Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between the temperament dimensions, home environment factors, and the two types of young children’s learning motivation. The study aimed to investigate the relative contributions of predictors and identify the predictors of young children’s intrinsic and extrinsic learning motivation in a classroom-based setting. To do this, 296 mothers of 5-year-old Korean children responded to a survey on children’s temperament and home environment. Teachers of the same children rated the children’s intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Five temperament dimensions and two home environment factors were associated with children’s motivation in class. After controlling for family socioeconomic status and children’s gender, children’s level of attentional focusing and the verity of developmental stimulus presented at home made unique contributions to their intrinsic learning motivation in class. However, children’s extrinsic motivation was not predicted by any of the children’s temperament and home environment characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context. Boulder Co: Westview Press.

Amabile, T. M., Hill, K. G., Hennessey, B. A., & Tighe, E. M. (1994). The work preference inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,66(5), 950.

Armstrong, R., & Hilton, A. (2010). Statistical analysis in microbiology: Statutes. New York: Wiley.

Baker, L., & Wigfield, A. (1999). Dimensions of children’s motivation for reading and their relations to reading activity and reading achievement. Reading Research Quarterly,34(4), 452–477.

Broussard, S. C., & Garrison, M. E. B. (2004). The relationship between classroom motivation and academic achievement in elementary-school-aged children. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal,33(2), 106–120.

Caldwell, B. M., & Bradley, R. H. (2003). Home inventory administration manual: Comprehensive edition. Little Rock: University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Carlton, M. P., & Winsler, A. (1998). Fostering intrinsic motivation in early childhood classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal,25(3), 159–166.

Chang, F., & Burns, B. M. (2005). Attention in preschoolers: Associations with effortful control and motivation. Child Development,76(1), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00842.x.

Choi, N. (2015). Development and validation of the scale on young children’s preferences for daily activities in early childhood institutes. Korean Journal of Child Education and Care,15(3), 293–310.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation in education: Reconsidered once again. Review of Educational Research,71(1), 1–27.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality,19(2), 109–134.

Derryberry, D., & Reed, M. A. (1994). Temperament and the self-organization of personality. Development and Psychopathology,6(4), 653–676.

Do, K. H. (2008). Relation among father’s child-rearing involvement, father-child communication style, children’s achievement motivation and school adjustment. Journal of Korean Home Economics Education Association,20(4), 139–155.

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation to succeed. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

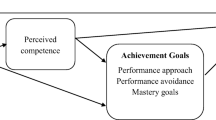

Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,82(5), 804.

Gottfried, A. E. (1990). Academic intrinsic motivation in young elementary school children. Journal of Educational Psychology,82(3), 525–538.

Gottfried, A. E., Fleming, J. S., & Gottfried, A. W. (1998). Role of cognitively stimulating home environment in children’s academic intrinsic motivation: A longitudinal study. Child Development,69(5), 1448–1460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06223.x.

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Harter, S., & Jackson, B. K. (1992). Trait vs. nontrait conceptualizations of intrinsic/extrinsic motivational orientation. Motivation and Emotion,16(3), 209–230.

Hennessey, B. A., & Zbikowski, S. (1993). Immunizing children against the negative effects of reward: A further examination of the intrinsic motivation training techniques. Creativity Research Journal,6, 297–307.

Hirvonen, R., Torppa, M., Nurmi, J. E., Eklund, K., & Ahonen, T. (2016). Early temperament and age at school entry predict task avoidance in elementary school. Learning and Individual Differences,47, 1–10.

Hokoda, A., & Fincham, F. D. (1995). Origins of children’s helpless and mastery achievement patterns in the family. Journal of Educational Psychology,87(3), 375–385.

Hughes, K., & Coplan, R. J. (2010). Exploring processes linking shyness and academic achievement in childhood. School Psychology Quarterly,25, 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022070.

Izard, C., Fine, S., Schultz, D., Mostow, A., Ackerman, B., & Youngstrom, E. (2001). Emotion knowledge as a predictor of social behavior and academic competence in children at risk. Psychological Science,12(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00304.

Jin, K. H. (2002). The effects of extrinsic rewards on children’s creativity (Master’s thesis). Seoul: Sungkyunkwan University.

Kang, H., & Park, H. (2013). The development of infants from low-income families, parenting characteristics, and daily routines. Family and Environment Research,51(6), 613–622.

Kim, Y., & Ahn, S. (2014). Types of motivation in young children: Associations with young children’s temperament and their mothers interactions. Korean Journal of Child Studies,35(4), 123–143.

Kim, K., Doh, H., & Park, S. (2010). The relationship among parenting behaviors, children’s perfectionism and achievement motivation. Korean Journal of Child Studies,31(2), 209–227.

