Abstract

Parent–teacher meetings are an important element of preschool education. Parents of children with disabilities especially show a high need for counseling, particularly at their child's transition to school. How preschool teachers address this need in their meetings with parents is heavily influenced by how they perceive their relationship with parents. This study, therefore, investigates how preschool teachers (n = 22) perceive their relationship with parents of children with disabilities in transition-related meetings. The data were collected in guideline-based interviews and analyzed using qualitative content analysis. The results show that most teachers think their own perspective on the child is more accurate than the parents’ perspective. Parents are predominantly seen as needing support. Furthermore, the teachers’ statements indicate that the children are rarely directly involved in the meetings. The teachers justify this with the children’s disabilities, for example. Overall, the findings suggest that an ‘educational partnership’ is not realized in meetings with parents of children with disabilities. The findings also imply that the concept of ‘educational partnerships’ is a questionable construct when adequately describing the relationship between parents and preschool teachers. In conclusion, the concept of educational alliances is presented as an alternative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A trustful relationship between parents and preschool teachers is considered a key prerequisite for successful inclusion at the preschool level (Cross et al., 2004). Hence when it comes to providing a high-quality educational environment for children with disabilities, the relationship between parents and preschool teachers is essential (Beneke & Cheatham, 2016). That relationship is also key to making the transition to primary school an inclusive process: in a concept of transitions based on ecological system theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), parents are relevant actors in the transition as parent involvement moderates the successful transition process for all children, including those with disabilities (Then & Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). To facilitate inclusive educational trajectories, it is also important how preschool teachers subjectively construct their relationship with parents (Zulauf & Zinsser, 2019), including those parents of children with disabilities. However, research on this topic has been very limited. In this study, we therefore concentrate on how preschool teachers perceive their relationship with parents of children with disabilities during the transition to school. The emphasis is on their perception in transition-related parent meetings, as parent meetings are the most common and most direct type of parent–teacher interaction. In this context, we strive to clarify two main questions: First, we investigate how preschool teachers perceive their relationship with parents of children with disabilities in transition-related parent meetings, i.e., what roles teachers do attribute to themselves as well as to the parents in the meetings and to what extent the teachers do differ in terms of their role attributions? Second, we examine to what extent preschool teachers do involve children with disabilities in these meetings as the children are the main transition actors. Following the World Health Organization’s (2001) definition of disability, the term ‘children with disabilities’ is used hereafter to refer to children who experience long-term restrictions in participating in general education settings because of their physical, mental, and/or emotional exceptionalities. The focus is on children with disabilities attending mainstream preschools (with and without an inclusion program). Our frame of reference is the discussion on the concept of ‘educational partnerships’, which has been very influential in the international discourse and is outlined in the following. In doing so, we report empirical findings that are relevant in the debate addressing the ‘educational partnerships’ ideal and identify weaknesses the concept shows in the light of these findings. On this base, we derive the research need and research questions of our study. Afterwards, we report the methods and results of our study. We conclude by discussing the question how appropriate the ideal of ‘educational partnerships’ is to characterize the relationship between parents and preschool teachers considering our findings.

Review of the Literature

Whereas the importance of the parent–teacher relationship is well-founded in theory and largely undisputed, the question of what exactly should characterize that relationship remains controversial. In education policy (e.g., in Germany: JFMK & KMK, 2022; in USA: National PTA, 2021), the ideal of ‘educational partnerships’ has become the standard. According to that ideal, a productive parent–teacher relationship is one of equal partners, with both groups pursuing the same goals and sharing institutional power (Betz, 2015). In this setup, communication between parents and teachers is deemed crucial (Zehbe & Sonnenberg, 2021). Parent–teacher meetings (i.e., conversations between parents and teachers about the child) are seen as key settings for cultivating that partnership in practice (Karila, 2006). They are, therefore, considered important contexts for developing parent–teacher partnerships. Consequently, such meetings are also important for the interactions between preschool teachers and parents of children with disabilities (Didenko & Frantseva, 2016).

Within the professional literature, by contrast, the concept has also seen some criticism. Based on a synopsis of international research, Betz et al. (2017) identify four general points of criticism regarding the ideal of educational partnerships. In the following, we present these criticisms, relate them to the context of inclusion, and specify their implications for parent–teacher meetings at preschools.

-

(1)

The importance of the child in the parent–teacher relationship is often neglected in research on partnerships in the preschool sector. Studies explicitly addressing the role of the child are quite rare. Furthermore, the available evidence suggests that the logic of generational hierarchies heavily dominates the meetings, with the adults describing themselves as the primary actors in the conversation and children having to play a subordinate role (Alasuutari & Markström, 2011). The same finding emerges even if children are directly involved in the meeting and if the focus is on the child’s perspective. Menzel (2022), for example, shows that children predominantly see themselves as passive recipients during the conversations, whereas the adults (parents, preschool teachers) are seen as the conversation leaders. This means that children are neglected not only in the research on parent–teacher meetings. Insufficient child involvement must also be assumed to characterize the meetings in practice.

