Abstract

Behaviour links physiological function with ecological processes and can be very sensitive towards environmental stimuli and chemical exposure. As such, behavioural indicators of toxicity are well suited for assessing impacts of pesticides at sublethal concentrations found in the environment. Recent developments in video-tracking technologies offer the possibility of quantifying behavioural patterns, particularly locomotion, which in general has not been studied and understood very well for aquatic macroinvertebrates to date. In this study, we aim to determine the potential effects of exposure to two neurotoxic pesticides with different modes of action at different concentrations (chlorpyrifos and imidacloprid) on the locomotion behaviour of the water louse Asellus aquaticus. We compare the effects of the different exposure regimes on the behaviour of Asellus with the effects that the presence of food and shelter exhibit to estimate the ecological relevance of behavioural changes. We found that sublethal pesticide exposure reduced dispersal distances compared to controls, whereby exposure to chlorpyrifos affected not only animal activity but also step lengths while imidacloprid only slightly affected step lengths. The presence of natural cues such as food or shelter induced only minor changes in behaviour, which hardly translated to changes in dispersal potential. These findings illustrate that behaviour can serve as a sensitive endpoint in toxicity assessments. However, under natural conditions, depending on the exposure concentration, the actual impacts might be outweighed by environmental conditions that an organism is subjected to. It is, therefore, of importance that the assessment of toxicity on behaviour is done under relevant environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Arthropod populations form an integral part of freshwater ecosystems and are, as such, often exposed to chemical and physical disturbances such as nutrients, pollutants, habitat destruction and flow alterations (Dudgeon et al. 2006). In agro-ecosystems, pesticides used for plant protection in particular can enter surface waters through spray drift, run off, and draining, and affect non-target animal populations. Hence, environmental risk assessments are required for pesticides to minimize undesired side effects. Standard tests comprise a battery of mortality, immobilization and reproduction studies on single species in the lower tiers of the assessment process. In the higher tiers, micro- and mesocosms may be employed to evaluate ecological community responses to different exposure concentrations (Brock et al. 2006).

To improve the determination of ecologically relevant risk levels, behavioural endpoints are increasingly investigated in ecotoxicological studies (Rodrigues et al. 2016). They have been shown to be relevant and useful in acute and chronic environmental risk assessments because they link physiological functions with ecological processes. Behavioural endpoints are also very sensitive towards environmental stimuli and chemical exposure (Dell’Omo 2002), and several studies assessing the environmental risks of pesticides reported behavioural effects at concentrations significantly below those causing mortality (for examples see Böttger et al. 2013; Agatz et al. 2014). Locomotor behaviour is particularly vital to animal life as it facilitates feeding, predator avoidance, reproduction, or migration, and thus may link the effects of individual stress to the population level (Bayley et al. 1997). This type of behaviour can be studied easily via video tracking (Augusiak and Van den Brink 2015; Rodrigues et al. 2016).

In aquatic environments, relocating macroinvertebrates are likely to encounter contaminated stretches with residue concentrations of pesticides. Depending on the mode of action and concentration of the encountered pesticide, travelling animals may be affected and their movement behaviour may be likely to change under such conditions. Especially neurotoxic substances might adversely affect orientation and activity. The observed alterations in activity, furthermore, correlated with the measured contamination gradient. Baatrup and Bayley (1993) showed that cypermethrin exposure disrupted the general movement pattern and activity of the Wolf Spider Pardosa amentata. However, studies on the behavioural effect of toxicants on aquatic crustaceans, so far mainly focused on feeding responses (Böttger et al. 2013; Agatz et al. 2014), induction of drift (Beketov and Liess 2008), breathing activity, and immobilization (for example Rubach et al. 2011). Fewer studies attempted quantification of more complex behaviour such as precopulatory mate guarding (Blockwell et al. 1998) or predator–prey interactions (Brooks et al. 2009) after sublethal pesticide exposure. To estimate the impact of chemical exposure on arthropod populations in an ecologically more meaningful way, ecological effect models are increasingly often applied to integrate different habitat, species, and exposure related information to assess population recovery timeframes (Galic et al. 2013; Focks et al. 2014). Accounting for immigrating and emigrating individuals is essential to improve the mechanistic understanding derived from such modelling studies (Focks et al. 2014; Hommen et al. 2015).

With the present study, we present a method to test the effects of chemical exposure on macroinvertebrate movement, and to improve the understanding of the potential effects of exposure to neurotoxic pesticides, in this case chlorpyrifos and imidacloprid, on the water louse Asellus aquaticus. To establish a broader knowledge of the background levels and variance of the movement responses we included observations of non-exposed specimens under environmentally relevant scenarios such as the presence or absence of food and shelter items.

Imidacloprid is a selective and systemic insecticide belonging to the group of neonicotinoids that agonistically affect nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) of insects (Matsuda et al. 2001). Chlorpyrifos, on the other hand, is an organophosphate insecticide that inhibits acetylcholine esterase, which is essential to nerve function in insects, humans, and other animals (Pope 2010), thus acting as a broad-spectrum agent (Song et al. 1997). Exposure to either substance, however, can eventually cause paralysis and death. We aimed to test whether the differences in mode of action would lead to different effects on the locomotion behaviour and whether the responses are concentration-dependent.

A. aquaticus is widely distributed throughout Europe, and is relatively sensitive to insecticides (Wogram and Liess 2001). As consumers at an intermediate trophic level, they also fulfil an important role in the nutrient cycling of aquatic ecosystems (Wallace and Webster 1996). Their population recovery processes are limited since the species has a fully aquatic life-cycle with virtually no possibility to reoccupy exposed patches by air. Recovery, hence, depends mostly on the intrinsic reproduction potential and dispersal of individuals within a water body from uncontaminated patches towards exposed ones. This species also appeared to be easily studied using automated video tracking (Augusiak and Van den Brink 2015).

