Abstract

It is now established that the consumption discount rate is determined by the growth of consumption multiplied by the elasticity of marginal utility, but distributive concerns are rarely reflected in the literature. Assuming a social welfare function with inequality aversion, we consider a consumption discount rate that can be decomposed into the growth effect and the intragenerational distribution effect. The framework is then extended to include population change and inequality in the environment as an amenity in a utility with constant elasticity of substitution. Numerical examples illustrate that distributional effects turn non-negligibly negative, that may reduce consumption discount rate by 1–3% for plausible parameters, once distribution is adjusted for both population and the environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In a cost-benefit analysis of climate change policy, benefits and costs that arise in the future are recalculated in present terms. There is a long history of discussion about this time weighting—or discounting—in the policy and academic arenas, and even more has been written since the publication of the Stern Review (Stern 2006) and related studies (e.g., Nordhaus 2008). This is because climate change policy is a typical textbook example of long-run projects, so that even a minor change in the discount rate could change bottom line net benefits, even under the presence of sound sensitivity analysis. The climate discounting literature rediscovers the well-known Ramsey formula, according to which the consumption discount rate can be decomposed into the pure rate of time preference and the product of the elasticity of marginal utility of consumption and the growth rate of consumption. Choosing the right values, if any, for each parameter or scenario has been shown to be a controversial task involving social agreement on not just facts but also values (Dasgupta 2008; Heal and Millner 2014).Footnote 1

Most of these studies assume an aggregate world consumption to derive consumption-based discount rates. However, a salient feature of climate change damage is that it has asymmetric consequences in terms of geography and income groups. Moreover, policies that attempt to address the issue, which are commonly dichotomized between mitigation and adaptation, have differentiated economic impacts on different groups. On the one hand, carbon taxes or emission permits require that emerging as well as developed nations disburse the social cost of carbon, at least in the current policy framework. On the other hand, disaster management, or more generally, adaptation strategies, usually benefit mostly lower income groups in vulnerable nations and islands. The dual practice of mitigation and adaptation would then have mixed effects on intragenerational inequality in the world. In the absence of those measures, it is possible that aggregate consumption continues to grow while income distribution becomes more unbalanced. Put differently, the debate about the temporal substitution of well-being should also take account of how aggregate consumption is divided within each generation (e.g., López 2005).Footnote 2

Thus, a relevant research question is what the discount rate in an increasingly unequal (or equal) world should look like.Footnote 3 The importance of equity weighting in climate change discounting has been highlighted already in a welfare-theoretic approach, including Azar and Sterner (1996), Fankhauser et al. (1997), Azar (1999), Pearce (2003), and Anthoff and Tol (2010). Studies considering non-consumption discounting has also become vast. Weikard and Zhu (2005) consider dual discounting for consumption and the environment; Hoel and Sterner (2007) study relative scarcity price of the environment; Kaplow and Weisbach (2011) separate the nexus from consumption to utility and then to social welfare; Traeger (2011a, b) incorporates limited substitutability of the environment. Yamaguchi (2013) considers consumption discount rates of the rich and poor when there are both consumption goods and the environment; however, imagining differentiated discount rates for different income groups yields practical difficulties. We instead focus on a single discount rate with an aggregate consumption numeraire and investigate the consequences of changing intragenerational distribution of consumption.

In a recent related literature, Emmerling (2018) and Anthoff and Emmerling (2016) carefully include intragenerational equity in discounting and social cost of carbon, and most notably, investigate their link with the Atkinson measure of inequality. Emmerling et al. (2017) propose focusing on the consumption discounting of the median-income household. Gollier (2015), noting the similarity between inequality and uncertainty, separates initial consumption level inequality and growth rate inequality. He shows an intuitive result by which the expectation of economic convergence raises the discount rate when relative prudence is larger than unity. Fleurbaey and Zuber (2015a), also addressing both inequality and uncertainty, find that extremal returns and the position of the worst-off matter. In an emerging literature of solvable model of climate change and social cost of carbon, Rezai and van der Ploeg (2016) test both one and two for the parameter of intergenerational inequality aversion.

In our study, we imagine an instantaneous distribution mechanism that determines mapping of aggregate consumption to individual consumption in each period, given the aggregate consumption growth. Assuming constant relative inequality and risk aversion, we consider the consumption discount rate that is decomposed into the aggregate consumption growth effect and the effect of intragenerational distribution change. Furthermore, we include in the framework the issues of population change in order to determine the social weights of each group, and heterogeneous “distribution” in the environmental quality. Application of the model to numerical examples of climate change reveals that the distribution effect on the consumption discount rate, especially including population or the environment, is not negligible.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the basic framework, and the consumption discount rate is decomposed into growth and distribution effects. Section 3 includes population as one factor affecting the changing value share of groups. Section 4 introduces unequal benefits of environmental amenity in the basic model. Section 5 illustrates the foregoing by numerical examples used in the RICE (Regional dynamic Integrated model of Climate and the Economy) model. Section 6 provides some discussion and directions for possible future works.