-

(2)

The ‘partnership rhetoric’ inherent in the ‘educational partnerships’ concept obscures the fact that the dominant view among both policymakers and preschool/primary school teachers on certain groups of parents is one focused on deficits. Especially when it comes to parents of children facing structural educational disadvantages (e.g., children with a migration background), a deficit-oriented perspective prevails. As previous research has shown, deficit-oriented assumptions are also found in the relationship between preschool teachers and parents of children with disabilities. For example, there is evidence suggesting that parents of children with disabilities sometimes get the impression that teachers think of them as neglectful and hence feel obligated to proactively improve their relationship with the teachers (Roth & Faldet, 2020). Parents are thus directly exposed to the teachers’ deficit-oriented perspective.

-

(3)

In the concept of ‘educational partnerships’, the quality of parent–teacher interactions is measured by the degree to which these interactions are marked by partnership. However, whether partnership is in fact the most effective type of relationship in educational settings is questionable. There is a general lack of empirical evidence to support the assumption that partnership between parents and teachers—i.e., a relationship among equals that includes sharing institutional power—is most beneficial for everyone involved (Betz et al., 2017). At the same time, research findings point to the uncertainties that parents of children with disabilities experience regarding their children’s educational biography (e.g., transition to school) (McIntyre et al., 2010). Likewise, there is evidence (Dorrance, 2010) that parents of children with disabilities have a high need for support at various points in their children’s educational biographies (e.g., before starting school). The role of teachers here would be to meet parents’ needs and reduce uncertainty by providing professional expertise to parents and supporting them from this superior position. Whether a strictly partnership-based relationship in the sense of an equal parent–teacher relationship would be feasible and at all productive in this context is doubtful.

-

(4)

The ideal of ‘educational partnerships’ suggests that parents and preschool teachers are equals but negates the structural inequalities in the relationship between the two groups. Research on parent–teacher meetings at preschools shows that the relationship between parents and teachers in these meetings is mostly asymmetrical, with teachers usually dominating the conversations (Cheatham & Ostrosky, 2009; Cloos et al., 2013; Karila, 2006). Kesselhut (2015) identifies parent–teacher meetings in this context as being ‘places where difference is created’, as teachers tend to draw a line between themselves (as experts) and parents (as non-experts). Occasionally, parents are also found to dominate the meetings—at least at some points during the conversation (Markström, 2011). Partnership-based—meaning de facto equal—parent–teacher relationships are sometimes found (Plehn, 2012), but they are not the rule. In the meetings, teachers thus predominantly act as experts, which, after all, is the counseling role defined for them in educational policy. However, they hardly seem to be able to fulfill the competing demand placed on them by the concept of ‘educational partnerships’, namely to involve parents as equal partners in the counseling process (Betz et al., 2021). Little evidence is available on the relationship between preschool teachers and parents of children with disabilities in the meetings. However, Zehbe’s (2021) findings show that teachers’ normative expectations about child development play a significant role in the conversations, suggesting that the teachers’ perspective is very influential.

Research Need and Research Questions

As previous research has shown, the ideal of ‘educational partnerships’ has conceptual weaknesses—also and especially when it comes to the relationship between preschool teachers and parents of children with disabilities. However, further findings that would allow for more specific statements in this regard are scarce. More research is needed especially regarding preschool teachers’ subjective perceptions of their relationship with parents in parent–teacher meetings, as such meetings are one of the most direct forms of parent–teacher interaction. Consequently, we do not know much about the roles that preschool teachers attribute to themselves and to parents of children with disabilities in the context of these meetings. At the same time, evidence suggests that how teachers perceive their relationship to parents strongly influences whether teachers exclude the children of these parents from educational opportunities in the preschool setting. For example, relationships perceived as negative by teachers have been shown to be associated with a higher likelihood of exclusion (Zulauf & Zinsser, 2019). Preschool teachers’ perception of their relationship with parents is thus significant in pedagogical practice. Since children with disabilities are at higher risk of exclusion in the preschool sector (Zeng et al., 2021), a special focus on parents of children with disabilities is required at this point.

Against this background, the present study is designed to investigate how preschool teachers perceive their relationship with parents of children with disabilities in parent–teacher meetings. The focus is on conversations about the transition to school, as the transition to school is a key biographical milestone involving increased risks of selection (Crosnoe & Ansari, 2016), therefore putting children with disabilities at an especially high risk of exclusion. With this in mind, we derived the following questions for our study:

-

(1)

How do preschool teachers perceive their relationship with parents of children with disabilities in transition-related parent–teacher meetings?

-

(a)

What roles do teachers attribute to themselves in the meetings?

-

(b)

What roles do teachers attribute to parents in the meetings?

-

(c)

To what extent do teachers vary in their role attributions?

-

(a)

In the discussion about educational partnerships, child involvement is considered an important but often neglected issue (Betz et al., 2017). Therefore, our additional aim is to clarify:

-

(2)

To what extent do preschool teachers involve children with disabilities in transition-related meetings?

Methods

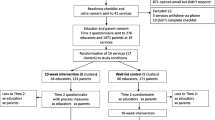

Sample

The sample of the present study comprises n = 22 preschool teachers from preschools in southern Germany. The average age is M = 42.64 years (min.: 25; max.: 64), the average work experience is 15.25 years. 20 of the 22 preschool teachers are female. Five teachers hold additional qualifications specific to inclusion (e.g., inclusion specialist). All teachers were lead teachers at a preschool at the time of the survey or in the past and had experiences in the institutional care of children with disabilities.

