Abstract

During COVID-19, many schools in the United States restrict parent visits and parent-teacher face-to-face meetings. Consequently, teachers and parents rely on digital technologies to communicate and build partnerships. Yet, little is known about their perceived experiences with digital communication. To contribute knowledge to this area, this study investigated the perceptions of the classroom teacher and parents of preschool children concerning their experiences of communicating with each other via digital technologies during COVID-19. The participants consisted of one teacher and three mothers of 3-year-olds in the same classroom of a private childcare center serving preschool children from mostly middle-class backgrounds in a northeastern state of the United States. The teacher and parents were interviewed individually and virtually via Zoom for 30–60 min (M = 45 min). A thematic analysis uncovered four salient themes: (1) modes of digital communication between the teacher and parents, (2) the nature of digital communication, (3) limitations of digital communication, and (4) digital communication via ClassDojo. The ClassDojo theme further revealed three subthemes: (1) ClassDojo for promoting proactive parent involvement, (2) ClassDojo for building teacher-parent partnerships, and (3) the use of limited functions of ClassDojo. The data were triangulated by analyzing teacher-parent communication artifacts on ClassDojo, which confirmed the findings related to the use of this digital platform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent decades, the proliferation of digital technologies has reinforced a digital model of operation in many sectors. In the education realm, it has encouraged the “digitalization of educational practices” (Colombo, 2016). This phenomenon may be described as the innovative application and integration of digital technologies in the dynamic process of teaching and student learning. Teacher-parent communication is an integral, yet less-examined, facet of the digitalization of educational practices (Erdreich, 2021). Given that many teachers and parents have begun to experiment with leveraging innovative digital technologies (e.g., email, e-newsletters, text, apps) to communicate with each other (e.g., Abubakari 2020; Bordalba & Bochaca, 2019; Patrikakou, 2016; Wasserman & Zwebner, 2017), it is imperative that we develop a better understanding of how digital communication may facilitate the fostering of teacher-parent partnerships, insights that can help guide practice. Strong partnerships between teachers and parents are highly valued because they play a key role in the education of the children they “share” (Epstein, 1995, 2016; Epstein et al., 2018). However, the nature of these partnerships is variable, affected by contextual demands and communication practices.

The COVID-19 pandemic has induced unwelcome interruptions on humanity in general and the educational process in particular. In the United States, even among schools that have reopened for in-person instruction during COVID-19, many still bar in-person parent visits and/or parent-teacher face-to-face meetings. Thus, while establishing teacher-parent partnerships continues to be critical, it has become more complicated in the time of COVID-19 when communication is largely restricted to digital forms. In turn, digital communication has seemingly reshaped the partnership discourse between teachers and parents. Yet, we know little about the ways in which both teachers and parents build and sustain their partnerships through digital communication during COVID-19. As an effort toward this direction, we investigated the perceived experiences of a preschool teacher and parents in leveraging digital technologies for communication and thereby establishing teacher-parent partnerships.

The Importance of Teacher-Parent Partnerships

Teacher-parent partnerships may be defined as the coordination and collaboration between parents and teachers in mutual and active participation in the education of the children they “share” (Epstein, 1995, 2016; Epstein et al., 2018). It is widely acknowledged that children’s educational experiences are optimized when teachers and parents establish collaborative partnerships. This recognition is rooted in the theoretical perspective (e.g., Bronfenbrenner 1979, Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) and empirical evidence (e.g., Barnett et al., 2020; Galindo & Sheldon, 2012) highlighting the positive effects of strong teacher-parent partnerships on children’s development, learning, and academic success. The resultant positive outcomes for children include enhanced school readiness for kindergarten (Barnett et al., 2020) and better academic performance (Galindo & Sheldon, 2012). Particularly, in this digital age, parents and teachers can leverage digital media to communicate with each other to enhance student learning and success. For example, in their systematic review of studies on the role of technology-mediated parent engagement in the educational outcomes of students (preschool to high school), See et al., (2020) found some evidence supporting bidirectional, personalized, and constructive teacher-parent communications via digital means (e.g., texts, emails) as helping to optimize student outcomes (e.g., better academic engagement, increased school attendance).

Just like any other relationship, building strong partnerships between teachers and parents requires positive communication. However, unlike other relationships, the professional partnerships between teachers and parents are unique because they are bound by the imperative of achieving the common goal of facilitating successful educational experiences for children who are at the center of this endeavor (Chen, 2016). Given the importance of both parents and teachers in children’s education, establishing strong teacher-parent partnerships has been implemented as an integral aspect of the educational process in U.S. schools (Epstein, 1995, 2016; Epstein et al., 2018) and early childhood settings (Chen, 2016; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). Notably, in the early childhood field in the United States, the idea and practice of fostering positive teacher-parent partnerships have been endorsed fervently by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) concerned with the quality of care and education for young children (ages birth to 8 years). As evidence of this, forming positive partnerships between teachers and families is a critical feature of the NAEYC’s (2019) accreditation standards. Furthermore, NAEYC (2020) advocates “engaging in reciprocal partnerships with families and fostering community connections” as a developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood education (p. 14).

During COVID-19, positive partnerships between teachers and parents are more critical than ever in helping young children navigate learning under unique educational circumstances, while they themselves are also learning new ways to communicate with each other. However, the extant literature on early childhood educators’ experiences during COVID-19, thus far, has focused primarily on their pedagogical adaptations and mental health (e.g., Bassok et al., 2020; Chen, 2022; Nagasawa & Tarrant, 2020; Randall et al., 2021), leaving the area of digital communication between teachers and parents in building partnerships open for investigation.

The Power of Communication in Teacher-Parent Partnerships

Effective teacher-parent communication has been recognized as a building block of positive teacher-parent partnerships (Chen, 2016; Epstein, 1995, 2016; Epstein et al., 2018). This perspective is also supported by research evidence (e.g., Abubakari 2020; Barnett et al., 2020; Galindo & Sheldon, 2012; Kraft & Rogers, 2015). However, for teacher-parent communication to be successful, it needs to be conducted in bidirectional, personalized, and positive manners (e.g., Bordalba & Bochaca 2019; Ho et al., 2013; See et al., 2020). For instance, the teacher may communicate critical information about the child, child development, and teaching strategies to help guide a parent’s approach to working with the child at home (Barnett et al., 2020). Likewise, a parent may share critical insights about the child’s developmental characteristics that the teacher can consider when implementing pedagogical strategies to better work with the child in the classroom (Chen, 2016). As digital technologies and media are becoming increasingly prevalent and readily available, teachers and parents can leverage these digital tools and platforms to communicate with each other about a variety of matters related to the child’s education (e.g., Kuusimäki et al., 2019a; Kuusimäki et al., 2019b).

