Abstract

Parents of infants and toddlers have expressed concerns that their children’s social-emotional development has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this intrinsic case study was to gather information about parents’ and caregivers’ perspectives of experiences in a remote early childhood music class that incorporated explicit social-emotional instruction based on state learning standards. This study is a follow up to a previous intrinsic case study concerning parents’ experiences in a remote early childhood music class. Families who chose to participate in synchronous online caregiver-child classes at a local community music school were invited to participate in interviews. Eight adults, representing seven enrolled families, chose to participate. Four themes arose from the interviews: (a) Pandemic and the Upheaval of Family Life, (b) The Experience of the Child in Remote Music Class, (c) The Role of the Parent in Remote Music Class, and (d) The Unpredictable World of Remote Music Class. We share implications for teaching and suggestions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 emerged in December 2019 and soon changed life for families around the world, including families with young children. In addition to the physical and medical impacts of COVID-19, children have experienced negative psychological effects (Brooks et al., 2020), and researchers have documented concerns about the socio-emotional development of children during this challenging time, including increased anxiety and social isolation (Egan et al., 2021). These concerns are particularly relevant for families with infants and toddlers because birth through age 5 is a critical period for socio-emotional development which lays the foundation for building life-long competencies, including self-management and positive relationship skills (CASEL, 2020; Denham et al., 2014).

Many activities for infants and toddlers pivoted to completely remote versions for the health and safety of children and their caregivers throughout portions of the pandemic (UNICEF, 2020). This change affected early childhood music classes, such as the classes offered at our local community music school in an urban Midwestern city. The transition to a remote format challenged early childhood music educators in areas including musicality, technology, and facilitating social interaction. This final area was salient both because social-emotional learning and social interaction are important to parents who enroll their children in early childhood music classes (Pitt & Hargreaves, 2016; Koops & Webber, 2021) and because of the pandemic’s negative effects on children’s social-emotional development (Wang et al., 2020). In a previous case study, parents who attended the music program at our local community music school expressed concerns about the pandemic’s effect on their children’s social emotional-development and requested the incorporation of explicit social-emotional learning activities in the remote music program (Koops & Webber, 2021). In this follow-up study we investigated parents’ perceptions on this newly incorporated curriculum in order to be responsive to their needs. Below, we review literature regarding (a) social-emotional development in early childhood, (b) socialization during the pandemic, (c) socialization in early childhood music classes, and (d) remote music learning during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Social-Emotional Development in Early Childhood

Social-emotional development is a broad term that encompasses diverse skills. Rose-Krasnor (1997) emphasized effective social interaction in her Social Competence Prism, a framework that includes skills such as empathy and social-problem solving skills as foundational components. She also stressed the context-dependent nature of social competence and acknowledged that it may be mediated by factors, such as gender, culture, and developmental stage. Denam et al. (2014) elaborated on this prism model in their model of social emotional learning which focused on “self-regulation, social awareness, responsible decision making, and relationship/social skills” (p. 428). Both of these models emphasized the multifaceted nature of social-emotional development.

A commonly accepted framework of social-emotional development comes from the Center for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, or CASEL (CASEL, 2020; Payton et al., 2000). This framework features five areas of competence which are “self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making” (CASEL, 2020, p. 2). In the United States, many states include social-emotional learning as part of their early learning standards for children in childcare and preschool centers. For example, Ohio’s early learning standards include guidelines for relationship skills such as an infant making eye contact with another child or a preschooler offering to share a toy (Ohio Department of Education, 2012).

People develop social emotional competencies through the process of social-emotional learning, or SEL. While development occurs throughout the lifespan, SEL is important in early childhood due to the rapid development of children from birth to age five (Ashdown & Bernard, 2012). Murano’s metanalysis of 48 studies suggested that SEL programs implemented in early childhood educational settings including childcare centers, preschools, and kindergartens have had positive effects on children’s social-emotional development, indicating that explicit instruction may be beneficial to the acquisition of social-emotional competencies in early childhood (Murano et al., 2020). Additionally, strong social-emotional skills in preschoolers are associated with positive outcomes later in life including improved academic performance (Durlak, 2011; Denham et al., 2014); and may even contribute to success in the workplace (Deming, 2017). Because of these benefits, caregivers and educators have an interest in nurturing young children’s social-emotional development.

Social-emotional education in early childhood may have lasting benefits to children’s ability to cope with adversity later in life. Sanders et al., (2020) explored the effectiveness of a preschool social-emotional learning curriculum in a longitudinal study involving 294 students. Parents reported adverse childhood events (ACEs) at the start of the study, and years later, the children reported their levels of social-emotional distress during the transitions to middle school and high school. The researchers found that access to the social-emotional learning curriculum in preschool lessened the negative impacts of early ACEs for participants in this study (Sanders et al., 2020). Social-emotional learning may have positive effects on resilience and the ability to cope with stressful situations.

Social-Emotional Learning and Early Childhood Music Classes

Social-emotional learning is a topic of increasing attention within early childhood music education. Parents commonly believe that music participation in early childhood has a positive effect on children’s development, including social-emotional benefits (Savage, 2015; Pitt & Hargreaves, 2017; Rodriguez, 2019; Abad & Barrett, 2020). For example, Pitt and Hargreaves (2016) found that many parents choose to enroll in early childhood music classes primarily for the purpose of social-emotional development, rather than for musical reasons. These researchers interviewed a total of 20 educators and parents who participated in parent–child group music making classes at Children’s Centres in England for children ages 0–3. They found that while the educators emphasized the importance of music for development and later academic learning, parents highlighted the social connection and emotional skills that they noticed in their children.