The sample was generated based on a qualitative sampling plan (Döring & Bortz, 2016) using the ‘criterion sampling’ method (Moser & Korstjens, 2018). In this process, respondents are selected according to some pre-established criteria of importance. The aim is to ensure the sample includes a variance of theoretically relevant features. Based on these features, a crosstabulation is created that reflects different combinations of features. The aim is not to make the sample representative but rather to include every possible combination of the theoretical relevant features. Each combination should therefore be assigned to at least one respondent. For our study, we defined three sampling criteria:

-

(1)

Professional experience of preschool teachers. As previous research has shown, the level of preschool teachers’ professional experience is linked to their attitudes toward inclusion. It is only the type of link that has yet to be finally determined: some studies find positive (Emam & Mohamed, 2011), others negative relationships (Kim et al., 2020). In addition, preschool teachers’ professional experience is relevant to their relationships with parents. Ward (2018) reports that more experienced preschool teachers are more satisfied with their own parent interactions.

-

(2)

Educational profile of the preschool where teachers work (inclusive vs. non-inclusive). Warren et al. (2016) show that working in a preschool with a specific inclusive profile can be associated with more intense communication between actors, including parent–teacher communications. The institution’s profile may thus be relevant for the quality of parent–teacher interactions. Moreover, inclusive preschools are characterized by smaller care groups (Smidt, 2008), suggesting that teachers in inclusive preschools can provide more individualized care.

-

(3)

Location of preschool (in the district of a school with an inclusive profile vs. not in the district of a school with an inclusive profile). In Germany, schools with an inclusive profile receive additional resources, such as special education teachers. Access to these resources is a major factor in parents’ school choices (Hirner, 2012) and, thus, also in transition-related counseling. Since school choice was addressed in the parent–teacher meetings, this point was also considered.

Table 1 provides an overview of the distribution of the sample across the different feature combinations.

Data Collection

The data were collected between October 2021 and June 2022 through qualitative, semi-structured guideline-based interviews (Kallio et al., 2016). The interviews lasted approximately 80 minutes on average (min: 60; max: 140).

The interview guide consisted of four thematically related blocks covering the following key aspects:

-

Preschool teachers’ understanding of the construct ‘disability’ in preschool children.

-

(Organizational-formal) Process of transition-related counseling meetings with parents of children with disabilities.

-

Decision-making of preschool teachers when recommending suitable school types for children with disabilities (mainstream primary school vs. special education institution).

-

Cooperation of preschool teachers in the context of transition to school of children with disabilities, including but not limited to cooperation with parents and interaction with the child.

For the present sub-study, we primarily considered data collected in the context of blocks two and four.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using thematic and type-building qualitative content analysis methods (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2022). To answer our research questions, we opted for a two-step procedure.

In the first step, we performed a deductive-inductive analysis of the data with a focus on organizational-formal design of the meetings and cooperation. The coding system that emerged in this way includes categories on the roles that teachers attribute to themselves in the meetings (research question 1a), the roles that teachers ascribe to parents in the meetings (research question 1b), and teachers’ perspectives on child involvement in the meetings (research question 2). Using that coding system, the data were analyzed by two independent coders. To ensure intersubjective validity, validation meetings were held after coding the third interview and the tenth interview, examples of deviations in the coding were discussed, and the coding system was refined as the coding proceeded. After the two validation meetings, the coding of the previously analyzed interviews was adapted to the refined coding system by both coders. After coding the entire material, a third validation meeting was held, and the coding system was finalized. In this way, the intercoder reliability of the codings could be gradually improved until a good score (Cohen’s kappa = 0.86) was available for the total number of all codings.

To be able to identify systematic differences between the surveyed preschool teachers and their role attributions (research question 1c), we performed a second, inductive step to construct polythetic types, i.e., groups of individuals that are as similar as possible but not necessarily identical (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2022). For this purpose, we defined a property space based on the results of the first analytical step (research questions 1a and 1b). This included, on the one hand, the roles that teachers attribute to themselves and, on the other hand, the roles that teachers attribute to parents. We noted whether or not a teacher attributes the respective role to themselves or to the parents (dichotomy: yes/no). Next, we constructed types using hierarchical cluster analysis (Kuckartz, 2010). For this purpose, we created a similarity matrix showing the simple agreement of all respondents in all features (i.e., mentioning or not mentioning the individual roles). For the next steps, we applied Johnson’s (1967) ‘maximum method’, as it does not require an interval scale level and is suitable for analyzing qualitative data (Kuckartz, 2010). We tested a two-cluster, three-cluster, four-cluster, and five-cluster solution, with the three-cluster solution emerging as the most feasible and most appropriate in terms of content. Therefore, the three-cluster solution was retained and used to derive three counseling types, which form the typology of the present study.

Results

Research Question 1a: Roles of Preschool Teachers

In the statements of the preschool teachers, we identified five roles that the teachers attribute to themselves. One teacher consistently named multiple roles she/he assumes in the meetings. The roles imply in parts more active, in parts more passive behavior towards the parents. The role attributions may, therefore, be placed on a continuum between ‘passivity’ and ‘activity’:

-

(1)

Teachers as recipients. In a few cases, teachers reported perceiving themselves as recipients in the meetings, meaning they must absorb information about the child for conducting the meeting in a professional manner. For example, teachers said they use parent meetings as an opportunity to expand their own expertise (about the child):

Teacher [T]: [...] The kids are totally different at home and in preschool. Sometimes I don’t really judge a child correctly, right? And then through these parent meetings, I understand better where the child needs me or where their needs are. (I_01182022_1, pos. 71)Footnote 1

Teachers call it their responsibility to generate knowledge (about the child). They thus assume a passive role.

