Abstract

Self-regulation is a critical emergent developmental competency that lays the foundation for children’s later psychosocial health and academic achievement. Recent work indicates that physical activity and energetic play opportunities support children’s self-regulation in the early childhood classroom. Many early childhood programs offer opportunities for children to engage in play, but teachers are rarely seen modeling physically active behaviors and face barriers to integrating opportunities for energetic play with early academic skills. Early childhood educational settings hoping to support children’s self-regulation development can provide multiple opportunities for children to observe teachers modeling physical activity, provide teacher support and scaffolding for physically active learning centers, and engage children in meaningful energetic play while promoting a range of academic skills. This article provides 10 research-based guidelines for supporting children’s self-regulation development through physical activity in early childhood classrooms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A growing body of evidence shows that physical activity—or energetic play—is associated with improved self-regulation in young children (Becker et al., 2014; Ludwig & Rauch, 2018; McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b, 2021a). Developing self-regulation skills during early childhood is essential because it supports a child’s capacity to regulate their systems of cognition, emotion, and behavior and is related to their academic success (Leerkes et al., 2008). Self-regulation is the integration of executive functions, including the ability to pay attention, switch focus, remember directions, and execute self-control in support of behavioral responses, such as waiting one’s turn to play at the water table or waiting to be called upon to answer a teacher’s question (McClelland & Cameron, 2012). Bolstering self-regulation, then, may be one way to keep children engaged and prevent them from missing out on learning opportunities in the classroom.

Physical activity has been associated with the primary components that make up self-regulation including working memory, attention, and inhibitory control (Pontifex et al., 2019) and self-regulation is one of the key areas of early childhood development across provincial (de la Famille, 2019), state (Housman, 2017), and Head Start early learning standards (Head Start Resource Center, 2010). Given this information, one could assume that physical activities and opportunities for energetic play would have a central role in preschool classrooms. However, recent work has shown that in about 50% of classrooms, children do not have sufficient opportunities to be physically active during the school day (Martyn, 2021). Typically, children spend 50–94% of their time in early education and care settings being sedentary (Alhassan et al., 2012; Pate et al., 2008; Statler et al., 2020).

For a number of reasons, it is rare for educators to successfully integrate physical activity with academic learning in their classrooms (Dinkel et al., 2017; Martyn, 2021; Tremblay et al., 2012). At the school level, teachers cite limitations to integrating physical activity in the classroom such as lack of space, accountability, and time for preparing and implementing physically active learning opportunities (Dinkel et al., 2017; Martyn, 2021; Tremblay et al., 2012). Another critical limitation is a school culture that places emphasis on core academic skills (e.g., literacy, numeracy) over healthy active living. At the student level, teachers share a concern that offering opportunities for physical activity in the classroom will increase disruptive behaviors and make it difficult to regain children’s focus after play (Martyn, 2021). Some teachers have also acknowledged a need to offer inclusive physical activity opportunities that accommodate child factors such as self-esteem, cultural beliefs, (dis)ability level, peer judgment, and gender diversity. For example, individual student characteristics may interfere with certain activities: students with cultural beliefs that restrict or oppose forms of movement like dance, Tai Chi, or yoga (Martyn, 2021) and physical spaces that were built for white, binary, able-bodied, and cisgender individuals (e.g., classrooms) may exclude many children from marginalized communities from participating in physical activities that require changing (e.g., swimming; Patel & Travers, 2021).

To enhance opportunities for physically active learning opportunities in early childhood classrooms, this article defines and identifies the relations between physical activity and self-regulation. We then provide information on interventions that have successfully incorporated physical activity in early childhood classrooms in ways that promote self-regulation. Based on this research, we offer guidance to teachers for implementing inclusive physical activity across their daily curriculum to support physical, socioemotional, and cognitive development.

Defining Physical Activity and Self-Regulation

Physical activity is defined as movement that results in energy expenditure (Caspersen et al., 1985). Adults’ physical activity is often planned and structured with the aim of improving fitness. In contrast, young children’s physical activity is characteristically short, driven by frequent changes in activity that are largely considered to be intrinsically motivated and freely chosen (McGowan et al., 2021a). Consequently, young children’s physically active behaviors are influenced by factors external to themselves (e.g., family conflict, parental emotions and stress, early childcare environment). Unfortunately, physical activity in educational contexts is often considered its own entity, falling under physical education curricula only. Although physical education is an important part of developing fundamental motor skills and supporting children’s healthy development (SHAPE America, 2013), preschool settings are more likely to emphasize or incorporate physical activity through energetic play (Isenberg & Quisenberry, 2002). Gender and (dis)ability play outsized roles in physical education, which can hinder participation of many children resulting in negative experiences that impact lifelong health and wellbeing of many gender-diverse children and children with (dis)ability (Ketcheson et al., 2021; Patel & Travers, 2021). Throughout this article, we use physical activity, energetic play, and movement interchangeably as most scientific evidence in children examines the influence of physical activity on self-regulation, yet we wish to be inclusive acknowledging a broader spectrum of physical activity in childhood that includes active living, play, and movement. This operationalization aligns with 24-h movement behavior policies—gaining momentum for young children (World Health Organization, 2019)—that use energetic play to characterize young children’s physically active behaviors. Energetic play also aligns more closely with common practices in early childhood that emphasize play as a basis for learning. Accordingly, this article focuses on how physical activity engaged in via opportunities for energetic play in the early childhood classroom supports children’s self-regulation and early academic skills.

Self-regulation is a broad construct that describes a child’s capacity to plan and adjust their behavior to an adaptive end, involving the coordination across several developmental systems: motor, physiological, social-emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and motivational systems (Davidson et al., 2006; Montroy et al., 2016; Zelazo et al., 2003). Neuropsychological traditions emphasize the cognitive components of self-regulation (i.e., executive functions), whereas, temperament traditions emphasize the construct of effortful control (i.e., modulating emotional reactivity to internal and external environments). In the context of the early childhood classroom, self-regulation relates to effective classroom functioning as children are required to coordinate multiple components of top-down executive control (e.g., attention, working memory, inhibitory control) in response to tasks (e.g., remembering multiple step directions amidst distractors).

A rapid period of development in self-regulation occurs during early childhood from ages 3 to 7 years old (Miyake et al., 2000; Montroy et al., 2016). Children improve their capacity to independently regulate and control their behavior without adult intervention (Zelazo & Frye, 1998). At the same time, the Cognitive Complexity and Control Theory (Zelazo & Frye, 1997) suggests that children develop the ability to hold more complex rules in mind, reflect on these rules, and organize these rules hierarchically as they get older (Zelazo et al., 2003). Across different perspectives of self-regulation development, children develop the different subcomponents of self-regulation at different rates. Emotional regulation precedes behavioral regulation, and the ability to delay a response (e.g., inhibitory control) precedes the other executive functions (Montroy et al., 2016). Although the preschool period is a sensitive developmental period for self-regulation, the brain mechanisms underlying these capacities continue to develop well into adolescence through early adulthood (Davidson et al., 2006). Importantly, experiences are thought to influence self-regulation across development, including the physical activity opportunities available in school. Physically active experiences are especially important for children from marginalized communities, as schools are the primary location where these children get their physical activity (Barnett et al., 2009). Leveraging physically active experiences by integrating them into classrooms, then, is a potent means by which we can address health inequities.