Whether through digital or non-digital media, effective communication is at the very heart of building and sustaining strong teacher-parent partnerships. When teachers make intentional efforts to engage parents in their children’s education by fostering responsive communication, the parents are likely to respond in kind by being more motivated to engage in their children’s education as well as feeling more connected to the teachers and the classroom learning (Chen, 2016; Green et al., 2007; Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2005; Kelty & Wakabayashi, 2020). The parents may also feel empowered with a “voice” to participate in their children’s education through various opportunities, a process that is generally known as parent/family involvement or parent/family engagement (Chen, 2016; Epstein, 1995, 2016; Epstein et al., 2018).

While there appears to be no consensus on the definitions of parent involvement, scholars (e.g., Epstein 1995; 2016; Epstein et al., 2018; Olmstead, 2013) generally define this construct as multifaceted, with each facet encompassing certain distinct activities. For instance, Epstein (1995) defined parental involvement as entailing six types: (1) “parenting,” (2) “communicating,” (3) “volunteering,” (4) “learning at home,” (5) “decision making,” and (6) “collaborating with the community.” Inherently, a key manifestation of parent/family involvement practices entails effective communication between teachers and parents. Proffering a different framework, Olmstead (2013) distinguished parent involvement into only two types: (1) “reactive involvement” which is school-based, referring to parents’ active physical involvement in school activities (e.g., attending meetings, volunteering), and (2) “proactive involvement” which is primarily home-based, entailing parents’ active support of their children’s learning at home (e.g., helping a child with homework, keeping track of a child’s learning progress). During COVID-19 when face-to-face interaction is restricted, proactive parent involvement may be the most feasible practice because it does not require the parents to be physically present at the child’s school. Given this circumstance, teachers may build positive partnerships with parents by encouraging them to engage in proactive involvement. While strong partnerships between teachers and parents are highly valued in early childhood education in the United States (Chen, 2016), its actual practice is more complicated due to the modes, and their associated nature, and purposes of communication.

Traditional Modes of Teacher-Parent Communication

As summarized in Table 1, there are myriad traditional modalities through which teachers and parents communicate with each other. Traditionally, teacher-parent communication occurs primarily in routinized, bidirectional, and face-to-face interactions and unidirectional print materials (Barnett et al., 2020; Chen, 2016; Decker & Decker, 2003; Epstein, 1995; Rogers & Wright, 2008). Face-to-face is considered the most popular traditional method of communication between teachers and parents. It is conducted synchronously in real time, affording both parties the opportunity to “read” each other’s body language (e.g., facial expressions) and audio cues (e.g., tones) to potentially avert misinterpretation of messages and allow opportunities for clarification and mutual understanding (Chen, 2016; Decker & Decker, 2003; Wasserman & Zwebner, 2017). Given this advantage, there is no digital substitute for face-to-face communication. Despite its apparent popularity and advantages, the traditional face-to-face form of communication also carries drawbacks. First, it requires both the teacher and family to be physically present at the child’s school, and involves planning, scheduling, and making arrangements (Chen, 2016), all of which can engender inconvenience. Second, face-to-face meetings require time that both busy working parents and teachers may not have (Rogers & Wright, 2008). The inconvenience and time burden incurred by traditional face-to-face communication suggests the need for innovative alternatives.

Digital Modes of Teacher-Parent Communication

In this digital age, possibilities for communication abound. The expansive array of new media and information technologies has afforded an increased selection of alternative and new communication channels between teachers and parents befitting their needs and comfort levels, thereby broadening their partnership horizons. For example, teachers have increasingly leveraged technology to enhance communication with parents (e.g., Bordalba & Bochaca 2019; Olmstead, 2013). In a study based on surveys with teachers and parents and focus group interviews with parents of elementary school students in the United States, Olmstead (2013) found that both parents and teachers highlighted technology as facilitating their communication efficiently and effectively, a process which, in turn, encouraged parent involvement and benefited children’s academic performance. Specifically, Olmstead found that all seven participating teachers believed that “it was important or very important” that they established communication channels with parents using technology, and the majority of parents (81 out of 89) also shared this belief.

Table 2 summarizes some common digital media tools (e.g., emails, online platforms) utilized by teachers and parents to communicate with each other. As digital devices (e.g., computers, mobile phones, iPads) connected to the Internet become pervasive, educators and parents have also started using a variety of digital communication tools and platforms including emails (e.g., Bordalba & Bochaca 2019; Rogers & Wright, 2008; Thompson, 2008; Thompson, 2009), social networks (e.g., Facebook, Karapanos et al., 2016), and mobile apps, such as WhatsApp (e.g., Aviva & Simon 2021; Karapanos et al., 2016; Wasserman & Zwebner, 2017) and ClassDojo (e.g., Bahceci 2019). Among these digital media, email remains the most popular among teachers and parents of children from preschool to high school (Laho, 2019; Olmstead, 2013; Rogers & Wright, 2008; Thompson et al., 2015). In their study of 1,349 parents concerning their communication modes with teachers of students in first through 12th grades, Thompson et al., (2015) found that the majority of the parents preferred email communication because it was convenient, asynchronous in nature, efficient, and easily accessible via smartphones.

The digital platforms have offered both teachers and parents a variety of choices for communication. One noticeable trend is that teachers and parents appear to have leveraged mobile devices to progressively incorporate the use of apps in their communication. In particular, ClassDojo, a free mobile education-oriented app, has become one of the most popular digital communication tools used by educators. According to ClassDojo’s website (https://www.classdojo.com/about/), “98% of all K-8 schools in the U.S. and 180 countries” are active users and “1 in 6 U.S. families with a child under 14 use ClassDojo every day” (n.d., n.p.). Some of ClassDojo’s communication features include a feed for sharing materials (e.g., relevant photos and videos from the school day and from home, instructional materials) and exchanging messages between teachers and families which can be translated into many languages. ClassDojo has been found to help increase parental involvement (Bahceci, 2019).

