Abstract

Within an early childhood setting strong collaborative partnerships between the service and the family are critical to the success of a child’s development and learning. Collaborative interactions with families are considered indicators of quality within early childhood services. Whilst the value and importance of collaborative partnerships are widely agreed upon, the plethora of terms utilised to describe collaborative partnerships, and the multitude of models for its enactment have muddied the waters for successful interpretation and application in practice. This paper employs metaphor as a way of creating conceptual clarity of the complex issues surfaced in the literature related to collaborative partnerships and their intended implementation in curriculum and policy, and what practices occur in services globally. Findings highlight a mismatch between discourse and practice and elucidate the missed opportunities for collaborative partnerships towards improving service quality. Insights identified in this paper are relevant to the early childhood sector, highlighting a call for further clarity and interpretation of the term and mechanisms of quality collaborative partnership to inform practices in the field. This paper suggests new ways of thinking that rupture taken for granted viewpoints, offering the metaphor of a tandem bicycle to reflect the collaborative partnership between educators and families. This article provides a powerful provocation for the early childhood field to encourage reflection and refinement to existing conceptualisations of family-educator relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Collaborative partnerships in early childhood education and care (ECEC) remain a critical topic for developing insights for all EC stakeholders including researchers, practitioners, families, and community partners alike with the literature surrounding the topic, quite complex. Pivotal for the positive outcomes for children, families, and early childhood services the value of collaborative partnerships are extensively addressed in key national and international curriculum documents and research Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] (2021). These global perspectives on collaborative partnerships illuminate a broad diversity in the way educators and families engage and develop relationships (Kambouri et al., 2021; O’Connor et al., 2018).

Significant research exists on notions of family engagement, involvement, participation, and collaboration (Kambouri et al., 2021), where roles, responsibilities, and capacities of educators and families are interwoven (Dunst et al., 2019; O’Connor et al., 2018; Rouse & O’Brien, 2017). Within ECEC interconnected relationships between families and educators, their pre-existing beliefs, and expectations, as well as environmental and contextual considerations, culminate to impact stakeholder experiences (Brown, 2019; Gross et al., 2018). With such expansive and varied terminology being utilised broadly, researchers including Hadley and Rouse (2018) and Rouse and O’Brien (2017) claim the ambiguity of collaborative partnerships, and the components that enable them, has led to a mismatch between policy and practices in the field

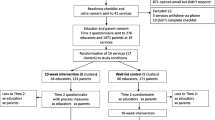

Motivated by this lack of clarity, Author One engaged in a literature review over a twelve-month period (2021–2022) where the focus was on investigating the multifaceted nature of the relationship between educator and family in ECEC settings. Database searches were conducted utilising key words including ‘collaborative partnerships’, ‘parent or family engagement’, ‘family-educator partnerships’ that helped reveal an in-depth scholarly understanding and appreciation on this topic. Results of the literature search were narrowed, based on currency, to include peer reviewed publications since the year 2000, with the exception of historically seminal works. Focused the conceptualisation and application of collaborative partnerships, 91 publications contributed to the review. The connection between international ECEC frameworks, their articulation of stakeholder positioning, and evidence of practices in the field were revealed from the extensive review of the literature.

A further dilemma surfaced in the complexities that emerged from the process of synthesising diverse perspectives on collaborative partnerships. In seeking clarity whilst deep in the literature, the first author utilised critical colleagues (Author Two and Three) in proposing the notion of metaphor as a vehicle to make sense of and explain concepts and connections arising in the literature. This process included questions being posed, leading to further metacognition and deep reflection, resulting in the emergence of the tandem bicycle metaphor.

The use of metaphor can be a way of conceptualising and presenting literature. This paper shares insights, where metaphor is used to help the reader make sense of the synthesised literature and the tensions within. Metaphor is seen by the authors as particularly useful to think through complexities or dilemmas that are not easily explained (Southall, 2013). A metaphor of a tandem bicycle is used to reflect the collaborative partnership between educators and families and to pull together the key points raised in the literature regarding force, tension, unequal weighting in decision making and commitment to shared goals and reorganise patterns of thinking. Beginning by navigating a definition of collaborative partnerships, the paper then orientates the discussion within international education documentation. The authors introduce the use of metaphor to help to make sense of the complexities brought to light in the literature. Finally, they highlight opportunities for practitioners in the field to reframe their considerations of collaborative partnerships.

Resonating across the globe is the importance of collaborative partnerships, both within the literature, as well as in EC practice. The OECD (2021) list the engagement of EC services with families and communities to be as significant an indicator of quality as low child to educator ratios, and qualifications of educator. Research from the United Kingdom and North America support this correlation between quality ECEC services (Cottle & Alexander, 2014) and outcomes for children (Hartman, 2018). Significantly reinforced in studies from New Zealand and Europe (Beaumont-Bates, 2017; Hujala et al., 2009) is a clear from the consensus that collaborative partnerships are not only valued but imperative to outcomes for children, relationships between stakeholders and service quality.

A key point to emerge from a review of the literature was the interconnectedness of collaborative partnerships and improvement processes, where the engagement of stakeholders towards a common goal seeks to improve outcomes (Stone, 2015) and quality practices (Choi & Choi, 2012). International research from the United States and Africa surfaced the process of collaboration requiring the act of working together (Choi & Choi, 2012), harnessing the ability to achieve more as a collective than is possible to accomplish alone (Stone, 2015). Similarly, further American research suggests through these efforts there emerges a co-creation of supportive environments that meet the needs of the collective, invested in a common goal that combines the interests of all stakeholders (Roussos & Fawcett, 2000). Insights from the literature highlight that this approach works to build the capacity of each stakeholder, as a biproduct of the journey towards quality improvement (Provan et al., 2005; Stone, 2015). Facilitated by this understanding we define collaborative partnerships as ‘the connection of stakeholders who endeavour to work collectively to improve outcomes of a common goal’.