Physical Activity is Related to Self-Regulation

Research on the relations between physical activity and self-regulation in young children is limited relative to comparable research in older children and adults (Pontifex et al., 2019). However, research findings indicate that young children’s physically active behavior is related to improved self-regulation (Becker & Nader, 2021; Becker et al., 2014; Ludwig & Rauch, 2018; McGowan et al., 2021a). In particular, children meeting physical activity recommendations have less difficulty paying attention, controlling their impulses, and performing academically (Bezerra et al., 2020; Carson et al., 2019; Cliff et al., 2017; McGowan et al., 2021b). Moreover, young children meeting recommended levels of physical activity perform better on tests of emotional comprehension and exhibit fewer internalizing (e.g., anxiety and depression) and externalizing (e.g., aggression) behavioral problems (Carson et al., 2019; Cliff et al., 2017). Although there is no direct longitudinal evidence that physical activity predicts growth in self-regulation during early childhood, longitudinal evidence in older children suggests that greater time spent sedentary is associated with reduced psychological well-being in adolescence (Straatmann et al., 2016). This evidence collectively suggests that physical activity may support the development of self-regulation during early childhood.

In practice, children engage in physical activity in brief bursts of energetic play. There is strong empirical evidence demonstrating that a brief burst of physical activity lasting 16–25 min at moderate intensity (e.g., breathing harder as if you are moving somewhere because you are late) improves components of self-regulation, including attention and inhibitory control across all ages (Pontifex et al., 2019). Providing greater opportunities to engage in movement throughout the school day—even in short bursts—enhances academic achievement, improves on-task behavior, and increases attention (Hillman et al., 2019; Howie et al., 2014, 2015; Mahar, 2011; Norris et al., 2020; Pontifex et al., 2013; Szabo-Reed et al., 2017, 2019; Watson et al., 2017). For young children, movement can help them regulate their emotions and behavioral self-control (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b; Yang et al., 2020). This means that energetic play and movement may help young children manage tantrums and outbursts. In sum, there is strong empirical evidence that physical activity enhances children’s self-regulation. Therefore, energetic play and movement should be critical components of young children’s learning environments.

Empirical Evidence for Integrating Physical Activity in the Classroom

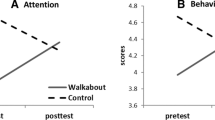

Research has shown that physical activity can be integrated into the early childhood classroom by using both teacher-led and child-directed learning centers (Mavilidi et al., 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018; McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b). Infusing physical activity into classroom lessons engages children and reduces off-task behavior (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b). Our recent research showed that engaging young children in physically active math lessons resulted in a 60% reduction in challenging behaviors compared to seated math lessons (McGowan et al., 2021b), demonstrating that physical activity infused into the classroom can boost young children’s self-regulatory skills. This means that after the physical activity, children are more likely to focus their attention on their target task and less likely to engage in disruptive behavior. Thus, children who are physically active can better regulate their behavior and are less reactive to internal and external distractions.

A recent study of 3–5 year old children integrating physical activity while teaching young children concepts such as counting, ordinality, and cardinality resulted in equal learning and retention compared to activities aimed at teaching these concepts using traditional seated math games (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b). In these studies, children participated in seated and energetic play math games on two separate days. On the seated day, children played three math games: (1) counting a plastic figurine along a number line corresponding to a quantity depicted on a card, (2) determining whether a quantity of animals depicted on a card was less than or greater than five by moving their piece on a number line, and (3) counting the number of bears corresponding to a quantity depicted on a card into their cup. On the energetic play day, children played the same three games with movement: (1) counting a quantity on a card and moving like an animal to the corresponding position on a number line, (2) determining whether a quantity of animals depicted on a card was less than or greater than five by throwing a bean bag into a hula hoop, and (3) bouncing a ball in a hula hoop corresponding to a quantity depicted on a card. Following the energetic play games, children exhibited better behavioral self-regulation than following the seated games with no weakening of numeracy learning. These studies demonstrate that integrating energetic play with core academic content is a powerful approach to reduce the time children spend sitting in the classroom, which can lead to meaningful changes in physical activity, learning, and self-regulation (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b).

What We Know About Dosage and Intensity of Physical Activity

A first step to integrating physical activity into the classroom is to know how much physical activity children need and at what intensity of effort. Recent World Health Organization (2019) guidelines released for young children suggest that children under age 5 should get 10–13 h of good sleep, 3 h of physical activity at a variety of intensities, and spend no more than 1 h on sedentary screen time during a 24-h period. These recommendations are consistent with the most recent edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee, 2018), which states that 3–5 year old children should engage in a mix of active play and a variety of structured physical activities, with a reasonable target time of 3 h per day across all intensity levels. In alignment with World Health Organization guidelines, Fig. 1 provides a printable poster for classrooms to use as a visual reminder to offer movement throughout the day.

Intervention research integrating physical activity with academic skills in classrooms indicates that children yield the highest gains in self-regulation and well-being following activities in which they are engaged in energetic play for at least 9–13 min of a 20 min lesson (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b). In contrast, classroom lessons in which children were only active for 2–5 min demonstrated no improvement in self-regulation, although children indicated they enjoyed the lesson more than being seated (Howie et al., 2014, 2015; Mavilidi et al., 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018). Interesting to note is evidence from small samples of kindergarten students with Autism Spectrum Disorder showing that brief (~ 5 min) bouts of physical activity embedded within the typical school day improve student engagement and on-task behavior in lessons immediately following such activity breaks (Harbin et al., 2022; Miramontez & Schwartz, 2016). While we recognize shorter bursts of activity may be beneficial for some children, in general, planning active learning opportunities for at least 20 min will ensure children accrue the minimum 10 min being physically active that yields the greatest physical and cognitive benefits.

In addition to duration, physical activity guidelines suggest children accrue a variety of intensities in their movements throughout the day (World Health Organization, 2019). Greater amounts of energetic play are best for promoting children’s health and development (World Health Organization, 2019). Higher intensity activities like running, using a wheelchair, and jumping jacks protect heart health and reduce feelings of anxiety and depression (Helgerud et al., 2007; Rebar et al., 2015). Walking or stretching while standing or seated, however, are good for restoring attention (Bailey et al., 2018). The continuum of intensity ranges from standing to light walking to higher intensities in the “huff and puff” category that result in a higher heart rate or get children out of breath. Finding ways to make learning active across a variety of intensities throughout the day will offer the most benefits to children (World Health Organization, 2019), particularly when higher intensity activities from the “huff and puff” category are included (Brown et al., 2006). A critical limitation to current research is that many studies do not consider inclusive and adaptive movement programs that can be performed by students regardless of (dis)ability. To address this limitation, we offer teachers a variety of activities that may be adapted to different mobility needs and acknowledge that inclusive physical activity is best when personalized and student-centred (Hauck et al., 2021).

-

Light Intensity Activities: stretching; throwing a ball; sliding down a slide; slow and easy crawling; marching from place to place; reaching for the sky and reaching to touch the ground. These activities may be performed while sitting or standing.

-

Moderate Intensity Activities: fast walking; using a wheelchair; repeated jumping, hopping, or skipping; climbing up an incline; climbing on play equipment; swinging with legs kicking.

-

Vigorous “Huff and Puff” Intensity Activities: jogging; running; walking up three or more stairs; bicycle/tricycle riding; three or more repetitions of jumping jacks or jumping rope; climbing across bars; wheelchair sprinting.