The prevalent use of digital technologies for communication between teachers and parents may be attributed to the immediate and convenient effects, as such communication can occur anywhere at any time with any mobile devices. It is conceivable that teachers and parents are likely to connect with each other via methods that are convenient and efficient. Thus, it is not surprising that digital technologies, especially smartphones and other mobile devices, have become the obvious choice for communication (Ho et al., 2013; Rideout, 2017; Thompson et al., 2015). Particularly, smartphones have become the most popular choice because they are made increasingly affordable and available. Nationwide in the United States, irrespective of socioeconomic status, among families with children age 8 and younger, 95% of them in 2017 compared to only 63% of them in 2013 had a smartphone (Rideout, 2017). As digital technologies and media are becoming increasingly available to families, they serve as enablers of more efficient and effective parent-teacher communication. However, they can also serve as constrainers due to various digital barriers confronting parents and teachers, including limited digital competence, negative attitudes toward technology and the use of digital media for parent-teacher communication, and different learning curves (e.g., Bordalba & Bochaca 2019; Palts & Kalmus, 2015; Rogers & Wright, 2008). As teachers and parents increasingly engage in digital communication, especially during COVID-19, it makes it all the more important that we investigate ways in which digital technologies and media may enable and/or constrain teacher-parent communication.

Leveraging Digital Communication During COVID-19

During the COVID-19 era, face-to-face communication has been restricted (if not eliminated all together) in U.S. schools and early childhood settings. This phenomenon has led teachers and parents to rely (mostly, if not solely) on alternative media of communication to develop and maintain their partnerships in the children’s education (Laxton et al., 2021). Digital technologies have, thus, been catapulted even more into the forefront of the communication discourse and served as creative means for teachers and parents to form partnerships. Yet, there is a dearth of knowledge concerning technology-mediated teacher-parent interactions during COVID-19. To contribute insights to this area, this study investigated the perceived experiences of the classroom teacher and parents of preschool children in establishing their partnerships via digital communication.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory as the theoretical Framework

This study was informed by Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory of human development. According to this theory, child development occurs and is affected by an intricate web of mutually influencing contexts, spanning from the innermost microsystems (e.g., family in the home, teachers and peers in the school), the mesosystems (the link between two microsystems), to the outermost macrosystems (e.g., culture, society). Accordingly, the home and the early childhood program constitute two essential microsystems that collectively exert the most immediate and direct influences on children’s development, as reflected in the proximal processes by which these children engage in direct, reciprocal, and sustained interactions with their parents and teachers. In this connection, parent-teacher partnerships constitute an essential mesosystem (the interaction between the two microsystems, namely the parents and teachers) that naturally impacts child development and learning. When teachers and parents are both actively involved in building professional partnerships, a process through which teachers are likely to feel connected to the children and their parents, and likewise, the parents are likely to feel connected to the teacher and classroom learning (Chen, 2016). Thus, examining the mesosystem linking teachers and parents is critical to better understanding the nature of teacher-parent partnerships.

The Goal of This Study

This study investigated the perceptions of one preschool teacher and three parents in leveraging digital technologies and media for communication as a central aspect of building teacher-parent partnerships during COVID-19. To this end, we (the two researchers) endeavored to address this research question: How do the teacher and parents of preschool children perceive their experiences of engaging in digital communication with each other during COVID-19?

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the researchers’ university and research ethical practices were followed. A signed informed consent letter was obtained from each participant.

Research Method

Participants

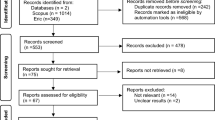

To address our research question, we recruited a convenience sample of participants from a private childcare center where the second researcher was a teacher. Located in a northeastern state of the United States, this childcare center had just reopened for a two-month summer program (from July-August 2021) conducted in-person for the very first time since closing in March 2020 due to COVID-19. The summer program consisted of two classes, with each enrolling 15 children from mostly middle-class backgrounds. Each class was taught by two co-teachers. Because the second researcher was a co-teacher in one of the two classes, to avert a conflict of interest, we only recruited participants from the class that was not taught by her. Although both co-teachers and all parents of children (ages 2.5–5 years) in this one class were invited to participate in this study, the recruitment of participants proved challenging during COVID-19. One co-teacher and some parents cited emotional strains and time limitations imposed by COVID-19 as reasons for declining participation. Consequently, only one co-teacher and three parents consented to participate. Given its small sample size, we perceived this study as an exploratory effort to begin understanding digital communication between teachers and parents during COVID-19.

This study consisted of one teacher (Petra) and three mothersFootnote 1 (Alba, Danielle, and Nancy). These names were pseudonyms that we used to protect the confidentiality of the participants. Petra (age 45) was a veteran teacher with 20 years of teaching experience, 10 of which were in early childhood grades (preschool-3rd). She held a B.A. degree in elementary education (kindergaraten - 8th grade). Among the three mothers (each had a 3-year-old child in Petra’s preschool classroom), Alba was a 31-year-old Caucasian, Danielle was a 37-year-old Jamaican American, and Nancy was a 38-year-old Latina.

Method of Data Collection

To achieve the goal of this study, we first developed an interview protocol by following Patton’s (2015) “interview guide approach.” The interview protocol consisted of the same eight core open-ended questions asked of the teacher and the three parents, respectively. The questions revolved around their perceived experiences of leveraging digital technology to communicate with each other (see Appendix A for a list of main interview questions). The participants were interviewed individually and virtually for 30–60 min (M = 45 min) by the second researcher via the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act version of Zoom to provide added protection of privacy of the information shared. The interviews were all conducted in a semi-structured, flexible manner to allow the interviewer to ask each interviewee pertinent clarification, elaboration, and follow-up questions (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). The interviews were conducted after the summer program had concluded, when the teacher and parents might have had time to reflect on their communication experiences. These interviews were video- and audio-recorded by Zoom, and the audio recordings were subsequently transcribed with the assistance of a transcription software. To enhance the flow of ideas, filler words, such as “uh,” “you know,” “um,” were deleted from the final interview transcripts. In presenting the quotes from the interviews, we added some words and phrases in brackets to help either contextualize or clarify a quoted statement.

In addition to employing interviews as the main source of data, we conducted data triangulation by analyzing digital communication artifacts between the teacher and parents on ClassDojo.

