS evaluation research and the role of MSS in mathematics education research more broadly.

2 Method

The review was conducted following the method outlined in the protocol (Mullen et al., 2022a) which was based on the PRISMAFootnote 1 scoping reviews checklist (Tricco et al., 2018). The updated version of this method is presented as minor changes were necessary during the course of the review. The first step, identifying the objectives of the review, has been outlined in the introduction, and the following steps of defining eligibility criteria and information sources, finding and screening of studies, and the data extracted from the included studies will now be outlined. The final step, data synthesis, will be presented in Sect. 3.

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Studies were included using the following criteria: published in English from 1st January 2000, MSS featured had to be in addition to the students’ regular programme of timetabled teaching and be formally organised by MSS providers within a HEI, and evaluation of the impact of MSS on students, whether users and/or nonusers, using either statistical methods or qualitative analysis had to be present. Studies that used only usage statistics for evaluation were excluded. Reports of MSS evaluation at a single institution were excluded to prevent oversaturation; however, reports containing evaluation of multiple MSS provisions (e.g., O'Sullivan et al., 2014) were included. Studies concerning predominantly tutor training, student-tutor interactions, the design of MSS resources or provisions, and grey literature (except relevant reports) were excluded.

2.2 Information sources

In order to ensure broad coverage of MSS literature, which is still in early development, the information sources were varied. To ensure international coverage, the third author contacted colleagues in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the UK, the USA, Germany, and the Netherlands, for relevant sources of national MSS literature and MSS terminology. Subsequently, these sources and terms were used to inform the search strategy. The sources searched included databases, conference proceedings, and national MSS websites. Databases searched were ACM Digital Library, Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest Education Collection (which included PsycINFO, ERIC, and Australian educational database). Conference proceedings searched were as follows:

-

(i)

Congress of the European Society of Research in Mathematics Education (CERME)

-

(ii)

European Society for Engineering Education (SEFI)

-

(iii)

International Congress on Mathematical Education (ICME)

-

(iv)

International Network for Didactic Research in University Mathematics (INDRUM)

-

(v)

Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education (RUME)

-

(vi)

Southern Hemisphere Conference on the Teaching and Learning of Undergraduate Mathematics (Delta)

-

(vii)

International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education (PME)

National MSS/mathematics education websites searched were as follows:

-

(i)

Canadian Mathematics Education Study Group (CMESG)

-

(ii)

Centre for Research, Innovation and Coordination of Mathematics Teaching (MatRIC) — Norwegian centre for excellence in mathematics education

-

(iii)

First Year in Maths (FyiMaths) — Australia and New Zealand-based undergraduate mathematics education network

-

(iv)

Irish Mathematics Learning Support Network (IMLSN)

-

(v)

Math Learning Centre Leaders (MLCL) — USA group of MSS leaders

-

(vi)

Scottish Maths Support Network

-

(vii)

Sigma Network for Excellence in Mathematics and Statistics Support (UK)

Additionally, the UK-based journal MSOR Connections, where MSS literature continues to be published, and the reference lists from the two previous MSS literature reviews, Lawson et al. (2020) and Matthews et al. (2013), were also searched.

2.3 Search strategy

The literature search was limited to publications in English with both quantitative and qualitative studies included. The search was limited to article title, abstract, keywords, and publication titles (dependent on the database). The exact search criteria and search string for each database are available in the supplementary materials. Each search string contained synonyms for higher education (e.g., university, third-level education) and a variety of terms for MSS (e.g., calculus centre, math[ematics] support centre) with binary operators used so that every publication found had higher education and MSS terms. Both British and American English spellings were used.

The first database search took place on March 10, 2022, and the second (to ensure more recent studies had been included in the review) took place on November 9, 2022. In the second search, as PsycINFO was no longer part of the ProQuest Education Collection, it was searched separately.

Conference proceedings, websites, MSOR Connections, and reference lists from Lawson et al. (2020) and Matthews et al. (2013), the “other sources,” were searched from April to June 2022 initially. Then, any newly published conference proceedings or MSOR Connections publications and the websites (for the second time) were searched in November 2022.

2.4 Selection process

Once duplicates were removed, a sample of 100 abstracts from the database search results was screened by all three authors using the inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies between authors’ decisions were discussed with majority ruling. The remaining abstracts were then divided between authors to be screened individually. Other sources were screened by abstract where possible with any duplicate studies found in the database search discounted. Due to the large number of conference proceedings and MSOR Connections articles, studies were first screened by title and then abstract if available. Where no abstract was included, introductory paragraphs of a publication were screened. All pages of websites included in the search were reviewed to find studies that, if present, were screened by abstract.

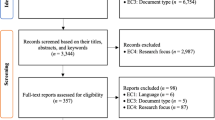

The second round of screening reviewed full publications from both the database and other sources. This began with all authors screening the same three studies, a change from the originally planned five studies due to time constraints. Any discrepancies in inclusion were discussed with the same approach taken as the first round of screening. Subsequently, the remaining publications were divided between authors for individual screening. Reasons for excluding papers in the second round were recorded as part of the summary of the selection process using the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Page et al., 2021) (Fig. 1). The combined number of studies found in both database searches are shown in Fig. 1 per database with the results of the separate PsycINFO search (second search only) in italics. The search process resulted in 136 evaluation studies from 148 publications.

PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., 2021) showing the identification, screening, and inclusion of publications found through databases and other sources

2.5 Data collection process

Owing to the large volume of studies included, the studies were divided into those with an MSS evaluation focus and those where MSS evaluation was not the main focus of the study. The number of data items extracted was reduced for the latter set of studies. The (non-)evaluation focus was based upon studies’ research questions/objectives, their title, and abstract/introduction if the former were not clear. The data extraction process was trialled by all three authors with a pilot form for three publications from each set of studies. The results of this exercise were compared, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The pilot form was updated to reflect these discussions and then used for the remaining studies.