There is some longitudinal evidence that music participation in early childhood has positive effects on social-emotional skills. For example, Williams et al. (2015) examined the frequency of shared musical activities in the home among Australian children between the ages of two and three (n = 3031). Later, when the children were four and five years old, professionals assessed the children on several skills including attentional regulation, emotional regulation, and prosocial skills. The results showed an association between frequency of home music activities between ages two and three with prosocial skills and attentional regulation at ages four and five. However, these results pertain to music activities in the home and not in a group class setting.

Many scholars have investigated the role of early childhood music classes on children’s social-emotional development (Boucher et al., 2020; Ilari et al., 2019; Ritblatt et al., 2013); however, results have been mixed. Gaudette-Leblanc et al. (2021) explored these mixed results by conducting a meta-analysis to determine whether participation in early childhood music programs influenced social-emotional development indicators for children under age 6. Gaudette-Leblanc found that participation in music classes had a moderate positive effect on measures of social-emotional development but cautioned that more rigorous research is needed to be conclusive.

Socioemotional Effects of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Children

While the physical and medical impacts of COVID-19 continue to vary by community, children worldwide have been affected by lockdowns and social-distancing measures enacted to prevent the spread of the disease (Prime et al., 2020; UNICEF, 2020). Some children have experienced severe forms of trauma such as illness, financial instability, or the death of loved ones. Even children who are unaffected by these extreme events may experience negative psychological effects from lockdowns such as stress, fear, boredom, and even post-traumatic stress symptoms (Brooks et al., 2020).

Egan et al. (2021) noted that most of the research on the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic focused on older children and teens, so they decided to center children under 10 in their research. These researchers issued a survey to 506 parents in Ireland during May and June 2020 and found that most children missed the social connections they made in childcare and school. Parents also reported an increase in anxiety and tantrums. Additionally, the researchers found that younger children, ages 1–5, missed attending childcare and preschool more than older children missed attending school. Parents of younger children expressed concerns about toddlers’ development (Egan et al., 2021).

Challenges of Remote Early Childhood Music Classes

Prior to the lockdowns stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, there were few models for remote synchronous instruction for children aged five and under (Kim, 2020). Steed and Leech (2021) explored how American early childhood educators implemented remote learning activities for their students during spring 2020 and what challenges the educators encountered. These researchers found that early childhood educators reported delivering a variety of remote learning services including online lessons and story times, sharing learning activities with caregivers to complete at home, and email check-ins with families. The educators in this study reported several challenges of providing remote instruction including their own personal emotional toll of the pandemic and the lack of in-person interaction with students.

Remote early childhood music instruction has presented challenges similar to those faced by early childhood general educators. Koops and Webber (2021) found that parents expressed many of the same difficulties discussed above, such as the lack of in-person interaction between children and the teacher. Early childhood music educators have also developed concerns with class length (Koops & Webber, 2021), which was also a challenge for general educators (Szente, 2020).

Purpose and Research Questions

This study is a follow-up to a previous intrinsic case study of parents’ and caregivers’ observations of a remote early childhood caregiver-child music class (Koops & Webber, 2021). Specifically, participants expressed their concerns for children’s social-emotional development during the COVID-19 pandemic and asked for additional attention to this development within the context of the remote music class. When attending class in person, children had the opportunity to interact casually with one another before, during, and after class. Parents were concerned their children were missing these casual interactions. On a deeper level, parents expressed concern about lost social-emotional opportunities due to the wider isolation brought by the pandemic (Koops & Webber, 2021). Because the remote music class was administered through a community music school that also employed early childhood educators with specializations in social-emotional development, the director of the early childhood program proposed that those educators participate in developing a social-emotional curriculum to enrich the music class. This collaboration is described further in “Setting & Context for the Study,” below.

Given the concerns about social-emotional learning in early childhood during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the purpose of the current study, also an intrinsic case study, was to document parent perceptions of the continuing adaptation of a remote early childhood music class, including the addition of social-emotional curricular elements, in response to previous parent and caregiver input. We chose to focus on parent perceptions because these were central to both the experience of the current class and to their decisions about whether to continue in the program. Studying parent perceptions also aligns with previous research with early childhood music classes (Koops, 2011; Pitt & Hargreaves, 2016; Rodriguez, 2020; Savage, 2015). By understanding parent perceptions of social-emotional content of an online music class, educators and researchers may obtain guidance for such inclusion of material in future classes, whether online or in-person. Another reason we focused on parent perceptions rather than direct observation of the class was because direct observation would have been difficult over Zoom. Often, the child or adult participants moved on and off screen while engaged in activities. Their microphones were typically muted unless used for a specific sharing activity. We considered parent perceptions of the class shared in interviews to provide more detailed information than observation would have done.

The research questions for this intrinsic case study were:

-

1.

How did parents describe the experience of a remote early childhood music class?

-

2.

How did parents respond to the social-emotional learning videos and materials provided?

-

3.

What were parents’ perceptions of non-musical, teacher-led social-emotional development activities during the remote early childhood music class?