Materials and methods

Test species

Adult A. aquaticus were collected from a non-contaminated pond (Duno pond, Doorwerth, The Netherlands) with sweeping nets, and organisms larger than approximately 5 mm were transferred to the laboratory. The specimens were kept in a 30 L aquarium in a climate-controlled room at 18 °C and a 10:14 light:dark cycle. Prior to the experiments, the organisms were acclimatised to copper-free water over 1 week by a sequential diluting process of the original pond water with copper-free water. Dried poplar leaves were provided as food source ad libitum and aeration was constantly supplied. Individuals for the experiments were chosen randomly from this stock (mean body length ± standard deviation: 6.4 mm ± 0.66).

Experimental setup

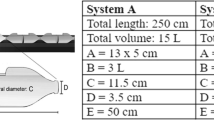

The movement observations were performed in a climate-controlled room at 20 °C. The test setup consisted of a camera mounted above an aquarium of 1 m2, which was filled with a 0.5 cm layer of quartz sand and 10 cm of copper free tap water. Before the observations, individual specimens were marked with rectangular paper snippets of approximately 2 × 2 mm, left for 1 h to recover from the marking procedure, and introduced into the aquarium. Small droplets of cyanoacrylate (Pattex, Gold Gel) were used to fix the marker to the backs of the Asellus. After introduction into the aquarium and 30 min acclimation time, animal movements were recorded for 1 h and the tracks statistically evaluated to determine movement related parameters. We used a digital single-lens reflex camera (EOS 1100D, Canon) for the recordings, which was connected to a computer. Four of such aquarium-camera combinations were installed in parallel within a water bath that maintained constant temperatures. See Augusiak and Van den Brink (2015) for further details about the used methodology.

Water temperature, pH and dissolved oxygen were measured twice every day to ascertain stable conditions throughout the experimental period. All experiments were carried out at a water temperature of 20 ± 0.8 °C, an average pH of 7.6 ± 0.3 (measured with electrode pH323, WTW Germany) and an average dissolved oxygen level of 8.6 ± 0.3 mg/L (measured with oximeter Oxi330 equipped with sensor CellOx 325, WTW Germany).

Test chemicals: application, sampling, and analysis

Exposure concentrations were derived from toxicity tests performed prior to the behavioural study (see Online Resource 1 for details). Solutions of chlorpyrifos were prepared by spiking copper-free water with an aqueous stock solution of chlorpyrifos (480 g/L) to reach exposure concentrations of 0, 0.6 and 1.5 μg/L (48 h-EC50 = 3.2 μg/L, 48 h-EC10 = 2.7 μg/L, Online Resource 1).

Water samples from the controls and exposure vessels were taken at the start and after 48 h of exposure to confirm concentrations. In the beginning, 200 mL samples were taken from the spiked batch volume; at the end, 200 mL per exposure vessel were sampled. Chlorpyrifos was measured by liquid–liquid extraction with 20 mL n-hexane followed by gas chromatography coupled with electron capture detection (GC-ECD). The specifications for the sample analysis via GC-ECD were in accordance with the study by Rubach et al. (2011).

Dosing solutions of imidacloprid were prepared by mixing a soluble formulation containing 200 g imidacloprid/L into copper-free water, yielding an 80 ppm stock solution, which was used to spike the exposure solutions of 0, 37.5 and 75 μg/L (48 h-EC50 = 603 μg/L, 48 h-EC10 = 225 μg/L, Online Resource 1). Water samples from the controls and exposure vessels were taken at the start and after 48 h of exposure to confirm concentrations. For this, samples of approximately 3 mL were transferred into 4 mL glass vials that contained 1 mL acetonitrile. After mixing, the vials were stored at −20 °C prior to analysis. Specifications for the water sample analysis via liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) were analogous to the study by Roessink et al. (2013).

Test conditions

To study the effects of sublethal pesticide exposure on the dispersal behaviour, specimens were exposed to the respective pesticide concentration for 48 h prior to the marking and video observation procedure. After 48 h, the animals were removed from the exposure vessels and transferred into clean, copper-free tap water. Water quality parameters were measured in the beginning and the end of the exposure phase and water samples taken for chemical analysis at the same time. During the chlorpyrifos exposure, the water temperature was 20.1 ± 1.6 °C, the average pH was 6.8 ± 0.8 (measured with electrode pH323, WTW Germany) and the average dissolved oxygen level was 7.9 ± 0.2 mg/L (measured with oximeter Oxi330 equipped with sensor CellOx 325, WTW Germany). During the imidacloprid exposure the water temperature was 20.0 ± 1.4 °C, the average pH 7.8 ± 0.2 and the average dissolved oxygen level was 7.5 ± 1.2 mg/L. Control groups were kept under similar conditions, except that no pesticide was added.

To test the effect of potential food items being present, we cut leaves found in the animals’ native environment into 5 × 5 cm rectangular pieces and hung four such fragments at evenly distributed spots into the water in the arenas. We used simple threads to fix the leaves and adjusted the vertical position in the water phase so that the leaf material was just immersed. Shelter experiments, on the other hand, were conducted with 5 × 10 cm big rectangles of stainless steel mesh wire structures that were placed at six evenly distributed spots in each arena. Control groups were handled similarly, except that no items were added to the arena. All experiments were conducted with two population densities, one and fifty individuals per arena, respectively, and were replicated twenty times each (Augusiak and Van den Brink 2015).

Data analysis

We used the open source software ImageJ (Abramoff et al. 2004) to extract animal tracks from the recorded movies. Tracks within a 10 cm margin of the arena’s walls were dismissed to exclude potential bias due to edge behaviour (Creed and Miller 1990). The obtained time series of (x, y)-coordinates of the animals’ positions were analysed using the R software (R Core Team 2013) and the package “adehabitatLT” (Calenge 2006).

