Abstract

Due to the emergence of new forms of preschools and parents’ increased freedom of choice regarding early childhood education, more research on parental preschool preferences is needed. Although preschool offers a seedbed for the development of knowledge and competencies, this development matures through interaction with parents. Therefore, parental expectations and wishes are very likely to affect children’s learning. The mobile preschool is a new form of educational practice in Sweden where children travel by bus to different places for play and learning. This form of preschool can potentially lay a foundation for social and ecological sustainability because children learn to meet diverse people, explore different places, and spend time in nature. We interviewed 15 parents of children in a mobile preschool, most from a middle-class background. The main aim was to explore how these parents explain their choice of this type of preschool. Another aim was to identify desirable competencies that the parents think their children will achieve through the mobile preschool. Six themes related to preschool choice were identified; of these themes, “being out in nature” and “enlarging the children’s reality” were the most prominent. Two clusters of competencies were distinguished: care- and cooperation-oriented competencies, and freedom- and independence-oriented competencies. After analyzing these results in relation to two current educational discourses—education for sustainable development and entrepreneurship in a neoliberal society—we show how parents participate in reproducing these discourses. These findings add novel and important knowledge to the field of early childhood educational practices concerning parental choice and preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research on parental reasoning regarding choice of preschool and on parental preferences regarding preschool practices has increased in recent years (Ceglowski 2004; Karlsson et al. 2013; Nisskaya 2018; Rose et al. 2013). In comparison with the literature on parental choice of school, however, the number of studies is still relatively small. At the same time, new research in this field is urgently needed due to both the continual emergence of new forms of preschool and the increased freedom parents have in choosing a preschool. Although school and preschool offer a seedbed for the development of knowledge, values, and competencies, a child’s values and norms about “being a good citizen” evolve in interactions with parents (Hayward et al. 2015). Therefore, parents’ wishes for a preschool are likely to affect the outcome of that preschool’s practice (see Borg 2017).

The “mobile preschool” is a relatively new form of preschool in Sweden in which children (aged 3–5) travel on a daily basis with their teachers by bus to different places, where they play and learn, often in an outdoor environment (Ekman Ladru and Gustafson 2018). This form of preschool can potentially lay a foundation for an active citizenship, because the children learn to meet different people and encounter a wide range of places (Gustafson and van der Burgt 2015). These opportunities are vital, since the increased segregation in Sweden has resulted in divided cities where children from different backgrounds rarely meet. However, there is a lack of research on how the parents of children in a mobile preschool reason about their choice of preschool.

In this study, we interview 15 parents of children in a mobile preschool, most of whom come from a middle-class background. The aims of this study were to explore how the parents reason about their choice of this specific form of preschool and to identify various desirable competencies that the parents think their children will achieve by being part of the mobile preschool. The results of the interview study are then analyzed and discussed in relation to theories about competency-based education and theories and studies about education for sustainable development and entrepreneurial learning in a neoliberal society.

The Mobile Preschool: A New Pedagogical Practice

Starting about a decade ago, a new form of early childhood education and care practice was developed in Sweden: namely, mobile preschools, which are preschools in buses that take children to a variety of public spaces. A mobile preschool is usually organized as one division of a stationary preschool. The bus accommodates about 20 children and three teachers, one of whom also works as the bus driver. The children are in the mobile preschool Monday to Friday, from 9 am to 3 pm; depending on their parents’ work schedules, the children also attend the stationary preschool before and after bus hours. The bus has been re-modeled and equipped with a toilet, a kitchenette, and seats arranged in groups of four around small tables. Learning materials such as books, materials for arts and crafts, outdoor toys, fishing gear, and so forth are stored in boxes inside the bus and in the luggage compartment under the bus.

Earlier research on mobile preschools (Ekman Ladru and Gustafson 2018; Gustafson and van der Burgt 2015) shows that outdoor activities are performed in all four seasons. During the winter months, children wear snowsuits usually made of thick, durable, and water-repellent fabrics (for illustrations see Supplementary file 1). If temperatures drop below minus 10 degrees Celsius, the duration of outdoor activities is usually short. On these occasions, teachers usually choose indoor activities (in the heated bus, at a museum, or in another indoor space). There are currently 40 preschool buses in 14 municipalities around Sweden (Gustafson et al. 2017).

Mobile preschools were initially a way for Swedish municipalities to solve a lack of preschool spaces; however, this form of preschool includes the possibility of new learning environments. In an interview study with civil servants at municipalities containing one or more mobile preschools, two main themes were identified regarding the purpose of the mobile preschool. The first theme concerned experiential learning, as the preschool enables the children to learn in different and creative ways by visiting diverse places (Gustafson et al. 2017). Here, the main focus is the opportunity for children to be out in nature, which is seen as promoting motor skills, good health, and more traditional cognitive learning. Having the children learn to care for nature is also vital. The second theme concerned integration and societal participation, as the mobile preschool can be seen as a tool to integrate children and teach them to participate in society, thereby potentially promoting social sustainability.

Previous Research About Parental Choice of Preschool and School

Earlier research about parental choice of preschool and school has shown that emotional and moral concerns are involved in the process of choice. Making a good choice for one’s child is seen as an important part of being a good parent (Karlsson et al. 2013). Not all parents trust preschools to care for their children’s needs and education; thus, it is important for parents to show that they have actively chosen a preschool that is regarded as being able to meet their child’s needs. In addition to personal, interpersonal, and socio-economic factors, Kyprianos (2007) found that parents make choices based on traditions and discourses in their specific country—or in the Western world at large—about what factors characterize good early childhood care (see also Hayes 2007).

Rentzou (2013) reviewed studies on parental preferences regarding preschool practices in different countries and found that these preferences seem to be characterized by a dichotomy where either education or care is the focus; furthermore, there is often a stronger focus on care and interaction, especially among middle-class parents (see Rentzou 2013; Shlay 2010). One way to bridge this dichotomy between care and education and to gain a deeper understanding of parental reasoning is to go beyond quantitative studies that ask parents to rate a list of factors according to what they consider important. We do this by conducting qualitative interviews that can reveal complex patterns of reasoning. We analyze our empirical material using a theoretical approach about competency-based learning in which care-based practices and cognitive learning are seen as intertwined. Our results will also be discussed in relation to two educational discourses that are common in Sweden: education for sustainable development and entrepreneurial learning in a neoliberal society.