These research questions are situated within the reality of working, learning, and parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic. The class took place in September–November, 2020, and interviews occurred in January–February, 2021. In January–February 2021, vaccines were not yet available for the age group of the adult participants. Some schools in the area had reopened to school-age and preschool children, while other schools remained closed. There was an atmosphere of uncertainty about what would happen with the pandemic and when children would have the chance to return to typical activities. As researchers, we believed it was important to document the parent perceptions of the ongoing adaptations of the online music program, particularly surrounding social-emotional experience, since previous participants identified that as a concern (Koops & Webber, 2021).

Methodology

Setting & Context for the Study

The early childhood music class was part of the tuition-based early childhood music offerings at a community music school in an urban region in the Midwest. The program had paused during March–April of 2020, then offered a remote session during May–June 2020 (see Koops & Webber, 2021, for further details). Classes at the community music school were 45 min long when taught in person. Teachers sat on the floor with caregivers and children in a circle and led song and chant activities, movement, and instrumental exploration activities with xylophones, drums, and shakers. Many of the activities featured props such as beanbags, scarves, and a parachute. The classes followed the Music Play curriculum and guidelines described by Valerio, et al. (1998). As Valerio et al. advised, we asked parents to limit their talking and focus on singing and chanting during the class.

Based on comments from parents who participated in the initial remote session, we changed the class format to 35 min of music activities, followed by a goodbye song, and then ten minutes of activities geared towards developing social-emotional skills linked to the Ohio Early Learning standards (Ohio Department of Education, 2012). The remote music teachers dubbed this “Talk Time” as a way to indicate to parents and children that it was okay to talk. This stood in comparison to the music time, during which teachers asked parents not to talk, only to sing. Two early childhood intervention specialists who worked in the preschool that was part of the community music school created a 9-week curriculum based on the Ohio Early Learning standards. For each week, they filmed a video explaining a standard, such as “communicate emotions purposefully and intentionally, verbally and nonverbally” (citation removed for review process). The specialists demonstrated ways families could interact with their child to support development in the area addressed by the standard, performed a puppet show with two puppet characters to demonstrate specific social-emotional competencies, and offered several picture book selections that also related to the standard. The videos were between 4 min, 30 s to 10 min, 30 s and published as unlisted YouTube videos. The second author sent the video links to families on Monday each week using Class Tag, a classroom communication app. She sent a second video on Wednesday each week of herself discussing the week’s standard as it related to music and demonstrating a musical activity, either one that was used in class or something that was new to families. The participants were not required to watch the videos to participate in class. Remote music teachers watched the videos and incorporated the activities into “Talk Time,” so even if families did not watch the YouTube videos, they experienced some of the activities.

Design

We chose to conduct an intrinsic case study in order to document parent perceptions of the ongoing adaptation of an early childhood music class to a remote setting with an additional social-emotional learning curriculum. An intrinsic case study is an appropriate design when investigating an existing situation of interest, compared with an instrumental case study, in which the researcher seeks examples of the topic of interest (Creswell & Poth, 2018). We bounded the case to include parents and caregivers of children who participated in the Fall 2020 session of the remote early childhood music class. The primary data source was parent interviews. Secondary data included informal descriptions and feedback from the remote early childhood teachers on how the classes were going, including “Talk Time.” The context surrounding the case included knowledge of the music program as it existed prior to moving to the remote offering as well as the social-emotional curriculum development and roll-out. The music program was part of the offerings at a community music school with which we are both affiliated, and early childhood music courses were offered remotely to families during the 2020–2021 school year due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. We had previously conducted an intrinsic case study to document parents’ perceptions of the remote music class format (Koops & Webber, 2021). Three of the participants from the first study also participated in this study.

Participants

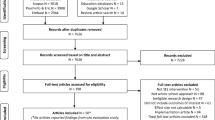

Several weeks after the close of the Fall 2020 session, we emailed parents from the 13 families who had participated in the session to invite participation in the case study (N = 13). Participants in this study were all parents (n = 8, representing 7 households) of children enrolled in online music classes for toddlers and preschoolers during the Fall 2020 session. Two of the participants were from the same household and participated in a joint interview. At the time of recruitment, the winter session had begun. Four families in the current study chose to continue participation in the spring session, while three families (four adult participants) had not re-enrolled. Participant pseudonyms, child ages, and interview dates are listed in Table 1.

The participants had various life circumstances regarding work and child care. During the course of the class, Allison and her husband balanced working full-time jobs from home and caring for Emily, all while Allison was pregnant with their second child. Hope and Bryan also worked full time jobs while their son Michael attended childcare. Ella worked a part-time job while her husband worked a full-time job from home. They balanced their jobs with caring for Joshua at home. Melissa was a stay-at-home parent to her son Grady while her husband worked outside the home. Sona had recently moved to the area to be closer to family, including her sister Siran who also participated in the study. Sona worked full-time from home as a lawyer while her husband worked outside of the home. She shares a nanny with her sister for childcare. Kelly and her husband both worked full-time jobs. Her husband was away from the home for work every other weekend, and Brayden attended childcare five days a week. Siran, who was newly pregnant with her second child, shared a nanny with her sister Sona in the afternoons. In the morning, Siran and her husband both worked full time from home while juggling caring for their daughter.