Consistent with this narrative are key findings from the recent OECD ‘Starting Strong VI’ report ‘The Early Childhood Education and Care Policy Review: Quality beyond Regulations’ that explored meaningful interactions between stakeholders across 120 ECEC settings, 26 countries, and 56 associated curriculum frameworks. The report highlights the diverse approaches to ECEC worldwide, as well as the complexities involved in analysing and comparing these (Nesbitt & Farran, 2021). Interestingly, underscored across international curriculum and frameworks is recognition of the importance of family involvement in ECEC services (OECD, 2021). Further, the report (OECD, 2021) highlights significant variation in how family engagement is referred to, with each country’s underpinning values and beliefs around the role of families in ECEC being articulated through the underlying pedagogical approaches in their associated curriculums.

As well, an international comparative study by Vlasov and Hujala (2017) considers the historical, economic, and socio-cultural influences on partnership roles across America, Russia, and Finland. A consistent theme within each of these contexts is the valuing of family-educator relationships in the learning environment, yet these understandings and relationships are nuanced and contextual within each setting. This contextual boundedness is also echoed by the dominant discourses of each region’s educational curriculum. Interestingly, the diversity of interpretations of family-educator relationships, manifested in associated curriculum frameworks also emerges as a key finding in the OECD report (2021) with these curricula recognised as an important tool in guiding educators, services, and families regarding ways in which to engage and cooperate that then translate into successful collaborative partnerships and quality standards (Boyd & Garvis, 2021).

An exploration of international research and ECEC frameworks provides further insights into interpretations and understandings of collaborative partnerships. For example, in Belgium, the Measuring and Monitoring Quality in Child Care for Babies and Toddlers is underpinned by a priority principal of partnership (Measuring and Monitoring Quality in Childcare for Babies and Toddlers, 2014). Similarly, the International Step by Step Association (ISSA) Quality Framework for birth to three services in the Netherlands places families as a primary source of influence and responsibility, where inclusion, diversity, and democracy together with respectful, reciprocal partnerships is at the heart of their focus on engagements between educators and families (ISSA, 2016). Finally, Ireland’s Aistear EC Curriculum Framework (NCCA, 2009) is intentional in reinforcing the focus of building partnerships with families, and Jamaica’s Early Childhood Curriculum Guide utilise terminology of involving families (Davies, 2008).

As the delivery modes and models of ECEC continue to diversify, so to do the expectations on educators and families to collaborate with a collective focus on positive outcomes for children. However, alongside this goal is an ongoing confusion, in many cases, regarding the roles and responsibilities of families and educators. Researcher One could see this materialise in the conceptualisation of a metaphor to explain this tension. In these various ECEC service models, a range of factors influence how family-educator interactions are understood and enacted (Ali et al., 2022; Cottle & Alexander, 2014; Cutshaw et al., 2022). For example, increasingly, families may experience an engagement model where they are seen as seen as consumers in a marketised provision of a service, whereas at other times they may be seen as active participants, and encouraged alongside the service to have input into shared decision making of goals for their child (Fenech et al., 2019; Vlasov & Hujala, 2017).

Emerging from the international literature is the notion that once a family engages in an ECEC service a dichotomous relationship appears. In an Australian study, Fenech et al. (2019) found the family are considered consumers with expectations, whilst at the same time being knowledgeable experts on their child and encouraged to share in the driving of goals and planning. In Sweden, an increased focus of families collaborating with educators saw a reenvisaging of active family engagements that improved home-school connections, but not without considerable negotiation of roles and expectations (Markström & Simonsson, 2017), The successful development of these authentic, trusting relationships between families and educators has the potential to improve ECEC quality outcomes (Vuorinen, 2020). Absent in much of the collaborative partnership literature is mention of family voice or input (Lang et al., 2016; Vuorinen, 2020) with significant gaps in research on the building of bonds between family and educator (Vuorinen, 2020). Vlasov and Hujala (2017) caution that if not carefully negotiated, power imbalances have the potential to threaten to weaken the relationship and connections between educator and family. Notably visible throughout the literature is the struggle for clarity of role accountabilities and expectations for and of the family and the educator in collaborative partnerships.

While national benchmarking reinforces a strong focus on quality across regions, researcher such as Rouse and O’Brien (2017), call out a disconnect in Australia between the intended notions of collaborative partnerships detailed in curriculum frameworks, and practices occurring in the field. Likewise in the United States, Gross et al. (2019) found that engagement practices were considered family responsibilities, even though the education policy documentation did not define it as such. There are international calls for improved execution of collaborative partnerships. American research by Cutshaw et al. (2022) and Vuorinen (2020) Swedish findings, concur with earlier Australian studies by Siraj et al. (2019) that a lack of consensus in collaborative partnership or engagement practice definitions leads to ambiguous interpretation and therefore ineffective application. Reflection on current interpretations and practices in the field, in addition to curriculum and framework reform, offers the potential to inform and guide an alignment of expectations and actions for families and educators in their roles in collaborative partnerships in ECEC services.

