Abstract

Mexico City is one of the most polluted cities in the world, and one in which air contamination is considered a public health threat. Numerous studies have related high concentrations of particulate matter and ozone to several respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and a higher human mortality risk. However, almost all of those studies have focused on human health outcomes, and the effects of anthropogenic air pollution on wildlife species is still poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the impacts of air pollution in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area (MCMA) on house sparrows (Passer domesticus). We assessed two physiological responses commonly used as biomarkers: stress response (the corticosterone concentration in feathers), and constitutive innate immune response (the concentration of both natural antibodies and lytic complement proteins), which are non-invasive techniques. We found a negative relationship between the ozone concentration and the natural antibodies response (p = 0.003). However, no relationship was found between the ozone concentration and the stress response or the complement system activity (p > 0.05). These results suggest that ozone concentrations in air pollution within MCMA may constrain the natural antibody response in the immune system of house sparrows. Our study shows, for the first time, the potential impact of ozone pollution on a wild species in the MCMA presenting the Nabs activity and the house sparrow as suitable indicators to assess the effect of air contamination on the songbirds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atmospheric pollution directly affects the health of human and wildlife species living in urbanized areas (review in Manisalidis et al. 2020). The negative effects of air pollution are more noticeable in megacities (metropolitan areas with a total population over ten million), where the emissions of atmospheric contaminants can be unprecedented in severity and extent (Molina and Molina, 2004). This is the case in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area (MCMA), which consists of Mexico City and its peri-urban area. The MCMA has a human population of more than 20 million, more than 5 million vehicles, and about 78,000 industrial buildings CONAPO, (2012). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Mexico City was considered the most contaminated place in the world at the end of the 20th century, mainly due to a high number of toxic fuel vehicles and high industry activity (WHO, 1997). Following this report, several mitigating measures have been taken (including the creation of Mexico City´s environmental atmospheric monitoring agency), which have substantially reduced pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon monoxide (CO), and sulfur dioxide (SO2). However, over the last two decades, both ozone (O3) and PM10 (particulate matter) still currently exceed the Mexican environmental standard guidelines (SEDEMA, 2016). The high levels of PM10 and O3 are considered a public health threat in Mexico City. Several studies conducted in MCMA have shown a positive relationship between the high concentrations of PM10 and O3, and human mortality risk (Carbajal-Arroyo, et al. 2010; Romieu et al., 2012; Riojas-Rodriguez et al., 2014). MCMA residents are highly exposed to air pollution, and have been found to show signs of an early brain imbalance in genes involved in innate and adaptive immune responses (Calderón-Garcidueñas et al., 2012). Furthermore, Calderón-Garcidueñas et al. (2015) warned of the inflammatory effect of PM10 and O3 concentrations on the central nervous system in clinically healthy children living in the MCMA. Different studies on human health outcomes in other polluted locations have also found that ozone plays an important role as an inflammatory factor in airway diseases (Hiltermann et al.,1998, Schwela, 2000, Alexis et al., 2010, Oakes et al., 2013). Several studies have also shown a positive relationship between ozone concentration and levels of stress hormones in humans (Miller et al., 2016, Rajagopalan and Brook, 2016, Wang et al., 2022, Xia et al., 2022). Regardless of the concern about the potentially harmful effects of these and other air pollutants on human health outcomes (Héroux et al., 2015; Mannucc et al., 2015), knowledge of their consequences on wild animals is scarce, and most of the limited available evidence comes from birds. As in humans, some negative effects of pollutants have been found in wildlife (e.g Schilderman et al., 1997 for negative effects of heavy metals on DNA oxidative damage in pigeons; Gorriz et al. 1994 for negative effects of coal-fired power plants in the tracheal epithelium of passerine birds and small mammals; Herrera-Dueñas et al. 2014 for a comparison of oxidative damage in house sparrows between two zones differing in their pollution levels; Cruz-Martinez et al., 2015 for negative effects of industry pollutants on the immune response of tree swallows; North et al. 2017 for a relationship between traffic pollutants and morphology, immunity and oxidative stress in european starlings; Sanderfoot and Holloway 2017 for a review of adverse health impacts of different air pollutants on various bird species). For these reasons, birds have been used as a model species to evaluate the effect of atmospheric pollution on urban animal species, as they have been shown to be effective bioindicators due to their wide distribution, high sensitivity to pollutants, and their important role in urban ecosystem services (Furness, 1993; Brown et al., 1997; Swaileh and Sansur, 2006; Kekkonen et al., 2012).

Air pollution can cause stress and health problems to birds by activating different physiological processes, such as oxidative damage (Isaksson et al., 2017, Salmón et al., 2018), shortening telomeres (Salmón et al., 2016), and mobilization of heavy metals to feathers as a detoxification process (Chatelain et al. 2014). Pollutants can act as stressors by triggering a stress response, an evolved suite of physiological, hormonal, and behavioral responses which are exhibited and conserved across many vertebrate taxa (Wingfield and Ramenofsky, 1999; Romero, 2004). One of these responses in birds is secretion of the glucocorticoid corticosterone (Holmes and Phillips, 1976). The release of corticosterone is adaptive for birds in the short-term, as it facilitates survival of life-threatening challenges by elevating glucocorticoids to mobilize energy stores (Sapolsky et al., 2000), activating escape behavior (Wingfield and Romero, 2001), and diverting energy to self-maintenance via changes in behavior and physiology (Wingfield and Sapolsky, 2003). However, chronically elevated levels of this hormone have negative consequences to cognitive ability, growth, body condition and immune defense (Wingfield and Ramenofsky, 1999; Sapolsky et al., 2000). Besides the effects of glucocorticoids on immune responses, the immune system can also be directly affected by exposure to air pollutants. For example, solid particles and high rates of nitrogen oxides from the polluted air can cause a marked decrease in the number of pulmonary surfactant precursors, reducing the innate protection mechanisms of the lung, as has been reported for pigeons (Columba livia) living in the city of Madrid, Spain (Lorz and Lopez, 1997). Nestlings of tree swallows (Tachycineta bicolor) growing in air-polluted sites showed a reduction of the T cell response to the phytohemagglutinin skin test (Cruz-Martinez et al., 2015).

The high air pollution in MCMA could be affecting the health of the wild birds living there, however, there are no studies addressing this topic as all research to date has been focused on humans. For this reason, we evaluated the potential relationship between the concentration of air pollutants and two physiologic traits of the house sparrows: (1) stress (corticosterone concentration in feathers), and (2) constitutive innate immune response (concentration of both natural antibodies and lytic complement proteins). To achieve this, we used the natural air pollution gradient that exists in the MCMA. We predicted that both physiological responses would be decreased at sites with higher air pollution. Because other anthropogenic factors related to urbanization could be negatively affecting the physiology of birds, we also considered human population density, densities of houses and industrial complexes, as well as urban land-use at each of our sampling sites.