Importantly, it is essential to promote movement in positive and encouraging ways. Movement should never be used as punishment (e.g., doing jumping jacks for not waiting their turn) or taken away (e.g., loss of outdoor time due to hitting) for challenging behavior. Responsive educators may identify challenging behaviors as a reaction to a child’s need for more movement opportunities in the daily schedule and may instead use movement to help children to regulate their behavior and emotions in a healthful way. Consider the following example:

When Jayla, a pre-kindergarten student, became frustrated with the counting lesson, they threw the counting bears all over the floor. Their teacher, Mx. Tremblay, expertly and immediately engaged movement to address the strong emotion. First, Mx. Tremblay calmly reminded Jayla of the dangers and damage that could result from throwing toys. Then, recognizing Jayla’s frustration may reflect a need for an active break, suggested Jayla move in a bear crawl to pick up each bear, count each one as they pick them up, and return each bear safely to the bucket.

Teachers Matter for Children’s Movement

Teachers play an instrumental role in helping children to stay active because schools are where the majority of children, especially those children from marginalized communities, get their physical activity (Barnett et al., 2009). Unfortunately, children are least active during classroom lessons (Bailey et al., 2012) and children enrolled in center-based preschools and full-day kindergarten are less active than their part-time or home-based childcare counterparts (Tucker et al., 2015). Given that typical educational programming is predominantly sedentary, this article provides guidance to support teachers in offering children more opportunities for energetic play and movement of varying intensities to support self-regulation, wellbeing, and ultimately, academic achievement.

Ten Research-Based Guidelines for Creating Opportunities for Physical Activity and Self-Regulation

With a bit of ingenuity, energetically playful and physically active lessons can be integrated throughout the school day—it’s as simple as adding movement to existing, but typically seated, learning opportunities. And fortunately, research shows that these energetically playful lessons do not minimize children’s learning (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b). The following sections identify 10 research-based guidelines for infusing physical activities into the early childhood classroom to support young children’s self-regulation, physical development, and early academic skills. Of note, these guidelines have been compiled using a combination of the most-updated recommendations for young children’s physical activity engagement (2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee, 2018; World Health Organization, 2019) and a synthesis of original research studies examining physical activity integration in the early childhood classroom. We also offer practical guidance for designing meaningful active learning opportunities to support these skills. We describe classroom practices using examples (all names are pseudonyms) to guide readers in how to implement these guidelines into early childhood classrooms. Although we focus on early childhood classrooms, we look forward to future work that will consider how these recommendations can be applied across the lifespan and in other daily settings, such as work. We follow gender inclusive writing guidelines (Government of Canada, 2022), making use of diverse titles (e.g., Mx., M., Mt., M*., teacher) and pronouns (e.g., iel, they, he, she, ey, xe, zi) that represent gender diversity. We refer readers to the Non-binary Wiki (http://nonbinary.wiki/wiki/Gender_neutral_titles) and Égale Canaada’s pronoun usage guide (http://egale.ca/awareness/pronoun-usage-guide/) and Pronuns.org (http://pronouns.org/) as additional resources for understanding the use of gender inclusive language. Table 1 includes a list of the guidelines for best practices in supporting physically active learning. Each of these strategies represents developmentally appropriate practice and can be successfully incorporated into early childhood classrooms, including those serving students from marginalized communities.

Incorporate Physical Literacy Principles into the Curriculum

Physical literacy is recognized as developing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to live a healthy, active life (Mandigo et al., 2009; Whitehead, 2001). Physical literacy includes learning about our bodies and how they move including the language to describe our bodies and movement. For example, engaging in movement songs like Happy and You Know It or Head Shoulders Knees and Toes supports children to develop language for describing bodies. Mindfulness practices, such as Yoga Nidra and body scan meditation can also be used to cultivate embodied awareness. Educators can begin with more familiar parts like arm, leg, hand, foot, and advance the game to include elbow, knee, hip, wrist, and ankle to enhance language skills and physical literacy. Culturally-responsive teachers introduce and encourage children to use these terms during songs and play in official languages, such as English and French in Canada, as well as in the home languages represented in their classroom or community.

Teachers promote physical literacy by introducing and defining fundamental movement skills that will support children in engaging in lifelong physical activity (Barnett et al., 2016). The building blocks of more complex movements required to participate in sports, games, and other physical activities include fundamental movement skills in the domains of object control (e.g., kicking, catching, throwing, bouncing), locomotion (e.g., running, jogging, leaping, jumping, hopping, skipping), and body management (e.g., balancing, rolling, climbing; Robinson et al., 2015). For example, during a transition in which children count backwards as they are dismissed from circle time, a teacher could employ an activity in which each child may choose how they will move to line up and perform that movement. Children select from tiptoeing, galloping, crawling, hopping, skipping, rolling, and more. Teachers should make an effort to expand beyond western-normative activities to incorporate traditional games and activities of Indigenous, Black, Brown, Hispanic, Asian, and non-western cultures by consulting and involving local Indigenous and racialized communities and organizations in designing programming (Patel & Travers, 2021). When children are presented with opportunities to co-create physical activity regularly, they can try out and practice a variety of movement skills while also learning the vocabulary to describe these movements. These approaches allow teachers to actively create more welcoming and engaging environments for all students.

Perhaps most importantly, children should learn that the best activities are those they enjoy doing and will enjoy doing for life (Dishman et al., 1985). Thus, it is important that children sample a variety of activities to identify what types of activities they find the most enjoyable. Creating opportunities for children to experience a range of movements including dance to varied music genres, yoga, Tai Chi, stretching, games, and sports introduces a variety of fun movement possibilities for children. In this way, children can develop patterns of physical activity that will bring them joy across their life.

Even young children can learn about the importance of engaging in physical activities across the varied intensities including light, moderate, and vigorous “huff and puff” categories which are most beneficial for physical health (Brown et al., 2006; World Health Organization, 2019). It is important, however, to help children understand the “huff and puff” category in a concrete way and to offer experiences that help them to reach this level. For example, teachers might introduce heartbeats by first reading about them (e.g., The Children’s Human Body Encyclopedia by Steve Parker) and then helping children to feel their heartbeat and talk about how this beat is the movement of blood in their bodies. That is, when they move fast, their blood moves fast, and the heartbeat is faster or stronger. Teachers can bring this learning to life, by having children feel their heartbeat after resting and then have children run in place and feel their heartbeat again drawing attention to the faster beat or pounding in their chests. Then teachers can provide children rotating experiences that encourage children to move in the “huff and puff” range and then in a light range to feel their contrasting heartbeat during each experience. Teachers can incorporate meditation and mindfulness practice to allow children to feel how their heartbeat changes with relaxation activities and help them make note of how it feels in their body and what emotions they feel after different intensities of movement.

To offer opportunities for children to engage in the “huff and puff” category, Table 2 outlines sample lessons created to support children to play in the “huff and puff” range and develop numeracy skills ((McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b). As measured using pedometers, children participating in these activities took 1000 more steps in the “huff and puff” category of energetic play—important for protecting against cardiovascular and metabolic diseases—than when they participated in the seated versions of the activities (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b). To play these active learning games, children rotate through a variety of 5-min play stations including games such as Farmers (play for 5 min), Juice makers (play for 5 min), and Beanbag toss (play for 5 min; see Table 2). Throughout the whole active experience, children spend 15 min physically active at or above light intensity. Encouraging children to feel their heartbeat during various experiences helps them to feel light compared to vigorous intensity and develop a concrete way to understand their bodies. Teachers can help children also learn to name emotions they feel as they engage in activities, which is an important component of self-regulation development during early childhood.