The Tensions in the Playground – the Emergence of a Metaphor

As authors we diverge slightly at this juncture to consider the theoretical underpinnings associated with the use of a metaphor as a means to potentially navigate through the diversity of literature that the narrative review unearthed. In this case, metaphor is understood to be a word, image or phrase used for rhetorical effect, offering comparison between things that are seemingly unrelated (Ortony et al., 1978). Collectively, the authors recognised metaphor as a valuable way to reorganise instilled patterns of thinking by offering clarity (Jakel, 2002), a way of enhancing communication, and opportunity for exploring of tensions emerging in the literature (Jubas & Seidel, 2016), as well as enabling sensitive subjects to be surfaced (Southall, 2013). Metaphor became the way for meanings to emerge as well as to see the meanings.

The use of metaphor helped Author One surface creative cognition, in terms metaphor inspiring creative thought and affording for revelatory insights (Southall, 2013). The understanding of metaphor is related to notions of cognitive development (Hoffman et al., 1991; Pollio & Pollio, 1979), and is noted for its usefulness in the learning process (Wilson, 2000). Way (1991) suggested that the use of metaphor allows for multiple interpretations involving assumptions and implications regarding the nature of language. The literature surfaced a variety of models for the use of metaphor with the authors electing to employ Cormac’s Cognitive Theory of Metaphor as this model supported the pursuit of an important cognitive phenomenon (Mac Cormac, 1985), that of the researcher in the meaning making of the literature review. Employing a cognitive theory of metaphor involved the authors interpreting metaphor as an evolutionary knowledge process in which metaphors mediate between people’s minds and culture (Mac Cormac, 1985), underpinned by a creativity hypothesis where the potential meaningfulness of metaphor does not surrender to basic paraphrasing (Jakel, 2002). The paper now moves through the literature related the consideration of stakeholders in collaborative partnerships, where the use of metaphor is woven throughout the discussion, to help in the sense-making process of comparing concepts surfaced in the literature to components of a tandem bicycle.

It Started on the Seesaw

The literature (Cottle & Alexander, 2014) highlights that the relationship of families and educators goes up and down, seeking a point of balance, like a seesaw. Families are recognised as a child’s first educator, bringing with them competencies that reciprocally support the educator in their role (Hadley & Rouse, 2018, 2019; Rouse & O’Brien, 2017). In reciprocal relationships the balance of power shifts gradually, like two children playing on a seesaw, as in Fig. 1. This up and down action of the seesaw reflects the engagement interrelationship between educator and families, making visible the intent of reciprocal, equal and trusting partnerships, where the shared goal on a seesaw is to maintain balance (not allowing the see-saw to touch the ground).

However, as each member of the partnership moves nearer or farther from the centre point, it requires a reciprocal movement from the counter members to maintain the balance. In relation to a collaborative partnership, this can be understood as the common goal, that can be preconceived, negotiated, and actioned in unison deliberately, or reactionary, or abruptly enforced by one party. This balance, the give and take interrelationship and reciprocity, surfaces in the literature and reflects current models of collaborative partnerships (Kambouri et al., 2021; Murphy et al., 2021). Unfortunately, current studies do not go far enough in addressing how to harness the shared synergy of stakeholders. With existing understandings of collaborative partnerships falling short in considering the continuation toward a common goal in situations where there is a shifting of power in a fluid and reflexive environment.

The Authors propose the metaphor of a tandem bicycle might better serve the needs of the educator and family in the playground, rather than the seesaw. Captured in the literature for its capability to enable the trajectory towards a common goal, is reflexivity. Reflexivity is a circular and bidirectional relationship, that impacts both parties (Laletas et al., 2017; Rouse & O’Brien, 2017). It could be argued that the qualities of reflexivity are better suited to the interplay between families, educators, and systems. As collaborative partnerships are often a vehicle for change, the differing assumptions and agendas of stakeholders is a consideration in its success. Research, such as Stone (2015), suggest a reconceptualising of participation models, to surpass hierarchical, patriarchal or coercive notions of power, rather than command and control models have emerged in modern times, supporting a conceptual shift in thinking around ways of working (Liu et al., 2017).

Assembling the Tandem Bicycle

The complexities outlined in the literature could be likened to assembling the bicycle, with a limited understanding of how design components fit together to achieve balance for forward motion. We argue that this is similar to the lack of clarity around mechanisms of family engagement (Sheridan et al., 2019; Vlasov & Hujala, 2017), and the limited articulation of role expectations in how collaboration and partnership are conceptualised (Hadley & Rouse, 2018), that is surfaced in the literature. This ambiguity has a flow on effect to poor quality partnerships in education settings (Rouse & O’Brien, 2017). Others, like Cottle and Alexander (2014), profess that the oversimplification of the complexities of the educator-family relationship has contributed to the difficulty in defining this term. Given this, we suggest then an instruction manual would be beneficial to support the assemblage of a bicycle that acknowledges the complexities of first building then riding the tandem bicycle. Like the building of a collaborative partnership, interpreting the instructions, coordinating the parts, and amalgamating these for successful construction requires an understanding of roles, and an appreciation for each other’s strengths.

As identified in the literature, practitioners are influenced by the curriculum and framework discourse under which they operate (Cottle & Alexander, 2014). This is supported by Hadley and Rouse (2018), who highlight the mismatch in the perceived role and expectations of self and other by educators and families. With varying conceptualisation of what family involvement and engagement looks like, it is of value to consider how the educator and family are positioned in the creation of collaborative partnerships. The literature surfaces the importance of decision making in a manner similar to where the seats are placed on the tandem bicycle.