2 Model Description

2.1 Basic Model

The starting point of our discussion is a Bergson–Samuelson social welfare function (Drèze and Stern 1987, 1990; Johansson-Stenman 2000, 2005), which is explicit about income distribution within each generation. We consider discrete, individual groups labeled \(i =1, 2, \ldots , N\). One of the simplest expressions is:

where \(u(C_i(t))\) is the utility derived from consumption of group i at time t, which might be a country or a person within a group. In addition, we assume that, if it represents a group of people, \(i =1, 2, \ldots , N\) is of the same size or population. The utility discount rate, or the pure rate of time preference, is denoted by \(\delta \).Footnote 4 Furthermore, we assume a constant inequality aversion in mapping individual utility to social welfare, \(V: {\mathbb {R}}^N \rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}\). That is,

where \(\sigma \le 1\) signifies inequality aversion among different i’s. The case of \(\sigma =0\) makes a Benthamite utilitarian social welfare function. To focus on the distributional considerations, we define an intragenerational distribution mechanism \(\Delta (t): C(t) \rightarrow (C_1(t), C_2(t), \ldots , C_N(t))\), where C(t) is the aggregate consumption at t. In each period, the global aggregate consumption C(t) is given, which then is to be divided among the groups, according to the mechanism \(\Delta (t)\). More specifically, in each period, the mechanism \(\Delta (t)\) is determined so that

where \(\alpha _i(t)\) for \(i =1, 2, \ldots , N\) is the share of consumption of group i at t, and \(\sum _{i=1}^N \alpha _i(t)=1\) for all t.

Now we imagine one dollar to be invested at time 0 in a marginal project, which should yield a return of \(e^{r(t)t}\) dollars at time t under a socially efficient discount rate, r(t) (e.g., Gollier 2007).Footnote 5 Converting to the welfare numeraire, the initial investment of \(\partial W(0)/\partial C(0)\) would amount to \(e^{r(t)t} \partial W(0)/\partial C(t)\) in the future, t. This implies that it should be written, provided the social discount rate r(t) is efficient, as

It is clear from the above expression that the social consumption discount rate represents the (negative of) change rate of the shadow price of aggregate consumption from 0 to t. Expanding the right-hand side (RHS) of (4) yields, using (3),

where

can be called the (initial) value share of group i at 0. This is reminiscent of the value share of the environment in Hoel and Sterner (2007), but here, we consider the value share of consumption of different groups of individuals. As can be observed, the value share is inclusive of not only the share of consumption (\(\alpha \)), but also its marginal utility (\(u_c\)) and the utility’s contribution to social welfare (\(u^{-\sigma }\)).

2.2 CRRA Utility

A standard formulation of the utility function, especially in debates on climate change, is of the constant relative risk aversion (CRRA) type. Following the literature, we suppose \(u(C_i(t)) = C_i(t)^{1-\eta }/(1-\eta )\), with \(\eta >1\) being the elasticity of the marginal utility of consumption. Plugging this specified utility into (5), by ordinary calculation, we obtain

since aggregate consumption has no suffix and thus, can be inserted prior to the summation. Then, we obtain

Proposition 1

In the case of a CRRA utility function when social groups differ in consumption, the consumption discount rate can be decomposed as

where the initial value share of i is

As indicated, this states that now the consumption discount rate can be decomposed into the aggregate consumption growth effect, sometimes referred to as the wealth effect, and the changing distribution effect of consumption within each generation, apart from the pure rate of time preference.

The distribution effect revealed in the last term in (7) is negative (positive) when \(\sum _{i=1}^N \phi _i(0) [\frac{\alpha _i(t)}{\alpha _i(0)}]^{(1-\sigma )(1-\eta )}\) is larger (smaller) than unity. The distribution effect disappears if \(\sum _{i=1}^N \alpha _i(t)^{(1-\sigma )(1-\eta )} = \sum _{i=1}^N \alpha _i(0)^{(1-\sigma )(1-\eta )}\). This is clearly satisfied not only when \(\alpha _i(t)/\alpha _i(0)=1\) for all \(i=1, \ldots , N\), that is, the distribution mechanism is exactly the same between two periods under study, but also when the distribution is the same but the positions of i’s are partially or totally interchanged with each other. The latter case can be paraphrased by the case in which re-ordering all i’s by the level of consumption at t and relabeling them would yield exactly the same distribution at 0. In other words, if there is even the slightest change in the within-generation distribution mechanism, then the distribution term becomes non-zero, be the change “worse” or “better.” This is because when somebody’s consumption share becomes higher, somebody else’s is bound to be lower. In addition, note that even if the aggregate consumption does not change (i.e., \(C(t)=C(0)\)), the distribution effect is generally non-zero, so that \(r(t) \ne \delta \).