-

(2)

Teachers as supporters. Teachers emphasized that they see the meetings, or themselves in the meetings, as helping the parents. For example, they see themselves as a source of information for the parents or as a support system to help the parents cope with specific tasks:

T: [...] So to me, to us or to me, it was always important to have a trustful relationship with the parents [...]. And then to quite clearly, and then to weigh, yes, and to help parents make a decision, yes. (I_02172022, pos. 399)

The role of the teacher, therefore, is to provide active support. In doing so, they do not think their own activities or opinions are more important or valid than those of the parents. Instead, the teachers try to complement the parents’ actions in a meaningful way and to contribute to their success.

-

(3)

Teachers as equal partners. Teachers emphasized interacting with parents as equal partners in the meetings—working with the parents to find the best solution for the child, for example:

T: [...] And that means really having a conversation. That we keep talking to each other and then really find a common ground together and see: Okay, this is what the kid is about, that’s how it is. And that’s what the kid needs. (I_01182022_2, pos. 34)

This role represents a true partnership between parents and teachers, as implied by the concept of ‘educational partnerships’ (see section ‘Review Of The Literature’).

-

(4)

Teachers as experts. Teachers emphasized their own expertise or the value of their own expertise in the meetings. By doing so, they made clear they believe their own expertise has priority over what parents may think:

T: [...] Sometimes the parents are blind or refuse to see things. We observe the kids, we keep observation sheets. We can then tell the parents, ‘Look, this where the kids are at.’ There are also, if I say: the parents are blind sometimes. Sometimes the kids, the parents don’t see what the kids are really capable of. That also happens. [...] Where the parents exaggerate and say, ‘No, no, no. The child does not hear. And from the side not at all. So you have to speak to the child face to face.’ And it’s things like that where you say, ‘Oh yes, the child does turn to me. And then I can talk to the child,’ right? (I_01182022_2, pos. 31–32)

Teachers thus construct a hierarchy of perspectives, prioritizing their own view over the parents’ view. However, they do not explicitly state that they want to convince the parents of their own view.

-

(5)

Teachers as advocates for the child. Teachers stated they want to push for the best possible outcome for the child, even against resistance, including the parents’ will. Again, the underlying assumption is that their own perspective (e.g., on the child) is more accurate and therefore more adequate than the parents’ perspective. In addition, teachers made it clear that they want to convince the parents of what they consider the best solution for the child (e.g., the most suitable type of school):

T: [...] And if the family believes it will definitely be a mainstream school, but all preschool teachers or therapists in the room think differently, then there is need to apply some persuasion. (I_02102022_1, pos. 46)

Research Question 1b: Roles of the Parents

Preschool teachers attributed five different roles to the parents as well. Again, statements by one teacher always contained multiple role attributions. The continuum between activity and passivity (of the parents towards the teachers) also exists here for most roles:

-

(1)

Parents as persons in need of support. Teachers clearly stated that parents need their support and that the primarily role of parents in the meeting therefore is to receive information or, more generally, support from the teacher:

Interviewer [I]: And what do you see as the task of the parents in such a counseling session?

T: [...] That they listen carefully to what we say, that is always important. Especially when you work with interpreters, which we frequently have to do. [...] Um, yes, and just working together, you know, that they are willing to listen to us [...]. (I_02212022, pos. 55–56)

According to that view, the parents’ responsibility in the meetings is to be open-minded, to listen and, if necessary, to accept support or advice from the teacher. Parents are thus perceived to be in a primarily passive role.

-

(2)

Parents as equal partners. Teachers emphasized that they see parents as equal partners in the meetings and that teachers and parents act in concert when seeking a solution for the child (see also section ‘Roles of preschool teachers’, number 3). This role attribution reflects a true partnership between parents and teachers, as implied by the concept of ‘educational partnerships’ (see section ‘Review of the literature’).

-

(3)

Parents as specialists for their child. Teachers emphasized that they believe parents have specific expertise about their child, for instance regarding the child’s disability:

T: [...] And the mother often has a much better view of what is special about this child than the person in charge. Also because she has known the child from the beginning and also knows it more intensively than we do. (I_01282022, pos. 14)

There is no, or less pronounced, hierarchization of perspectives here than in the role of the teacher as expert. Parent activity is, nonetheless, highlighted in this role attribution.

-

(4)

Parents as decision makers. Teachers emphasized that parents have powers of action that exceed their own authority and limit what they can do as teachers in the meetings. This includes, above all, the parents’ right to decide on the type of school for their child (mainstream school or special education school):

T: I mean/ I think the parents still make the decision in the end. I can lay out many things and say, ‘These are the options.’ But the bottom line is that parents can also say, ‘No, no, no, no. This is what I want.’ Which is a shame then, of course. But it’s their right. (I_02032022, pos. 40)

If the teachers gave reasons for parents’ decision-making power, they predominantly pointed to the (presumed) parental right to make these decisions. They rarely stated that the parents’ authority is justified by their specific knowledge or specific competencies as parents.