Data Collection

In inviting participants to the study, we specified that the interview would be no longer than 30 min. We chose this length because at this point in the pandemic (January–February 2021), our participants were experiencing high levels of stress and burn-out as well as Zoom fatigue. In addition, as parents of young children, they did not have much free time. We set up Zoom interviews with participants at mutually convenient times. We recorded the interviews using Zoom’s built-in recording feature. In the interviews we asked about the ups and downs of the Zoom music class experience, how it differed from in-person classes, and the parent and child favorite and least favorite parts of the class. We also inquired about their perceptions of the “Talk Time” portion of class and the social-emotional curricular videos. We invited reflection on the experience of parenting during the pandemic and what the most pressing issues of the experience were. Interviews lasted between 15 and 39 min, averaging 24 min. These interviews were shorter than those conducted in the previous study, possibly because the participants had already covered some of the basic information with the researchers. The two researchers conducted interviews separately, and Author 1 transcribed all of the interviews.

Analysis

Using the qualitative data coding software HyperResearch, we coded the interviews using structural and in vivo codes (Saldaña, 2015). We began by jointly coding three transcripts, then each coded two of the remaining transcripts individually. During this time, we kept a shared document with memos about new codes or questions that arose. We then checked one another’s coding for consistency. Following the collaborative coding process, we created a mind map of the codes, grouping them into themes and noting areas of relation and overlap. This analysis process resulted in the identification of four themes. We shared these themes, along with several bullet points illustrating each theme, with participants, inviting their feedback on whether the themes rang true for their experience. All participants responded positively.

In addition to the trustworthiness measure described above through seeking member checking from participants, we also submitted a portion of our coding analysis to a peer reviewer familiar with qualitative research and early childhood music for verification. The peer reviewer checked a selection of fifty percent of the coded material. She pointed out two sets of codes that were redundant, as well as highlighting one code that appeared less frequently than she would have expected. Otherwise, she affirmed that our coding was consistent and complete.

Researcher Roles

Author 1 is a preschool music teacher at one of the branches of the community music school’s preschool but does not teach parent–child early childhood music classes at the community music school. Author 2 has taught early childhood music classes there for fourteen years and taught the May–June 2020 session remotely but did not teach remotely during Fall 2020. She was the coordinator of the early childhood music programs Participants were familiar with Researcher 2’s name because she had been communicating with them about registration and the social-emotional curricular videos throughout the fall session. We believe this familiarity provided a positive relationship for the participant recruitment. Researcher 2 does not have any administrative role within the associated community music school or preschool, and thus did not pose any relational barrier to recruitment. The authors took turns interviewing participants. Author 1 did not know any participants personally, while Author 2 knew four of the seven participating families prior to this study. This familiarity may have encouraged the families to participate in the study. In order to guard against assumptions or over-familiarity, the authors worked together to analyze the data. Because of Researcher 2’s involvement in the program coordination, we have utilized the strategy of elapsed time to provide a fresh look at the data over a year later, during a time when we were not actively adapting a remote music offering.

Findings

We organized the codes into four themes: (a) Pandemic and the Upheaval of Family Life, (b) The Experience of the Child in Remote Music Class, (c) The Role of the Parent in Remote Music Class, and (d) The Unpredictable World of Remote Music Class. Of these themes, the first three were directly connected to the research questions, while the fourth was an emergent theme. We will discuss each theme in detail.

Pandemic and the Upheaval of Family Life

Many participants expressed that remote music class offered consistency from pre-pandemic life. The pandemic was challenging for Melissa, a stay-at-home parent, who had maintained a consistent routine for her son before the pandemic. Before the widespread lockdowns and closures, Melissa and her son Grady would go on outings to a specific location each day such as the library, the children’s museum, or music class. During the pandemic there were fewer activities available. This was especially challenging in the winter when outdoor activities were unavailable. Melissa explained the difficulties she faced and the appreciation she had for the remote music class:

It’s been a lot more difficult to kind of keep on a routine because…there just aren’t as many activities for him to be able to engage in…We were just really happy to be able to continue with one of Grady’s normal activities.

Like Melissa, Ella also felt that remote music helped her and her son Joshua maintain consistency. Ella described remote music class as “a piece of routine that still exists” when all other routines had been changed. For these families, music class represented a connection to pre-pandemic life which helped them structure their family life.

Many parents felt overwhelmed by the challenges of pandemic parenting. They suggested these challenges affected their ability to engage fully with the SEL materials that were provided as part of the remote music class. While Ella and Melissa accessed the social-emotional learning videos provided, other parents found that the pressures of pandemic parenting limited their ability to engage with anything extra. Siran did not watch the videos and described her experience: “It’s just one more thing to log into and have an account and that’s just more than I can deal with right now.” Hope and Bryan watched some videos but not all of them. Hope explained:

I thought they were good…it’s not that I had anything against them. It’s just that I work full time and [am] on a computer all day…and then Zoom calls with families, it just feels like a lot of screen time so…I thought they were interesting, but then a lot of the weeks I just…I just never got to it…[It] just felt like a lot that was hard to keep up with.

When asked whether she had watched the social-emotional learning videos, Sona responded with a sigh and said, “I wish I did. I’m kind of just like hanging on [by] a thread here.”

Some participants believed that exposure to remote music class helped their children gain familiarity with technology in order to communicate with extended family. Sona shared that her daughter Varduhi, age 22 months, independently calls her grandmother and teaches her songs from music class. Sona also credited music class with increasing her daughter’s familiarity with screens:

We had an interview at [a nearby private school] – a Zoom interview for her because I’m thinking about preschool – and she was so engaged in it because she’s so used to it. It was like an hour after music class on Saturday…So I think it’s working for these kids. At least my kid.