Regarding the aggregate consumption effect in (7), we have an additional term \(\sigma (1-\eta )\), besides the usual relative risk aversion, \(\eta \). This is a direct result of our social welfare function (2), in which inequality aversion parameter \(\sigma \) is attached to utility. As it seems, \(\eta \) and \(\sigma \) have precisely the same effect in (7), which is highlighted by the fact that \(\eta + \sigma (1-\eta ) = 1-(1-\sigma )(1-\eta )\). Thus, in this specific sense, they are mathematically redundant; however, in terms of ethical interpretation, they are not: \(\eta \) descriptively represents the relative risk aversion of each group or individual, i, whereas the product of \(\sigma \) and \(1-\eta \) is a normative value for intergenerational inequality aversion, and thus, is required to be determined on ethical grounds (Kaplow 2010).

If we set \(\sigma =0\), the aggregate growth effect takes the familiar form, \(\eta g\), where g is the average growth rate of aggregated consumption, and yet, the distribution remains in the form \(\frac{1}{t} \ln \sum _{i=1}^N \phi _i(0) [ \frac{\alpha _i(t)}{\alpha _i(0)}]^{(1-\eta )}\), because individuals are risk averse. This is because individual utility is still risk averse; what matters is that we have disaggregated the world into more than one individual. Introducing intragenerational heterogeneity gives rise to the distributional effect, even under utilitarian social welfare.

Given that \(\eta >1\), the inequality aversion parameter \(\sigma \) has two consequences if it is smaller than unity: the smaller \(\sigma \) is, the larger the growth effect becomes because of the intergenerational inequality aversion when the economy is growing, and the larger the distribution effect becomes. The latter occurs because the term puts a heavy weight on those whose consumption shares are decreasing. As a result, the overall effect on r(t) is ambiguous. The following simple examples facilitate understanding.

Example 1

(No growth with increasing inequality) Suppose that the economy is made up of two individuals, \(i=1,2\). The ethical parameters are set so that \((1-\sigma )(1-\eta )=-1\) (a plausible example is \(\eta =1.5\) and \(\sigma =-1\), etc.). Assume that the economy is completely stagnant from 0 to t; this zero-sum setting implies that there is no possibility of Pareto improvement. Assume also that the distribution mechanism is expected to “worsen” from \(\Delta (0): 1 \rightarrow (1/2,1/2)\) at 0 to \(\Delta (t): 1 \rightarrow (2/3,1/3)\) at t. It follows that \(\alpha _1(0)=\alpha _2(0)=1/2, \alpha _1(t)=2/3\) and \(\alpha _2(t)=1/3\), and \(\phi _1(0)=\phi _2(0)=1/2\). There is no growth effect as such, but the distribution effect isFootnote 6

In this example, the original state is perfectly equal, so that any change in distribution would result in a lower discount rate, other things being unchanged.

If we put more emphasis on inequality aversion by setting, say, \((1-\sigma )(1-\eta )=-2\), this becomes

leading to an even lower discount rate.

Example 2

(No growth toward equality) A similar example with four individuals with \(\Delta (0): 1 \rightarrow (1/2,1/6,1/6,1/6)\) at 0 to \(\Delta (t): 1 \rightarrow (1/4,1/4,1/4,1/4)\) at t indicates that the distribution effect becomes

This last example shows that a case is made for a higher consumption discount rate when there is no growth toward more equal (perfectly equal in this context) distribution.

Example 3

(Positive growth vs. unequal distribution) Suppose that the economy is expected to grow at a constant rate during the period [0, t] (e.g., due to an economic stimulus package), but also, that this policy is bound to make distribution more unequal (e.g., due to the policy being targeted at a specific income group). Now, in what circumstances does this distributional change nullify the growth effect in determining the consumption discount rate? Put differently, how much growth does this economy need to compensate the distributional effect on the consumption discount rate? To observe this, both effects cancel each other out if the following happens to hold

from (7). In Example 1, growth of 5.89% \((=0.1178/2)\) during the whole period is required to cancel out the distribution effect when \(1- (1-\sigma )(1-\eta )=2\). Even faster growth of 11.36% (=0.3409/3) would be required when inequality aversion is such that \(1- (1-\sigma )(1-\eta )=3\). In Example 2, negative growth of \(-11.16\% \, (=-0.2231/2)\) suffices to invalidate the distribution effect.