Method of Data Analysis

We applied Corbin and Strauss’s (2015) open coding techniques, including applying codes to the data and then grouping these codes into categories from which to develop emerging themes. Additionally, we examined the data using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), involving identifying patterns in the data or emerging themes. In particular, we focused on identifying themes only at the semantic level. As distinguished by Braun and Clarke, semantic themes are derived from describing and interpreting within only what the participants explicitly stated.

As the two researchers of this investigation, we each independently analyzed the data, including coding them for themes and then comparing these themes within and across all participants, particularly noting their similarities and differences. For instance, when analyzing the data detailed in both the teacher and parent transcripts, we identified three codes (email, texting, and ClassDojo) as referring to the shared theme of modes of digital communication. We also engaged in an iterative process of checking and rechecking the data to resolve any disagreements in coding and interpretation and reach consensus. The final themes and subthemes identified reflect these efforts and represent our collective findings.

Results

The analyses of the interview data and digital artifacts on ClassDojo revealed four salient themes: (1) modes of digital communication between the teacher and parents, (2) the nature of their digital communication, (3) limitations of digital communication between the teacher and parents, and (4) engaging in digital communication using ClassDojo. Within the ClassDojo theme, three subthemes were also identified: (1) ClassDojo as a valuable digital platform for promoting proactive parent involvement, (2) ClassDojo as a valuable digital platform for building teacher-parent partnerships, and (3) the lack of use of certain functions of ClassDojo.

Modes of Digital Communication Between the Teacher and Parents

When asked about their modes of communication via technology, both the teacher and parents all agreed that email, text via a smartphone, and ClassDojo, were the main ones. For instance, Petra (the preschool teacher) described:

[In the beginning,] we were mostly talking to our parents through email like sending a message and keeping in touch. This summer, I mostly did the ClassDojo and sometimes we also did text messaging. We also did FaceTime on the phone as well.

Similarly, the parents also communicated with Petra via email. For instance, Nancy used emailing as a digital means to learn about her child’s school day:

I have just sent an email to both [teachers to find out] when we are as parents going to get a sense of what [the children’s] days are like. What is the schedule for the day? Are we going to get a sense of like themes?

Texting served as a common form of digital media that both the teacher and parents used for communication with each other. In addition to emailing, Danielle communicated with the teacher via text, such as responding immediately to the teacher’s question concerning her child’s allergies:

Sometimes [the teacher] sends a text message to my phone since my child has allergies. So just get the OK whether or not she can do something so that I [approve].

Nancy had also used texting to communicate digitally with the teachers:

In the beginning [of going back to school in-person], I texted [the teachers] about [a personal issue about my child]…but other than that, I haven’t really reached out to anyone through the phone.

However, when ClassDojo was set up, Nancy relied on ClassDojo more than texting to attain information posted by the teachers:

As far as communicating [with the teachers]… In the beginning when they started in July, there was a lot more back and forth of… texting personal phone with [the teachers] and then like once the ClassDojo was up and running and pictures were being posted, then there was a lot more [use of ClassDojo.] I was able to see what the day’s activities were or who [my son] was playing with and that was cool.

The Nature of Digital Communication Between the Teacher and Parents

While both the teacher and parents communicated via email, text, and ClassDojo, the nature and purposes of their digital communication varied. For example, Petra described how she communicated with the parents about the child’s learning by emailing them photos and videos:

[I communicate with them] maybe more as needed, but I am [emailing] photos to them of daily activities that we are doing in class… So, I actually do videotape [what the children are working on] and then I [email] it to that parent individually.

Whether it was through email or ClassDojo, Danielle thought mass messages from the teacher acted more like a one-way communication:

I think I don’t reach out more because it seems like there are general messages going out when there’s something that the parents need to know. …It looks like a thread that the teacher is sending us messages because I can go through all of her messages, but I haven’t seen any responses from parents, so it doesn’t look like it’s eliciting information. It just looks like she’s keeping us up to date.

In addition to communicating with the teacher via email, Nancy shared that the virtual Open House was another source of information and an opportunity for parents to ask questions:

Probably in the first week or two that I emailed [the teachers] and then now, I have just been waiting for this virtual Open House and parents like to kind of get certain things answered.

Limitations of Digital Communication Between the Teacher and Parents

Despite the instrumentality of digital communication, Petra found that when discussing serious issues, she still preferred face-to-face meetings as she described:

I feel like with [serious issues], I would like to speak to the parent face-to-face. I just think it’s more personable so I feel that most of the time when I feel that we have an issue, I wouldn’t probably send it on my ClassDojo. I would probably meet the parent after school or before school one-on-one and say, “do you think you could come in?” So we can have a meeting and discuss what’s going on with their child. That’s mostly what I would do on that issue.

While citing convenience as an advantage of having remote parent-teacher conferences, Alba felt that the COVID-19-imposed restrictions of classroom visits deprived parents the opportunity to “experience the world with [the children]” (e.g., being in the classroom, seeing the children’s learning products):

I feel like it’s convenient to have remote parent-teacher conferences, but there’s just something missing from that parent-teacher relationship with them being remote… I just think of the experience in the classroom, the parents being able to step into their child’s world…Since you can’t volunteer, you are not in there so you don’t get to experience that world with them.

Alba also lamented the difficulty of building a professional relationship with the teacher virtually via digital technologies due to the lack of “personable” or “personal” face-to-face interactions to see each other’s physical and emotional reactions:

I really think that it’s hard to build a relationship with the teacher virtually because you only have ClassDojo, or email, and both are not personable or personal. So it’s just kind of hard… I don’t think it’s personal because there’s no tone in a text, you could say “thank you…” It’s just not the same. So, when you say something in person, you can emphasize something. You can use an exclamation point…but you can’t see the joy on somebody’s face…It comes off differently in a bland text message or ClassDojo message than it does in person. Unfortunately, I feel like that’s where the digital world is lacking.

Sharing Alba’s perspective, Danielle also found face-to-face interactions to be critical for building teacher-parent relationships:

There’s no face-to-face contact and what I know [according to work experiences] that I need to see the patient. I need to have that visual of the patient to see how they are doing. So have those non-verbal cues and they are highly important with building that rapport… So, for myself, it’s highly important to be able to have that face-to-face [interaction].