There is consensus in the literature that family partnerships are a social construction, significantly influenced by factors at all layers of the ecological system, including policy priorities, culture, beliefs and attitudes (Cottle & Alexander, 2014; Fenech et al., 2019; Vlasov & Hujala, 2017). Cutshaw et al. (2022) and Wolf (2020) call for further research mechanisms for engaging with families. Wolf (2020) found that educators and families had differing expectations of roles. With curriculum frameworks often failing to provide clarity, the ambiguous interpretation and lack of tangible guide to enacting family collaboration weakens educator and family relationships (Gross et al., 2019), just like having the seats assembled to close, or too far away for rider use.

Educators and families are equally in need of an instruction manual for the tandem bicycle of collaborative partnerships in ECEC. Kambouri et al. (2021) reaffirm existing literatures’ depiction of components that support collaborative partnerships (for example, shared values and working as equals). It could be said that Kambouri et al. (2021), have seemingly identified the parts of the tandem bicycle, contributed to an instruction manual to build it, but unfortunately have fallen short in offering a guide for how to ride it.

Instructions for Riding a Tandem Bicycle

Riding a bike is complex, with a multitude of possibilities on exactly how to ride the tandem bicycle. One of the first decisions is where to sit on the bike and interpreting the instructions. Drawing on the literature, the authors offer refinements to existing conceptualisations of family-educator relationships and propose new ways of thinking about how to ride the collaborative partnerships bicycle. A series of steps are identified linking the tandem bicycle metaphor to the synthesised points that have emerging from the literature.

Step 1 – Negotiating Who Sits Where

Vying for seating position on the tandem bicycle surfaces in the literature where there is tension, and negation around stakeholder expertise and child knowledge; the family who know their child best and is paying for a service (Almendingen et al., 2021), versus the professional educator who studies child development (Owen et al., 2000). Fenech et al. (2019) call for professional advocacy to shift the image of family and educator in their partnership away from a consumer-service model to a child-centered, goal-oriented cohesive relationship. This perspective offers educators an opportunity to build families’ understandings of partnerships (Murphy et al., 2021), and evidence the value in educator-family partnerships.

Within the literature the construct of negotiation is linked to the notion of empowerment. For example, Laletas et al. (2017) acknowledge the capabilities of the families as knowledgeable, active, and equal participants in decision making. Further literature (Forry et al., 2011) draws into question whether families are provided an equal ‘seat’ in negotiations. Rouse (2012) suggests a model of partnership for engaging and collaborating with families in a manner where the focus is on shared empowerment resulting in positive outcomes for all stakeholders. Tightly coupled with the concept of partnerships are family centred practices which are seen as imperative in the ECEC (Dunst et al., 2019; O’Connor et al., 2018) as a way of empowering families. The literature review reveals that equal and balanced negotiation, like two equal sized seats on a tandem bicycle, are required for the notion of empowerment.

Step 2 – Steering and Setting the Direction for the Ride

Having successfully negotiated seating positions, the riders of the tandem bicycle (the family and educators) realise that irrespective of where they sit, they are empowered in decision making. Next is to steer the bicycle in a set direction. The literature suggests that setting a direction and steering to negotiate empowered relationships involves removing an economic/consumer-oriented view of a family’s utilisation of ECEC services, to a position of a truly shared direction (Fenech et al., 2019). The empirical research by Murphy et al. (2021) surveyed 318 educators and 265 parents across Australia and found conflicting opinions on the real or perceived impact of power relations between families and educators in this approach. Educators concerned that advocacy could be misconstrued as confronting or dictating top-down communication by the educator to the family, therefore impeding relationships (Fenech et al., 2019; Vlasov & Hujala, 2017). Fenech et al. (2019) considered the risk in educators acquiescing to family expectations to be equally as damaging as an authoritarian approach by an educator in decaying opportunities to build family understanding. What emerges from the literature is a gap, where Vuorinen (2020) suggests more research is needed, as currently the perception of power is dominant in family focused research findings of barriers to building effective partnership practices. The literature illuminates a problem, with these barriers being akin to a glitch in the fluidity of the bicycle’s steering. With an impediment to the ability to steer the direction will go awry.

Togher and Fenech (2020) observed that higher qualifications equated to greater educator capacity in initiating and facilitating quality improvements. This was supported by Fenech et al. (2019) finding higher qualified educators to be proactive in partnering with families, working with more focused intentionality towards families perceived needs. Vuorinen (2020) highlighted an asymmetric relationship that both educators and families grapple with in the ECEC context. Interestingly, Cutshaw et al. (2022) explored the mechanisms of family engagement in America, where a key finding was that irrespective of qualification level, a non-authoritarian educator was associated with higher partnership behaviours and family engagement, supporting an allegiance with earlier findings of the same by Owen et al. (2000).

Power in relationships can present differently. The intersection of this poignant research presented above suggests that higher qualified educators have a greater capacity to positively impact collaborative partnerships with families, only when the educator relinquishes their perception of self as expert authoritarian to create an open relationship on which to build elements of collaborative partnerships, such as trust, reciprocity, shared decision making. Moving towards relational and participatory behaviours underpin trusting and respectful relationships fundamental to empowerment (Laletas et al., 2017; Rouse, 2012). Perhaps the educator offering the family the front seat, and the ability to steer the tandem bicycle on their first journey would achieve this. Shifting perceptions of communication and engagement between families and educators towards a horizontal (rather than vertical) framing, goes someway to resolving barriers to empowered collaborative partnerships (Alasuutari, 2010).

