Abstract

Selecting appropriate payment vehicles is critical for the perceived consequentiality and incentive compatibility of stated preferences surveys. We analyze the performance of three different payment vehicles in a Malaysian case of valuing wetland conservation. Two are well-known: voluntary donations and income taxes. The third is new: reductions in government subsidies for daily consumer goods. Using donations is common, but this payment vehicle is prone to issues of free-riding. An income tax usually has favorable properties and is commonly used in environmental valuation. However, in Malaysia as well as in many other low- to middle-income economies, large proportions of people do not pay income taxes, putting the validity of this payment vehicle into question. Instead, citizens in Malaysia and many other countries benefit from subsidies for a range of consumer goods. We find that price sensitivity is higher and the unexplained variance smaller when using subsidies rather than donations or income taxes. Importantly, this approach translates into completely different conclusions concerning policy advice. Our results suggest that in developing countries, using reduced subsidies as a payment vehicle may have favorable properties in terms of improved payment consequentiality compared to alternative payment vehicles, thus enhancing the external validity of stated preference surveys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For simplicity, we assume that our respondents perceive the elicitation as policy consequential, or at least that the perceptions of policy consequentiality do not differ across payment vehicle treatments.

Controlled goods were declared in Malaysian law under the Control of Supplies Act 1961. The list of controlled goods can be retrieved from the official website of the Ministry of Domestic Trade, Co-operatives, and Consumerism Malaysia (http://www.kpdnkk.gov.my/index.php/en/list-of-controlled-goods/28-pengguna/194-).

The data collection was undertaken with the help of trained research assistants under the instruction of the lead author. The assistants were instructed to randomly assign respondents to payment vehicle treatments. However, in the initial phase of the data collection, a couple of assistants misunderstood this instruction, which unfortunately led them to assign only two of the treatments. Despite the fact that this mistake was quickly identified and corrected, it did cause a small imbalance in the sub-samples, as is evident from Table 2.

We initially estimated separate models, but we found the attribute parameter estimates to be quite similar in terms of signs and significance. However, due to the confounding scale parameter (which Table 3 shows to differ across samples), comparing the parameter estimates across samples would be inappropriate. The model using the pooled data in Table 3 enables a direct test of our hypothesis concerning the price parameters and scale differences in a single model. However, the WTP estimates presented in Table 4 are based on separate models estimated on the individual payment vehicle samples, and the patterns there support our choice.

Due to normalization, the relative error term variance is calculated as \(\sigma ^{2}=1/{\lambda ^{2}}\).

Abbreviations

- SP:

-

Stated preference

- DCE:

-

Discrete choice experiment

- WTP:

-

Willingness to pay

- RP:

-

Revealed preference

- RPL:

-

Random parameter logit

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

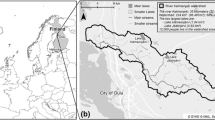

- SW:

-

Setiu Wetland

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Ajzen I, Brown TC, Rosenthal LH (1996) Information bias in contingent valuation: effects of personal relevance, quality of information, and motivational orientation. J Environ Econ Manag 30:43–57

Báez-Montenegro A, Bedate AM, Herrero LC, Sanz JÁ (2012) Inhabitants’ willingness to pay for cultural heritage: a case study in Valdivia, Chile, using contingent valuation. J Appl Econ 15:235–258

Bakhtiari F, Jacobsen JB, Jensen FS (2014) Willingness to travel to avoid recreation conflicts in Danish forests. Urban For Urban Green 13:662–671

Ben-Akiva M, Lerman SR (1985) Discrete choice analysis. Theory and application to travel demand. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Bierlaire M (2003) BIOGEME: a free package for the estimation of discrete choice models. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Swiss transportation research conference. Ascona, Switzerland

Blamey R (1998) Contingent valuation and the activation of environmental norms. Ecol Econ 24:47–72

Bradley M, Daly A (1994) Use of the logit scaling approach to test for rank-order and fatigue effects in stated preference data. Transportation (Amst) 21:167–184