Build Opportunities for Movement into the Daily Schedule

A great place to start is to create opportunities for children to move more and sit less during daily activities and routines. For example, teachers can invite or dismiss children from group time by prompting them to crawl like a bear, hop like a frog, or roll like a log. Including dancing and songs with finger plays or motions during group times can promote children’s movement and physical literacy by labeling body parts and/or movements (e.g., gallop, twirl, tiptoe) giving children new ways to move and language to describe their movements. During shared reading, teachers can promote physical literacy by reading texts that define and encourage movement (e.g., Barnyard Dance by Sandra Boynton, Move! by Robin Page and Steve Jenkins, Get up and Go! by Nancy Carlson, or Shake a Leg! By Constance Allen and Maggie Swanson) or by encouraging children to act out new vocabulary or story plots. Teachers can incorporate meaningful energetic play opportunities into play centers and instructional activities they already plan. For example, if a typical learning center involves the child counting and tallying various types of fruit while seated, the teacher can modify this play center to incorporate movement by engaging the children in a fruit basket toss and tallying the number tossed in or out of the fruit basket. Teachers can move this game into the “huff and puff” category by placing the fruit in baskets on one side of the room and a fruit stand on the other side. Teachers and children can “order” various quantities or patterns of fruit while other children must “deliver” the fruit by selecting the ordered fruits from the baskets and skip, gallop, or roll them to the other side of the room to deliver to customers at the fruit stand.

Organizing the classroom schedule with a balance of sedentary and varied intensities of activity across the school day can facilitate young children’s learning. Because short bouts (~ 10 min) of vigorous “huff and puff” intensity activities can support children’s attention and self-regulation (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b; McGowan et al., 2022), teachers may consider planning vigorous movement opportunities to precede times of more sedentary lessons. For example, teachers might engage children in a vigorous music and dancing experience prior to sitting for their morning meeting, play a game in which children move when they hear rhyming words to a poem before sitting for book reading, and engage in small group instruction after children have returned from outdoor play.

Integrating brief periods of energetic play repeatedly across the school day, every day, promotes physical development and academic learning. For example, active mathematics lessons delivered daily across one month resulted in higher counting and number identification skills (Mavilidi et al., 2018). Similar benefits have been identified for active learning opportunities for language (Mavilidi et al., 2015), science (Mavilidi et al., 2017), and geography (Mavilidi et al., 2016).

Encourage All Forms of Movement

Young children vary considerably in their skills for a variety of fundamental motor skills like running, hopping, skipping, and throwing (Palmer et al., 2019). Some children may be able to catch a ball while others may be more comfortable bouncing and tossing, still others may roll the ball along the ground and (dis)ability visible or invisible will play key roles in children’s movement patterns. Even a child who can perform more advanced motor skills (e.g., galloping) may lack skill or experience with other foundational skills (e.g., tossing) reflecting the wide range of trajectories that are present in children’s motor development (Hulteen et al., 2018). Successful teachers provide diverse and multiple opportunities and encourage a range of motor skills including hops, skips, gallops, twirls, jumps, toss, tiptoeing, and more. These fundamental motor skills form the foundation for later complex movements. However, these fundamental motor skills exclude children with (dis)abilities, so teachers should be mindful to adapt activities to be inclusive for all mobility patterns.

In early learning opportunities, it is more important for young children to engage in movement and develop fundamental motor skills than it is to focus on the exact movements (Apache, 2005). As such, inclusive teachers create movement opportunities for children to use their varied and developing skills. That is, teachers create “win–win” movement opportunities, so all children have continued experience with movement rather than being “out” when they make a movement mistake. For example, when playing a Follow the Leader or Simon Says style game, children who move when the leader didn’t say to move might move from one side of the room to another but will continue to engage in the game. For musical chairs, rather than removing the child who doesn’t find a seat, teachers may engage the children in a discussion of fractions/parts to identify how to share the remaining chairs. In this game format, all children continue to engage in the movement to further develop their skills throughout the game.

Model Physical Activity Inside and Outside the Classroom

Adults in young children’s lives, including teachers, are important role models for young children to develop early patterns of physical activity that will continue across their lifetime (Faith et al., 2012). Effective teachers play along with children so they can model how to execute a range of motor skills (e.g., show how to gallop or skip) as children develop (Barnett et al., 2016; Logan et al., 2012).When teachers perform motor skills and are physically active alongside children in classroom activities, children experience greater levels of physical activity and are more motivated to be active themselves (Cheung, 2020). Outside the classroom, teachers who are physically active tend to incorporate a more positive model of healthy lifestyle behaviors for children to learn (Cardinal, 2001; Smuka, 2012). Although there is less research on the role of early childhood educators’ modeling of physical activity for young children, one study from Hong Kong showed that preschoolers engaged in higher physical activity levels when they were taught by a teacher who played along and thus, the teacher was more physically active themselves during active lessons (Cheung, 2020).

Young children with active caregivers—parents and teachers alike—are also likely to continue to be active throughout development (Yang et al., 2020). Early childhood educators can model physically active behaviors and encourage children’s physical activity by participating in the activities themselves. This co-participation may be particularly important for young children socialized as girls and young children who are less active at home (Edwardson & Gorely, 2010).

Example

When Mt. TJ, a kindergarten teacher, noticed a child drawing chalk lines on the concrete outside during recess, he/they asked about the marks. “I want to see how far I can jump,” the child responded. Leveraging the child’s interest, Mt. TJ joined the play and jumped from the chalk starting line. As other children joined the game, together they used chalk to measure and record each other’s jumps on another section of the concrete.

In addition to physically engaging with children, teachers model their active lifestyle with children by sharing with children about the healthy active living opportunities they enjoy.

Example

During their morning meeting, Teacher Garcia talked with xe students about riding xe bicycle to school, which sparked a conversation about active transportation. This then led to an activity in which the class graphed how each child and teacher had traveled to school that day.

Further, teachers can discuss with children how they find ways to be active at school like taking the stairs, going on a nature hike, or playing on the playground during outdoor time.

Make Movement Meaningful and Fun

It is important that educators integrate physical activity into learning opportunities in meaningful ways. Implementing short physical activity breaks (i.e., shorter than 10 min) as placeholder or transition activities within instructional contexts offers little to no benefits to children’s physical and cognitive development, but is proven to increase enjoyment of learning. For instance, having children march while spelling words was not associated with improvements in academic learning or self-regulation relative to seated lessons (Howie et al., 2014). Instead, infusing physical activity into meaningful learning opportunities helps children regulate their emotions and behavior immediately after the lesson and supports improved retention of literacy, foreign languages, geography, science, and math concepts up to one month later (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021a; Mavilidi et al., 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018).

Like all early learning experiences, movement opportunities should align with children’s interests and have a purpose (Guirguis, 2018). Surprisingly, some young children have already learned to dislike physical activity (Barnett et al., 2019), which is especially true for gender diverse children and those children with intersectional identities. For example, a racialized, queer, non-binary child with immigrant status has a different experience than a white, queer, non-binary child with birth-right citizenship. Preparing meaningful and fun movement experiences can engage all children in the action. Creating a context for movement such as a story, problem, game, or challenge helps promote engagement. Table 2 offers examples of meaningful active learning experiences like saving the animals who have escaped their farm enclosures.

Example

In an outdoor lesson on time and equalities, Teacher Zeynad and iel/they/her class used stop watches to record racing times for all children and teachers and graphed them. Based on the books and iel/they/she have been reading and discussions iel/they/she are having about growing healthy bodies, Teacher Zeynad encourages children to brainstorm and test many ways to run faster each time they race. The children test drinking water, changing their shoes, eating spinach they collected and washed from the class garden, stretching before their next race and more. Testing their ideas created purpose and encouraged a positive experience for children engaging in physically active lessons.