In learning environments, engagement manifests itself in exercising agency. Much like two riders negotiating the direction on a tandem bicycle, reflexive deliberations prioritise the course of action amongst stakeholders (Kahn, 2014). Reflexivity allows for a person to understand their way of seeing the world, by considering how their own background and values shape their perspective (Skukauskaite et al., 2022). Armed then with this inward knowledge, a person can more effectively collaborate outwardly in a co-constructive relationship that embraces a variety of worldviews (Berger, 2015). Facilitating highly effective collaborative partnerships, stakeholders articulate and realise aims, where mutual objectives are counterbalanced, increasing the tolerance and capacity of stakeholders (Kahn, 2014). Mutual learnings evolve into joint truths and direction as Polk and Knutsson (2008) imply that the consensus towards these truths is gained through reflexive practices. Baumber et al. (2020) state “reflexivity plays a central role in transcending knowledge ‘silos’ to achieve new collective learning” (p. 396). Families and educators increase each other’s competencies and expertise as they alternate seating positions on the tandem bicycle. The process fosters the co-construction of new knowledge (Polk & Knutsson, 2008). It incites mutual learning that allows for the harnessing of power imbalances in a positive light (Vlasov & Hujala, 2017). This change in positioning allows for the continuation toward a common goal when there is an unequal weight contributed by one party, or the constant shifting of power in a fluid and reflexive environment.

Step 3 – Pedaling and Maintaining Momentum

To pedal a bike, a circular type of motion is used in a way where force is applied on the pedals throughout the pedal stroke. Like this motion, the literature surfaces reflexive practice, which occurs continually in the learning process. In this metaphor, the direction of travel reflecting the capacity to facilitate strength in the pedalling motion, creating momentum for the trajectory of the tandem bicycle, will also reflect the interchanging role of expert between family and educator.

In ECEC services, this type of practice would manifest a fluid and interchanging reliance on the strengths of both the educator and the family, each contributing to the shared objectives for the child. The literature reinforces the importance of the genuine acceptance of the shifting of knowledgeable expert between the educator and family create opportunities for shared support. For example, Vlasov and Hujala (2017) three country comparative study emphasised the need for a multi-perspective view of the child, rather than a shared vision, giving strength to the unique aspects [of child or situation] as seen by each stakeholder.

Highlighting family-centred and strengths-based practices, sees families as competent experts, where their position as their child’s first educator is celebrated. Sheridan et al. (2019) calls for future studies to consider both family and educator opportunities to voice beliefs and attitudes, rather than existing research that considers the perceptions of stakeholders by others. Being somewhat analogous, each of the riders of this tandem bicycle should be afforded the opportunity to share their experience of the journey for themselves, irrespective of their seating position or pedalling capacity at any given time. Kambouri et al. (2021) UK based findings championed this positioning through the development of their CAFÉ model. In the metaphor, riding is therefore an image of the fluid, responsive and everchanging constructs in the family-educator dyad of collaborative partnerships.

Given collaborative partnerships are valued for their attainment of problem-solving goals, is it possible for this tandem bicycle to be just the vehicle to create the successful momentum needed in ECEC for families and educators alike? This type of thinking offers continued momentum towards a shared goal, where the role of knowledgeable expert is fluid and constantly shifting, supporting both stakeholders. Reinforcing a strength-based initiative, grounded in an ecological framework, this shared support can be considered through illustration of the tandem bicycle metaphor in Fig. 2.

Riding in Tandem Shared Support

Working together (i.e., in tandem) enhances collaborative partnerships. The post-test results of a UK study by Kambouri et al. (2021) showcased stakeholders developing more empathetic and empowering approaches towards their counterparts as their valuing of collaborative partnership engagement increased. This was similar to an Australian study by Fenech et al. (2019) that evidenced the success of collaborative partnerships as the intentionality of educator and family’s engagement increased. There are two riders of this tandem bicycle: the family, and the educator. Each is unique, and brings with them a variety of strengths (Hadley & Rouse, 2018), knowledge of the child (Brown, 2019), and an underlying set of values and expectations (Phillipson, 2017). Impediments to successful partnerships were surfaced in an American study by Haines et al. (2022), where refugee families and educators had positive intentions to collaborate, but their assumptions of the other hindered outcomes. In an effort to decolonise power imbalanced ways of working towards successful collaborative partnerships, West et al. (2022) embraced an awareness of First Peoples’ cultural safety practices that lead to greater cultural humility and engagement of stakeholders. Encompassing these notions, Baumber et al. (2020) highlighted the transdisciplinary nature of collaborative partnerships, where a reflexive process of mutual learning facilitated enhanced and diverse worldviews. Therefore, irrespective of seating position, the trajectory is already established and communicated as a shared goal.

Referring to the metaphor of the tandem bicycle, the representation of reflexivity (as shown in Fig. 2) is in the chain, which moves fluidly and connects with the cogs (Berger, 2015; Skukauskaite et al., 2022). The pedals, which support the rider to push and propel in motion, are symbolic of shared support, and the unison of reflexivity together with support highlight the image of pedalling in tandem. Most crucial to this metaphor is the inference that it is possible to successfully ride the bicycle, in the agreed direction, without equal contribution of the members.