2.6 Data items

The following items were collected from each evaluation-focused study:

-

(i)

Reference details: Title, authors, year of publication, and data source

-

(ii)

Details of institution(s): Name of institution(s) (if given) and country of institution(s)

-

(iii)

MSS format: Student population MSS available and all services provided by MSS provision

-

(iv)

Data collection: How, when, and what type of data were collected, how reliable the data collection method was, and design of data collection (e.g., survey design) if applicable

-

(v)

Methodology: Type of study (qual/quant/mixed methods); whether research questions/aims/objectives were explicit, implied, or not presented; and data analysis method chosen

-

(vi)

Results: Outcomes of study; for example, statistical significance and themes identified

-

(vii)

Nature of research: Funding source and ethics, conducted by MSS practitioners or researchers (internal or external)

“Type of institution,” “location, size and design of MSS centre (if applicable),” and “design of MSS resources, for example bridging courses (if applicable)” were originally listed for collection, but in the process of data extraction, it was found that the type of institution was usually evident from the institution names, and that details of MSS centres and MSS resources design were not informative in understanding the study outcomes collected.

The reference details, details of institution(s), methodology, and results items listed previously were also collected from the non-evaluation-focused studies. The items collected from the non-evaluation-focused studies in the other categories were as follows:

-

(i)

MSS format: A description of the MSS services in the study

-

(ii)

Data collection: How and what type of data was collected

-

(iii)

Nature of research: Ethics, conducted by MSS practitioners or researchers (internal or external)

2.7 Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence

It was planned to evaluate the quality of the methodology and therefore the risk of bias in the studies included in the review using the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 (Hong et al., 2018). However, the first step of the MMAT tool requires explicit research questions, and as will be shown in the results, many included studies did not meet this criterion. As the quality evaluation is an optional part of a scoping review (Tricco et al., 2018), the authors collectively decided to omit this element of the review as it can be done in future systematic literature reviews.

3 Results

Figure 1 shows the full search results, concluding in 148 publications being included in the review, representing 136 MSS evaluation studies (some studies resulted in multiple publications). These were divided into 66 evaluation-focused publications (55 studies) and 82 publications (81 studies) where evaluation was not the main research objective of the publication. This was based on the research questions or aims of the publication where possible, otherwise on the title, abstract, or authors’ reading of the paper. For example, a number of publications focused on the setting up of MSS provisions and provided some initial evaluation of the provision in the publication. In other publications, MSS evaluation was one question of a larger questionnaire or touched on briefly in an interview, and therefore, not the focus of the publications’ results. The list of publications included in the review is available in the supplementary materials.

The following four results subsections answer each research question using the data extracted “per publication” for the first subsection and “per study” for the other three subsections. Where possible, results from all included studies will be presented; however, the evaluation-focused studies will take priority in the reporting of results. Details of each data item collected for the 55 evaluation-focused studies are available in Tables 2 and 3 of the supplementary materials.

3.1 When, where, and how of MSS research publication

The search included all publications from January 1, 2000, to November 9, 2022.Footnote 2 The 148 included publications, 65 journal articles, 31 conference proceedings, 40 MSOR Connections or CETL-MSOR publications (grouped under “MSOR Connections”),Footnote 3 6 theses, and 6 books/reports, graphed in Fig. 2 show the variety of MSS evaluation publications over the past 23 years.

Figure 3 displays the countries in which the included publications were conducted per year. The “multiple” group contains the four publications that were a cross-collaboration from multiple countries, namely, two papers that were a collaboration between Irish and Australian researchers; a paper from an Australian, Irish, and British collaboration; and a report on Irish and Northern Irish MSS. Countries only represented once, namely Canada, Czech Republic, Finland, Italy, Netherlands, Slovakia, and South Africa which has two included publications, are grouped together in Fig. 3 under “other.” Finally, two publications did not identify their country of origin (not stated).

Table 1 presents counts of how explicitly the research questions or aims and ethics details were stated in the 66 evaluation-focused and 82 non-evaluation-focused publications. Funding details were only provided in 10 of the evaluation-focused publications. The authors of the included publications were mainly based in the institution at the focus of their study. Seven evaluation-focused and three non-evaluation-focused publications had exclusively researchers external to the institution, while 14 evaluation-focused and 18 non-evaluation-focused publications were written by a mix of internal and external researchers. Four evaluation-focused and four non-evaluation-focused publications did not provide enough information to determine the status of the researchers.

3.2 MSS formats

The range of MSS formats described in the 136 included studies can be seen in Fig. 4, presented as a heatmap by country group. For example, of the 15 studies conducted in Australia, 9 or 66.67% of the studies featured online resources. Note that 53 studies evaluate more than 1 MSS format.

Popular in the majority of countries, drop-in sessions were the most frequently discussed format of MSS (n = 54). The 18 studies where the MSS was described as an MSC may also involve drop-in support. Appointments, or timetabled one-to-one or small group support, can also be part of a MSC’s services.

Larger group MSS sessions, taking place concurrent with timetabled teaching, fell into two formats: workshops and tutorials. Workshops were usually designed around active learning, while descriptions of MSS tutorials indicated a more teacher or tutor-led class. Bridging courses also involved larger groups of students but generally occurred before timetabled teaching began.

Online communication groups all types of MSS provided through tutors being online either synchronously with students, for example, in a video call, or asynchronously, for example, in discussion boards. This MSS format is increasingly popular since COVID-19 first introduced restrictions on in-person learning. Online resources, where MSS is provided through videos, worksheets, or other materials placed online, have been evaluated more frequently with at least one study per year since 2007 (excluding 2018). Paper resources have also been evaluated throughout the two decades, though to a lesser extent, and often with other types of MSS.