-

(5)

Parents as caregivers for their child. Teachers explicitly emphasized that, from their point of view, the primary role of parents is to be guided by the needs of the child and to work towards meeting the child’s needs. This general parental duty is reflected in the meetings or in the subsequent decision-making:

T: The parents, of course, have their child in mind. I think that’s the task, the duty of parents, to want the best for their child. And not to always look outward. [...] But to really look: What is best for my child? That is actually the duty of parents, to focus only on their child and to want the best for their child. (I_01182022_4, pos. 53–54)

Unlike the other role attributions, this role is not constructed through the parents’ relationship with the teachers, but with the child. Therefore, parents are neither considered to play a primarily active nor a primarily passive role vis-à-vis the teachers.

Research Question 1c: Counseling Types

Three counseling types could be identified among the preschool teachers, that is, three types that differ systematically in terms of how they perceive their own role and the role of parents in the counseling process. These types are explained below.

Type 1: Prioritizing-Reciprocal Type

Preschool teachers of this type see themselves as ‘supporters’ in the counseling process (see section ‘Roles of preschool teachers’, number 2), but they also often emphasize the priority of their own—supposedly more accurate—view over the parents’ view (i.e., they act as ‘experts’ or ‘advocates for the child’). At the same time, these teachers show their willingness or need to receive information from the parents during the meetings to be able to use that knowledge in their further work (e.g., for counseling). Although these teachers prioritize their own perspective (e.g., on the child), they are interested in a reciprocal relationship with the parents, that is, a relationship in which they provide information to the parents but also receive information from the parents.

Parents are only partially perceived to be in an active role by teachers of this counseling type (e.g., as ‘decision makers’). In contrast, the (passive) role of parents as ‘persons in need of support’ is mentioned by all teachers. Although the teachers acknowledge the need to receive information from the parents, the parents are not considered to play a fully active part.

Type 2: Prioritizing-Offering Type

In addition to being ‘supporters’ (see section ‘Roles of preschool teacher’, number 2), teachers of this type often see themselves in roles that emphasize the priority of their own perspective over the parent perspective. The role of ‘expert’ is widespread, but several teachers also see themselves as ‘advocates for the child’. In contrast to the prioritizing-reciprocal type, teachers of this type rarely perceive themselves as ‘recipients’ in the counseling process. Hence, they rarely see the need to use the parents’ knowledge for their own activities. What these teachers do in their counseling is thus rather one-sided: they support the parents or present their own, (supposedly) more accurate perspective (e.g., on the child) to the parents, but they do not see the importance of receiving information from the parents. Thus, these teachers mainly offer information without showing a desire to acquire knowledge from the parents and to use it for counseling.

Even if teachers of this type are not very eager to obtain knowledge from parents, and even if they all agree that parents need support, they do not automatically see parents as purely passive actors. Rather, they often see them in active roles (e.g., as ‘decision makers’).

Type 3: Offering-Cautious Type

Teachers of this type emphasize their own activity in the counseling process (especially as ‘supporters’), but unlike the teachers of the other two types, they rarely stress the priority of their own perspective. If they value their own perspective more than the parents’, they do so without trying to convince the parents of their own point of view, that is, without acting as ‘advocates for the child’. These teachers thus tend to be cautious in their counseling, on the one hand being aware of their own expertise and sometimes even believing it to be more accurate than the parents’ perspective, but on the other hand never acting against the parents’ will. Their relationship with parents is one-sided, as none of the teachers of this type mentions the necessity of receiving information from the parents. These teachers thus limit their activities to offering information.

Parents are widely seen in the role of ‘decision-makers’ but are also predominantly perceived as needing support. Only in a few cases do teachers see parents in active roles that are not related to parental decision-making authority (e.g., as ‘specialists for their child’).

The distribution of respondents across the three counseling types shows that most preschool teachers tend to value their own perspective more than the parents’ perspective: Nine teachers belong to type 1 (prioritizing-reciprocal type), nine to type 2 (prioritizing-offering type), and four to type 3 (offering-cautious type). At the same time, most teachers (types 1 and 2) generally see the possibility of acting as ‘equal partners’ with the parents from time to time (e.g., seeking solutions to specific questions, such as the most suitable type of school, together with the parents on an equal level).

Research Question 2: Child Involvement in the Meetings

Another focus of the study was on the extent to which preschool teachers reported child involvement in the transition-related meetings. The analysis show that teachers distinguish between actual involvement (i.e., occurring in practice) and potential involvement.

Only one teacher reported that the child was actually involved in a meeting devoted to transition to school. The more common practice is indirect involvement, meaning that even though the child itself does not participate in the meeting, the conversation is informed by what the child wants, or parents are called upon to involve their child in the decision-making:

T: The parents, if they want to, can of course also visit the schools beforehand. And I always find it important/ Well, I have already spoken with a few parents. That the parents possibly also visit the school with the kids beforehand and get them, well, a little excited about it, you know. So that the kids are also able to decide, ‘Okay, I can feel comfortable here.’ [...] (I_02032022, pos. 294)

Most often, teachers stated they explicitly do not involve the child in the meetings:

T: Well, not so much. Strangely enough, yes. You actually rather leave them that way/ You observe them. They are simply there for you to observe and to draw conclusions from this behavior and so on. That’s what you do, really. But I don’t think I’ve ever included them in the questioning. I can’t say, really. [...] (I_01252022, pos. 385–386)

The reason often given was that school choice is generally the parents’ responsibility. Teachers also pointed out that the child (in general and because of its disability) is not capable of making an adequate decision.