Sharing the same reasons as Alba and Danielle, Nancy also desired to have in-person one-on-one interactions with the teacher about her son rather than through digital communication:

I have had communication with [the teacher] through text…But then I do find myself wanting to speak with the teachers… I’m more curious to speak with the teachers one-on-one to know…What’s [my son] doing? What is he doing instead? What does he like to do? That’s not something that I feel like I can really have a whole conversation through technology.

Furthermore, Just like Alba and Danielle, Nancy described several advantages of in-person interaction including “getting an immediate response,” seeing the teacher’s reaction, and responding accordingly:

I guess it’s just the difference of getting an immediate response like getting a sense of body language and then depending on the response, following up with something and seeing the [other person’s] reaction… I feel like it’s hard to have a conversation through text…I can’t imagine texting [and] not being able to see what the reaction is like from the teacher...There’s definitely a lot that would be missed through text. I want to feel like I’m connecting with [the teacher] as the person that’s helping my child.

Engaging in Digital Communication Via ClassDojo

Given that the teacher implemented ClassDojo for the first time, it was new to her and it was equally novel to the parents. Thus, at the time of this research, both the teacher and parents had only begun to learn about ClassDojo and experiment with establishing communication using this digital platform. The findings revealed three subthemes related to their engagement in digital communication using ClassDojo: (1) promoting parent involvement, (2) building teacher-parent partnerships, and (3) lacking full use of this digital platform.

ClassDojo as a Valuable Digital Platform for Promoting Proactive Parent Involvement

Given that both the teacher and parents had not received any formal training in using ClassDojo as a digital platform for communication, they were learning to use it merely on their own. Thus, during the summer program, the teacher and parents only used ClassDojo for basic communication. For instance, Petra explained how she used ClassDojo to mainly share videos with the parents about their children’s learning in the classroom as a means to spark conversation between the parents and the child at home:

I videotaped while [a child] was [painting.] So, the parents got the videotape while it was happening and the next day, they got the real painting. So, the mom was like “Oh my God, I was so excited to see you painting this yesterday, and I love it.”

Furthermore, Petra also appeared to enjoy the convenience of using her phone or iPad to capture important moments by taking photos of them to later share with parents on ClassDojo:

I am very lucky that I have ClassDojo on my phone and on my iPad so I could try to mostly use my iPad, but if needed, I could quickly grab my phone. If I had to, like if we were on a walk, and I forgot my iPad, I always have my phone on me…So I am happy to be able to quickly grab my phone and grab that moment…We put all of these pictures on ClassDojo and I was happy that we got them and the parents also got to see them too.

From a parental perspective, Alba described the benefit of leveraging photos shared by the teacher on ClassDojo as a springboard for conversation with her daughter about her school day:

We use ClassDojo. I think that it’s nice to be able to use that tool to communicate with the teacher specifically to see photos of what’s happening in the classroom because we can’t be in the classroom, and you can’t be there for special events. So having the photos to be able to look at is nice, and then also [my child] will come home and tell us what’s happening in the picture. So, she likes to look at the pictures. It kind of triggers her memory of like, “oh, yeah, I did that.” Because if you asked her how her day was, she just kind of says, “it was good. I liked everything.” So when she has the picture to direct her, she likes to talk about it, like what she did with her friend.

Nancy also believed that videos posted on ClassDojo provided a window into what the children were doing in the classroom in “real time”:

The videos are great because then [you can see] the overall dynamic of what is happening in the room like who they are engaging with in real time.

ClassDojo as a Valuable Digital Platform for Building Strong Teacher-Parent Partnerships

Both the teacher and parents perceived ClassDojo as a valuable platform for communicating digitally and building strong partnerships with each other. From a teacher’s perspective, Petra described how the ClassDojo provided the opportunity for her to share the children’s learning with and receive feedback from parents:

I love seeing that the parents viewed them or they wrote a message back to me like, “love it” or something about what they just did. So I like that they got my message and they sent me a message back as well.

From a parental perspective, Alba, Danielle, and Nancy all concurred that ClassDojo was a space where they could support the teacher’s efforts and build positive parent-teacher partnerships. For instance, Alba was motivated to correspond with the teachers on ClassDojo to show appreciation for her efforts of taking and posting photos by commenting on them and being more “present in the online space” to build a positive partnership with the teacher:

Just making a comment on a photo… because it takes a lot of energy for a teacher to take all those photos and then post all of the photos… knowing that a teacher puts so much time and effort into something for it to feel seen and valued. I think that I am looking into the future if I could see how the relationship is built. I think that depends on me being vocal as a parent, and being present in that online space, because that’s really all we have.

Similarly, Danielle described how she appreciated the teacher’s efforts by responding to posts on ClassDojo: “I do click like on the majority of the pictures [posted on ClassDojo] just to let the teacher know they are valuable.” Nancy explained that the design of ClassDojo as a social media-like platform allowed parents to react and comment on the photos posted with positive responses as an encouragement to the teacher:

There were days when there were multiple like photos throughout the day. I am always one of the first ones who like just be happy to see… it’s because obviously ClassDojo is designed the way that Instagram was designed with “like” or “comment”… that’s the thing that we naturally do and as far as being ClassDojo…[saying] “yes I agree, yes I’m happy that you posted a picture.” It’s a way for the person posting the photos [to feel] encouraged… to post more pictures because I am happy to see them.

The Use of Limited Functions of ClassDojo as a Digital Communication Platform

Despite the benefits of ClassDojo as a valuable digital platform for promoting proactive parent involvement and for building positive teacher-parent partnerships, it appeared that both the teacher and parents utilized it only for basic and mostly unidirectional communication functions and that there were no shared expectations of how ClassDojo could and should be used. For instance, Nancy shared that she did not use ClassDojo to communicate with the teachers because she was unclear about their use of ClassDojo.

I do not rely on ClassDojo [to communicate with the teachers] because I honestly don’t even know how often teachers are checking it or if they are comfortable with being on it.

Danielle also noted the challenge of specifically not knowing how to use the private messaging feature of ClassDojo:

I had this ability to text a teacher through ClassDojo like private messages. I didn’t know how to use it so it would be very frustrating. I just kind of missed a piece of information technology.

The analysis of the digital communication artifacts on ClassDojo over the course of the summer program also confirmed that this digital platform was used limitedly. It was primarily used by the teacher to share photos and the parents to respond with a like. As summarized in Table 3, most notably, Petra posted 48 photos of children engaging in learning activities that received 76 likes and one positive comment from parents. Petra also posted 71 individual messages and two group messages to the parents, all were informational in purpose that did not require reciprocal communication from parents.