Competency-Based Learning

A competency-based learning approach moves beyond the dichotomy of caring (i.e., emotions) and education (i.e., cognition) by acknowledging that the real-life challenges people must confront are complex and demand both emotional and cognitive skills, as well as practice-based skills (Moran-Ellis and Tisdall 2019). This approach also recognizes that these dimensions are not separate but intertwined, and that they can be summarized in various key competencies such as interpersonal competency, creativity, and system thinking (Wiek et al. 2011). Key competencies can be seen as educational learning outcomes—that is, as complex capacities that will help children deal with difficult challenges in the future. Although there is still no clear definition of the concept of “competency,” a common way to describe it is as “an integrative whole of knowledge, skills, and attitudes” that is needed to deal with complex real-life situations in specific areas such as sustainable development or business life (Biesta 2015; Moran-Ellis and Tisdall 2019).

One good example of competency-based learning in preschools is social-emotional learning. This approach acknowledges that social and emotional aspects of preschool are important for early school success, in addition to cognitive aspects. It is often based on attachment studies in developmental psychology that show that early close relations with others are important for later independence and school performance (Denham et al. 2014). Competency-based learning lays the foundation for various complex competencies that are important later on in life.

Education for Sustainable Development

In Sweden, education for sustainable development (ESD) is an important part of the whole educational system. The sustainable development concept contains three aspects: the economic, ecological/environmental, and social dimensions and in order to achieve a sustainable society, all of these aspects must be integrated (Elliott 2013). Due to this complexity, ESD often focuses on developing different competencies such as system thinking, interpersonal competencies, and anticipatory competencies (Wiek, Withycombe and Redman 2011).

The national curriculum for early childhood education in Sweden declares that all preschools should ensure that each child develops respect and care for all forms of life and for the surrounding environment, and that they should work with democratic values (The Swedish National Agency for Education 2018). In addition, researchers in the field of early childhood ESD argue that it is essential to focus on caring for oneself, for others, and for the world in preschools, and that these aspects ought to be seen as integrated (Johansson 2009; Samuelsson 2011). Children should also be given the opportunity to develop creativity in order to be able to work toward a more sustainable future. Another important aspect is that parents are seen as important actors, since their attitudes often influence the outcome of ESD (Borg 2017). To summarize, it is seen as important in ESD to promote other-oriented values and a holistic view.

Entrepreneurship in a Neoliberal Society

In 2009, the Swedish government launched a strategy about the importance of entrepreneurship in education (Government Offices of Sweden 2009). This approach was based on a view that more people need to start businesses due to a global economic system that forces countries to promote competencies in their citizens such as creativity and enterprise in order to be able to compete. A more pedagogical basis for this strategy is the idea that entrepreneurial competencies can be learned, and therefore should be promoted as early as possible among children (Carrier 2005; Neck and Geene 2011). In the Swedish preschool curriculum, entrepreneurship is mentioned implicitly through statements about instilling curiosity, creativity, self-confidence, and interest in children by allowing them to gain new experiences (The Swedish National Agency for Education 2018).

Some theoreticians see this focus on entrepreneurship in the educational system as an example of an adjustment to an overarching neoliberal society (Axelsson 2017; Rose 1992). In a neoliberal society, the responsibilities that were once placed upon the state and on other societal institutions have instead been placed on the private business sector and on individuals, based on values of competition and self-interest (Davies and Bansel 2007). However, this self-interest should not be seen as the opposite of societal wellbeing, since in neoliberal thinking, every individual is seen as working to benefit society by obtaining entrepreneurial competencies and promoting economic wellbeing for all (Davies and Bansel 2007). In such a society, it is important for the educational system to promote highly individualized competencies that should help children become “entrepreneurial actors across all dimensions of their lives” (Brown 2003, p.38).

Besides direct regulation through policy documents, a neoliberal society steers and governs by creating new mentalities or discourses about, for example, what is important for children to learn (Davies and Bansel 2007). One way of governing that is particularly interesting from a preschool context that often involves social-emotional learning is to steer through emotions. For example, Ecclestone and Hayes (2008) criticize emotional learning by arguing that it focuses too much on positive emotion, wellbeing, and adaptation, which could, in the long run, undercut social criticism and instead turn the young into obedient consumers. Taken together, these ways of governing can influence a parent’s views on which aspects are most important to focus on when choosing a preschool.

Aim and Research Questions

In this study, we explore how the parents of children in mobile preschools reflect on their choice of preschool, with a focus on middle-class parents. The research questions are: (1) What factors are important in parents’ choice of preschool? (2) What competencies do they consider their children will receive by being a part of this type of preschool?

Method

Overarching Methodological Approach

We investigated preschool choice from a phenomenological perspective, where time dimensions are vital (see Langemar 2008). Making a choice about preschool is an ongoing process rather than one that occurs at a single point in time. Therefore, we explore parents’ memories about what made them choose this type of preschool in the first place (the past), what aspects cause them to keep their child in this preschool (now), and what competencies they think their child will gain from being in this preschool (the future). We see these time dimensions as intertwined. The present is influenced by the past, but also by future expectations. The present also influences how one remembers the past and perceives the future.

Participants and Procedure

Parents from five different mobile preschools in the Swedish towns of Lund, Örebro, Malmö, Uppsala, and Stockholm participated in the interview study. Ten of the parents were female and five were male, with ages between 25 and 41. The majority had a university degree or a comparable level of education. The interviews were semi-structured and ranged from 1 to 1.5 h (the interview guide can be found in Supplementary file 2). Semi-structured interviews are conducted as discussions around themes, and the order of the questions in the interviews is not completely fixed; rather, it can be changed according to how the conversation develops (Drever 1995). This gives a high degree of flexibility, which was fitting for the aim of this study. The interviews were recorded and transcribed word by word.