Material and methods

Study species

House sparrows are one of the world’s most broadly distributed species. They were introduced to North America in the 1850s from Europe and rapidly expanded to cover all of the United States and most of Canada and Mexico by the early 1900s (Grinnell, 1919). This species is closely associated with human activity and is highly abundant in urban landscapes. Several studies have shown that this species is sensitive to different stressors associated with urbanization level, which makes it a useful bioindicator. Individuals of this species have shown deficiencies in body condition (Liker et al., 2008; Bókony et al., 2010; Meillère et al., 2015), antioxidant capacity (Herrera-Dueñas et al., 2014), or feather quality (Meillère et al., 2017) in more urbanized habitats. This species also bioaccumulates persistent organic pollutants (Nossen et al., 2016) and heavy metals (Pinowski et al., 1994; Kekkonen et al., 2012; Millaku et al., 2014).

Area characterization and measurements of air pollution

The MCMA is located on a high plateau more than 2000 m above sea level in the central part of Mexico. The MCMA consists of Mexico City, 59 municipalities of the State of Mexico, and 1 municipality from the State of Hidalgo. The MCMA has high concentrations of air pollutants, and because of its high altitude and low latitude, it receives relatively strong ultraviolet radiation that promotes photochemical reactions which generate O3 from precursor substances such as NOx (Benítez-García et al., 2015).

Mexico City has an Air Quality Monitoring Network with a total of 32 automated stations for criteria gases and PM in MCMA. Monitoring data are transferred daily and hourly to an open access inventory (http://www.aire.cdmx.gob.mx). We selected 6 study sites from nearby these 32 stations to create a gradient of air pollution: Tlanepantla (TLA): 19°31′44.677′′N, 99°12′16.549′′O; Vallejo (VAL): 19°29′3.552′′N, 99°8'44.77′′O; Pedregal (PED): 19°19′30.526′′N, 99°12′14.889′′O; Cantera-Oriente Pedregal (COP): 19°19′12.565′′, 99°10'25.172′′O; UAM-Iztapalapa (UAM): 19°21′38.858′′N, 99°4′25.968′′O; and Tlahuac (TLH): 19°14′47.252′′N, 99°0′38.03′′O (Fig. 1). Four study sites are located within an automated station, and VAL and COP were located nearby stations (less than 4 km). The data for VAL was obtained from the Camarones station and the data for COP were from the Pedregal station. The atmospheric pollutants considered for our study were: PM10, O3, SO2, CO, and NOx. We used the mean concentrations of each pollutant from 1 August 2013 to 31 May 2014 to determine our six sampling zones. This period includes the molting period of house sparrows, which occurs between August-September (personal observation JS), and the period in which immune response was assessed for each individual. In preliminary analyses, we also calculated the mean concentrations of each pollutant recorded during the molting period of sparrows (August and September 2013) for CORT analysis, and pollutants recorded during captures (the mean pollution record a month before each bird sampling) for the immunological analysis (February, March, and April 2014 depending on the capture of each individual). The results obtained with these mean concentrations showed similar relationships between study variables (data not shown). Given the particular climatic and topographic conditions of the city that may promote daytime variations in pollutants measurements, we think that analyzing a period of time from molt to sampling provides a more robust and representative measurement of the degree of pollution in each sampling zone, which can simultaneously relate to both physiological responses (stress and immune).

To conduct a better characterization of each of our study sites, and in order to understand the role of other anthropogenic variables that could also influence the physiology of the birds, we recorded the following variables at each site: Human population density (number of inhabitants/km2), housing density (number of houses/km2), industry density (number of industrial complexes/km2), and land-use (percentage of urban, agricultural and forest land). We obtained this information from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography of Mexico (INEGI: http://www.inegi.org.mx/) for each one of the municipalities where our study sites were located.

Field sample collections

We captured house sparrows from March to May of 2014 (77 house sparrows; 33 males, and 44 females. Table 2) using mist nets. After sampling, the birds were released. All individuals were weighed using a digital balance (sensitivity 0.01 g), and the tarsus length was measured to the nearest 0.1 mm using a digital caliper. Body condition was quantified by sex as body mass relative to structural body size (tarsus length) by calculating the scaled mass index following Peig and Green (2010). We collected blood samples (150–200 μl) taken from the jugular vein. These were collected with heparinized syringes and kept chilled. On the day of collection, blood samples were centrifuged at 7000 g for 20 min to obtain plasma, which was frozen at −20 °C until physiological analysis.

Stress response

Stress response was measured as the amount of corticosterone (CORT) deposited in the feathers, which provides a historical record of an individual’s hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activity during the period of feather growth (Bortolotti et al., 2008). We collected the first rectrice from 70 individuals (31 males and 39 females). Feather corticosterone was determined using the method described by Bortolotti et al. (2008). The concentration of corticosterone in the feather extracts was measured with a radioimmunoassay using standard methods (see Blas et al. 2005). Feather corticosterone levels are expressed as a function of feather length (pg/mm). We validated this method for the recovery of exogenous CORT in house sparrow feathers by adding exogenous CORT to a pool of feather extracts and obtained a recovery rate of 92% (see Bortolotti et al. 2008 for details). Two types of results showed that our assays were suitable to represent stress levels: (1) feathers extracts in relation to the CORT standard curve showed similar slopes (CORT; F3,12 = 0.233; p = 0.329), and (2) the successful recovery of exogenous CORT added to control samples. We measured samples in three separate assays, with intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 3.72 and 2.30%.

Innate immunity

Immunity was assessed following the assay described by Matson et al. (2005). This methodology allows for the simultaneous measurement of two constitutive innate immune functions: the hemagglutination reaction between natural antibodies and antigens (hereafter hemagglutination), and the hemolysis reaction of exogenous erythrocytes, which is a function of the number of lytic complement proteins present in the sampled blood (hereafter hemolysis). This is a non-invasive technique that requires a small volume of blood, does not involve the recapture of individuals, and is considered to be an integrative method to assess immunity (Matson et al., 2005; Palacios et al., 2012). Different studies have used this method to assess the costs and fitness consequences of immune responses (Møller and Haussy, 2007; Parejo and Silva, 2009; Nebel et al., 2012), to analyze immune responses under different ecological contexts, like a metal pollution gradient (Vermeulen et al. 2015), or under environmental heterogeneity (Pigeon et al., 2013), and to obtain an indicator of the study organisms’ health status (Deem et al., 2011).