We defined relocations of less than 1 mm as resting moments (Augusiak and Van den Brink 2015), and calculated resting time per individual as the percentage time that the respective individual spent not moving. During periods of activity, behaviour was further characterized by step lengths and turning angles. Step length is defined as the distance covered per time interval, whereas angles between successive moves were measured as deviation from straight locomotion in degrees (±180°) (see Fig. 1a for a schematic representation of the path components). Since these metrics depend on the physical or temporal scale at which they are measured, we chose to further calculate the fractal dimension of each individual’s path. The fractal dimension is a measure of a path’s tortuosity and quantifies an object’s ability to cover the Euclidian space through which it navigates scale-independently (Seuront et al. 2004b). The parameter values range between D = 1 (straight line) to D = 2 (Brownian motion). We used the Fractal Mean Estimator contained in the Fractal software made available by Nams (1996) to calculate the fractal dimension for each path. If multiple paths were obtained for one individual, a mean value was estimated. The software makes use of the divider method (Mandelbrot 1967) and calculates the trajectory length (L) over a range of divider sizes (δ; see Fig. 1b for a schematic illustration) such that

where k is constant, and D the fractal dimension of the trajectory. The fractal dimension can be calculated from a subsequent regression of log(L) as a function of log(δ). We used 200 divider sizes (δ) ranging from approximately half of a species’ body size (Asellus: 0.25 cm) to the observation scale of 100 cm. Movement tracks shorter than 5 relocation points were excluded from the estimation of fractal dimension values to facilitate a robust regression. For consistency among compared parameters, we limited the remaining data analysis to the same range.

a Illustration of the components of a movement path. Solid lines represent the distance Di travelled per time interval (step length). The dashed lines indicate the turning angle (θ) as the deviation from straight-line locomotion measured in degrees (±180°). b Schematic of the divider method. Two steps of the analysis are shown, using two different divider lengths δ (Adapted from Seuront et al. 2004a, b)

The assumption of normality was violated for all variables, except a transformed version of the fractal dimension [log(D-1) transformed], restricting us to mostly non-parametric tests to assess differences between experimental conditions. Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests were applied to test for pairwise differences of resting times and step lengths between treatments, Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for comparing more than two treatments. To determine differences between fractal dimension values, we used the Welch’s t test, or in case of comparing more than two treatments, ANOVA. Standard methods of circular statistics were used to analyse the turning angles. Since the angular distributions exhibited varying concentration parameters κ, we used the non-parametric Watson–Wheeler test to compare treatment effects (Batschelet 1981). Significances were assessed at a 95 % confidence level.

The paths recorded under different experimental conditions were further analysed for deviances with a correlated random walk (CRW) model following the steps laid out in Turchin (1998). This type of model is suitable for evaluating paths in homogeneous environments and can be used to estimate the population dispersal rate within the respective substrate (Turchin 1998). For an analysis of movement paths according to the CRW model framework, a series of statistical approaches needs to be applied to test whether model assumptions are met.

The primary assumption in CRW models is that the organisms exhibit some degree of directional persistence, i.e. the stronger the directional persistence, the faster the population is assumed to spread. This can be checked visually via the frequency distribution of observed turning angles. CRW models furthermore assume that step lengths and turning angles within a path are not serially correlated (Turchin 1998). Such correlations can influence the model output and need to be interpreted accordingly (Turchin 1998; Westerberg et al. 2008; Dray et al. 2010). Auto-correlation for step-length and turning angles was estimated according to the procedures defined by Dray et al. (2010). The correlation between the magnitude of turning angles and step length was estimated using Spearman’s correlation.

For verifying the applicability of the CRW formulation, net-squared displacements (R 2n ) were calculated and comparisons made between estimated (theoretical) and observed (actual) values. Observed net-squared displacements were calculated as the squared distance between each location in an individual’s track and the individual’s original location. Directional information thereby is removed by using the square of the distances. According to the CRW framework, R 2n can be estimated and extrapolated as follows:

where L1 is the mean move length (cm), L2 is the mean squared move length (cm2), n is the number of consecutive moves, and c is the mean cosine of turning angles (Kareiva and Shigesada 1983; Turchin 1998). The 95 % confidence interval for the estimated R 2n was constructed following a procedure described by Turchin (1998).

Results

Due to excluding short tracks and tracks within the outer 10 cm margin of the aquaria from the data analysis, we did not obtain tracking information for all time points. The number of data points analysed for each test regime along with the number of paths and their average duration are summarised in Table 1. Furthermore, Table 1 lists the intended and measured concentrations of the two studied pesticides. The achieved chlorpyrifos concentrations were approximately 40 % below the intended levels at the start of the exposure phase. During the course of the exposure the concentrations dropped due to evaporation, chemical degradation, and sorption processes. However, the concentration difference remained at a factor of approximately 2 between the higher and the lower concentration treatments, indicating that observed changes in behaviour were still comparable among the different exposures. Achieved imidacloprid concentrations, on the other hand, were slightly above the intended levels, with concentrations decreasing less strongly as in the case of chlorpyrifos.

Observed movement and dispersal

In Fig. 2 the relationship between the observed net-squared displacements (R 2n ) of A. aquaticus under different testing conditions and the number of consecutive steps they have made is represented with dashed lines. Net-squared displacement describes the ability of an organism to disperse, i.e. the smaller its value the closer an individual is to its original location. An individual’s R 2n over time is influenced by the combination of step lengths and turning angles it uses. The more active an animal is and the longer and more directed its subsequent steps are, the faster it will move away from its original location.

Relationship between the mean net-squared displacement (R 2n ; cm2) and the number of consecutive moves made by A. aquaticus under different experimental conditions. Doted lines: observed mean net-squared displacement obtained by averaging over 20 observed individuals; dashed lines: estimated net-squared displacement obtained by applying the observed average move distances and turning angles; solid: 95 % confidence interval of the estimated net-squared displacement; red stands for the single-Asellus studies and black for the 50-Asellus studies (Color figure online)

Pesticide exposure

Observed net-squared displacements were reduced by pesticide exposure compared to the respective controls (Fig. 2a–e). Higher exposure concentrations thereby caused stronger decreases in R 2n for both substances, except for the application of the higher chlorpyrifos dosage in the higher density setup. That treatment also changed the observed pattern of single individuals dispersing farther than their counterparts in a group (Fig. 2b). Compared to the controls, chlorpyrifos exposure increased resting times and decreased step lengths more than imidacloprid exposure did. The standard deviations of either parameter also increased but were, irrespective of the substance, concentration, or population density, overall in a more similar range than the mean values (Table 1). The control group exhibited slightly bigger average turning angles with lower variability than the exposed groups did, which however hardly affected the fractal dimension of the analysed paths. Resting times were affected significantly for all single-specimen observations, while step lengths were affected significantly or marginally significantly for both single- and 50-specimens observations (Table 2). Chlorpyrifos exposure had an overall statistically more significant effect on those parameters than imidacloprid exposure had. Turning angles and fractal dimension were statistically less affected by either exposure (Table 2).