Analysis

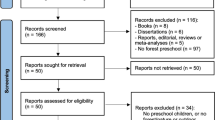

An inductive thematic analysis was performed by the first author (Braun and Clarke 2006). The results of this analysis were discussed by all three authors throughout the process. The inductive analysis was conducted in several steps, as follows: The first step was to read through each interview in order to identify different higher order themes. The research questions guided the analysis at each step (Langemar 2008). The next step was to go through all the interviews and attempt to fit blocks of text into one of the themes. The theme was noted in the margin of the transcription along with other comments. Thereafter, the blocks of text were cut out of the individual interviews and ordered under the higher order themes in separate documents. A search for subthemes and relations between themes was performed. Illustrative quotations, representative of the themes, were chosen. After the inductive analysis was finished, the different themes were reorganized into two overarching clusters and analyzed in relation to fitting theoretical approaches and related studies. The theories were identified inductively—that is, after the first data-driven analysis. Thus, the first inductive analysis stayed rather close to the data, while we in the second step lifted the analysis to a more abstract level by relating it to theories (see Langemar 2008).

In regard to the two research questions, we perceive the second question on competencies to be a sub-question to the first question on what factors are important in parents’ choice of preschool. This is because the question of which competencies parents consider their children will receive is intertwined with and inseparable from the reasons behind their choice of preschool. Therefore, we analyze these two aspects together in the following section.

Results

The First Contact

With regards to how the parents first came in contact with the mobile preschool, the first and most common aspect is the good social reputation of this type of preschool. Many of the parents mentioned that the main reason why they started thinking about choosing the mobile preschool was that their friends and neighbors had spoken so positively about it; other parents that had their children in this type of preschool were very satisfied. This made them consider trying it out. This choice was further promoted if a friend of their child was about to move to this type of preschool. Parents who had decided to place a second child in this type of preschool also mentioned the importance of their earlier positive experiences.

…also, the neighbors’ kids went there and they’re the same age, and they were really happy with it, so it’s mainly from the neighbors we’ve been hearing about it… And everyone I’ve heard from has been pleased with it… (INT 2)

…I have some friends who’ve had their kids on the bus. And we thought it sounded exciting, so that’s how we ended up doing it. (INT 13)

A second subtheme is that the pedagogues at their child’s earlier preschool recommended the mobile preschool; the preschool teachers thought that the child would “fit” in this type of preschool due to some personal characteristic such as liking to move a lot. In these cases, the parents often mentioned that this recommendation was also based on practical aspects related to, for example, a lack of space in the ordinary preschool. Two of the parents claimed that the pedagogues simply informed them that their child would be moved to this type of preschool, and that they passively accepted the change. However, the parents later realized that this type of preschool suited their child.

…when he was younger, one of the teachers in that unit recommended that we apply to get him in there. Because he is very physically active and curious, and according to her…she thought it would be a beneficial option for him. (INT 15)

It started with—what should I say?—us getting tips from or being asked by staff in the preschool unit she attended previously if we’d be interested in getting her on the bus, where she is now. And I believe this was related to the fact that there were…that there was going to be a lot of new kids coming to the unit she was attending. (INT 5)

The third subtheme is about some kind of disruption that caused the parents to choose the mobile preschool. One parent stated that the earlier preschool was affected by mold; thus, the parents were forced to choose a new preschool, and it was easier for them to quickly get a place for their child on the preschool bus. Another parent mentioned that the previous preschool was unsatisfactory. After the initial disruption, the parents’ decision to move their child was based on arguments similar to those mentioned above; that is, the mobile preschool was the most convenient choice or that the parents had heard many good things about it.

It was because we switched to a new preschool. The one he was attending had mold issues and we had to go to a new preschool. And there, they said, “Well, it’s easiest to get a place if you choose the bus.” (INT 3)

Actually, the main reason was that they couldn’t accommodate his moving up to the three-year-olds group…So I preferred to have him in a group of kids of the same age. So it ended up being the preschool bus. (INT 6)

Enlargement of Reality

One of the most prominent themes—regarding both the initial decision to choose the mobile preschool and the reason why parents chose to keep their child there—can be summarized as the enlargement of reality that this type of preschool provides. The first and most common subtheme concerns the variation in experiences children have due to the many things they experience when traveling to new and different places every day. Some parents—although not many—also mentioned as a benefit the many meetings the children can have with different people who live in different circumstance than they do themselves.

The parents’ stories focused on quantity rather than on quality. Words such as more, much, and many were used frequently. Furthermore, the emphasis was on the novelty of the experiences, along with the variation, discovery, excitement, fun, and adventure the children could experience. The parents compared the mobile preschool with other forms of preschools that they described as repetitive, monotonous, and dull in comparison. In the mobile preschool, their child is not confined to the same place day in and day out, and does not get caught up in boring routines.

…my impression at any rate is that they get to try out a lot more things than a kid at a regular daycare would. And I think it’s good to get to try out as much as possible, and I believe you learn from that…the kids do. (INT 13)

Well, it’s the fact that they get to see a lot of things. That is why I think it’s fun—they get to see lots of things. They’ve been able to experience and see so many things! When I was little I didn’t have that—I just had my little area. (INT 3)

…so I thought it must be really monotonous to have to be in the same rooms, the same playground, every day. And that with the bus you can create greater variety in the day-to-day experience. (INT 4)

The second subtheme is the sense of freedom, flexibility, and unpredictability that this specific type of preschool gives. For example, having the children visit places that are not built for children is seen as challenging in a positive sense, since they become prepared for the unexpected. Their world is getting bigger, and new spaces are opening up for them. The focus of this subtheme is more on the opportunities brought by the preschool than on things that have actually happened. The preschool brings the opportunity for novel pedagogical approaches, for the children to be included in choosing the places to go to, for adjustment to the children’s own interests, and for spontaneous decisions on where to go during the day. However, it is unclear how often these opportunities actually happen, since the parents do not have much insight into pedagogical issues or into how the choice of place is made.