Hope and Bryan discussed how the necessity of screens to communicate with extended family members affected family routines and values. The couple used screens extensively to facilitate their son Michael’s communications with his grandparents. Hope explained that her father “has a genuine fear that Michael won’t have that connection with him because of this gap of the pandemic,” but she dismissed this concern because of the frequency of communication through video calls. Although Bryan recognized and valued the role of video calls in maintaining family ties, he also expressed concerns about balance:

And then also kind of balancing screen time, which I think is always a struggle. Because if you’re trying to maintain these connections primarily through phones and computers and…It’s hard to balance that because even – like I said, even with a two-year-old, he has this great draw to screens already, and it’s kind of scary.

Although the pandemic made screens a necessity for socialization which affected family norms and routines, some parents still have concerns about screens.

The Experience of the Child in Remote Music Class

Parents reported that children had varying levels of enjoyment of remote music class. For Brayden and Emily, the emotional connection with the teacher seemed to affect the class experience. Two-year-old Brayden’s mother Kelly was initially skeptical of the value of Zoom music class for toddlers. However, after seeing Brayden build a relationship with the teacher, Kelly changed her opinion: “I’ve actually thought on the whole it’s been really effective. He really enjoys the class…He talks about it…he literally talks about Miss Anna all week.” Brayden was able to build a relationship with his teacher although he had never met her in real life. In contrast to Brayden’s experience, Allison conveyed disappointment about the lack of emotional connection between her daughter Emily and the instructor. Allison described how Emily was excited to connect with the teacher, but she did not get the recognition she desired:

For the first few classes...I don’t think she heard her name at all. And so even just hearing her name and like having that validation, it just makes you...like makes you feel seen.

Because Emily did not feel seen, she gradually became disappointed with the class. Although Allison and Emily had a positive experience with remote music class in the past, Allison decided that they would not do remote class again and would instead wait for in-person classes to resume.

All participants who had taken in-person classes prior to the pandemic noted changes in engagement with the remote format. This included both those who responded more positively and somewhat negatively to the remote experience. For example, two-year-old Lucineh expressed excitement about music class and frequently sang the songs outside of class, but she often engaged in other non-musical activities during class such as reading books or playing with other toys. Siran explained that “she knows all the songs, and, you know, really likes to participate. But I think just the Zoom format is a little bit difficult with her age.” Siran described Lucineh as a tactile child who loves doing real-life activities such as washing dishes, so she attributed this lack of interest to the remote format rather than to the class activities themselves. Melissa encountered similar experiences with her son Grady:

And then the hardest part for me was just really trying to keep him engaged...I knew that he was listening to the songs, I know that he was still learning...[but] it could get a little frustrating because he would sometimes run out of the room, and so then I would have to get up and go get him. So then he would miss part

of the songs.

Melissa, Siran, and other parents noticed that their child was still engaged in music class activities, but their engagement was different and was subject to more distractions.

The format of the socialization portion of the remote music class was confusing for many children. Each class ended with 10 min of “Talk Time” that was intended to give the children a chance to practice specific social skills aligning with the social-emotional video curriculum. However, the teachers sang the goodbye song at the end of the music portion of the class which left some children confused about Talk Time. Kelly explained her son Brayden’s response to the formatting of the class:

They sang goodbye, and then he started trying to hang up and leave. And my husband was like “No it’s time for talk time!” and [Brayden] goes “No, she said goodbye!”

Brayden believed that class was done after the goodbye song and did not understand why people were not leaving class. Because Talk Time was at the end of class, many children began to show fatigue in addition to their confusion. All parents except Melissa and Allison said that their children were too tired and distracted to engage with talk time. In contrast, Allison’s daughter Emily experienced Talk Time as the most interactive part of the class. Allison explained:

I think Emily liked [Talk Time] because it was the time that she could show a toy and get validation for that, or listen to the other kids talk, or see them talk. So that was definitely the interactive part for sure.

For Emily, Talk Time was a chance to get the recognition that she felt was absent during the musical part of class, but for most children, it was not as engaging.

The Complex Roles of the Parent in Remote Music Class

Many parents found that their role in music class had changed due to the remote format of the class. Some parents found themselves acting as technology troubleshooters rather than participants in the class. Hope and Bryan had difficulty keeping the computer away from their son because he wanted to press all the buttons. Other parents found it difficult to manage muting and unmuting themselves as necessary during class.

A few of the comments participants made suggested that at times they were self-conscious about having their home life visible to other class members. For example, Kelly described the chaos that sometimes occurred during class with her son:

Sometimes we’ve got the dog with us, and then the dog’s barking out the window, right? And then I’m trying to mute and unmute...My husband never mutes ‘cause his view is [that] if we were in person, and [Brayden] was running all around there’s no mute button. But I always feel a little self-conscious. I don’t want everyone to have to hear me wrangling the dog and stuff.

Kelly felt the need to manage home situations such as the dog while also participating in class. This was different from an in-person class where the only focus is on the child and the activities.

Some parents noticed a change in their child’s class participation and had to come to terms with the fact that their children participated differently in remote classes versus in-person classes. Melissa, Hope, and Bryan all described feeling frustrated when their children would engage in other activities such as reading, playing, or running out of the room. However, they later realized that their children would sing the songs after class even though it seemed like they were not paying attention. Ella described how she came to terms with her own son’s perceived lack of interest in class by comparing it to an incident with a classmate:

There was a kid who was in one or two classes who was clearly... horrified. He put his head down, and was like, "No!!!" I felt a little bit bad. His mom was with him, and I think she was a little bit startled by this. But…Joshua doesn’t seem to be paying a lot of attention often, but he is [paying attention]. It seems all right, I mean, most of the other kids seem to be able to go away and come back.