Environmental stimuli

Observed R 2n were more similar to each other in the food, shelter, and their respective control tests (Fig. 2f–h) than was the case for the pesticide tests. The presence of food items slightly decreased R 2n in the single individual setup, whereas the presence of shelter items did not cause any observable changes. The biggest effect on observed R 2n in these three setups was caused by population density. Higher population densities led to decreased R 2n (Fig. 2f–h). Resting times increased compared to the controls when shelter or food items were introduced to the arena (Table 2). In the presence of shelter, resting times were equal among the different population densities. When food items were present, the single- and 50-individual specimen maintained the approximate 10 % difference that we also found in the control groups. Average step lengths remained virtually the same in the presence of food items, and were slightly lower, although not significant, when shelter items were available. Amongst the different treatments, the observed individuals increased resting times and decreased average step lengths when they were with conspecifics compared to the respective single-specimen setups, probably due to the increased “traffic”. Average turning angles increased in the presence of food items, while the presence of shelter items left this parameter unaffected. The fractal dimension decreased slightly more when shelter items were available than when food items were present (Table 1). The variability of these parameters was less affected by either treatment than observed in the pesticide exposure experiments, and no statistical indication of treatment effects could be detected. These changes indicate that the observed Asellus started searching for food when food items were present, while the presence of shelter provided structures for resting.

Food availability before the experiments had the overall biggest influence on the observed movement behaviour. The pesticide control groups did not receive food for 48 h prior to the experiment. The control groups for testing the influence of external factors, on the other hand, had access to food until shortly before the recording. The lack of food caused an increase in observed net-squared displacement (Fig. 2a, f), which can be explained by a statistically significant reduced resting time and increased step lengths (Table 1). While the turning angle range hardly changed, the fractal dimension decreased slightly, indicating that the observed animals changed to overall more linear movements. Additionally, the differences in resting times and step lengths found between the single- and 50-specimen setups disappeared when the individuals were starved (Table 1).

Correlation and autocorrelation

Most observed individuals in the various treatments displayed directional persistence forwards (Table 2), meeting the central assumption made under the CRW framework. Turning angles were also significant positively auto-correlated at lag 1 in most cases, and remained significant for several lags (see Online Resource 2 for detailed results), representing a tendency to make sequential turns in the same direction. Furthermore, auto-correlations in step lengths were significant positive at lag 1 for almost all individuals, and remained significant for a number of lags (Online Resource 2), which suggests that most individuals maintained similar walking speeds for a number of steps. In all treatments, step lengths and turning angles were significant negatively correlated (Table 2), i.e. larger changes in direction were performed only when the individuals slowed down, and average angles decreased with increasing walking speed.

Dispersal estimates

Figure 2, furthermore, compares the observed and estimated net-squared displacements (R 2n ) of A. aquaticus under different testing conditions. The CRW model overpredicts observed R 2n in cases where the observed path is more tortuous than assumed by the model. In cases of underestimation, the observed path is straighter or the animal activity lower than expected.

Generally, we found that estimated R 2n exceeded the observed values for the non-pesticide, single-specimen observations, while observed R 2n were mostly underestimated after pesticide exposure. Exceptions are the lower chlorpyrifos and the starved control treatments. At the higher population density this pattern changes and all observed R 2n exceed the estimated values except for the starved control group (Fig. 2a–e). In the latter case, the model fits the observed pattern better for the non-pesticide treatments during the initial steps compared to the pesticide treatments. However, the CRW models do not provide a good overall fit to the observed displacements (Fig. 2). The closest fits were found for the higher population density when the observed individuals were fed, and when food items were present (Fig. 2g).

Discussion

This study aimed to improve insights into the small-scale movement behaviour of A. aquaticus and to evaluate its potential as endpoint in ecotoxicological studies with aquatic macroinvertebrates. The employed video-tracking method (Augusiak and Van den Brink 2015) allowed the detection of already small changes in the exhibited behaviour, although the high inter-individual variability of the analysed parameters made it difficult to detect statistical significant treatment effects. Our results indicate that the locomotory behaviour and dispersal potential of A. aquaticus were negatively affected by exposure to sublethal concentrations of chlorpyrifos and imidacloprid, while the presence of food or shelter items reduced the dispersal rate less significantly. In most cases, an increased population density lowered dispersal rates further. The observed effects on the small-scale behaviour also affected the displacement extrapolations.

The pesticides were chosen because of their relatively low elimination rates, making it likely that exposed individuals still experience pesticide related effects when placed in clean water that then can be observed. Rubach et al. (2010) report a 95 % depuration time of 16.2 days for chlorpyrifos in A. aquaticus and of 7.5 days for adult Gammarus pulex, a freshwater shrimp species. In the case of imidacloprid, Ashauer et al. (2010) determined a 95 % depuration period of 11.2 days for G. pulex. We assumed a continued causation of damage on the nervous system of A. aquaticus during the experimental time frame also in the case of imidacloprid. First estimations based on acute toxicity data of imidacloprid exposure, yielded a 95 % depuration period of about 4.4 days for Asellus (Focks 2015—personal communication).

The fact that G. pulex exhibits significantly higher sensitivities to both chemicals with regard to mobility and survival indicates that surviving individuals could possess a more efficient elimination pathway compared to Asellus, allowing the conclusion that the internal concentrations in our study should be stable over the period of time of observation. To test whether changes in locomotion are still observable at sublethal levels, we aimed to apply about 50 and 25 %, respectively, of the observed 48 h-EC10 of 2.7 μg/L in the case of chlorpyrifos (Rubach et al. 2011: 48 h-EC10 = 3.3 μg/L). Due to a wider range of reported ECx values, we opted for a slightly higher safety factor for imidacloprid and chose to continue with about 30 and 15 %, respectively, of the observed 48 h-EC10 value of 225 μg/L (geometric mean of studies reported by Roessink et al. (2013) and Van den Brink et al. (2015): 48 h-EC10 = 54 μg/L). The applied concentrations are also likely to occur in the environment. Concentrations of up to 10.8 μg/L of chlorpyrifos were detected in freshwater habitats throughout the past decade (Marino and Ronco 2005; Ensminger et al. 2013), while imidacloprid has been found at concentrations of up to 320 μg/L (Van Dijk et al. 2013; Ensminger et al. 2013).