Where an imbalance of pedal force exists, such as the inability to pedal in a particular situation, the bike can absorb some loss of momentum, if balance is still in place. The unique design of a tandem bicycle allows for one or both of the parties to contribute to the momentum forward, regardless of their seating position. Tandem bicycles permit for two riders to pedal in unison, with equal effort, or for one party to ‘shadow’ pedal, undertaking the motion but contributing with less strength. Alternatively, one rider can pedal while the other freewheels. The visual image of the tandem bike embraces the fluid changes in motion and momentum that surface within the literature.

Akin to this would be when the family supports the educator in understanding contextual influences on a child, for example, providing an understanding of the diverse home life of a child. In this instance, the family pedals while the educator continues to participate in the pedalling motion, supporting the forward momentum, whilst providing for the capacity and agency of the family to flourish in this opportunity. Conversely, the educator may take sole control of pedalling in providing the child with explicit modelling of empathetic practices if this is not identified as a strength of the family, whilst valued as necessary in contributing to the shared support towards positive outcomes for the child. In this instance, the family may simply shadow the pedalling motion, or tuck their feet up and cheer on the educator, not having the ability to impact the momentum, but remaining on the bicycle and steering towards the agreed upon goal. As long as the bicycle keeps moving, form the fluid nature of those promoting its momentum, then the tandem shared support of educator and family towards positive outcomes for children are maintained.

Key Findings

Several key findings have emerged from a review of the literature and use of metaphor to support the process of meaning making.

-

1.

The use of a metaphor was effectual in conceptualising, interrogating, and presenting the literature review and aided in reorganising patterns of thinking. Using metaphor supported the researcher (i.e., Author One) in making sense of the complexities that arose from the literature regarding approaches to collaborative partnerships.

-

2.

Furthermore, it afforded an explanatory medium for colleagues (i.e., Authors Two and Three) so they could form a cognitive picture of linkages, connections and complexities within the literature presented. This in turn provided opportunities for deeper metacognitive processing of the content, whilst further enhancing the conceptualisation of the metaphor itself.

-

3.

The metaphor communicates the scholarly findings of the narrative literature review in a visual, tangible and identifiable way for a broader audience and readership. This includes challenging existing thinking akin to viewing educator-family partnerships as similar to the seesaw metaphor, to engaging with alternative and contemporary rhetoric that conceptualises successful collaborative partnerships as more like themes associated with the metaphor of the tandem bicycle.

-

4.

Finally, the paper offers a unique contribution to the conceptualisation and presentation of literature reviews using metaphor. Utilised here to facilitate sense-making of the tensions, dilemmas, and complexities that not only arising in the literature, but at the theory/practice nexus also. The transferability of using metaphor in this way supports scholars in navigating meaning making in literature reviews through a deep, reflexive, and unique approach.

Conclusion

This literature review sought to show the usefulness of metaphor as an evolutionary knowledge process to provide insight, and connections of concepts, politicising, and surfacing tensions arising within literature related to collaborative partnerships. The use of the tandem bicycle metaphor was a visual image that captured the ‘mediation’ between mind and culture, transforming knowledge and practices, which is vitally in a knowledge society. What emerges through the use of metaphor and narrative review presented here is a need to reflect the value of a shared understanding more deeply, as well as the roles and expectations for stakeholders in collaborative partnerships in early childhood settings.

The review also recognises that while there is significant research and literature that offers insights into understandings of collaborative partnerships broadly (Vuorinen, 2020) opportunities remain to further explore and investigate this phenomenon (Almendingen et al., 2021) including exemplary interactions that occur at the coalface (Murphy et al., 2021). What is evident is that the ECEC sector would benefit from a streamlining of the myriad of collaborative partnership models influencing their practices (Coelho et al., 2018). These types of insights would go some way in filling the gap in existing research and conceptualise a how to guide, giving voice to both the educator and the family on the tandem bicycle of collaborative partnerships (Petrovic et al., 2019).

References

Alasuutari, M. (2010). Striving at partnership: Parent–practitioner relationships in finnish early educators’ talk. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 18(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502931003784545.

Ali, T., Buergelt, P. T., Maypilama, E. L., Paton, D., Smith, J. A., & Jehan, N. (2022). Synergy of systems theory and symbolic interactionism: A passageway for non-indigenous researchers that facilitates better understanding indigenous worldviews and knowledges. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 25(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1876300.

Almendingen, A., Clayton, O., & Matthews, J. (2021). Partnering with parents in early childhood services: Raising and responding to concerns. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(4), 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01173-6.

Baumber, A., Kligyte, G., van der Bijl-Brouwer, M., & Pratt, S. (2020). Learning together: A transdisciplinary approach to student-staff partnerships in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(3), 395–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1684454.

Beaumont-Bates, J. R. (2017). E-Portfolios: Supporting collaborative partnerships in an early childhood centre in Aotearoa/New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 52(2), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-017-0092-1.

Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475.

Boyd, W., & Garvis, S. (Eds.). (2021). International perspectives on early childhood teacher education in the 21st century. Springer.

Brown, A. (2019). Respectful research with and about young families: Forging frontiers and methodological considerations. Palgrave Macmillan.

Choi, C. G., & Choi, S. O. (2012). Collaborative partnerships and crime in disorganized communities. Public Administration Review, 72(2), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02498.x.

Coelho, V., Barros, S., Burchinal, M. R., Cadima, J., Pessanha, M., Pinto, A. I., Peixoto, C., & Bryant, D. M. (2018). Predictors of parent-teacher communication during infant transition to childcare in Portugal. Early Child Development and Care, 189(13), 2126–2140. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1439940.