The assay was conducted in 96-well round bottom assay plates (Corning Costar #3795). Twenty-five microliters of eight plasma samples were pipetted into columns 1 and 2 of the plate, and 25 µl of 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma #P3813, St Louis, MO) were added to columns 2–12. Using a multi-channel pipette, the contents of the column 2 wells were serially diluted (1:2) through column 11, resulting in dilutions ranging from 1 to 1/1024, with a total volume of 25 µl in every well. The 25 µl of PBS only in column 12 served as a negative control. For the assay itself, 25 µl of a 1% rabbit blood cell (HemoStats laboratories Dixon, CA, USA) suspension was added to all wells, effectively halving all plasma dilutions. Each plate was then sealed and gently vortexed for 10 s prior to incubation, during which time they were floated in a 37 °C water bath for 90 min. After incubation, plates were tilted at a 45° angle to their long axis for 20 min at room temperature, and then scanned to record the reaction of hemagglutination by natural antibodies. Plates were then kept at room temperature for an additional 70 min, and scanned for a second time to record complement-mediated maximum hemolysis. Quantification of hemagglutination and hemolysis was done by assessing the dilution stage (on a scale from 1 to 12) at which these two reactions stopped. It was not always possible to collect a blood sample from all captured individuals, therefore this analysis was conducted for samples from 59 individuals (27 males and 32 females).

Data analyses

Hemolyisis, hemagglutination and CORT were not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test; W < 0.63, p < 0.05). Although the hemolysis scores ranged from 0 to 4, this reaction was absent in 42 % of the individuals. Therefore, hemolysis scores were treated as a binary variable, i.e., ‘0’ (score 0; no hemolysis) or ‘1’ (score >0; lysis). Hemolysis and hemagglutination were not correlated (Spearman r = 0.182, p = 0.14, n = 66). Hemolysis and CORT were also not correlated (Spearman r = −0.084, p = 0.52, n = 60), nor was hemagglutination and CORT (Spearman r = −0.077, p = 0.56, n = 60). Therefore, these three variables were considered to be dependent variables in three independent models. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on the 5 pollutants (PM10, O3, SO2, CO, and NOx) for each one of our study sites. PCA is an analytic method that has been successfully used to determine Air Quality in recent decades (Smeyers-Verbeke et al., 1984; Chavent et al., 2008). PCA can identify relationships between the studied pollutants, and uncover patterns of air pollution (Voukantsis et al., 2011). The PC1 accounted for 83% of the total variance. PC1 was strongly positively related to 03 concentration and strongly negatively related to the other four pollutants (Table 1). We used the values of the PC1 as an “ozone gradient” for our analyses. We performed another PCA with the six anthropogenic variables: Human population density, housing density, industry density, and land-use. The PC1 obtained in this analysis accounted for 54% of the total variance. PC1 scores were strongly positively related to human population, housing densities, and urban land. The scores close to zero were related to the density of industrial complexes. Lower scores in the PC1 were associated with a higher percentage of both agricultural and forest land (Table 1). As a result, we used the values of this PC1 as an “urban gradient”. We applied three generalized linear models (GzLM) with hemolysis (using a Binomial distribution and the complementary logit- link function), hemagglutination (using a Multinomial distribution and the complementary log- link function), and CORT (using a Normal distribution and the log link function) as dependent variables. Residuals were normally distributed after CORT was log-transformed (Shapiro-Wilk test; W = 0,98, p = 0.50). The three models included sex as a fixed factor and ozone gradient and urban gradient as covariates. We also included in each model the scaled mass index as a covariate to control for the potential effect of the body condition on the physiology, as well as all possible interactions between variables. The model selection was conducted by analyzing the distribution of our data and selecting for the models with the lowest AICc values (Akaike, 1974). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 23, IBM Inc., NY, USA).

Results

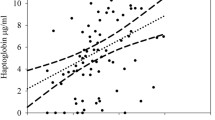

Each study area was characterized by means of the two PCAs into both an ozone and an urban gradient. Tlahuac was the most ozone-contaminated but least urbanized study site. Tlaneplanta was the least ozone-contaminated area and Iztapalapa-UAM the most urbanized (Table 2). The Binomial Model showed that hemolysis did not relate to any of variables (Table 3; Fig. 2a.). GzLMs showed that hemagglutination was negatively related to the ozone gradient (Table 3; Fig. 2b.). However, the urban gradient, the scaled mass index, and sex were not related to this immune response. Finally, only sex was marginally related to the CORT concentration in feather; females had higher CORT in their feathers than males, although this difference was not significant (Table 3). The ozone gradient, the urban gradient, and the scaled mass index were also not related to the stress response (Table 3; Fig. 2c.). No interactions between variables were included in the three models with the lowest AICs (p > 0.05). Full models have been added as supplements (Supplements 1, 2, and 3), as well as a supplementary table (Supplement 4) with raw data and information on each house sparrow sampled.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the influence of air pollution on the physiological stress (measured as CORT levels in feathers) and immune response (natural antibodies and complement system activity) of house sparrows living in MCMA. We did not find a significant influence of air pollution on the CORT concentrations or on the complement system activity of house sparrows. However, individuals captured at sites with a high concentration of ozone showed a reduction in natural antibody activity compared to those captured at sites with lower ozone concentrations. These results suggest that ozone concentrations in air pollution within MCMA may constrain the natural antibody response in the immune system of house sparrows.

As predicted, we found a negative relationship between air pollution and immune response in house sparrows. Exposure to ozone has been linked to adverse health effects in humans, including increased rates of visits to the hospital, exacerbation of chronic respiratory conditions (eg, asthma), decreased lung function, and increased mortality counts (Bell et al., 2004; Bell et al., 2007; Fann et al., 2015). Ozone increases the production of free radicals, which promotes a state of oxidative stress in eukaryotic aerobic organisms that is implicated in a wide variety of degenerative diseases (Kampa and Castanas, 2008). Several studies on mammals have shown functional, structural, and biochemical alterations caused by acute and/or chronic exposures to ozone concentrations (Dorado-Martínez et al., 2001; Valacchi et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2006; Ramot et al., 2015).

A recent study has shown large-scale evidence that air pollution, specifically ozone, is associated with declines in bird abundance in the United States (Liang et al., 2020). However, the effects of ozone on the physiology of birds is still poorly known. In general, ozone, as well other factors (e.g., temperature, ultraviolet light, mycotoxins, ammonia), is considered a potential avian stressor (Davison et al., 2008). However, few avian studies corroborate this hypothesis. An experimental study (Rombout et al., 1991) conducted on Japanese quails (Coturnix japonica) showed harmful effects of ozone on their lungs. Individuals continuously exposed to different ozone concentrations for 7 days showed a loss of cilia in the trachea and bronchi, an inflammatory response, necrosis of air capillary epithelial cells, and extensive hemorrhages, among other adverse effects. Since no signs of repair in the air capillary epithelium occurred after 7 days of continuous exposure, the authors concluded that quail seems to lack the morphological and biochemical ability to repair this tissue that has been observed in mammals (van Bree et al., 2001, but see: Gorriz et al., 1994). If this lack of repair capacity is found in more species, birds could be a group especially vulnerable to ozone. There is evidence that high concentrations of ozone have a negative effect on both adaptive and innate immune responses in mammals (reviewed in Jakab et al., 1995). In the case of the innate immune system, most of the studies assessing the effect of ozone are focused on macrophages and neutrophils, which are involved in phagocytosis of pathogens and inflammatory responses. These studies have shown that ozone reduces phagocytosis activity (Becker et al., 1991; Hollingsworth et al., 2007; Valentine, 1985) and impairs clearance in several species (Gilmour et al., 1993; Miller and Ehrlich, 1958). However, it should be noted that the pollutant concentrations to which the animals were subjected in these studies exceeded the concentrations the sparrows in our study were exposed to. Therefore, experimental studies at pollutant concentrations closer to natural conditions are needed to understand the true health risk faced by animals in the field.