Children need to know that developing a healthy body is important and that just like eating healthy foods, drinking water, and sleeping, being active helps them to have a healthy body and mind. Teachers help show children that physical activity provides many opportunities for fun and enjoyment throughout their lives (Hooker & Masters, 2016, 2018; Yemiscigil & Vlaev, 2021). Through discussions and enjoyable participation in physical activity, teachers help children to see movement as a fun way to play, be adventurous, and interact with friends and family. Just like in other areas of learning, teachers can help children to identify individual and achievable goals to develop a new movement skill or to improve a current skill. Teachers and children can track their accomplishments on charts or graphs to visually display their growth. Setting goals and reflecting on advancement in skills supports children’s initiative, motivation, and growth mindset. Moreover, it helps children to see the benefit of goal setting. It is important for teachers to remember to provide multiple opportunities for children to engage these skills so they can see their growth across time. When physical activity is connected to learning, about connecting with people we love, and is fun, it supports healthy active living across the lifespan (McGowan et al., 2022).

Incorporate Movement in Children’s Playful Learning Centers

When children are provided with meaningful opportunities for movement in the context of their play and learning, they will be active. Encouraging children to self-select where they play during learning centers or free play time is the first step to offering active movement for children. Teachers can promote a range of movements as children independently transition from one learning center to another by including a foam hopscotch or taped numbers and movement signs (e.g., hop like a bunny, leap like a kangaroo, slither like a snake, roll like a log, float like a dandelion seed) on the floor to guide children. Offering flexibility in how children engage at centers can also promote children to use movement to expend energy in ways that help them to engage fully in the learning. For example, allowing children to stand or sit at the puzzle table and including floor puzzles in this learning center permits children to choose various ways to move their bodies while they work on their puzzles and is inclusive teaching. Providing ample space for children’s constructions in the block area encourages children to be more active as they carry and move blocks from the shelves to their building space. This approach permits the construction of larger and more complex structures that may require children to stand, scoot, crawl, and stretch as they build while being inclusive to the need for space for walkers, wheelchairs, and other mobility assistance equipment integrating objects that move like balls, carts, and cars may spark children’s interest in building ramps and engaging in rolling experiments that encourage physically moving their bodies as they roll and test out the properties of the objects, experimenting with angles and testing out concepts like inertia and speed.

Transforming typically seated activities into active learning opportunities can be a fun and engaging way to promote physical activity and learning. The following examples offer ways to incorporate movement into typically seated activities.

Example

In children’s exploration of carnivorous and herbivorous dinosaurs, Teacher A. created an active lesson by labeling two bins with cardboard cutouts of two dinosaurs with open mouths and encouraging children to toss plastic foods to “feed” either a carnivorous Raptor or herbivorous Apatosaurus.

This same transformation can be applied for any sorting, grouping, or sequencing task.

Example

M. Bahar created movement opportunities within the dramatic play area of iel/their classroom while the children studied bugs. Iel/they provided insect costumes and encouraged children to move around the area like the bugs they portrayed by walking like an ant, hopping like a grasshopper, crawling like a caterpillar, and “flying” like a bee.

Example

Mt. Lee created a speed test in the block area by helping the children to create various sized ramps and barriers for their cars. Children took many quick steps as they tested and collected their cars from across the classroom.

Example

M*. Garcia created an addition/subtraction game in which ey constructed a large number line (1–3 metres or 5–6 feet wide) out of tape on the floor. Children solved equations by moving across the number line.

Each of these opportunities promotes energetic play, development of fundamental motor skills, and important cognitive skills and/or content knowledge. We acknowledge that different forms of movement should be encouraged and allowing students to select how they move will make these activities inclusive to all students.

Take the Activity Outdoors

Outdoor time provides diverse opportunities for children to be active and develop a range of fundamental movement skills. The environment (e.g., open spaces, uneven surfaces), structures (e.g., climbing structures, swings), and equipment (e.g., tricycles, digging tools, balls) provided in the outdoor play space naturally encourage children to move in various ways. Teachers enhance learning when they join children’s play by modeling movement skills and enjoyment of being active, motivating children’s engagement, and expanding learning with challenges (e.g., “I wonder if you can move all the way to the far tree.” “I wonder what the fastest way is to move these balls across the grass.”). As teachers play, they can observe and recognize development in children’s movement skills.

Example

Mer Conrad verbally recognizes Marcus’ growth by saying, “Marcus, you climbed all the way to the top of the structure today. You must be working hard on your climbing because last week you climbed halfway up. Congratulations on your hard work!”

Example

Dr. M. takes the opportunity while the class is playing outdoors to have children draw what they see. This activity is done throughout the school year and children and Dr. M. talk about how with seasons, our environment changes. Dr. M. talks to children about how by observing these changes in our environment, we can cultivate closer connections to our natural environment and this is an important piece of protecting it. When children observe that certain trees are cut down to make way for new buildings or built environments, Dr. M. talks to children about how humans impact the environment and this is like when we litter and don’t take care of it. Dr. M. may also engage the class in environmental monitoring activities and park cleanups to cultivate a relationship to our natural environments in children.

Children are generally more active outdoors compared to indoors (Coe, 2020), so savvy teachers may choose to take learning opportunities outdoors. Providing opportunities to get outside and restructuring learning activities to access the outdoor environment may increase the amount of daily physical activity children accumulate. For example, teachers and children can take their science journals and binoculars outdoors to engage in a nature hike before they write and draw their observations in their journals.

Example

During a science lesson on speed and surfaces, Mx. H. and the children moved outdoors to test hypotheses about how fast balls would move over the various surfaces in the play yard (e.g., grass, concrete, gravel, mulch).

Example

During a lesson on measurement, M*. Jackson and the children collaborated to create a map of the outdoor play space. In small groups and brandishing measurement tools including measuring tapes, yarn, their own bodies, clipboards, graph paper and markers, groups measured the length of the bike path, the height of the climbing structure, the distance across the open field, and the circumferences of their favorite trees as they charted their playground onto their map.

Balance Opportunities for Unstructured and Structured Play

It is important that children have opportunities for unstructured, independently-motivated activities as well as structured, teacher-led activities (Clevenger et al., 2021). Unstructured play might include free play outdoors in which children self-select from various play structures, swings, climbers, tricycles/scoot cars etc. Indoors, children can select from a variety of play centers where teachers have integrated movement opportunities into the center (see 6. Incorporate Movement in Children’s Playful Learning Centers). Unstructured, child-led opportunities to pursue individual plans and goals encourages children’s autonomy, independence, risk-taking, problem-solving, and discovery. Child-led activities are also inclusive to gender-diverse and (dis)abled children (Hauck et al., 2021; Patel & Travers, 2021). As teachers play alongside children in these self-selected experiences, it is a great time for teachers to identify children’s interests, strengths, and goals. These observations should inform teachers’ planning for structured movement opportunities.

Structured, teacher-led movement experiences should build on children’s interests and skills. For example, during a class meeting time, a teacher might introduce new movements or an active game to children that provides new vocabulary, instructions, or a discussion of how or why to use the new movements. These new movements should be relevant to children’s ongoing explorations.

Example

M*. Taylor’s class is studying how their bodies move. He/they noticed that most children identify their leg, foot, and toes, but are not using the terms knee, ankle, and hip yet. He/they introduces these new terms and engages children in a dance, highlighting these new body parts as well as familiar ones. In addition, he/they has planned center activities to reinforce this new information. Children are labeling bodies they painted in the science area and there are opportunities to dance to music in the dramatic play theatre where he/they will encourage children to discuss how they are moving their bodies using the new vocabulary (e.g., “J. and D. are wiggling their hips side to side.” “Others are bending their knees as they dance.”). Later when M* Taylor and the children go outdoors, he/they has planned a collaborative game in which children choose different body parts (e.g., wrists, elbow, hip, ankles) and problem-solve how to move from one point to another.