Peer tutoring was identified in only two studies, Maitland and Lemmer (2011) and Parkinson (2009). Both studies feature more experienced undergraduate students tutoring those in need of support and thus are different enough from the other MSS formats to warrant a separate category.

The student population studied was extracted for all the evaluation-focused studies. Note this was not necessarily the same as the population that MSS was available to in the institution(s); for example, first-year students were studied, but second-year students could also access MSS. Notably, 23 of the 55 populations studied were first-year students (42%), highlighting the role of MSS in the transition to higher education. Seven studies focused on students in developmental or foundational mathematics classes, and 10 studies aimed to evaluate MSS for all users. Many publications focused on students from one degree or school with 13 studies researching students studying a form of engineering.

3.3 Data collection

The data source and type of data collected, both of which were categorised, were collected from all studies, while the sample size and data information were extracted from evaluation-focused studies only. Data information, a subjective item as no explicit categories were identified by the authors, recorded what information was (not) provided in the publications with regard to study design and had the potential to bias results. For example, if survey response rates were (not) provided, this was noted under data information.

Seven different data source categories were identified. The most frequent data source was surveys (n = 81). Four of those surveys used adapted versions of previously used questionnaires including (1) the Mathematics Self-efficacy Scale (Betz & Hackett, 1993) in Johnson and O’Keeffe (2016); (2) the Mathematics Self-Efficacy and Anxiety Questionnaire (Deutsch, 2017) in Johnson (2022); (3) the Inventory of Mathematics Attitude, Experience, and Self-Awareness Instrument (Klinger, 2008) and the IMLSN evaluation survey (O'Sullivan et al., 2014) in Carroll (2011) and Carroll and Gill (2012); and (4) the attitude questions from Carroll and Gill (2012) were used in Dzator and Dzator (2020). The second most popular source of data was from institutional or MSS records (n = 74). The other data source categories identified (and the number of studies that used them) were focus groups (n = 8), interviews (n = 15), pre- and post-skills assessments (n = 14), and other (n = 19), which includes various forms of written feedback not gathered through a survey instrument and researchers’ observations or field notes. Nine studies, all non-evaluation focused, did not provide details of their data sources.

Comparing the different MSS formats studied and the data sources used to study them, only the two most popular data sources, surveys, and institutional/MSS records have been used to evaluate every MSS format. Investigating the others, none of the bridging course studies used interviews or focus groups, and only one study involving MSS appointments used a pre- and post-skills assessment as a data source. Table 1 in the supplementary materials presents a full comparison of the MSS formats and data sources. Turning to type of data used for evaluation, Table 2 presents the 14 data types identified, their definition, and the number of studies they were in. There were some formats that did not collect some data types. For example, pre-institutional attainment was not considered when evaluating online communication or tutorials. Broadly, however, the different MSS formats did not collect different data types.

Most evaluation-focused studies had different potential biases or missing information recorded under “data information” which can be read in Table 3 of the supplementary materials. Identifiable trends include a lack of clarity around the source of data, for example, whether it was student reported or from institutional records, unclear sampling strategies used to recruit participants, and a range of different response rates (where they were recorded). Some authors, for example Wilkins (2015), discussed problems and sources of bias with respect to their data collection; others were less explicit.

3.4 Analysis methods and results

The 136 included studies present a wide variety of analysis methods, both quantitative and qualitative, and correspondingly a broad range of results. Table 2 shows the majority of studies had some quantitative data; for example, 95 used quantitative usage data, and thus, most (n = 97) presented some form of descriptive statistics. Some studies did no further analysis, but most quantitative studies presented either hypothesis tests results, correlation analysis, and/or regression analysis. The most frequently presented hypothesis tests were t-tests (n = 22), chi-squared tests (n = 17), and analysis of variance (ANOVA) (n = 13). These were usually used to find the differences between MSS users and non users, or, in some studies, the differences between types of MSS users (usually visit frequency or demographics). Further rigorous analysis connected with these tests, for example, p-value correction for multiple tests and Tukey post hoc test for ANOVA, was not always discussed. Correlation analysis was employed in 15 studies to study the association between MSS use and different measures of student impact, most commonly institution attainment. Simple linear (n = 8), multiple linear (n = 7), and forms of logistic (n = 5) regression were also used in the evaluation of MSS student impact, usually aiming to model institution attainment based on MSS use and in the case of the multivariable models on other factors like pre-institution attainment, diagnostic results, and/or demographics. Byerley et al. (2018) included the most variables (16) in their multinomial logistic regression model, while Offenholley (2014) used 7 variables. The other studies that used regression equations considered between two and five variables. All statistical methods used were frequentist methods as opposed to Bayesian methods.

Qualitative data was collected in 67 of the included studies (the 13 studies with qualitative data from staff also contained qualitative data from students). The most named and used form of analysis was thematic analysis of various forms with 5 of the 14 studies using thematic analysis referencing Braun and Clarke (2006) specifically. Other qualitative analysis methods used were categorisation and general inductive analysis. However, in 34 of all the included studies, no qualitative analysis method was described despite qualitative data and results being presented. Furthermore, 13 of the non-evaluation-focused studies did not describe an analysis method.

The majority of the broad range of results published about MSS evaluation show a positive impact on students, but not all did. Highlights of the 55 evaluation-focused studies include 18 studies finding MSS had a statistically significant positive effect on grades, 15 studies reporting higher pass rates for MSS users, and 13 studies recording a gain in students’ confidence due to MSS. Six studies noted no difference in grades/pass rates between MSS users and nonusers including Offenholley (2014), who compared students from the same course who had access to online MSS and used it, those who did not use it, and those that did not have access, though only a small number used the MSS. Halcrow and Iiams (2011) compared students from the same course who were given 5% of their grade for visiting the MSC weekly versus those who were just told about the MSC and found no difference in grades. Some studies, for example Patel (2011), found statistically significant positive and negative effects of MSS for different cohorts of students. Each study’s results speak to the specific format of MSS in place, the students being studied, and the research design, all presented in Table 3 of the supplementary materials. The results from the other 81 studies that were non-evaluation focused were less specific, although many studies presented forms of student feedback that were generally positive. The helpfulness or usefulness of MSS was usually highlighted in this qualitative data, and similar positive feedback is also highlighted in some of the evaluation-focused studies.