The likelihood of humoral immunity perturbation by ozone is not known, especially with regard to naturally occurring antibodies (Nabs) and the complement system, which are components of the humoral innate immune response. Our study shows that individuals captured at sites with high levels of ozone had a diminished hemagglutination response. The hemagglutination response is measured to estimate the levels of circulating natural antibodies. A high hemagglutination response is related to high Nabs levels (Matson et al., 2005). Nabs are antibodies produced by B lymphocytes, essentially of the immunoglobulin M (IgM) isotype, although both immunoglobulins G (IgG) and A (IgA) isotypes have also been reported as Nabs (Panda and Ding, 2015). The production of IgGs and IgAs decreases in the presence of ozone, which has been shown in human B lymphocytes in vitro (Becker et al. 1991) and in mice (Gil-mour and Jakab, 1991). These results suggests that Nabs production could be limited by ozone exposure. However, experimental studies are necessary to corroborate our findings.

Natural antibodies activate the classical complement pathway leading to lysis, which reflects the interaction of complement and Nabs (Matson et al. 2005), if high ozone concentration decreases circulating Nabs levels, a decrease in the hemolysis response may also be expected. However, we did not find a relationship between ozone contamination and hemolysis. This result may reflect different fitness costs of maintaining Nabs and the complement system. Substantial nutritional and energetic costs are associated with maintenance of a normal immune system (Lochmiller and Deerenberg 2000). The development and maintenance of natural antibodies in birds is not entirely understood, but it is thought to require stimulation of an acquired immune system via B-1 cells by auto-antigens (Parmentier et al., 2004; Haghighi et al., 2006). This may be more costly than the development of defenses that depend on the innate immune system (i.e: complement system), a process that has been characterized as inexpensive (Lee 2006; Lee et al. 2008). Therefore, in adverse conditions, where the individual must face strong physiological trade-offs, it could be expected that the most costly response (i.e: Nabs response) is the most compromised.

Natural antibodies establish the first line of defense against invading pathogens, therefore an inefficient response of these components may be detrimental to the organisms (Matson et al., 2005). Lee and Klasing (2004) predicted that house sparrows (considered an invasive species and a good invader of new sites; Lee 2002) may have a weak systemic inflammatory response, but a stronger humoral response compared to a poor invader. This is because systemic inflammation is costly both metabolically and behaviorally, and a good invader requires high energy for growth and reproduction; adaptations which favor the capacity to invade (Klasing and Korver, 1997; Bonneaud et al., 2003). In addition to their in the defense against invading pathogens, Nabs also have a regulatory role in anti-inflammatory reactions, essential to avoid systemic diseases (Schwartz-Albiez et al., 2009). Therefore, by living in high ozone concentration areas where the Nabs response is limited, the ability for house sparrows to expand their population could be restricted. Ozone is unlikely to be the only cause of the diminished immune response in house sparrows, but it may contribute through indirect effects. Future studies evaluating the effects of ozone on humoral innate immunity are necessary to know the global effect of the pollutant on the immune system of this organism and other bird species. It is important to point out that the relationship between Nabs activity and ozone gradient found here cannot explain all of the variability observed in the hemagglutination response. Other factors which may also impact this response, but not considered in this study, include parasitic load, reproductive status, and/or age. These factors cause such high immune variability (e.g Christe et al., 2000; de Lope et al., 1998; Morales et al., 2004 for parasitic load; Nordling et al., 1998, Hanssen et al., 2005 for status reproductive; De Coster et al., 2010, Stambaugh et al., 2011 for age). Further experimental studies are necessary to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving variability in the innate response. Additionally, although ozone does effect the house sparrow immune system, the mechanism for how this occurs is not obvious. Perhaps, it may be related to an acclimation process. Acclimation is a phenotypic response to an environmental challenge that may improve an organism’s ability to survive under severe environmental conditions (Hoffmann, 1995). Such responses occur in many organisms faced with different anthropogenic challenges (Yauk et al., 2001). As we have said above, the house sparrow is an invasive species and one of the reasons for its widespread success may be due precisely to its ability to acclimatize to anthropogenic environments, and it is very likely that the effect of the ozone on other species that are not so ubiquitous would be more dramatic.

Contrary to our expectations, we did not find that air pollution or the urban gradient had a significant influence on CORT concentrations in the house sparrow. This finding is supported by other studies on endocrine ecology in this species (Eeva et al., 2005; Fokidis et al., 2009; Bókony et al., 2012; Meillère et al., 2015), but not by work carried out in other avian species (e.g., see Fokidis et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011; Meillère et al., 2016;). The range of values recorded in this study for CORT feather concentration (∼3–39 pg CORT/mm feather), with the lowest values being thirteen times lower than the highest ones, is even higher than the range of values recorded by other studies that have reported avian stress using feather samples (Lattin et al., 2011; Legagneux et al., 2013; Will et al., 2014). Therefore, it seems that house sparrows included in our study may be stressed, however, this response is independent of both air pollution and urbanization gradients.

Several authors have concluded that the relationship between urbanization and CORT levels is inconsistent and species dependent, and impacted by life-history stage, age, sex, and the specific constraints of a given urban habitat (reviewed in Bonier, 2012). Sex, reproductive status, and food availability, could all have masked the effects of urbanization or air pollution on stress physiology (Dantzer et al., 2014). In fact, our results show marginally significant sexual differences in CORT, where females had higher CORT concentrations than males. Such difference could be caused by sex-specific costs of reproduction in house sparrows. In this species, females have an extra cost during reproduction, which could increase their CORT levels above those present in males. This hypothesis is supported by the findings of Bortolotti and colleagues (2008), who reported a positive relationship between CORT in feathers in the summer and fall, and a reproductive investment in eggs in the spring and summer for females of house sparrows this species. These authors suggest that elevated HPA activity during egg laying in female birds is costly, thus CORT levels found here could indicate that egg production is stressful, or that the current reproductive investment reduces the subsequent resistance to stress. It is noteworthy, that the exact period of molt is unknown for each individual in our study. We had to make certain assumptions about the timing of molts, though feathers grow at the same time when conditions are equivalent for individuals in the same place, for example in terms of food availability (Romero and Fairhurst, 2016). This together with sex distribution is not strictly homogeneus along our study area, and thus could be masking the effect of ozone pollution on stress level of house sparrows.