In natural environments, the dispersal and local recruitment of aquatic macroinvertebrates is strongly driven by the availability of food, shelter, and population density (Holyoak et al. 2008). Food items may release chemicals during the degradation process, which then can be sensed by an organism equipped with the respective sensing systems (Collin and Marshall 2003). This can subsequently cause an alteration in the organism’s searching behaviour, for example a switch from long, straight moves to a Brownian pattern for local searching together with a change of activity (Collin and Marshall 2003). Similarly, a lack of food may drive animals away from their current location to search for new resources. Shelter, on the other hand, can impact overall movement by providing protection from high temperatures, light, or predators (Obermüller et al. 2007). However, there is a lack of understanding to which degree the presence of food or shelter items can influence the movement and searching behaviour of aquatic invertebrates, or how it may additionally be driven by population density, either by compensating for interspecies competition or improving mating chances (Smith et al. 2008; Delgado et al. 2013).

Understanding the innate nature of movement behaviour, and to which degree different factors influence it, can help extrapolating small-scale observations to gain an impression on the ecological consequences of chemical or physical disturbances (Getz and Saltz 2008). In Table 3, we summarize a number of studies aiming to highlight the influences of chemical exposure or naturally occurring drivers, such as predator cues, on the movement behaviour of aquatic macro invertebrates. We found that most published studies on aquatic invertebrates either focused on environmental cues or chemical exposure, while none related the extent of behavioural changes under sublethal exposure conditions to the innate behavioural range to draw conclusions about potential ecological impact. Observational studies that do investigate such relationships usually use food consumption rates or preferences as endpoint instead of movement (for examples see De Lange et al. 2006b; Agatz et al. 2014). The study by (Rodrigues et al. 2016) forms a rare exception, where the effects of sublethal exposure of freshwater planarians to chlorantraniliprole are investigated through observing changes in feeding behaviour and locomotion.

The strong reductions in observed dispersal distances after pesticide exposure were mostly caused by decreased step lengths and increased resting times, which agrees with previous reports of hypoactivity caused by both substances (Rice et al. 1997; Suchail et al. 2001). Step lengths were significantly reduced by all pesticide treatments, while resting time was more affected by exposure to chlorpyrifos than to imidacloprid. The turning behaviour, i.e. directionality, was not significantly different from that observed in the controls after pesticide exposure, although the variability was higher after exposure (Table 2). These effects are in accordance with the modes of action of the used insecticides. Both substances disturb neural signal regulation to a degree that neurological activity of nerves remains lastingly stimulated, which eventually leads to muscle spasms and paralysis. Chlorpyrifos does so by inactivating the enzyme that hydrolyses acetylcholine, and imidacloprid by activating nACh receptor. The more pronounced effects we found in the case of chlorpyrifos exposure, i.e. the increase in resting time coupled with a decrease in average step length, might be associated with the irreversibility of the enzyme activation, while the nAChR stimulation through imidacloprid is reversible. The reduced step lengths and changes in resting behaviour indicate that muscle malfunction may have set in already at the time of observation. The increased variability of turning angles can be explained by either muscular impairment or additional neurological effects affecting the individuals’ ability to navigate. Based on a study by Azevedo-Pereira et al. (2011) we would speculate to find effects of exposure to chlorpyrifos and imidacloprid to converge further after an extended exposure duration or at increased concentrations. In their study, Azevedo-Pereira et al. (2011) measured AChE activity along with behavioural endpoints after exposure of Chironomus riparius larvae to imidacloprid and found that AChE activity also decreased with increasing concentration after 96 h of exposure onward. The chain of physiological effects of AChE inhibition in Asellus, respectively, would lead to a decrease in overall activity as would be the case after exposure to chlorpyrifos, which directly inhibits AChE activity.

Dose–response or population density related effects were less conclusive in our study. While at the higher concentrations, the higher population densities appear to incite higher activity and slightly larger step lengths, compared to their single-individual equivalents, no such pattern could be identified for the lower concentration treatments. This aspect, together with the high individual variability in behaviour only demonstrates that more research is needed fully understand the sublethal impacts of pesticide exposure on ecologically relevant functions. Eventually, reduced locomotion is likely to interfere with foraging activities as observed by Agatz et al. (2014) in the case of Gammarids. Decreased energy available from feeding and increased energy expenditure for internal repair mechanisms, in turn, may lead to reduced growth and mating (Martin et al. 2012).

In our study, the impact on organisms exposed to imidacloprid may be less drastic compared to chlorpyrifos due to the higher safety factor that we assumed. However, the significance of pesticide exposure becomes clearer, when seen in comparison to the non-pesticide treatments. The presence of food slightly lowered the dispersal potential by affecting orientation moments and variation of turning angles, indicating that the animals were indeed adjusting their searching efficiency. Shelter items on the other hand caused a comparable reduction in dispersal. However, mechanistically it resulted from an effect on activity by reducing step lengths and increasing resting times. The presence of conspecifics affected reorientation less as could probably be expected than that it increased resting times in most cases, respectively reducing overall dispersal. The differences between the fed and starved control groups, however, indicate that the feeding state could potentially change this and reduce the need of shelter availability.

To improve the risk level estimation of chemical exposure on aquatic arthropod populations in an ecologically more meaningful way, ecological effect models can be applied that integrate different habitat, species, and exposure related information to assess population recovery timeframes (Galic et al. 2013; Focks et al. 2014). Accounting for immigrating and emigrating individuals can help to further the mechanistic understanding derived from such modelling studies (Van den Brink et al. 2013; Hommen et al. 2015). The simplified dispersal estimation via the correlated random walk framework as part of this study failed to capture the underlying correlations between turning angles and step lengths, as well as the autocorrelation structures of either of these two parameters. Westerberg et al. 2008 studied the effects of population density and food availability on collembola described a similar phenomenon. The mechanistic links of the Asellus decision making remain to be elaborated for a better model parameterization. Aggregating the step length data may be one of those approaches to eliminate the CRW assumption of non-autocorrelated steps. The high variability of individual behaviour expressions is another factor that complicates simple modelling approaches, although it is an often observed factor in observational studies (Seuront et al. 2004a; Nørum et al. 2010). Hawkes (2009) consequently propose to account explicitly for this variability when designing models of habitat use and dispersal, respectively, an approach that is ignored by the application of simple average values in our study. Integrating findings such as ours into a more complex model can facilitate a better understanding of the complex interactions of chemical exposure and resource availability and their impacts on population recovery times, allowing also for the study of long-term impacts of exposure events.