4 Discussion

4.1 When, where, and how of MSS research publication

The inclusion of 148 publications reporting 136 studies from 12 countries in this scoping review shows the geographical spread of MSS and growth of the accompanying evaluation research over the past two decades. Where there is MSS, there is usually evaluation, and while not all evaluation published satisfies the inclusion criteria of this review, the research that does highlights the role MSS plays in institutions. The results of the review revealed MSS evaluation literature exists in more countries than in previously published reviews (Lawson et al., 2020; Matthews et al., 2013), highlighting the advantages of a scoping review. Further publications not included in this review but found through the search strategy show MSS taking place in countries other than those most frequently published. For example, a paper about MSS in Hong Kong (Chan & Lee, 2012) was excluded. It should be highlighted that there could be further countries with MSS publications that were not found owing to this review’s criteria, that is, all publications had to be in English. The issue of underrepresentation of certain geographical areas in mathematics education publications (Di Martino et al., 2023) must also be noted. More reports of how MSS is provided and evaluated in the countries not included or only included in small numbers in the review would be of great interest to the MSS community.

The reason behind extracting the “nature of research” data items was to investigate the way research is conducted which informs the strength of MSS literature. Thus, features of high-quality research (Belcher et al., 2016) reporting such as the statement of research questions and providing ethical details were noted to track the development of MSS literature. These features also affect the suitability of publications for inclusion in systematic reviews as, for example, critical appraisal tools such as the MMAT (Hong et al., 2018), considered for this review, require explicit research questions. Results of this data extraction were somewhat concerning with only 73 (of 148) publications stating research questions or aims and 29 providing ethical information — all publications except one dealt with student data in some capacity. However, as highlighted by the small amount of evaluation literature in the early 2000s, MSS is a relatively nascent research area. The inclusion of publications other than journal articles in this review was purposeful as other publication sources such as conference proceedings may be more accessible for new MSS researchers or staff who provide MSS but do not have research responsibilities. The majority of MSS research is carried out by practitioners immersed in running their institution’s MSS provision (100 publications from internal researchers only). Research may not be a part of their role, or they may not have the funding for it (only 10 of the 66 evaluation-focused publications noted funding). The results of collaborative, funded research has and will develop MSS research. Examples included are Byerly and colleagues who, benefiting from National Science Foundation funding (Mills et al., 2022), authored a series of publications (Byerley et al., 2020; Byerley et al., 2023; Johns et al., 2023) evaluating and comparing 10 USA MSCs with various results. For example, only six of the MSCs had a positive change in grade per one visit based on multiple regression (Byerley et al., 2020). Also, the report from O'Sullivan et al. (2014) provided student-reported results on retention and MSS use on a scale not seen elsewhere. Surveying 1633 students from 9 institutions, 587 of whom had used MSS, they found that 62.7% of 110 students who had both considered leaving higher education and had used MSS were influenced to stay by MSS.

4.2 MSS formats

MSS format trends for countries are confirmed, for example, the case of Germany’s use of bridging courses over other formats. Liebendörfer et al. (2022) explain that German MSS developed owing to a rapid increase in higher education participation rates and subsequent dropout rates, particularly evident in mathematics where insufficient prior knowledge is a factor. Bridging courses, concentrated on reinforcing prior mathematical knowledge, are the primary MSS format in Germany, although other formats in Germany are starting to be evaluated (Liebendörfer et al., 2022). The variety of MSS formats in the UK, Australia, Ireland, and the USA is a result of their respective educational system. In the UK, Lawson and Croft (2021) explain MSS was set up over 25 years ago as a short-term solution to a much larger problem — students entering higher education unprepared for the demands of university mathematics. Owing to a lack of compulsory secondary-level mathematics in the UK and Australia, students may not have studied mathematics or a high level of mathematics in upper secondary school; thus, MSS in a variety of formats was set up in both countries (Lawson & Croft, 2021; MacGillivray, 2009). Interestingly, the same variety of MSS formats is present in Irish studies, though the vast majority of Irish students study mathematics throughout secondary school as a mandatory subject for higher education. However, Irish students’ mathematical attainment is of ongoing concern (Gill et al., 2010; O'Meara et al., 2020); hence, MSS is similarly well-established. The length of time MSS has had to develop aligns with variety in formats. Higher education in the USA lends itself to a variety of MSS formats given the large numbers of HEIs, varying school curricula, and no national curriculum or examinations. Mills et al. (2022) explain that general education courses, including mathematics, are mandatory, and thus, the USA HEIs have a wide array of mathematics students, low pass rates in entry level mathematics courses, and well-established MSS. The small number of longitudinal evaluation studies and other literature about the development of MSS (Ahmed et al., 2018; Croft et al., 2022; Cronin et al., 2016; Grove et al., 2019; MacGillivray, 2009; Mills et al., 2022) point to how established MSS is in the UK, Ireland, Australia, and the USA, and the largely positive evaluation results explain why. For countries with fewer publications, but still positive evaluations, the continued provision of MSS is expected; for example, a recent German-British collaboration notes the current expansion of German MSS (Gilbert et al., 2023).