Kim, J., & Gwak, K. J. (2007). Validity of the Korean early childhood home observation for measurement of the environment. Korean Journal of Child Studies,28(1), 115–128.

Kim, J., Jung, H., Kim, J., & Yi, S. (2012). Development of a Korean Home Environment Scale for early childhood. The Journal of Child Education,21(1), 77–92.

Kruglanski, A. W., Fishbach, A., Woolley, K., Bélanger, J. J., Chernikova, M., Molinario, E., et al. (2018). A structural model of intrinsic motivation: On the psychology of means-ends fusion. Psychological Review,125(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000095.

Lepper, M. R., Corpus, J. H., & Iyengar, S. S. (2005). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: Age differences and academic correlates. Journal of Educational Psychology,97(2), 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.184.

Lim, J., & Bae, Y. (2015). Validation study of Korean version of the Rothbart’s children’s behavior questionnaire. Korean Journal of Human Ecology,24(4), 477–497.

Locke, E. A., & Schattke, K. (2018). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Time for expansion and clarification. Motivation Science. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000116.

MacPhee, D., Prendergast, S., Albrecht, E., Walker, A. K., & Miller-Heyl, J. (2018). The child-rearing environment and children’s mastery motivation as contributors to school readiness. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology,56, 1–12.

Meij, H. T., Riksen-Walraven, J. M., & Van Lieshout, C. F. (2000). Longitudinal patterns of parental support as predictors of children’s competence motivation. Early Child Development and Care,160(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/0030443001600101.

Morgan, G. A., Harmon, R. J., & Maslin-Cole, C. A. (1990). Mastery motivation: Definition and measurement. Early Education and Development,1(5), 318–339.

Muola, J. M. (2010). A study of the relationship between academic achievement motivation and home environment among standard eight pupils. Educational Research and Reviews,5(5), 213–217.

OECD. (2017). Starting strong 2017—key OECD indicators on early childhood education and care. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2018). Education at a glance 2018: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Onatsu-Arvilommi, T., & Nurmi, J. (2000). The role of task-avoidant and task-focused behaviors in the development of reading and mathematical skills during the first school year: A cross-lagged longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology,92(3), 478–491.

Posner, M., & Rothbart, M. (2000). Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Development and Psychopathology,12(3), 427–441.

Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., Hershey, K. L., & Fisher, P. (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Development,72(5), 1394–1408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00355.

Rothbart, M. K., & Derryberry, D. (1981). Development of individual differences in temperament. Advances in developmental psychology (pp. 37–86). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rothbart, M. K., & Jones, L. B. (1998). Temperament, self-regulation, and education. School Psychology Review,27(4), 479–491.

Schiefele, U., Stutz, F., & Schaffner, E. (2016). Longitudinal relations between reading motivation and reading comprehension in the early elementary grades. Learning and Individual Differences,51, 49–58.

Schultz, G. F. (1993). Socioeconomic advantage and achievement motivation: Important mediators of academic performance in minority children in urban schools. The Urban Review,25(3), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01112109.

Statistics Korea. (2018). Household income by income level. http://kostat.go.kr.

Steinmayr, R., & Spinath, B. (2009). The importance of motivation as a predictor of school achievement. Learning and Individual Differences,19(1), 80–90.

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education,48(6), 1273–1296.

Totsika, V., & Sylva, K. (2004). The home observation for measurement of the environment revisited. Child and Adolescent Mental Health,9(1), 25–35.

Valiente, C., Swanson, J., & Lemery-Chalfant, K. (2012). Kindergartener’s temperament, classroom engagement, and student-teacher relationship: Moderation by effortful control. Social Development,21, 558–576.

Wachs, T. D. (1987). Short-term stability of aggregated and nonaggregated measures of parent behavior. Child Development,58, 796–797. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130216.

Wang, J. H. Y., & Guthrie, J. T. (2004). Modeling the effects of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, amount of reading, and past reading achievement on text comprehension between US and Chinese students. Reading Research Quarterly,39(2), 162–186.

Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of children’s motivation for reading to the amount and breadth or their reading. Journal of Educational Psychology,89(3), 420.

Ziegert, D. I., Kistner, J. A., Castro, R., & Robertson, B. (2001). Longitudinal study of young children’s responses to challenging achievement situations. Child Development,72(2), 609–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00300.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Items of Motivation Type Questionnaire (Jin 2002)

Motivation type | Items | # of items | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

Intrinsic Motivation | 1. While engaged in the activities, the child feels he/she is learning what he/she really wanted to know 2. When asked to choose one activity among others, the child thinks first which activity he/she enjoys the most before making a choice 3. The child is engaged in the activities because he/she is curious and enjoys learning 4. While engaged in the activity, the child enjoys and challenges him/herself 5. While engaged in the activity, the child prefers to figure things out independently 6. While engaged in the activity, the child likes to choose his/her own activity theme (topic) and the process independently 7. The child really enjoys the activities 8. While engaged in the activity, the child enjoys it so much that he/she forgets about everything else | 8 | .89 |