References

Åbjörnsson K, Wagner BMA, Axelsson A et al (1997) Responses of Acilius sulcatus (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) to chemical cues from perch (Perca fluviatilis). Oecologia 111:166–171. doi:10.1007/s004420050221

Abramoff MD, Magalhães PJ, Ram SJ (2004) Image processing with imageJ. Biophotonics Int 11:36–42

Agatz A, Ashauer R, Brown CD (2014) Imidacloprid perturbs feeding of Gammarus pulex at environmentally relevant concentrations. Environ Toxicol Chem 33:648–653. doi:10.1002/etc.2480

Ashauer R, Caravatti I, Hintermeister A, Escher BI (2010) Bioaccumulation kinetics of organic xenobiotic pollutants in the freshwater invertebrate Gammarus pulex modeled with prediction intervals. Environ Toxicol Chem 29:1625–1636. doi:10.1002/etc.175

Augusiak J, Van den Brink PJ (2015) Studying the movement behavior of benthic macroinvertebrates with automated video tracking. Ecol Evol 5:1563–1575. doi:10.1002/ece3.1425

Azevedo-Pereira HMVS, Lemos MFL, Soares AMVM (2011) Effects of imidacloprid exposure on Chironomus riparius Meigen larvae: linking acetylcholinesterase activity to behaviour. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 74:1210–1215. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.03.018

Baatrup E, Bayley M (1993) Effects of the pyrethroid insecticide cypermethrin on the locomotor activity of the wolf spider Pardosa amentata: quantitative analysis employing computer-automated video tracking. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 26:138–152

Batschelet E (1981) Circular statistics in biology. Academic press, London

Bayley M, Baatrup E, Bjerregaard P (1997) Woodlouse locomotor behavior in the assessment of clean and contaminated field sites. Environ Toxicol Chem 16:2309–2314. doi:10.1002/etc.5620161116

Beketov MA, Liess M (2008) Potential of 11 pesticides to initiate downstream drift of stream macroinvertebrates. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 55:247–253. doi:10.1007/s00244-007-9104-3

Blockwell SJ, Maund SJ, Pascoe D (1998) The acute toxicity of lindane to Hyalella azteca and the development of a sublethal bioassay based on precopulatory guarding behavior. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 35:432–440. doi:10.1007/s002449900399

Böttger R, Feibicke M, Schaller J, Dudel G (2013) Effects of low-dosed imidacloprid pulses on the functional role of the caged amphipod Gammarus roeseli in stream mesocosms. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 93:93–100. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.04.006

Brock TCM, Arts GHP, Maltby L, Van den Brink PJ (2006) Aquatic risks of pesticides, ecological protection goals, and common aims in European Union legislation. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2:20–46. doi:10.1002/ieam.5630020402

Brooks AC, Gaskell PN, Maltby LL (2009) Sublethal effects and predator-prey interactions: implications for ecological risk assessment. Environ Toxicol Chem 28:2449–2457. doi:10.1897/09-108.1

Bundschuh M, Appeltauer A, Dabrunz A, Schulz R (2012) Combined effect of invertebrate predation and sublethal pesticide exposure on the behavior and survival of Asellus aquaticus (Crustacea; Isopoda). Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 63:77–85. doi:10.1007/s00244-011-9743-2

Cailleaud K, Michalec F-G, Forget-Leray J et al (2011) Changes in the swimming behavior of Eurytemora affinis (Copepoda, Calanoida) in response to a sub-lethal exposure to nonylphenols. Aquat Toxicol 102:228–231. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.12.017

Calenge C (2006) The package “adehabitat” for the R software: a tool for the analysis of space and habitat use by animals. Ecol Model 197:516–519. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.03.017

Charoy CP (1995) Modification of the swimming behaviour of Brachionus calyciflorus (Pallas) according to food environment and individual nutritive state. Hydrobiologia 313–314:197–204. doi:10.1007/BF00025951

Charoy CP, Janssen CR (1999) The swimming behaviour of Brachionus calyciflorus (rotifer) under toxic stress. Chemosphere 38:3247–3260. doi:10.1016/S0045-6535(98)00557-8

Charoy CP, Janssen CR, Persoone G, Clément P (1995) The swimming behaviour of Brachionus calyciflorus (rotifer) under toxic stress. I. The use of automated trajectometry for determining sublethal effects of chemicals. Aquat Toxicol 32:271–282. doi:10.1016/0166-445X(94)00098-B

Chen J, Wang Z, Li G, Guo R (2014) The swimming speed alteration of two freshwater rotifers Brachionus calyciflorus and Asplanchna brightwelli under dimethoate stress. Chemosphere 95:256–260. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.08.086

Chevalier J, Harscoët E, Keller M et al (2015) Exploration of Daphnia behavioral effect profiles induced by a broad range of toxicants with different modes of action. Environ Toxicol Chem 34:1760–1769. doi:10.1002/etc.2979

Collin SP, Marshall NJ (2003) Sensory processing in aquatic environments. Springer, New York

Creed RP, Miller JR (1990) Interpreting animal wall-following behavior. Experientia 46:758–761. doi:10.1007/BF01939959

Dawidowicz P, Pijanowska J, Ciechomski K (1990) Vertical migration of Chaoborus larvae is induced by the presence of fish. Limnol Oceanogr 35:1631–1637. doi:10.4319/lo.1990.35.7.1631

De Lange HJ, Noordoven W, Murk AJ et al (2006a) Behavioural responses of Gammarus pulex (Crustacea, Amphipoda) to low concentrations of pharmaceuticals. Aquat Toxicol 78:209–216. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.03.002