4.3 Data collection

In many publications, the study design was unclear. Details such as questionnaire design, sampling strategy, and exact sources of records were not presented. Response rates, when provided, were often low, in line with other education research. Finally, the lack of detail in reporting qualitative analysis methods, and in some cases, no methodological details, in publications implies an unsatisfying answer to our third research question. Reasons for this may be less stringent publication rules for most of the sources of MSS evaluation literature or the constraints on the researchers themselves as discussed previously. There are many natural constraints to conducting research on students, and their data, that do affect data collection particularly in MSS research as MSS participation is voluntary; therefore, self-selection effects appear. Studies where quantitative data from existing MSS or institutional records were used usually had clearer data collection strategies. However, they could only consider a small number of variables in examining the impact of MSS; for example, Rylands and Shearman (2018) and Rickard and Mills (2018). On the other hand, studies collecting qualitative data rely on student participation, which is difficult to achieve, especially in an unbiased manner. Wilkins (2015) provided a candid report of the problems with their MSS evaluation study using student surveys. Duranczyk et al. (2006) had fewer issues by adding questions to a larger school-wide survey. Explicit reporting of evaluative issues will allow for greater understanding and comparison of results, which is necessary for systematic reviews. As outlined in Sect. 1, systematic reviews provide the highest level of evidence (NSW Government, 2020) and would be an important development in MSS research.

4.4 Analysis methods and results

The variation in analysis methods and results in MSS evaluation research is the outcome of many researchers in a relatively new research area evaluating their own unique MSS provisions. Based on the lack of funding disclosed, MSS research resources are sparse. There are many challenges to MSS evaluation, in particular, the issue of self-selection bias and how to demonstrate causal relationships. Developments in evaluation research include use of statistical methods to analyse associations between grades and MSS usage moving from chi-squared tests and similar (e.g., Mac An Bhaird et al., 2009) to building regression models involving MSS variables (e.g., Byerley et al., 2018). Byerley et al. (2018) consider the issues of self-selection bias and causation versus correlation and point out studies demonstrating causal relationships require random assignment to the treatment condition, which is often not possible or ethical with MSS. Instead, self-selected users and nonusers are compared. As noted in the results, Offenholley (2014) gave 8 of 112 sections of elementary Algebra students access to online MSS and compared the results of users, nonusers, and those without access, finding MSS had no impact on grades, but there was low MSS uptake. Studies like these may be more possible within the USA higher education system where one course is taught across many sections, though it would be difficult to evaluate MSCs in this way. However, in other higher educational systems, like Ireland, students are separated into mathematical courses by degree and usually taught as one class. Providing access to MSS for some students and not others in one class could be considered unethical. Thus, the issue of self-selection bias affects the results of almost all studies included in this review.

The diversity in answers to the second, third, and fourth research questions, namely 10 formats of MSS, 7 data sources, 14 data types, over 40 analysis methods, and corresponding results all from 136 studies, is extensive. This scoping review presents a broad overview of MSS evaluation research published in English worldwide with the objective of establishing how MSS researchers are investigating the impact of MSS on students and what that impact is. While it is possible to extrapolate the positive impacts of MSS, particularly on students’ grades, it is impossible to reach definitive conclusions about this impact due to lack of uniformity and robustness in data collection and analysis. This is not unexpected due to the many factors impacting MSS research previously discussed but does indicate further development of MSS evaluation research is desirable. The scoping review definition previously presented suggests a review can “summarise findings from a body of knowledge that is heterogeneous in methods or discipline” (Tricco et al., 2018, p. 1). Given there are no standard methodologies or research metrics yet established in the discipline of MSS learning impact, we see from our results that the lack of heterogeneity in methodologies used make it difficult to compare and contrast studies about purported effect of MSS. We do, however, see a trend in MSS literature evolving from scholarship in the early years to more rigorous research in recent years, and this is very welcome.

5 Future directions for MSS evaluation research

Development of more rigorous study design is a necessary next step in MSS evaluation. Self-selection bias, particularly when research relies on student-reported data, must be considered and addressed whenever evaluating MSS. Finding a causal link between MSS and aspects of students’ mathematical experiences is still a work in progress due to evaluation methods used thus far not fully incorporating self-selection bias. Herzog (2014), included in this review, aimed to demonstrate propensity score matching, which incorporates self-selection bias, with a MSC evaluation as an example case study, and found positive results, yet this method was not used again until Büchele and Schürmann (2023). Büchele and Schürmann (2023), using propensity score matching and difference-in-differences methods which control for students’ self-selection, have taken a step forward in this area. However, as they admit, there is a need for further development and an increase in study scale of this type of evaluation as they only studied a course-specific MSC open one afternoon a week. Hopefully, this review will bring greater awareness and use of these methods to benefit MSS evaluation research. Other elements of study design, for example, ensuring representative responses to surveys and well-considered missing data strategies, could also be developed further. Who is and is not using MSS and who is and is not participating in MSS evaluation research must both be considered to inform rigorous evaluation research.

The findings of this review also highlight how MSS evaluation may be studied further. More multi-institutional and international collaborations would be welcome as only 16 multi-institutional studies and 3 international collaborations were found in this review, yet they contained noteworthy results. There are rich opportunities for collaboration in MSS research between not only MSS practitioners but also mathematics education researchers, statisticians, methodological researchers, and those who provide STEM education at university. Collaboration across various support services available in HEIs would also be welcome as students do not necessarily access these services in isolation. One approach to furthering MSS collaboration and data collection would be by using the same instrument in multiple institutions much like how Dzator and Dzator (2020) used items from Carroll and Gill’s (2012) research instrument. Validation of survey instruments (e.g., exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis) built for general mathematics education research (e.g., mathematics anxiety scales) in MSS settings would also be valuable to the MSS research community. As discussed in Howard et al. (2023), another approach for furthering collaboration, and MSS research more generally, would be to have standardised terminology for MSS that is internationally used. We recommend all future MSS research includes the key terms “mathematics and statistics support” and “higher education”.