Not all preschool teachers commented on potential involvement. However, those who did agreed that the child should be more involved in the conversations and the transition decision, for instance ‘for reasons of participation’ (I_01182022_4, pos. 311). However, teachers who were especially strict in their rejection of actual child involvement did not consider potential child involvement either.

Discussion

Educational partnerships between preschool teachers and parents are widely considered an ideal in early childhood education and care and have become an education policy goal in several countries (e.g., Betz, 2015; Rouse & O’Brien, 2017). However, the extent to which partnership-based relationships—i.e., relationships among equals involving institutional power-sharing between preschool teachers and parents—are practically feasible and de facto desirable is controversial (Betz et al., 2020). Building on this discourse, the present study investigated how preschool teachers perceive their relationship with parents of children with disabilities in transition-related parent–teacher meetings. In the following, we connect our findings to that discourse and discuss them against the background of the criticisms that have been brought against the ideal of ‘educational partnerships’ (Betz et al., 2017).

-

(1)

Deficit-oriented perspective on parents? Unlike in earlier studies (Roth & Faldet, 2020), preschool teachers in our study did not perceive parents of children with disabilities as neglectful. A primarily deficit-oriented perspective on parents, possibly masked in a ‘rhetoric of partnership’, does not emerge for our sample. However, teachers in the present study strongly insisted that parents are in high need of support. This needs-oriented perspective is dominated by a mindset in which parents of children with disabilities need support, possibly more than parents of children without disabilities. Although this is certainly consistent with previous research (e.g., Dorrance, 2010), such a needs-oriented perspective may diminish teachers’ awareness of parents’ potential and resources—especially if parents are simultaneously expected to play only a limited active role (as seen by the teachers of the first and third counseling type). However, such an awareness would be crucial for a relationship based on equality and partnership.

-

(2)

Partnership as an ideal? Our results indicate that preschool teachers seek to convey their own professional opinions to parents in the meetings. This is consistent with earlier findings, which show that teachers frequently act as experts in parent meetings (e.g., Karila, 2006; Kesselhut, 2015). Moreover, all teachers pointed out that supporting parents is part of their counseling. Teachers, thus, tend to view parents as clients who need support while thinking of themselves as actors who provide support. Their support is based on a—to some extent—hierarchical relationship: the meetings are counseling situations in which the counselors (preschool teachers) have a knowledge advantage over those who get counseled (parents) (Plehn, 2012). This setup constitutes a power imbalance between teachers and parents, albeit certainly a legitimate one, given the preschool teachers’ educational policy mandate to serve as counselors. According to that mandate, preschool teachers are expected to create counseling situations for parents and to meet their need for counseling as counselors (with a knowledge advantage). However, it is questionable to what extent the call for an equal teacher-parent partnership can—and should—be implemented under these conditions. On the contrary, from the teachers’ point of view, partnership (understood as a strictly equal relationship) is a rather ineffective way of meeting parents’ need for support. Thus, the demand on teachers to support parents as counselors with professional expertise is difficult to reconcile with the demand to consistently interact with parents as equal partners (Betz et al., 2021). Accordingly, partnership appears to be less suitable as a primary indicator of the quality of the relationship.

-

(3)

Symmetrical relationship between parents and preschool teachers? Our findings do not indicate that preschool teachers generally view parents as equal partners in the meetings. On the contrary, our analysis of the different counseling types shows that teachers mostly think their own perspective is more accurate than the parents’ perspective. Teachers thus seem to draw a line between themselves as experts and parents as non-experts, providing support from that superior position. This is consistent with the pedagogical role defined for them in educational policy (see above). The analysis also shows that teachers do not think of their relationship with parents in the meetings as a symmetrical relationship. This is despite the fact that most teachers do see the possibility of (also) interacting with parents as equal partners. Consequently, that option was discussed less frequently in teachers’ statements. Likewise, the fact that teachers often see parents as the decision-makers and hence as playing an active role in the meetings does not mean that teachers perceive parents as equals. Thus, teachers rarely stated that parents’ decision-making power is justified by their specific knowledge of their child. Instead, it is conceivable that teachers accept parental authority mainly for formal reasons, such as applicable law. It seems doubtful that teachers consider such formal authority equivalent to their own authority, which is based on knowledge and professional competence. Overall, the findings suggest that parent–teacher meetings, for the most part, are not based on a symmetrical relationship: preschool teachers seem to think it is more important to fulfill their counseling responsibility than to meet the conflicting demand for strictly partnership-based relationships with parents. One reason could be the teachers’ abovementioned needs-oriented perspective on parents, which may make it seem more appropriate for them to support the parents with their professional expertise—and to accept the power imbalance implied in the counseling situation—than to seek a true educational partnership. Our findings are essentially consistent with previous studies that have found asymmetrical parent–teacher relationships in preschool settings (e.g., Einarsdottir & Jónsdóttir, 2019).