Cottle, M., & Alexander, E. (2014). Parent partnership and ‘quality’ early years services: Practitioners’ perspectives. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 22(5), 637–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293x.2013.788314.

Cutshaw, C. A., Mastergeorge, A. M., Barnett, M. A., & Paschall, K. W. (2022). Parent engagement in early care and education settings: Relationship with engagement practices and child, parent, and centre characteristics. Early Child Development and Care, 192(3), 442–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1764947.

Davies, R. (2008). The Jamaica early childhood curriculum for children birth to five. A conceptual framework. The Dudley Grant Memorial Trust. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/25868267/the-jamaica-early-childhood-curriculum-for-children-birth-to-five.

Dunst, C. J., Sherwindt, E., M., & Hamby, D. W. (2019). Does capacity-building professional development engender practitioners’ use of capacity-building family-centered practices? European Journal of Educational Research, 8(2), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.8.2.513.

Fenech, M., Salamon, A., & Stratigos, T. (2019). Building parents’ understandings of quality early childhood education and care and early learning and development: Changing constructions to change conversations. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 27(5), 706–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2019.1651972.

Forry, N. D., Moodie, S., Simkin, S., & Rothenberg, L. (2011). Family-provider relationships: A multidisciplinary review of high quality practices and associations with family, child, and provider outcomes. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/family_provider_multi.pdf.

Gross, D., Bettencourt, A. F., Taylor, K., Francis, L., Bower, K., & Singleton, D. L. (2019). What is parent engagement in early learning? Depends who you ask. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(3), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01680-6.

Hadley, F., & Rouse, E. (2018). The family–centre partnership disconnect: Creating reciprocity. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 19(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949118762148.

Hadley, F., & Rouse, E. (2019). Discourses/1, Australia: Whose rights? The child’s right to be heard in the context of the family and the early childhood service: An Australian early childhood perspective. In F. Farini & A. Scollan (Eds.), Children’s self determination in the context of early childhood education and services (pp. 137–149). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14556-9_10.

Haines, S. J., Reyes, C. C., Ghising, H., Alamatouri, A., Hurwitz, R., & Haji, M. (2022). Family-professional partnerships between resettled refugee families and their children’s teachers: Exploring multiple perspectives. Preventing School Failure, 66(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2021.1934375.

Hartman, S. L. (2018). Academic coach and classroom teacher: A look inside a rural school collaborative partnership. The Rural Educator, 38(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v38i1.232.

Hoffman, R., Waggoner, J., & Palermo, D. (1991). Metaphor and context in the language of emotion. In R. Hoffman, & D. Palermo (Eds.), Cognition and the symbolic processes: Applied and ecological perspectives (pp. 163–185). Psychology Press.

Hujala, E., Turja, L., Gaspar, M. F., Veisson, M., & Waniganayake, M. (2009). Perspectives of early childhood teachers on parent–teacher partnerships in five european countries. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 17(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930802689046.

ISSA (2016). Quality framework for early childhood practice in services for children under three years of age. International Step by Step Association (ISSA). https://www.issa.nl/quality_framework_birth_to_three.

Jakel, O. (2002). Hypotheses revisited: The cognitive theory of metaphor applied to religious texts. Metaphorik, 2(1), 20–24.

Jubas, K., & Seidel, J. (2016). Knitting as metaphor for work: An institutional autoethnography to surface tensions of visibility and invisibility in the neoliberal academy. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 45(1), 60–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241614550200.

Kahn, P. E. (2014). Theorising student engagement in higher education. British Educational Research Journal, 40(6), 1005–1018. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3121.

Kambouri, M., Wilson, T., Pieridou, M., Quinn, S. F., & Liu, J. (2021). Making partnerships work: Proposing a model to support parent-practitioner partnerships in the early years. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01181-6.

Laletas, S., Reupert, A., & Goodyear, M. (2017). What do we do? This is not our area. Child care providers’ experiences when working with families and preschool children living with parental mental illness. Children and Youth Services Review, 74, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.024.

Lang, S. N., Tolbert, A. R., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., & Bonomi, A. E. (2016). A cocaring framework for infants and toddlers: Applying a model of coparenting to parent–teacher relationships. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 34, 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.08.004.

Liu, Y., Sarala, R. M., Xing, Y., & Cooper, S. C. L. (2017). Human side of collaborative partnerships: A microfoundational perspective. Group & Organization Management, 42(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601117695138.

Mac Cormac, E. (1985). A cognitive theory of metaphor. MIT Press.

Markström, A. M., & Simonsson, M. (2017). Introduction to preschool: Strategies for managing the gap between home and preschool. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1337464.

Measuring and Monitoring Quality in Childcare for Babies and Toddlers. (2014). Kind en Gezin. https://www.kindengezin.be/nl/professionelen/sector/kinderopvang/kwaliteit-de-opvang/pedagogische-aanpak/het-pedagogisch-raamwerk.

Murphy, C., Matthews, J., Clayton, O., & Cann, W. (2021). Partnership with families in early childhood education: Exploratory study. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 46(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939120979067.

NCCA (2009). Aistear: The early childhood curriculum framework. National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. https://ncca.ie/en/resources/aistear-the-early-childhood-curriculum-framework/.

Nesbitt, K. T., & Farran, D. C. (2021). Effects of prekindergarten curricula: Tools of the mind as a case study. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 86(1), 7–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12425.