Conclusion

Ozone is considered one of the most harmful constituents of the lower atmosphere because it acts as a major oxidizing agent (Alloway and Ayres, 1997). It is a green-house gas that affects the growth of plants (Krupa et al., 2001), causes adverse effects on human health (Kampa and Castanas 2008), and is related to the decline of bird populations (Liang et al., 2020). Despite numerous governmental campaigns focused on improving the air quality in the MCMA, ozone concentrations remain high and is the air pollutant that exceeds the environmental standards more days per year (more than 100 days/year; Benitez-Garcia et al., 2015; Jaimes-Palomera et al., 2016). The present study shows the potential impact of ozone pollution on a wild species in the MCMA for the first time, using Nabs activity as an indicator to assess the effect of air contamination on wildlife. This effect could be expected in more species. House sparrow populations are on the decline globally, and many causes have been suggested to explain this decline, including agricultural management (Wretenberg et al. 2006), habitat loss, and human influence (Hole et al., 2002, Shaw et al., 2008). Our results suggest that ozone may be a factor limiting the expansion of this species and may be playing a role in the observed population declines at large urban sites (Summers-Smith, 2003). Future studies in house sparrows and native species of Mexico should be performed to understand the noxious effects of ozone on the avian community. The results of such studies could be useful for managing bird populations inside polluted cities.

References

Akaike H (1974) A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Control 19:716–723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

Alexis NE, Lay JC, Hazucha M, Harris B, Hernandez ML, Bromberg PA, Kehrl H, Diaz-Sanchez D, Kim C, Devlin RB, Peden DB (2010) Low-level ozone exposure induces airways inflammation and modifies cell surface phenotypes in healthy humans. Inhal Toxicol 22:593–600. https://doi.org/10.3109/08958371003596587

Alloway JB, Ayres DC (1997) Chemical principles of environmental pollution. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Becker S, Quay J, Koren HS (1991) Effect of ozone on immunoglobulin production by human B cells in vitro. J Toxicol Environ Health Sci 34:353–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287399109531573

Bell M, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM, Dominici F (2004) Ozone and short-term mortality in 95 US Urban Communities, 1987–2000. JAMA 292:2372–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.19.2372

Bell ML, Goldberg R, Hogrefe C, Kinney PL, Knowlton K, Lynn B, Rosenthal J, Rosenzweig C, Patz JA (2007) Climate change, ambient ozone, and health in 50 US cities. Clim Chang 82:61–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9166-7

Benítez-García SE, Kanda I, Wakamatsu S, Okazaki Y, Kawano M (2015) Investigation of vertical profiles of meteorological parameters and ozone concentration in the Mexico City metropolitan area. Asian J Atmos Environ 9:114–127. https://doi.org/10.5572/ajae.2015.9.2.114

Blas J, Baos R, Bortolotti GR, Marchant T, Hiraldo F (2005) A multi‐tier approach to identifying environmental stress in altricial nestling birds. Funct Ecol 19:315–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.00976.x

Bókony V, Kulcsár A, Liker A (2010) Does urbanization select for weak competitors in house sparrows? Oikos 119:437–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17848.x

Bókony V, Seress G, Nagy S, Lendvai ÁZ, Liker A (2012) Multiple indices of body condition reveal no negative effect of urbanization in adult house sparrows. Landsc Urban Plan 104:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.10.006

Bonier F (2012) Hormones in the city: endocrine ecology of urban birds. Horm Behav 61:763–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.03.016

Bonneaud C, Mazuc J, Gonzalez G, Haussy C, Chastel O, Faivre B, Sorci G (2003) Assessing the cost of mounting an immune response. Am Nat 161:367–379. https://doi.org/10.1086/346134

Bortolotti GR, Marchant TA, Blas J, German T (2008) Corticosterone in feathers is a long‐term, integrated measure of avian stress physiology. Funct Ecol 22:494–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01387.x

van Bree L, Dormans JAMA, Boere AJF, Rombout PJA (2001) Time study on development and repair of lung injury following ozone exposure in rats. Inhal Toxicol 13:703–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/08958370126868

Brown RE, Brain JD, Wang N (1997) The avian respiratory system: a unique model for studies of respiratory toxicosis and for monitoring air quality. Environ Health Perspect 105:188–200. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.97105188

Calderón-Garcidueñas L, Torres-Jardón R, Kulesza RJ, Park SB, D’Angiulli A (2012) Air pollution and detrimental effects on children’s brain. The need for a multidisciplinary approach to the issue complexity and challenges. Fron Hum Neurosci 8:613. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00613

Calderón-Garcidueñas L, Kulesza RJ, Doty RL, D’angiulli A, Torres-Jardón R (2015) Megacities air pollution problems: Mexico City Metropolitan Area critical issues on the central nervous system pediatric impact. Environ Res 137:157–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.12.012

Carbajal-Arroyo L, Miranda-Soberanis V, Medina-Ramón M, Rojas-Bracho L, Tzintzun G, Solís-Gutiérrez P, Romieu I (2010) Effect of PM10 and O3 on infant mortality among residents in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area: a case-crossover analysis, 1997–2005. J Epidemiol Community Health 65:715–721. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.101212

Chatelain M, Gasparini J, Jacquin L, Frantz A (2014) The adaptive function of melanin-based plumage coloration to trace metals. Biol Lett 10:20140164. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2014.0164

Chavent M, Guιgan H, Kuentz V, Patouille B, Saracco J (2008) PCA- and PMF-based methodology for air pollution sources identification and apportionment. Environmetrics 20:928–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/env.963

Christe P, Møller AP, Saino N, Lope F (2000) Genetic and environmental components of phenotypic variation in immune response and body size of a colonial bird, Delichon urbica (the house martin). Heredity 85:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00732.x

CONAPO (2012) Consejo Nacional de Población, Delimitación de las zonas metropolitanas de México 2010. Secretaría de Desarrollo Social, Consejo Nacional de Población, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, Mexico

Cruz-Martinez L, Fernie KJ, Soos C, Harner T, Getachew F, Smits JE (2015) Detoxification, endocrine, and immune responses of tree swallow nestlings naturally exposed to air contaminants from the Alberta oil sands. Sci Tot Environ 502:8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.09.008

De Coster G, De Neve L, Martín-Gálvez D, Therry L, Lens L (2010) Variation in innate immunity in relation to ectoparasite load, age and season: a field experiment in great tits (Parus major). J Exp Biol 213:3012–3018. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.042721

Dantzer B, Fletcher QE, Boonstra R, Sheriff MJ (2014) Measures of physiological stress: a transparent or opaque window into the status, management and conservation of species? Conserv Physiol 2:cou023. https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/cou023

Davison F, Schat K, Kaspers B, Kaiser P (2008) Avian Immunology. Academic Press, London

Deem SL, Parker PG, Cruz MB, Merkel J, Hoeck PEA (2011) Comparison of blood values and health status of floreana mockingbirds (Mimus Trifasciatus) on the islands of champion and gardner-by-floreana Galápagos islands. J. Wildlife Dis. 47:94–106. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-47.1.94

Dorado-Martínez C, Paredes-Carbajal C, Mascher D, Borgonio-Pérez G, Rivas-Arancibia S (2001) Effects of different ozone doses on memory, motor activity and lipid peroxidation levels, in rats. Int J Neurosci 108:149–161. https://doi.org/10.3109/00207450108986511