3 Population Change

Up until this point, we have assumed that each group i is of the same size, or almost equivalently, that i refers to an individual. Although rarely discussed in the discounting debate,Footnote 7 in application, we often want to compare groups of varied sizes, implying that distribution-conscious discounting should embody population in their weighting factors.Footnote 8

Let the objective function (2) slightly change to

where \(C_i\) and \(L_i\) are consumption and population, respectively, of “country” \(i=1, \ldots , N\). Under the same utility function of the CRRA type, it is straightforward to show the following proposition.

Proposition 2

In the case of a CRRA utility function when social groups differ in consumption and population, the consumption discount rate can be decomposed as

where the initial value share of i is defined by

The growth effect of aggregate consumption is preserved from Proposition 1. By contrast, the value share of a group in social welfare is altered slightly to include population change. In addition, the distribution effect is now inclusive of population change of individual groups. We observe that with a given distribution mechanism, increasing population of any group i implies a lower discount rate, assuming normal values for inequality and risk aversion parameters. This aspect is more explicitly noted in the following special case.

Corollary 2

If the annualized population growth rate of group i is n for all i, then the consumption discount rate with different population groups is

The annualized growth effect in this case changes to the growth rate of aggregate consumption per capita across all the groups, weighted by risk and inequality aversion, whereas the distribution effect is of the same form as Proposition 1. It is also easy to check from (13) that, other things being equal, the higher n is, the lower \({\bar{r}}(t)\) becomes.

4 Unequally Distributed Environmental Amenity

The current literature on the economics of climate change focuses on how aggregate consumption changes along the path. As long as climate change ultimately affects final consumption, this approach should be sufficient. It could be the case, however, that a change in the environment directly affects well-being, rather than by way of the consumption–utility nexus. This typically represents circumstances in which the environment has an amenity value (e.g., Krautkraemer 1985) or pollution causes disutility (e.g., Xepapadeas 2005). Since the substitution possibility between consumption and the environment is considered limited, it is shown by Hoel and Sterner (2007) that consumption discount rates are likely to become even lower in a growing economy with deteriorating environment. Thus, in the current context, it is worth exploring a case in which there is intragenerational equity in terms of the environment as an amenity, as well as intragenerational equity in consumption. To consider such a case, the objective function (2) is now modified to

where \(E_i (\tau )\) stands for the benefit i receives from the global environmental quality at \(\tau \), \(E(\tau )\), such as the atmosphere as a carbon sink. When the environmental quality is a pure public good, we assume \(E_i(\tau )=E(\tau )\) for all i. In general, suppose that the environmental quality is not a pure public good, and its benefit is received unevenly between agents according to the enhanced distribution mechanism \({\hat{\Delta }}(t): X(t) \rightarrow (x_1(t), x_2(t), \ldots , x_N(t))\), where \(X(t)=[C(t),E(t)]^{-1}\) and \(x_i(t)=[C_i(t),E_i(t)]^{-1}\) are the vectors of aggregate and individual consumption and environmental quality.

Unless the utility function is separable between consumption and the environment, changing marginal utility involves the relative abundance of the environment, so that a discount rate should include its quantity even if the numeraire is consumption. Following Hoel and Sterner (2007), consider a constant elasticity of substitution (CES), \(0<\epsilon \le 1\), between consumption and the environment:

where \(0<\beta <1\) is a relative weight factor. Define \(\gamma _i(t)=E_i(t)/E(t)\) as the portion i benefits from the environment where \(\sum _i^N \gamma _i(t)=1\). Simple calculation leads to the following proposition.

Proposition 3

In the case of a CES-CRRA utility function that depends on consumption and the environment, when social groups differ in consumption, the consumption discount rate can be written as

To separate the last term in (16) into the pure environmental effect and distributional concerns, we consider two sub-classes in the following.

Example 1

(Cobb–Douglas preference) The limiting case in which \(\epsilon \rightarrow 1\) in the above CES utility corresponds to the Cobb–Douglas preference regarding consumption and the environment. That is, we obtain

Then, the consumption discount rate is reduced to

This variant is decomposed into the growth, environmental growth, and distribution effects (second, third, and fourth terms in the RHS of (18), respectively). The growth effect is weakened precisely for the portion of consumption that succumbs to the environment in preferences. As long as the environmental quality is improving, the environmental growth effect pushes up the discount rate by its growth rate multiplied by \(\beta (\eta -1)(1-\sigma )\) if \(\sigma <1\). In other words, a better (worse) environmental amenity, to a certain extent, attenuates (amplifies) the effect of the worsening growth or distribution in consumption. This is due to the important limitations we pose in this Example: that consumption goods and the environmental amenity are perfectly substitutable (\(\epsilon \rightarrow 1\)). In addition, note that the distribution effect now reflects how the environment benefits each group. Observe also that this distribution effect differs from the last term in (7) in Proposition 1, unless \(\alpha _i(\tau )=\gamma _i(\tau )\)\(\forall i\) for \(\tau =0,t\), or unless \(\beta = 0\).