… of course it’s more enclosed, and they get frustrated more easily, it seems to me, when they have to be inside and be limited by the available toys and so on. I feel that it’s a bit less constrained, there’s a bit more space. I believe that’s had a positive effect on them. (INT 11)

If they’re at the same playground, they get to know the environment after a while. But when they’re in different places, and places that were never built for kids to start with, they’re forced to explore, and learn, and adapt. (INT 5)

They’ve had a chance to decide for themselves that “today…” I mean, they can change the agenda to “We’ll go to this place instead and do something.”…they’re entirely mobile and can, like, do as they please…which I think is great. I don’t know how often they take advantage of this possibility. (INT 12)

Why then do the parents consider the two aspects mentioned above as benefits for their child? On the one hand, their stories reveal some desirable future competencies that they think their child will achieve: Independence is one competency that is mentioned spontaneously. The children become prepared for unexpected things and learn to handle such things more independently. The parents also stated that the many experiences promote imagination and creativity. Some parents spoke of their children developing a good traffic sense by traveling with the bus and experiencing real-life road situations. The parents also perceived place competency—that is, children developing a sense of different places, being able to recognize and name places. Some of the parents vaguely claimed that the children probably learn more due to the variety and the unexpected challenges. Only one parent mentioned that by meeting many different people, she hoped her child would become inoculated against prejudices about people that live different lives than themselves. Other parents viewed meeting new people as beneficial because it makes their child open, less shy, and more urban.

In addition to gaining different competencies, there were arguments for choosing this specific type of preschool that were based more on the parents’ own preferences, than on their children’s need; that is, the parent might like and have a need for excitement and for a variety of things to happen. The arguments were also sometimes based on providing compensation for things that the parents did not have the time to do, such as providing activities for children with a high energy level.

It’s not such a strict routine—I think that’s the best thing about it—that changes can happen. I like change. I’d like to have new adventures all the time. (INT 12)

They get to go to places that they don’t usually go to with their family. (INT 9)

The Unique Preschool Teachers

The quality of the preschool teachers was mentioned both as something that preceded the parents’ choice of preschool and as something that the parents continued to be satisfied with. The parents often mentioned that the pedagogues were extraordinary good. Two parents, however, did not mention this theme at all. In addition, the other parents did not elaborate on this aspect very much. Besides naming aspects that are common in other well-functioning preschools as well—such as the pedagogues interacting well with the children—the parents emphasized some specific qualities of the pedagogues in the mobile preschool.

Due to the special form of the preschool, the parents perceived the pedagogues as being extra dedicated to their work. The teachers have actively approached this form of preschool, and are viewed as more engaged than other preschool teachers, who are sometimes seen as more passive and routine bound. The parents also mentioned that it is good that this dedication results in the preschool teachers staying at the same workplace for a long time, which results in them being experienced, secure, and having well-developed working skills.

We met the teachers and we felt they exuded an incredible dedication and enthusiasm when we talked to them; it seemed like they were passionate about their work in a way we hadn’t encountered in regular preschool. So I guess it was that enthusiasm—that passion—that attracted us. (INT 1)

It was primarily the fact that they were passionate about their work, that it seemed like they had chosen…they had made active choices to get where they were, because they considered it an exciting kind of teaching. And they had sought out something different, not just a regular job that you’ve done for years on end, but that you actively seek out something that is a bit different, a job in which you can grow. (INT 14)

The second subtheme relates to the parents’ argument that due to the special form of the mobile preschool, it attracts pedagogues with specific personalities who tend to be more active, to not shy away from challenges, to be adventurous, to love nature, to be inventive, and to let the children do a lot of different things. Some of the parents also perceived the pedagogues as not being overly cautious; they do not worry about risks all the time, and grant the children some freedom. The children are allowed to test their limits, which is seen as promoting more independence; in a sense, the children become tougher.

The staff have been consistently really good, incredibly dedicated. And the outdoor teaching, and cool, entertaining women who have organized amazing activities for the children and so on. So it’s partly their personalities… (INT 11)

They’re extremely good, but it’s also that they enjoy…you get the feeling they have a good time with the children—they’re upbeat and cheerful in a good, wholesome way. (INT 8)

Related to these subthemes is that the pedagogues are seen as being satisfied with their work, being happy, and having a positive outlook. They are not negative and cranky. This is seen as a reason why the pedagogues interact with the children in such a good way. Their positive mood is passed on to the children, who also become happy and get into a good mood.

Being out in Nature a Lot

One of the most prominent themes in the parents’ stories was that they chose the mobile preschool and continue to keep their child/children there because it allows the children to be out in nature a lot—especially in the forest. Being out in nature is seen as something natural and as something that is unproblematically positive. Only one parent did not mention aspects directly related to this theme; most of the parents elaborated on this theme thoroughly.

The first subtheme is about the opportunity for natural play with things found in nature and without the need for fabricated toys. In addition, the parents considered that computers and electronic devices have taken over their children’s life-worlds too much; instead, they saw it as beneficial for the children in the mobile preschool to have the opportunity to play with natural things outside. Without prefabricated things and places that have been ready made for children, the children’s imagination is challenged and they hopefully become more creative in the future. Another aspect that some of the parents perceived as important was that play outside in nature seems to be less dependent upon traditional gender roles. Boys and girls play together and do not fall into masculine and feminine stereotypes as easily.

…but it’s also the kind of thing I find I hear many people say, and I guess I would agree, that by being in a place where they don’t have a lot of toys, but rather play with the things they find in the natural environment instead, that sparks the imagination. (INT 7)

…we’ve never really had access to the woods and to nature, that was something we wanted [for] our daughter, and then our son, to have access to every day. And it has so many advantages, too…that they spend less time playing with the toys at the preschool. Now, I wanted my daughter to play with sticks and stones just like all of the boys—without there being such a division between what girls play with and what boys play with. (INT 10)

The second subtheme concerns the opportunity for practical learning, instead of theoretical learning such as learning about nature from a book. This subtheme mainly refers to how the children learn a lot about nature when outside. They can touch, see, and feel nature. Through being in direct contact with animals and plants, the children learn the names of flowers, insects, butterflies, and so on. Some of the parents also mentioned that the children learn practical skills, such as how to cook over an open fire. Furthermore, they are seen as getting a good general education about nature that can benefit them in the future. Another aspect is that the children learn to take care of, and have respect for, animals and nature. They develop a sense of empathy. A few parents saw this as a first step toward an awareness about environmental issues in the future. Two parents also mentioned that the children get a better grasp about how humans are dependent upon nature. Some of the parents talked about a general outdoor pedagogy that can promote more traditional cognitive learning, such as mathematics, as children use stones and sticks to learn to count.