Eeva T, Lehikoinen E, Nikinmaa M (2005) Pollution-related effects on immune function and stress in a free-living population of pied flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca. J Avian Biol 36:405–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0908-8857.2005.03449.x

Fann N, Nolte CG, Dolwick P, Spero TL, Brown AC, Phillips S, Anenberg S (2015) The geographic distribution and economic value of climate change-related ozone health impacts in the United States in 2030. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 65:570–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2014.996270

Fokidis HB, Orchinik M, Deviche P (2009) Corticosterone and corticosteroid binding globulin in birds: relation to urbanization in a desert city. Gen Comp Endocrinol 160:259–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.12.005

Furness RW (1993) Birds as monitors of pollutants. In: Furness RW, Greenwood JJD (eds) Birds as monitors of environmental change. Chapman and Hall, London, p 86–143. 10.1007/978-94-015-1322-7_3

Gilmour M, Park P, Doerfler D, Selgrade M (1993) Factors that influence the suppression of pulmonary antibacterial defenses in mice exposed to ozone. Exp Lung Res 19:299–314. https://doi.org/10.3109/01902149309064348

Gilmour MI, Jakab GJ (1991) Modulation of immune function in mice exposed to 0.8 ppm ozone. Inhalation Toxicol 3:293–308. https://doi.org/10.3109/08958379109145290

Gorriz A, Llacuna S, Durfort M, Nadal J (1994) A study of the ciliar tracheal epithelium on passerine birds and small mammals subjected to air pollution: ultrastructural study. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 27:137–42

Grinnell J (1919) The English sparrow has arrived in death valley: an experiment in nature. Amer Naturalist 53:468–472

Haghighi HR, Gong J, Gyles CL, Hayes MA, Zhou H, Sanei B, Chambers JR, Sharif S (2006) Probiotics stimulate production of natural antibodies in chickens. Clin Vaccine Immunol 13:975–980. https://doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00161-06

Hanssen SA, Hasselquist D, Folstad I, Erikstad KE (2005) Cost of reproduction in a long-lived bird: incubation effort reduces immune function and future reproduction. Proc R Soc B 272:1039–1046. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3057

Héroux ME, Anderson HR, Atkinson R, Brunekreef B, Cohen A, Forastiere F, Hurley F, Katsouyanni K, Krewski D, Krzyzanowski M, Künzli N, Mills I, Querol X, Ostro B, Walton H (2015) Quantifying the health impacts of ambient air pollutants: recommendations of a WHO/Europe project. Int J Public Health 60:619–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-015-0690-y

Herrera-Dueñas PJ, Antonio MT, Aguirre JI (2014) Oxidative stress of House Sparrow as bioindicator of urban pollution. Ecol Indic 42:6–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.08.014

Hiltermann TJ, Peters EA, Alberts B, Kwikkers K, Borggreven PA, Hiemstra PS, Dijkman JH, van Bree LA, Stolk J (1998) Ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with asthma: role of neutrophil-derived serine proteinases. Free Radic Biol Med 24:952–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00381-X

Hoffmann AA (1995) Acclimation: increasing survival at a cost. Trends Ecol. Evol 10:1–2

Hole DG, Whittingham MJ, Bradbury RB, Anderson GQ, Lee PL, Wilson JD, Krebs JR (2002) Widespread local house-sparrow extinctions. Nature 418:931–932. https://doi.org/10.1038/418931a

Hollingsworth JW, Kleeberger SR, Foster WM (2007) Ozone and pulmonary innate immunity. Proc Am Thorac Soc 4:240–246. https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.200701-023aw

Holmes WN, Phillips JG (1976) The adrenal cortex in birds. In: Chester-Jones I, Henderson I (eds) General and comparative endocrinology of the adrenal cortex. Academic Press, New York, p 293–420

Isaksson C, Andersson MN, Nord A, von Post M, Wang Hong-Lei (2017) Species-dependent effects of the urban environment on fatty acid composition and oxidative stress in birds. Front Ecol Evol 5:44. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2017.00044

Jaimes-Palomera M, Retama A, Elias-Castro G, Neria-Hernández A, Rivera-Hernández O, Velasco E (2016) Non-methane hydrocarbons in the atmosphere of Mexico City: Results of the 2012 ozone-season campaign. Atmos Environ 132:258–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.02.047

Jakab GJ, Spannhake EW, Canning BJ, Kleeberger SR, Gilmour MI (1995) The effects of ozone on immune function. Environ Health Perspect 103:77. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.95103s277

Kampa M, Castanas E (2008) Human health effects of air pollution. Environ Pollut 151:362–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.012

Kekkonen J, Hanski IK, Väisänen RA, Brommer JE (2012) Levels of heavy metals in House Sparrows (Passer domesticus) from urban and rural habitats of southern Finland. Ornis Fenn 89:91–98

Klasing KC, Korver DR (1997) Leukocytic cytokines regulate growth rate and composition following activation of the immune system. J Anim Sci 75:58–67

Krupa SV, McGrath MT, Andersen CP, Booker FL, Burkey KO, Chappelka AH, Chevone BI, Pell EJ, Zilinskas BA (2001) Ambient ozone and plant health. Plant Dis 85:4–12. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS.2001.85.1.4

Lattin CR, Reed JM, DesRochers DW, Romero LM (2011) Elevated corticosterone in feathers correlates with corticosterone-induced decreased feather quality: a validation study. J Avian Biol 42:247–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-048X.2010.05310.x

Lee CE (2002) Evolutionary genetics of invasive species. Trends Ecol Evol 17:386–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02554-5

Lee KA (2006) Linking immune defenses and life history at the levels of the individual and the species. Integr Comp Biol 46:1000–1015. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icl049

Lee KA, Klasing KC (2004) A role for immunology in invasion biology. Trends Ecol Evol 19:523–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.012

Lee KA, Wikelski M, Robinson WD, Robinson TR, Klasing KC (2008) Constitutive immune defences correlate with life‐history variables in tropical birds. J Anim Ecol 77:356–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01347.x

Legagneux P, Harms NJ, Gauthier G, Chastel O, Gilchrist HG, Bortolotti G, Bêty J, Soos C (2013) Does feather corticosterone reflect individual quality. PLoS One 8:e82644. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082644

Liang Y, Rudik I, Zou EY, Johnston A, Rodewald AD, Kling CL (2020) Conservation cobenefits from air pollution regulation: Evidence from birds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:30900–30906. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2013568117

Liker A, Papp Z, Bókony V, Lendvai ÁZ (2008) Lean birds in the city: body size and condition of house sparrows along the urbanization gradient. J Anim Ecol 77:789–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01402.x

Lochmiller RL, Deerenberg C (2000) Trade‐offs in evolutionary immunology: just what is the cost of immunity? Oikos 88:87–98. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880110.x

de Lope F, Møller AP, de la Cruz C (1998) Parasitism, immune response and reproductive success in the house martin Delichon urbica. Oecologia 114:188–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050435