Extrinsic Motivation | 1. The child wants his/her teacher (parents) to know how good he/she is in the activity involved 2. The child wants to receive compliments through the activity 3. The child participates in the activity because others (i.e., teacher, parents) want him/her to 4. While engaged in the activity, the child is concerned about what other people (i.e., teacher, peer) think of about him or her 5. The child does not want to participate in the activity that is not recognized by others 6. The child prefers having the teacher set goals and provides the instructions for him/her to follow 7. The child does not like to participate in the activity if he/she has a choice not to participate 8. The child really wants to receive an award or present while engaged in the activity | 8 | .73 |

Appendix 2

Constructs of CBQ-Short version Scale (Rothbart et al. 2001)

Dimension | Constructs [item number of the original scale] | # of items used in the study | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

Approach | Amount of excitement and positive anticipation for expected pleasurable activities [15, 46, 58] | 3 | .59 |

High-intensity pleasure | Amount of pleasure or enjoyment related to situations involving high stimulus intensity, rate, complexity, novelty, and incongruity [4, 10, 33, 69, 78*, 88] | 6 | .67 |

Smiling laughter | Amount of positive affect in response to changes in stimulus intensity, rate, complexity, and incongruity [19*, 48*, 79, 80*] | 4 | .62 |

Activity level | Level of gross motor activity including rate and extent of locomotion [1, 12, 18*, 22, 50*, 85, 93*] | 7 | .63 |

Impulsivity | Spread of response initiation [7, 28, 36*, 43*, 51, 82*] | 6 | .62 |

Fear | Amount of negative affect, including unease, worry or nervousness related to anticipated pain or distress and/or potentially threatening situations [17, 23, 35*, 41, 63, 68*] | 6 | .77 |

Anger/Frustration | Amount of negative affect related to the interruption of ongoing tasks or goal blocking [2, 14, 30, 40, 61*, 87] | 6 | .72 |

Inhibitory control | The capacity to plan and to suppress inappropriate approach responses under instructions or in novel or uncertain situations [38, 45, 53*, 67, 73, 81] | 6 | .70 |

Attentional Focusing | Tendency to maintain attentional focus upon task-related channels [16*, 21*, 62, 71 84*, 89] | 6 | .70 |

Low-intensity pleasure | Amount of pleasure or enjoyment related to situations involving low stimulus intensity, rate, complexity, novelty, and incongruity [26, 39, 57, 65, 72, 76, 86, 94] | 8 | .62 |

Perceptual sensitivity | Amount of detection of slight, low-intensity stimuli from the external environment [5, 13, 24, 32, 47, 83*] | 6 | .71 |

Appendix 3

Items of the Korean Home Environment Scale for Infants’ and Toddlers’ Homes (Kim et al. 2012)

Dimension | Items | # of Items | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

Developmental stimulus | 1. There are more than X CD(s) or tape(s) of children’s song at home 2. There are more than X toy(s) (dolls, materials for hospital play, dramatic play, and etc.) permitting role play 3. There are more than X artwork(s) (artworks bought for decorations or done by the child) displayed at home 4. There are more than X number-construction play material(s) (blocks, puzzles, Frobel’s gift, Gabe and etc.) at home 5. There are more than X Korean alphabet learning material(s) (word cards, Korean alphabet learning videos and etc.) at home 6. There are more than X toys permitting free expressions 7. I do Korean language learning activities(s) (reading, writing, using word cards, watching Korean alphabet learning videos and etc.) together with the child | 7 | .79 |

Responsivity | 8. I try to help my child develop at his or her own level of development (I strive to provide an educational environment that suits my child’s characteristics) 9. I try to use a variety of new words to help my child develop language 10. I usually talk with my child a lot 11. I usually compliment my child a lot 12. I usually talk using easy words that match my child’s level 13. I usually compliment my child 14. I usually talk to my child with a bright and gentle voice | 7 | .78 |

Opportunities for various experiences | 15. My child is taken to the movies more than X time(s) per year 16. I visit museums or exhibitions with the child more than X time(s) per year 17. My child is taken on a family trip more than X time(s) per year 18. I do physical and outside activities with the child | 4 | .54 |

Arrangement of the daily routine | 19. My child has a regular day schedule (meal, bedtime, playtime, and walks, etc.) 20. I encourage my child to sleep at regular times 21. I set a time for my child’s TV viewing time (e.g. TV viewing time is limited within 30 min) | 3 | .66 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, N., Cho, HJ. Temperament and Home Environment Characteristics as Predictors of Young Children’s Learning Motivation. Early Childhood Educ J 48, 607–620 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01019-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01019-7