Yes, it’s part of nature. Outdoor teaching…

How do you view the concept of outdoor teaching?

Well now—plants and leaves. The names of the spruce trees, and the ants, and how they build their nests. Spiders. Basically, everything the outdoors can offer. How snow is formed. (INT 6)

So of course I’m hoping, or what I’m already sensing, that is, some sort of feeling for nature—that they learn they we need to take care of the natural environment, be a little environmentally aware, and that you don’t put garbage into the environment. (INT14)

In the third subtheme, the parents talked about how by being out in nature, their children become less reliant on convenience and less overly sensitive. These characteristics are perceived as being particularly good by parents of children who naturally like to stay inside. The children become more positive about things that are not particularly fun outside, such as being outside on a rainy or cold day, or about things that are somewhat risky, such as climbing. They learn to challenge their worries and handle risks in a concrete way. This is good because the children are seen as becoming more self-confident, self-reliant, and tough.

You shouldn’t protect children from everything, and it’s a pretty good thing for them to learn to actually…I mean that they learn…It’s a plus that both the parent and the teacher are modeling—in everything from “Look here—it’s a long way down to the ground,” or “It’s thorny around here. Be careful of that bush,” or, you know, whatever it might be. (INT 7)

And also the fact that they know what it’s like to not always be comfortable—that they get the idea that they should get used to being out in the woods, that there’s nothing odd about being outside and not getting wet, but that it…I mean, okay, but get used to it. Practice. (INT 4)

Aside from the competencies mentioned above, the parents in the fourth subtheme based their arguments on parent-oriented reasons such as nostalgia. This nostalgia related to how they themselves were out a lot in nature, especially in the forest, in childhood; they still love nature and view being out in nature as something that is generally healthy. Therefore, the parents also want their children to start to love nature. One parent mentioned that it is good if their children like nature, since it makes life easier if everyone in the family like to do the same things. The parents also viewed the preschool’s activities in nature as a compensation for the lack of nature contact in the families’ spare time. Since they live in the city and have a lot to do, they are unable to take their children out in nature as much as they would like to.

Well, that we have these areas of untouched nature…not all countries have wooded areas and other natural environments that you can experience as freely as we can. And it feels like a healthy place that I want…I want my children to enjoy being there because I do, and it’s a…I mean, it’s worth it. I myself have spent a great deal of time in the outdoors throughout my life and I want them to be able to do that, too. (INT 12)

Yes, definitely. But there’s also the fact that we live in the city and work long hours, and there’s no time to go…no time to go out into the woods and so on—like, often. Instead, we usually end up going to some downtown-area playground. But that these kids got the chance—they go to the seaside, and they go into the woods. (INT 14)

Physical Aspects

This theme is closely related to being out in nature a lot, although it can also be related to other factors such as being at a playground. Some of the parents perceived physical aspects as a main reason for choosing the mobile preschool. However, this theme was just briefly mentioned and was not elaborated on. Two parents did not mention these aspects at all.

The first subtheme involves the parents who perceived their child as being more physically active than most other children. Therefore, this preschool suits the child well. The child can be out in nature a lot and have a good outlet for inbuilt energy; there is more space, so the child can run around and climb. In this way, the child is perceived as more satisfied, happier, and calmer in other situations; therefore, the child also sleeps well.

He loves moving around. He likes all kinds of weather—he wants to be outdoors in any kind of weather. That was the thing—that that would suit him. (INT 6)

Because he is very physically active and curious, and according to her…she [the preschool teacher] thought it would be appropriate for him. For our child, he is very…he loves jumping and running, and his legs have been moving like drumsticks basically ever since he was born. So it’s pure…he has to have an outlet for his energy. (INT 15)

The parents perceived moving around a lot as something that was beneficial for children’s physical and psychological wellbeing. The children are less stressed when they have been outside moving all the time. The parents also argued that being outside in the fresh air promotes good physical health, since the children do not get colds and stomach flu as often as children who spend most of their time inside, in crowded spaces. In addition to the inherent benefit of children being infrequently sick, the parents perceived their children’s good health as a personal benefit that let them spend less time off work caring for a sick child. A third subtheme involves the children’s opportunity to develop their motor skills.

And it has so many advantages, too—the children get sick less often, since they’re outside so much. (INT 10)

They get fresh air. They don’t have to be shut inside stressing each other out. Hopefully sick less often. (INT 8)

I mean, regarding their physical and motor development, both of them have become much more capable than before. (INT 14)

Social Aspects

A final theme concerns the social aspects of being in the mobile preschool. Most parents—with only two exceptions—mentioned this theme, although they did not elaborate on it very much. Only one parent mentioned social aspects as an initial reason to choose this form of preschool; the other parents viewed social aspects as a benefit prompting them to keep their children in the same preschool.

In the first subtheme, the parents expressed their admiration of the advanced structure and order of activities taking place in the mobile preschool. Due to the freedom that this preschool offers, it is necessary for the pedagogues to compensate by maintaining strict rules regarding what children can do and not do; the activities can be quite structured, and the pedagogues keep an eye on the children. Furthermore, the small space in the buses and traffic safety requirements make it necessary for the children to keep their things in order and sit obediently in their specific places.