De Lange HJ, Sperber V, Peeters ETHM (2006b) Avoidance of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-contaminated by the freshwater invertebrates Gammarus pulex and Asellus aquaticus. Environ Toxicol Chem 25:452–457. doi:10.1897/05-413.1

De Lange HJ, Peeters ETHM, Lürling M (2009) Changes in ventilation and locomotion of Gammarus pulex (Crustacea, Amphipoda) in response to low concentrations of pharmaceuticals. Hum Ecol Risk Assess 15:111–120. doi:10.1080/10807030802615584

Delgado MDM, Penteriani V, Morales JM et al (2013) A statistical framework for inferring the influence of conspecifics on movement behaviour. Methods Ecol Evol. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.12154

Dell’Omo G (2002) Behavioural ecotoxicology. Wiley, New York

Denoël M, Libon S, Kestemont P et al (2013) Effects of a sublethal pesticide exposure on locomotor behavior: a video-tracking analysis in larval amphibians. Chemosphere 90:945–951. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.06.037

Dodson SI, Hanazato T, Gorski PR (1995) Behavioral responses of Daphnia pulex exposed to carbaryl and Chaoborus kairomone. Environ Toxicol Chem 14:43–50. doi:10.1002/etc.5620140106

Dray S, Royer-Carenzi M, Calenge C (2010) The exploratory analysis of autocorrelation in animal-movement studies. Ecol Res 25:673–681. doi:10.1007/s11284-010-0701-7

Dudgeon D, Arthington AH, Gessner MO et al (2006) Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol Rev 81:163–182. doi:10.1017/S1464793105006950

Ensminger MP, Budd R, Kelley KC, Goh KS (2013) Pesticide occurrence and aquatic benchmark exceedances in urban surface waters and sediments in three urban areas of California, USA, 2008–2011. Environ Monit Assess 185:3697–3710. doi:10.1007/s10661-012-2821-8

Faimali M, Garaventa F, Piazza V et al (2006) Swimming speed alteration of larvae of Balanus amphitrite as a behavioural end-point for laboratory toxicological bioassays. Mar Biol 149:87–96. doi:10.1007/s00227-005-0209-9

Ferland-Raymond B, March RE, Metcalfe CD, Murray DL (2010) Prey detection of aquatic predators: assessing the identity of chemical cues eliciting prey behavioral plasticity. Biochem Syst Ecol 38:169–177. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2009.12.035

Focks A, Ter Horst MMS, Van den Berg E et al (2014) Integrating chemical fate and population-level effect models for pesticides at landscape scale: new options for risk assessment. Ecol Model 280:102–116. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2013.09.023

Focks A (2015) Personal communication. Alterra, Wageningen University and Research centre, Wageningen, The Netherlands

Galic N, Hengeveld GM, Van den Brink PJ et al (2013) Persistence of aquatic insects across managed landscapes: effects of landscape permeability on re-colonization and population recovery. Plos One 8:e54584. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054584

Garaventa F, Gambardella C, Di Fino A et al (2010) Swimming speed alteration of Artemia sp. and Brachionus plicatilis as a sub-lethal behavioural end-point for ecotoxicological surveys. Ecotoxicology 19:512–519. doi:10.1007/s10646-010-0461-8

García-de la Parra LM, Bautista-Covarrubias JC, Rivera-de la Rosa N et al (2006) Effects of methamidophos on acetylcholinesterase activity, behavior, and feeding rate of the white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 65:372–380. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.09.001

Getz WM, Saltz D (2008) A framework for generating and analyzing movement paths on ecological landscapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:19066–19071. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801732105

Guo R, Ren X, Ren H (2012) Assessment the toxic effects of dimethoate to rotifer using swimming behavior. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 89:568–571. doi:10.1007/s00128-012-0712-x

Hawkes C (2009) Linking movement behaviour, dispersal and population processes: is individual variation a key? J Anim Ecol 78:894–906. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01534.x

Holyoak M, Casagrandi R, Nathan R et al (2008) Trends and missing parts in the study of movement ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:19060–19065. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800483105

Hommen U, Forbes V, Grimm V et al (2015) How to use mechanistic effect models in environmental risk assessment of pesticides: case studies and recommendations from the SETAC workshop MODELINK. Integr Environ Assess Manag. doi:10.1002/ieam.1704

Janssen CR, Ferrando MD, Persoone G (1994) Ecotoxicological studies with the freshwater rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus. IV. Rotifer behavior as a sensitive and rapid sublethal test criterion. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 28:244–255. doi:10.1006/eesa.1994.1050

Kareiva PM, Shigesada N (1983) Analyzing insect movement as a correlated random walk. Oecologia 56:234–238

Macedo-Sousa JA, Gerhardt A, Brett CMA et al (2008) Behavioural responses of indigenous benthic invertebrates (Echinogammarus meridionalis, Hydropsyche pellucidula and Choroterpes picteti) to a pulse of acid mine drainage: a laboratorial study. Environ Pollut 156:966–973. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2008.05.009

Mandelbrot BB (1967) How long is the coast of britain? statistical self-similarity and fractional dimension. Science 156:636–638. doi:10.1126/science.156.3775.636 (80-)

Marino D, Ronco A (2005) Cypermethrin and chlorpyrifos concentration levels in surface water bodies of the Pampa Ondulada, Argentina. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 75:820–826. doi:10.1007/s00128-005-0824-7

Martin BT, Zimmer EI, Grimm V, Jager T (2012) Dynamic energy budget theory meets individual-based modelling: a generic and accessible implementation. Methods Ecol Evol 3:445–449. doi:10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00168.x

Matsuda K, Buckingham SD, Kleier D et al (2001) Neonicotinoids: insecticides acting on insect nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22:573–580. doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01820-4

Nams VO (1996) The VFractal: a new estimator for fractal dimension of animal movement paths. Landsc Ecol 11:289–297. doi:10.1007/BF02059856

Nørum U, Friberg N, Jensen MR et al (2010) Behavioural changes in three species of freshwater macroinvertebrates exposed to the pyrethroid lambda-cyhalothrin: laboratory and stream microcosm studies. Aquat Toxicol 98:328–335. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.03.004