Bridel A, Lontoh L (2014) Lessons Learned: Malaysia’s 2013 Fuel Subsidy Reform. International Institute for Sustainable Development

Broadbent CD (2012) Summary for policymakers. In: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed) Climate change 2013—the physical science basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–30

Cameron TA, DeShazo JR (2010) Differential attention to attributes in utility-theoretic choice models. J Choice Model 3:73–115

Campos P, Caparrós A, Oviedo JL (2007) Comparing payment-vehicle effects in contingent valuation studies for recreational use in two protected Spanish forests. J Leis Res 39:60–85

Carneiro DQ, Carvalho AR (2014) Payment vehicle as an instrument to elicit economic demand for conservation. Ocean Coast Manag 93:1–6

Carson RT, Groves T (2007) Incentive and informational properties of preference questions. Environ Resour Econ 37:181–210

Carson RT, Groves T, List JA (2014) Consequentiality: a theoretical and experimental exploration of a single binary choice. J Assoc Environ Resour Econ 1:171–207

Casiwan-Launio C, Shinbo T, Morooka Y (2011) Island villagers’ willingness to work or pay for sustainability of a marine fishery reserve: case of San Miguel Island, Philippines. Coast Manag 39:459–477

Champ PA, Flores NE, Brown TC, Chivers J (2002) Contingent valuation and incentives. Land Econ 78:591–604

Chen YK (2012) The progressivity of the Malaysian personal income tax system. Kaji Malaysia 30:27–43

ChoiceMetrics (2012) Ngene 1.1.1 user manual & reference guide, Version: 16/02/2012. In: Ngene Man. https://www.choice-metrics.com. Accessed 18 Nov 2013

Demeke M, Pangrazio G, Maetz M (2009) Country responses to the food security crisis: nature and preliminary implications of the policies pursued. Int Organ 19:112

Do TN, Bennett J (2009) Estimating wetland biodiversity values: a choice modelling application in Vietnam’s Mekong River Delta. Environ Dev Econ 14:163

DOSM (2010) Population and housing census of Malaysia. In: Dep. Stat. Malaysia. https://www.statistics.gov.my. Accessed 12 Jan 2013

EPU (2013) The Malaysian Economy in Figures. Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Deparment

Flores NE, Strong A (2007) Cost credibility and the stated preference analysis of public goods. Resour Energy Econ 29:195–205

Gibson JM, Rigby D, Polya DA, Russell N (2016) Discrete choice experiments in developing countries: willingness to pay versus willingness to work. Environ Resour Econ 65:697–721

Gordon R, Li W (2009) Tax structures in developing countries: many puzzles and a possible explanation. J Public Econ 93:855–866

Hensher D, Shore N, Train K (2005) Households’ willingness to pay for water service attributes. Environ Resour Econ 32:509–531

Hung LT, Loomis JB, Thinh VT (2007) Comparing money and labour payment in contingent valuation: the case of forest fire prevention in Vietnamese context. J Int Dev 19:173–185

Ivehammar P (2009) The payment vehicle used in CV studies of environmental goods does matter. J Agric Resour Econ 34:450–463

Jacobsen JB, Lundhede TH, Thorsen BJ (2012) Valuation of wildlife populations above survival. Biodivers Conserv 21:543–563

Kaffashi S, Shamsudin MN, Radam A et al (2013) We are willing to pay to support wetland conservation: local users’ perspective. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol 20:325–335

Kahneman D, Knetsch JL (1992) Valuing public goods: the purchase of moral satisfaction. J Environ Econ Manag 22:57–70

Kamil NF (2008) Ecosystem functions and services and sustainable livelihood of the wetlands communities. Int J Environ Cult Econ Soc Sustain 4:85–92

Khamis MR, Md Salleh A, Nawi AS (2011) Compliance behavior of business Zakat payment in Malaysia: a theoretical economic exposition. In: 8th international conference on islamic economies and finance: sustainable growth and inclusive economic development from an Islamic perspective, pp 1–17