Systematic reviews with more stringent eligibility criteria and specific research questions about aspects of MSS are a credible next step in combining MSS research for greater generalisation of results. This review indicates drop-in MSS, which featured in 54 studies, would be the most viable format of MSS to examine via a systematic review and/or meta-analysis as such reviews benefit from a greater number of studies. Additionally, meta-analysis would require similar populations and outcome measures to have been used in the included studies. In general, while a statistical comparison of MSS evaluation results would advance the field without the need for further resource-heavy data collection, the results of this review indicate that this process may be hindered by missing reporting features. Also, changes in students’ MSS usage patterns during and after the pandemic (Gilbert et al., 2023; Johns & Mills, 2021; Mullen et al., 2022b, 2023) must be accounted for. Further publications of evaluations of drop-in MSS and (or versus) other MSS formats post-pandemic would improve the relevance of results of a systematic review of MSS evaluation.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, this scoping review highlights the variety of MSS evaluation work already published and the great potential for more work in this area. The research included in this review indicates the positive impact MSS can have on students but also the need for more rigorous methodological evaluation of this effect. There is a large international group of MSS researchers and practitioners who can build a comprehensive research agenda around MSS evaluation and other important aspects of MSS research. Greater understanding of students’ higher education mathematics experience is needed to continue attempts at solving the “mathematics problem,” and MSS research and evaluation are key pieces of the puzzle.

Data availability

The data in this paper are from publications, the full list of which are available in the supplementary materials.

Notes

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses.

The year of publication for all references was updated during the writing of this paper to reflect the publications’ official references. Subsequently, the publication by Johns et al. (2023), while available since 2021 online and thereby found in the search, falls outside the official search years.

As later CETL-MSOR proceedings were published as MSOR Connections special issues, CETL-MSOR proceeding papers are grouped with MSOR Connections papers instead of the other conference proceedings papers.

References

Ahmed, S., Davidson, P., Durkacz, K., Macdonald, C., Richard, M., & Walker, A. (2018). The provision of mathematics and statistics support in Scottish higher education institutions (2017) – A comparative study by the Scottish mathematics support network. MSOR Connections, 16(3), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.21100/msor.v16i3.798

Alcock, L., Hodds, M., Roy, S., & Inglis, M. (2015). Investigating and improving undergraduate proof comprehension. Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 62(7), 742–752. https://doi.org/10.1090/noti1263

Belcher, B. M., Rasmussen, K. E., Kemshaw, M. R., & Zornes, D. A. (2016). Defining and assessing research quality in a transdisciplinary context. Research Evaluation, 25(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv025

Betz, N.E. and Hackett, G. (1993). Mathematics self-efficacy scale manual, instrument and scoring guide. Mind Garden

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Büchele, S., & Schürmann, M. (2023). Causal evidence of the effect of a course specific mathematical learning and support center on economics students’ performance and affective variables. Studies in Higher Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2271029

Byerley, C., Campbell, T., & Rickard, B. (2018). Evaluation of impact of calculus center on student achievement. In A. Weinburg, C. Rasmussen, J. Rabin, M. Wawro, & S. Brown (Eds.), Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference on Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education (pp. 816–825). The Special Interest Group of the Mathematical Association of America (SIGMAA) for Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education.

Byerley, C., James, C., Moore-Russo, D., Rickard, B., Mills, M., Heasom, W., Oien, J., Farthing, C., Burks, L., Ferreira, M., Mammo, B., & Moritz, D. (2020). Characteristics and evaluation of ten tutoring centers. In S. Karunakaran, Z. Reed & A. Higgins (Eds.), Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference on Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education (pp. 70–78). The Special Interest Group of the Mathematical Association of America (SIGMAA) for Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education.

Byerley, C., Johns, C., Moore-Russo, D., Rickard, B., James, C., Mills, M., Mammo, B., Oien, J., Burks, L., Heasom, W., Ferreira, M., Farthing, C., & Moritz, D. (2023). Towards research-based organizational structures in mathematics tutoring centres. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 43(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrac026

Carroll, C. (2011). Evaluation of the University of Limerick Mathematics Learning Centre [BSc dissertation, University of Limerick]. https://mathcentre.ac.uk/resources/uploaded/evalmaths-l-centrelimerickcarrollgillpdf.pdf(mathcentre.ac.uk)

Carroll, C., & Gill, O. (2012). An innovative approach to evaluating the University of Limerick’s Mathematics Learning Centre. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 31(4), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrs008

Chan, L., & Lee, J. (2012). Learning support in mathematics and statistics: Mathematics learning centre. In L. Gónez Chova, I. Candel Torres, & A. López Martínez (Eds.), EDULEARN12 Proceedings: 4th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies (pp. 926–933). International Association of Technology, Education and Development (IATED).

Croft, T., Grove, M., & Lawson, D. (2022). The importance of mathematics and statistics support in English universities: An analysis of institutionally-written regulatory documents. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 44(3), 240–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2021.2024639

Cronin, A., Cole, J., Clancy, M., Breen, C., & Ó’Sé, D. (2016). An audit of mathematics learning support provision on the island of Ireland in 2015. National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education

Deutsch, M. (2017). The effect of project-based learning on student self-efficacy in a developmental mathematics course [Doctoral dissertation, Edgewood College]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Di Martino, P., Gregorio, F., & Iannone, P. (2023). The transition from school to university in mathematics education research: New trends and ideas from a systematic literature review. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 113(1), 7–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-022-10194-w

Dietsche, P. (2012). Use of campus support services by Ontario college students. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 42(3), 65–92. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v42i3.2098

Duranczyk, I. M., Goff, E., & Opitz, D. L. (2006). Students’ experiences in learning centers: Socioeconomic factors, grades, and perceptions of the math center. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 36(2), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2006.10850186

Dzator, M., & Dzator, J. (2020). The impact of mathematics and statistics support at the academic learning centre, Central Queensland University. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 39(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hry016

Faridhan, Y. E., Loch, B., & Walker, L. (2013). Improving retention in first-year mathematics using learning analytics. In H. Carter, M. Gosper, & J. Hedberg (Eds.), Electric Dreams: Proceedings of the 30th ASCILITE-Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education Annual Conference (pp. 278–282). Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education.