-

(4)

Child involvement in the meetings? Preschool teachers’ statements suggest that children with disabilities are rarely involved in parent–teacher meetings devoted to transition to school. To remedy this situation, it would be necessary for all actors in the educational process to explicitly address child involvement (Betz et al., 2020) and to give all actors responsibility for involving the child. To increase the involvement of children with disabilities in transition-related meetings, it is particularly important to also engage primary school teachers and service providers (e.g., therapists) next to preschool teachers and parents, as they are also relevant to making the transition to primary school successful for children with disabilities (Then & Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). Service providers (e.g., special needs educators) in particular can help inform the counseling process with their expertise about specific forms of disability and may help ensure that the specific features of individual disabilities are no longer seen as barriers to child involvement. Our study shows that preschool teachers disagree not only about actual child involvement but also about the need for child involvement. Promoting positive attitudes toward child involvement—for example, through training and professional development—would therefore be a starting point for increasing the degree to which children are involved in the meetings. Overall, we find room for improvement with respect to both actual and potential child involvement in parent–teacher meetings.

In summary, our findings show that a partnership-based relationship between preschool teachers and parents of children with disabilities in transition-related meetings does not exist and that teachers seem to consider a strictly equal relationship to be hardly effective. In line with previous studies (e.g., Betz et al., 2020), our study thus suggests that the concept of ‘educational partnerships’ as the ideal parent–teacher relationship is unsustainable in the preschool sector. Instead, it seems more appropriate to speak of educational alliances in which

-

all participants pursue the overriding goal of creating an educational process that is most beneficial for the child’s development. Aside from preschool teachers and parents, that alliance should include service providers, primary school teachers (if school- or transition-related issues are at stake), and—last but not least—the child itself;

-

the specific competencies of each party involved are taken into account and included in the interactions to address the tasks at hand;

-

the parties involved are not expected to be strictly equal in all kinds of interactions. Instead, the power structure should be viewed as flexible, and powers should be re-balanced between the actors in each interaction, depending on the situation.

Limitations and Outlook

The study presented here has various limitations. For example, our interviews only capture the perspectives of the preschool teachers, meaning our findings exclusively reflect the teachers’ subjective assessments. Further research might also consider the perspectives of parents, children, school teachers, and service providers (therapists, etc.) who also play a role in the transition process (Sands & Meadan, 2022; Then & Pohlmann-Rother, 2023). Moreover, further studies may want to include preschool teachers with additional, theoretically relevant features in their sample.

The aim of our study was to identify general tendencies in the teachers’ statements. In a next step, it may be useful to zoom in on individual teachers, for instance through individual case analyses.

Finally, our study offers starting points for further research. For example, further interview studies might help expand the knowledge on the topic with more in-depth analyses. Likewise, quantitative studies examining correlations (e.g., between role attributions and a preschool teacher’s job-related beliefs) or the scope of the findings would be informative.

Data Availability

The data of the present study are interview transcripts and not available for the public.

Notes

The interviews were conducted in German and completely transcribed verbatim. The present excerpts were translated in English as verbatim as possible.

References

Alasuutari, M., & Markström, A.-M. (2011). The making of the ordinary child in preschool. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 55(5), 517–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.555919

Beneke, M. R., & Cheatham, G. A. (2016). Inclusive, democratic family-professional partnerships: (Re)Conceptualizing culture and language in teacher preparation. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35(4), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121415581611

Betz, T. (2015). The ideal of educational partnerships: A critique of the current debate on cooperation between ECEC centers, primary schools and families. Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Betz, T., Bischoff, S., Eunicke, N., Kayser, L. B., & Zink, K. (2017). Partner auf Augenhöhe? Forschungsbefunde zur Zusammenarbeit von Familien, Kitas und Schulen mit Blick auf Bildungschancen. Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Betz, T., Bischoff-Pabst, S., Eunicke, N., & Menzel, B. (2020). Children at the crossroads of opportunities and constraints. Collaboration between early childhood education and care centers and families: Viewpoints and challenges. Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Betz, T., Bollig, S., Cloos, P., Krähnert, I., & Zehbe, K. (2021). Kinder, Eltern, pädagogische Fachkräfte: Programmatiken und Praktiken institutioneller Verhältnisverschiebungen zwischen Familie und Kindertageseinrichtungen. In Sektion Sozialpädagogik und Pädagogik der frühen Kindheit (Ed.), Familie im Kontext kindheits- und sozialpädagogischer Institutionen (pp. 85–99). Beltz Juventa.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 793–828). Wiley.

Cheatham, G. A., & Ostrosky, M. M. (2009). Listening for details of talk: Early childhood parent-teacher conference communication facilitators. Young Exceptional Children, 13(1), 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096250609347283

Cloos, P., Schulz, M., & Thomas, S. (2013). Wirkung professioneller Bildungsbegleitung von Eltern. In L. Correll & J. Lepperhoff (Eds.), Frühe Bildung in der Familie (pp. 253–267). Beltz Juventa.

Crosnoe, R., & Ansari, A. (2016). Family socioeconomic status, immigration, and children’s transition into school. Family Relations, 65(1), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12171

Cross, A. F., Traub, E. K., Hutter-Pishgahi, L., & Shelton, G. (2004). Elements of successful inclusion for children with significant disabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 24(3), 169–183.

Didenko, I. A., & Frantseva, E. N. (2016). Features of interaction between preschool teachers and “special” children and their parents. Procedia, 233, 459–462.

Döring, N., & Bortz, J. (2016). Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften (5th ed.). Springer.

Dorrance, C. (2010). Barrierefrei vom Kindergarten in die Schule? Klinkhardt.