O’Connor, A., Nolan, A., Bergmeier, H., Williams-Smith, J., & Skouteris, H. (2018). Early childhood educators’ perceptions of parent–child relationships: A qualitative study. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 43(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.23965/ajec.43.1.01.

OECD. (2021). Starting strong VI: Supporting meaningful interactions in early childhood education and care. O. Publishing.

Ortony, A., Reynolds, R. E., & Arter, J. A. (1978). Metaphor: Theoretical and empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 85(5), 919–943. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.85.5.919.

Owen, M. T., Ware, A. M., & Barfoot, B. (2000). Caregiver-mother partnership behavior and the quality of caregiver-child and mother-child interactions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(3), 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(00)00073-9.

Petrovic, Z., Clayton, O., Matthews, J., Wade, C., Tan, L., Meyer, D., Gates, A., Almendingen, A., & Cann, W. (2019). Building the skills and confidence of early childhood educators to work with parents: Study protocol for the partnering with parents cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 197. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0846-1.

Phillipson, S. (2017). Partnering with families. In D. Pendergast & S. Garvis (Eds.), Health and wellbeing in childhood (2 ed., pp. 223–237). Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/9781316780107.016.

Polk, M., & Knutsson, P. (2008). Participation, value rationality and mutual learning in transdisciplinary knowledge production for sustainable development. Environmental Education Research: Sustainability in Higher Education Research, 14(6), 643–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802464841.

Pollio, M., & Pollio, H. (1979). A test of metaphoric comprehension and some preliminary developmental data. Journal of Child Language, 6, 111–120.

Provan, K. G., Veazie, M. A., Staten, L. K., & Teufel-Shone, N. I. (2005). The use of network analysis to strengthen community partnerships. Public Administration Review, 65(5), 603–613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00487.x.

Rouse, E. (2012). Family-centred practice: Empowerment, self-efficacy, and challenges for practitioners in early childhood education and care. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 13(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2012.13.1.17.

Rouse, E., & O’Brien, D. (2017). Mutuality and reciprocity in parent–teacher relationships: Understanding the nature of partnerships in early childhood education and care provision. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.23965/ajec.42.2.06.

Roussos, S. T., & Fawcett, S. B. (2000). A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annual Review of Public Health, 21(1), 369–402. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369.

Sheridan, S. M., Koziol, N., Witte, A. L., Iruka, I., & Knoche, L. L. (2019). Longitudinal and geographic trends in family engagement during the pre-kindergarten to kindergarten transition. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(3), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-01008-5.

Siraj, I., Howard, S. J., Kingston, D., Neilsen-Hewett, C., Melhuish, E. C., & de Rosnay, M. (2019). Comparing regulatory and non-regulatory indices of early childhood education and care (ECEC) quality in the australian early childhood sector. Australian Educational Researcher, 46(3), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00325-3.

Skukauskaite, A., Yilmazli Trout, I., & Robinson, K. A. (2022). Deepening reflexivity through art in learning qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 22(3), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120985676.

Southall, D. (2013). The patient’s use of metaphor within a palliative care setting: Theory, function and efficacy. A narrative literature review. Palliative Medicine, 27(4), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312451948.

Stone, M. T. (2015). Community-based ecotourism: A collaborative partnerships perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2–3), 166–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1023309.

Togher, M., & Fenech, M. (2020). Ongoing quality improvement in the context of the national quality framework: Exploring the perspectives of educators in ‘working towards’ services. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 45(3), 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939120936003.

Vlasov, J., & Hujala, E. (2017). Parent-teacher cooperation in early childhood education - directors’ views to changes in the USA, Russia, and Finland. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(5), 732–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1356536.

Vuorinen, T. (2020). It’s in my interest to collaborate … parents’ views of the process of interacting and building relationships with preschool practitioners in Sweden. Early Child Development and Care, 191(16), 2532–2544. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1722116.

Way, E. C. (1991). Views of metaphor. In E. C. Way (Ed.), Knowledge Representation and Metaphor (pp. 27–60). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-7941-4_2.

West, R., Saunders, V., West, L., Blackman, R., Del Fabbro, L., Neville, G., Rowe Minniss, F., Armao, J., van de Mortel, T., Kain, V. J., Corones-Watkins, K., Elder, E., Wardrop, R., Mansah, M., Hilton, C., Penny, J., Hall, K., Sheehy, K., & Rogers, G. D. (2022). Indigenous-led First Peoples health interprofessional and simulation-based learning innovations: Mixed methods study of nursing academics’ experience of working in partnership. Contemporary Nurse, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2022.2029518.

Wilson, S. L. A. (2000). Review of research: A metaphor is pinning air to the wall: A literature review of the child’s use of metaphor. Childhood Education, 77(2), 96–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2001.10521639.

Wolf, S. (2020). Me I don’t really discuss anything with them: Parent and teacher perceptions of early childhood education and parent-teacher relationships in Ghana. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101525.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kathryn Mason: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Project administration; Supervision; Visualization; Methodology; Analysis; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing; Visualization; Supervision; Project administration. Dr Alice Brown: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing; Visualization. Dr Susan Carter: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing; Visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

There was no funding associated with this research project. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of University of Southern Queensland. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (01/07/2021 and No. H21REA115). Informed voluntary consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mason, K., Brown, A. & Carter, S. Capturing the Complexities of Collaborative Partnerships in Early Childhood Through Metaphor. Early Childhood Educ J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01580-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01580-x