Example 2

(Inequality in the environmental amenity can be approximated by consumption inequality) Another way to decouple the environmental effect from the overall discounting is to suppose that the distribution of environmental quality happens to be proportional to distribution in consumption, namely, \(\alpha _i(\tau )=\gamma _i(\tau )\) for \(\tau =0,t\). In fact, Nordhaus and Boyer (2000) suggest that 2.5-degree temperature warming results in damage equivalent to 0.5% of national gross domestic product, implying that environmental damage can be proportional to consumption. Of course, this is just a first approximation and it should be considered that the most vulnerable groups are likely to be damaged disproportionately.Footnote 9 Then, (16) in Proposition 3 is approximately simplified to

Observe that the third term on the RHS of (23) represents the changing scarcity of the environment relative to general consumption goods and how much they are valued in the economy. Evidently, the larger \(\beta \) is, the larger this environmental effect becomes. The sign of the environmental effect depends on the choice of parameters, as well as on whether the environment improves relative to the increase in consumption goods. If \(1-(1-\sigma )(1-\eta )>1/\epsilon \) holds, then inequality aversion both at societal and individual levels and substitutability are all high, and thus, an improving (degrading) environmental amenity translates into a higher (lower) consumption discount rate, other things being equal.Footnote 10 Otherwise, the substitutability between consumption and the environment is so poor that inequality aversion does not compensate for it, and together, they lower the discount rate in an improving environment.

An obvious lesson from (23) is that, if the environmental amenity is unevenly distributed in the same manner as general consumption is, the distribution effect in discounting does not change, as is clear from the last term. However, imagine the rural poor with low consumption and high endowment of natural environment.Footnote 11 Since this type of the poor likely enjoy the natural environment, it could be the case that consumption distribution is inversely related to environmental distribution. More generally, there is some evidence that the environmental amenity is even more unequally distributed between developed and developing countries, particularly regarding climate change. Thus, in Sect. 5, we also show an alternative case where environmental distribution is equalized among regions, for want of a sound theory or data of environmental distribution.

4.1 Population- and Environment-Adjusted Discounting

Finally, we consider population adjusted social welfare function that includes consumption and the environment:

where we have assumed that the environmental amenity is a public good within each region, that is, each individual in a given nation consumes exactly the same amount of amenity. Then, a counterpart to (16) isFootnote 12

5 An Illustration

To obtain a sense of the order of the magnitude of the effect of distribution on discounting, we expound numerical examples in this section. In this section, we rescale individual utility by assuming

or

where minimum subsistence consumption and the environment are denoted by \({\underline{C}}\) and \({\underline{E}}\), so that we can take the full rage of \(\eta \) and \(\sigma \), since the utility is now non-negative. Although our central motivation for this specification is technical, this CRRA utility with minimum subsistence level has a good pedigree in the literature.Footnote 13

The basic parameters to be employed for our illustrative purposes are shown in Table 1. For data, we use the “no controls (baseline)” results of the regionally disaggregated RICE model of Nordhaus and Boyer (2000), which divides the world into 12 regions.Footnote 14 More specifically, we employ the already calibrated regional consumption data divided by world consumption as regional shares of consumption.

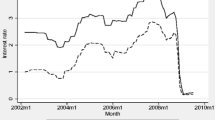

Figure 1 shows the consumption discount rates with distributional effects without (left panel) or with (right panel) population weights, corresponding to Propositions 1 and 2. Note that consumption discount rate comes largely from aggregate consumption growth effect, represented by the dotted line. Since it is projected in RICE that world consumption growth gradually declines, the growth effect also weakens over time. The distribution effect, represented by the dashed line, is relatively small and crawls around 0 in centuries from now. The latter is in part due to the fact that large emerging economies boost their share of aggregate consumption, while the developed world (the US, the EU, and Japan) decrease their share steeply, so that the overall distribution improves. In particular, in the latter half of the current century, Africa continues to increase its share. As the breakdown of world aggregate consumption does not change dramatically in approximately 1 century from now, it is not surprising then that the distribution effect is also expected to be negligible.