Discussion

To curb the transmission of COVID-19, unlike the pre-COVID-19 arrangements, parents were not permitted to be inside the classroom or meet with teachers face-to-face at this research childcare center when it was reopened for in-person instruction in Summer 2021. Accordingly, the communication between teachers and parents occurred solely digitally. Operating within the constraints and opportunities afforded by this digital world, digital technologies have, in turn, shaped the communication practices of both teachers and parents. This study was unique because it provided a window into the ways in which the classroom teacher and three parents navigated the digital communication terrain to begin fostering strong partnerships. The findings support Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory, attesting to the importance of the mesosystem (linking two microsystems, namely teachers and parents) in children’s education. Specifically, this study revealed some important findings concerning the process of building positive teacher-parent partnerships linked to the digital modes of communication, digital communication practices, limitations associated with digital communication, and the use of ClassDojo as a digital platform.

Email, Text, and ClassDojo as the Most Prominent Modes of Digital Communication

It was revealed that both the teacher and parents relied on emailing, texting, and ClassDojo as the primary modalities of communication. The finding regarding the use of digital technologies to facilitate teacher-parent communication is consistent with the evidence from other research studies (e.g., See et al., 2020; Thompson, 2008; Thompson, 2009; Thompson et al., 2015), uncovering especially that email is the most common digital means utilized for communication between teachers and parents. Just like what Thompson et al., (2015) found in their study, the parents in this investigation appeared to use email frequently to communicate with the teacher because it was convenient and asynchronous in nature, and easily accessible (e.g., via a smartphone). Additionally, the finding of parents’ preference for text messaging via smartphone with the teacher corroborates that of previous studies revealing the prevalent use of text messaging for teacher-parent communication (e.g., See et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2015). Furthermore, it appeared that ClassDojo was an effective mechanism for promoting proactive parent involvement because parents were able to leverage the photos and videos shared by the teacher on ClassDojo to spark conversations with their child. This finding supports that of Bahceci’s (2019) study, suggesting that ClassDojo helps to increase parents’ involvement in their children’s education and further facilitate teacher-parent communication.

The Nature of Digital Communication

Overall, this study revealed that the leverage of email, text, and ClassDojo as main digital means for communication helped enhance proactive parent involvement and foster positive teacher-parents partnerships. This finding aligns with Epstein’s (1995, 2016) idea about communication being a critical aspect of parent involvement. Furthermore, as digital technologies (e.g., emailing, texting via smartphone) are relatively convenient and are becoming readily available, they can encourage efficient and effective communication and partnerships between teachers and parents (Bordalba & Bochaca, 2019; Kuusimäki et al., 2019a, b; Olmstead, 2013; Wasserman & Zwebner, 2017). In this study, the teacher made concerted efforts to communicate materials (e.g., information, videos, photos) with the parents and the parents responded with appreciation. This finding resonates with that of previous studies suggesting that when teachers intentionally establish communication with parents, the parents are likely to feel more connected to the teachers and become more engaged in their children’s education (e.g., Bahceci 2019; Green et al., 2007; Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2005).

The Limitations of Digital Communication

Digital technologies have rendered affordances of convenience and efficiency, especially for busy working teachers and parents (Olmstead, 2013; Rogers & Wright, 2008; See et al., 2020; Thompson, 2008, 2009; Thompson et al., 2015). However, the parents in this study found digital communication to lack the kinds of personal connections and interactions that could only be afforded by face-to-face communication (e.g., teacher-parent meetings, parent volunteering opportunities in the classroom). Relatedly, the parents felt that it was more challenging to build teacher-parent partnerships through digital communication because it was devoid of “personable” and “personal” human connections. This finding cements the importance of face-to-face communication in what has been known as optimal in fostering constructive parent-teacher relationships (Chen, 2016; Decker & Decker, 2003; Wasserman & Zwebner, 2017). Furthermore, the perceived experiences of digital communication among the teacher and parents in this study appeared to solidify two realities: (1) digital technologies could make communication easier and more efficient, and (2) no digital media, however effective and efficient, could supplant traditional face-to-face, two-way communication so foundational to building positive human interactions and relationships.

Learning to Communicate via ClassDojo

The affordance of various digital technologies has helped promote innovative means by which teachers and parents communicate with each other and access shared information. The utilization of ClassDojo may be considered as such an innovative communication mechanism. Bahceci’s (2019) study demonstrated that the use of ClassDojo was effective in increasing parents’ engagement in their children’s education. In this study, although both the teacher and parents made intentional efforts to support each other’s involvement in the children’s education via digital communication on ClassDojo, there appeared to be no shared expectations of the ways in which ClassDojo should be utilized to optimize communication. It may be because both the teacher and parents had not received any formal training from the childcare center or elsewhere concerning the utilization of ClassDojo. Instead, they were all exploring and experimenting with the use of ClassDojo on their own. Consequently, it did not seem that the teacher and parents were using ClassDojo to its full potential because they appeared to have used it limitedly for basic communication purposes.

In this study, while finding it convenient to communicate with the parents via ClassDojo using her mobile devices (smartphone and iPad), the teacher leveraged ClassDojo to mainly share photos capturing the children’s learning products and engagement in activities as well as communicate generic information to parents. This finding was further confirmed by the analysis of the digital artifacts posted on ClassDojo, suggesting that both the teacher and parents had only begun exploring this new digital communication platform and thus used it limitedly. For instance, the parents’ engagement with ClassDojo was limited to mostly commenting with likes on photos to express support for the teacher’s efforts to take and share them so that they might feel connected to what the children were doing and learning. The teacher did find such an expression of appreciation encouraging. Thus, although the teacher and parents used ClassDojo for limited functions, the ways in which they capitalized on ClassDojo for communication appeared to be effective in their efforts to begin building positive teacher-parent partnerships. To further strengthen such partnerships, however, it would require a deliberate commitment of both the teacher and parents to continue engaging in positive communication and interaction with each other over a longer period of time than the two months afforded by the summer program. In fact, it has been recognized that a fundamental element of successful partnerships between teachers and parents is their efforts to engage in continuous, efficient, and effective communication (Chen, 2016; Epstein, 1995; Epstein et al., 2018; Ho et al., 2013).