A successful balance of structured and unstructured opportunities introduces new ideas and content and is followed up by opportunities to use these new skills independently and in unstructured ways.

Promote Movement That is Culturally-Responsive and Inclusive

Creating culturally-responsive and inclusive movement opportunities ensures all children can participate, enjoy, and develop skills within the activity regardless of their experiences or abilities (Palmer et al., 2017). Offering children choice in how they are active during a lesson offers autonomy and positions children as experts as they share with their teachers and peers the movements they enjoy (Palmer et al., 2017). For example, teachers can create games with children in which each individual child selects how they and their peers move during various genres of songs, which allows children to highlight their strengths and encourages peers to try out new and diverse movements.

It is important to plan experiences that align with children’s interests and keep individual differences in mind. Children develop fundamental motor skills at different rates, and not all children may have had exposure at home or in their communities to develop these skills (Bolger et al., 2021; Goodway & Branta, 2003; Goodway et al., 2010). Considering ways that all children can participate by using the skills they currently have is important for engaging everyone. For example, in a tossing game, some children might be encouraged to toss items underhanded into a large hoop, while others toss into a smaller bin, still others might be encouraged to toss overhanded, with their non-dominant arm, or to toss/drop/kick items into a bin from a closer distance. In this manner, everyone is engaged at their own level and pushing their skills forward incrementally. In a movement and literacy game in which teachers show signs with words informing children how to move, teachers can include the words for various movements in the home languages represented in their class and encourage children to use the words as they hop (English), saltan (Spanish), and sautent (French).

Developing a culturally-responsive understanding of child development is essential to ensuring positive development for all children and extinguishing inappropriate classification of child movement behaviors as negative. Indeed, the behavior of children of color and those presenting or socialized as boys is often mislabeled as challenging, aggressive, and negative (Gilliam, 2005; Gilliam & Reyes, 2018) though their behavior may reflect typical active exploration and engagement of children their age. Children from these groups are more often withheld from opportunities for movement and energetic play than their white peers, further contributing to challenging behaviors and inequities. They are also suspended or expelled from early childhood classrooms at a higher rate, typically due to behavior challenges, and are more often labelled as aggressive and disrespectful. Teachers can be proactive in two ways to alleviate these negative outcomes: first by identifying children’s energetic movement as a biological need for movement and second by preparing active learning experiences that offer all children opportunities for movement and promote self-regulation. When teachers incorporate opportunities for movement, they cultivate a classroom that supports all children’s self-regulation and attention by allowing children to expend excess energy and thus, better regulate their emotions and focus their attention. Recent research engaging a diverse group of 3–5-year-old children in active lessons found children to better focus on seated tasks after engagement in the physically active learning experience (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b).

Opportunities to move throughout the day are also inclusive for children with visible and invisible disabilities. Children with attentional difficulties and intellectual disabilities (e.g., ADHD, Autism, Down’s Syndrome) as well as physical disabilities (e.g., Cerebral Palsy) benefit from regular movement both for their physical and psychosocial development (Hinckson & Curtis, 2013). Overall, the activities we have laid out in Table 2 can be performed by children regardless of ability or skill level with appropriate adaptations, and children with Down’s Syndrome and Autism have previously participated in these activities (McGowan et al., 2020, 2021b). Like all learning experiences, teachers must ensure the game can be adapted to engage children with different mobility needs. For example, teachers should provide enough space for each child’s movement including children using a walker or wheelchair, who may need a larger turning radius to participate. Teachers can also adapt throwing activities to be kicking activities, or vice-versa, for children with minimal use of their upper or lower limbs. It is important for teachers to leverage children’s interests, experiences, culture, and language to inform their opportunities for active play in school. In this way, teachers can use physical activity in their classroom as a way to be culturally-responsive and inclusive of diverse learners (Patel & Travers, 2021).

Make Physical Activity a Way to Connect with Families

Family physical activity has an important influence on children’s health and wellbeing. Children with families who eat healthy foods and engage in movement tend to also participate in more physical activity (Kininmonth et al., 2021). Research highlights that family support of physical activity comes in the form of logistical and financial support (e.g., taking the child to sport lessons, purchasing a tricycle) and modeling (e.g., going on a walk with the child; Edwardson & Gorely, 2010). In addition, community resources make a difference for children’s opportunities for physical activity due to the walkability of the neighborhood, available green space and park equipment, and access to healthy foods. It is important for educators to recognize that many families, especially those identifying as members of marginalized communities, face numerous barriers to a healthy lifestyle, including heightened stress and anxiety due to systemic inequities and discrimination, long working hours, and scarcity of supermarkets and green space in their neighbourhoods (Leng et al., 2022).

Teachers can facilitate the physical health and wellbeing of the children and families they serve through home-school partnerships. Teachers can promote awareness to families of the importance of physical health through the communications they have with families and children. As with any part of the curriculum, teachers can share with families what they do in the classroom to support physical health and activity and explain why these opportunities are so important for children. Teachers can provide guidance to families about how to extend these learning opportunities at home.

Example

During a learning unit about how our bodies move, Dr. Kendall included in a family newsletter guidance for families to extend class discussions by helping children to label the parts of their own body and children’s movements (e.g., hop, skip, run, roll) in their home language. They/she/he/iel/ve also encouraged family activity by including reminders about how many hours of sleep and activity are recommended each day for young children like the image in Figure 1 (World Health Organization, 2019). They/she/he/iel/ve identified several ways families can be active together, like dancing together to their favorite music, taking a walk in their neighborhood, playing together at the local park, or doing some meditation and stretching to relax before bedtime. In addition, they/she/he/iel/ve invited families to share with the class a movement families enjoy together either by sending a video of their movement to Dr. Kendall or performing in the classroom together. This invitation yielded opportunities for children to learn about yoga, Tai Chi, limbo, soccer, bocce, and various forms of fun family dancing. This guidance can support families to identify and celebrate all forms of movement and engage families in physical activity with their child. In addition, Dr. Kendall positioned families as experts by inviting each family to share the unique ways they engage in movement together.

Teachers can further promote physical health of families by connecting them with community resources that facilitate activity. Teachers can share with families about the community resources available for being active including parks, sports fields, nature centers, pools, and the community center. Providing families with information about available classes or learning opportunities in these spaces can promote family involvement. In addition, local festivals often include opportunities for dance, active games, sports, or races for children, in addition to walking around the festival and being exposed to different forms of art and cultural experiences. Many local communities offer opportunities to see sports, dance, acrobatic, artistic, or theatric and cultural performances to inspire children’s interest in varied movements. It is important to include opportunities for which there are minimal barriers to access—including free admission, transportation or walkability, and multilingual information/signage to support all families to access these community resources (Gerde et al., 2021). In these ways, teachers can help children and families identify ways in which staying active connects them to their families and aligns with their purpose in life, which has shown to support daily wellbeing (Falk et al., 2015; McGowan, et al., 2022).

Conclusion

Integrating physical activity with instruction of core academic content is a powerful way to promote learning while simultaneously reducing time spent sedentary during the school day, improving children’s attention and self-regulation, and reducing disruptive behavior. Teachers can use the approaches listed in this article to promote children and families getting more active throughout the day. Using physical activity in the classroom can offer children low in self-regulation the boost they need to stay engaged in classroom activities and ensure they do not miss out on important learning opportunities. As educators, we have the responsibility to implement activities supporting energetic play in school to provide all children with the opportunity to practice and develop fundamental movement skills that encourage lifelong patterns of physical activity. To support wellbeing across the lifespan and address health inequities, prioritizing inclusive physical activity in schools is a robust means to diffuse public health programming that supports healthy active living behaviors for everyone.