The distribution effect, however, becomes larger when each region is weighted with their population, as is seen in the right panel of Fig. 1. Distribution in consumption actually moderately improves, in the sense that densely populated developing regions increase their share of aggregate consumption. Consequently, consumption discount rate is raised by < 2%.

Decomposition of a consumption discount rate into growth and intragenerational distribution effects of consumption and the environment, when the environmental distribution matches consumption distribution (the left panel), or when the environmental distribution is equalized among the 12 regions under study (the right panel)

Decomposition of a consumption discount rate into growth and population-adjusted intragenerational distribution effects of consumption and the environment, when the environmental distribution matches consumption distribution (the left panel), or when the environmental distribution is equalized among the 12 regions under study (the right panel)

Figure 2 assumes that utility now depends on both consumption and the environment, without population weighting. For want of sound theory or data on how environmental amenity is distributed in the world, in the left panel it is assumed that inequality in the environmental amenity can be approximated by consumption inequality (Example 2 in Sect. 4), whereas in the right panel it is assumed that the proportions of environmental amenity a region receives are equal across regions in the world, regardless of the population, so that \(\gamma _i=1/12 \forall i\) for [0, t] in our example.Footnote 15 In addition, suppose that the global source of environmental amenity diminishes by 5% each decade, that is, \(E(t)/C(t)=0.95*E(t-1)/C(t-1)\). As a result, again, the consumption discount rate consists largely of the (combined) growth effect, with the distribution effect being minimal.

In Fig. 3, however, it is apparent that considering both the environment and population weighting changes the big picture (see (23)). In particular, the distribution effect becomes negative, being at the order of − 3 to − 1%, which decreases the consumption discount rate.Footnote 16

In summary, the seemingly negligible distribution effect turns positive when population is taken into account, because distribution improves as populous developing nations boost their consumption levels. However, once the distribution in the deteriorating environment enters the formula, the distribution effect is likely to be negative. This suggests that “improvement (worsening)” in distribution may be misleading in the absence of population and environmental concerns.

6 Concluding Remarks

In this study, we showed disaggregation of distributional components from the pure growth effect in consumption discount rates, when groups of agents in the Ramsey model are heterogeneous. In so doing, we highlighted the role of population in social weights of different groups. In addition, if environmental amenity is indeed worth highlighting in the determination of discounting and relative prices, as pointed out by Hoel and Sterner (2007) and Sterner and Persson (2008), then the “distribution” of environmental amenity around the globe should also be incorporated. Our numerical exercise suggests that the order of the magnitude of distribution effects is not overwhelming, but is still non-negligible. It is worthwhile noting that, in particular, the positive distribution effect turns negative when incorporating population and the environment.

We did not address an important aspect of long-term cost-benefit analysis, namely, uncertainty. The effects of uncertainty on discount rates have already been well treated in the literature, in particular, by Emmerling (2018) and Gollier (2012) in the current context. A possible extension of our model in this regard is to consider uncertainty in population. For example, a geometric Brownian motion of future population,

would yield an interesting modification of (11).

It is also important to note that the current approach cannot tell a “better” from a “worse” distribution change, regardless of how they are defined. In other words, the exogenous distribution effect in our model captures only changing distribution, regardless of the direction in which the distributional trend is heading; our motivation is that the current distribution can be set as a benchmark, from which future distribution deviates to an unequal world. An obvious challenge for a better calibration is to obtain empirical data on how environmental amenity is unequally distributed.

In addition, care should be taken which level of inequality we would like to address. As is stated often, international income disparities are increasingly replaced by domestic disparities, while the gap between developed and less developed nations is being narrowed (Milanovic 2016), which is exactly why some of the latter nations are referred to as emerging nations. On the other hand, Milanovic (2010) argues that Asian and European countries are relatively homogeneous within their national borders, but there are wide variations in consumption levels of different countries. Our discussion is more applicable to the latter situation, while it is easy to extend to more multi-layered inequality.

Notes

Empirical evidence is still mixed, but Milanovic (2016) finds that emerging “middle class” in Asian countries may have flattened global income distribution.

Although we do not delve into the pure rate of time preference, recent evidence abounds. Galor and Özak (2016) show that geographic and climatic factors may have determined preferences. Falk et al. (2018) demonstrate that time preferences are heterogeneous both across and within countries. Yamaguchi (2018) discusses the role of the pure rate of time preference in sustainability assessments.

We assume that the distribution is not changed by the project under evaluation (Gollier 2015). Even a small project in which a small amount of money is transferred from a poor person to a rich person can change marginal social welfare. This point is raised by a reviewer as a shortcoming of the current framework, which should be addressed in future research.