On the one hand, the findings related to the utilization of ClassDojo as an innovative digital communication channel between the teacher and the parents appeared to demonstrate their mutual genuine efforts to build strong teacher-parent partnerships for the benefit of children’s learning and development within the constraints imposed by COVID-19. On the other hand, these findings suggest that leveraging ClassDojo for effective communication is a complex endeavor because it requires knowledge, skills, and positive dispositions to use this digital platform to its full potential. In essence, this reality highlights the need for professional development on digital communication for both teachers and parents. For instance, in this study, both the teacher and parents would have benefitted from professional learning to effectively utilize various features of ClassDojo for digital communication. They might have then established mutual understanding and expectations of such use. In turn, they might have also learned to engage in deeper and more extensive interactions beyond just sharing and liking posts. For instance, via ClassDojo, the teacher could share specific observations of the child’s learning progress, while encouraging parents to share details concerning the child’s unique developmental characteristics and learning needs. Through such exchanges, both the teacher and parents could then use the shared information to better work with the child. This bidirectional communication can potentially help deepen an authentic parent-teacher partnership and thereby enhance the child’s educational experience in the process (Chen, 2016; Epstein, 1995, 2016).

Educational Implications

As effective communication is at the very heart of strong teacher-parent partnerships, it needs to be continously spotlighted as an essential dimension of educational practices. Furthermore, in this digital era, the digitalization of communication in educational practices has become increasingly inevitable and even preferable to some. Technology-mediated communication affords parents the convenience and efficiency to participate proactively in their children’s education without being physically present at the school. However, this communication format requires both teachers and parents to be competent users of digital technologies. To help teachers and parents develop and enhance their digital competence, it is imperative that schools prioritize professional development for teachers and workshops for parents to learn about and put into practice the various functions of new digital technologies (e.g., ClassDojo) used by the school for reciprocal communication. Such professional learning opportunities can potentially help mitigate digital challenges and encourage both teachers and parents to become more fluent consumers and creators of technology-mediated communication (Bordalba & Bochaca, 2019: Palts & Kalmus 2015). As revealed by this study, the COVID-19-induced educational circumstances have compelled teachers and parents to engage in digital communication as an innovative alternative approach to face-to-face communication. Even when traditional face-to-face communication fully resumes post-COVID-19, competence in digital communication will only become all the more pivotal in fostering effective teacher-parent partnerships in the future presented with an ever-increasing array of digital technologies and media at our disposal.

Limitations of This Study and Directions for Future Research

This study has methodological limitations that should be considered in future research. We note two main ones here. The first one concerns the small sample size, consisting of only one teacher and three parents of young children in one classroom from a private childcare center. Given this contextual factor, it is understood that the sample is not representative of the larger population, and likewise, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations, especially those with dissimilar characteristics. Future research should consider examining a larger and more diverse sample of teachers and parents of young children to potentially confirm or add new insights to the investigation of teacher-parent communication and partnerships, especially when the educational process returns to “normalcy” post-COVID-19.

Second, given that all of the parent participants were mothers, it is unclear the extent to which fathers may communicate digitally with teachers. Previous research (e.g., Brown et al., 2011; McBride et al., 2002) has revealed child characteristics as related differentially to parent involvement between fathers and mothers. Future research might consider recruiting not only mothers but also fathers to discern potential gender similarities and/or differences in the nature of their communication with teachers.

References

Abubakari, Y. (2020). Perspectives of teachers and parents on parent-teacher communication and social media communication. Journal of Applied Technical and Educational Sciences, 10(4), 5–36. https://doi.org/10.24368/jates.v10i4.184

Aviva, D., & Simon, E. (2021). WhatsApp: Communication between parents and kindergarten teachers in the digital era. European Scientific Journal, 17(12), 1. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2021.v17n12p1

Bahceci, F. (2019). The effects of digital classroom management program on students-parents and teachers. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 11(4), 160–180. https://doi.org/10.15345/iojes.2019.04.012

Barnett, M. A., Paschall, K. W., Mastergeorge, A. M., Cutshaw, C. A., & Warren, S. M. (2020). Influences of parent engagement in early childhood education centers and the home on kindergarten school readiness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.05.005

Bassok, D., Michie, M., Cubides-Mateus, D. M., Doromal, J. B., & Kiscaden, S. (2020). The divergent experiences of early educators in schools and child care centers during COVID-19: Findings from Virginia. EdPolicyWorks at the University of Virginia. https://files.elfsightcdn.com/022b8cb9-839c-4bc2-992ecefccb8e877e/710c4e38-4f63-41d0-b6d8-a93d766a094c.pdf

Bordalba, M. M., & Bochaca, J. G. (2019). Digital media for family-school communication? Parents’ and teachers’ beliefs. Computers & Education, 132, 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.006

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2),77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner, & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 793–828). Wiley

Brown, G. L., McBride, B. A., Bost, K. K., & Shin, N. (2011). Parental involvement, child temperament, and parents’ work hours: Differential relations for mothers and fathers. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(6), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.08.004

Chen, J. J. (2016). Connecting right from the start: Fostering effective communication with dual language learners. Gryphon House

Chen, J. J. (2022). Self-compassion as key to stress resilience among first-year early childhood teachers during COVID-19: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 111.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103627

Chen, J. J. L., Chen, T., & Zheng, X. X. (2012). Parenting styles and practices among Chinese immigrant mothers with young children. Early Child Development and Care, 182(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15619460

ClassDojo: https://www.classdojo.com/about/

Colombo, M. (2016). Introduction to the special section. The digitalization of educational practices: How much and what kind? Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 8(2), 1–10. https://doi10.14658/pupj-ijse-2016-2-1

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage Publications

Decker, L., & Decker, V. (2003). Home, school, and community partnerships. Lanham: Scarecrow Press

Epstein, J. L. (1995). School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children we share. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 701–712

Epstein, J. L. (2016). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429493133

Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S. B., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. C., Jansorn, N. R. … Williams, K. J. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action. Corwin Press

Erdreich, L. (2021). Managing parent capital: Parent-teacher digital communication among early childhood educators. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 13(1), 135–159 https://doi.org/10.14658/pupj-ijse-2021-1-6