References

Alhassan, S., Nwaokelemeh, O., Mendoza, A., Shitole, S., Whitt-Glover, M. C., & Yancey, A. K. (2012). Design and baseline characteristics of the Short bouTs of Exercise for Preschoolers (STEP) study. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 1–9.

Apache, R. R. G. (2005). Activity-based intervention in motor skill development. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 100(3_suppl), 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.100.3c.1011-1020

Bailey, A. W., Allen, G., Herndon, J., & Demastus, C. (2018). Cognitive benefits of walking in natural versus built environments. World Leisure Journal, 60(4), 293–305.

Bailey, D. P., Fairclough, S. J., Savory, L. A., Denton, S. J., Pang, D., Deane, C. S., & Kerr, C. J. (2012). Accelerometry-assessed sedentary behaviour and physical activity levels during the segmented school day in 10–14-year-old children: The HAPPY study. European Journal of Pediatrics, 171(12), 1805–1813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-012-1827-0

Barnett, E. Y., Ridker, P. M., Okechukwu, C. A., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2019). Integrating children’s physical activity enjoyment into public health dialogue (United States). Health Promotion International, 34(1), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dax068

Barnett, L. M., Stodden, D., Cohen, K. E., Smith, J. J., Lubans, D. R., Lenoir, M., Iivonen, S., Miller, A. D., Laukkanen, A., & Dudley, D. (2016). Fundamental movement skills: An important focus. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(3), 219–225.

Barnett, T. A., O’Loughlin, J. L., Gauvin, L., Paradis, G., Hanley, J., McGrath, J. J., & Lambert, M. (2009). School opportunities and physical activity frequency in nine year old children. International Journal of Public Health, 54(3), 150–157.

Becker, D. R., McClelland, M. M., Loprinzi, P., & Trost, S. G. (2014). Physical activity, self-regulation, and early academic achievement in preschool children. Early Education & Development, 25(1), 56–70.

Becker, D. R., & Nader, P. A. (2021). Run fast and sit still: Connections among aerobic fitness, physical activity, and sedentary time with executive function during pre-kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 57, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.04.007

Bertolero, M. A., Dworkin, J. D., David, S. U., Lloreda, C. L., Srivastava, P., Stiso, J., Zhou, D., Dzirasa, K., Fair, D. A., & Kaczkurkin, A. N. (2020). Racial and ethnic imbalance in neuroscience reference lists and intersections with gender. BioRxiv, 64, 583.

Bezerra, T. A., Clark, C. C. T., Filho, A. N. D. S., Fortes, L. D. S., Mota, J. A. P. S., Duncan, M. J., & Martins, C. M. D. L. (2020). 24-hour movement behaviour and executive function in preschoolers: A compositional and isotemporal reallocation analysis. European Journal of Sport Science. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1795274

Bolger, L. E., Bolger, L. A., O’Neill, C., Coughlan, E., O’Brien, W., Lacey, S., Burns, C., & Bardid, F. (2021). Global levels of fundamental motor skills in children: A systematic review. Journal of Sports Sciences, 39(7), 717–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1841405

Brown, W. H., Pfeiffer, K. A., McIver, K. L., Dowda, M., Almeida, J. M. C. A., & Pate, R. R. (2006). Assessing preschool children’s physical activity. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 77(2), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2006.10599351

Caplar, N., Tacchella, S., & Birrer, S. (2017). Quantitative evaluation of gender bias in astronomical publications from citation counts. Nature Astronomy, 1(6), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-017-0141

Cardinal, B. J. (2001). Role modeling attitudes and physical activity and fitness promoting behaviors of HPERD professionals and preprofessionals. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 72(1), 84–90.

Carson, V., Ezeugwu, V. E., Tamana, S. K., Chikuma, J., Lefebvre, D. L., Azad, M. B., Moraes, T. J., Subbarao, P., Becker, A. B., Turvey, S. E., Sears, M. R., & Mandhane, P. J. (2019). Associations between meeting the Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years and behavioral and emotional problems among 3-year-olds. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 22(7), 797–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.01.003

Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E., & Christenson, G. M. (1985). Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Reports, 100, 126–131.

Chakravartty, P., Kuo, R., Grubbs, V., & McIlwain, C. (2018). # CommunicationSoWhite. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy003

Cheung, P. (2020). Teachers as role models for physical activity: Are preschool children more active when their teachers are active? European Physical Education Review, 26(1), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19835240

Clevenger, K. A., McKee, K. L., & Pfeiffer, K. A. (2021). Classroom location, activity type, and physical activity during preschool children’s indoor free-play. Early Childhood Education Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01164-7

Cliff, D. P., McNeill, J., Vella, S. A., Howard, S. J., Santos, R., Batterham, M., Melhuish, E., Okely, A. D., & de Rosnay, M. (2017). Adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years and associations with social-cognitive development among Australian preschool children. BMC Public Health, 17(5), 857. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4858-7

Coe, D. P. (2020). Means of optimizing physical activity in the preschool environment. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 14(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827618818419

Davidson, M. C., Amso, D., Anderson, L. C., & Diamond, A. (2006). Development of cognitive control and executive functions from 4 to 13 years: Evidence from manipulations of memory, inhibition, and task switching. Neuropsychologia, 44(11), 2037–2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.02.006

Dinkel, D., Schaffer, C., Snyder, K., & Lee, J. M. (2017). They just need to move: Teachers’ perception of classroom physical activity breaks. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 186–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.020

Dion, M. L., Sumner, J. L., & Mitchell, S. M. (2018). Gendered citation patterns across political science and social science methodology fields. Political Analysis, 26(3), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.12

Dishman, R. K., Sallis, J. F., & Orenstein, D. R. (1985). The determinants of physical activity and exercise. Public Health Reports, 100(2), 158.

Dworkin, J. D., Linn, K. A., Teich, E. G., Zurn, P., Shinohara, R. T., & Bassett, D. S. (2020). The extent and drivers of gender imbalance in neuroscience reference lists. Nature Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-0658-y

Edwardson, C. L., & Gorely, T. (2010). Parental influences on different types and intensities of physical activity in youth: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(6), 522–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.05.001

Faith, M. S., Van Horn, L., Appel, L. J., Burke, L. E., Carson, J. A. S., Franch, H. A., Jakicic, J. M., Kral, T. V., Odoms-Young, A., & Wansink, B. (2012). Evaluating parents and adult caregivers as “agents of change” for treating obese children: Evidence for parent behavior change strategies and research gaps: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 125(9), 1186–1207.

Falk, E. B., O’Donnell, M. B., Cascio, C. N., Tinney, F., Kang, Y., Lieberman, M. D., Taylor, S. E., An, L., Resnicow, K., & Strecher, V. J. (2015). Self-affirmation alters the brain’s response to health messages and subsequent behavior change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(7), 1977–1982. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1500247112

Fulvio, J. M., Akinnola, I., & Postle, B. R. (2021). Gender (im) balance in citation practices in cognitive neuroscience. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 33(1), 3–7.