An exception is Fleurbaey and Zuber (2015b).

For example, in a recent survey distributed to over 200 experts, Drupp et al. (2018b) inquire, among others, recommended value of the “[g]rowth rate of real per-capita consumption”. Respondents are, in effect, implicitly asked to answer the composite growth rate of aggregate consumption and population.

In addition, it should be noted that environmental disamenity, which we consider here, is different from environmental damage, which can be incorporated as a negative factor in consumption.

The combined effect of \(\eta \) and \(\epsilon \) is due to Hoel and Sterner (2007).

This discussion was provided by a reviewer.

Alternatively, if the environment within each region is a private good, the social welfare function becomes

$$\begin{aligned} {\tilde{W}}_2(0)= \int _0^\infty \frac{1}{1-\sigma } \sum _{i=1}^N L_i(\tau ) \Biggl [ u \left( \frac{C_i (\tau )}{L_i(\tau )}, \frac{E_i (\tau )}{L_i(\tau )} \right) \Biggr ]^{1-\sigma } e^{- \delta \tau } d \tau , \end{aligned}$$(23)which alters the consumption discount rate slightly to

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} {\tilde{r}}_2(t)&= \delta -\frac{1}{t} \ln \left( \frac{C(t)}{C(0)} \right) ^{(1-\sigma )(1-\eta )-1} \\&\quad -\,\frac{1}{t} \ln \frac{\sum _{i=1}^N L_i(t) \left( 1 +\frac{\beta }{1-\beta } \bigl [ \frac{\gamma _i(t) E(t)}{\alpha _i(t) C(t)} \bigr ]^{1-\frac{1}{\epsilon }} \right) ^{\frac{\epsilon (1-\sigma )(1-\eta )}{\epsilon -1}-1} \left( \frac{\alpha _i(t)}{L_i(t)} \right) ^{(1-\sigma )(1-\eta )}}{\sum _{i=1}^N L_i(0) \left( 1+\frac{\beta }{1-\beta } \bigl [ \frac{\gamma _i(0) E(0)}{\alpha _i(0) C(0)} \bigr ]^{1-\frac{1}{\epsilon }} \right) ^{\frac{\epsilon (1-\sigma )(1-\eta )}{\epsilon -1}-1} \left( \frac{\alpha _i(0)}{L_i(0)} \right) ^{(1-\sigma )(1-\eta )}}. \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(24)They are the US, the EU, Japan, Russia, Eurasia, China, India, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, other high-income countries, and other.

Thus, we imagine that the “mass” of amenity can be aggregated across countries, amounting to E, but that within each region, amenity represents public goods.

When the environment within each country is a pure private good (see (22)), which is not very likely, the distribution effect becomes moderate again.

References

Anthoff D, Emmerling J (2016) Inequality and the social cost of carbon. CESifo Working Paper No. 5989

Anthoff D, Tol RSJ (2010) On international equity weights and national decision making on climate change. J Environ Econ Manag 60:14–20

Azar C (1999) Weight factors in cost-benefit analysis of climate change. Environ Resour Econ 13:249–268

Azar C, Sterner T (1996) Discounting and distributional considerations in the context of global warming. Ecol Econ 19:169–184

Baumgärtner S, Drupp MA, Meya JN, Munz JM, Quaas MF (2017a) Income inequality and willingness to pay for environmental public goods. J Environ Econ Manag 85:35–61

Baumgärtner S, Drupp MA, Quaas MF (2017b) Subsistence, substitutability and sustainability in consumption. Environ Resour Econ 67(1):47–66

Dasgupta P (2008) Discounting climate change. J Risk Uncertain 37:141–169

Drèze JP, Stern NH (1987) The theory of cost-benefit analysis. In: Auerbach AJ, Feldstein M (eds) Handbook of public economics, vol 2. Elsevier, North-Holland, pp 909–989

Drèze J, Stern N (1990) Policy reform, shadow prices and market prices. J Pub Econ 42:1–45

Drupp MA (2018) Limits to substitution between ecosystem services and manufactured goods and implications for social discounting. Environ Resour Econ 69(1):135–158

Drupp MA, Meya JN, Baumgärtner S, Quaas MF (2018a) Economic inequality and the value of nature. Ecol Econ 150:340–345

Drupp M, Freeman M, Groom B, Nesje F (2018b) Discounting disentangled: an expert survey on the determinants of the long-term social discount rate. Am Econ J Econ Policy (forthcoming). https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20160240

Emmerling J (2018) Discounting and intragenerational equity. Environ Dev Econ 23(1):19–36

Emmerling J, Groom B, Wettingfeld T (2017) Discounting and the representative median agent. Econ Lett 161:78–81