Ella accepted that the children in the class would wander offscreen at times. She knew that even if the children appeared to be off task, they would return to class when ready. In contrast to Ella, Allison felt disheartened when her daughter Emily did not participate in class and was frustrated when other students were off-screen because "if a kid is off screen and their screen is just blank…you’re not getting that engagement."

Although participants noted that there were more distractions at home, some parents felt that it was easier for them to facilitate transfer of the activities. Melissa strove to help Grady gain independence by playing social-emotional learning games from the class videos. She saw the classes as a chance for her to get ideas of skills to work on with Grady at home. Bryan also embraced his role in facilitating transfer of activities to home. He described the importance of continuing to do activities outside of class by relating it to his experience as a music teacher:

It’s sort of like we talk about at school with rehearsals. Rehearsal shouldn’t be the only time that you play your instrument. You should be playing it when you go home, throughout the week...And these classes shouldn’t be the only time that the child does [musical and social-emotional] activities. It’s nice to have them weekly, but once you start learning the songs as the parents, then you can do them throughout the day and in the evening and things like that. So even if the class experience might not be ideal, doing it virtually versus in-person, you still are able to learn the material and interact with other people. So you can carry that throughout the week as a parent and have access to those resources.

Melissa and Bryan both saw virtual music class as a tool to help them in their role as parents.

The Unpredictable World of Remote Early Childhood Music Class

Participants’ overall impression of the class experience was that it was “unpredictable.” During this semester, parents observed their children changing moods from class to class. Hope said of her son Michael and his classmates:

[Toddlers] have their whims, but here were some weeks where there’d be a few songs in a row and he [was] just…not at all interested...And I don’t know the rhyme or reason to that. It varied week to week. Some weeks he seemed more interested, and other weeks, it’s just like, “Eh, I’m not really into this today.”

Hope found it hard to predict how class would go with Michael because of his rapidly changing interests. Sona had a similar experience with her daughter Varduhi. She shared that Varduhi’s attention during class seemed to shift rapidly from watching herself dance, to gazing at the teacher Anna, to calling out to her cousin and aunt who were also in the class:

It’s hard for me to tell [where her focus is] because sometimes I think she’s looking at her cousin and her aunt. You know what I mean? Sometimes she’s just like telling me – because she calls her aunt "Titi" – she’s like "Titi!" And I’m like "Right...let’s not make this about your cousin and aunt right now.”

Sona noticed that Varduhi displayed the same unpredictable attention span that Hope noticed in her son. In both cases, the children seemed to change interests rapidly and the parents could not understand why.

Some parents felt that the varying whims of their children made it more difficult for the teachers and expressed admiration at the instructor’s abilities to adapt. Bryan commended Anna for her ability to engage the children despite their rapidly changing activities:

I thought Anna did a really great job of engaging the kids. I mean, that’s got to be really hard when the kids are all over the place, trying to get them to pay attention and things like that. She’s just really good at being flexible with what the kids were doing. I thought she did really well with– with teaching the class.

Melissa also believed that Grady’s teacher Stacey did well adapting to the children’s whims; however, both Melissa and Bryan shared the opinion that adapting to the whims of the children seemed more difficult in remote class versus in-person classes.

Discussion

The first research question was about how parents described their personal experiences in a remote early childhood music class. Except for Sona and Varduhi who had never attended an in-person music class, all participants described the remote experience as different from their previous classes. While many parents had positive experiences with the remote class, they contextualized their positive comments within the pandemic. For example, they noted that they enjoyed the class given the circumstances, but still missed attending classes in-person. This aligns with previous research which has shown that parents prefer in-person music classes, but that they would rather have a remote class if the alternative were no class at all (Koops & Webber, 2021).

The participants’ responses indicated that they were predominantly focused on their children’s experiences in the class, not their own experiences as parents or musicians. Parents derived enjoyment from watching their children engage positively in music class. This is similar to findings from research concerning in-person music classes (Koops, 2011; Pitt & Hargreaves, 2016; Rodriguez, 2020). Some limitations of the remote format meant that the parents had to take on more roles including technology troubleshooter and dog-wrangler. This negatively affected the experience of the class for these families.

Another consequence of remote music class was the likelihood that children would engage in non-class related activities. When compared to their previous in-person experiences, parents appeared less comfortable letting their child roam around the room or not pay attention during remote class. This could be because there were more things to do at home. In class, there are a limited number of distractions, but at home the children had access to books and other toys. It may be that parents also felt vulnerable or judged. These findings are similar to previous findings in research regarding remote early childhood music classes (Koops & Webber, 2021) and can be understood through the concept of performative parenting (Friedman, 2013). Parents seek to present themselves in specific ways. Parents can often curate how they are seen by selectively sharing images of their home life on social media, but a synchronous virtual class may put their home life on display. This may result in stress and could explain why parents were anxious about their children engaging in other activities during music class.

The second research question centered on parents’ responses to the social-emotional learning videos and materials provided. The videos constituted a supplemental resource for all class members and participants were not required to watch them to participate in the study. One parent who viewed the videos did not find them helpful, while another watched the videos multiple times and enjoyed doing the activities with her son. However, the majority of participants did not view all of the videos and cited time as the limiting factor. They expressed a desire to view the videos and believed that they would be beneficial but felt overwhelmed by the pressures of pandemic parenting. This suggests that parents of young children may have experienced a similar emotional toll from the pandemic that has been reported by educators (Steed & Leech, 2021).