Gerde, H. K., Pikus, A. E., Lee, K., Van Egeren, L. A., & Quon Huber, M. S. (2021). Head start children’s science experiences in the home and community. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 54, 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.09.004

Gilliam, W. S. (2005). Prekindergarteners left behind. Expulsion rates in stat prekindergarten systems

Gilliam, W. S., & Reyes, C. R. (2018). Teacher decision factors that lead to preschool expulsion: Scale development and preliminary validation of the preschool expulsion risk measure. Infants & Young Children, 31(2), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0000000000000113

Goodway, J. D., & Branta, C. F. (2003). Influence of a motor skill intervention on fundamental motor skill development of disadvantaged preschool children. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 74(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2003.10609062

Goodway, J. D., Robinson, L. E., & Crowe, H. (2010). Gender differences in fundamental motor skill development in disadvantaged preschoolers from two geographical regions. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 81(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2010.10599624

Government of Canada, P. S. & P. C. (2022, September 14). Inclusive writing – Guidelines and resources – Writing Tips Plus – Writing Tools – Resources of the Language Portal of Canada – Canada.ca. https://www.noslangues-ourlanguages.gc.ca/en/writing-tips-plus/inclusive-writing-guidelines-resources

Guirguis, R. (2018). Should we let them play? Three key benefits of play to improve early childhood programs. International Journal of Education and Practice, 6(1), 43–49.

Harbin, S. G., Davis, C. A., Sandall, S., & Fettig, A. (2022). The effects of physical activity on engagement in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(8), 1461–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01272-4

Hauck, J. L., Pasik, P. J., & Ketcheson, L. R. (2021). A-ONE - An accessible online nutrition & exercise program for youth with physical disabilities. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 111, 106594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2021.106594

Head Start Resource Center. (2010). The Head Start child development and early learning framework (no. HHSP233201000415G). Office of Head Start, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Helgerud, J., Høydal, K., Wang, E., Karlsen, T., Berg, P., Bjerkaas, M., Simonsen, T., Helgesen, C., Hjorth, N., & Bach, R. (2007). Aerobic high-intensity intervals improve V˙ O2max more than moderate training. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(4), 665–671.

Hillman, C. H., Logan, N. E., & Shigeta, T. T. (2019). A review of acute physical activity effects on brain and cognition in children. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine, 4(17), 132. https://doi.org/10.1249/TJX.0000000000000101

Hinckson, E. A., & Curtis, A. (2013). Measuring physical activity in children and youth living with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(1), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2012.07.022

Hooker, S. A., & Masters, K. S. (2016). Purpose in life is associated with physical activity measured by accelerometer. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(6), 962–971.

Hooker, S. A., & Masters, K. S. (2018). Daily meaning salience and physical activity in previously inactive exercise initiates. Health Psychology, 37(4), 344.

Housman, D. K. (2017). The importance of emotional competence and self-regulation from birth: A case for the evidence-based emotional cognitive social early learning approach. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 11(1), 1–19.

Howie, E. K., Beets, M. W., & Pate, R. R. (2014). Acute classroom exercise breaks improve on-task behavior in 4th and 5th grade students: A dose–response. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 7(2), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2014.05.002

Howie, E. K., Schatz, J., & Pate, R. R. (2015). Acute effects of classroom exercise breaks on executive function and math performance: A dose-response study. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 86(3), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2015.1039892

Hulteen, R. M., Morgan, P. J., Barnett, L. M., Stodden, D. F., & Lubans, D. R. (2018). Development of foundational movement skills: A conceptual model for physical activity across the lifespan. Sports Medicine, 48(7), 1533–1540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-0892-6

Isenberg, J. P., & Quisenberry, N. (2002). A position paper of the Association for Childhood Education International PLAY: Essential for all Children. Childhood Education, 79(1), 33–39.

Ketcheson, L., Felzer-Kim, I. T., & Hauck, J. L. (2021). Promoting adapted physical activity regardless of language ability in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 92(4), 813–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2020.1788205

Kininmonth, A. R., Smith, A. D., Llewellyn, C. H., Dye, L., Lawton, C. L., & Fildes, A. (2021). The relationship between the home environment and child adiposity: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01073-9

Leerkes, E. M., Paradise, M., O’Brien, M., Calkins, S. D., & Lange, G. (2008). Emotion and cognition processes in preschool children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54, 102–124.

Leng, J., Lui, F., Narang, B., Puebla, L., González, J., Lynch, K., & Gany, F. (2022). Developing a culturally responsive lifestyle intervention for overweight/obese U.S. Mexicans. Journal of Community Health, 47(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-01016-w

Logan, S. W., Robinson, L. E., Wilson, A. E., & Lucas, W. A. (2012). Getting the fundamentals of movement: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of motor skill interventions in children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(3), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01307.x

Ludwig, K., & Rauch, W. A. (2018). Associations between physical activity, positive affect, and self-regulation during preschoolers’ everyday lives. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 15, 63–70.

Mahar, M. T. (2011). Impact of short bouts of physical activity on attention-to-task in elementary school children. Preventive Medicine, 52, S60–S64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.026

Maliniak, D., Powers, R., & Walter, B. F. (2013). The gender citation gap in international relations. International Organization, 67(4), 889–922. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818313000209

Mandigo, J., Francis, N., Lodewyk, K., & Lopez, R. (2009). Physical literacy for educators. Physical and Health Education Journal, 75(3), 27–30.

Martyn, L. (2021). Mandated to move: Teacher identified barriers, facilitators, and recommendations to implementing daily physical activity

Mavilidi, M.-F., Okely, A. D., Chandler, P., Cliff, D. P., & Paas, F. (2015). Effects of integrated physical exercises and gestures on preschool children’s foreign language vocabulary learning. Educational Psychology Review, 27(3), 413–426.

Mavilidi, M.-F., Okely, A. D., Chandler, P., & Paas, F. (2016). Infusing physical activities into the classroom: Effects on preschool children’s geography learning. Mind, Brain, and Education, 10(4), 256–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12131

Mavilidi, M.-F., Okely, A. D., Chandler, P., & Paas, F. (2017). Effects of integrating physical activities into a science lesson on preschool children’s learning and enjoyment. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 31(3), 281–290.

Mavilidi, M.-F., Okely, A., Chandler, P., Domazet, S. L., & Paas, F. (2018). Immediate and delayed effects of integrating physical activity into preschool children’s learning of numeracy skills. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 166, 502–519.

McClelland, M. M., & Cameron, C. E. (2012). Self-regulation in early childhood: Improving conceptual clarity and developing ecologically valid measures. Child Development Perspectives, 6(2), 136–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00191.x

McGowan, A. L., Ferguson, D. P., Gerde, H. K., Pfeiffer, K. A., & Pontifex, M. B. (2020). Preschoolers exhibit greater on-task behavior following physically active lessons on the approximate number system. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13727

McGowan, A. L., Gerde, H. K., Pfeiffer, K. A., & Pontifex, M. B. (2021a). Meeting 24-hour movement behavior guidelines in young children: Improved quantity estimation and self-regulation. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/34v8w

McGowan, A. L., Gerde, H. K., Pfeiffer, K. A., & Pontifex, M. B. (2021b). Physically active learning in preschoolers: Improved self-regulation, comparable quantity estimation. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 22, 100150.

McGowan, A. L., Boyd, Z. M., Kang, Y., Bennett, L., Mucha, P., Ochsner, K. N., Bassett, D. S., Falk, E., & Lydon-Staley, D. M. (2022). Network Analysis of within-person temporal associations among physical activity, sleep, and wellbeing in situ. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/q4jn3

McGowan, A. L., Gerde, H. K., Pfeiffer, K. A., & Pontifex, M. B. (2022). Meeting 24-hour movement behavior guidelines in young children: Improved quantity estimation and self-regulation. Early Education and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2022.2056694