Falk A, Becker A, Dohmen T, Enke B, Huffman D, Sunde U (2018) Global evidence on economic preferences. Q J Econ (forthcoming). https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy013

Fankhauser S, Tol RS, Pearce DW (1997) The aggregation of climate change damages: a welfare theoretic approach. Environ Resour Econ 10:249–266

Fleurbaey M, Zuber S (2015a) Discounting, risk and inequality: a general approach. J Pub Econ 128:34–49

Fleurbaey M, Zuber S (2015b) Discounting, beyond utilitarianism. Econ Open Access Open Assess E J 9(2015–12):152

Galor O, Özak Ö (2016) The agricultural origins of time preference. Am Econ Rev 106(10):3064–3103

Gollier C (2007) The consumption-based determinants of the term structure of discount rates. Math Financ Econ 1(2):81–101

Gollier C (2012) Pricing the planet’s future: the economics of discounting in an uncertain world. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Gollier C (2015) Discounting, inequality and economic convergence. J Environ Econ Manag 69:53–61

Gollier C (2016) Gamma discounters are short-termist. J Pub Econ 142:83–90

Gollier C, Weitzman ML (2010) How should the distant future be discounted when discount rates are uncertain? Econ Lett 107:350–353

Heal GM, Millner A (2014) Agreeing to disagree on climate policy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(10):3695–3698

Hoel M, Sterner T (2007) Discounting and relative prices. Clim Change 84:265–280

Johansson-Stenman O (2000) On the value of life in rich and poor countries and distributional weights beyond utilitarianism. Environ Resour Econ 17:299–310

Johansson-Stenman O (2005) Distributional weights in cost-benefit analysis—Should we forget about them? Land Econ 81(3):337–352

Kaplow L (2010) Concavity of utility, concavity of welfare, and redistribution of income. Int Tax Pub Finance 17:2542

Kaplow L, Weisbach D (2011) Discount rates, social judgments, individuals’ risk preferences and uncertainty. J Risk Uncertain 42:125–143

Krautkraemer JA (1985) Optimal growth, resource amenities and the preservation of natural environments. Rev Econ Stud 52(1):153–169

López R (2005) Intragenerational versus intergenerational equity. In: Simpson RD, Toman MA, Ayres RU (eds) Scarcity and growth revisited. RFF Press, Washington

Milanovic B (2010) The haves and the have-nots: a brief and idiosyncratic history of global inequality. Basic Books, New York

Milanovic B (2016) Global inequality: a new approach for the age of globalization. Harvard University Press, Harvard

Nordhaus W (2008) A question of balance. Yale University Press, New Haven

Nordhaus WD, Boyer J (2000) Warming the world: economic models of global warming. MIT Press, Cambridge

Pearce D (2003) The social cost of carbon and its policy implications. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 19:362–384

Rezai A, van der Ploeg F (2016) Intergenerational inequality aversion, growth, and the role of damages: Occam’s rule for the global carbon tax. J Assoc Environ Resour Econ 3(2):493–522

Stern NH (2006) The Stern review of the economics of climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Sterner T, Persson UM (2008) An even sterner review: introducing relative prices into the discounting debate. Rev Environ Econ Policy 2:61–76

Traeger CP (2011a) Sustainability, limited substitutability, and non-constant social discount rates. J Environ Econ Manag 62:215–228

Traeger CP (2011b) Discounting and confidence, CUDARE DP

Weikard H-P, Zhu X (2005) Discounting and environmental quality: When should dual rates be used? Econ Model 22:868–878

Xepapadeas A (2005) Economic growth and the environment. In: Handbook of environmental economics vol. 3, pp 1219–1271

Yamaguchi R (2013) Discounting, distribution and disaggregation: discount rates for the rich and the poor with climate as a source of utility. Scott J Polit Econ 60:440–459

Yamaguchi R (2018) Wealth and population growth under dynamic average utilitarianism. Environ Dev Econ 23(1):1–18

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for fruitful conversations on discounting with Hiroaki Sakamoto over the course of the years. I would also like to thank two anonymous referees who provided very constructive comments. Evangelos Dioikitopoulos, Moritz Drupp, Francesco Ricci, Thomas Sterner (Co-Editor), and other participants of 2016 International Energy Workshop (IEW) in Cork, and the 23rd annual Conference of the European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists (EAERE) in Athens in 2017, are also acknowledged. All the remaining errors are due to the author. This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Nos. JP16K16237 and JP26000001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamaguchi, R. Intergenerational Discounting with Intragenerational Inequality in Consumption and the Environment. Environ Resource Econ 73, 957–972 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-018-0282-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-018-0282-4