Galindo, C., & Sheldon, S. B. (2012). School and home connections and children’s kindergarten achievement gains: The mediating role of family involvement. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.05.004

Green, C. L., Walker, J. M. T., Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (2007). Parents’ motivations for involvement in children’s education: An empirical test of a theoretical model of parental involvement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 532–544 https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.532

Ho, L., Hung, C., & Chen, H. (2013). Using theoretical models to examine the acceptance behavior of mobile phone messaging to enhance parent-teacher interactions. Computers & Education, 61, 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.09.009

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M. T., Sandler, H. M., Whetsel, D., Green, C. L., Wilkins, A. S., et al. (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1086/499194

Karapanos, E., Teixeira, P., & Gouveia, R. (2016). Need fulfillment and experiences on social media: A case on Facebook and WhatsApp. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(b), 888–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.015

Kelty, N. E., & Wakabayashi, T. (2020). Family engagement in schools: parent, educator, and community perspectives. Sage Open, 10(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/215824402097302

Kraft, M. A., & Rogers, T. (2015). The underutilized potential of teacher-to-parent communication: Evidence from a field experiment. Economics of Education Review, 47, 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.04.001. 0272–7

Laho, N. S. (2019). Enhancing school–home communication through learning management system adoption: Parent and teacher perceptions and practices. The School Community Journal, 29(1), 117–142

Laxton, D., Cooper, L., & Younie, S. (2021). Translational research in action: The use of technology to disseminate information to parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Educational Technology: Journal of the Council for Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13100. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13100Advance online publication

McBride, B. A., Schoppe, S. J., & Rane, T. R. (2002). Child characteristics, parenting stress, and parental involvement: Fathers versus mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 998–1011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00998.x

Kuusimäki, A. M., Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L., & Tirri, K. (2019a). Parents’ and teachers’ views on digital communication in Finland. Educational Research International, 7, 8236786. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8236786

Kuusimäki, A. M., Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L., & Tirri, K. (2019b). The role of digital school- home communication in teacher well-being. Frontiers in psychology, 2257. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02257

NAEYC (2019). NAEYC early learning program accreditation standards and assessment items. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/accreditation/early-learning/standards_assessment_2019.pdf

NAEYC (2020). Developmentally appropriate practice. Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/dap-statement_0.pdf

Nagasawa, M., & Tarrant, K. (2020). Who will care for the early care and education workforce? COVID-19 and the need to support early childhood educators’ emotional well-being. CUNY. New York Early Childhood Professional Development Institute. https://educate.bankstreet.edu/sc/1

Olmstead, C. (2013). Using technology to increase parent involvement in schools. TechTrends 57, (6), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-013-0699-0

Palts, K., & Kalmus, V. (2015). Digital channels in teacher–parent communication: The case of Estonia. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 11(3), 65–81

Patrikakou, E. N. (2016). Parent involvement, technology, and media: Now what? School Community Journal, 26(2), 9–24. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1123967.pdf

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Randall, K., Ford, T. G., Kwon, K. A., Sisson, S. S., Bice, M. R., Dinkel, D., & Tsotsoros, J. (2021). Physical activity, physical well-being, and psychological well-being: Associations with life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic among early childhood educators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 9430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189430

Reay, D. (1995). A silent majority?: Mothers in parental involvement. Women’s Studies International Forum, 18(3), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-5395(95)80077-3

Rideout, V. (2017). The Common Sense Census: Media use by kids age zero to eight. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/research/report/csm_zerotoeight_fullreport_release_2.pdf

Rogers, R., & Wright, V. H. (2008). Assessing technology’s role in communication between parents and middle schools. Electronic Journal for the Integration of Technology in Education, 7(1), 36–58

See, B. H., Gorard, S., El-Soufi, N., Lu, B., Siddiqui, N., & Dong, L. (2020). A systematic review of the impact of technology-mediated parental engagement on student outcomes. Educational Research and Evaluation, 26(3–4), 150–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2021.1924791

Thompson, B. (2008). Characteristics of parent-teacher E-mail communication. Communication Education, 57(2), 201–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520701852050

Thompson, B. (2009). Parent-teacher e-mail strategies at the elementary and secondary levels. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, 10(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17459430902756203

Thompson, B. C., Mazer, J. P., & Flood Grady, E. (2015). The changing nature of parent-teacher communication: Mode selection in the smartphone era. Communication Education, 64(2), 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1014382

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start, National Center on Parent, Family, and Community Engagement (2018). Head Start Parent, Family, and Community Engagement Framework. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/pfce-framework.pdf

Wasserman, E., & Zwebner, Y. (2017). Communication between teachers and parents using the WhatsApp application. International Journal of Learning Teaching and Educational Research, 16(12), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.16.12.1

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the teacher and three parents whose participation made this study possible. We also thank the editor and peer reviewers for their time and expertise in reviewing this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Appendix A

Core Interview Questions

For parents

-

(1)

How do you feel about parent-teacher communication?

-

(2)

Have you used any digital technology to communicate with your child’s teacher? If so, what kinds?

-

(3)

How do you use digital technology to communicate with your child’s teacher?

-

(4)

How often do you actually use digital technology to communicate with your child’s teacher?

-

(5)

How do you feel about using digital technology to communicate with your child’s teacher?

-

(6)

In comparison to in-person participation, how involved have you been in using digital technology to communicate with your child’s teacher, and why?

-

(7)

Have you encountered any issues with digital technology while using it to communicate with your child’s teacher?

-

(8)

Do you think technology has helped you build a strong partnership with your child’s teacher? Please describe your experience.

For teachers

-

(1)

How do you feel about parent-teacher communication?

-

(2)

Have you used any digital technology to communicate with the parents? If so, what kinds?

-

(3)

How do you use digital technology to communicate with the parents?

-

(4)

How often do you actually use digital technology to communicate with the parents?

-

(5)

How do you feel about using digital technology to communicate with the parents?

-

(6)

In comparison to in-person participation, how involved are you in using digital technology to communicate with the parents, and why?

-

(7)

Have you encountered any issues with digital technology while using it to communicate with the parents?

-

(8)

Do you think technology has helped you build strong partnerships with the parents? Please describe your experience.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Rivera-Vernazza, D. Communicating Digitally: Building Preschool Teacher-Parent Partnerships Via Digital Technologies During COVID-19. Early Childhood Educ J 51, 1189–1203 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01366-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01366-7