Nørum U, Frederiksen MAT, Bjerregaard P (2011) Locomotory behaviour in the freshwater amphipod Gammarus pulex exposed to the pyrethroid cypermethrin. Chem Ecol 27:569–577. doi:10.1080/02757540.2011.596831

Obermüller B, Puntarulo S, Abele D (2007) UV-tolerance and instantaneous physiological stress responses of two Antarctic amphipod species Gondogeneia antarctica and Djerboa furcipes during exposure to UV radiation. Mar Environ Res 64:267–285. doi:10.1016/j.marenvres.2007.02.001

Peeters ETHM, De Lange HJ, Lürling M (2009) Variation in the behavior of the amphipod Gammarus pulex. Hum Ecol Risk Assess 15:41–52. doi:10.1080/10807030802615055

Pope CN (2010) Organophosphorus pesticides: do they all have the same mechanism of toxicity? J Toxicol Environ Heal Part B Crit Rev 2:161–181. doi:10.1080/109374099281205

R Core Team (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing

Ren Z, Zha J, Ma M et al (2007) The early warning of aquatic organophosphorus pesticide contamination by on-line monitoring behavioral changes of Daphnia magna. Environ Monit Assess 134:373–383. doi:10.1007/s10661-007-9629-y

Ren Z-M, Li Z-L, Zha J-M et al (2008) The avoidance responses of Daphnia magna to the exposure of organophosphorus pesticides in an on-line biomonitoring system. Environ Model Assess 14:405–410. doi:10.1007/s10666-007-9136-0

Rice PJ, Drewes CD, Klubertanz TM et al (1997) Acute toxicity and behavioral effects of chlorpyrifos, permethrin, phenol, strychnine, and 2,4-dinitrophenol to 30-day-old Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes). Environ Toxicol Chem 16:696–704. doi:10.1002/etc.5620160414

Rodrigues ACM, Henriques JF, Domingues I et al (2016) Behavioural responses of freshwater planarians after short-term exposure to the insecticide chlorantraniliprole. Aquat Toxicol 170:371–376. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.10.018

Roessink I, Merga LB, Zweers HJ, Van den Brink PJ (2013) The neonicotinoid imidacloprid shows high chronic toxicity to mayfly nymphs. Environ Toxicol Chem 32:1096–1100. doi:10.1002/etc.2201

Rubach MN, Ashauer R, Maund SJ et al (2010) Toxicokinetic variation in 15 freshwater arthropod species exposed to the insecticide chlorpyrifos. Environ Toxicol Chem 29:2225–2234. doi:10.1002/etc.273

Rubach MN, Crum SJH, Van den Brink PJ (2011) Variability in the dynamics of mortality and immobility responses of freshwater arthropods exposed to chlorpyrifos. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 60:708–721. doi:10.1007/s00244-010-9582-6

Seuront L, Hwang J-S, Tseng L-C et al (2004a) Individual variability in the swimming behavior of the sub-tropical copepod Oncaea venusta (Copepoda: Poecilostomatoida). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 283:199–217. doi:10.3354/meps283199

Seuront L, Schmitt FG, Brewer MC et al (2004b) From random walk to multifractal random walk in zooplankton swimming behavior. Zool Stud 43:498–510

Smith MJ, Sherratt JA, Lambin X (2008) The effects of density-dependent dispersal on the spatiotemporal dynamics of cyclic populations. J Theor Biol 254:264–274

Song MY, Stark JD, Brown JJ (1997) Comparative toxicity of four insecticides, including imidacloprid and tebufenozide, to four aquatic arthropods. Environ Toxicol Chem 16:2494–2500. doi:10.1002/etc.5620161209

Suchail S, Guez D, Belzunces LP (2001) Discrepancy between acute and chronic toxicity induced by imidacloprid and its metabolites in Apis mellifera. Environ Toxicol Chem 20:2482–2486

Turchin P (1998) Quantitative analysis of movement. Sinauer, Sunderland

Van den Brink PJ, Baird DJ, Baveco HJM, Focks A (2013) The use of traits-based approaches and eco(toxico)logical models to advance the ecological risk assessment framework for chemicals. Integr Environ Assess Manag 9:e47–e57. doi:10.1002/ieam.1443

Van den Brink PJ, Van Smeden JM, Bekele RS et al (2015) Acute and chronic toxicity of neonicotinoids to nymphs of a mayfly species and some notes on seasonal differences. Environ Toxicol Chem. doi:10.1002/etc.3152

Van Dijk TC, Van Staalduinen MA, Van der Sluijs JP (2013) Macro-invertebrate decline in surface water polluted with imidacloprid. Plos One 8:e62374. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062374

Wallace JB, Webster JR (1996) The role of macroinvertebrates in stream ecosystem function. Annu Rev Entomol 41:115–139

Westerberg L, Lindström T, Nilsson E, Wennergren U (2008) The effect on dispersal from complex correlations in small-scale movement. Ecol Model 213:263–272. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.12.011

Wogram J, Liess M (2001) Rank ordering of macroinvertebrate species sensitivityto toxic compounds by comparison with that of Daphnia magna. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 67:360–367. doi:10.1007/s001280133

Zein MA, McElmurry SP, Kashian DR et al (2014) Optical bioassay for measuring sublethal toxicity of insecticides in Daphnia pulex. Environ Toxicol 33:144–151. doi:10.1002/etc.2404

Acknowledgments

We thank Ivo Roessink and Theo Brock for their support in the realisation of the lab experiments. For assistance with R scripts, we thank Andrea Kölzsch. Furthermore, we would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on a previous version of this manuscript that helped to greatly improve it. This work was financially supported by the European Union under the 7th Framework Programme (Project acronym CREAM, Contract Number PITN-GA-2009-238148).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or vertebrate animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10646_2016_1686_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Online Resource 1: Results of a 48 h toxicity test for determining exposure concentrations of imidacloprid and chlorpyrifos in this study. (PDF 42 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Augusiak, J., Van den Brink, P.J. The influence of insecticide exposure and environmental stimuli on the movement behaviour and dispersal of a freshwater isopod. Ecotoxicology 25, 1338–1352 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-016-1686-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-016-1686-y