LaRiviere J, Czajkowski M, Hanley N et al (2014) The value of familiarity: effects of knowledge and objective signals on willingness to pay for a public good. J Environ Econ Manag 68:376–389

Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Carson RT (2010) Discrete choice experiments are not conjoint analysis. J Choice Model 3:57–72

Lundhede TH, Olsen SB, Jacobsen JB, Thorsen BJ (2009) Handling respondent uncertainty in choice experiments: evaluating recoding approaches against explicit modelling of uncertainty. J Choice Model 2:118–147

Lusk JL, McLaughlin L, Jaeger SR (2007) Strategy and response to purchase intention questions. Mark Lett 18:31–44

Lyssenko N, Martínez-Espiñeira R (2012) Respondent uncertainty in contingent valuation: the case of whale conservation in Newfoundland and Labrador. Appl Econ 44:1911–1930

McFadden D (1974) Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka P (ed) Frontiers in econometrics. Academic Press, New York, pp 105–142

Meyerhoff J, Liebe U (2009) Status quo effect in choice experiments: empirical evidence on attitudes and choice task complexity. Land Econ 85:515–528

Milon JW (1989) Contingent valuation experiments for strategic behavior. J Environ Econ Manag 17:293–308

Mørkbak MR, Olsen SB, Campbell D (2014) Behavioral implications of providing real incentives in stated choice experiments. J Econ Psychol 45:102–116

Morrison MD, Blamey RK, Bennett JW (2000) Minimising payment vehicle bias in contingent valuation studies. Environ Resour Econ 16:407–422

Ndunda EN, Mungatana ED (2013) Evaluating the welfare effects of improved wastewater treatment using a discrete choice experiment. J Environ Manag 123:49–57

Newtown G (2012) Buffer zones for aquatic biodiversity conservation. Australas Plant Conserv 21:18–22

Othman J, Bennett J, Blamey R (2004) Environmental values and resource management options: a choice modelling experience in Malaysia. Environ Dev Econ 9:803–824

Revelt D, Train K (1998) Mixed logit with repeated choices: households’ choices of appliance efficiency level. Rev Econ Stat 80:647–657

Scarpa R, Thiene M (2005) Destination choice models for rock climbing in the Northeastern Alps: a latent-class approach based on intensity of a latent-class approach preferences. Land Econ 81:426–444

Schiappacasse I, Vásquez F, Nahuelhual L, Echeverría C (2013) Labor as a welfare measure in contingent valuation: the value of a forest restoration project. Agric Econ 40:69–84

Solaymani S, Kari F (2014) Impacts of energy subsidy reform on the Malaysian economy and transportation sector. Energy Policy 70:115–125

Stithou M, Scarpa R (2012) Collective versus voluntary payment in contingent valuation for the conservation of marine biodiversity: an exploratory study from Zakynthos, Greece. Ocean Coast Manag 56:1–9

Swait J, Louviere J (1993) The role of the scale parameter in the estimation and comparison of multinomial logit models. J Mark Res 30:305

Taylor LO (1998) Incentive compatible referenda and the valuation of environmental goods. Agric Resour Econ Rev 27:132–139

Train K (1998) Recreation demand models with taste differences over people. Land Econ 74:230–239

Train K (2003) Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Vossler CA, Watson SB (2013) Understanding the consequences of consequentiality: testing the validity of stated preferences in the field. J Econ Behav Organ 86:137–147

Vossler CA, Doyon M, Rondeau D (2012) Truth in consequentiality: theory and field evidence on discrete choice experiments. Am Econ J Microecon 4:145–171

Whittington D, Pagiola S (2012) Using contingent valuation in the design of payments for environmental services mechanisms: a review and assessment. World Bank Res Obs 27:261–287

Wiser RH (2007) Using contingent valuation to explore willingness to pay for renewable energy: a comparison of collective and voluntary payment vehicles. Ecol Econ 62:419–432

Yacob MR, Radam A, Samdin Z (2011) Willingness to pay for domestic water service improvements in Selangor, Malaysia: a choice modeling approach. Int Bus Manag 2:30–39