Lorz C, Lopez J (1997) Incidence of air pollution in the pulmonary surfactant system of the pigeon (Columba livia). Anat Rec 249:206–212. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199710)249:2<206::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-V

Manisalidis I, Stavropoulou E, Stavropoulos A, Bezirtzoglou E (2020). Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: a review. Frontiers in public health 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00014

Mannucc PM, Harari S, Martinelli I, Franchini M (2015) Effects on health of air pollution: a narrative review. Intern Emerg Med 10:657–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-015-1276-7

Matson KD, Ricklefs RE, Klasing KC (2005) A hemolysis–hem hemagglutination assay for characterizing constitutive innate humoral immunity in wild and domestic birds. Dev Comp Immunol 29:275–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2004.07.006

Meillère A, Brischoux F, Parenteau C, Angelier F (2015) Influence of urbanization on body size, condition, and physiology in an urban exploiter: a multi-component approach. PLoS One 10:e0135685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.12.014

Meillère A, Brischoux F, Henry PY, Michaud B, Garcin R, Angelier F (2017) Growing in a city: Consequences on body size and plumage quality in an urban dweller, the house sparrow (Passer domesticus). Landsc Urban Plan 160:127–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.12.014

Meillère A, Brischoux F, Bustamante P, Michaud B, Parenteau C, Marciau C, Angelier F (2016) Corticosterone levels in relation to trace element contamination along an urbanization gradient in the common blackbird (Turdus merula). Sci Total Environ 566:93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.014

Millaku L, Resmije I, Artan T (2014) House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) as bioindicator of heavy metals pollution. Eur J Exp Bio 4:77–80

Miller DB, Ghio AJ, Karoly ED, Bell LN, Snow SJ, Madden MC, Soukup J, Cascio WE, Gilmour MI, Kodavanti UP (2016) Ozone exposure increases circulating stress hormones and lipid me-tabolites in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193:1382–1391

Miller S, Ehrlich R (1958) Susceptibility to respiratory infections of animals exposed to Ozone: I. Susceptibility to” Klebsiella Pneumoniae”. J Infect Dis 103:145–149

Molina MJ, Molina LT (2004) Megacities and atmospheric pollution. Air Waste Manag Assoc 54:644–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/10473289.2004.10470936

Møller AP, Haussy C (2007) Fitness consequences of variation in natural antibodies and complement in the barn swallow Hirundo rustica. Funct Ecol 21:363–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01215.x

Morales J, Moreno J, Merino S, Tomas G, Martinez J, Garamszegi LZ (2004) Associations between immune parameters, parasitism, and stress in breeding piedflycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca) females. Can J Zool 82:1484–1492. https://doi.org/10.1139/z04-132

Nebel S, Bauchinger U, Buehler DM, Langlois LA, Boyles M, Gerson AR, Guglielmo CG (2012) Constitutive immune function in European starlings, Sturnus vulgaris, is decreased immediately after an endurance flight in a wind tunnel. J Exp Biol 215:272–278. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.057885

Nordling D, Andersson M, Zohari S, Gustafsson L (1998) Reproductive effort reduces specific immune response and parasite resistance. – Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265:1291–1298

North MA, Kinniburgh DW, Smits JEG (2017) European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) as sentinels of urban air pollution: A comprehensive approach from non-invasive to post mortem investigation. Environ Sci Technol 51:8746–8756. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b01861

Nossen I, Ciesielski TM, Dimmen MV, Jensen H, Ringsby TH, Polder A, Rønning B, Jenssen BM, Styrishave B (2016) Steroids in house sparrows (Passer domesticus): effects of POPs and male quality signalling. Sci Total Environ 547:295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.113

Oakes JL, O’Connor BP, Warg LA, Burton R, Hock A, Loader J, Laflamme D, Jing J, Hui L, Schwartz DA, Yang IV (2013) Ozone enhances pulmonary innate immune response to a TLR2 agonist. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 48:27–34. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2012-0187OC

Palacios MG, Cunnick JE, Winkler DW, Vleck CM (2012) Interrelations among immune defense indexes reflect major components of the immune system in a free-living vertebrate. Physiol Biochem Zool 85:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1086/663311

Panda S, Ding J (2015) Natural antibodies bridge innate and adaptive immunity. J. Immunol 194:13–20. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1400844

Parejo D, Silva N (2009) Immunity and fitness in a wild population of Eurasian kestrels Falco tinnunculus. Naturwissenschaften 96:1193–1202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-009-0584-z

Parmentier HK, Lammers A, Hoekman JJ, Reilingh GDV, Zaanen IT, Savelkoul HF (2004) Different levels of natural antibodies in chickens divergently selected for specific antibody responses. Dev Comp Immunol 28:39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-305X(03)00087-9

Peig J, Green AJ (2010) The paradigm of body condition: A critical reappraisal of current methods based on mass and length. Funct Ecol 24:1323–1332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01751.x

Pigeon G, Belisle M, Garant D, Cohen AA, Pelletier F (2013) Ecological immunology in a fluctuating environment: an integrative analysis of tree swallow nestling immune defense. Ecol Evol 3:1091–1103. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.504

Pinowski J, Barkowska M, Kruszewicz AH, Kruszewicz AG (1994) The causes of the mortality of eggs and nestlings of Passer spp. J Biosci 19:441–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02703180

Rajagopalan S, Brook RD (2016) Ozone-induced metabolic effects in humans: ieiunium, conviviorum, aut timor? (fasting, feasting, or fear?). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193:1327–1329. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201601-0142ED.

Ramot Y, Kodavanti UP, Kissling GE, Ledbetter AD, Nyska A (2015) Clinical and pathological manifestations of cardiovascular disease in rat models: the influence of acute ozone exposure. Inhal Toxicol 27:26–38. https://doi.org/10.3109/08958378.2014.954168

Riojas-Rodriguez H, Alamo-Hernandez U, Texcalac-Sangrador JL, Romiu I (2014) Health impact assessment of decreases in PM10 and ozone concentrations in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. A basis for a new air quality management program. Salud Pública Mexico 6:579e591

Rombout PJA, Dormans JAMA, Van Bree L, Marra M (1991) Structural and biochemical effects in lungs of Japanese quail following a 1-week exposure to ozone. Environ Res 54:39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-9351(05)80193-8

Romero LM (2004) Physiological stress in ecology: lessons from biomedical research. Trends Ecol Evol 19:249–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.008

Romero LM, Fairhurst DG (2016) Measuring corticosterone in feathers: strengths, limitations, and suggestions for the future. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A 202:112–122

Romieu I, Gouveia N, Cifuentes LA, de Leon AP, Junger W, Vera J, Carbajal-Arroyo L (2012) Multicity study of air pollution and mortality in Latin America (the ESCALA study). Research report (Health Effects Institute) 171:5–86