The final research question dealt with parents’ perceptions of Talk Time, the non-musical social-emotional development activities that occurred at the end of class. The participants’ opinions were divided on this portion of the class. Some parents enjoyed the activities but indicated that their children were too tired by the end of class to participate fully. Participants also noted that singing the goodbye song to mark the end of the musical part of class was confusing to the children because they thought the entire class was over. Emily was more engaged in Talk Time than she was during the musical part of the class, but this was not true for the other children. The diversity of responses highlights the importance of maintaining open communication between parents and educators regarding the goals and values of a caregiver-child music class (Pitt & Hargreaves, 2017).

Limitations

As is typical with a qualitative study, these results cannot be generalized to other early childhood music programs. The small number of participants and the specific context also limit generalizability. Additionally, as more organizations return to in-person formats, early childhood music programs will likely also resume in-person instruction. Most participants were familiar with Researcher 2 and knew of her involvement with the program. This may have hindered participants from sharing negative perspectives. On the opposite end of this familiarity spectrum, participants’ lack of familiarity with Researcher 1 may have caused them to limit information that they shared. Nevertheless, teachers and program directors may notice common themes with their own experiences and may choose to apply this knowledge to in-person teaching or to future remote classes for families who are unable to attend in-person classes for myriad reasons.

Implications for Teaching

Because of the diverse experiences of the participants, it seems that there is no “one size fits all” model for remote early childhood music classes. While it is possible that the remote format could be helpful for families who cannot attend in-person classes, teachers would need to tailor their programs to their specific communities. The socialization component likewise could be adapted to suit the needs of a given community. When designing a remote experience teachers should listen to families to understand their needs and preferences. It is also vital to provide materials in multiple formats and make them easily accessible at various times.

The focus on toddlers in this program yielded implications specifically for teaching toddlers in remote music classes. The most important implication is that the 35- or 45-min remote music class itself is only a part of the larger experience. During this time, the toddler may or may not participate in ways the teacher or parent hopes or expects. However, it is possible the toddler is still picking up ideas, sounds, and sequences that will later emerge during play. Teachers can help parents and caregivers understand this by using phrases such as “Be sure you as the adult continue to participate even if your child takes a break” or “Think of this time as a chance to gather ideas and strategies that you can use throughout the week.” A teacher could remind parents and caregivers that children respond in many ways during class, both in-person and during remote class, and that we welcome all of those interactions. As Bryan described, the class is just one part of the overall picture of musical participation.

Based on the feedback of participants about “Talk Time,” and based on collaborative discussions with the teachers, the teachers shifted “Talk Time” activities to be presented throughout the 45-min music class. They also moved the good-bye song to the very end of the class to reduce the confusion some children experienced. Even if a formal research study is not being carried out, keeping communication open and keeping the format flexible is important when adapting a program to an online offering.

While many programs may return to in-person format, remote early childhood music classes may still be valuable after the pandemic. Some families may be unable to attend in-person classes due to other health concerns or location. Due to concerns about the lasting effects of the pandemic on children’s social and emotional wellbeing (Dubey et al., 2020), teachers and program directors may consider adding more explicit SEL activities to both in-person and remote early childhood music classes. Educators who choose to do this may consider tailoring the SEL activities to specific concerns indicated by their communities and should work to accommodate families’ needs regarding communication. For example, because some families found the videos difficult to access, information about SEL activities could be shared in a different format such as a booklet or a flier.

Programs that continue to offer remote programming may choose to reassure parents that a range of participation is normal and expected. While this is an established practice for in-person classes (Valerio et al., 1998), it may need to be modified for a remote class. For example, instructors may take time to ensure that everyone is comfortable with the technology or to establish guidelines for muting and unmuting. It may be helpful to establish guidelines in collaboration with the participants of each class to make sure the diverse needs are met.

Suggestions for Future Research

As more programs return to an in-person format, it may be beneficial to investigate the role of SEL in early childhood music education. What strategies are most effective for blending SEL with music class? What are the social and emotional needs of toddlers after more than a year of a remote, potentially screen-heavy life during the COVID-19 pandemic? What role can music class play in the social and emotional development of young children?

Finally, it may be useful to research the possibility of continuing with a remote format for early childhood music classes; however, future remote programs may need to be newly designed rather than adapted from in-person models. Is this a format that could make these types of classes more accessible to diverse populations? Are there any situations besides a pandemic where families would choose remote classes over in-person offerings? In remote classes, what are the most effective communication strategies to avoid overwhelming families? Have the years of pandemic life and socializing with family and friends via technology changed how families view engaging in extracurricular classes online? These questions represent a rich opportunity to expand and improve early childhood music programs.