Einarsdottir, J., & Jónsdóttir, A. H. (2019). Parent-preschool partnership: Many levels of power. Early Years, 39(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2017.1358700

Emam, M. M., & Mohamed, A. H. H. (2011). Preschool and primary school teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education in Egypt: The role of experience and self-efficacy. Procedia, 29, 976–985.

Hirner, V. (2012). Kinder mit Lernstörungen und Behinderungen in integrativen Schulen oder in Sonderschulen? [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Universitätsklinikum Ulm.

JFMK, & KMK (2022). Gemeinsamer Rahmen der Länder für die frühe Bildung in Kindertageseinrichtungen. Berlin.

Johnson, S. C. (1967). Hierarchical clustering schemes. Psychometrika, 32(3), 241–254.

Kallio, H., Pietilä, A.-M., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 2954–2965.

Karila, K. (2006). The significance of parent - practitioner interaction in early childhood education. Zeitschrift für qualitative Bildungs-, Beratungs- und Sozialforschung, 7(1), 7–24.

Kesselhut, K. (2015). Machtvolle Monologe. In P. Cloos, K. Koch, & C. Mähler (Eds.), Entwicklung und Förderung in der frühen Kindheit (pp. 207–222). Beltz Juventa.

Kim, S., Cambray-Engstrom, E., Wang, J., Kang, V. Y., Choi, Y.-J., & Coba-Rodriguez, S. (2020). Teachers’ experiences, attitudes, and perceptions towards early inclusion in urban settings. Inclusion, 8(3), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1352/2326-6988-8.3.222

Kuckartz, U. (2010). Einführung in die computergestützte Analyse qualitativer Daten (3rd ed.). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2022). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. Beltz Juventa.

Markström, A.-M. (2011). To involve parents in the assessment of the child in parent-teacher conferences: A case study. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38(6), 465–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-010-0436-7

McIntyre, L. L., Eckert, T. L., Fiese, B. H., DiGennaro Reed, F. D., & Wildenger, L. K. (2010). Family concerns surrounding kindergarten transition: A comparison of students in special and general education. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38(4), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-010-0416-y

Menzel, B. (2022). Kinderperspektiven auf institutionalisierte Elterngespräche in Kindertageseinrichtungen. Zeitschrift für Grundschulforschung, 15(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42278-021-00127-6

Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research: Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 9–18.

National PTA. (2021). National standards for family-school partnerships. National Office.

Plehn, M. (2012). Einschulung und Schulfähigkeit: Die Einschulungsempfehlung von ErzieherInnen - Rekonstruktion subjektiver Theorien über Schulfähigkeit. Klinkhardt.

Roth, S., & Faldet, A.-C. (2020). Being a mother of children with special needs during educational transitions: Positioning when “fighting against a superpower.” European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(4), 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1706247

Rouse, E., & O’Brien, D. (2017). Mutuality and reciprocity in parent-teacher relationships. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(2), 45–52.

Sands, M. M., & Meadan, H. (2022). A successful kindergarten transition for children with disabilities: Collaboration throughout the process. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(7), 1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01246-6

Smidt, W. (2008). Pädagogische Qualität in integrativen Kindergärten und Regelkindergärten. Empirische Pädagogik, 22(4), 537–551.

Then, D., & Pohlmann-Rother, S. (2023). Transition to formal schooling of children with disabilities: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 38, 100492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100492

Ward, U. (2018). How do early childhood practitioners define professionalism in their interactions with parents? European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(2), 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1442043

Warren, S. R., Martinez, R. S., & Sortino, L. A. (2016). Exploring the quality indicators of a successful full-inclusion preschool program. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 30(4), 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2016.1214651

World Health Organization. (2001). ICF: International classification of functioning, disability and health. WHO.

Zehbe, K. (2021). Dealing with transition in formal meetings of parents and pedagogic staff. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 29(4), 569–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.1941167

Zehbe, K., & Sonnenberg, F. (2021). Erziehungs- und Bildungspartnerschaft zwischen Kita und Eltern. Alice Salomon Hochschule Berlin; Fröbel e.V. Kita-Fachtexte.

Zeng, S., Pereira, B., Larson, A., Corr, C. P., O’Grady, C., & Stone-MacDonald, A. (2021). Preschool suspension and expulsion for young children with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 87(2), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402920949832

Zulauf, C. A., & Zinsser, K. M. (2019). Forestalling preschool expulsion: A mixed-method exploration of the potential protective role of teachers’ perceptions of parents. American Educational Research Journal, 59(6), 2189–2220. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831219838236

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Faculty of Human Sciences of the Julius-Maximilians-University Würzburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The authors adhered to the ethical guidelines for research with human subjects formulated in the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical guidelines of the German Society for Educational Sciences during project planning and conduction as well as the applicable national laws in terms of ethical and data protection issues. The authors also adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Faculty of Human Sciences of the University of Würzburg and planed/conducted their research in accordance with the ethical regulations applicable there. An additional ethical review of the research project by a research ethics committee did not take place as there were no vulnerable persons participating in the study and the research design did not include any questionable procedures (e.g., substance allocation).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

All participants provided informed consent for publication of excerpts of the data (interviews) in anonymized form.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Then, D., Pohlmann-Rother, S. Parent–Teacher Meetings in the Context of Inclusion: Preschool Teachers and Parents of Children with Disabilities in Counseling Situations. Early Childhood Educ J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01521-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01521-8