Gill, O., O’Donoghue, J., Faulkener, F., & Hannigan, A. (2010). Trends in performance of science and technology students (1997–2008) in Ireland. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 41(3), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207390903477426

Gilbert, H. J., Schürmann, M., Lawson, D., Liebendörfer, M., & Hodds, M. (2023). Post-pandemic online mathematics and statistics support: Practitioners’ opinions in Germany and Great Britain & Ireland. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2023.2184282

Grove, M., Croft, T., & Lawson, D. (2019). The extent and uptake of mathematics support in higher education: Results from the 2018 survey. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 39(2), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrz009

Gueudet, G. (2008). Investigating the secondary–tertiary transition. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 67, 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-007-9100-6

Hawkes, T., & Savage, M. D. (2000). Measuring the mathematics problem. The Engineering Council. http://www.engc.org.uk/engcdocuments/internet/Website/Measuring%20the%20Mathematic%20Problems.pdf

Halcrow, C., & Iiams, M. (2011). You can build it, but will they come? Primus, 21(4), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511970903164148

Herzog, S. (2014). The propensity score analytical framework: An overview and institutional research example. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2014(161), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.20065

Hochmuth, R., Broley, L., & Nardi, E. (2021). Transitions to, across and beyond university. In V. Durand-Guerrier, R. Hochmuth, E. Nardi, & C. Winsløw (Eds.), Research and development in university mathematics education (pp. 193–215). Routledge.

Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M. C., & Vedel, I. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

Howard, E., Mullen, C., & Cronin, A. (2023). A scoping systematic review of mathematics and statistics support evaluation literature: Lessons learnt. In A. Twohill and S. Quirke (Eds.) Proceedings of the Ninth Conference on Research in Mathematics Education in Ireland (pp. 69-73). Dublin City University. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10062919

Jacob, M., & Ní Fhloinn, E. (2018). A quantitative, longitudinal analysis of the impact of mathematics support in an Irish university. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 38(4), 216–229. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hry012

Johns, C., & Mills, M. (2021). Online mathematics tutoring during the COVID-19 pandemic: Recommendations for best practices. Primus, 31(1), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511970.2020.1818336

Johns, C., Byerley, C., Moore-Russo, D., Rickard, B., Oien, J., Burks, L., James, C., Mills, M., Heasom, W., Ferreira, M., & Mammo, B. (2023). Performance assessment for mathematics tutoring centres. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 42(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrab032

Johnson, H. A. (2022). Mathematics learning support center visits and college students’ mathematics anxiety and self-efficacy [Doctoral dissertation, University of West Florida]. Proquest Information and Learning. http://gateway.proquest.com.ucd.idm.oclc.org/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&res_dat=xri:pqm&rft_dat=xri:pqdiss:28722285

Johnson, P., & O’Keeffe, L. (2016). The effect of a pre-university mathematics bridging course on adult learners’ self-efficacy and retention rates in STEM subjects. Irish Educational Studies, 35(3), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2016.1192481

Klinger, C. M. (2008). On mathematics attitudes, self-efficacy beliefs, and math-anxiety in commencing undergraduate students. In V. Seabright & I. Seabright. (Eds.), Crossing Borders-Research, Reflection and Practice in Adults Learning Mathematics. Proceedings of the 13th international conference on Adults Learning Mathematics (pp. 88–97). Adults learning mathematics (ALM) – A research forum.

Lasserson, T. J., Thomas, J., & Higgins, J. P. T., (2022). Chapter 1: Starting a review. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Lawson, D., Croft, A. C., & Halpin, M. (2003). Good practice in the provision of mathematics support centres. LTSN Maths, Stats & OR Network. https://mathcentre.ac.uk/resources/Good%20Practice%20Guide/goodpractice2E.pdf

Lawson, D., & Croft, A. C. (2021). Lessons for mathematics higher education from 25 years of mathematics support. In V. Durand-Guerrier, R. Hochmuth, E. Nardi, & C. Winsløw (Eds.), Research and development in university mathematics education (pp. 22–40). Routledge.

Lawson, D., Grove, M., & Croft, T. (2020). The evolution of mathematics support: A literature review. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 51(8), 1224–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739x.2019.1662120

Liebendörfer, M., Hochmuth, R., Biehler, R., Schaper, N., Kulinski, C., Khellaf, S., Colberg, C., Schürmann, M., & Rothe, L. (2017). A framework for goal dimensions of mathematics learning support in universities. In T. Dooley, & G. Gueudet. (Eds.), Proceedings of the Tenth Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education (CERME10) (pp. 2177–2184). DCU Institute of Education and ERME.

Liebendörfer, M., Büdenbender-Kuklinski, C., Lankeit, E., Schürmann, M., Biehler, R., & Schaper, N. (2022). Framing goals of mathematics support measures. In Biehler, R., Liebendörfer, M., Gueudet, G., Rasmussen, C., Winsløw, C. (Eds.), Practice-oriented research in tertiary mathematics education. Advances in mathematics education. (pp. 91–120) Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14175-1_5

Mac an Bhaird, C., & Thomas, D. A. (2022). A survey of mathematics learning support in the United States. Teaching Mathematics and its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 42(3), 249–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrac017

Mac an Bhaird, C., Morgan, T., & O'Shea, A. (2009). The impact of the mathematics support centre on the grades of first year students at the National University of Ireland Maynooth. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 28(3), 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrp014

MacGillivray, H. (2009). Learning support and students studying mathematics and statistics. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 40(4), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207390802632980

Maitland, I., & Lemmer, E. (2011). Meeting the social and emotional needs of first-year mathematics students through peer-tutoring. Acta Academica, 43(4), 127–151. https://journals.ufs.ac.za/index.php/aa/article/view/1333.