Salmón P, Nilsson J, Nord A, Bensch S, Isaksson C (2016) Urban environment shortens telomere length in nestling great tits, Parus major. Biol Lett 12:20160155. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0155

Salmón P, Stroh E, Herrera-Dueñas A, von Post M, Isaksson C (2018) Oxidative stress in birds along a NOx and urbanisation gradient: an interspecific approach. Sci Total Environ 622–623:635–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.354

Sanderfoot OV, Holloway T (2017) Air pollution impacts on avian species via inhalationexposure and associated outcomes. Environ Res Lett 12:083002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa805

Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU (2000) How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev 21:55–89. https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389

Schilderman PAEL, Hoogewerff JA, Van Schooten FJ, Maas LM, Moonen EJC, Van Os BJH, Van Wijnen JH, Kleinjans JCS (1997) Possible relevance of pigeons as an indicator species for monitoring air pollution. Environ Health Perspect 105:322–330. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.97105322

Schwartz-Albiez R, Monteiro RC, Rodriguez M, Binder CJ, Shoenfeld Y (2009) Natural antibodies, intravenous immunoglobulin and their role in autoimmunity, cancer and inflammation. J Clin Exp Immunol 158:43–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04026.x

Schwela D (2000) Air pollution and health in urban areas. Rev Environ Health 15:13–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/REVEH.2000.15.1-2.13

Secretaria del Medio Ambiente de la Ciudad de México SEDEMA (2016) Informe Anual de la Calidad del aire en la Ciudad de México

Shaw LM, Chamberlain D, Evans M (2008) The House Sparrow Passer domesticus in urban areas: reviewing a possible link between post-decline distribution and human socioeconomic status. J Ornithol 149:293–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-008-0285-y

Smeyers-Verbeke J, Den Hartog JC, Dehker WH, Coomans D, Buydens L, Massart DL (1984) The use of principal components analysis for the investigation of an organic air pollutants data set. Atmos Environ 18:2471–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(84)90017-9

Stambaugh T, Houdek BJ, Lombardo MP, Thorpe PA, Hahn DC (2011) Innate immune response development in nestling tree swallows. Wilson J Ornithol 123:779–787. https://doi.org/10.1676/10-197.1

Summers-Smith JD (2003) The decline of the House Sparrow: a review. Br Birds 96:439–446

Swaileh KM, Sansur R (2006) Monitoring urban heavy metal pollution using the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus). J Environ Monit 8:209–213. https://doi.org/10.1039/B510635D

Valacchi G, Van der Vliet A, Schock BC, Okamoto T, Obermuller-Jevic U, Cross CE, Packer L (2002) Ozone exposure activates oxidative stress responses in murine skin. Toxicology 179:163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00240-8

Valentine R (1985) An in vitro system for exposure of lung cells to gases: effects of ozone on rat macrophages. J Toxicol Environ Health 16:115–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287398509530723

Vermeulen A, Muller W, Matson KD, Tieleman BI, Bervoets L, Eens M (2015) Sources of variation in innate immunity in great tit nestlings living along a metal pollution gradient: an individual-based approach. Sci Total Environ 508:297–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.11.095

Voukantsis D, Karatzas K, Kukkonen J, Räsänen T, Karppinen A, Kolehmainen M (2011) Intercomparison of air quality data using principal component analysis, and forecasting of PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations using artificial neural networks, in Thessaloniki and Helsinki. Sci Total Environ 409:1266–1276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.12.039

Wang C, Lin J, Niu Y, Wang W, Wen J, Lv L, Liu C, Du X, Zhang Q, Chen B, Cai J, Zhao Z, Liang D, Sji J, Chen H, Chen R, Kan H (2022) Impact of ozone exposure on heart rate variability and stress hormones: a randomized-crossover study. J Hazard Mater 421:126750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126750

Wang J, Wang S, Manzer R, McConville G, Mason RJ (2006) Ozone induces oxidative stress in rat alveolar type II and type I-like cells. Free Radi Biol Med 40:1914–1928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.017

WHO (1997) WHO Guidelines for Air Quality. December. WHO Information Fact Sheet no. 187

Will A, Suzuki Y, Elliot KH, Hatch SA, Watanuki Y, Kitaysky AS (2014) Feather corticosterone reveals developmental stress in seabirds. J Exp Biol 217:2371–2376. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.098533

Wingfield JC, Ramenofsky M (1999) Hormones and the behavioral ecology of stress. In: Baum PHM (ed) Stress physiology in animals. Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield, p 1–51

Wingfield JC, Romero LM (2001) Adrenocortical responses to stress and their modulation in free-living vertebrates. In: McEwens BS (ed) Handbook of physiology. Section 7: The endocrine system. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 211–236

Wingfield JC, Sapolsky RM (2003) Reproduction and resistance to stress: When and how (Review). J Neuroendocrinol 15:711–724

Wretenberg J, Lindström Å, Svensson S, Thierfelder T, Pärt T (2006) Population trends of farmland birds in Sweden and England: similar trends but different patterns of agricultural intensification. J Appl Ecol 43:1110–1120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01216.x

Xia Y, Niu Y, Cai J, Liu C, Meng X, Chen R, Kan H (2022) Personal ozone exposure and stress hormones in the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal and sympathetic-adrenal-medullary axes. Environ. Int. 159:107050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.107050

Yauk CL, Smits JE, Quinn JS, Bishop CA (2001) Pulmonary histopathology in ring-billed gulls (Larus delawarensis) from colonies near steel mills and in rural areas. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 66:563–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001280045

Zhang S, Lei F, Liu S, Li D, Chen C, Wang P (2011) Variation in baseline corticosterone levels of tree Sparrow (Passer montanus) populations along an urban gradient in Beijing, China. J. Ornithol 152:801–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0663-8

Acknowledgements

We thank Secretaría de Medio Ambiente de la Ciudad de México, which provided us with air pollution data. Armando Retama and Miguel Sánchez played a crucial role in this project by providing logistic support. Ricardo Valdez helped us with some laboratory assays. Danielle Lee Burnett revised the English.

Author contributions

CS and JES conceived of the idea. Field work was carried out by CS. Lab work was done by CS, CACZ, ILR, MCR. CS wrote the manuscript. All authors revised and edited the MS. JES and ILR provided funding.

Funding

Research funding was granted to JES by PAPIIT-UNAM (project no. IN212216). This work is part of a postdoctoral research project of C.S in the DGAPA-UNAM Postdoctoral Fellowships Program. English review of the MS was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación through project to ILR with reference number PID2019-111039GA-100.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Our protocols for bird capture, handling, and collection of samples were in total compliance with Mexican Law by the Secretaria del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (permit number SGPA/DGVS/12889/13 from Dirección General de Vida Silvestre Mexico).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salaberria, C., Chávez-Zichinelli, C.A., López-Rull, I. et al. Physiological status of House Sparrows (Passer domesticus) along an ozone pollution gradient. Ecotoxicology 32, 261–272 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-023-02632-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-023-02632-z