Plus, simply learning how to behave in a larger group. And that’s very much what the parents said—they were so incredibly impressed by the good behavior the teachers were getting from the children. And how unbelievably organized they were when they were out walking… (INT1)

Also, they are extremely well disciplined. If we can say that, but they seem…the children understand what is dangerous and what is okay and not okay—in terms of safety and so on. (INT 8)

This form of preschool demands that the children collaborate in an advanced way, by helping each other and by keeping watch over themselves and over other children so that, for example, no one is left behind in a forest area. The parents argued that this collaboration, along with the fact that there are not that many children, results in a tight group with a high degree of social cohesion, where everyone plays with everyone. In addition, some parents stated that their children are proud to be in an unusual type of preschool; the children compare themselves with children in other, more traditional, forms of preschool, and feel special. Thus, the core of this subtheme is that the children obtain a strong group identity.

Everyone in the group helps out. That way it happens naturally that, you know, some can’t get up and then the others, those who can, help them—they help each other…I believe they become closer to each other—in this group at least—though I don’t know how they behave toward others; but in any case, I believe they get better group cohesion in the bus. (INT 2)

They are very good at creating a strong sense of belonging and group identity in this group, which I believe is related to the fact that they spend a lot of time outdoors and they learn to be good friends and take care of one another. (INT 15)

“Mommy, I’m a ‘[name of the mobile preschool]-er’ now. I don’t want to go to [name of old preschool]”…and I think it’s great for her to feel that it is part of something different. (INT 10)

All of these aspects make the preschool psychologically safe and particularly good for children who are more active and who have a hard time concentrating and sitting still. The preschool form is seen as promoting social competency and social responsibility. This competency is related to helping others, but also involves children becoming less shy, daring to take over a place, making their voice heard, and becoming more “street smart.”

Discussion and Theoretical Analysis

In this section, we discuss and analyze the results of the inductive analysis in relation to earlier studies and theories. Concerning the first research question about what factors are important for the parents’ choice of preschool, six themes were identified: The possibility to be out in nature a lot, an enlargement of reality through traveling to different places, the competent preschool teachers, the opportunity to be physically active more frequently, social aspects such as a unique social identity and social cohesion, and finally a mix of social recommendations and disruptions that made the parents start thinking about choosing the mobile preschool in the first place. Regarding the second question about what competencies they consider their children will receive by being a part of this type of preschool these can be divided into two broad clusters: care- and cooperation-oriented reasons and competencies (such as empathy and social responsibility), and freedom- and independence-oriented reasons and competencies (such as independence, creativity, and self-confidence). The parents also referred to parent-oriented reasons. However, the commonly identified dichotomy of care and education was not present in the parents’ stories (see Rentzou 2013).

In order to obtain a more in-depth and general understanding we analyzed the results in relation to two educational policies: ESD (care and cooperation oriented) and entrepreneurship in school (freedom and independence oriented, as well as parent oriented). They are closely related to two overarching societal discourses: the sustainability discourse and the neoliberal discourse. We perceive these policies as two, sometimes conflicting, discourses.

Preparing for a Sustainable Society—Care- and Cooperation-Oriented Competencies

In interviews with civil servants about the intentions for the mobile preschools they emphasized both the social and ecological aspects of the sustainability concept as competencies they would like to promote (Gustafson et al. 2017). This is in line with research about ESD (Elliot 2013). Thus, one can ask: How do the parents’ views align with these ideals?

The parents’ stories illustrate how nature and the ecological dimension of the sustainability concept stand out as one of the most important aspects in their choice of preschool. Playing in nature is seen as promoting respect and empathy for animals and nature at large; a few parents even see it as promoting future environmental awareness, which is supported by research (Chawla and Cushing 2007; Evans et al. 2018). This view is also in line with the national curriculum for early childhood education in Sweden, which declares that all preschools should ensure that children develop respect and care for all forms of life and for the surrounding environment (The Swedish National Agency for Education 2018). However, only a few of the parents touched upon the social dimension of the sustainability concept, for example by referring to how the possibility of meeting different people can prevent prejudices. Nevertheless, social sustainability has been mentioned by those responsible at the municipality level as one of the two main ideas behind the mobile preschool (Gustafson et al. 2017). This gap between parents’ views and policy-level intentions is not surprising, since research shows that preschool practice often primarily focuses on the ecological part of the sustainability concept (Hedefalk et al. 2015).

Researchers in the field of early childhood ESD argue that it is essential to focus on caring for oneself, for others, and for the world in preschools, and that these aspects should be seen as integrated (Johansson 2009; Samuelsson 2011). In addition to having their children begin to care for nature, the parents acknowledged that the psychological and physical health of their children benefits from the children being out in nature a lot. However, the parents did not relate this to the ecological or broader social aspects of sustainability. Still, ethnographic research in a mobile preschool has shown that when playing in nature, children integrate human and nonhuman aspects through social practice (Ekman Ladru and Gustafson 2018).

Most parents see the practical aspect of learning about nature as something very positive and that primarily leads to a good knowledge of nature, as well as promoting cognitive learning. In this regard, early childhood ESD researchers have emphasized the importance of not only education “about” and “for” the environment, but also education that occurs “in” the environment (Hedefalk et al. 2015). Researchers have found that outdoor education can help children grasp mathematical concepts, for example (Fägerstam 2012).

The parents’ use of words such as “natural” and “healthy,” their uncritical view of nature as something that is purely positive, and their nostalgic references to their own childhood memories can also be analyzed in relation to research about middle-class parents’ discourses about nature and childhood (Halldén 2011; Valentine 1996). Here, childhood is seen as characterized by innocence; nature is seen as a natural and safe haven where children are shielded from “unnatural” things such as premade toys and computer games. This view of nature as something that is separate from modern life can prevent parents from recognizing the interdependence of society and nature. Nature is seen as something different that can be “used” by humans—a view that is not positive from a sustainability perspective.

In addition, the parents mentioned that being out in nature a lot promotes strong cooperation skills that lead to a strong group identity. They also said that the pedagogues in this type of preschool seem to be particularly dedicated and suited to care for their children’s needs, and appear to cooperate with the children in a good way. Good cooperation with others is a basis for sustainability competencies such as interpersonal competency and strategic competency (Wiek et al. 2011). Of course, these skills can also be used to work toward unsustainable goals, and it is somewhat unclear why the parents perceive these skills as important. What is obvious is that the parents’ stories involved cooperation among teachers and children who are inside their own “in” group and who are “like them”; the parents further compared their children with the “other” children who are not in the mobile preschool. In the worst case, this can lead to “we and them” thinking among the children. In the best case, these aspects can be seen as a first step toward cooperating with all kinds of people. Attachment theory claims that by gaining strong attachments to those close to them, children develop “basic trust,” which is a precondition for future openness toward those who are different (Collins and Read 1994; Denham et al. 2014).