Yang W, Chang J, Xu B et al (2008) Ecosystem service value assessment for constructed wetlands: a case study in Hangzhou, China. Ecol Econ 68:116–125

Zawojska E (2016) When do respondents state their preferences truthfully? Zurich, Switzerland, 24th June 2016

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the help of reviewers and the editor in improving the manuscript. We acknowledge the financial assistance from of Universiti Putra Malaysia and Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia. A support from the research group of Responsible Rural Tourism Network and Ministry of Higher Education’s (Malaysia) Long Term Research Grant Scheme (LRGS) Programme [Reference No: JPT.S (BPKI) 2000/09/01/015Jld.4 (67)]. B. J. Thorsen further acknowledges the support from the Danish National Research Foundation (Centre of Excellence Grant DNRF 96).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The actual descriptions of the payment vehicles presented to respondents (translated from the Malay language)

PaymentVehicle | Description of conservation cost |

|---|---|

Subsidy | (1) A policy to implement a conservation program for this wetland will require funding for the costs of the program. The government is planning to do so by lowering the current subsidies for groceries such as flour, cooking oil, liquid natural gas, and fuel and to use the freed funds to implement the conservation program. Thus, the different alternative policies will incur a necessary yearly cost to your household, as you will have to pay more for these everyday goods that will now be less subsidized |

(2) The possible amounts that this additional expense may cost your household are stated below: | |

RM 0/year, RM 5/year, RM 10/year, RM 30/year, RM 90/year, RM 210/year, RM 400/year | |

(3) Here, we’d like to ask your opinion about some of these attributes for the conservation of the SW. If adopted, it would be financed through sources that will eventually reduce your household’s income | |

(4) We will ask you to compare two alternative management policies along with the current state and to tell us which one you would support in practice | |

(5) Please also consider your choices under the precondition that if implemented, the payments will be made through a reduction in subsidies for fuel, groceries, etc. enjoyed by you and other households. In other words, these goods will become more expensive to buy, so you would have to spend the additional specified amount per year on these goods | |

(6) The results of this survey are advisory. In other words, they will be used to inform policymakers on the opinions and preferences of Malaysians to help them see how important conservation of the SW is and how it can be improved | |

(7) Please think carefully about how much you can really afford through subsidy reductions. You can also choose not to pay if you think that you can’t afford it and you prefer to spend your income on other things | |

Donation | (1) A policy to implement a conservation program for this wetland will require funding for the costs of the program. The government is planning to do so by raising the funds through voluntary donations and using the freed funds to implement the conservation program. Thus, the different alternative policies will incur a necessary yearly cost to your household, as you will have to give some of your income to that fund |

(2) Similar to subsidy version | |

(3) Similar to subsidy version | |

(4) Similar to subsidy version | |

(5) Please also consider your choices under the precondition that if implemented, the payments will be made through the fund from voluntary donations by your household (and other households) | |

(6) Similar to subsidy version | |

(7) Please think carefully about how much you can really afford if you need to provide a voluntary donation. You can also choose not to pay if you think that you can’t afford it and you prefer to spend your income on other things | |

Income tax | (1) A policy to implement a conservation program for this wetland will require funding for the costs of the program. The government is planning to do so by increasing/charging an income tax and using the freed funds to implement the conservation program. Thus, the different alternative policies will incur a necessary yearly cost to your household, as you will have to pay more in income taxes |

(2) Similar to subsidy version | |

(3) Similar to subsidy version | |

(4) Similar to subsidy version | |

(5) Please also consider your choices under the precondition that if implemented, the payments will be made by increasing or levying income taxes on your household (and other households) | |

(6) Similar to subsidy version | |

(7) Please think carefully about how much you can really afford if you experience an increase in your income taxes. You can also choose not to pay if you think that you can’t afford it and you prefer to spend your income on other things |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, S., Olsen, S.B. & Thorsen, B.J. Appropriate Payment Vehicles in Stated Preference Studies in Developing Economies. Environ Resource Econ 71, 1053–1075 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-017-0196-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-017-0196-6