Matthews, J., Croft, T., Waller, D., & Lawson, D. (2013). Evaluation of mathematics support centres: A literature review. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications, 32(4), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrt013

Mills, M., Rickard, B., & Guest, B. (2022). Survey of mathematics tutoring centres in the USA. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 53(4), 948–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2020.1798525

Mullen, C., Cronin, A., Pettigrew, J., Shearman, D., & Rylands, L. (2023). Optimising the blend of in-person and online mathematics support: The student perspective. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2023.2226153

Mullen, C., Howard, E., & Cronin, A. (2022a). Protocol: A scoping literature review of the impact and evaluation of mathematics and statistics support in higher education. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2SP7M

Mullen, C., Pettigrew, J., Cronin, A., Rylands, L., & Shearman, D. (2022b). The rapid move to online support: Changes in pedagogy and social interaction. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 53(1), 64–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2021.1962555

NSW Government. (2020, August). What is an evidence hierarchy? https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/789163/What-is-an-Evidence-Hierarchy.pdf

Offenholley, K. H. (2014). Online tutoring research study for remedial algebra. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 38(9), 842–849. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2013.803941

O’Meara, N., Prendergast, M., & Treacy, P. (2020). What’s the point? Impact of Ireland’s bonus points initiative on student profile in mathematics classrooms. Issues in Educational Research, 30(4), 1418–1441. http://hdl.handle.net/10344/9663.

O'Sullivan, C., Mac an Bhaird, C., Fitzmaurice, O., & Ní Fhloinn, E. (2014). An Irish Mathematics Learning Support Network (IMLSN) report on student evaluation of mathematics learning support: Insights from a large scale multi‐institutional survey. Limerick: National Centre for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching and Learning. http://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/6890/1/CMAB_IMLSNFinalReport.pdf

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Parkinson, M. (2009). The effect of peer assisted learning support (PALS) on performance in mathematics and chemistry. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(4), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290903301784

Patel, C. (2011). Approaches to studying and the effects of mathematics support on mathematical performance [Doctoral dissertation, Coventry University]. https://pureportal.coventry.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/approaches-to-studying-and-the-effects-of-mathematics-support-on-

Rickard, B., & Mills, M. (2018). The effect of attending tutoring on course grades in Calculus I. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 49(3), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739x.2017.1367043

Rylands, L. J., & Shearman, D. (2018). Mathematics learning support and engagement in first year engineering. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 49(8), 1133–1147. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739x.2018.1447699

Schürmann, M., Gildehaus, L., Liebendörfer, M., Schaper, N., Biehler, R., Hochmuth, R., Kuklinski, C., & Lankeit, C. (2021). Mathematics learning support centres in Germany – An overview. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 40(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hraa007

Thomas, M. O. J., de Freitas Druck, I., Huillet, D., Ju, M. K., Nardi, E., Rasmussen, C., & Xie, J. (2015). Survey Team 4: Key mathematical concepts in the transition from secondary to university. In Cho, S. (Ed), The Proceedings of the 12th International Congress on Mathematical Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12688-3_18

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garitty, C., … S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Weatherby, C., Kotsopoulos, D., Woolford, D., & Khattak, L. (2018). A cross-sectional analysis of mathematics education practices at Canadian universities. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 12(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v12i1.5099

Wilkins, L. (2015). Maybe we could just count the boxes of chocolates? Measuring the impact of learning development mathematics support for undergraduate students. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 9(2), A91-A115. https://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/view/366

Acknowledgements

To be true to the nature of a systematic literature review of this kind, it involved a lot of archival work. Many proceedings were hosted on now defunct web links, and so local copies needed to be sourced. We would therefore like to thank the following colleagues for their generosity of time and spirit in sourcing these manuscripts. In particular, thank you to Alejandro Gonzales Martin, Gisele Kaiser, Jane Butterfield, Miroslav Lovric, and Veselin Jungic (Canada, CERME and ICME); Birgit Loch and Donald Shearman (Australia); Carolyn Johns and Melissa Mills (USA); Tracy Craig and Anita Cambell (Netherlands and South Africa); Tanya Evans and Mike Thomas (New Zealand); Marketa Matulova, Zuzana Pátíková, and Josef Rebenda (Czech Republic); Tim Fukawa-Connelly, Shiv Karunakaran, Chris Rasmussen, and Aaron Weinberg (RUME); David Bowers (MSOR Connections); Emma Cliffe, Duncan Lawson, and Rob Wilson (Sigma); and Burkhard Alpers, Klara Ferdova, and Mike Murphy (SEFI).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the development of the objectives, the selection criteria, the search strategy, and the data extraction criteria of the review. Anthony Cronin, as the discipline expert, led the identification of databases and other sources to search for publications. All authors conducted the literature search with Emma Howard, as the methodological expert, leading the database search. The screening process and data extraction were conducted by all three authors with Claire Mullen reviewing the majority of publications in each stage. Claire Mullen led the results, analysis, and synthesis. The manuscript was written by Claire Mullen with the other authors providing feedback. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The review will form part of Claire Mullen’s PhD thesis which is in preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mullen, C., Howard, E. & Cronin, A. A scoping literature review of the impact and evaluation of mathematics and statistics support in higher education. Educ Stud Math (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-024-10332-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-024-10332-6