Preparing for the Neoliberal Society—Freedom- and Independence-Oriented Competencies

In addition to care-oriented aspects, the parents mentioned many freedom- and independence-oriented factors. On the one hand, these factors are individual/self-focused aspects that include giving the children an outlet for inbuilt energy, allowing them to develop motor skills, and promoting traditional cognitive skills by having children learn in nature using practice-based pedagogies. All of these aspects have been mentioned in research on general outdoor education (Fägerstam 2012) as well as in research about mobile preschools specifically, for instance in the interviews with civil servants regarding mobile preschools (Gustafson et al. 2017).

However, the parents also mentioned “tough” and competition-based aspects that, interestingly, have not been acknowledged much before. These aspects include the benefits of having pedagogues that are not overly cautious, who let the children try things out, and who are not particularly risk oriented. Furthermore, the children are seen as becoming tougher, more independent, more self-confident, and ready to take on every challenge as a result of being out in nature. Creativity is also emphasized in this context. The mobile preschool is also seen as something that prevents children from becoming bored. Moving to different places all the time is seen as an advantage, and variation of experiences is in focus. These aspects are sometimes motivated more out of the parents’ own preferences for excitement rather than being child-focused. For example, the parents viewed the mobile preschool’s activities as compensating their children for the parents’ own busy work schedules that do not leave them with enough time to do certain activities with their children. At the same time, the preschool’s strong discipline was seen as something positive that placed boundaries around the creative play taking place in nature. These aspects are reminiscent of another policy orientation namely, entrepreneurial learning (Axelsson 2017). As mentioned in the introduction, entrepreneurship is mentioned implicitly in the Swedish preschool curriculum, through statements about instilling curiosity, creativity, self-confidence, and interest in children by allowing them to gain new experiences (The Swedish National Agency for Education 2018). These very individualized competencies seem to be highly valued by the parents.

Research on mobile preschools and on outdoor play in other forms of preschools, however, shows that the discourse on children’s independence is in fact very dependent upon doing things together (Ekman Ladru and Gustafson 2018; Mikkelsen and Christensen 2009). Although explorations of different places may appear to be independent play on the surface, such explorations occur in concert with other children, objects, and animals, where everything is interdependent. The children’s “independent” play is enabled through a multitude of relationships. These aspects related to intertwinement are not present in the parents’ stories.

In this context, it is interesting to note the emotional aspects mentioned by the parents. The activities in the mobile preschool are seen as activating positive emotions among the children such as happiness and joy; the parents also mentioned that the activities prevent negative emotional reactions such as irritation and being bored. In addition, the pedagogues are perceived as being optimistic and in a positive mood. In this regard, some researchers argue that the neoliberal discourse steers through emotional norms that establish which emotions are appropriate to feel and which are not—something that also influences the educational system (Duffy 2017; Ecclestone and Hayes 2008; Ideland 2016). According to this discourse, positive emotions are the only ones that are allowed, and negative emotions should be suppressed since they disturb the order of things. From this perspective, the boredom that comes from remaining in the same place can be seen as dangerous, threatening the “feverish tempo” of the neoliberal society. Research in developmental psychology, however, has shown that attachment to specific people and places among young children is essential for later independence (Collins and Read 1994; Denham et al. 2014). Furthermore, boredom can be essential for creativity (Park et al. 2019). In addition, children who do not fit into these emotional norms or who are seen as being unable to live up to the entrepreneurial norms can be excluded (Axelsson 2017; Duffy 2017; Ideland 2016). In this regard, the parents’ stories reveal that they perceive a specific type of child as best suited for the mobile preschool form.

Conclusion

Parents’ attitudes toward preschool practices are important from a pedagogical perspective, since they can influence the outcome of the learning process (Borg 2017; Hayward et al. 2015). In this article, we explored what aspects a group of Swedish parents takes into account when deciding to place their children in the mobile preschool. We also argued that these aspects can be better understood when analyzed in relation to two societal discourses: the sustainability discourse, which promotes cooperation and care for nature, society, and oneself; and the neoliberal discourse, which promotes independence, variety, and a tough and positive mindset.

Mobile preschools are being promoted as an opportunity to enhance sustainability as a broader concept including both social and ecological aspects. However, parents’ aims are dominated by the ecological and also an independence dimension. Parents’ compartmentalized and individualized view on competencies—including “tough” competencies—can be contrasted with mobile preschools’ intention to set the ground for a more integrated view of sustainability and care. Since parents’ views can influence the outcome of the learning process one could argue that these views need to be taken into account by those who are responsible for the mobile preschool.

This study contributes to the literature on school choice by illustrating that although parental choice of early childhood education and care is connected to structural aspects, such as having access to a mobile preschool in the first place, and to pedagogues’ recommendation of particularly “active” children for this type of preschool, parental choice is also intertwined with societal and educational discourses on what children need to learn and what skills they need to attain, and on how the mobile preschool provides for these needs. These findings thus bring important knowledge to early childhood educational practices about how to understand and cooperate with parents regarding their choices and preferences.

References

Axelsson, K. (2017). Entrepreneurship in a school setting: Introducing a business concept in a public context. Mälardalen University Press. Doctoral dissertation.

Biesta, G. (2015). Teaching, teacher education, and the humanities: Reconsidering education as a Geisteswissenschaft. Educational Theory. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12141.

Borg, F. (2017). Caring for people and the planet: Preschool children’s knowledge and practices of sustainability. Umeå University. Doctoral Dissertation.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brown, W. (2003). Neo-liberalism and the end of liberal democracy. Theory and Event, 7(1), 1–3.