Change history

26 August 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01388-1

References

Abad, V., & Barrett, M. S. (2020). Laying the foundations for lifelong family music practices through music early learning programs. Psychology of Music. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735620937780

Ashdown, D. M., & Bernard, M. E. (2012). Can explicit instruction in social and emotional learning skills benefit the social-emotional development, well-being, and academic achievement of young children? Early Childhood Education Journal, 39, 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-011-0481-x

Boucher, H., Gaudette-Leblanc, A., Raymond, J., & Peters, V. (2020). Musical learning as a contributing factor in the development of socio-emotional competence in children aged 4 and 5: An exploratory study in a naturalistic context. Early Child Development and Care. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1862819

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

CASEL (2020). CASEL’s SEL framework: What are the core competencies and where are they promoted? Retrieved from https://casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CASEL-SEL-Framework-11.2020.pdf

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018) Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage

Deming, D. J. (2017). The growing importance of social skills in the labor market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(4), 1593–1640. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx022

Denham, S. A., Bassett, H. H., Zinsser, K., & Wyatt, T. M. (2014). How preschoolers’ social–emotional learning predicts their early school success: Developing theory, promoting, competency-based assessments. Infant and Child Development, 23(4), 426–454. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1840

Dubey, S., Biswas, P., Ghosh, R., Chatterjee, S., Dubey, M. J., Chatterjee, S., Lahiri, D., & Lavie, C. J. (2020). Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14(5), 779–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Egan, S. M., Pope, J., Moloney, M., Hoyne, C., & Beatty, C. (2021). Missing early education and care during the pandemic: The socio-emotional impact of the COVID-19 crisis on young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49, 925–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01193-2

Friedman, M. (2013). Mommyblogs and the changing face of motherhood. University of Toronto Press.

Gaudette-Leblanc, A., Boucher, H., Bédard-Bruyère, F., Pearson, J., Bolduc, J., & Tarabulsy, G. M. (2021). Participation in an early childhood music program and socioemotional development: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Music in Early Childhood, 16(2), 131–153.

Ilari, B., Helfter, S., & Huynh, T. (2019). Associations between musical participation and young children’s prosocial behaviors. Journal of Research in Music Education, 67(4), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429419878169

Kim, J. (2020). Learning and teaching online during COVID-19: Experiences of student teachers in an early childhood education practicum. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52, 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00272-6

Koops, L. H. (2011) Perceptions of current and desired involvement in early childhood music instruction. Visions of Research in Music Education, 17. http://www-usr.rider.edu/~vrme/v17n1/visions/article4

Koops, L. H., & Webber, S. C. (2021). ‘Something is better than nothing’: Early childhood caregiver-child music classes taught remotely in the time of COVID-19. International Journal of Music in Early Childhood, 15(2), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijmec_00018_1

Murano, D., Sawyer, J. E., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2020). A meta-analytic review of preschool social and emotional learning interventions. Review of Educational Research, 90(2), 227–263. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320914743

Ohio Department of Education (2012). Birth through kindergarten early learning and development standards. Retrieved from https://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Early-Learning/Early-Learning-Content-Standards/Birth-Through-Pre_K-Learning-and-Development-Stand

Payton, J. W., Wardlaw, D. M., Graczyk, P. A., Bloodworth, M. R., Tompsett, C. J., & Weissberg, R. P. (2000). Social and emotional learning: A framework for promoting mental health and reducing risk behaviors in children and youth. Journal of School Health, 70(5), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06468.x

Pitt, J., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2016). Attitudes toward and perceptions of the rationale for parent-child group music making with young children. Music Education Research, 19(3), 292–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1145644

Pitt, J., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2017). Exploring the rationale for group music activities for parents and young children: Parents’ and practitioners’ perspectives. Research Studies in Music Education, 39, 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X17706735

Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660

Ritblatt, S., Longstreth, S., Hokoda, A., Cannon, B.-N., & Weston, J. (2013). Can music enhance school-readiness socioemotional skills? Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 27(3), 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2013.796333

Rodriguez, A. M. (2019). Parents’ perceptions of early childhood music participation. International Journal of Community Music, 12(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.12.1.95_1

Rodriguez, A. M. (2020) “I am doing this just for you!”: Musical parenting and parents’ experiences in an early childhood music class (Publication No. 28256737) [Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University]. ProQuest

Rose-Krasnor, L. (1997). The nature of social competence: A theoretical review. Social Development, 6(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.1997.tb00097.x

Saldaña, J. M. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Sanders, M. T., Welsh, J. A., Bierman, K. L., & Heinrichs, B. S. (2020). Promoting resilience: A preschool intervention enhances the adolescent adjustment of children exposed to early adversity. School Psychology, 35(5), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000406

Savage, S. (2015). Understanding mothers’ perspectives on early childhood music programmes. Australian Journal of Music Education, 23(2), 127–139.

Steed, E. A., & Leech, N. (2021). Shifting to remote learning during COVID-19: Differences for early childhood and early childhood special education teachers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49, 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01218-w

Szente, J. (2020) Live virtual sessions with toddlers and preschoolers amid COVID-19: Implications for early childhood teacher education. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 373–380. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216174/

UNICEF (2020). Early childhood development and Covid-19. Retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/topic/early0-childhood-development/covid-19/

Valerio, W. H., Reynolds, A. M., Bolton, B. M., Taggart, C. C., & Gordon, E. (1998). Music play: The early childhood music curriculum guide for parents, teachers, and caregivers. USA: GIA Publications.

Wang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., & Jiang, F. (2020). Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet, 395(10228), 945–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30547-x

Williams, K. E., Barrett, M. S., Welch, G. F., Abad, V., & Broughton, M. (2015). Associations between early shared music activities in the home and later outcomes: Findings from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.01.004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: the citation Gaudette-Leblanc, 2021 has been corrected as Gaudette-Leblanc et al., 2021 and its corresponding reference also updated.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Webber, S.C., Koops, L.H. “A Piece of Normal Life When Everything Else is Changed” Remote Early Childhood Music Classes and Toddler Socialization. Early Childhood Educ J 51, 1253–1264 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01371-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01371-w