Carrier, C. (2005). Pedagogical challenges in entrepreneurship education. In P. Kyrö & C. Carrier (Eds.), The dynamics of learning entrepreneurship in a cross-cultural university context (pp. 136–158). Tampere: University of Tampere.

Ceglowski, D. (2004). How stakeholder groups define quality in child care. Early Childhood Education Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-004-1076-6.

Chawla, L., & Cushing, D. L. (2007). Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701581539.

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1994). Cognitive representations of attachment: The structure and functions of working models. In D. Perlman & K. Bartholomew (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships. Attachment processes in adulthood (Vol. 5, pp. 53–90). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Davies, B., & Bansel, P. (2007). Neoliberalism and education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390701281751.

Denham, S. A., Bassett, H. H., Zinsser, K., & Wyatt, T. M. (2014). How preschoolers’ social-emotional learning predicts their early school success: Developing theory-promoting, competency-based assessments. Infant and Child Development. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1840.

Drever, E. (1995). Using semi-structured interviews in small-scale research. A teacher's guide. Glasgow: University of Glasgow.

Duffy, D. (2017). Get on your feet, get happy: Happiness and the affective governing of young people in the age of austerity. In P. Kelly & J. Pike (Eds.), Neo-liberalism and austerity. The moral economies of young people’s health and well-being (pp. 87–101). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ecclestone, K., & Hayes, D. (2008). The dangerous rise of therapeutic education. New York: Routledge.

Ekman Ladru, D., & Gustafson, K. (2018). ‘Yay, a downhill!’: Mobile preschool children's collective mobility practices and 'doing' space in walks in line. Journal of Pedagogy. https://doi.org/10.2478/jped-2018-0005.

Elliot, J. A. (2013). An introduction to sustainable development. New York: Routledge.

Evans, G. W., Otto, S., & Kaiser, F. G. (2018). Childhood origins of young adult environmental behavior. Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741894.

Fägerstam, E. (2012). Space and place: Perspectives on outdoor teaching and learning. Linköping University Electronic Press. Doctoral dissertation.

Gustafson, K., & van der Burgt, D. (2015). ‘Being on the move’: Time-spatial organisation and mobility in a mobile preschool. Journal of Transport Geography. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.06.023.

Gustafson, K., van der Burgt, D., & Joelsson, T. (2017). Mobila förskolan - vart är den på väg?: Rapport från en kartläggning av mobila förskolor i Sverige April 2017. Rapport (Working paper, 2017:1). Uppsala: Uppsala University.

Halldén, G. (2011). Barndomens skogar: om barn i natur och barns natur. Stockholm: Carlsson Bokförlag.

Hayes, N. (2007). The role of early childhood care and education: An anti-poverty perspective. Centre for Social and Educational Research: Technological University Dublin.

Hayward, B., Selboe, E., & Plew, E. (2015). Citizenship for a changing global climate: Learning from New Zealand and Norway. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education.. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047173415577506.

Hedefalk, M., Almqvist, J., & Östman, L. (2015). Education for sustainable development in early childhood education: A review of the research literature. Environmental Education Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.971716.

Ideland, M. (2016). The action-competent child: Responsibilization through practices and emotions in environmental education. Knowledge Cultures, 4(2), 95–112.

Johansson, E. (2009). The preschool child of today—The world citizen of tomorrow? International Journal of Early Childhood, 41(2), 79–95.

Karlsson, M., Löfdahl, A., & Pérez Prieto, H. (2013). Morality in parents’ stories of preschool choice: Narrating identity positions of good parenting. British Journal of Sociology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.714248.

Kyprianos, P. (2007). Child, family, society. The history of preschool education from its inception until our days. Athens: Gutenberg (in Greek). Cited in Konstantina Rentzou (2013). Exploring parental preferences: care or education: what do Greek parents aspire from day care centres?, Early Child Development and Care.https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.767247

Langermar, P. (2008). Kvalitativ forskningsmetod i psykologi. Stockholm: Liber.

Mikkelsen, M. R., & Christensen, P. (2009). Is children’s independent mobility really independent? A study of children’s mobility combining ethnography and GPS/mobile phone technologies. Mobilities. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100802657954.

Moran-Ellis, J., & Tisdall, E. K. M. (2019). The relevance of ‘competency’ for enhancing or limiting children’s participation: Unpicking conceptual confusion. Global Studies of Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610619860995.

Neck, H. M., & Greene, P. G. (2011). Entrepreneurship education: Knows worlds and new frontiers. Journal of Small Business Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00314.x.

Nisskaya, A. K. (2018). What modern parents think about preschool education. Russian Education & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/10609393.2018.1527165.

Park, G., Lim, B.-C., & Oh, H. (2019). Why being bored might not be a bad thing after all. Academy of Management Discoveries. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2017.0033.

Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2011). Why we should begin early with ESD: The role of early childhood education. International Journal of Early Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-011-0034-x.

Rentzou, K. (2013). Exploring parental preferences: Care or education: What do Greek parents aspire from day care centres? Early Child Development and Care. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.767247.

Rose, N. (1992). Governing the enterprising self. In P. Heelas, P. Morris, & P. M. Morris (Eds.), The values of the enterprise culture. The moral debate. New York: Routledge.

Rose, K., Vittrup, B., & Leveridge, T. (2013). Parental decision making about technology and quality in child care programs. Child & Youth Care Forum. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-013-9214-1.

Shlay, A. B. (2010). African American, White and Hispanic child care preferences: A factorial survey analysis of welfare leavers by race, ethnicity. Social Science Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.07.005.

The Swedish National Agency for Education. (2018). Curriculum for the preschool. Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik AB.

Valentine, G. (1996). Angels and devils: Moral landscapes of childhood. Environment and Planning D. https://doi.org/10.1068/d140581.

Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Örebro University.

Funding

This study was funded by The Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences (Grant No. P15-0543:1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (The Regional Ethics Review Board, Uppsala; Sweden. Dnr 2016/069) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ojala, M., Ekman Ladru, D. & Gustafson, K. Parental Reasoning on Choosing the Mobile Preschool: Enabling Sustainable Development or Adjusting to a Neoliberal Society?. Early Childhood Educ J 49, 539–551 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01083-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01083-z